Abstract

Objective

Asthma and corticosteroid use have been implicated as possible risk factors for schizophrenia. The retrospective cohort study herein aimed to investigate the association between asthma, corticosteroid use, and schizophrenia.

Method

Longitudinal data (2000 to 2007) from adults with asthma (n = 50,046) and without asthma (n = 50,046) were compared on measures of schizophrenia incidence using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Incidence of schizophrenia diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 295.XX) between 2000 and 2007 were compared between groups. Competing risk-adjusted Cox regression analyses were conducted, adjusting for sex, age, residence, socioeconomic status, corticosteroid use, outpatient and emergency room visit frequency, Charlson comorbidity index, and total length of hospital stays days for any disorder.

Results

Of the 75,069 subjects, 238 received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The mean (SD) follow-up interval for all subjects was 5.8 (2.3) years. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, asthma was associated with significantly greater hazard ratio for incident schizophrenia 1.40 (95% CI = 1.05, 1.87). Additional factors associated with greater incidence of schizophrenia were rural residence, lower economic status, and poor general health. Older age (i.e. ≥65 years) was negatively associated with schizophrenia incidence. Corticosteroid use was not associated with increased risk for schizophrenia.

Conclusions

Asthma was associated with increased risk for schizophrenia. The results herein suggest that a convergent disturbance in the immune-inflammatory system may contribute to the pathoetiology of asthma and schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe and chronic mental disorder that affects approximately one percent of the general population globally [1]. Schizophrenia is significantly associated with excess and premature mortality, higher rates of medical comorbidity, and deficits in cognitive and psychosocial functioning [2, 3]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the neurodegenerative and abnormal neurodevelopmental processes that subserve the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [4, 5]. One hypothesis posits that inflammatory disturbances may contribute to the etiology of schizophrenia.

Complex interactions between the immune system and the brain have been implicated in the pathoetiology of several psychiatric disorders [6]. For example, several epidemiological studies have reported on an increased risk for schizophrenia among those with autoimmune disorders and/or severe infections [7, 8]. The association between schizophrenia and autoimmune/infectious disorder suggests that there may be a convergent neurobiological substrate [9]. In addition, peripheral inflammation has been associated with greater permeability of the blood—brain barrier, facilitating the entry of immune molecules into the brain [10]. A disturbance in innate and adaptive immunity might contribute to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [11].

Studies have reported a strong positive correlation between asthma and other mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder and dementia [12–14]. However, only two previous reports (a single case-control design and separate cohort study) have documented an association between asthma and schizophrenia [15, 16]. Both of the foregoing studies reported on a positive correlation between schizophrenia and asthma. Similarly, other studies have reported that asthma patients more likely to develop psychosis experience than non-asthma patients [17–20]. In addition, some reports have reported on the potential impact of corticosteroids, which are commonly used by asthma patients, on the emergence of psychosis [19, 21]. However, no previous study, to our knowledge, has investigated the association between corticosteroid use and schizophrenia. Herein, we investigate the association between the incidence of schizophrenia among individuals with asthma, as well as the possible association between corticosteroid therapy and the incidence of schizophrenia, within a large, retrospective cohort study.

Materials and methods

Participants

A retrospective cohort study was assembled using data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) provided by the National Health Research Institute (NHRI). The NHIRD includes longitudinal data since its establishment in March 1997 from outpatient, ambulatory, hospital inpatient care, as well as dental services, covered by the National Health Insurance (NHI) program, which includes approximately 98% of Taiwan’s national population. In cooperation with the Bureau of NHI, the NHRI extracted a systematically sampled and nationally representative database of 1,000,000 people from the registry of all NHI enrollees to create the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID). There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, or health care utilization costs between the sample comprising the LHID and all enrollees of the NHI [22].

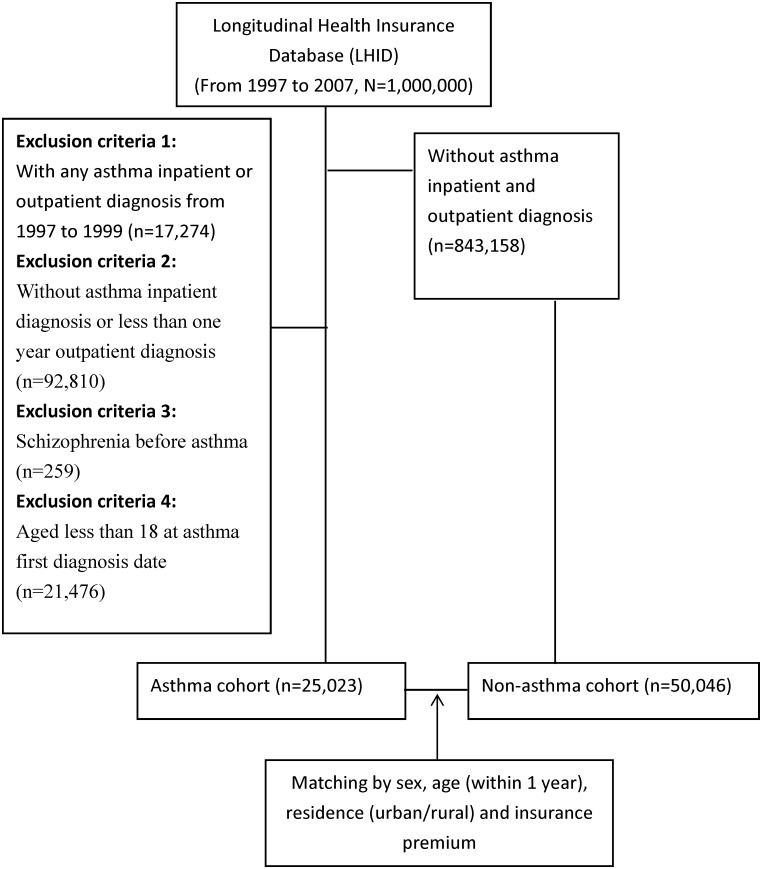

Incidence of schizophrenia diagnosis was measured and compared between individuals with and without asthma during the study period (i.e. 1997 to 2007). A diagnosis was operationalized as having a medical claim with the relevant diagnostic code on one occasion through inpatient services or on multiple occasions spread over at least one year through outpatient services; this operationalization is consistent with other research publications using the LHIRD [23]. Asthma was operationalized using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth revision (ICD-9) codes 493.XX. A diagnosis of schizophrenia was operationalized using the ICD-9 codes 295.XX. To assess the incidence of asthma within the study cohort, we excluded data from individuals with a diagnosis of asthma between 1997 and 1999 to make sure our asthma patients were new cases. We excluded data from individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia between 1997 and 1999 or with a diagnosis of schizophrenia prior to the diagnosis of asthma. Individuals without asthma (i.e. controls) were randomly sampled from the LHID and matched to individuals with asthma (i.e. cases) on measures of sex, age (+/- 1 year), residence (urban/rural) and insurance premium category. The method of data collection is illustrated in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Flowchart of the patient selection process.

Covariates considered in this analysis included age, sex, area of residence (urban/rural), economic status, corticosteroid use, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, Charlson comorbidity index and length of the total length of hospital stays for any disorder. In addition, the insurance premium class was classified into three categories and used to proxy economic status: lower income (i.e. requiring social welfare support, no stable salary); middle income (less than 20,000 New Taiwan Dollars [1 USD = 32.1 NTD in 2008] per month); and higher income (20,000 NTD or greater per month).

Corticosteroid use was operationalized and dichotomized as having (or not having) a prescription for corticosteroid for a minimum duration of one year; dose of corticosteroid use was quantified using the annual average cumulative defined daily dose (DDD), defined by the World Health Organization as the dispensed sum of DDDs within one year.

To assess the general physical health of participants during the study period, we used the number of outpatient visits and emergency room visits, total length of hospitalization(s), and Charlson comorbidity index. The foregoing variables were also considered as proxy severity of underlying inflammation. The Charlson comorbidity index comprises a summation of diseases [24].

The NHIRD consists of anonymized data released to the public for research purposes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital.

Statistical analysis

For cases, the index date was operationalized as the date of the incident diagnosis of asthma. The same index date was assigned to the respective matched controls. The outcome of analysis was an incident diagnosis of schizophrenia. The risks for schizophrenia were calculated using survival analyses, with the time function calculated as the number of years from the index date to December 31, 2008 (end of study period) or date of death/ migration (if applicable and earlier than December 31, 2008).

Death prior to incidence of schizophrenia was considered a competing risk event. The death date was retrieved from the national mortality database. The death-adjusted cumulative incidences of schizophrenia were calculated using the Fine and Gray method [25]. Competing risk-adjusted Cox regression models [25] were fitted to evaluate the associations between asthma and schizophrenia incidence, adjusting for covariates. We calculated the hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The model was tested first with all the sample cases included; we subsequently conducted subgroup analyses stratified by sex and age. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). To calculate cumulative incidence and Cox models in the competing risk analysis, we used the R package “cmprsk”[26].

Results

Characteristics of subjects

We identified 25,023 individuals with asthma and 50,046 matched controls in the LHID. Study cohort characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean (SD) follow-up interval for all subjects was 5.8 (2.3) years. Of the total 75,069 subjects, 238 were diagnosed with schizophrenia during the study period: 100 (0.40%) of subjects were in the asthma cohort and 138 (0.28%) in the non-asthma cohort. 2,918 (11.66%) individuals with asthma used corticosteroid during the study period, compared to 904 (1.81) individuals without asthma. The annual average cumulative DDD of asthma group 16.17±48.91 was greater than non-asthma group as 3.20±16.71. Individuals with asthma were also more likely than individuals without asthma to have poorer outcomes on measures of general health quality as assessed by the mean of outpatient visits, emergency room visits, Charlson comorbidity indices and total length of hospital stays.

Table 1. Characteristics of asthma cases and their matched a controls.

| Characteristic | Asthma | Non-asthma a | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 13383 | 53.48 | 26766 | 53.48 | >0.99 |

| Male | 11640 | 46.52 | 23280 | 46.52 | |

| Age group | |||||

| 18–44 | 8347 | 33.36 | 16692 | 33.35 | 0.951 |

| 45–64 | 8656 | 34.59 | 17363 | 34.69 | |

| ≥65 | 8020 | 32.05 | 15991 | 31.95 | |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 17876 | 71.44 | 35752 | 71.44 | >0.99 |

| Rural | 7147 | 28.56 | 14294 | 28.56 | |

| Insurance premium | |||||

| Fixed premium and dependent | 7163 | 28.63 | 14326 | 28.63 | >0.99 |

| Less than NTD b 20,000 | 5777 | 23.09 | 11554 | 23.09 | |

| NTD20,000 or more | 12083 | 48.29 | 24166 | 48.29 | |

| Corticosteroid (DDD c) | |||||

| 0–29 | 22105 | 88.34 | 49142 | 98.19 | <0.001 |

| 30–59 | 1447 | 5.78 | 463 | 0.93 | |

| ≥60 | 1471 | 5.88 | 441 | 0.88 | |

| Mean±SD | 16.17±48.91 | 3.20±16.71 | <0.001 | ||

| Schizophrenia | |||||

| No | 24923 | 99.6 | 49908 | 99.72 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 100 | 0.40 | 138 | 0.28 | |

| Outpatient visits d | |||||

| 0–10 | 314 | 1.25 | 4875 | 9.74 | <0.001 |

| 11–20 | 4928 | 19.69 | 17687 | 35.34 | |

| ≥21 | 19781 | 79.05 | 27484 | 54.92 | |

| Mean±SD | 27.76±22.56 | 16.73±17.12 | <0.001 | ||

| Emergency room visits d | |||||

| 0 | 22695 | 90.70 | 47358 | 94.63 | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 2050 | 8.19 | 2476 | 4.95 | |

| ≥3 | 278 | 1.11 | 212 | 0.42 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.15±0.67 | 0.07±0.41 | <0.001 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index e (Mean±SD) | 4.38±3.08 | 2.68±2.93 | <0.001 | ||

| Total length of hospital stays e (Mean±SD) | 37.94±131.29 | 18.39±86.42 | <0.001 | ||

a Matched by sex and age (±1 years old), residence, and insurance premium

b 1US $ = 32.1 NTD in 2008

c DDD: defined daily dose (mg)

d Past one year of index date.

e Past of index date.

Association between asthma and risk of schizophrenia

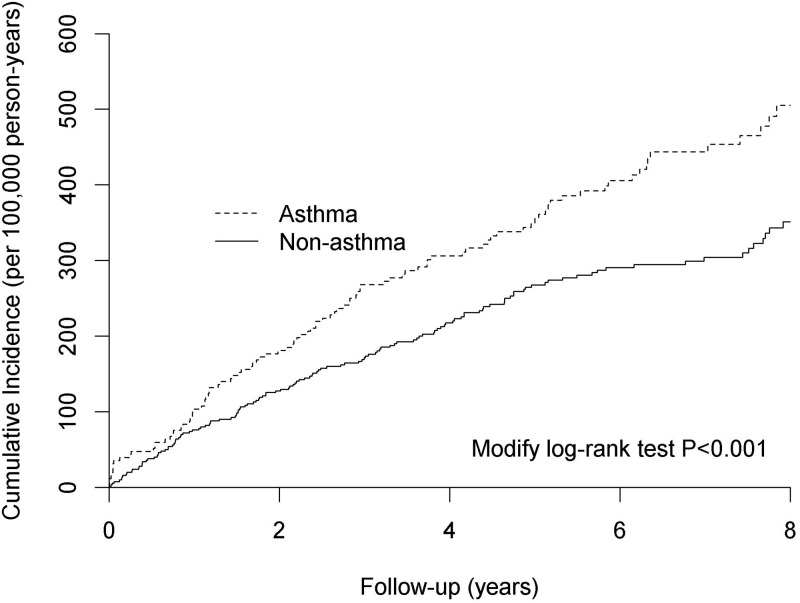

Analyses of associations of interest are presented in Table 2 and Fig 2. In the fully adjusted Cox regression model for competing risk analysis (i.e. sex, age group, residence, insurance premium, corticosteroid, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, Charlson comorbidity index, the total length of hospital stays and mortality), asthma was positively associated with schizophrenia. Additional factors associated with the incidence of schizophrenia were rural residence, lower economic status, and poor general health. Older age (i.e. ≥65 years) was negatively associated with schizophrenia incidence.

Table 2. Competing risk adjusted Cox regression analysis of schizophrenia incidence.

| Variable | Unadjusted hazard ratio | Adjusted a hazard ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Asthma | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.43 (1.10–1.84) | 0.007 | 1.40 (1.05–1.87) | 0.020 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.20 (0.93–1.55) | 0.167 | 1.17 (0.89–1.54) | 0.265 |

| Age group | ||||

| 18–44 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 45–64 | 1.06 (0.82–1.38) | 0.649 | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.434 |

| ≥65 | 0.73 (0.55–0.98) | 0.036 | 0.60 (0.39–0.89) | 0.002 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 1.31 (1.00–1.71) | 0.046 | 1.55 (1.17–2.04) | 0.002 |

| Insurance premium | ||||

| Fixed premium and dependent | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Less than NTD b 20,000 | 2.15 (1.66–2.80) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.04–1.97) | 0.030 |

| NTD20,000 or more | 0.46 (0.35–0.60) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.35–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroid (100 DDD c) | 1.16 (0.94–1.33) | 0.178 | 1.17 (0.95–1.39) | 0.250 |

| Outpatient visits d | ||||

| 0–10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 11–20 | 0.51 (0.32–1.08) | 0.105 | 0.59 (0.36–1.07) | 0.137 |

| ≥21 | 0.71 (0.47–1.08) | 0.111 | 0.83 (0.52–1.30) | 0.450 |

| Emergency room visits d | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–2 | 2.15 (1.42–3.25) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.38–3.24) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 2.49 (0.80–7.77) | 0.116 | 2.29 (0.72–7.27) | 0.159 |

| Charlson comorbidity index e | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.329 | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.139 |

| Total length of hospital stays e (100 days) | 1.09 (1.07–1.11) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | <0.001 |

a Competing risk adjusted Cox regression analysis controlling by sex, age, residence, insurance amount, corticosteroid, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, Charlson comorbidity index and total length of hospital stays.

b 1US $ = 32.1 NTD in 2008

c DDD: Defined daily dose (mg)

d Past one year of index date.

e Past of index date.

CI: Confidence interval.

Fig 2. Cumulative incidence of schizophrenia by study group (asthma versus non-asthma).

In secondary analyses within the asthma cohort, factors associated with incidence of schizophrenia included: older age (i.e. ≥65 years), rural residence, lower economic status and poor general health (Table 3). In stratified analyses, the association of interest was statistical significance in men and in the 18–64 year age group (Table 4).

Table 3. Competing risk adjusted Cox regression analysis of schizophrenia incidence among asthma patients.

| Variable | Unadjusted hazard ratio | Adjusted a hazard ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.03 (0.69–1.52) | 0.899 | 1.02 (0.68–1.52) | 0.941 |

| Age group | ||||

| 18–44 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 45–64 | 1.14 (0.76–1.71) | 0.513 | 0.90 (0.54–1.49) | 0.676 |

| ≥65 | 0.67 (0.42–1.05) | 0.083 | 0.49 (0.26–0.93) | 0.030 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 1.32 (0.87–1.99) | 0.190 | 1.54 (1.01–2.36) | 0.044 |

| Insurance amount | ||||

| Fixed premium and dependent | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Less than NTD b 20,000 | 2.23 (1.49–3.32) | <0.001 | 1.55 (0.95–2.52) | 0.077 |

| NTD20,000 or more | 0.48 (0.32–0.74) | 0.001 | 0.54 (0.32–0.92) | 0.023 |

| Corticosteroid (100 DDD c) | 1.13 (0.91–1.45) | 0.111 | 1.12 (0.90–1.56) | 0.356 |

| Outpatient visits d | ||||

| 0–10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 11–20 | 0.34 (0.10–1.15) | 0.082 | 0.41 (0.12–1.42) | 0.160 |

| ≥21 | 0.42 (0.13–1.32) | 0.138 | 0.56 (0.17–1.82) | 0.335 |

| Emergency room visits d | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–2 | 2.34 (1.35–4.05) | 0.002 | 2.27 (1.28–4.02) | 0.005 |

| ≥3 | 2.41 (0.59–9.78) | 0.219 | 2.24 (0.55–9.10) | 0.260 |

| Charlson comorbidity index e | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.509 | 0.96 (0.90–1.04) | 0.319 |

| Total length of hospital stays e (100 days) | 1.08 (1.05–1.10) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) | <0.001 |

a Competing risk adjusted Cox regression analysis controlling by sex, age, residence, insurance amount, corticosteroid, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, Charlson comorbidity index and total length of hospital stays.

b 1US $ = 32.1 NTD in 2008

c DDD: Defined daily dose (mg)

d Past one year of index date.

e Past of index date.

CI: Confidence interval.

Table 4. Association between asthma and schizophrenia incidence by sex and age group.

| Subgroup | Adjusted hazard ratio for schizophrenia a | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Total sample | 1.40 (1.05–1.87) | 0.020 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.59 (1.01–2.52) | 0.047 |

| Female | 1.30 (0.90–1.87) | 0.169 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–64 | 1.47 (1.03–2.12) | 0.044 |

| ≥65 | 1.25 (0.69–2.32) | 0.128 |

a Competing risk adjusted Cox regression analysis controlling by sex, age, residence, insurance amount, corticosteroid, outpatient visits, emergency room visits, Charlson comorbidity index and total length of hospital stays.

CI: Confidence interval.

Discussion

In our cohort study using the NHIRD, a diagnosis of asthma was significantly associated with a greater risk for schizophrenia (unadjusted hazard ratio = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.10 to 1.84). After adjusting for possibly confounding variables (i.e. sex, age, residence, economic status, corticosteroid use, general health quality), the adjusted hazard ratio was only modestly diminished to 1.40 (95% CI = 1.05–1.87). Corticosteroid use was not associated with greater risk for schizophrenia.

To our knowledge, this is one of few population-based cohort studies to report on an association between asthma and schizophrenia. In addition, to our knowledge, no previous study has reported on the moderation role of corticosteroid use on the foregoing association. Our results replicate findings from previous studies [15, 16] For example, Chen et al. [15] reported that, within a cross-sectional dataset, patients with schizophrenia had a 1.3-fold increased risk for concurrent asthma. A separate longitudinal study using [16] two nationwide population-based registers in Denmark reported that asthma is associated with increased risk for schizophrenia (HR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.31–1.90).

The association of corticosteroid use and psychosis has been reported in several previous studies [19, 21]. However, our findings did not find a statistically significant association between corticosteroid use and schizophrenia among asthma population. Bag et al. [21], showed a case report with steroid-induced psychosis in a 12-year-old boy and this may not be diagnosed as schizophrenia in clinical practice. Drozdowicz LB et al. [19], reported the review regrading psychiatric adverse effects of pediatric corticosteroid use. They found most of the evidence is still at the level of case reports, case series, and small trials. The psychosis experience, such as paranoid ideation, cannot be diagnosed as schizophrenia. Since the limitation of previous reports and most of them described the psychosis symptoms rather than schizophrenia, the association of corticosteroid use and schizophrenia is still unknown. We used the population-based cohort study to demonstrate that corticosteroid use is not linked to schizophrenia.

Immune-inflammatory processes may subserve the pathogenesis of asthma and schizophrenia [27–29] Emerging evidence suggests that infectious/autoimmune processes play an important role in the etiopathogenesis of subpopulations with schizophrenia [30, 31]. Among inflammatory peptides, cytokines are believed to contribute to the pathophysiology of many psychiatric illnesses, especially schizophrenia [32–36]. Available evidence indicates that abnormalities in the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in both central and peripheral compartments contribute to the abnormal neural structure and function reported in schizophrenia.

Limitations and strengths

This is one of few cohort studies using a nationally representative sample and longitudinal dataset to investigate the association between asthma and schizophrenia as well as the possible moderation role of corticosteroid use. The method of using the national database from NHIRD limits selection bias which is demonstrated from the similar prevalence of schizophrenia from the present study (0.27%) to that (0.2–0.3%) from community survey [37]. Furthermore, in our cohort study, we reduced the possibility of reverse casualty by using a longitudinal design in which the diagnosis of asthma predated the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

There are important limitations to our methodology that may limit inferences that may be made from our findings. The NHIRD did not contain data on possibly confounding variables such as smoking, dietary habits, family history and maternal condition. Another limitation is that although our data are based on physicians’ diagnoses, we cannot control for variability between clinicians in establishing a clinical diagnosis of asthma. Moreover, the severity of schizophrenia and asthma are unknown and could not be evaluated directly in the analysis herein. In epidemiological studies, the time of first symptom onset of asthma is most relevant. However, our study database did not contain information regarding first symptom onset of asthma.

Conclusions

The study suggests that the clinical care of patients with an asthma diagnosis necessitates monitoring for emerging psychopathology including, but not limited to schizophrenia. The future research vista is to identify convergent etipoathogenic mechanism subserving and or mediation the association between asthma and schizophrenia e.g immuno-inflammatory systems.

Data Availability

The data underlying this study is from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Interested researchers can obtain the data through formal application to the National Health Research Institute (NHRI), Taiwan. Additional information may be found at http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.html.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan (grant number: CMRPG6E0271). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Freedman R. Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(18):1738–49. 10.1056/NEJMra035458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson J, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;116(5):317–33. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kredentser MS, Martens PJ, Chochinov HM, Prior HJ. Cause and rate of death in people with schizophrenia across the lifespan: a population-based study in Manitoba, Canada. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(2):154–61. Epub 2014/03/08. 10.4088/JCP.13m08711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MR. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(5):434–49. Epub 2005/02/09. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pino O, Guilera G, Gomez-Benito J, Najas-Garcia A, Rufian S, Rojo E. Neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration: Review of theories of schizophrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2014;42(4):185–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najjar S, Pearlman DM, Alper K, Najjar A, Devinsky O. Neuroinflammation and psychiatric illness. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2013;10:43 10.1186/1742-2094-10-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SJ, Chao YL, Chen CY, Chang CM, Wu EC, Wu CS, et al. Prevalence of autoimmune diseases in in-patients with schizophrenia: nationwide population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(5):374–80. Epub 2012/03/24. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton WW, Byrne M, Ewald H, Mors O, Chen CY, Agerbo E, et al. Association of schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases: linkage of Danish national registers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):521–8. Epub 2006/03/04. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khandaker GM, Cousins L, Deakin J, Lennox BR, Yolken R, Jones PB. Inflammation and immunity in schizophrenia: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. The lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):258–70. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00122-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelhardt B, Sorokin L. The blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: function and dysfunction. Seminars in immunopathology. 2009;31(4):497–511. 10.1007/s00281-009-0177-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khandaker GM, Dantzer R. Is there a role for immune-to-brain communication in schizophrenia? Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(9):1559–73. 10.1007/s00213-015-3975-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen MH, Li CT, Tsai CF, Lin WC, Chang WH, Chen TJ, et al. Risk of Dementia Among Patients With Asthma: A Nationwide Longitudinal Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014. Epub 2014/07/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen MH, Su TP, Chen YS, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Chang WH, et al. Higher risk of developing major depression and bipolar disorder in later life among adolescents with asthma: a nationwide prospective study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;49:25–30. Epub 2013/11/28. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin TC, Lee CT, Lai TJ, Lee CT, Lee KY, Chen VC, et al. Association of asthma and bipolar disorder: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;168:30–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YH, Lee HC, Lin HC. Prevalence and risk of atopic disorders among schizophrenia patients: a nationwide population based study. Schizophr Res. 2009;108(1–3):191–6. Epub 2009/01/28. 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen MS, Benros ME, Agerbo E, Borglum AD, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia in patients with atopic disorders with particular emphasis on asthma: a Danish population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):58–62. Epub 2012/03/07. 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alpert O, Marwaha R, Huang H. Psychosis in children with systemic lupus erythematosus: the role of steroids as both treatment and cause. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(5):549.e1–2. Epub 2014/06/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown ES, Suppes T, Khan DA, Carmody TJ 3rd. Mood changes during prednisone bursts in outpatients with asthma. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):55–61. Epub 2002/01/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drozdowicz LB, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of pediatric corticosteroid use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(6):817–34. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Judd FK, Burrows GD, Norman TR. Psychosis after withdrawal of steroid therapy. Med J Aust. 1983;2(7):350–1. Epub 1983/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bag O, Erdogan I, Onder ZS, Altinoz S, Ozturk A. Steroid-induced psychosis in a child: treatment with risperidone. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(1):103 e5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institutes NHR. Introduction to the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), Taiwan 2014 [cited 2014]. http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.html.

- 23.Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Bettoncelli G, Cricelli C, Romeo F, Matera MG, et al. Cardiovascular disease in asthma and COPD: a population-based retrospective cross-sectional study. Respir Med. 2012;106(2):249–56. Epub 2011/08/23. 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods Inf Med. 1993;32(5):382–7. Epub 1993/11/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine JP G R. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cmprsk: Subdistribution Analysis of Competing Risks. R package version 2.2–7. The R Project for Statistical Computing.

- 27.Finkelman FD, Hogan SP, Hershey GKK, Rothenberg ME, Wills-Karp M. Importance of Cytokines in Murine Allergic Airway Disease and Human Asthma. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(4):1663–74. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maslan J, Mims JW. What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health care costs. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47(1):13–22. Epub 2013/11/30. 10.1016/j.otc.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saatian B, Rezaee F, Desando S, Emo J, Chapman T, Knowlden S, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cause barrier dysfunction in human airway epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1(2):e24333 Epub 2014/03/26. 10.4161/tisb.24333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganguli R, Rabin BS, Kelly RH, Lyte M, Ragu U. Clinical and laboratory evidence of autoimmunity in acute schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;496:676–85. Epub 1987/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribeiro-Santos A, Lucio Teixeira A, Salgado JV. Evidence for an immune role on cognition in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2014;12(3):273–80. Epub 2014/05/23. 10.2174/1570159X1203140511160832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garver DL, Tamas RL, Holcomb JA. Elevated interleukin-6 in the cerebrospinal fluid of a previously delineated schizophrenia subtype. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(8):1515–20. Epub 2003/06/12. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin A, Kenis G, Bignotti S, Tura GJ, De Jong R, Bosmans E, et al. The inflammatory response system in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: increased serum interleukin-6. Schizophr Res. 1998;32(1):9–15. Epub 1998/08/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potvin S, Stip E, Sepehry AA, Gendron A, Bah R, Kouassi E. Inflammatory cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: a systematic quantitative review. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(8):801–8. Epub 2007/11/17. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasayama D, Hattori K, Wakabayashi C, Teraishi T, Hori H, Ota M, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 levels in patients with schizophrenia and those with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(3):401–6. Epub 2013/01/08. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarlagadda A, Alfson E, Clayton AH. The blood brain barrier and the role of cytokines in neuropsychiatry. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(11):18–22. Epub 2010/01/06. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan defined by the Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79(2):136–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study is from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Interested researchers can obtain the data through formal application to the National Health Research Institute (NHRI), Taiwan. Additional information may be found at http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.html.