Abstract

Options for the treatment of acute severe ulcerative colitis have broadened with the use of ciclosporin and infliximab, but corticosteroids remain first-line treatment. However, an optimum regimen for drug, dose and duration has not been established in the 57 years since Truelove and Witts first reported their value. In the absence of evidenced-based guidance this study sought to discover how gastroenterology units in the UK manage patients with acute severe colitis. In January 2010 a questionnaire was sent to all members of the inflammatory bowel disease section of the British Society of Gastroenterology enquiring about their use of corticosteroids in a typical patient with acute severe colitis. One hundred and two responses were obtained, representing more than 50% of the UK gastroenterology units. No consensus, and a wide variation in practice was found between these units. Over 70% of responders initially treat patients with intravenous hydrocortisone (400 mg/day), although some units prefer methylprednisolone and dexamethasone. On transfer to oral treatment, all units use prednisolone, most starting with 40 mg/day. There are no agreed national or international guidelines on the reducing regimen or duration of oral treatment—the area of greatest variation in our survey. Most units reduce prednisolone by 5 mg/week, but because of variations in the timing and magnitude of dose reduction, total exposure to prednisolone varies by 2.6-fold. To minimise harm from undertreatment or overtreatment of acute severe colitis a controlled study of prednisolone dose and duration is needed.

Keywords: CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE, CHRONIC ULCERATIVE COLITIS, CIRRHOSIS, CLINICAL DECISION MAKING, COLLAGENOUS COLITIS

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis is a complex disorder where the interplay between multiple environmental and genetic factors results in chronic disease, with diffuse mucosal inflammation, limited to the colon, causing recurrent symptoms and significant morbidity. Acute severe colitis is a potentially life-threatening gastroenterological emergency requiring prompt, effective management. Options for treatment have broadened with the recognition of the value of ciclosporin and infliximab, but corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for active disease. However, the adverse effects of corticosteroids are considerable, and affect cellular pathways in every organ. The commonest effects include cushingoid features, psychiatric disturbances, infections and metabolic disturbances. To minimise side effects and toxicity it is vital that the lowest effective dose of steroids is used, but despite a number of clinical trials in the 57 years since Truelove and Witts established the value of corticosteroids,1 an optimum regimen for drug, dose and duration has not been established. We therefore sought to discover how gastroenterology units in the UK were managing patients with acute severe colitis in the absence of evidenced-based guidance.

Methods

In January 2010, we sent a questionnaire to all members of the inflammatory bowel disease section of the British Society of Gastroenterology, enquiring about their use of corticosteroids in a typical patient with acute severe colitis, as defined by Truelove and Witts1 (table 1).

Table 1.

Truelove and Witts’ classification of severity of ulcerative colitis

| Activity | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of bloody stools per day | <4 | 4–6 | >6 |

| Temperature (°C) | Afebrile | Intermediate | >37.8 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | Normal | Intermediate | >90 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | >11 | 10.5–11 | <10.5 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | <20 | 20–30 | >30 |

We asked about the initial regimen of intravenous steroid, the starting dose of oral steroid when transferring from the intravenous route, the tapering schedule and total duration of treatment. Total steroid exposure was calculated from the dosing regimen.

Results

In the UK 174 Trusts/Health Boards are involved in the treatment of acute severe ulcerative colitis, and we obtained 102 responses from 94 hospitals within these organisations. Seventy-six per cent of respondents use a regimen of intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg, 6-hourly, as the initial treatment. Fifteen per cent of respondents use other doses of intravenous hydrocortisone, ranging from 50 mg 8-hourly to 200 mg 6-hourly. Intravenous methylprednisolone (from 30 mg to 80 mg daily) or dexamethasone (4 mg 6-hourly) is preferred by 9% (figure 1). When changing from intravenous to oral steroids, 88% of respondents begin prednisolone 40 mg daily. Potentially suboptimal dosing (prednisolone 30 mg daily) is used by 4% of respondents, while 6% use >40 mg/day. Only 2% of respondents use weight-adjusted dosing (1 mg/kg) (figure 2). No centre gives prednisolone in divided doses.

Figure 1.

Initial intravenous corticosteroid. H/C, hydrocortisone.

Figure 2.

Starting dose of oral prednisolone.

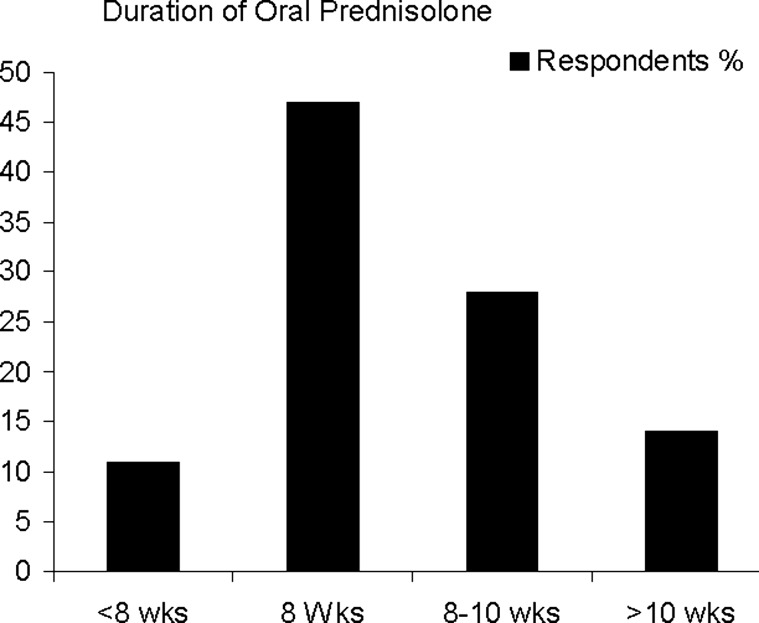

There is marked variation in the tapering schedule and in the total duration of oral steroid treatment. Forty-seven per cent of respondents prescribe oral steroids for 8 weeks, but 40% taper over a longer period (up to 12 weeks). The remaining 13% withdraw steroids in <8 weeks (figure 3). The commonest interval for dose reduction is 5 mg/week, but 28 different regimens were reported by the 102 respondents. From the data on dose and tapering schedules, we calculated the total dose of prednisolone given. The modal dose of prednisolone is 1.26 g. The lowest dose used is 0.75 g, and the highest is 2.14 g, resulting in a 2.6-fold difference in total exposure to prednisolone between the lowest and highest dosing schedules (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Duration of oral prednisolone.

Figure 4.

Total dose of oral prednisolone (g) used by each respondent.

Discussion

The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of ulcerative colitis is 243.4 per 100 000 individuals, or approximately 146 000 of the UK population.2 The clinical course is marked by exacerbation and remission, about 50% of patients relapsing in any year. Acute severe colitis is a potentially life-threatening complication,3 that demands clinical skills and experience to recognise it, institute appropriate treatment promptly and identify non-responders in order to consider other treatment options, including colectomy. As new drugs have become available, significant improvements in treatment have transformed the outlook for patients. In 1933 the reported mortality for patients with acute colitis was 75%.4 By 1950, this had fallen to 22%,5 while today, the UK national inflammatory bowel disease audit reports a nationwide mortality of 0.8%.6

Nearly 60 years after their introduction, steroids remain the first-line treatment, achieving remission in 40% of patients, and response in a further 30%, although 30% still require colectomy.7 Truelove and Witts were the first to undertake a randomised controlled trial of cortisone in patients with active colitis,1 demonstrating that an initial regimen of 100 mg/day, followed by tapering over 6 weeks, was an effective treatment, reducing mortality from 24% in the placebo group to 7% in the steroid-treated group. Similar efficacy was reported by Lennard-Jones et al.8 Different parenteral steroids have been used, most commonly hydrocortisone 200–400 mg/day, although methylprednisolone 40–60 mg/day is preferred by some units, owing to its lower mineralocorticoid activity, reducing the likelihood of oedema and hypertension. No study has compared these regimens, and nor has any study reported direct comparisons of different corticosteroids.9 Although continuous intravenous infusion of corticosteroid achieves a higher plasma concentration of drug than intermittent intravenous dosage, there is no additional benefit.9

The length of time that should be allowed for patients to respond to intravenous steroid therapy is contentious. In 1974, Truelove and Jewell recommended urgent operative treatment if there was no response to steroid therapy after 5 days,10 while those showing a response could be switched to oral prednisolone. In their study, 60% of patients were symptom-free at the end of day five, and 15% had a partial response. This 5-day rule has been widely adopted, but others have reported that steroids can be given safely for up to 10 days, allowing patients more time to respond.11 There is no proven benefit of extending treatment with intravenous steroid beyond 10 days.12

In our UK-based survey, most centres report using intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg 6-hourly as initial treatment. When the patient has responded, oral prednisolone is instituted and gradually tapered, but the doses used and the taper regimen vary greatly. The major risk of systemic steroids is their extensive adverse event profile, emphasising the importance of using steroids in the lowest effective dose. There are no agreed guidelines for the starting dose, reducing regimen and duration of oral treatment when changing from intravenous steroid, and few dose-ranging studies are available. Population-based observations indicate that prednisolone 40–60 mg/day or 1 mg/kg body weight per day achieves remission in about 50% of patients.12 Oral prednisolone is reported to show a dose–response effect between 20 mg and 60 mg/day: the 60 mg dose being most efficacious, but carrying a greater risk of corticosteroid-related toxicity.13

No randomised trials have studied steroid-tapering schedules. Most authorities recommend 40–60 mg/day until significant clinical improvement occurs, and then tapering the dose by 5–10 mg weekly until a daily dose of 20 mg is reached. At this point, tapering generally proceeds at 2.5–5 mg/week.14 Too rapid a reduction may be associated with early relapse, and <15 mg prednisolone daily is ineffective as a starting dose for active disease.3 Our survey shows that when changing to oral prednisolone most departments choose a starting dose of 40 mg. However, there is wide disagreement among centres on the duration of oral treatment, as well as tapering of the dose. We believe this variation in practice arises because of the absence of evidence to guide this aspect of the management of ulcerative colitis. Owing to the large differences between centres, the total dose of oral steroid for an individual patient varies greatly. The modal dose of prednisolone is 1.26 g, but some units use as little as 0.75 g, while others give >2 g.

In our survey, we asked respondents how they treat a patient with acute severe colitis in an idealised situation. The 2.6-fold variation in total dose of prednisolone shown by the survey suggests that some patients may be receiving inadequate doses, while others are being overdosed. Underdosage risks failure and unnecessary progression to surgery or more toxic rescue therapy, while overdosage increases side effects without conferring extra benefit. Deciding exactly what should be done, and when, remain domains where the doctor's judgement is of prime importance. Nevertheless, in this era of evidence-based medicine and nearly 60 years after the introduction of corticosteroid therapy, the time is now right for a formal controlled study to establish optimal steroid treatment regimens. Such a study might compare a fixed dose of hydrocortisone and initial dose of prednisolone with doses of each drug based on body weight and also compare tapering regimens, say of 5 mg decrements/week with 2.5 mg decrements. The results of such a study could be used in the future to avoid underdosage or overdosage of corticosteroids, with their consequences for patient management.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Dr Tim Orchard for distributing the questionnaire and to Elizabeth Manners for her valuable assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Contributors: SG conceived the idea. MI and SG devised the questionnaire and wrote the paper. MI analysed the data.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Brit Med J 1955;2:1041–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Kelly PJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology and management in an English general practice population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:1553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011;60:571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy TL, Bulmer E. Ulcerative colitis: a survey of 95 cases. Brit Med J 1933;ii:812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice-Oxley JM, Truelove S. Ulcerative colitis course and prognosis. Lancet 1950;255:663–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK IBD Audit 3rd round. Executive summary of the national results for the organisation of adult IBD Service in the UK. 2010. http://www.hqip.org.uk/national-inflammatory-bowel-disease-audit-many-hospitals-not-reaching-national-standards (accessed May 2012).

- 7.Jakobovits S, Travis SPL. The management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. Brit Med Bull 2006;75–76:131–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lennard-Jones JE, Longmore AJ, Newell AC, et al. An assessment of prednisone, salazopyrin, and topical hydrocortisone hemisuccinate used as out-patient treatment for ulcerative colitis. Gut 1960;1:217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodgson H. Systemic corticosteroid in IBD. In: Bayless TM, Hanauer SB. Advanced therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Vol. 1 IBD and ulcerative colitis. Shelton, Conn: People's Medical Publishing House, 2011:127–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truelove SC, Jewell DP. Intensive intravenous regimen for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Lancet 1974;1:1067–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JC, Cohen RD. Medical management of severe ulcerative colitis.Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2004;33:235–50, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2006;130:940–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron JH, Connell AM, Kanaghinis TG, et al. Out-patient treatment of ulcerative colitis. Comparison between three doses of oral prednisone. Brit Med J 1962;ii:441–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:501–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]