Abstract

Professionalism and performance are now the focus of assessment in postgraduate medical training and revalidation in the UK. Ethical decision making and clinical reasoning are key elements for practising gastroenterologists to master. The skills required to reflect, teach and appraise ethical decision making are central to the effectiveness of relationships with patients and colleagues. A framework is presented to enable gastroenterologists to reflect and learn from everyday ethical dilemmas in clinical practice.

Keywords: Artificial Nutrition Support, Endoscopic Gastrostomy, Endoscopy, Nutritional Support, Psychology

Introduction

Ethical dilemmas in gastroenterology are common and include training in endoscopy, gastrostomy tube placement, end of life decisions and informed consent.1 The teaching of reflective ethical practice has traditionally not been a central focus in postgraduate gastroenterology education programmes but is now becoming increasingly important.2–5 Drivers for this change in focus include technological advances in areas such as genetics, organ donation and critical care; the changing physician-patient and trainer-trainee relationship; and external pressures including national guidelines, regulatory bodies, media involvement, financial constraints and political opinion.1

The method of teaching clinical ethics has been debated over the last 30 years. Features important to ethics teaching include being embedded in familiar clinical situations, being multidisciplinary and being student-centred.6 Ethical training for postgraduate gastroenterologists may largely occur in the informal or hidden curriculum, through professional exchanges and role modelling.7 8 As methods of learning in UK postgraduate gastroenterology increasingly adopt workplace-based events, focusing on performance appraisal and supported by ethically trained supervisors; the necessity for trainees and supervisors to be familiar with reflective and critical appraisal of ethical practice becomes clear.9 The role of simulation learning for human factors training, including ethical decision making, is also being increasingly explored in gastroenterology.10 In continuing medical education, revalidation will encompass personal attributes and values, ethical decision making and communication skills, in addition to the highly technical skills demanded of most practising gastroenterologists.11

The SLICE framework

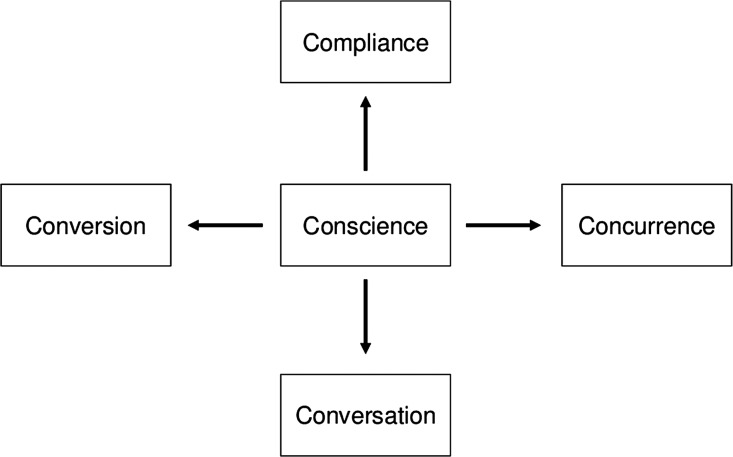

The Structured Learning in Clinical Ethics (SLICE) model includes five domains to help navigate around your moral or ethical compass12 (figure 1). This paper describes each domain of the SLICE framework and its relevance to everyday ethical dilemmas in gastroenterology. Finally, two case examples are provided to illustrate how the framework can help support reflection, appraisal and professional development.

Figure 1.

The Structured Learning in Clinical Ethics (SLICE) framework for clinical ethics teaching.

Conscience

Conscience is at the heart of the moral compass. It is your inner voice and symbolises your moral principles such as honesty, trustworthiness and integrity. It correlates closely with probity, the foundation stone of professionalism.13 In early professional life, ethical principles are often grounded in non-medical settings: for example, cultural, religious or social upbringing. Through postgraduate training and continuing medical education, moral principles and judgements are refined. Role modelling plays a significant and important part in ethical and professional development.14 Good role models are likely to have strong ethical principles, clinical reasoning and communication skills and have happy, committed and positive junior staff.15 In contrast, poor ethical practice can lead to decreasing job satisfaction, motivation and moral erosion in colleagues.7 15 Negative role modelling can be influenced by institutional and organisational factors such as inadequate time provided for teaching activities, or lack of recognition for exemplary teaching.

Compliance

Compliance with medicolegal issues is an element of sound ethical practice; it protects patients from unlawful practice and maintains public trust in the medical profession. Deviance from accepted law, policy or regulation, may reflect a cavalier, or indeed, criminal tendency that may put patients at risk. In England, gastroenterologists work alongside statute law, common law, national and local guidelines and policies. Statute law relevant to the modern gastroenterologist includes the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2006, the Human Rights Act 1998, the Data Protection Act 1998 and the Mental Capacity Act 2005, including advance decisions.16 Clinical ethics committees are increasingly being established in UK hospitals to support clinicians with legal and ethical decision making.17 The British Society of Gastroenterology and the National Institute of Clinical Excellence produce guidelines aimed to provide best evidence ethical care for patients. Local guidelines and policies aimed at supporting patient care include complaint policies and information technology governance. In educational settings, ethical practice includes compliance with guidelines for induction, supervision, teaching and feedback.

Concurrence

Concurrence is the acceptance of and respect for others’ moral viewpoints. This is important for creating flexible, open and equal opportunities for colleagues and patients. In gastroenterology, for example, this may be particularly important when treating a Jehovah's Witness with a large gastrointestinal bleed when standard practice of blood transfusion may be against the moral standpoint of the patient. Many hospitals now have access to support from Jehovah's Witness Hospital Liaison Committees established to build more collaborative and ethical care for Witnesses.18 Other examples of concurrence include accepting the patient's wish for treatment in a local hospital because it is closer to home, even if that hospital does not offer the full range of services; or respecting and acknowledging religious or cultural beliefs and values such as Ramadan. In more exceptional situations, the concept of conscientious objection might be explored.19

Conversation

Where the domain of concurrence is accepting and respecting others’ viewpoints, conversation allows the clinician to openly discuss different ethical viewpoints without imposing their own on others. Conversation involves the skills of active listening and empathy and overlaps with communication or interpersonal skills teaching for clinicians. Where divergent ethical views are expressed, sensitive conversation skills which are neutral and non-judgemental can help facilitate effective dialogue.20 For example, a terminal cancer patient who expects radical surgery despite its clinical futility; or the patient who wishes a female doctor when one is not available. Reflecting on conversations with patients or colleagues where different moral views are expressed can improve our own moral development and enhance patient care by anticipating differing moral and ethical views and practising our skills in dealing with them.

Conversion

Conversion is perhaps the most advanced domain of skills in clinical ethics. Conversion requires appropriate conscience, compliance, concurrence and conversation and the ability to accommodate others’ viewpoints, while trying to enlighten them to other possibilities. In gastroenterology, this may involve convincing the family of a patient with dementia that gastrostomy feeding is not in her best interests; or explaining to a patient the need for further endoscopies when previous experiences have been distressing or painful.

Case example 1

An 83-year-old woman is admitted to a general medical ward with agitation and a lower urinary tract infection. She lives with her elderly husband who is finding it difficult to cope with her confusion. She has three children, none of whom live locally and are not able to provide support. The family was told that the patient had early onset dementia 4 years ago. No specific treatments or social support have been started. The patient is underweight and appears dehydrated on admission. The specialty registrar in gastroenterology receives a request for a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube insertion. He asks you, the gastroenterology consultant, for advice about how to reach decisions about PEG feeding in patients with dementia. You decide to hold a small group teaching session for your specialty trainees on PEG tube insertion in patients with dementia and use the SLICE model as a framework for discussing the ethical elements (table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of ethical considerations for the insertion of PEG tubes in patients with dementia

| Conscience | Assesses patients with dementia for nutritional deficiencies on an individual basisInvolves a multiprofessional nutrition team wherever possible in nutritional support decision makingAssesses patients promptly and makes timely decisions |

| Compliance | Complies with local protocols for multidisciplinary team decisions regarding nutritional supportComplies with the Mental Capacity Act 2005, including valid advance decisions and lasting powers of attorney |

| Concurrence | Acknowledges and respects patient's and family's views on appropriateness of PEG tube insertion |

| Conversation | Communicates effectively with patients, carers and family about risks, benefits and alternatives of PEG feeding in demented patientsMaintains balanced/neutral viewpoints where possibleEmpathises with patients, families and carers when discussing nutritional support |

| Conversion | Explains alternatives to PEG feeding (eg, hand feeding and oral modifications)Allows time for family to consider alternatives providedAble to negotiate sensitively around previous information given to family about nutritional support |

Case example 2

A 45-year-old man attends for an outpatient gastroscopy. He requests sedation but has no escort available. The admitting endoscopy nurse explains he should have throat spray if he does not have an escort. The patient is upset because he understood he would be sedated and requests to speak to the doctor. You are a senior Specialty Trainee, competent in diagnostic gastroscopy. You have a conversation with the patient, explaining the reasons for the policy about escorts for sedated patients. You explain the risks and benefits of having throat spray only; and offer him the opportunity to rebook when he can arrange for an escort. He decides to proceed with the procedure under throat spray. The procedure is uneventful and the patient leaves shortly afterwards. You reflect on your performance using the SLICE model and ask your supervisor to complete a case based discussion including ethical issues (table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of ethical considerations for safe sedation practice in endoscopy

| Conscience | Puts patient's safety at the centre of careRecognises that patients who have received conscious sedation need adult supervision for 12–24 h after the procedureOnly performs unsupervised endoscopy if competent to do so |

| Compliance | Complies with national and local policies for responsible patient escorts for sedated patients.Complies with Mental Capacity Act 2005 and principle of patient autonomy |

| Concurrence | Respects and acknowledges patient's wish for sedation when escort not availableRespects that some patients may wish to rebook rather than not be sedatedRespects cultural, religious and social values that may impact on patient choices |

| Conversation | Communicates effectively with patients regarding risks and benefits of sedation and risks of not having a responsible escortProvides alternatives to sedation using non-judgemental, neutral languageExplains consequences of having sedation without a suitable escort (eg, inpatient admission) |

| Conversion | Explains safe alternatives to sedation, for example, unsedated endoscopy or use of local anaesthetic, particularly when risks of sedation are higher (eg, neuromuscular disorders or advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)Effectively and sensitively stands by own moral and ethical standpoint on safe sedation levels while being respectful to others |

Conclusion

All practising gastroenterologists should engage in reflective learning including ethical aspects of their professional work. Using a simple framework presented here, role models for effective and ethical decision making should become the norm for modern gastroenterologists.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Sue Roff for her inspiration with this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: SW planned, designed, wrote the drafts and final versions of the paper and is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Axon A. Ethical considerations in gastroenterology and endoscopy. Dig Dis 2002;20:220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musick DW. Teaching medical ethics: a review of the literature from North American medical schools with emphasis on education. Med Healthc Philos 1999;2:239–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myser C, Kerridge IH, Mitchell KR. Teaching clinical ethics as a professional skill: bridging the gap between knowledge about ethics and its use in clinical practice. J Med Ethics 1995;21:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College Physicians. Ethics in Practice: background and recommendations for enhanced support. http://bookshop.rcplondon.ac.uk/contents/pub82-e6d08817-6875-4f28-aea3-6917b3f7af64.pdf (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Rosendaal G. Teaching ethics in Canadian gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 2004;18:291–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillon R. Medical ethics education. J Med Ethics 1987;13:115–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swenson SL, Rothstein JA. Navigating the wards. Teaching medical students to use their moral compasses. Acad Med 1996;71:591–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wear D. On white coats and professional development: the formal and the hidden curricula. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:734–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Specialty Training Curriculum for Gastroenterology August 2010. http://www.gmc-uk.org/Gastroenterology_curriculum_2010.pdf_32486121.pdf (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang A, Melzer E, Bar-Meir S, et al. Clinical and communication simulation workshop for fellows in gastroenterology: the trainees’ perspective. Harefuah 2006;145:798–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.General Medical Council. Ready for revalidation: Supporting information for appraisal and revalidation. http://www.gmc-uk.org/Supporting_information100212.pdf_47783371.pdf (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roff S. Transplantation ethics for the 21st century: structured learning in clinical ethics (SLICE) module for undergraduate medical students. Newcastle University MEDEV Newsletter 01.16 2008 http://www.medev.ac.uk/newsletter/article/218/ (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice: being honest and trustworthy. http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice/probity_honest_trustworthy.asp (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modelling—making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ 2008;336:718–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paice E, Heard S, Moss F. How important are role models in making good doctors? BMJ 2002;325:707–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston C. Does the statutory regulation of advance decision-making provide adequate respect for patient autonomy? Liverpool Law Rev 2005;26:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.UK Clinical Ethics Network. Clinical Ethics Committees. http://www.ukcen.net/index.php/committees/introduction (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watchtower. Jehovah's Witnesses and the Medical Profession Cooperate. http://www.watchtower.org/e/19931122/article_01.htm (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.General Medical Council. Personal beliefs and medical practice—guidance for doctors. http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/personal_beliefs.asp (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Launer J. Supervision skills for Clinical Teachers 3: Interventive interviewing. http://www.johnlauner.com/81.html (accessed Aug 2012).