Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of Dry Blood Spot testing (DBST) for hepatitis C within a geographical area.

Design

This is a prospective cohort study of all individuals living in Tayside who had received a hepatitis C virus (HCV) DBST between 2009 and 2011.

Results

During the study, 1123 DBSTs were carried out. 946 individuals had one test. 295 (31.2%) of these individuals were HCV antibody positive on their first test. Overall, 94.3% (902/956) individuals returned for the results of their test. During the course of the study 177 individuals were retested and 29 new cases of hepatitis C were detected. 249 individuals attended for further follow-up, and 164 (65.5%) were PCR positive. All 164 PCR-positive individuals were offered referral into specialist HCV services for further assessment. Data showed 62.5% were genotype 3, 65.1% had a low viral load (<600 000 iu/ml) and 77.5% had a Fibroscan score below 7 KPa. To date, 40 have commenced treatment and a further 16 are currently in the assessment period. Overall, we have retained in services or treated 63.6% (105/164) of patients who were initially referred and with effective support mechanisms in place we have achieved sustained viral response rates of 90%.

Conclusions

The study has shown that DBST is a complementary technique to conventional venepuncture for the diagnosis of HCV. The majority of patients have low viral loads and low fibrosis scores, so that while this group of patients may be difficult to reach and may be challenging to maintain in therapy, they are easier to cure.

Keywords: HEPATITIS C, ANTIVIRAL THERAPY

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major health burden which is predicted to increase significantly over the next 20 years.1 Chronic HCV infection affects 200 million people worldwide.2 The early diagnosis and treatment of HCV infection is the only way to prevent the epidemic consequences of HCV-related liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma.3 4 Within the UK, the main source of HCV is injecting drug use, however, diagnosing HCV in people who inject drugs (PWID) has often proved challenging. The difficulties include practicalities of achieving venous access, the skill sets of the workers who have most contact with those at highest risk of infection, and the institutionalised barriers of access to healthcare for many of the patient groups at highest risk. There is also the view that testing these groups is not cost effective on the grounds of the uptake of the test and perceived subsequent poor entry and adherence to treatment.

Prevalence rates among injecting drug users in the UK have been reported to vary from 28% to over 44%.5 6 Unfortunately, testing for hepatitis C and other blood borne viruses (BBV) is not routine practice within the majority of drug services. Lack of diagnosis will deny individuals access to specialist care and treatment. Identifying infection in the early stages will prevent future complications of liver disease and cancer, and will improve treatment outcomes.7 It also has the potential to result in behaviour change and motivate individuals to access drug treatment.

Targeted testing for HCV in drug users has been shown to be cost effective8 and acceptable, however, it can be difficult to carry out due to poor venous access. Dry blood spot testing (DBST) has recently become available and has been shown to be a reliable alternative to blood samples.9 It has proven to be a robust and easy method of determining HCV status and acceptable to drug injectors.10 With appropriate training it can be carried out by all staff working in drug services, and does not need to be restricted to the remit of medical or nursing staff.

This paper presents an evaluation of the introduction of HCV DBST into a geographical area. It describes the local hepatitis C cohort and evaluates the effectiveness and outcomes of testing. It aims to answer the question ‘Is it worthwhile testing for HCV infection in active drug users?’

Methods

Setting

This is a prospective cohort study of all individuals living in Tayside who had received a hepatitis C dry blood spot test between 2009 and 2011. The region of Tayside is situated in the east of Scotland and includes the cities of Dundee and Perth and several small towns and rural areas, covering more than 1000 square miles and the healthcare needs of approximately 400 000 people. All individuals who had received a dry blood spot test in Tayside were included in the study.

All data were captured using a hospital-based clinical database. For all individuals in the DBST cohort we collected data on demographic information, risk factors, laboratory tests, referral, follow-up and treatment. All patients in the study were allocated a code, and patient information used was anonymous.

Intervention

The development was carried out over a 28-month period between 2009 and 2011. Hepatitis C was tested for by taking a finger prick of blood, spotting this blood onto specially designed paper, and once dried, it was sent to Medical Microbiology where it is tested for HCV antibodies. Staff within local needle exchanges and drug services were given appropriate training, some members of the staff were drug support workers who did not have a nursing or medical background. They attended a 2 h interactive teaching session which covered issues related to BBV and the process of carrying out a dry blood spot test. They were all provided with written guidance and were supported in implementing this by a hepatitis nurse specialist. During the study, 120 staff across the region were provided with education to carry out the tests.

Testing for HCV was offered to all individuals who accessed needle exchange or drug treatment services. A follow-up appointment for results was arranged for 2 weeks after testing. All individuals who were tested were given appropriate harm reduction advice and were also offered referral to drug treatment services if they were not currently under care. All individuals who received a positive antibody HCV test were offered referral to the specialist hepatitis service. If the individual continued to be at risk of a BBV, retesting was offered on an annual basis.

Additional BBV testing on DBST has been validated for HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV). At the outset of the study, HIV testing was also included, and in the second year of the study, hepatitis B surface antigen testing was offered.

Follow-up

The results of intervention are presented as those patients who reached each follow-up stage by the end of the study period, this is a real-world observational study, staff and patients will have subsequent opportunities to progress results and consider therapy.

Results

During the study, 1123 DBSTs were carried out; 56.1% (631) of the tests were performed within needle exchange centres (NEXC), and 492 within drug treatment centres (DTC). DTCs included a range of services including assessment and maintenance prescription services, rehabilitation services and criminal justice services; 946 individuals had one test, 177 had a follow-up test greater than 1 year after the first. The demographics of the 946 individuals at the time of their first test are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of individuals receiving HCV DBST

| Demographic characteristics| | NEXC (n=525) | DTC (n=421) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range 16–57) | 30.1 years | 33.2 years | <0.001 |

| Male (%) | 330 (63) | 261 (62.3) | 0.787 |

| Ethnic group British Caucasian (%) | 518 (98.7) | 418 (99.3) | 0.525 |

| Current unemployment (%) | 520 (99.4) | 413 (98.2) | 0.265 |

| Risk factor injecting drug use (%) | 523 (99.6) | 421 (100) | 0.505 |

| Previous hepatitis C test (%) | 130 (24.7) | 30 (30.8) | 0.040 |

| Previous HIV test (%) | 127 (24.1) | 97 (23.1) | 0.780 |

| Previous B test (%) | 125 (23.9) | 95 (22.5) | 0.698 |

DBST, dry blood spot testing; DTC, Drug treatment centres; NEXC, needle exchange centres.

The risk factor for the majority of patients was injecting drug use. The drug used was predominantly heroin. There were two individuals tested who had injected steroids. There were two sex workers who accessed a test in NEXC as they were aware testing was been carried out there.

Data was collected on the number who had received a previous test for a BBV; 53 out of 946 (5.6%) had a hepatitis C test within the previous 12 months, and 264 out of 946 (27.9%) of the whole caseload had taken a test within the last 10 years. Table 1 lists the breakdown of previous BBV tests per group. The percentage of individuals having a previous hepatitis test was slightly higher if they had been accessing drug treatment services; however, the tests had not been carried out within drug services. Of the previous HCV tests, 35.8% were by general practitioners, 18.8% were carried out during an outpatient clinic or hospital admission, 11.9% of tests were taken in antenatal clinics, and 11.3% in prison.

Results of blood spot testing

Individuals numbering 295 (31.2%) were HCV antibody positive on their first test. The prevalence within the drug treatment group was higher at 35.3% as opposed to 27.5% in NEXCs (table 2); 214 were new diagnoses, and 81 were known to be HCV antibody positive in previous tests. None of the 81 retested were currently in follow-up with specialist hepatitis services. One individual who tested positive for HIV antibodies on follow-up bloods showed that he was HIV negative. There were 492 tests which were also tested for hepatitis B surface antigen, and there were no cases of HBV detected.

Table 2.

BBV test results at first DBST

| DBST BBV testing | All (n=946) | NEXC (n=525) | DTC (n=421) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All positive HCV test (%) | 295 (31.2) | 146 (27.5) | 149 (35.3) | 0.013 |

| Hepatitis C new diagnosis | 214 | 118 | 96 | 0.937 |

| Hepatitis C previous positive | 81 | 28 | 53 | <0.001 |

| HIV pos test | 1 | 1 | 0 | N/A |

| Hepatitis B pos test | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A |

BBV, blood borne virus; DBST, dry blood spot testing; DTC, Drug treatment centres; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; NEXC, needle exchange centres.

Overall, 94.3% (902/956) individuals returned for the results of their test. There was no difference in the small percentage who did not return for their results irrespective of site of testing. Of the 59 tests where results were not given, 44 were HCV antibody negative, eight were known to be HCV antibody positive, and seven were new diagnosis of HCV.

Repeat DBST for BBV

Individuals previously negative on testing, who continued high-risk behaviour, were offered a repeat test after 1 year. During the course of the study, 177 individuals were retested for all three BBVs; there were no new HIV or Hepatitis B infections, but 29 new cases of hepatitis C were detected, with 27 individuals who tested positive returning for their results. This gives an annual seroconversion rate for clients engaged in needle exchange and drug services of 16.1%, although nearly all the new positives were within the needle exchange setting.

Follow-up within specialist service

There were a total of 324 positive antibody tests. Results were issued to 307 and they were all offered referral to the specialist service for follow-up bloods to assess their PCR virus status. Nine declined the referral leaving 298 individuals who agreed to ongoing follow-up. The patients who declined referral were encouraged to seek drug treatment and given advice about prevention of transmission of hepatitis C. Forty-nine individuals failed to attend for follow-up for bloods and assessment, therefore, the PCR status by venous blood was unable to be documented on these individuals. Subsequent DBST PCR was able to been carried out on 32 of these individuals, and 10 were shown to be PCR negative.

Outcomes of follow-up

Individuals numbering 249 attended for further follow-up, and their PCR status was checked by venous bloods, and 164 (65.5%) were PCR positive; 85 individuals who were PCR negative were informed that they had cleared the virus, however, they were advised that this did not give them immunity from reinfection, and they were provided with harm reduction advice, and were encouraged to access drug treatment if not already on substitution therapy.

All 164 PCR positive individuals were offered referral into drug treatment and/or specialist HCV services for further assessment and treatment. Twenty-six declined further follow-up at this stage, and will be referred back to the specialist service by their key worker when appropriate.

Assessment and treatment

One hundred and thirty-eight individuals attended for further investigations. Bloods were obtained for genotyping and further HCV viral load. Seven were unable to be typed because the viral load was too low for processing. Of the 131 processed, 46 (35.1%) were genotype 1, and 82 (62.5%) were genotype 3. The viral load was checked and 90 (65.1%) individuals had a low HCV viral load (<600 000 iu/ml) (table 3); 52 attended for further assessment which included an assessment of fibrosis using a Fibroscan, (Echosens, France), and the results suggest that the majority of individuals had no obvious fibrosis or mild fibrosis. Only 12 individuals had a score between 7.1 and 12 KPa suggesting moderate fibrosis, and three were above 12 suggesting cirrhosis. Individuals who continued to attend for assessment and scans were offered access to HCV treatment.

Table 3.

Viral load, genotype and fibrosis status of HCV positive patients

| Total=131 | NEXC (n=73) | DTC (n=58) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1 (%) | 30 (41.1) | 16 (27.5) | 0.146 |

| Genotype 2 (%) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | NS |

| Genotype 3 (%) | 42 (57.3) | 40 (68.9) | 0.205 |

| Genotype mix 1/3 | 0 | 1 (1.7) | N/A |

| Total=138 | n=77 | n=61 | |

| HCV viral load <100 000 iu/ml (%) | 28 (36.3) | 20 (32.7) | 0.720 |

| HCV viral load 100 000–600 000 iu/ml (%) | 23 (29.8) | 18 (29.5) | NS |

| HCV >600 000 iu/ml (%) | 26 (33.7) | 23 (37.7) | 0.720 |

| Total=52 | n=23 | n=29 | |

| Fibroscan score <7 kpa (%) | 18 (78.2) | 19 (65.5) | 0.368 |

| Fibroscan score 7.1–12 kpa (%) | 4 (17.3) | 8 (27,5) | 0.513 |

| Fibroscan >12 kpa (%) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (7.7) | NS |

DTC, Drug treatment centres; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; NEXC, needle exchange centres.

Continuing follow-up in anti-HCV therapy service

In the follow-up period to date, 138 HCV PCR individuals accepted referral to specialist services: 40 had commenced treatment. The mean age of individuals starting treatment was 33.4 years, and 29 (72.5%) were male. They were all treatment naïve, and the majority received interferon and ribavirin therapy for 24–48 weeks dependent on genotype. Genotype 1 patients who had a viral load under 600 000 iu, and obtained a rapid viral response (HCV PCR negative at 4 weeks) were given 24 weeks treatment. At the end of the study, protease inhibitors were approved, and two genotype 1 patients in the cohort received this in addition to interferon and ribavirin.

Twenty-six had completed the full course of treatment, one was non-compliant and stopped, one was non-compliant and was a non-responder. Twelve were still currently on treatment. Six were within the 6-month period of stopping treatment and were awaiting sustained viral response (SVR) results. Overall, 90.9% (20 out of 22) have had a sustained response to treatment (table 4).

Table 4.

Demographics of 40 treatment patients

| Total=40 | NEXC (n=17) | DTC (n=23) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 15 (88.2) | 14 (60.8) | 0.078 |

| Mean age starting treatment | 33.2 years | 33.5 years | 0.876 |

| Genotype 1 (%) | 5 (29.4) | 5 (21.7) | 0.716 |

| Genotype 2/3 (%) | 12 (70.5) | 18 (78.2) | 0.716 |

| HCV viral load <600 000 (%) | 10 (58.8) | 10 (43.4) | 0.523 |

| Fibrosis score <7 (%) | 13 (76.4) | 14 (60.8) | 0.332 |

| Outcomes end treatment=28 | n=10 | n=18 | |

| Completed treatment | 10 | 16 | 0.520 |

| Incomplete treatment/relapse | 0 | 1 | N/A |

| Incomplete non-responder | 0 | 1 | N/A |

| SVR data=22 | n=10 | n=12 | |

| SVR | 10 | 10 | 0.480 |

| Relapses | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| Sustained viral response (ITT) (%) | 10/10 (100) | 10/12 (83.3) |

DTC, Drug treatment centres; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; ITT, intention to treat; NEXC, needle exchange centres; SVR, sustained viral response.

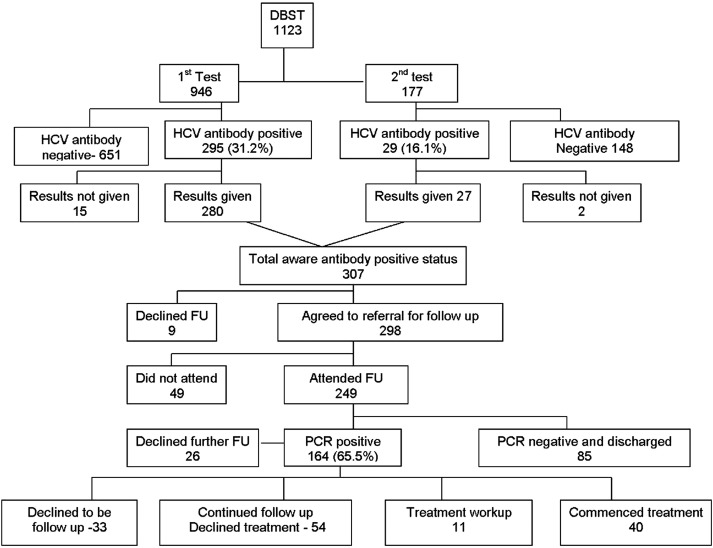

A further 16 were currently in the assessment period for treatment; 54 were in continued follow-up and working towards treatment, the delay in treatment being due to ongoing problems with drug misuse. The priority for these individuals was to be stabilised on drug treatment and, if needed, address other health or social issues before they wished to start HCV therapy. Thirty-eight individuals had declined further follow-up, and three individuals died from a drugs-related death (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hepatitis C dry blood spot testing outcomes.

No follow-up in HCV specialist service

At the end of the study period, there were a total of 101 patients who had not continued with follow-up. Ten had been shown to be PCR negative on DBST and did not require further follow-up. Seventeen had not received their results; 35 were not aware of their PCR status, and 39 had declined further follow-up. Of these 101, seven were dead, four were in prison outwith the region, two had moved from the area, 56 were in current contact with local drug services. Thirty-one were not known to be in contact with drug or other community services. Forty-four of these individuals were tested in the NEXC. Although they had not attended for follow-up in HCV specialist service, 32 had accessed drug treatment services after their diagnosis, and 27 were still on a methadone programme.

Cost analysis

To cost the intervention, the following assumptions have been made: first, that the cost of conventional HCV testing by venepuncture prelaboratory is essentially zero, justified by the fact that there would be no cost saving if HCV testing was stopped, as training for venepuncture would still be required and needles and syringes would still be used. Second, the laboratory cost of the HCV testing (£2.75) is the same between conventional testing and DBST except for an additional elution step for DBST and the provision of the DBST card and lancet which is an extra £5.40 per test. We did not quantify the cost of staff training, as this was predominately included in our BBV network training sessions which we had already secured funding for.

The total number of conventional HCV antibody tests performed during the study period was19 600. The number positive was 506 which is a prevalence of 2.6%. This indicates that the cost of a positive venous blood test is £106.52 as opposed to £29.81 for a positive dry blood spot test (table 5).

Table 5.

Cost of DBST (excluding staff time and VAT)

| DBST | Venous blood test | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per test (£) | 8.15 | 2.75 |

| Number tests | 1123 | 19600 |

| Number positive tests | 307 | 506 |

| Prevalence (%) | 27.3 | 2.6 |

| Total costs of tests over study period (£) | 9152.45 | 53900 |

| Cost per positive test (£) | 29.81 | 106.52 |

DBST, dry blood spot testing.

Discussion

This paper shows that DBST for BBV is easy to use and acceptable to both staff and clients. With effective training and clearly written staff information, this can be carried out by drug workers and social care staff, provided that there is a robust referral pathway or managed care network to ensure the transition of patients into treatment if they wish it. Staff within needle exchange reported that the uptake was good and the majority of clients who attended regularly took the test. Unfortunately, this cannot be quantified because clients attending needle exchange are not required to give identifying information.

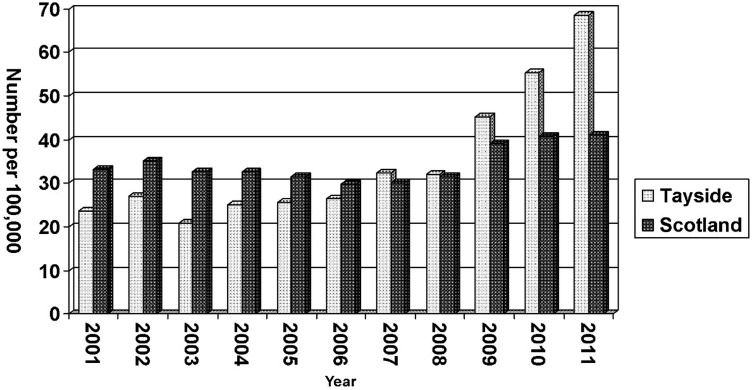

The study has significantly contributed to an increase in the number of new hepatitis C cases within our region. In 2008, there were 127 (rate of 32.1 per100 000) reported to Health Protection Scotland (HPS).11 In 2009, 2010 and –2011, this increased to 179, 233 and 276 respectively. At the end of 2011, the rate of new diagnosis had significantly increased to 68.5 per 100 000 of the Tayside population12 which is significantly higher than the overall rate for Scotland (figure 2). It is recognised that this increase is not just related to DBST testing as our local BBV Managed Care Network has been raising awareness of hepatitis C to healthcare professionals and social care staff with a series of teaching sessions and staff information material. However, while the number of new diagnosis of HCV due to conventional testing increased slightly during the time of the study, the increase of new diagnosis rate was predominately due to the addition of DBST.

Figure 2.

Persons reported to be HCV antibody positive. Rate per 100 000.

The introduction of DBST has provided drug users with access to BBV testing, and many would not have accessed testing in other settings. The results showed that over 70% had never received a test despite a known history of injecting drug use. Over 50% of the previous hepatitis tests were carried out in an opportunistic manner if individuals happened to be admitted to hospital, seen in a clinic setting or prison. Although there were a number of individuals who had previously tested hepatitis C positive, the use of DBST was a mechanism to encourage these individuals to address their health and hepatitis status and encourage them to access care and treatment. Although it was not part of the initial dataset, anecdotally, staff carrying out the test reported that in the majority of cases, where testing was repeated, this was because the individual had not previously been given the diagnosis or had been unclear of the result. In some cases, previous HCV PCR results had not been checked, and follow-up blood tests showed that they had cleared the virus.

At the beginning of the study, we were aware that offering testing to chaotic PWID would only be deemed effective if the result could be returned to the patient and lead to a number entering HCV therapy. During the study, after over a thousand tests, there were only 17 individuals who were newly diagnosed and not aware of their diagnosis. The use of DBST has encouraged individuals to engage with services. The study showed that a high percentage attended for follow-up bloods and assessment, and many have either started treatment or are in the process of assessment. It is expected that the number on treatment will continue to rise over time. This initiative is still in its early stages and, in some cases, it takes time for individuals to access drug care and treatment and to be in the best position to undertake HCV treatment. The attendance at follow-up appointments for Fibroscan is not optimal. This is probably due to the fact that our Fibroscan is situated with the main hospital centre. For some individuals this can mean a round trip of over 60 miles. All other care and treatment is provided locally in outreach services. We have now purchased a portable Fibroscan machine which can be taken to outreach clinics, and this should increase our attendance rates.

A question could be raised about the number of individuals who did not receive their initial results, or did not return for follow-up PCR bloods tests. The results of the study could be improved by the use of point-of-care testing,13 or issuing results of the initial dry blood test PCR result. As a team we did not believe that this would be in the best interests of the individual. The impact of a diagnosis of hepatitis C cannot be underestimated even in a group who may have considered themselves to be at high risk. This system allows individuals to come to terms with the diagnosis. They are informed that the test has been reactive for hepatitis C antibodies, and follow-up tests will reveal if they have cleared the virus spontaneously. In response to our early results, we now tell them that they have a one-in-three chance of spontaneously clearing the virus. This three-step approach helps to prepare individuals for a positive diagnosis and allows a member of the specialist hepatitis team to be involved in breaking the bad news.

The real benefit of routine testing is the ability to diagnose individuals early and provide anti-HCV treatment when it has the greatest chance of cure. The follow-up bloods and investigations suggest that the majority of individuals have low viral loads and low levels of fibrosis which are associated with high SVR rates. Our team have previously shown that providing treatment to active drug users and those on opiate substitution therapy can have similar rates of SVR rates to non-drug users.14

The study also shows a very high uptake of testing, and delivery of results in PWID is achievable by embedding testing in core drug misuse services, creating ‘a one-stop shop’. It has also demonstrated that this can, in turn, lead to a substantial number of patients entering therapy. The project was also unlikely to be as successful without the impact of our local BBV Managed Care Network which was established in 2004, which we have previously shown had a radical effect on improving access to care and treatment for a traditionally hard-to-reach population.15 This network crosses the boundaries of primary and secondary care and provides a communication link for all healthcare professionals looking after patients with hepatitis C in our region. Drug workers are able to refer to the specialist service, and patients are seen in outreach clinics throughout the region.

The study did not monitor if the diagnosis of hepatitis C had any effect on behaviour change. It would have been helpful to examine other effects of both a positive and negative diagnosis. Anecdotally, staff within the needle exchange believe that an important outcome of the project is that a diagnosis of hepatitis C testing appears to encourage individuals to access drug treatment. Although it is recognised that there are a number of other factors that could have influenced this, there were a significant number who accessed drug treatment after their positive test. In addition, staff within the drug services providing the test believe that some individuals appear to have had a positive experience of testing. Many drug users have a fatalistic approach to BBVs, and some assumed that they were positive when in fact their test was negative. This result seemed to have an impact in increasing their use of clean equipment, however, this may have been a short-term outcome. The study also raised concerns about the number of new positives diagnosed within the second year of the study, this is a high-risk group but, anecdotally, it has been reported that in some cases a negative test may have given them a false sense of security, making them invincible to infection. Future studies currently being designed will, hopefully, begin to tease out some of these issues.

Conclusion

It was widely believed that testing for HCV in PWID was pointless as it would not lead to new diagnosis of treatable patients. The study has shown DBST is a complementary technique to conventional venepuncture for the diagnosis of HCV. DBST can be used in environments unsuited to taking blood samples, and used by existing non-specialist hepatitis staff working in drug treatment services and needle exchange facilities. Additionally, we have shown that the client group offered testing had a high uptake rate, and over 94% of individuals returned for their results.

More importantly, we have observed a significant number of individuals of those found to be HCV PCR positive entering into and being maintained in anti-HCV treatment programmes. It is an interesting observation that these patients have low viral loads and low fibrosis scores, so that while this group of patients may be difficult to reach and may be challenging to maintain in therapy, they are easy to cure. Overall, we have retained in services or treated 63.6% (105/164) of patients who were initially referred (figure 1), and with effective support mechanisms in place we have achieved SVR rates of 90%.

The use of DBST in chaotic populations of PWID is cost effective compared with conventional testing both in terms of cost per diagnosis and cost per entry into treatment. The DBST will become a vital tool in controlling the HCV epidemic and preventing the rise in the tide of HCV-related liver disease.

What is already known on this subject.

The early diagnosis and treatment of HCV infection is the only way to prevent the epidemic consequences of HCV-related liver failure.

Within the UK, the main source of HCV infection is injecting drug use, however, diagnosing HCV in people who inject drugs (PWID) has often proved challenging.

Testing for hepatitis C and other blood borne viruses is not routine practice within the majority of drug services.

What are the new findings.

The study has shown dry blood spot testing (DBST) is a complementary technique to conventional venepuncture for the diagnosis of HCV.

It can be used by existing non-specialist hepatitis staff working in drug treatment services and needle exchange facilities.

This can lead to significant increase of the number of PWID diagnosed and treated.

Individuals have low viral loads and low fibrosis scores, so that while this group of patients may be difficult to reach and may be challenging to maintain in therapy they are easier to cure.

How might this impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future.

The DBST will become a vital tool in controlling the HCV epidemic and preventing the rise in the tide of HCV-related liver disease.

It will provide evidence to other health boards, that the use of DBST in chaotic populations of PWID is cost effective compared with conventional testing both in terms of cost per diagnosis and cost per entry into treatment.

Acknowledgments

Particular credit has to be given to the staff within Cair Scotland Dundee who carried out a large number of tests and provided positive feedback on the project.

Footnotes

Contributors: The coauthors BPS, PGM, ME, JFD all made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data and interpretation of data. The paper was drafted by the author and it was revised critically for intellectual content by all the coauthors. Final approval has been given by coauthors for this version to be published. JD is the guarantor and is responsible for the overall content.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study is based on anonymous audit data and does not involve any participation from patients. This audit project did not require to be submitted for ethical approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, et al. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology 2010;138:513–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009;29(Suppl 1):74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alter HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis 2000;20:17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camma C, Giunta M, Andreone P, et al. Interferon and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in viral cirrhosis: an evidence-based approach. J Hepatol 2001;34:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy KM, Hutchison SJ, Wadd S, et al. Hepatitis C virus among injecting drug users in Scotland: a review of prevalence and incidence data and the methods to generate them. Epidemiol Infect 2007;135:433–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balogun MA, Murphy N, Nunn S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis C in injecting drug users attending genitourinary medicine clinics. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:980–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis c: impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastoenterology 2006;131:979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castelnuovo E, Thompson-Coon J, Pitt M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of testing for hepatitis C in former injecting drug users. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:1–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuaillon E, Mondain AM, Meroueh F, et al. Dried blood spot for hepatitis C virus serology and molecular testing. Hepatology 2010;51:752–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craine N, Parry J, O'Toole J, et al. Improving blood-borne viral diagnosis; clinical audit of the uptake of dried blood spot testing offered by a substance misuse service. J Viral Hepat 2009;16:219–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Protection Scotland. HPS weekly report. Persons in Scotland reported to be hepatitis C antibody positive; number and rate/100000 population1 by NHS board and year of earliest positive specimen to 31 December 2008. Glasgow: HPS, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Protection Scotland. HPS weekly report. Persons in Scotland reported to be hepatitis C antibody positive; Number and rate/100000 population1 by NHS board and year of earliest positive specimen to 31 December 2011. Glasgow: HPS, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SR, Yearwood GD, Guillon GB, et al. Evaluation of a rapid point of care test device the diagnosis of hepatitis c infection. J Clin Virol 2010;48:15–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafferbhoy H, Miller MH, Dunbar JK, et al. Intravenous drug use: not a barrier to achieving a sustained Virological response in HCV infection. J Viral Hepat 2012;19:112–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tait JM, McIntyre PG, McLeod S, et al. The impact of a managed care network on attendance, follow-up and treatment at a hepatitis C specialist centre. J Viral Hepat 2009;17:698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]