Abstract

Background

Universal screening for postpartum depression is recommended in many countries. Knowledge of whether the disclosure of depressive symptoms in the postpartum period differs across cultures could improve detection and provide new insights into the pathogenesis. Moreover, it is a necessary step to evaluate the universal use of screening instruments in research and clinical practice. In the current study we sought to assess whether the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the most widely used screening tool for postpartum depression, measures the same underlying construct across cultural groups in a large international dataset.

Method

Ordinal regression and measurement invariance were used to explore the association between culture, operationalized as education, ethnicity/race and continent, and endorsement of depressive symptoms using the EPDS on 8209 new mothers from Europe and the USA.

Results

Education, but not ethnicity/race, influenced the reporting of postpartum depression [difference between robust comparative fit indexes (Δ*CFI) < 0.01]. The structure of EPDS responses significantly differed between Europe and the USA (Δ*CFI > 0.01), but not between European countries (Δ*CFI < 0.01).

Conclusions

Investigators and clinicians should be aware of the potential differences in expression of phenotype of postpartum depression that women of different educational backgrounds may manifest. The increasing cultural heterogeneity of societies together with the tendency towards globalization requires a culturally sensitive approach to patients, research and policies, that takes into account, beyond rhetoric, the context of a person’s experiences and the context in which the research is conducted.

Keywords: Culture, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), education, postpartum depression, race

Introduction

‘All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’

Anna Karenina [Leo Tolstoy, 1878 (1939)]

The postpartum period is a time of elevated risk for developing major depression, with a 3-fold increased risk of hospital admission in the first 2 months after childbirth compared with 1 year after delivery (Munk-Olsen et al. 2006). If not promptly detected and treated, postpartum maternal depression has a negative impact on the well-being of the mother and the development of the child, with suicide a major cause of maternal death (Cantwell et al. 2011).

Universal screening is recommended in many countries worldwide (Meltzer-Brody, 2011) and has been most recently suggested by the US Preventative Services Task Force (O’Connor et al. 2016). There are, however, still significant barriers to diagnosis and treatment of postpartum depression, with about 50% of cases going undetected (Bauer et al. 2014). Problems with trust and acceptance are the most reported cause of undisclosed depression, with less than 20% of women admitting they are completely honest with their health care providers about their depressive symptoms (Boots Family Trust, 2013). Health professionals also report that cultural barriers, including not only language, but also fear of incompetence, inadequate assessment tools, and the experience of cultural uncertainty (Teng et al. 2007), may prevent them from discussing mental health issues with the mother (Boots Family Trust, 2013).

Although there is robust evidence that the prevalence of postpartum depression varies across socio-economic levels [Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, 2015], we do not know if and how cultural influences make an impact on the expression of depression in the postpartum period. Knowledge of whether the disclosure of depressive symptoms in new mothers differs across cultures could improve detection and provide new insights into the determinants of postpartum depression. Moreover, it is a necessary step to evaluate the universal use of screening measures in research and clinical practice.

Culture is a notoriously difficult term to define, with 164 different definitions counted by Kroeber & Kluckhohn (1952). Research about cultural variations of inner psychological experiences challenges the traditional biomedical paradigm and its methodology. Culture is a complicated matrix of interplaying elements. However, biomedical research usually identifies it with nationality and infers that differences in the rates of a disorder across countries are due to cultural differences (Chentsova-Dutton et al. 2014). This approach may be misleading. For example, an epidemiological survey conducted in the UK found that black Caribbean women have the same rates of above-threshold postpartum depression scores as white women (Edge & Rogers, 2005). An in-depth qualitative analysis, however, found that postpartum depression was under-reported by black Caribbean women, who rejected the concept of postpartum depression because it fails the cultural imperative of being ‘strong’ and because of their tendency to have a pragmatic approach towards problems (Edge & Rogers, 2005).

Race is the cultural factor most commonly investigated in relation to depression, especially in the perinatal period. However, other cultural factors, including education, may influence the way postpartum depressive symptoms are experienced and reported by women. The relationship between education and the expression of major depression is poorly understood. Education may influence the subjective experience, self-awareness or the acceptance, and therefore disclosure, of psychiatric symptoms and help-seeking behaviours and has been shown to contribute to a less stigmatizing view of mental health (Cook & Wang, 2010). Together with other socio-economic factors education may also modulate the maturation of specific brain regions involved in mood disorders, such as the prefrontal cortex (Shonkoff et al. 2009). Studies in the general adult population, however, have led to inconsistent results and highlighted the complexity of the relationship between education and depression (Gan et al. 2012). Moreover, there are no studies investigating the impact of education in the expression of postpartum depression.

Cultural psychiatry usually focuses on ‘exotic lands’ and neglects Western nations (Cox, 1988; Kumar, 1994; Alarcón, 2009). Moreover, there is the general assumption that Western cultures are homogeneous and that there are no significant differences in psychiatric disorders across Europe and the USA. However, factors associated with maternal depression, including work and environmental demands (Dagher et al. 2011), access to universal maternity leave (Dagher et al. 2014), health care (Kozhimannil & Kim, 2014) and financial security (Kozhimannil & Kim, 2014), are regulated and influenced by local policies that differ across countries. For example, European social policies differ from country to country, but, contrary to the USA, all countries provide some form of paid universal maternity leave and free health care (Ray et al. 2010).

In the current study we therefore investigated cultural aspects beyond nationality and their impact on depression beyond disease prevalence. We explored whether education, ethnicity/race and continent influenced the expression of postpartum depression. The key question was: does the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the most widely employed screening tool for postpartum depression, measure the same underlying construct across cultural groups?

Method

Sample

Data were gathered from the PACT consortium. The PACT consortium was created to aggregate information collected by different centres in a large, international, coherent dataset that would allow for novel investigations in the genetics and phenomenology of perinatal depression. Detailed description of data collection and aggregation across sites is provided elsewhere [Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, 2015].

In brief, anonymous information on 17 912 parous women, both cases with postpartum depression and controls, was submitted to PACT by 19 institutions from seven countries.

Inclusion criteria for the current study were: (1) information on ethnicity/race or education or both; (2) individual item data on the EPDS available. If repeated records for a single participant were submitted, due to the longitudinal prospective design of the original study, the highest EPDS score was used, consistent with previous research [Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, 2015].

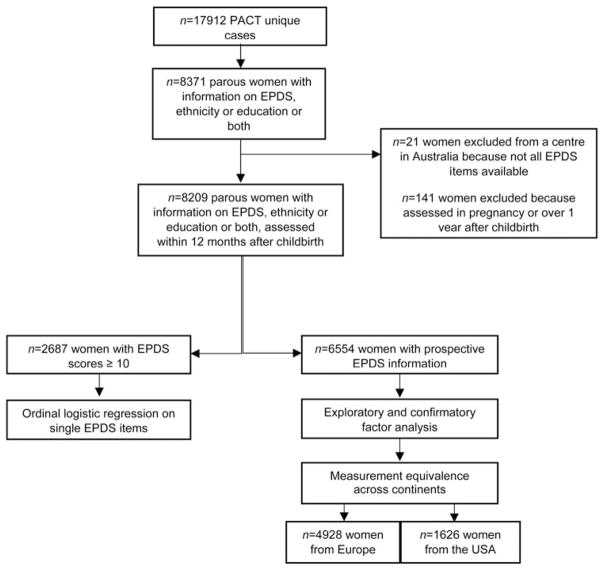

Fig. 1 shows the sample flowchart and analytic plan. The sample used for the current analyses consisted of 1635 women living in the USA (Arkansas, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina and Pennsylvania) and 6574 in Europe (103 in France, 1646 in Sweden and 4825 in two different sites in Rotterdam, the Netherlands). The English (Cox et al. 1987), Dutch (Pop et al. 1992), French (Guedeney & Fermanian, 1998) and Swedish lifetime (Meltzer-Brody et al. 2013) versions of the EPDS were used. Validation studies of the French and Swedish versions recommended a lower cut-off score than that of the original study (Cox et al. 2014).

Fig. 1.

Sample flowchart and analytic plan. PACT, Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Table 1 provides additional information on the sampling frame.

Table 1.

Site location, design, enrolment period, setting and language of EPDS

| Institution | Country | Assessment of postpartum symptoms | Repeated-measures design | Recruitment settinga | Language of EPDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Rochester | USA | Prospective | Yes | Obstetric clinics | English |

| University of Paris | France | Prospective | Yes | Multiple | French |

| Johns Hopkins | USA | Prospective | Yes | Multiple | English |

| University of Massachussets | USA | Prospective | No | Obstetric clinics | English |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | USA | Prospective | Yes | Multiple | English |

| University of Arkansas/Emory | USA | Prospective | Yes | Multiple | English |

| Karolinska Institute | Sweden | Retrospective | No | Swedish Twin Community | Swedish |

| National Institute of Mental Health | USA | 90% Prospective | No | Multiple | English |

| Erasmus | The Netherlands | Prospective | No | Psychiatric clinics | Dutch |

| Northwestern | USA | Prospective | Yes | Multiple | English |

| Erasmus | The Netherlands | Prospective | No | Community | Dutch |

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Multiple: psychiatric clinics, obstetric clinics, community, advertisements.

Variable definitions

The EPDS is the most widely used screening tool for postpartum depression in the world (Cox et al. 2014). Its 10 items are scored on an ordinal scale from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating worse symptomatology. There is limited consensus on the best threshold to define postpartum depression. The precision or validity of the threshold score was not problematic for this study, as we were interested in the expression of the depressive symptoms rather than in the prevalence of the disorder. Consequently, in the analyses on the different prevalence and severity of single EPDS items as a function of culture in women with significant symptomatology, we included as cases all women who had scored 10 or higher at the EPDS, consistent with the literature [Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, 2015].

Racial/ethnic groups were reported and defined according to the US census guidelines (http://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html). Women were categorized as having origin in any of the original people of:

Europe, the Middle East or North Africa (in this paper referred as ‘white’, according to the US census guidelines)

Black racial groups of Africa (‘black’)

Far East, Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent (‘Asian’)

Although the concept of race is separate from the concept of Hispanic origin, women were classified as ‘Latina’ if they were from Spanish-speaking countries of Central or South America, including the Dominican Republic and Cuba

‘Other’ if did not meet any of the criteria above or were of mixed race

Given that the educational systems differ across countries, we considered three broad ordinal categories: 12 years or fewer; 13–16 years; graduate or professional degree.

Whether the woman received money or financial aid from a government- or state-provided welfare/benefit/assistance programme or service was used as a proxy for low-income status.

Statistical analyses

Our research integrated two lines of enquiry, in which differences across ethnicities/races, education attainment and continent were explored.

First, we used ordered logistic regression to explore whether single EPDS items were expressed with greater prevalence and severity as a function of culture in a sample of 2687 women who scored 10 or above at the EPDS. Models were estimated with the polr command from the MASS package in R (Venables & Ripley, 2003). Proportional odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on a model using the score at each EPDS item as independent ordinal variable, ethnicity/race, education as a three-level ordinal variable, continent, EPDS total score, and study design as covariates and white race and Europe as reference categories.

We then examined the factor structure of the EPDS and tested its measurement invariance to quantitatively establish whether the EPDS had similar meanings across cultures. Factor analysis assumes that the observed score on a scale is a measure of one or more latent variables, inferred through statistical analysis.

There is no consensus on the factor structure of the EPDS. We therefore explored the factor structure of EPDS on a random subsample of 1164 women. Then, informed by past research and by our exploratory factor analysis, we tested a series of baseline models by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Brown, 2015). The baseline CFA models were fit using the cfa function from the package lavaan (http://lavaan.ugent.be). The diagonally weighted least-squares method was applied to estimate the model parameters and the full weight matrix to compute robust standard errors, and a mean- and variance-adjusted test statistic. We used robust fit indices [the robust standardized root mean square residual (SRMR*), the robust root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA*) and its 90% CI, and the robust comparative fit index (CFI*)] to assess how well the models captured the covariance between all the EPDS items in the model. The following cut-off values were employed: CFI* ≥0.90, RMSEA* ≤0.08, and SRMR*≤0.08 for acceptable fit and CFI* ≥0.95, RMSEA* ≤0.05, and SRMR*≤0.05 for good fit. The model with the best statistical properties and pragmatic relevance was then selected and used to test the measurement invariance of the EPDS.

In order to quantitatively test whether the EPDS items had similar meanings across cultures, we employed measurement invariance, a statistical method that allows to test whether the items of a scale measure the same underlying construct in different groups (Millsap, 2011).

Measurement equivalence (or, in statistical terms, measurement invariance) is tested within the structural equation modelling framework by using multi-group CFA (Millsap, 2011; Hirschfeld & von Brachel, 2014). It is based on the idea that a psychometric scale should work in the same way across varied conditions that are irrelevant to the measured attribute (Millsap, 2011; Hirschfeld & von Brachel, 2014). It consists of a sequence of hierarchical nested models, each defined by a more restrictive set of requirements: weak invariance (i.e. equal factor loadings); strong invariance (i.e. equal loadings and intercepts); strict invariance (equal loadings + intercepts + residuals) and allows the detection of bias related to the person’s membership to a group (21) (in the current study: ethnicity, continent, education). Models were compared in pairs and measurement invariance was rejected when the difference between robust CFIs (Δ*CFI) was above the cut-off value of 0.01.

Recall bias can potentially influence the retrospective report of depressive symptoms. Therefore, we only included 6554 women assessed in prospective studies for the measurement invariance testing.

Results

Data on 8209 women meeting the inclusion criteria were available for the current analysis. Sample characteristics are presented in Table 2. The majority of the subjects were white, with no differences between studies conducted in Europe (n = 3687, 76.5%) and those conducted in the USA (n = 1226, 75.0%). Black women were equally represented across continents [17.3% (n = 832) in Europe and 18.3% (n = 299) in the USA]. However, there were statistically significant differences in the other minority groups represented across sites and between Europe [no Latinas, 6.2% (n = 300) Asian] and the USA [2.5% (n = 41) Latinas, 1.9% (n = 31) Asian, χ2 = 269.2505, degrees of freedom (df) = 4, p < 0.001], reflecting differences in the population structure between Europe and the USA. There were also geographical differences in education attainment, with 38.2% (n = 2486) of the European participants having 12 years or fewer of education, compared with 18.5% (n = 133) of the US counterpart (χ2 = 111.295, df = 2, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (n = 8209)

| Europe

|

USA

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median | Min | Max | n | Median | Min | Max | |

| Age at interview, years | 6575 | 33 | 15 | 68 | 1635 | 31 | 18 | 46 |

| Date of completion of EPDS, days after childbirtha | 4535 | 85 | 9 | 294 | 1625 | 37 | 0 | 365 |

| Race or ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||

| Asian | 300 | (6.2) | 31 | (1.9) | ||||

| Black | 832 | (17.3) | 299 | (18.3) | ||||

| Latina-Hispanic | 0 | 41 | (2.5) | |||||

| White | 3687 | (76.5) | 1226 | (75.0) | ||||

| Other | 2 | (<0.1) | 38 | (2.3) | ||||

| Education attainment, n (%) | ||||||||

| 12 years or fewer | 2486 | (38.2) | 133 | (18.5) | ||||

| 13–16 years | 2548 | (39.1) | 351 | (48.9) | ||||

| Graduate or professional degree | 1475 | (22.7) | 234 | (32.6) | ||||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Married or live as married | 5648 | (87.5) | 1108 | (69.0) | ||||

| Lives alone: single, divorced, separated, widowed | 806 | (12.5) | 498 | (31.0) | ||||

| Design of the study in which the woman was recruited, n (%) | ||||||||

| Prospective | 4928 | (75.0) | 1626 | (99.4) | ||||

| Retrospective | 1646 | (25.0) | 9 | (0.6) | ||||

| Low-income status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Yes | 531 | (12.8) | 22 | (19.8) | ||||

| No | 3631 | (87.2) | 89 | (80.2) | ||||

Min, Minimum; max, maximum; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Includes only prospectively evaluated women.

We have previously reported EPDS item response probabilities by site [Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, 2015].

The proportion of missing values was below 1% in all sites, with the exception of the two sites in the Netherlands, one where one out of 45 subjects did not respond to items 9 and 10 and the other where 38.5% of the sample did not have information on item 10. We therefore excluded the data from the latter centre in the analyses on thoughts of self-harm. In the ordinal logistic regression, there were no statistically significant differences in overall item non-response between women with depression and those without, and across recruitment sites, race and education level groups.

Cross-cultural differences in reporting depression

We compared responses to each EPDS item in a sub-sample of 2687 women with EPDS scores of 10 or higher examining race, educational attainment and continent. Complete information for all covariates was available for 2044 women. Specifically, there were 1502 white, 429 black, 77 Asian and 36 Latina women; 874 women with 13 years or fewer of education, 698 with 14–16 years and 327 with a graduate or professional degree; and 1254 women from Europe and 1433 from the USA. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.005 due to multiple comparisons.

Table 3 shows the proportional ORs obtained from the ordered regression analyses on single EPDS items.

Table 3.

Association between scores of single EPDS items and ethnicity/race, education and continent in 2687 women with postnatal depressiona

| Item | Black | Hispanic-Latina | Asian | Education | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| OR (0.5–99.5% CI) | OR (0.5–99.5% CI) | OR (0.5–99.5% CI) | OR (0.5–99.5% CI) | OR (0.5–99.5% CI) | ||

| 1 | I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of thingsb | 1.04 (0.715–1.500) | 2.33 (0.845–6.452)* | 0.85 (0.461–1.558) | 0.76 (0.560–1.027)* | 0.19 (0.130–0.268)*** |

| 2 | I have looked forward with enjoyment to thingsb | 1.11 (0.772–1.598) | 1.81 (0.634–5.166) | 0.93 (0.509–1.693) | 0.58 (0.426–0.780)*** | 0.21 (0.146–0.295)*** |

| 3 | I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong | 1.31 (0.916–1.890) | 3.15 (1.142–8.685)*** | 1.26 (0.687–2.304) | 0.79 (0.592–1.060)* | 0.36 (0.259–0.505)*** |

| 4 | I have been anxious or worried for no good reason | 0.92 (0.632–1.333) | 0.71 (0.258–1.938) | 1.00 (0.531–1.889) | 0.78 (0.574–1.051) | 0.27 (0.184–0.388)*** |

| 5 | I have felt scared or panicky for no very good reason | 0.86 (0.594–1.239) | 1.09 (0.353–3.376) | 1.23 (0.652–2.315) | 1.37 (1.016–1.860)** | 1.00 (0.701–1.414) |

| 6 | Things have been getting on top of me | 0.97 (0.659–1.425) | 0.93 (0.320–2.693) | 0.96 (0.494–1.874) | 1.27 (0.929–1.749) | 0.32 (0.221–0.460)*** |

| 7 | I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping | 1.25 (0.846–1.831) | 0.56 (0.169–1.839) | 0.75 (0.392–1.427) | 1.03 (0.745–1.432) | 3.82 (2.665–5.501)*** |

| 8 | I have felt sad or miserable | 0.99 (0.654–1.500) | 0.80 (0.236–2.730) | 1.01 (0.497–2.041) | 1.21 (0.863–1.690) | 1.89 (1.305–2.741)*** |

| 9 | I have been so unhappy that I have been crying | 0.81 (0.545–1.214) | 0.52 (0.169–1.621) | 0.59 (0.196–1.620) | 1.53 (1.097–2.143)*** | 2.34 (1.615–3.394)*** |

| 10 | The thought of harming myself has occurred to me | 0.34 (0.174–0.680)*** | 0.32 (0.093–1.110)* | 0.84 (0.174–4.019) | 3.21 (1.926–5.348)*** | 49.45 (18.915–129.285)*** |

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Proportional OR and CIs were calculated on a model using ethnicity/race, education, EPDS total score, and study design as covariates. White race and Europe were the reference categories; education was treated as an ordinal variable.

Reverse-scored items.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.005.

Compared with white women, Latinas were significantly more likely to report higher severity of excessive self-blame and feelings of guilt (item 3: t = 2.912; p = 0.004). Analysis on self-harming thoughts (item 10) was conducted on a subsample of 2082 women, as we excluded a centre in the Netherlands, because of the high proportion (38.5%) of missing values. Black women were less likely than white women to report higher severity of self-harming thoughts (item 10: t = −4.1911; p < 0.001). There were no other statistically significant differences between races/ethnicities.

Results did not change when analyses on ethnicity/race were conducted separately on European (excluding Latinas) and US (excluding Asian women) subsamples.

Less educated women were significantly more likely to report lack of enjoyment (i.e. anhedonia, item 2: t = −4.6982; p < 0.001), while educational attainment was positively associated with crying (item 9: t = 3.2866; p = 0.001) and thoughts of self-harm (item 10: t = 5.8802; p < 0.001).

There was a strong association between EPDS items and continent even when analyses were corrected for education, study design and EPDS total score. Women from Europe reported higher scores of anhedonia (item 1: t = −11.976, p < 0.001; item 2: t = −11.462, p < 0.001), self-blaming (item 3, t = −7.8466, p < 0.001) and anxiety (item 4: t = −9.098, p < 0.001 and item 6: t = −8.0269, p < 0.001), while women from the USA disclosed more severe insomnia (item 7: t = 9.5428, p < 0.001), depressive feelings (item 8: t = 4.4252, p < 0.001 and item 9: t = 5.9036, p < 0.001) and thoughts of self-harming (item 10, t = 10.4617; p < 0.001).

A further analysis was conducted on a subsample of women who scored 13 or higher at the EPDS with similar results.

Cross-cultural differences in the latent structure of postpartum depression

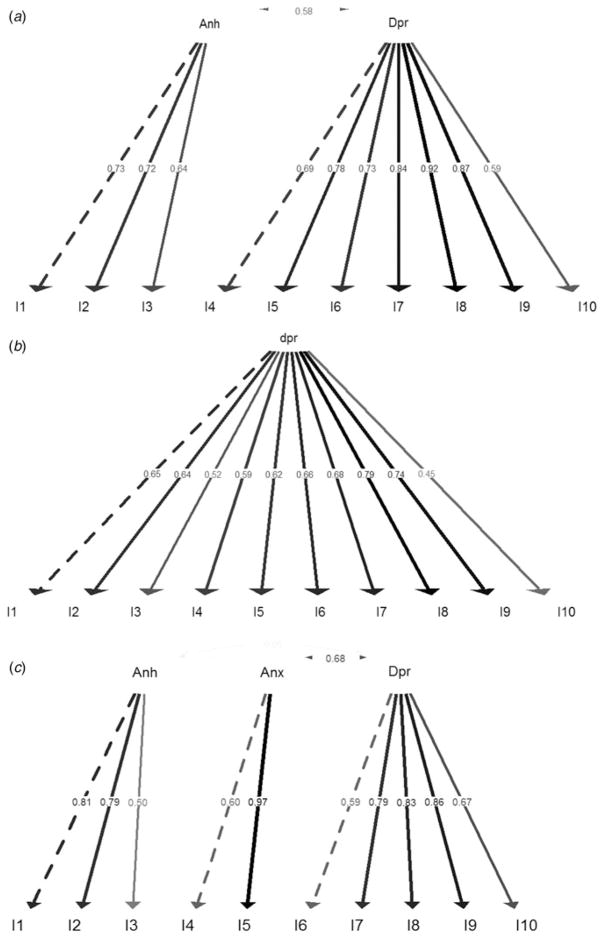

The scree plot suggested retaining three factors. After exploring the unrotated and rotated factor matrices, we opted for a varimax rotation. Two factors were highly correlated (0.87). We therefore opted for a two-factor model (Fig. 2a), including anhedonia (items 1–3) and depression (items 4–10). The two-factor model we obtained from our initial exploratory factor analysis had the best fit among models including all 10 EPDS items (robust indices: χ2 = 3405.457, df = 34, CFI* = 0.920, RMSEA* = 0.145, SRMR* = 0.065) and was chosen for the analyses of measurement invariance.

Fig. 2.

Factor models obtained from exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: (a) on the whole sample of prospectively recruited women; (b) on prospectively recruited European women; (c) on prospectively recruited US women. Item 4 (I4) had loadings close to zero in the European sample. Anh, Anhedonia; Depr, depression; Anx, anxiety.

The EPDS did not have the same factor structure in US and European women (weak invariance Δ*CFI = 0.145, strong invariance Δ*CFI = −0.012, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.185). Using exploratory analysis and CFA we parsimoniously chose a one-factor model for Europe (Fig. 2b – robust indices: χ2 = 1055.139, df = 35, CFI* = 0.898, RMSEA* = 0.099, SRMR* = 0.060) and a three-factor model for the USA, despite the poor fit (Fig. 2c – robust indices: χ2 = 1255.970, df = 32, CFI* = 0.885, RMSEA = 0.154, SRMR = 0.076). When analyses by country were conducted on the three European centres in the Netherlands and in France, the EPDS showed measurement equivalence (weak invariance Δ*CFI = −0.007, strong invariance Δ*CFI = 0.011, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.013).

Given the differences in ethnic distribution and EPDS factor structure between Europe and the USA, we analysed measurement invariance separately for the two geographical regions. The EPDS was measurement equivalent across ethnic/racial groups (i.e. the construct measured by the EPDS was made up of the same number of factors, with equal factor loadings, intercept and variance across groups. For Europe: black v. white: weak invariance Δ*CFI = −0.022, strong invariance Δ*CFI = 0.006, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.012; Asian v. white: weak invariance Δ*CFI = −0.029, strong invariance Δ*CFI = 0.001, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.003; for the USA: black v. white: weak invariance Δ*CFI = 0.007, strong invariance Δ*CFI = 0.006, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.007; Latina v. white: weak invariance Δ*CFI = −0.014, strong invariance Δ*CFI < 0.001, strict invariance Δ*CFI = −0.004).

Given the evidence of differences in the factor structure between Europe and the USA, we explored the factor structure of the EPDS across levels of education by continent. The EPDS was not measurement equivalent across levels of education in Europe (low v. high level: weak invariance Δ*CFI = 0.028, strong invariance Δ*CFI = 0.014, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.012), nor in the USA (low v. high level: weak invariance Δ*CFI = −0.017, strong invariance Δ*CFI = 0.030, strict invariance Δ*CFI = 0.012).

A further analysis was conducted in order to determine whether the effect of continent was driven by the differences in education attainment between USA and Europe. We found that within the same level of education the structure of the EPDS differed between Europe and the USA (Δ*CFI > 0.01).

Discussion

We found that level of education and continent (Europe or USA), much more than ethnicity/race, influenced the expression of postpartum depression on the EPDS. These results have important implications for the delivery of culturally specific and sensitive clinical care and warrant careful examination with specific attention paid to education and socio-political factors.

Education

According to our findings, less educated women with postpartum depression are less likely to report crying and thoughts of self-harm and are more likely to report anhedonia. Although there is robust evidence of the association between the prevalence of postpartum depression and low socio-economic status [Wisner et al. 2013; Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, 2015], we believe this is the first study to have systematically investigated the effect of education on the expression of postpartum depressive symptoms and on the psychometric properties of the EPDS. Further research is needed to replicate our findings and to understand the mechanisms by which education influences the disclosure of depressive symptoms.

Ethnicity and race

Despite the emphasis that is usually put on race/ethnicity in relation to cultural sensitivity, we did not find any major difference in the psychometric properties of the EPDS across racial/ethnic groups and only some differences in the disclosure of symptoms among depressed women. It is possible that the differences that are usually observed between white and minorities are due entirely to the differences in the socio-economic status, as suggested by the literature on disease prevalence (Comstock & Helsing, 1976; Dolbier et al. 2013).

Differences between European and American women

We found differences in the symptomatic manifestations of postpartum depression between European and American women. There is the general assumption that Western cultures are homogeneous and that there are no significant differences in psychiatric disorders across Europe and the USA. A recent study has corroborated this assumption and reported that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria for major depression in Europe and the USA are measurement equivalent (Kendler et al. 2015). However, many factors associated with postpartum depression, including work and environmental demands (Dagher et al. 2011), access to universal maternity leave (Dagher et al. 2014), health care (Kozhimannil & Kim, 2014) and financial security (Kozhimannil & Kim, 2014), are regulated and influenced by local policies that differ across countries. It is possible that the lack of universal paid maternity leave or access to health care in the USA influences the expression of psychopathology. Several studies conducted in the USA have suggested a relationship between short maternity leave and the prevalence of depressive symptoms (Chatterji & Markowitz, 2012; Dagher et al. 2014), but research on the impact of maternity leave on the phenomenology of postpartum depression is lacking. Interestingly the two European countries evaluated in the measurement invariance analyses, France and the Netherlands, have similar regulations (Ray et al. 2010). It is also possible that issues of linguistic and cultural understandings of metaphor could explain the differences found between the USA and Europe. The Dutch and French versions of the EPDS, however, had similar factor structures, despite the linguistic differences between the two European countries.

There is a dearth of studies investigating differences in stigma towards psychiatric illness in the USA and Europe. The World Mental Health Surveys reported a wide variability (9–40%) in the prevalence of stigma associated with mood disorders in the countries included in the current study (Alonso et al. 2008). Differences in prescribing patterns and attitudes toward psychotropic medications between Europe and the USA may reflect stigma and are indicative of how different countries approach treatment of perinatal depression. For example, prescribing of antidepressant medication during pregnancy markedly varies between the USA and Denmark [13% (Cooper et al. 2007) v. less than 2% (Munk-Olsen et al. 2012), respectively]. Similarly, a population-based survey found more favourable attitudes towards psychiatric medications in the USA as compared with Germany (Schomerus et al. 2014).

Implications for clinicians

Our results underscore the need for clinicians to be aware of the patient’s cultural perspective in the diagnostic process. Culture is a complex, multifaceted construct. Health care providers should not stereotype postpartum women on the basis of their ethnical/racial background; rather, they should explore the cultural milieu (including education) of the patient beyond ethnicity and race.

Postpartum women with lower levels of education may not disclose symptoms that usually trigger medical attention, such as crying and thoughts of self-harm. In these women, clinicians should focus on the presence of anhedonia and sensitively investigate other symptoms that may be present, but not disclosed, because they may be perceived as highly stigmatizing.

Implications for policy makers

According to our findings, the universal use of the EPDS requires careful consideration. Our results provide some preliminary evidence on the psychometric differences of the EPDS across contexts. The lack of measurement invariance can partially explain the heterogeneity in the previous validation studies of the EPDS (Eberhard-Gran et al. 2001; Gibson et al. 2009). Policy makers and clinicians should be aware that research evidence on postpartum depression may be influenced by the context in which they were obtained and that in screening for postpartum depression, one size does not necessarily fit all.

Implications for clinical research

The assumption that the EPDS universally measures the same construct can potentially lead to misclassification, invalid group comparisons, and erroneous conclusions about aetiology and risk factors (Gregorich, 2006; Gibson et al. 2009). It is possible that differences in the EPDS symptoms reported reflect differences in the pathogenesis of depression, with certain symptoms more likely to be triggered by environmental and social factors than others (Keller et al. 2007; Paykel, 2008).

Our findings open opportunities for new research into the effects of the socio-cultural environment on postpartum depression. According to our results, the context influences not only the disclosure of symptoms, but also the relationship between symptoms and, therefore, how depression manifests itself. In summary, we believe our findings reinforce the need for clinicians, researchers and policy makers to pay close attention to the importance of the context in both assessment and treatment planning for women with postpartum depression.

Strengths and limitations

Our study presents several strengths: (1) the broad definition of culture including country, ethnicity/race and level of education; (2) the application of measurement invariance to the expression of depressive symptoms; and (3) the use of a large, international dataset.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first international study on the cross-cultural differences in postpartum depression. Consequently, our findings need to be replicated and interpreted in light of the following limitations:

The self-reported symptoms on the EPDS do not necessary reflect the symptomatology that would be captured by a psychiatrist. Cultural bias, however, may also influence standardized measures used by clinicians (Chentsova-Dutton et al. 2014).

Because we found that the factor structure of the EPDS varies across levels of education and between continents, we could not disentangle actual differences in the psychopathology from those due to the different psychometric properties of the EPDS across groups.

The PACT dataset was created by aggregating data from different sites with different research protocols. Ascertainment biases and methodological differences across sites cannot be excluded. For example, it has been shown that the structure of the EPDS changes with the severity of depressive episode and responses at different time points may reflect different factor structures (Cunningham et al. 2014). For the factor and measurement invariance analyses we tried to minimize them by including only studies with a prospective design. Similarly, regression analyses on symptoms of depression were stratified for possible confounding factors, including study design, severity of symptomatology and country/language of administration of the EPDS. We included the EPDS total score as a covariate to capture severity of the symptomatology, and therefore partially account for possible recruitment bias and differences among sites. Although confounders cannot be excluded, it is encouraging that the two different approaches have led to consistent conclusions.

Our analyses included only 41Latinas, less than 1% of the total sample. The under-representation of Latinas in biomedical research is a well-known problem (Lara-Cinisomo et al. 2015). Our results need to be replicated in larger samples of Latinas, as the lack of an effect, especially in the measurement invariance analyses, may be due to the low statistical power.

There are other cultural and social factors, such as religion, family support and financial situation that are likely to influence the expression of postpartum depressive symptoms and should be considered by clinicians and researchers. We pragmatically chose education and race/ethnicity as they are stable and quantifiable characteristics, easily obtainable in clinical and research settings with limited time and human resources available. Similarly, we were not able to capture differences among ethnic subgroups or the effect of immigration status. Europe is heterogeneous, with different regulations and views on family and maternity. In this research, we examined only three northwest European countries. Our findings cannot be extended to other parts of Europe.

Conclusion

Our work suggests that culture influences the expression of postpartum depression. Level of education– more than race and ethnicity – has a significant impact on symptom profiles and on the underlying construct of depression among new mothers. Our findings of significant differences between the USA and Europe contrast the general assumption that Western culture is homogeneous.

The increasing cultural heterogeneity of societies together with the tendency towards globalization requires a culturally sensitive approach to patients, research and policies, that takes into account, beyond rhetoric, the context of a person’s experiences and the context in which the research is conducted.

Acknowledgments

A.D.F. is funded by a European Commission Marie Curie Fellowship (grant number 623932). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) supports T.M.-O., D.R.R., P.F.S. and S.M.-B. (1R01MH104468-01). K.M.S. (5K23MH086689), J.P. (K23 MH074799-01A2), V.B. (FP7-Health-2007 Project no 222963), M.O. (MH50524 NIMH), K.L.W. (5R01MH60335, NIMH, 5R01MH071825, 5R01MH075921 and 5-2R01MH057102), S.J.R. and H.T. (ZonMW 10.000.1003), and P.J.S. (ZIA MH002865-09 BEB). K. M.D. is supported by the NIMH (K23 MH097794), National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000161) and a Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research grant. C.N.E. has been supported by NIMH grants P50 MH099910, K23 MH001830, NIDA K24 DA030301, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and a young investigator award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. E.R.-B. is supported by the NIMH (K23MH080290) and a young investigator award from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation; G.A. and E.D. are supported by the French Ministry of Health (PHRC 98/001) and the Mustela Foundation. B. W.P. is supported by the Geestkracht program of the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (10-000-1002) and VU University Medical Centre, GGZ Geest, Arkin, Leiden University Medical Centre, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Centre in Groningen, Lentis, GGZ Fries land, GGZ Drenthe, IQ Healthcare, Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction. C.G. is supported by the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (UL1 TR000062) and Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (K12 HD055885). Z.N.S. is supported by the NIH (P50 MH-77928 and P50 MH 68036). I.J. is supported by the National Centre for Mental Health Wales. P.L., P.K.E.M. and A.V. are supported by the Swedish Ministry for Higher Education, the Swedish Medical Research Council (K2014-62X-14647-12-51 and K2010-61P-21568-01-4), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Brain Foundation and the NIMH (K23 MH085165).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Alarcón RD. Culture, cultural factors and psychiatric diagnosis: review and projections. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:131–139. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J, Buron A, Bruffaerts R, He Y, Posada-Villa J, Lepine J-P, Angermeyer MC, Levinson D, de Girolamo G, Tachimori H, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Ormel J, Scott KM, Gureje O, Haro JM, Gluzman S, Lee S, Vilagut G, Kessler RC, Von Korff M World Mental Health Consortium. Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118:305–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, Iemmi V, Adelaja B. Costs of Perinatal Mental Health Problems. London School of Economics and the Centre for Mental Health; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boots Family Trust. Boots Family Trust Perinatal Mental Health Report. 2013 ( http://www.bftalliance.co.uk/the-report/)

- Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2. The Guilford Press; New York and London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, Garrod D, Harper A, Hulbert D, Lucas S, McClure J, Millward-Sadler H, Neilson J, Nelson-Piercy C, Norman J, O’Herlihy C, Oates M, Shakespeare J, de Swiet M, Williamson C, Beale V, Knight M, Lennox C, Miller A, Parmar D, Rogers J, Springett A. Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji P, Markowitz S. Family leave after childbirth and the mental health of new mothers. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2012;15:61–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chentsova-Dutton YE, Ryder AG, Tsai J. Understanding depression across cultural contexts. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of Depression. 3. Guilford; New York: 2014. pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock GW, Helsing KJ. Symptoms of depression in two communities. Psychological Medicine. 1976;6:551–563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TM, Wang J. Descriptive epidemiology of stigma against depression in a general population sample in Alberta. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA. Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;196:544.e1–544.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Holden J, Henshaw C. Perinatal Mental Health: The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Manual. 2. RCPsych Publications; London: 2014. revised edn. [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL. Childbirth as a life event: sociocultural aspects of postnatal depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum. 1988;344:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb09005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham NK, Brown PM, Page AC. Does the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale measure the same constructs across time? Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2014;18:793–804. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Dowd BE. Maternity leave duration and postpartum mental and physical health: implications for leave policies. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2014;39:369–416. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2416247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Dowd BE, Lundberg U. Postpartum depressive symptoms and the combined load of paid and unpaid work: a longitudinal analysis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2011;84:735–743. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0626-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbier CL, Rush TE, Sahadeo LS, Shaffer ML, Thorp J Community Child Health Network Investigators. Relationships of race and socioeconomic status to postpartum depressive symptoms in rural African American and non-Hispanic white women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013;17:1277–1287. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Ove Samuelsen S. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:243–249. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge D, Rogers A. Dealing with it: black Caribbean women’s response to adversity and psychological distress associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and early motherhood. Social Science and Medicine (1982) 2005;61:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Z, Li Y, Xie D, Shao C, Yang F, Shen Y, Zhang N, Zhang G, Tian T, Yin A, Chen C, Liu J, Tang C, Zhang Z, Liu J, Sang W, Wang X, Liu T, Wei Q, Xu Y, Sun L, Wang S, Li C, Hu C, Cui Y, Liu Y, Li Y, Zhao X, Zhang L, Sun L, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Ning Y, Shi S, Chen Y, Kendler KS, Flint J, Zhang J. The impact of educational status on the clinical features of major depressive disorder among Chinese women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:988–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;119:350–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorich SE. Do self-report instruments allow meaningful comparisons across diverse population groups? Testing measurement invariance using the confirmatory factor analysis framework. Medical Care. 2006;44:S78–S94. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245454.12228.8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedeney N, Fermanian J. Validation study of the French version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): new results about use and psychometric properties. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 1998;13:83–89. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(98)80023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld G, von Brachel R. Multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis in R – a tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2014;19:1–12. ( http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=19&n=7) [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1521–1529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. quiz 1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Li Y, Lewis CM, Breen G, Boomsma DI, Bot M, Penninx BWJH, Flint J. The similarity of the structure of DSM-IV criteria for major depression in depressed women from China, the United States and Europe. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45:1945–1954. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil KB, Kim H. Maternal mental illness. Science. 2014;345:755–755. doi: 10.1126/science.1259614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber AL, Kluckhohn C. Culture: a critical review of concepts and definitions. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archeology and Ethnology. 1952;47:223. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R. Postnatal mental illness: a transcultural perspective. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1994;29:250–264. doi: 10.1007/BF00802048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Wisner KL, Meltzer-Brody S. Advances in science and biomedical research on postpartum depression do not include meaningful numbers of Latinas. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health/Center for Minority Public Health. 2015;17:1593–1596. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S. New insights into perinatal depression: pathogenesis and treatment during pregnancy and postpartum. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2011;13:89–100. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/smbrody. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Boschloo L, Jones I, Sullivan PF, Penninx BW. The EPDS-Lifetime: assessment of lifetime prevalence and risk factors for perinatal depression in a large cohort of depressed women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2013;16:465–473. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE. Statistical Approaches to Measurement Invariance. Routledge; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Gasse C, Laursen TM. Prevalence of antidepressant use and contacts with psychiatrists and psychologists in pregnant and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;125:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders. JAMA. 2006;296:2582–2589. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:388–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES. Basic concepts of depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;10:279–289. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/espaykel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop VJ, Komproe IH, van Son MJ. Characteristics of the Edinburgh Post Natal Depression Scale in the Netherlands. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1992;26:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium. Heterogeneity of postpartum depression: a latent class analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Gornick JC, Schmitt J. Who cares? Assessing generosity and gender equality in parental leave policy designs in 21 countries. Journal of European Social Policy. 2010;20:196–216. [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Baumeister SE, Mojtabai R, Angermeyer MC. Public attitudes towards psychiatric medication: a comparison between United States and Germany. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:320–321. doi: 10.1002/wps.20169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce W, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng L, Robertson Blackmore E, Stewart DE. Healthcare worker’s perceptions of barriers to care by immigrant women with postpartum depression: an exploratory qualitative study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2007;10:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstoy L. Anna Karenina. Oxford University Press/Humphrey Milford; Oxford: 1878 [1939]. [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4. Springer; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Sit DKY, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, Eng HF, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR, Costantino ML, Confer AL, Moses-Kolko EL, Famy CS, Hanusa BH. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:490–498. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]