Abstract

Introduction

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) Strategy document ‘Care of patients with Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders’ recommends that all acute hospitals should have arrangements for out-of-hours (OOH) endoscopy staffed with appropriately trained endoscopists. The UK national audit published in 2010 found that only 52% of hospitals across the UK had a formal consultant-led OOH endoscopy on-call rota. The University Hospitals of Leicester (UHL) established a consultant-led rota in 2006, which now provides 24/7 endoscopy cover. To define the workload of a newly established OOH service, we examined procedures performed since the introduction of an OOH service in 2006.

Methods

The audit period covered August–January (6 months) for each of five consecutive years. Data were gathered from formal endoscopy reports on Unisoft reporting tool and OOH record books. We examined indication for endoscopy, timing of procedure, findings at index endoscopy, intervention and immediate outcome.

Results

Across the three UHL sites, data on 982 patients were analysed. Eighty-one percent of procedures performed were gastroscopies. 63% of the procedures were performed for GI bleed indications. Over the five years, there was an overall increase in the number of procedures performed where no pathology was found. Immediate outcomes postendoscopy were good, with over 90% being returned to their base ward.

Conclusions

The experience at UHL appears to show a trend towards an increasing number of procedures performed OOH, with fewer positive findings and less need for therapy. A likely contributing factor is the ongoing shortage of medical beds, requiring more routine work to be done OOH in order to expedite discharges. However, early specialist endoscopic input is likely to improve patient management. The impact of an OOH service on other services, however, needs to be carefully considered.

Keywords: ENDOSCOPY, DUODENAL ULCER, GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING, OESOPHAGEAL VARICES

Introduction

The incidence of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is 50–150 cases per 100 000. It is associated with significant mortality, accounting for more than 4000 deaths per year in the UK.1 A review of data from the National Patient Safety Agency's National Reporting and Learning System identified 28 safety incidents between September 2004 and May 2008 in patients who arrived out of hours (OOH) as emergencies with UGIB. The lack of an on-call rota or service to enable a patient to receive emergency endoscopy treatment was highlighted as an issue. Nine of these emergencies resulted in deaths.2

The 2010 British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) UK National Audit on the use of endoscopy for the management of acute UGIB3 identified that in the group of hospitals that responded to the invitation, only 52% provided a formal OOH endoscopy service. In hospitals without an on-call rota, 13% of endoscopies were being conducted OOH; nevertheless, reliant on ‘ad-hoc’ or ‘goodwill’ arrangements. The risk-adjusted mortality was found to be approximately 20% higher in hospitals without an OOH service. There is also good evidence that emergency endoscopy reduces blood transfusion requirements, surgery rates and lengths of hospital stay.4–7

This paper looks at some aspects of the OOH endoscopy service at University Hospitals of Leicester (UHL) since full implementation of the service 5 years ago. Our paper adds to the considerations highlighted in the paper by Shokouhi et al8 looking at the setting up and running of a cross-country OOH GI bleed service. We focused on overall workload, indications, diagnoses, interventions and trends in referral and working patterns.

Historical background and development of the service

UHL National Health Service (NHS) trust comprises three hospital sites spread across the city of Leicester with a total catchment population of one million patients.9 There is a single large A&E department at the Leicester Royal Infirmary, one of the largest in the country with over 150 000 attendances a year,10 and a tertiary centre cardio-respiratory unit at Glenfield Hospital with a large coronary care and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) unit. The Leicester General Hospital offers a broad range of medical and surgical services. Services at this hospital, however, have undergone changes over the last 2–3 years with expansion of surgical and a dramatic reduction of medical inpatient services. The hospital continues to offer the full range of renal services.

Until 2005, UHL had no formal arrangements for the provision of OOH endoscopy. We define OOH as any endoscopy taking place outside of normal working hours (from Monday to Friday, 9:00 until 17:00 excluding bank holidays). The management of patients admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding was dependent on medical and surgical on-call personnel with variable levels of endoscopic expertise. There were also informal arrangements depending on the goodwill of off-duty consultant gastroenterologists and surgeons. Prior to the introduction of the OOH service, endoscopy usually took place in surgical theatres and relied on auxiliary staff who were often not properly trained in endoscopy, let alone advanced haemostatic techniques.

The necessity of providing a formal OOH endoscopy service was recognised both by the body of endoscopists and even more so by our medical and surgical colleagues who felt very vulnerable when managing these emergencies in an on-call setting. It was accepted that the quality of care for an OOH bleeder would depend on the availability of appropriately trained endoscopic personnel, both endoscopists and nurses.

The main difficulties as far as the introduction of the service was concerned related to the impact the withdrawal of gastroenterologists would have on the provision of acute medical cover. Likewise, compensatory rest periods both for gastroenterologists and nurses would leave gaps in the day-to-day routine provision of care.

Following a serious untoward incident, a weekend only rota covering all three-hospital sites was set up comprising a consultant gastroenterologist (1 in 10 rotas with prospective cover) and a single senior endoscopy nurse. It was soon recognised that the lack of cover over weekday nights was indefensible. Likewise, difficulties in accessing theatres overnight led to a rapid reorganisation within 6 months, helped by the appointment of several acute physicians.

The body of gastroenterologists withdrew from the medical rota over weekends and at night in exchange for a comprehensive OOH endoscopy service. All gastroenterologists continued to provide daytime cover for unselected medical emergencies on a weekly basis (1 in 13 weeks).

It was agreed to concentrate on GI bleeding and not to extend the service to the provision of an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (due to lack of consistent endoscopic expertise across the group of endoscopists). A referral protocol was introduced and developed as a variant of the Blatchford protocol. The rota was designed to minimise the impact on direct clinical care. If possible, the consultant covering the night would normally be scheduled for a supporting professional activity in the morning, allowing for some compensatory rest in the event of a late callout. The supporting team was increased to two trained nurses and one nurse auxiliary 8:00–20:00 on weekends and holidays, and two experienced endoscopy nurses overnight.

In addition to bleeder emergencies, non-bleeding patients admitted overnight would be accepted for upper and lower endoscopy on weekend endoscopy lists (9:00–1:00) to aid early management and to facilitate discharge planning for some patients. The bid for extra investment to cover additional nursing cost was pegged to a local capital bid to offer bowel cancer screening. All participating nurses had familiarised themselves over several months with the geography of all three sites, each of which has a dedicated two-room endoscopy unit. This was achieved by cross-site working arrangements within the trust.

The hub of the OOH service is based at the Leicester Royal Infirmary. It was agreed with the ambulance service to admit all patients with UGIB to the A&E department at this site. Unstable inpatient bleeders at the other two sites are endoscoped in their base hospitals. All endoscopy usually takes place in the endoscopy suite with the exception of critically ill-intubated bleeders (endoscoped in surgical theatres) and patients with bleeding emergencies on Intensive Therapy Unit (ITU), Coronary Care Unit (CCU) and in the ECMO unit. All endoscopies are logged via a central and shared reporting system (GI reporting tool-Unisoft medical systems). In addition, a separate book is kept by on-call nurses documenting any callout, and finally on-call activity is collated by one of our secretaries by means of sending activity spreadsheets to each consultant at the end of their on-call days.

The full service was formally launched in August 2006.

Methods

We analysed identical 6-month periods (August until January) for five subsequent years since commencement of the OOH service in 2006.

Endoscopy activity was captured via the shared GI reporting tool, the nurse callout documentation and the activity spreadsheets.

Patients included in the analysis were those endoscoped on weekends, bank holidays and overnight.

We examined timing of endoscopy, indications, endoscopic diagnoses, necessity for intervention, type of intervention and finally immediate outcomes postendoscopy. Basic statistical techniques using Fisher’s exact test were used to draw comparisons between various aspects of the data.

The criteria used to assess whether an OOH endoscopy was performed for a GI bleed indication or another indication are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Indications for out-of-hours endoscopy classified as ‘GI bleed’ versus ‘other indications’

| GI bleed indications | Other indications |

|---|---|

| Haematemesis | Dysphagia |

| Haematemesis+melaena | Nausea+vomiting |

| Melaena | Weight loss |

| Liver disease+evidence of bleed | Diarrhoea |

| Liver disease+drop in haemoglobin | Anaemia |

| Dysphagia+haematemesis | Abdominal pain |

| Intermittent rectal bleeding | Constipation |

| Overt rectal bleeding | Previous peptic ulcer |

| IBD assessment |

GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Results

A total of 982 endoscopic procedures were carried out. This is likely to represent 50% of the total number of OOH endoscopies performed over the total 5-year period. Figure 1 summarises the number of procedures for each of the 6-month audit periods. The types of endoscopic procedures are summarised in figure 2.

Figure 1.

Total number of all out-of-hours endoscopic procedures for each of the audited 6-month period.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of endoscopic procedures for each 6-month period. Asterisks indicate percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) insertion/PEG removal.

Table 2 illustrates the indications for endoscopy as documented in the endoscopy records and medical notes.

Table 2.

Procedures performed as per documented indication in endoscopy report

| Indication | 2006–2007 | 2007–2008 | 2008–2009 | 2009–2010 | 2010–2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haematemesis | 66 | 74 | 24 | 37 | 24 |

| Melaena | 17 | 30 | 35 | 22 | 43 |

| Haematemesis +melaena | – | 10 | 20 | 17 | 15 |

| CLD? varices | 7 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 15 |

| Anaemia | 13 | 31 | 24 | 20 | 27 |

| Rectal bleed | 7 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 14 |

| Diarrhoea | 8 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Dyspepsia | 7 | 9 | 14 | 8 | 6 |

| Dysphagia | 9 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 11 |

| Other | 2 | 5 | 20 | 22 | 30 |

| Not documented | 2 | 10 | 44 | 14 | 23 |

CLD, chronic liver disease.

The indications for 818 procedures were clearly documented. The remaining either had no indication documented on the endoscopy report, or fell outside our proposed indications for an emergency endoscopy (eg, nausea and vomiting, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) removal, abnormality on radiological investigation or foreign body removal). This does not necessarily imply an inappropriate procedure as the endoscopy may have been helpful in the acute management of inpatients.

Figure 3 demonstrates the timing of procedures. Compared with 2006–2007 when less than 1% of the procedures were performed at night (ie, on weekdays and weekend evenings and nights) in the 2010–2011 samples, approximately 8% of procedures were performed during these time periods.

Figure 3.

Timing of out-of-hours endoscopies. Procedures performed after 2:00 on weekends covered in ‘Wkend 17:00–21:00’ group.

Table 3 illustrates this further in terms of performance of OOH endoscopy for GI bleed indications versus ‘Other’ indications. The general trend from 2006–2007 to 2010–2011 appears to have been an increase in the number of referrals for OOH endoscopy for non-bleeding patients.

Table 3.

Performance of out-of-hours endoscopy for GI bleed indications versus ‘Other’ indications

| Year | GI bleed indications | Other indications | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2007 | 97 | 33 | 130 |

| 2007–2008 | 138 | 78 | 216 |

| 2008–2009 | 152 | 74 | 226 |

| 2009–2010 | 104 | 84 | 188 |

| 2010–2011 | 124 | 98 | 222 |

GI, gastrointestinal.

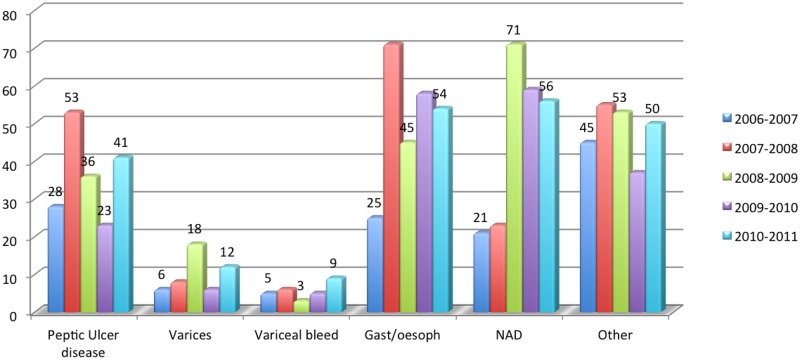

Figure 4 shows a breakdown of endoscopic diagnoses. Interestingly, the number of endoscopies performed where the findings were normal increased from 16% in 2006–2007 to 25% in 2010–2011, but this was not statistically significant (two-tailed Fisher's exact test p=0.0610). The number of patients with varices and those patients found to have peptic ulcer disease, as a proportion of all patients referred for OOH endoscopy, did not increase by statistically significant levels (two-tailed Fisher's exact test p=0.85 and p=0.74, respectively).

Figure 4.

Breakdown of endoscopic diagnoses for each of the audit periods. ‘Other’ findings include Barrett's oesophagus and upper gastrointestinal malignancy. NAD, nil abnormality detected.

Table 4 shows the proportion of procedures requiring endoscopic intervention, while figure 5 indicates the nature of endoscopic intervention. About 17% (167/982) of all OOH procedures required intervention.

Table 4.

Procedures requiring endoscopic intervention

| Year | Yes (%) | No |

|---|---|---|

| 2006–2007 | 30 (24.4) | 93 (75.6) |

| 2007–2008 | 40 (18.4) | 177 (81.6) |

| 2008–2009 | 31 (13.7) | 195 (86.3) |

| 2009–2010 | 38 (19.6) | 156 (80.4) |

| 2010–2011 | 28 (12.6) | 194 (87.4) |

Figure 5.

Nature of endoscopic intervention.

The main interventions were epinephrine injection and variceal banding. Smaller numbers of patients received combination therapy of endoclip with epinephrine injection, endoclip monotherapy and variceal banding in combination with sclerotherapy. Other therapeutic procedures included foreign body removal, polypectomy, argon plasma coagulation therapy and removal of PEG tube.

Immediate outcomes post-procedure are shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Immediate outcomes following endoscopy

| Year | To ward | Surgery/ITU/further endoscopy | Death |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2007 | 129 | 1 | 0 |

| 2007–2008 | 213 | 3 | 0 |

| 2008–2009 | 209 | 3 | 0 |

| 2009–2010 | 174 | 2 | 0 |

| 2010–2011 | 180 | 16 | 2 |

ITU, Intensive Therapy Unit.

This demonstrates that over 90% of patients were returned to the referring ward without the need for immediate escalation of treatment. The proportion of patients requiring escalation of treatment, for example, intensive care, interventional radiology or surgery was small (<1% of the total procedures in each year group). Two deaths were identified in the total cohort. Both patients presented with variceal bleeding, which could not be controlled endoscopically. In view of their comorbidity (advanced carcinoma in one and advanced alcoholic liver disease with end-stage hepatic failure in the other patient), they were not felt to be candidates for intensive care or emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement.

Table 6 illustrates a breakdown of the OOH endoscopies performed between 17:00 and 21:00 on weekday and weekends. During the audit periods, a total of 39 endoscopies were carried out during these times. Three patients required intensive care admission following endoscopy and one went on to have surgery for a bleeding duodenal ulcer.

Table 6.

Breakdown of endoscopic procedures performed at night

| Indication | Number of pts | Diagnosis | Therapy | Immediate outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLD?varices | 5 | Varices (n=1) Variceal bleed (n=4) |

Nil (n=1) Banding (n=4) |

To ward (n=4) ITU (n=1) |

| Ingestion of toxin/FB | 2 | Normal (n=2) | Nil (n=2) | To ward (n=2) |

| Haematemesis+melaena | 16 | Varices (n=4) Variceal bleed (n=4) Gastritis/oesophagitis (n=4) GU/DU (n=4) |

Banding (n=6) Nil (n=8) Epinephrine injection (n=2) |

To ward (n=15) ITU (n=1) |

| Haematemesis | 3 | DU (n=1) Varices (n = 1) Gastritis/oesophagitis (n=1) |

Epinephrine injection (n=1) Nil (n=2) |

To ward (n=2) Surgery (n=1) |

| Melaena | 12 | Variceal bleed (n=1) Normal (n=2) Duodenitis/gastritis (n=4) DU (n=4) Duodenal varices (n=1) |

Sclerotherapy/fibrin glue (n=1) Nil (n=7) Epinephrine (n=2) Adr/APC (n=1) Adr/APC/Clip (n=1) |

To ward (n=12) |

| Not documented | 1 | Bleeding DU (n=1) | Epinephrine injection (n=1) | ITU (n=1) |

Adr, Adrenaline; APC, Argon plasma coagulation; CLD, chronic liver disease; DU, duodenl ulcer; FB, foreign body; GU, gastric ulcer; ITU, Intensive Therapy Unit; NAD, nil abnormality detected; Px, patients.

Discussion

We believe our retrospective review to be one of the most comprehensive surveys done on the provision of an OOH endoscopy service within an urban setting in the UK.

The BSG nationwide audit of the management of upper GI bleeds3 showed that in the 52% of hospitals with a formal OOH rota or service with a consultant available on-call, endoscopy for acute UGIB was undertaken earlier and more frequently. This difference was not dramatic, as even in hospitals without a formal rota, OOH endoscopies were still being performed on an ‘ad-hoc’ basis, relying on consultant goodwill. Across the UK, there has not been a significant increase in the number of hospitals offering a formal rota, and earlier studies have demonstrated that in 2002 and 2005, 50% and 49% of hospitals, respectively, offered such a service,7 11 which remains deficient in 48% of hospitals.3

The risk-adjusted mortality in these hospitals was 20% higher than in hospitals with a formal rota.3 This sentiment is echoed in a retrospective case note review conducted in 2009,12 which demonstrated consistently low rebleeding and mortality rates in patients with UGIB presenting to a hospital with a dedicated bleeder unit.

The results of an electronic survey published in 2007 in Clinical Medicine found that in hospitals without an OOH rota, the main constraints included funding (58%), availability of endoscopists (57%), availability of nursing staff (41%) and Global Implicit Measure (workload) (39%).7

The recently published National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on ‘Acute UGIB: management’ recommend that units seeing more than 330 cases per year should offer daily endoscopy lists.13

The impact of an OOH endoscopy on mortality and rates of surgery, and questions regarding the timing of an emergency endoscopy are a matter of ongoing debate. The Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on non-variceal UGIB,14 drew on a systematic review of three randomised trials concluding that endoscopy within 12 h or earlier does not result in a better clinical outcome, improvement in mortality, reduction in surgical need or reduced requirement for blood transfusion. Furthermore, it was suggested that very early endoscopy might lead to increased use of endoscopic treatments, which may not be appropriate.

However, to counter this three American studies conducted in 2009 and 2010,15–17 indicated that patients presenting with UGIB over weekends have an increased mortality, which is likely to be related to longer waiting times for endoscopy.

Our audit has several strengths and weaknesses. It would have been interesting to compare mortality rates and lengths of stay with historical figures. Sketchy data collection and coding difficulties prior to the introduction of the OOH service, particularly in the case of patients who underwent laparotomy with and without a previous endoscopic attempt at haemostasis made a direct comparison of patient cohorts difficult.

The multidisciplinary nature of ad hoc arrangements without an agreed standardised way of capturing the details of patients presenting with acute GI bleeding added to these problems. In view of this, we were not able to produce historic meaningful data regarding 30-day mortality, an accepted BSG quality and safety standard.

It would have been desirable to look at the timing to endoscopy, that is, the proportion of patients presenting with acute UGIB who received endoscopy within 24 h; the patients initial presenting Rockall–Blatchford scores, transfusion requirements and long-term outcomes, focusing on mortality, re-bleed rates and progression to surgery. However, it was felt that this was beyond the scope of this review, which was mainly aimed at defining the workload of an OOH endoscopy service.

At first glance, the total number of true OOH endoscopies (ie, between 17:00 and 21:00) appears low, for example, 18 callouts over the six months of the last audit period. However, we would like to point out that endoscopy per se forms only part of the OOH service. Phone calls to discuss GI emergencies are common, and although we are not able to provide accurate data, our experience is that discussion between the on-call endoscopists and other resident on-call personnel take place approximately one in three nights.

Our audit highlights a number of interesting points. Demand for our service after the initial year has been consistently strong with little increase in referral numbers from year 2 onwards. We appear to be conducting an increasing number of procedures for what are potentially non-GI bleed indications (from 27% in 2006–2007 to 34% in 2010–2011) (p=0.0006). While this is likely to be multi-factorial, one likely contributing factor is the ongoing shortage of medical beds; a result of bed cuts in a time of an increasing number of emergency admissions. This has resulted in an increasing use of emergency services for ‘routine’ work in order to facilitate early discharges. However, weekend endoscopy for non-GI bleed indications might allow more timely diagnosis and management of patients presenting with other GI symptoms. Interestingly, the total number of endoscopies per 6-month period remained largely unchanged for 4 years running.

This is likely to be a reflection of changes in service provision throughout the normal working week and will be discussed in detail below.

The number of patients undergoing dual therapy for endoscopic haemostasis was disappointingly low. Only 7% of our interventions employed dual therapy in the form of endoclip with epinephrine injection. Our interventions fall short of NICE guidelines issued in June 2012,18 which states that epinephrine monotherapy should not be used for the management of non-variceal upper GI bleeding, and ideally first-line therapy should be mechanical therapy with or without epinephrine injection, thermal coagulation or fibrin with or without epinephrine injection. This issue has been raised at recent departmental meetings.

The introduction of an OOH service poses interesting challenges. Over the first 3 years, we observed a ‘spill over effect’ of ‘routine’ procedures into the weekend. Patients such as stable bleeders with low-risk scores who could not be accommodated on already fully booked endoscopy lists would be booked on weekend lists. In response, we introduced a daily inpatient only list at the Leicester Royal Infirmary, and of late, the number of ‘inpatient only’ lists has been increased to two on a Friday afternoon.

We also observed inappropriate early calls for GI bleeders who had not been adequately resuscitated. Likewise, colleagues quickly get used to the ready availability of emergency endoscopy, which reduces the referral threshold for patients who could be safely managed as outpatients. This places more demand on the weekday service and constitutes a potential loss of income for acute services. Reinforcement of the referral protocol and constant exchange with colleagues in the emergency department and acute medical and surgical wards have addressed some of these issues, which nevertheless remain a challenge.

Introduction of an OOH bleeder service in our hospital trust, which with regard to size and catchment population is larger than most hospitals in the UK, requires careful forward planning. The ramifications as far as staffing levels and service provision are concerned are substantial. The impact on other specialties, particularly the acute medical take is likely to be significant too. We would agree with the recommendations made in the BSG OOH gastroenterology position paper,19 that consultant gastroenterologists offering an acute bleeder service should withdraw from the acute OOH medical take as running both takes simultaneously can be too onerous. This obviously places an extra burden on other medical colleagues; but in our experience, this is a price our colleagues working in medical and surgical specialties are happy to pay as a patient presenting with an UGIB presents a very uncomfortable challenge without access to endoscopic support. The value of our OOH service is demonstrated by the fact that in the 5 years since commencement of the service, there have been no serious untoward incidents as far as timely endoscopy is concerned. Furthermore, while it is difficult to quantify the impact of a 24/7 OOH bleeder service as an early management aid, clinically, it undoubtedly adds value.

The future will bring further challenges. Possible further cuts in the number of acute medical beds and the changing epidemiology of chronic liver disease will increase the demand for the provision of OOH endoscopy, gastroenterology and hepatology services in general.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Barrie Rathbone (Consultant Gastroenterologist, Leicester Royal Infirmary) for his help with this article.

Footnotes

Contributors: RDR: designed data collection tool, collected data, conducted statistical analysis and drafted the paper. Primary author responsible for the overall content of the paper. PW: revised the drafted paper and involved in the concept of designing the papers subject.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rockall TR, Logan RF, Devlin HB, et al. Incidence and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Br Med J 1995;311:222–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scope for Improvement: A toolkit for a safer Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) service. http://aomrc.org.uk/projects/item/upper-gastrointestinal-bleeding-toolkit.html (accessed 16 Dec 2012).

- 3.Hearnshaw S, Logan RFA, Lowe D, et al. Use of endoscopy for management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: results of a nationwide audit. Gut 2010;59:1022–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Salena BJ, et al. Endoscopic therapy for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: a meta analysis. Gastroenterology 1992;102:139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolopoulou V, Katsakoulis E, Thomopoulos K, et al. Does haemostatic therapy improve the prognosis in upper gastrointestinal bleeding? Br J Clin Pract 1995;49:186–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JG, Turnipseed S, Romano PS, et al. Endoscopy based triage significantly reduces hospitalization rates and costs of treating upper GI bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointestinal Endosc 1999;50:755–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyawali P, Suri D, Barrison I, et al. A discussion of the British Society of Gastroenterology survey of emergency gastroenterology workload. Clinical Medicine 2007;7:585–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shokouhi BN, Khan M, Carter MJ, et al. The setting up and running of a cross-country out-of-hours gastrointestinal bleed service: a possible blueprint for the future. Frontline Gastroenterology 2012;0:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.http://www.leicestershospitals.nhs.uk/aboutus/ (accessed 16 Dec 2012).

- 10.http://www.leicestershospitals.nhs.uk/aboutus/departments-services/emergency-department/what-we-do/ (accessed 16 Apr 2013).

- 11.Douglass A, Bramble M, Barrison I. National Survey of emergency endoscopy units. Br Med J 2005;330:1000–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidhu R, Sakellariou P, McAlindon ME, et al. Dedicated bleed units: should they be advocated? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;21:861–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NICE Clinical guidelines CG141 Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: management. June 2012. http://publications.nice.org.uk/acute-upper-gastrointestinal-bleeding-management-cg141 (accessed 10 Jan 2013).

- 14.Sung JJY, Chan FK, Chen M, et al. Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut 2011;60:1170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorn SD, Shah ND, Berg BP, et al. Effect of weekend admission on gastrointestinal outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NICE guideline CG141: Acute upper GI bleeding: management. Issued: June 2012. guidance.nice.org.uk/cg141 (accessed 7 Apr 2013).

- 19.British Society of Gastroenterology: Out of hours gastroenterology—a position paper. http://www.bsg.org.uk/pdf_word_docs/out_of_hours_07.doc (accessed 18 Mar 2013).