Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents a significant cause of morbidity and mortality globally. While sex workers (SWs) may face elevated HCV risks through both drug/sexual pathways, incidence data among SWs are severely lacking. We characterized HCV incidence and predictors of HCV seroconversion among women SWs in Vancouver, BC.

Methods

Questionnaire and serological data were drawn from a community-based cohort of women SWs (2010–2014). Kaplan-Meier methods and Cox regression were used to model HCV incidence and predictors of time to HCV seroconversion.

Results

Among 759 SWs, HCV prevalence was 42.7%. Among 292 baseline-seronegative SWs, HCV incidence density was 3.84/100 person-years(PY), with higher rates among women using injection drugs (23.30/100 PY) and non-injection crack (6.27/100 PY), and those living with HIV (13.27/100 PY) or acute STIs (5.10/100 PY). In Cox analyses adjusted for injection drug use, age (HR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.86–1.01), acute STI infection (HR: 2.49, 95%CI: 1.02–6.06), and non-injection crack use (HR: 2.71, 95%CI: 1.18–6.25) predicted time to HCV seroconversion.

Discussion

While HCV incidence was highest among women who inject drugs, STIs and non-injection stimulant use appear to be pathways to HCV infections, suggesting potential dual sexual/drug transmission. Integrated HCV services within sexual health and HIV/STI programs are recommended.

Keywords: hepatitis C, HIV, sexually transmitted infections, sex work

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents a significant and rising global public health issue, with 185 million people estimated to be living with HCV1,2. Most persons living with HCV are chronically infected, which poses a high risk of developing liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, and chronic liver disease2. In May 2016, the first-ever global hepatitis targets were adopted by the World Health Assembly, galvanizing attention for this previously under-recognized and relatively neglected health priority. These include reducing new viral hepatitis infections by 90% and reducing deaths due to viral hepatitis by 65% by 2030, supporting increasing calls for scaling-up access to HCV prevention, treatment and care3.

HCV is known to disproportionately affect marginalized and underserved populations, primarily people who inject drugs (PWID)4–6, and to a lesser extent, men who have sex with men (MSM)5,7. Although research on HCV among people who use non-injection drugs has recently increased, little remains known regarding HCV incidence among other key populations, particularly sex workers, who face potentially elevated risks due to dual drug and sexual transmission pathways. While little is known about HCV among sex workers, sex workers face a greatly elevated burden of HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and other sexual and drug-related harms. These harms have been primarily attributed to structural factors, including violence, unsafe working conditions, stigma, and criminalization, which undermine the negotiation of sexual and drug risk mitigation8,9 as well as access to health and harm reduction services10,11.

Among a small body of research on HCV among sex workers from non-endemic settings such as Estonia12, Argentina13, and South Korea14, HCV prevalence has been found to be consistently higher than the general population, ranging from 1.4% among sex workers in South Korea to 7.9% in Estonia. Although few studies have assessed predictors of HCV incidence or prevalence among sex workers, previous work suggests that sex workers who are street-involved, criminalized, use drugs, and engage in syringe-sharing are particularly vulnerable to HCV15,16. Amidst global calls for HCV treatment scale-up for key populations and the rising availability of new and highly effective direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatments for HCV, addressing the gap in epidemiological data regarding the incidence and prevalence of HCV among sex workers remains of paramount importance.

In Metropolitan Vancouver, British Columbia (BC), women sex workers face a disproportionate burden of HIV (with an estimated prevalence of 12%)8,17, elevated sexual and drug-related harms18,19, and structural barriers to HIV and harm reduction services8,10,11. Due to advances in HCV treatments, current efforts to scale-up HCV treatment are currently being explored in BC, particularly for key populations facing intersecting harms related to substance use disorders, HIV and HCV. Given evidence suggesting the potential for dual sexual and drug risk pathways for HCV acquisition, particularly within the context of sex with multiple partners, and the current dearth of HCV incidence among sex workers, this study aimed to characterize incidence and predictors of HCV infection among sex workers in Metropolitan Vancouver, BC.

METHODS

Data collection

Data were drawn from An Evaluation of Sex Workers’ Health Access (AESHA), a prospective cohort of over 800 women sex workers recruited through street, indoor and online outreach across Metropolitan Vancouver from January 2010 – August 2014. AESHA is based on collaborations with sex work agencies which have existed since 2005 and is monitored by a Community Advisory Board of >15 organizations. The study was approved by the Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

As previously17, eligibility criteria included self-identifying as a woman (transgender male-to-female inclusive), ≥14 years old, exchanged sex for money within the last month and provided informed consent. Sample size was calculated to detect associations between structural determinants of primary interest (e.g., work environments, policing) and HIV/STI incidence. Time-location sampling was used to recruit participants through weekly outreach to street, indoor and online venues across Metropolitan Vancouver, which were identified through community mapping and regularly updated. Between 10–15% of individuals screened are deemed ineligible for the cohort. The primary reason for ineligibility is not being actively engaged in sex work at baseline (e.g., did not work within the last 30 days); other reasons account for 5% of those screened as ineligible, and include living outside the Metropolitan Vancouver area or being unable to provide informed consent. Following an open cohort design, participants continue to be actively recruited throughout the life of the cohort through extensive ongoing outreach to street, indoor and online venues. Annual retention of participants under active follow-up is >90%, and primary reasons for attrition include mortality and migration outside Metropolitan Vancouver. Extensive efforts are made to continue to follow women who move outside Metropolitan Vancouver during the study, including mobile outreach/interview teams and phone interviews, to support high retention rates.

At baseline and semi-annually, participants completed interviewer-administered questionnaires in English, Cantonese, or Mandarin by trained interviewers (including both experiential (sex workers) and non-experiential staff), alongside pre- and post-test counseling and voluntary HIV, STI and HCV testing. The questionnaire collected detailed information on socio-demographics, sex work patterns, sexual health and substance use, occupational and lifetime violence, health and social services access, and structural features of occupational and residential environments. Participants completed study visits at one of two storefront offices in Metropolitan Vancouver or at their work/home location. All participants received $40CAD at each visit for their time, expertise and travel.

Voluntary HIV, STI and HCV testing and pre/post-test counseling was performed by a project nurse. As per provincial guidelines, HIV testing was performed using ELISA, with reactive tests followed by Western Blot and individual RNA Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT) testing where necessary. Urine samples were collected to test for acute STIs including gonorrhea and chlamydia using NAAT. Blood was drawn for syphilis, HSV-2 antibody, and HCV-antibody testing. Onsite treatment was provided by our project nurse for symptomatic STIs, and free STI and Papanicolaou testing were also offered, regardless of study enrolment. Nurses offered referral and active connections to care to HIV and HCV-seropositive women not receiving care, as well as education and referrals to other needed health and social services.

Data analysis

Analyses were restricted to women who were HCV-antibody negative at baseline and who had at least one follow-up visit. Independent variables of interest were identified a priori and included socio-demographic characteristics such as age and Indigenous ancestry. Time-updated variables used the last 6 months as a reference point and included HIV and acute STI infections (defined as a new diagnosis of chlamydia, gonorrhea or syphilis), assessed based on serological and urine test results; sexual and drug-related risks, including condom negotiation and use (e.g., inconsistent condom use with clients) and drug use (e.g., non-injection drug use, injection drug use, non-injection crack use); and interactions with health and social services, assessed by asking if participants had experienced any barriers to accessing healthcare or harm reduction services. Women previously diagnosed as HCV-seropositive were also asked several questions regarding their access and uptake of HCV care, including whether they had received regular blood tests for HCV, had seen an HCV specialist, had been offered HCV treatment and had been receiving HCV treatment. Other time-updated variables included structural exposures, including participants’ primary place of soliciting clients (coded as outdoor/public vs. indoor/independent), homelessness, client-perpetrated physical/sexual violence, and experiences related to policing and criminalization, including incarceration, police harassment or arrest.

Kaplan Meier Analyses

Kaplan Meier methods were used to estimate cumulative HCV incidence. The date of HCV-seroconversion was estimated as the midpoint between the last negative and the first positive antibody test result. Participants who remained persistently HCV-seronegative were right censored at the time of their most recent available HCV antibody test result. Time-zero for all prospective analyses was the date of recruitment into the respective cohorts. Incidence rates were estimated among the full sample and stratified by risk factors including recent injection drug use, non-injection crack use, and co-infection with HIV or an STI at baseline.

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression

Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we calculated the unadjusted and adjusted relative hazards of HCV seroconversion. Time-fixed variables included sociodemographics such as age, duration of sex work, and Indigenous ancestry; all other variables (e.g., drug use, sexual behaviours, structural exposures) were treated as time-updated covariates with occurrences in the prior 6 months, based on semi-annual follow-up data. For the multivariable model, a fixed model was built that adjusted for all variables described above that were statistically associated with HCV seroconversion in unadjusted analyses. Given the established role of injection drug use in HCV transmission, multivariable analyses adjusted for daily, less than daily, or no injection drug use. A complete case analysis was performed, where cases with missing observations were excluded from the multivariable model. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC); the threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

HCV Burden and Participant Characteristics

At baseline, of 759 sex workers, 324 (42.7%) were HCV-seropositive. The median age of participants was 34 (inter-quartile range (IQR): 28–42) and one-third (34.7%) were of Indigenous 6 ancestry. A significantly higher prevalence of HCV was observed among older and Indigenous women as well as among women living with HIV or with acute STIs (Table 1). Women who use drugs faced a disproportionately higher HCV burden; in comparison to HCV-seronegative women, those who were HCV-seropositive at baseline were significantly more likely to inject drugs daily (41.9 vs. 6.2%) or less than daily (33.3% vs. 6.2%) and to use non-injection crack (86.1% vs. 39.5%) in the previous 6 months.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by baseline HCV prevalence among women sex workers in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014

| Variable | HCV-seropositive (N=324) n (%) | HCV-seronegative (N=435) n (%) | Total (N=759) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 36 (30–43) | 33 (26–41) | 34 (28–42) |

| Canadian-born | 299 (92.3%) | 234 (53.8%) | 533 (70.2%) |

| Indigenous | 160 (49.4%) | 103 (23.7%) | 263 (34.7%) |

| HIV-seropositive | 76 (23.5%) | 7 (1.6%) | 83 (10.9%) |

| STI-seropositive | 59 (18.2%) | 26 (6.0%) | 85 (11.2%) |

| Duration of sex work, years (median, IQR) | 16 (10–23) | 4 (1–10) | 9 (3–17) |

| Inconsistent condom use (clients)* | 73 (22.5%) | 66 (15.2%) | 139 (18.3%) |

| Anal sex with clients* | 62 (19.1%) | 40 (9.2%) | 102 (13.4%) |

| Any injection drug use* | 244 (75.3%) | 54 (12.4%) | 298 (39.3%) |

| Injection drug use* | |||

| Daily use | 136 (41.9%) | 27 (6.2%) | 163 (21.5%) |

| Less than daily use | 108 (33.3%) | 27 (6.2%) | 135 (17.8%) |

| No injection drug use | 80 (24.7%) | 381 (87.6%) | 461 (60.7%) |

| Any non-injection drug use* | 302 (93.2%) | 211 (48.5%) | 513 (67.6%) |

| Crack use | |||

| Non-injection crack use* | 279 (86.1%) | 172 (39.5%) | 451 (59.4%) |

| Injection crack use* | 33 (10.2%) | 7 (1.6%) | 40 (5.3%) |

| Primary place of solicitation* | |||

| Outdoor/public | 251 (77.5%) | 149 (34.3%) | 400 (52.7%) |

| Indoor/independent (ref) | 73 (22.5%) | 286 (65.8%) | 359 (47.3%) |

In last 6 months; NOTE: All data refer to n (%) of participants, unless otherwise specified.

HCV Incidence Density and Predictors of Time to HCV Seroconversion

At baseline, 292 women were HCV-antibody negative women and had at least one follow-up visit and were thus included in incidence analyses, contributing 1007 observations to the analysis and over 52.5 months of follow-up.

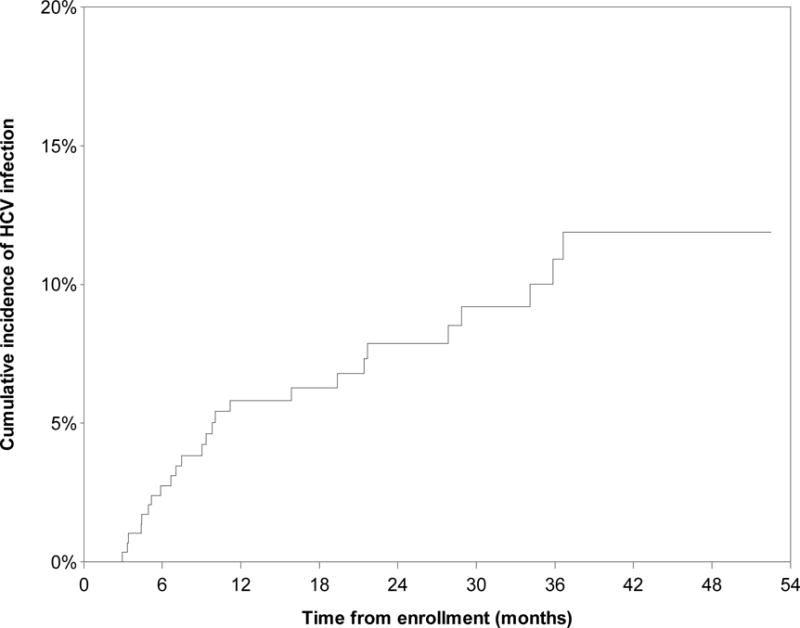

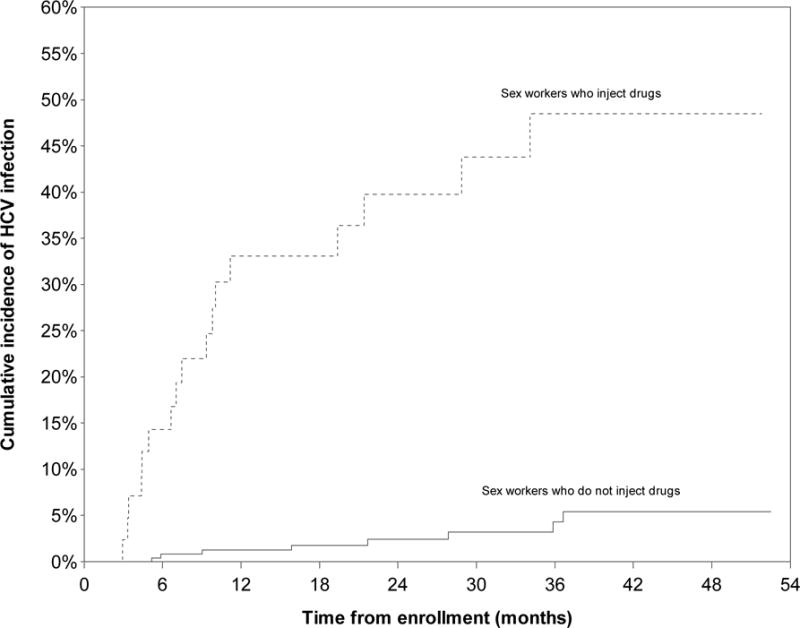

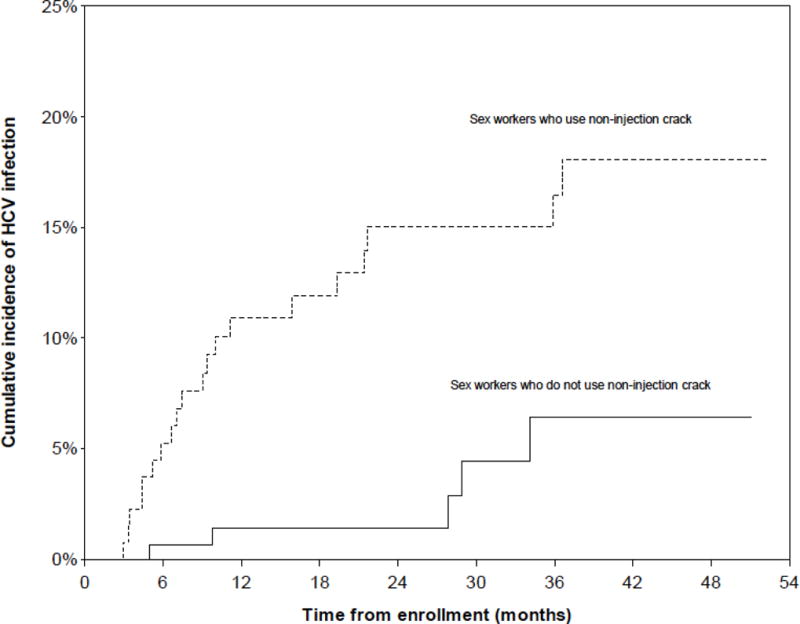

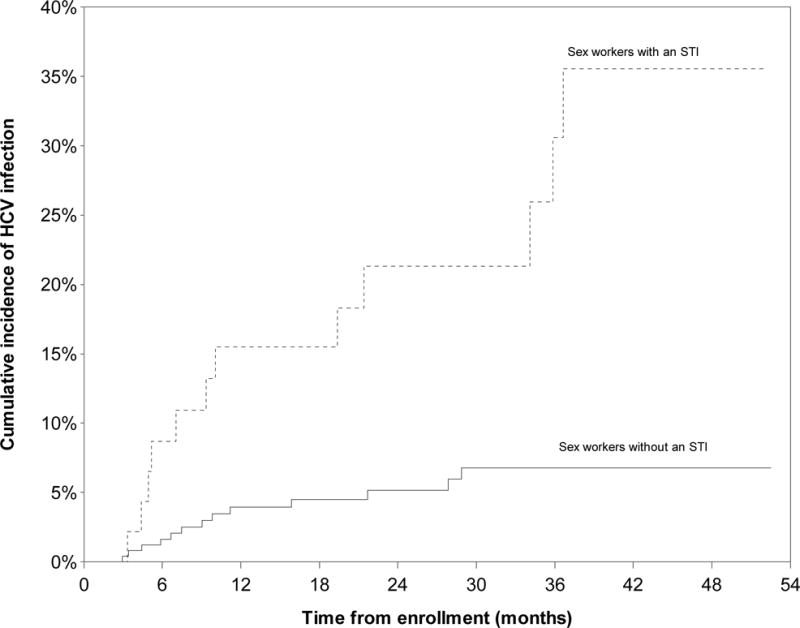

During the observation period, 25 new HCV seroconversions were identified, yielding an incidence density of 3.84/100 person-years (PY) (95% CI: 2.58–5.71). The Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence after 52.5 months of follow-up was 11.9% (Fig. 1). HCV incidence density was highest among women who used injection drugs, at 23.30/100 person-years (PY) (95% CI: 13.88–39.12) (Fig. 2) and was also significantly higher among women who used non-injection crack, at 6.27/100 PY (95% CI: 3.98–9.86)(Fig. 3). HCV incidence was also particularly high among women living with HIV (13.27/100 PY, 95% CI: 3.27–53.88) or who had an acute STI (5.10, 95% CI: 1.31–19.83) (Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier cumulative HCV incidence among HCV-antibody negative women sex workers (n=292) in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier cumulative HCV incidence among HCV-antibody negative women sex workers (n=292) in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014, stratified by injection drug use.

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier cumulative HCV incidence among HCV-antibody negative women sex workers (n=292) in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014, stratified by non-injection crack use.

Figure 4.

Kaplan Meier cumulative HCV incidence among HCV-antibody negative women sex workers (n=292) in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014, stratified by acute STI infections.

In unadjusted Cox regression models, the relative hazard (RH) of HCV seroconversion was higher among women who were younger (Hazard Ratio (HR): 0.91/year, 95% CI: 0.85–0.96), living with HIV (HR: 3.71, 95% CI: 0.91–15.10), had an acute STI (HR: 6.93, 95% CI: 2.84–16.92)(Table 2), and used non-injection crack (HR: 6.41, 95% CI: 2.43–16.90). The hazard of HCV seroconversion was substantially higher among sex workers who solicited clients in outdoor/public spaces (HR: 4.34, 95% CI: 1.80–10.49), experienced recent homelessness (HR: 4.14, 95% CI: 1.91–9.00), and faced structural risks related to policing and criminalization, including recent incarceration (HR: 4.02, 95% CI: 1.60–10.09).

Table 2.

Bivariate Cox analysis of time to incident HCV infection among sex workers in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014 (N=292)

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.91 | 0.85–0.96 |

| Indigenous | 2.07 | 0.95–4.52 |

| HIV-seropositive | 3.71 | 0.91–15.10 |

| STI-seropositive | 6.93 | 2.84–16.92 |

| Duration of sex work, years | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 |

| Inconsistent condom use (clients)* | 3.64 | 1.62–8.21 |

| Anal sex with clients* | 1.33 | 0.41–4.38 |

| Non-injection crack use* | 6.41 | 2.43–16.90 |

| Primarily solicits clients in outdoor/public spaces* | 4.34 | 1.80–10.49 |

| Homelessness* | 4.14 | 1.91–9.00 |

| Client physical/sexual violence* | 2.94 | 1.17–7.36 |

| Incarceration* | 4.02 | 1.60–10.09 |

| Police harassment* | 2.27 | 0.98–5.25 |

Time-updated measures using last 6 months as a reference

In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model, after adjustment for injection drug use, STI infection (HR: 2.49, 95%CI: 1.02–6.06), and non-injection crack use (HR: 2.71, 95%CI: 1.18–6.25) remained independent predictors of time to HCV seroconversion, and younger age was a marginally significant predictor (HR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.86–1.01; p=0.10).

DISCUSSION

In this 4.5-year study, after adjusting for injection drug use, younger age, having an STI, and using non-injection crack were independently associated with time to HCV seroconversion among women sex workers in Metropolitan Vancouver, Canada. HCV incidence was measured at 3.84/100 person-years (PY), which was highest among women who used injection drugs (23.30/100 PY), and was also measurably higher among women using non-injection crack (6.27/100 PY), as well as those living with HIV (13.27/100 PY). Although studies with PWID estimate HCV incidence to be between 20–40/100 PY6, declining incidence has been demonstrated among PWID in Vancouver and other settings characterized by the scale-up of effective, community-based harm reduction programs20,21. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine HCV incidence in a large cohort of sex workers, complementing the few prior studies that have examined HCV prevalence among sex workers elsewhere12,22,23. In comparison with an estimated HCV prevalence of 0.8%-2.8% in the general Canadian population24,25, 43% of sex workers were HCV-seropositive. The disproportionate HCV burden and relatively high incidence experienced by sex workers in this context highlight the urgent imperative to scale-up tailored and targeted HCV prevention, treatment, and care for marginalized women.

Whereas the sharing of drug paraphernalia and reuse of syringes are the most commonly acknowledged routes of HCV transmission, STI infections and non-injection stimulant use also appeared to be important pathways to HCV infections in this study, suggesting potential for dual sexual and drug– related transmission among sex workers. Alongside drug-related risks, studies have identified HIV and STI co-infections and sex with multiple partners as risk factors for HCV acquisition, particularly within high-income, low-prevalence settings2,26,27. In the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, after adjusting for drug use, women living with HIV were almost twice as likely to be HCV-seropositive28, an association primarily explained by sex with male PWID. Among MSM, Canadian and European studies have found SW involvement to be associated with HCV seropositivity; for example, in a Canadian study, HCV-seropositivity was found to be associated with a gonorrhea diagnosis among MSM with no history of injection drug use7.

In this study, non-injection crack use represented an important predictor of HCV seroconversion among sex workers; although a small proportion of women also reported using injected crack (5.3%), the small number of events of injection crack use during follow-up prevented its inclusion in Cox analysis. Prior work has demonstrated the potential for both drug-related and sexual HCV transmission. Shared non-injection drug use paraphernalia (e.g., mouthpieces, straws)29 and the use of inhaled and smoked stimulants (e.g., crack, cocaine) have been associated with elevated HCV prevalence among substance-using and low-income women27, women at risk of or living with HIV in the U.S.30, and men and women who use drugs31. Additionally, previous work has shown that elevated sexual and drug-related risks are often experienced within the context of overlapping risks related to sex work and crack use9,32; for example, associations have been reported between HCV infection and non-injection (i.e., inhaled, smoked) crack use, as well as sex work while using crack32. In Vancouver, we have previously shown how stimulant use (e.g., crack, crystal meth) within the context of sex work relates to broader patterns of poorer health outcomes and enhanced structural vulnerabilities18,19, including enhanced risk of violence, poor housing, police harassment, and reduced health access.18 Importantly, previous work suggests that gendered dynamics may be linked to enhanced HCV-related vulnerability among stimulant-using women, for whom sexual and drug-related risks are frequently experienced within the context of intimate and paid relationships with substance-using male partners9,19,28,32. Although this body of evidence supports the notion that the associations we documented between STI infections and non-injection crack use may be attributable to overlapping sexual and non-injection related drug transmission of HCV, it is also possible that these variables to some extent may represent markers of a higher-risk population of sex workers, rather than actual transmission pathways. Future studies with sex workers and other populations that may be exposed to dual sexual and drug-related risks are recommended to further explore these transmission pathways across diverse settings.

Younger sex workers in this cohort also faced a trend towards higher HCV incidence, pointing to gaps in harm reduction and HCV prevention efforts for marginalized young women. In high-income contexts such as the U.S. and Australia, HCV transmission is disproportionately concentrated among young adults2, and North American studies indicate that street-involved youth who use drugs are highly vulnerable to HCV33,34. Importantly, our findings build on a prior study among drug-using youth in Vancouver, which found that sex work involvement was associated with HCV seroconversion for youth15. These findings can be contextualized by previous research with involving marginalized populations, including sex workers and PWUD, which shows that youth often face greater risk of blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections due to the enhanced challenges faced negotiating condoms use and drug-related harms (frequently with older partners), particularly within the context of recent sex work or drug use initiation17,33.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

In this study, while HCV incidence was highest among women who inject drugs, sex workers with acute STIs and who use non-injection crack also faced substantially increased risk of HCV acquisition, highlighting the need to integrate HCV services with sexual health and HIV/STI and substance use prevention and treatment programs in this setting. The concerning trend of higher HCV incidence among younger women underscores the need for youth and sex worker-friendly HCV programming. These recommendations are supported by the recently adopted Global Health Sector Strategies for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections (2016–2021), which include greater integration across HIV, STI, and viral hepatitis prevention, treatment and care, and a purposeful focus on key populations, including sex workers. The pervasive barriers sex workers face to HIV, sexual health and harm reduction services have been primarily linked to the enforcement of criminalized legal approaches to sex work. For example, displacement due to policing and the resulting lack of safe working and living environments for sex workers often undermine access to HIV, health, and harm reduction services18. As such, structural interventions, including the decriminalization of sex work, remain critical to ensuring access to HIV, HCV and harm reduction programs.

In Vancouver, we recently demonstrated the severe gaps in HCV testing and treatment faced by sex workers, with fewer than half of HCV-positive women being connected to care and almost none having received treatment35. Despite high HCV prevalence and incidence among sex workers, most HCV-related services target PWID, with a lack of sex worker-tailored or women-centred models of care. While HCV treatment uptake has been historically low for substance-using populations, new, highly effective and tolerable HCV treatments represent an opportunity to scale-up voluntary and respectful treatment access. Importantly, recent studies have demonstrated that marginalized and substance-using populations can achieve rates of virological response comparable to the general population4, with modeling also suggesting that expanding harm reduction and HCV treatment access to persons at increased risk for transmission has the potential to reduce HCV incidence and prevalence in a cost-effective manner4.

Conclusions

In this study, while HCV incidence was highest among sex workers who inject drugs and women living with HIV, STIs and non-injection stimulant crack use appear to be pathways to HCV infections, suggesting potential dual sexual and drug-related transmission of HCV. Altogether, findings from this study highlight the urgent need for integration of HCV services with sexual health and HIV/STI addiction and harm reduction programs for marginalized women. In light of very high HCV prevalence and incidence rates among sex workers and the recent availability of highly-effective and tolerable HCV treatment regimens, targeted, community-based efforts to offer voluntary HCV prevention (including prevention of re-infection), testing, treatment and care to sex workers should be a critical public health and human rights priority.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox analysis of time to incident HCV infection among sex workers in Metropolitan Vancouver, 2010–2014 (N=292)

| Variable | Adjusted Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.94 | 0.86–1.01 |

| STI-seropositive | 2.49 | 1.02–6.06 |

| Non-injection crack use* | 2.71 | 1.18–6.25 |

Time-updated measures using last 6 months as a reference

NOTE: Results are adjusted for daily, less than daily, or no injection drug use in the last 6 months. Other variables which were considered, but not retained, in the final model included client-perpetrated physical/sexual violence and incarceration in the last 6 months.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those who contributed their time and expertise to this project, particularly participants, AESHA community advisory board members and partner agencies. We wish to acknowledge Chrissy Taylor, Jill Chettiar, Jennifer Morris, Tina Ok, Avery Alder, Emily Groundwater, Jane Li, Sylvia Machat, Lauren Martin McCraw, Minshu Mo, Brittany Udall, Rachel Nicoletti, Emily Sarah Leake, Ray Croy, Natalie Blair, Anita Dhanoa, Emily Sollows, Nelly Gomez, Bridget Simpson, Jenn McDermid, Alka Murphy, Paul Nguyen, Sabina Dobrer, Kathleen Deering, Krista Butler, Layla Cameron and Peter Vann for their research and administrative support. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA028648), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HHP-98835), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Public Health Agency of Canada (HEB-330155), and MacAIDS. KS is partially supported by a Canada Research Chair in Global Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. SG is partially supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and the US National Institutes of Health. MES is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Bridge Fellow. JSGM has received limited unrestricted funding, paid to his institution, from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck and ViiV Healthcare. JSGM is supported with grants paid to his institution by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA036307).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C Fact Sheet. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World Journal of gastroenterology. 2007;13(17):2436. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Assembly. Draft global health sector strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grebely J, Robaeys G, Bruggmann P, et al. Recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):1028–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin NK, Vickerman P, Dore GJ, Hickman M. The hepatitis C virus epidemics in key populations (including people who inject drugs, prisoners and MSM): the use of direct-acting antivirals as treatment for prevention. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2015;10(5):374–80. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan H, Pouget ER, Des Jarlais DC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204(1):74–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong J, Moore D, Kanters S, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C and correlates of seropositivity among men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada: a cross-sectional survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2015 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duff P, Tyndall M, Buxton J, Zhang R, Kerr T, Shannon K. Sex-for-Crack exchanges: associations with risky sexual and drug use niches in an urban Canadian city. Harm reduction journal. 2013;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg SMMJ, Duff P, Nguyen P, Dobrer S, Guillemi S, Shannon K. Structural Barriers to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV Seropositive Female Sex Workers: Findings of a Longitudinal Study in Vancouver, Canada. AIDS and Behavior. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1102-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Socias MESK, Horton M, Nguyen P, Lyons T, Martin R, Mannoe M, Deering KN. Recent incarceration correlated with reduced access to HIV prevention in a longitudinal study of sex workers who inject drugs in a Canadian urban centre. 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Vancouver, Canada. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uusküla A, Fischer K, Raudne R, et al. A study on HIV and hepatitis C virus among commercial sex workers in Tallinn. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008;84(3):189–91. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bautista CT, Pando MA, Reynaga E, et al. Sexual practices, drug use behaviors, and prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HTLV-1/2 in immigrant and non-immigrant female sex workers in Argentina. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2009;11(2):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kweon S-S, Shin M-H, Song H-J, Jeon D-Y, Choi J-S. Seroprevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among female commercial sex workers in South Korea who are not intravenous drug users. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2006;74(6):1117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shannon K, Kerr T, Marshall B, et al. Survival sex work involvement as a primary risk factor for hepatitis C virus acquisition in drug-using youths in a canadian setting. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2010;164(1):61–5. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor A, Hutchinson SJ, Gilchrist G, Cameron S, Carr S, Goldberg DJ. Prevalence and determinants of hepatitis C virus infection among female drug injecting sex workers in Glasgow. Harm reduction journal. 2008;5(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldenberg SM, Chettiar J, Simo A, et al. Early sex work initiation independently elevates odds of HIV infection and police arrest among adult sex workers in a Canadian setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(1):122–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a98ee6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shannon K, Strathdee S, Shoveller J, Zhang R, Montaner J, Tyndall M. Crystal methamphetamine use among female street-based sex workers: Moving beyond individual-focused interventions. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;113(1):76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon K, Bright V, Gibson K, Tyndall M. Sexual and drug-related vulnerabilities for HIV infection among women engaged in survival sex work in Vancouver, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2007;98(6):465–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03405440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grebely J, Lima VD, Marshall BD, et al. Declining incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting, 1996–2012. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e97726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iversen J, Wand H, Topp L, Kaldor J, Maher L. Reduction in HCV Incidence Among Injection Drug Users Attending Needle and Syringe Programs in Australia: A Linkage Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(8):1436–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. HIV, HBV, and HCV infections among drug-involved, inner-city, street sex workers in Miami, Florida. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(2):139–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LG, Corceal S. Unexpectedly High Injection Drug Use, HIV and Hepatitis C Prevalence Among Female Sex Workers in the Republic of Mauritius. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(2):574–84. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0278-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah HA, Heathcote J, Feld JJ. A Canadian screening program for hepatitis C: Is now the time? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2013;185(15):1325–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uhanova J, Tate RB, Tataryn DJ, Minuk GY. A population-based study of the epidemiology of hepatitis C in a North American population. Journal of hepatology. 2012;57(4):736–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tohme RA, Holmberg SD. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission? Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1497–505. doi: 10.1002/hep.23808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page-Shafer KA, Cahoon-Young B, Klausner JD, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in young, low-income women: the role of sexually transmitted infection as a potential cofactor for HCV infection. American journal of public health. 2002;92(4):670–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frederick T, Burian P, Terrault N, et al. Factors associated with prevalent hepatitis C infection among HIV-infected women with no reported history of injection drug use: the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) AIDS patient care and STDs. 2009;23(11):915–23. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tortu S, McMahon JM, Pouget ER, Hamid R. Sharing of noninjection drug-use implements as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Substance use & misuse. 2004;39(2):211–24. doi: 10.1081/ja-120028488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Operskalski EA, Mack WJ, Strickler HD, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis C viremia in a large cohort of HIV-infected and -uninfected women. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2008;41(4):255–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer B, Rehm J, Patra J, et al. Crack across Canada: Comparing crack users and crack non-users in a Canadian multi-city cohort of illicit opioid users. Addiction. 2006;101(12):1760–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shannon K, Rusch M, Morgan R, Oleson M, Kerr T, Tyndall MW. HIV and HCV prevalence and gender-specific risk profiles of crack cocaine smokers and dual users of injection drugs. Substance use & misuse. 2008;43(3–4):521–34. doi: 10.1080/10826080701772355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller CL, Kerr T, Fischer B, Zhang R, Wood E. Methamphetamine injection independently predicts hepatitis C infection among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(3):302–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;200(8):1216–26. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Socías ME, Shannon K, Montaner JS, et al. gaps in the hepatitis C continuum of care among sex workers in Vancouver, British Columbia: implications for voluntary hepatitis C virus testing, treatment and care. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;29(8):411–6. doi: 10.1155/2015/381870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]