Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: AFP, AFP-L3, diagnostic value, hepatocellular carcinoma, PIVKA-II

Abstract

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), Lens culinaris-agglutinin-reactive fraction of AFP (AFP-L3), and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) are widely used as tumor markers for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This study compared the diagnostic values of AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II individually and in combination to find the best biomarker or biomarker panel.

Seventy-nine patients with newly diagnosed HCC and 77 non-HCC control patients with liver cirrhosis were enrolled. AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II were measured in the same serum samples using microchip capillary electrophoresis and a liquid-phase binding assay on an automatic analyzer. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analyses were also applied to all combinations of the markers.

When the 3 biomarkers were analyzed individually, AFP showed the largest area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) (0.751). For combinations of the biomarkers, the AUC was highest (0.765) for “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP > 10 ng/mL.” The combination of “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP > 10 ng/mL and AFP-L3 > 10%” had worse sensitivity and lower AUC (P = 0.001). The highest AUC of a single biomarker was highest for AFP and of a combination was “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP > 10 ng/mL,” with this also being the case when the cut-off value of AFP and AFP-L3 was changed.

Alpha-fetoprotein showed the best diagnostic performance as a single biomarker for HCC. The diagnostic value of AFP was improved by combining it with PIVKA-II, but adding AFP-L3 did not contribute to the ability to distinguish between HCC and non-HCC liver cirrhosis. These findings were not altered when the cut-off value of AFP and AFP-L3 was changed.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide,[1] and is highly prevalent in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, with incidence rates of 31.9/100,000 and 22.2/100,000, respectively, where the main risk factor is hepatitis B virus (HBV).[2] In Korea, HCC is the sixth most common newly diagnosed malignancy and the second most common cause of death among all malignancies.[3]

Several tools are available for detecting HCC. The recommended noninvasive methods include imaging techniques such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, and the use of tumor markers such as the level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP).[4,5] Many physicians use AFP in clinical practice to diagnose HCC.[6] However, AFP levels are normal in up to 40% of patients with HCC, particularly during the early stage of the disease, which reflects a low sensitivity.[7] To improve clinical outcomes for patients, more reliable serum biomarkers need to be identified. Another approach aimed at overcoming the limitations of AFP is to combine its measurement with that of a protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II).[8,9]

Protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II is an abnormal prothrombin protein that is present at higher levels in the serum of HCC patients. Since the first report by Liebman et al,[10] PIVKA-II has been identified as a highly specific marker for HCC and a predictor of the prognosis of HCC patients.[11,12] In numerous studies, it has been found that the combined measurement of PIVKA-II and AFP has a sensitivity ranging from 47.5% to 94.0%, and a specificity ranging from 53.3% to 98.5% in the early diagnosis of HCC, and these values are superior to those for either marker alone.[13–17] Also, Pote et al[18] showed that PIVKA-II could be useful for the diagnosis of early HCC and used as predictive marker of microvascular invasion.

In addition, 1 specific type of AFP—AFP-L3—binds to a lectin (Lens culinaris agglutinin) and displays serum levels that are in consistent with levels of AFP in human sera.[19] AFP-L3 reacts with L culinaris agglutinin A and it is a fucosylated variant of AFP. To differentiate an increase in AFP due to HCC or benign liver disease, AFP-L3 can be used.[20–22] It means that compared with the total AFP level, the AFP-L3 isoform seems to be more specific for diagnosing HCC.[23] A retrospective study conducted by Shiraki et al[24] found that 9 (41%) of 21 liver cancer patients showed high concentrations of AFP-L3 at 12 months before an imaging diagnosis, and that the ratio of AFP-L3 to total AFP was independent of the serum level of total AFP.[25] If the serum level of AFP-L3 is highly specific for HCC, it could be used to screen individuals at high risk of HCC and thereby facilitate its early diagnosis and the timely initiation of treatment.[26]

Many studies have compared the usefulness of tumor markers in diagnosing HCC, but direct comparisons of AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II, and their combinations in differentiating newly diagnosed HCC patients from liver cirrhosis (LC) patients have not been reported previously. We therefore investigated the diagnostic value of these biomarkers for detecting HCC. This was achieved by comparing the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and receiver-operating characteristics (ROCs) of the biomarkers both individually and in combination among newly diagnosed HCC patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

The subject cohort consisted of 298 HCC cases from the Digestive Disease Center at the Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, which were newly diagnosed between October 2013 and March 2016 by retrospective design. Among them, 79 HCC patients were selected for inclusion in this study after applying the following exclusion criteria: the baseline serum level of AFP, AFP-L3, or PIVKA-II was not obtained; presence of extrahepatic malignancy when HCC was diagnosed; previously treated for any type of malignancy before HCC was diagnosed; all other conditions with elevated AFP rather than liver disease; or fibrolamellar HCC which can show normal AFP. HCC was diagnosed based on histological findings or typical imaging characteristics as defined by the Korean Liver Cancer Study Group Guideline.[27] Also, we classified our patients by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification to characterize HCC of each patients.

A further 77 LC patients were selected in this study as a control group. LC was diagnosed based on a histological examination or clinical findings of portal hypertension.[13] The LC patients in the control group had undergone imaging studies to exclude HCC.

The institutional review board at Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital approved the study, and informed consent was not required for this analysis of retrospective data.

2.2. Measurement of AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II

Alpha-fetoprotein, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II were measured in the same serum samples using microchip capillary electrophoresis and a liquid-phase binding assay on an automatic analyzer (μTAS Wako i30, Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). The measurement range was 0.3 to 2000 ng/mL for AFP and 5 to 100,000 mAU/mL for PIVKA-II. AFP-L3 levels were calculated in sera whose AFP levels exceeded 0.3 ng/mL. If the AFP level of a sample was >2000 ng/mL or the PIVKA-II level was >100,000 mAU/mL, the original sample was manually diluted based on the previous results according to the manufacturer's instructions. All testing was conducted at the Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital by the same group of laboratory technicians, and none of the technicians was informed of the subject's status before testing.

We defined positivity for the 3 biomarkers alone as follows: AFP >10 ng/mL, PIVKA-II >40 mAU/mL, and AFP-L3 >10%. The cut-off value for serum AFP was 10 ng/mL since this is the setting used by our laboratory automatic analyzer (Wako i30). Because the cut-off value of other devices in our hospital is 20 ng/mL, we also determined whether the diagnostic performance of the biomarkers changed for a AFP cut-off value of 20 ng/mL, and we also analyzed the diagnostic performance of biomarkers for different cut-off values of AFP-L3 to verify the reproducibility of our study results.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 19.0.0 and Med-Calc version 16.4.3. To compare the diagnostic value of the tumor markers, ROC curves were plotted for each biomarker and for every combination of 2 or 3 markers. We classified the combinations into 2 types that are described as follows: the word “and” is used between biomarkers if all biomarkers in that combination were positive; and the word “or” is used if any biomarker in the combination was positive. For example, the combination “PIVKA-II or AFP or AFP-L3” means that at least 1 of the biomarkers is positive, whereas “PIVKA-II and AFP and AFP-L3” means that all of the biomarkers are positive. We used these methods to investigate the diagnostic value of each combination of biomarkers. Correlation analysis was used to identify relationships between the biomarkers.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics and biomarker levels

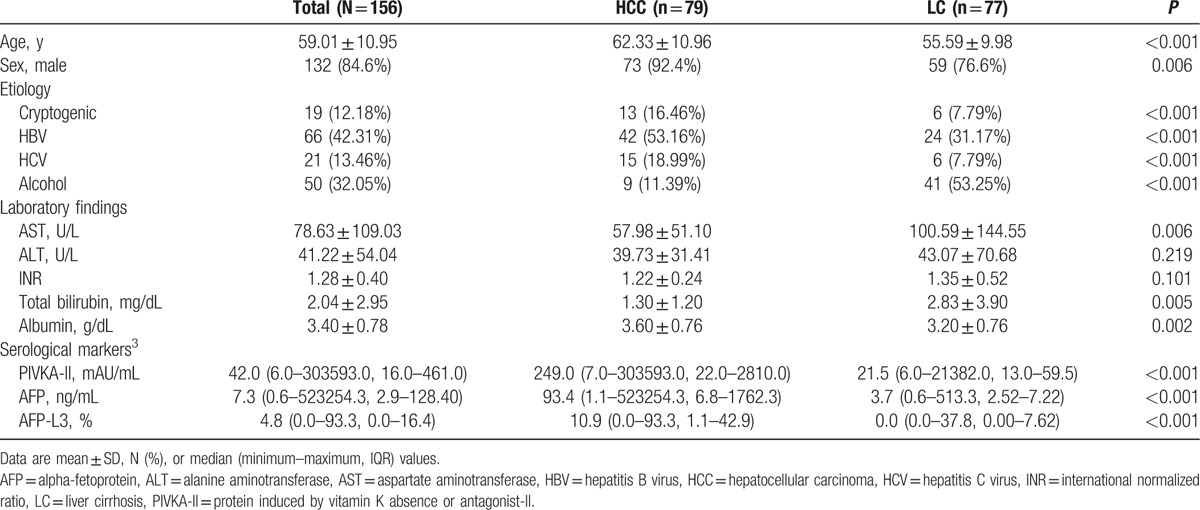

Among 156 patients (79 HCC and 77 LC), 66 patients (42.31%) were infected with HBV and 21 patients (13.46%) were infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Table 1). Infection with HBV or HCV was more frequent in the HCC group than in the LC group (P < 0.001). The most frequent cause of LC in the control group was alcohol (53.25%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

For liver enzymes, the serum level of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was higher in the LC group than in the HCC group (100.59 vs 57.98 U/L; P = 0.006). The serum level of total bilirubin was also higher in the LC group (2.83 vs 1.30 mg/dL; P = 0.005).

Because the serum levels of biomarkers are sometimes extremely high, we measured median and interquartile range (IQR) values to avoid these extreme outliers from producing misleading mean values, and thereby allow more accurate comparisons. The median levels of PIVKA-II, AFP, and AFP-L3 were significantly higher in the HCC group: 249.0 mAU/mL (IQR 22.0–2810.0 mAU/mL) in the HCC group and 21.5 mAU/mL (IQR 13.0–59.5 mAU/mL) in the LC group, 93.4 ng/mL (IQR 6.8–1762.3 ng/mL) in the HCC group and 3.70 ng/mL (IQR 2.52–7.22 ng/mL) in the LC group, and 10.9% (IQR 1.1%–42.9%) in the HCC group and 0.0% (IQR 0.0%–7.6% in the LC group (all P < 0.001), respectively.

Moreover, about BCLC staging of HCC patients, 16 patients (20.25%) were BCLC stage 0 and 40 patients (50.63%) were BCLC stage A (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2. Comparison of diagnostic values of biomarkers for differentiating HCC from LC

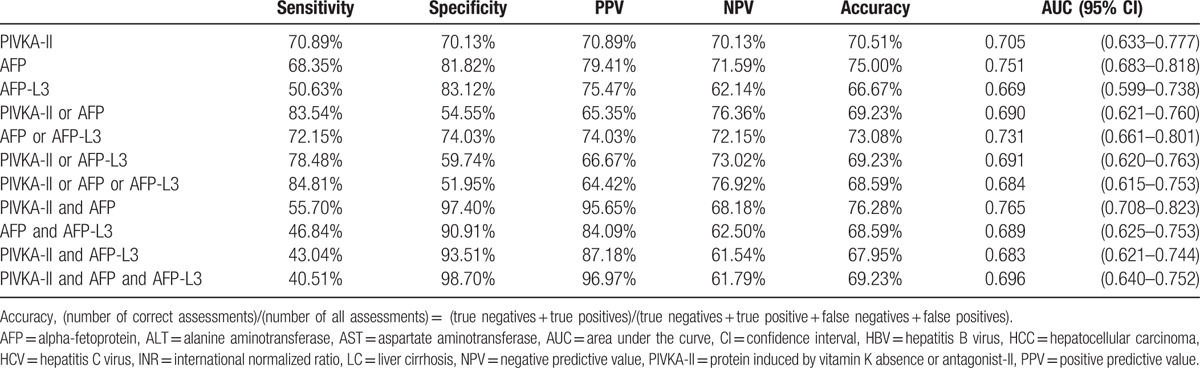

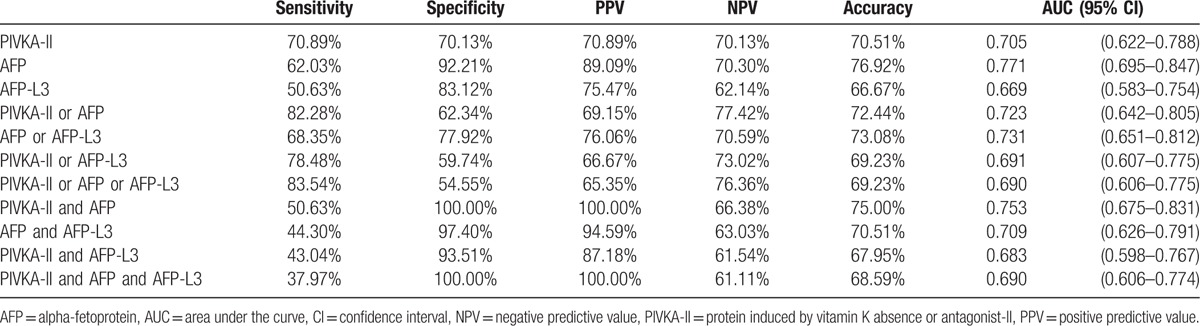

For the 3 biomarkers individually, AFP showed the highest area under the ROC curve (AUC) (0.751, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.683–0.818). The diagnostic performance (sensitivity/specificity/accuracy) of the biomarkers individually was 68.35%/81.82%/75.00% for AFP (AFP >10 ng/mL), 70.89%/70.13%/70.51%for PIVKA-II (PIVKA-II >40 mAU/mL), and 50.63%/83.12%/66.67% for AFP-L3 (AFP-L3 >10%) (Table 2). AUC did not differ significantly among the individual biomarkers (Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Diagnostic value of PIVKA-II, AFP, and AFP-L3 in discriminating HCC from LC.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of AUC values of the biomarkers. (A) AUC values of biomarkers individually (no significant differences). (B) AUC values of combinations using “or” (no significant differences). (C) AUC values of combinations using “and” (“AFP and PIVKA-II” vs “AFP and PIVKA-II and AFP-L3”; P = 0.001). AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, AUC = area under the curve, PIVKA-II = protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II.

For combinations of the biomarkers, the AUC was highest (0.765, 95% CI 0.708–0.823) for “PIVKA-II and AFP,” with a sensitivity and specificity of 55.70% and 97.40%, respectively (Table 2). The combination of “PIVKA-II and AFP” had a worse sensitivity (40.51%, P = 0.001) and lower AUC (0.696, P = 0.001) compared with “PIVKA-II and AFP and AFP-L3” (Fig. 1C).

The combination of “PIVKA-II or AFP or AFP-L3” showed the highest sensitivity of 84.81% and a specificity of 51.95%, and an AUC of 0.684, but did not differ significantly (P = 0.549) from the combination of “PIVKA-II or AFP” (sensitivity = 83.54%, specificity = 54.55%, and AUC = 0.690) (Table 2, Fig. 1B). These findings indicate that AFP-L3 did not improve the ability to differentiate between HCC and LC.

In case of patients classified by BCLC stage, the AUC was highest for AFP in each BCLC stage 0 (0.750, 95% CI 0.588–0.912) and BCLC stage A (0.863, 95% CI 0.777–0.948) (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). Both combination of “PIVKA-II or AFP or AFP-L3” and “PIVKA-II or AFP” showed the highest sensitivity, 68.75% in BCLC stage 0 and 87.50% in BCLC stage A each, and the sensitivity was same (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3).

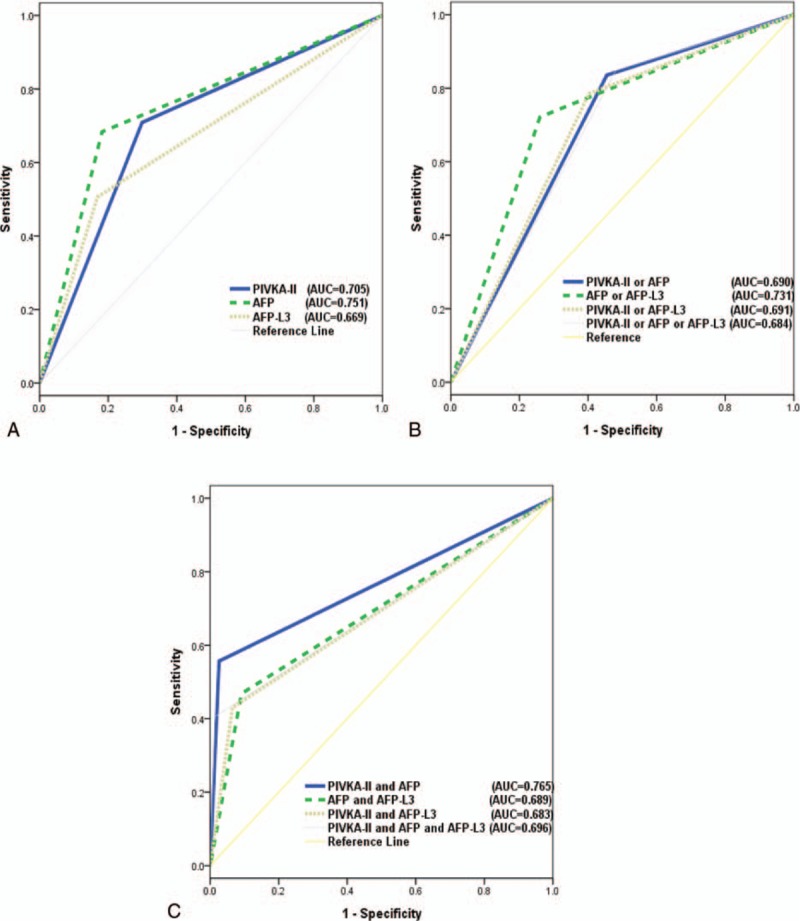

3.3. Correlation between biomarkers

Each biomarker has a different kind of serum level distribution and range. We analyzed the correlation coefficients to identify significant correlations between the biomarkers. Figure 2 shows the correlations among the serum levels of the markers. The coefficient for the correlation between PIVKA-II and AFP was 0.422, whereas that for PIVKA-II and AFP-L3 was 0.432 (both P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The correlation was strongest between AFP and AFP-L3, with a coefficient of 0.735.

Figure 2.

The correlation between serum levels of each biomarker. (A) AFP and AFP-L3 (r = 0.735, P < 0.001). (B) PIVKA-II and AFP (r = 0.422, P < 0.001). (C) PIVKA-II and AFP-L3 (r = 0.432, P < 0.001). AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, PIVKA-II = protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II.

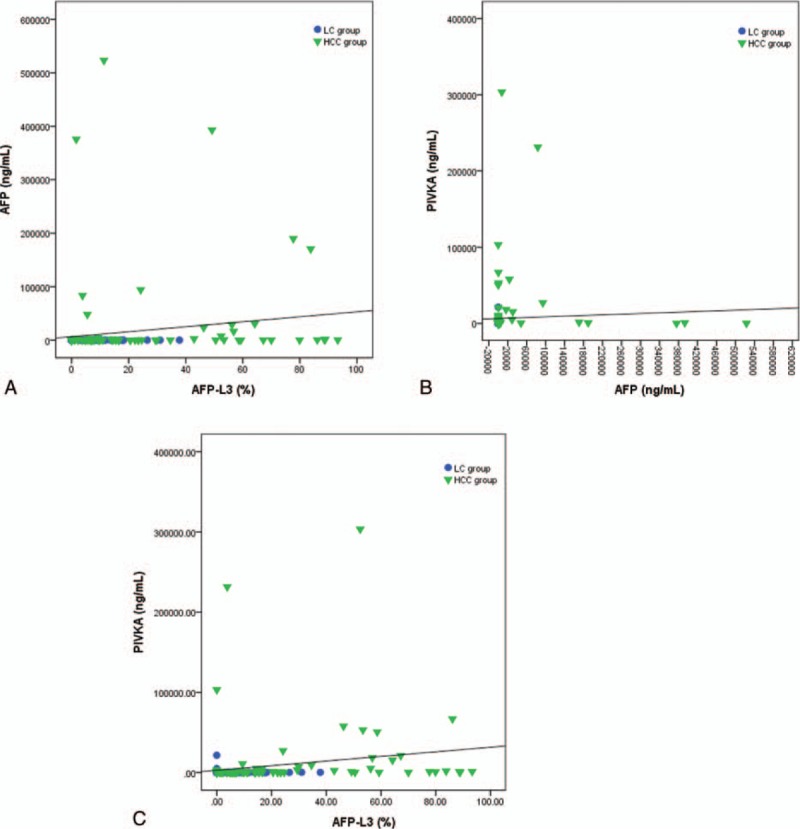

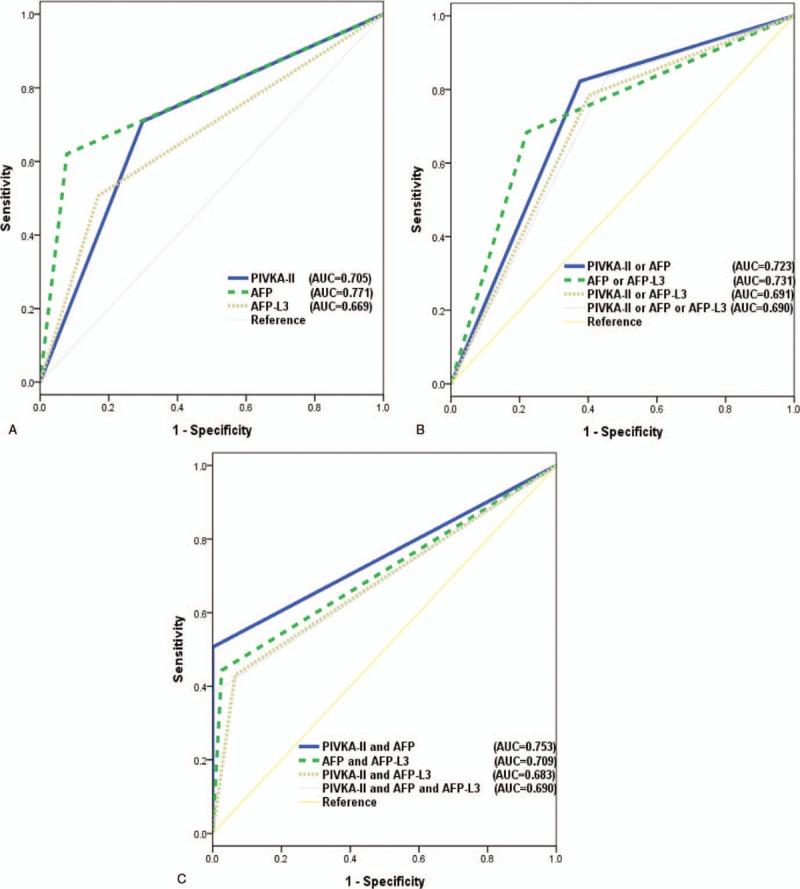

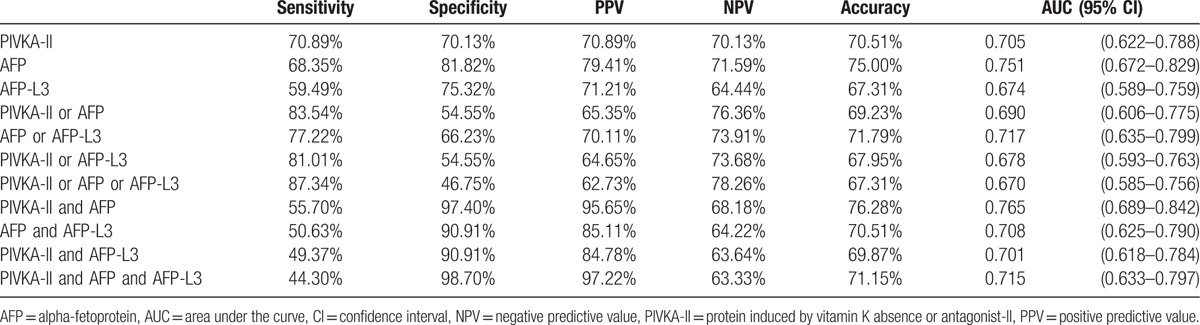

3.4. Changes in diagnostic value of biomarkers according to cut-off value

Changing the cut-off value of AFP from 10 to 20 ng/mL changed the diagnostic performance of the biomarkers. For individual biomarkers, the highest AUC was 0.771 for AFP >20 ng/mL (95% CI 0.695–0.847) (Table 3), which was significantly higher than the AUC for AFP-L3 (0.669, P = 0.005) (Fig. 3). Among the “or” combinations, that of “AFP or AFP-L3” showed the highest AUC (0.731, 95% CI 0.651–0.812), and there were no significant differences between the other “or” combinations. Among the “and” combinations, “PIVKA-II and AFP” still showed the highest AUC (0.753, 95% CI 0.675–0.831), being significantly higher than that for “PIVKA-II and AFP-L3” (0.683, P = 0.010) and “PIVKA-II and AFP and AFP-L3” (0.690, P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of biomarkers after increasing the cut-off value of AFP to 20 ng/mL.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of AUC values of the biomarkers for an AFP cut-off of 20 ng/mL. (A) AUC values of biomarkers individually (AFP vs AFP-L3; P = 0.005). (B) AUC values of combinations using “or” (no significant differences). (C) AUC values of combinations using “and” (“PIVKA-II and AFP” vs “PIVKA-II and AFP-L3”; P = 0.010; “PIVKA-II and AFP” vs “PIVKA-II and AFP and AFP-L3”; P < 0.001). AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, AUC = area under the curve, PIVKA-II = protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II.

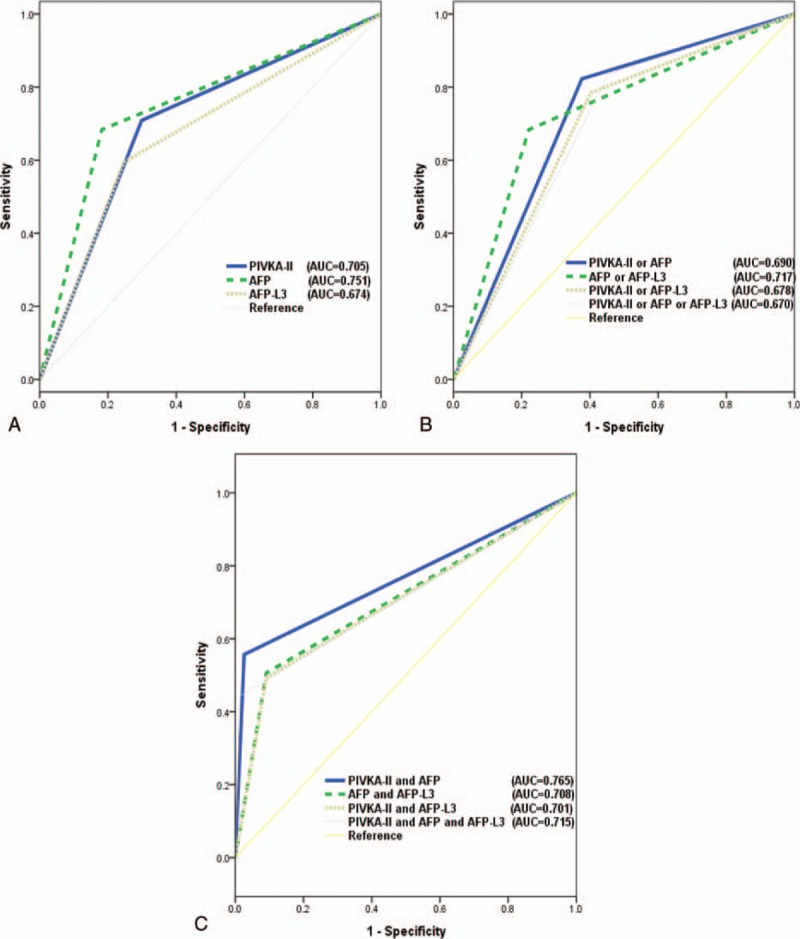

Changing the cut-off value of AFP-L3 from 10% to 7% also changed the diagnostic performance of the biomarkers. Among all the combinations, “PIVKA-II and AFP” showed the highest AUC (0.765, 95% CI 0.689–0.842), being significantly higher than that for “PIVKA-II and AFP and AFP-L3” (0.715, P = 0.001) (Table 4, Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Diagnostic performance of biomarkers after decreasing the cut-off value of AFP-L3 to 7%.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of AUC values of the biomarkers for an AFP-L3 cut-off of 7%. (A) AUC values of biomarkers individually (no significant differences). (B) AUC values of combinations using “or” (no significant differences). (C) AUC values of combinations using “and” (“PIVKA-II and AFP” vs “PIVKA-II and AFP and AFP-L3”; P = 0.008). AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, AUC = area under the curve, PIVKA-II = protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II.

4. Discussion

The early diagnosis of HCC is essential to ensuring that curative interventions can be implemented to improve the prognosis and long-term survival of patients.[28,29] For this reason, we performed a case-control study aimed at identifying valuable diagnostic tools other than imaging methods.

Chronic hepatitis B and C are thought to be the main causes of cirrhosis and HCC,[30] and HCC is mainly caused by infection with HBV in Asia. In Western countries, however, it is characteristically caused by infection with HCV.[31] In our study, chronic hepatitis (especially HBV infection) was the most common cause in the HCC group, whereas alcoholic LC was the most common cause in the control group. The results from our study are therefore likely to be representative of the total Asian population. Furthermore, this etiologic difference was discussed by previous study. Giannini et al[32] studied about determinants of elevated AFP in HCC patients. This study showed that viral etiology was independently associated with elevated AFP in HCC patients. Hence, the different etiologies between HCC patients and control patients in our study might be caused by characteristic of HCC.

Since HCC is 1 of the main causes of death in patients with LC[30] and most HCC patients have underlying LC, we decided to include LC patients without HCC as a control group. We examined the usefulness of AFP as a biomarker for detecting HCC based on previous studies demonstrating that elevated levels of AFP in LC patients is a risk factor for the development of HCC.[33,34]

Previous studies have shown that PIVKA-II could be helpful for the early diagnosis of small HCC tumors.[35,36] Moreover, several studies have shown that utilizing AFP-L3 could improve the detection rate of HCC when it is combined with PIVKA-II.[14,15,37,38] In addition, Lim et al[39] showed that combining AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II improved the diagnostic accuracy for HCC among cirrhotic patients compared with using each marker individually. In Japan, AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II are covered by Japan's national health insurance as serological biomarkers in clinical settings, and these tests are routinely used to screen for HCC.[40] According to the Japan Society of Hepatology Guidelines, which are the first evidence-base d clinical practice guidelines for HCC in Japan, AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II should be measured at intervals of 3 to 4 months in the very-high-risk group (patients with HBV or HCV-related LC) and at 6-month intervals in the high-risk group (patients with HBV or HCV-related chronic liver disease or LC due to other causes).[41,42]

However, we found that the combination of PIVKA-II and AFP was the most valuable panel for detecting HCC. We performed direct comparisons of the usefulness of AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II both individually and in combination in diagnosing HCC, and found that AFP was the best individual marker for differentiating between HCC and LC (sensitivity 68.35%, specificity 81.82%, AUC 0.751, 95% CI 0.683–0.818). Among all combinations of biomarkers, the combination of “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP > 10 ng/mL” had the highest AUC (0.765, 95% CI 0.708–0.823), with a sensitivity of 55.70% and a specificity of 97.40%. Other combinations of 2 or 3 markers did not provide superior diagnostic ability.

We also analyzed the diagnostic performance of biomarkers for different cut-off values of AFP to verify the reproducibility of our study results. The AUC of a single biomarker remained highest for AFP (AUC 0.771, 95% CI 0.695–0.847), and of a combination of biomarkers, it was highest for “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP > 10 ng/mL” (AUC 0.753, 95% CI 0.675–0.831), including after adjusting the cut-off value of AFP from 10 to 20 ng/mL. Furthermore, the AUC was significantly higher for AFP than for AFP-L3 (0.771 vs 0.669; P = 0.005) and significantly higher for “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP > 10 ng/mL” than for “PIVKA-II > 40 mAU/mL and AFP-L3 > 10%” (0.753 vs 0.683; P = 0.010). The direct comparisons indicated that the AUC of AFP-L3 was the lowest for both single and combined biomarkers; in other words, the inclusion of AFP-L3 did not improve the ability to distinguish between HCC and LC in our study.

This study was subject to several limitations. It had a retrospective design, the data were obtained in a single center, the study population was small, and the enrolled patients exhibited significantly different etiologies, with HBV or HCV infections among the HCC patients and alcoholic cause among the LC patients.

In conclusion, AFP was the most useful single biomarker for diagnosing HCC. Combining PIVKA-II with AFP improved the diagnostic performance, but adding AFP-L3 did not enhance the ability to distinguish between HCC and non-HCC LC. These results were unchanged after increasing the AFP cut-off value from 10 to 20 ng/mL.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, AFP-L3 = Lens culinaris-agglutinin-reactive fraction of AFP, AST = aspartate aminotransferase, AUC = area under the ROC curve, BCLC = Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV = hepatitis C virus, IQR = interquartile range, LC = liver cirrhosis, PIVKA-II = protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II, ROC = receiver-operating characteristic.

Authors’ contribution: Study design—SJP and JYJ; patients enroll and data collection—SWJ, YKC, SHL, SGK, S-WC, YSK, YDC, HSK, and BSK; laboratory data analysis—HIB; statistical analysis—SP; data analysis and writing—SJP.

Funding: This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific region: consensus statements. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat 2016;48:436–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Song do S, Bae SH. Changes of guidelines diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma during the last ten-year period. Clin Mol Hepatol 2012;18:258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Youk CM, Choi MS, Paik SW, et al. [Early diagnosis and improved survival with screening for hepatocellular carcinoma]. Taehan Kan Hakhoe Chi 2003;9:116–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chaiteerakij R, Addissie BD, Roberts LR. Update on biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:237–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Daniele B, Bencivenga A, Megna AS, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasonography screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;127:S108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lok AS, Sterling RK, Everhart JE, et al. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin and alpha-fetoprotein as biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2010;138:493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2010;4:439–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liebman HA, Furie BC, Tong MJ, et al. Des-gamma-carboxy (abnormal) prothrombin as a serum marker of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Koike Y, Shiratori Y, Sato S, et al. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin as a useful predisposing factor for the development of portal venous invasion in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective analysis of 227 patients. Cancer 2001;91:561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Miyagawa Y, et al. Prognostic significance of anatomical resection and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 1999;86:1032–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Marrero JA, Feng Z, Wang Y, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein, des-gamma carboxyprothrombin, and lectin-bound alpha-fetoprotein in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2009;137:110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sassa T, Kumada T, Nakano S, et al. Clinical utility of simultaneous measurement of serum high-sensitivity des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin and Lens culinaris agglutinin A-reactive alpha-fetoprotein in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;11:1387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shimauchi Y, Tanaka M, Kuromatsu R, et al. A simultaneous monitoring of Lens culinaris agglutinin A-reactive alpha-fetoprotein and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin as an early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in the follow-up of cirrhotic patients. Oncol Rep 2000;7:249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Durazo FA, Blatt LM, Corey WG, et al. Des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin, alpha-fetoprotein and AFP-L3 in patients with chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:1541–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fujiyama S, Izuno K, Yamasaki K, et al. Determination of optimum cut-off levels of plasma des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin and serum alpha-fetoprotein for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma using receiver operating characteristic curves. Tumour Biol 1992;13:316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pote N, Cauchy F, Albuquerque M, et al. Performance of PIVKA-II for early hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and prediction of microvascular invasion. J Hepatol 2015;62:848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gao J, Xu AF, Zheng HY, et al. [Clinical application studies on AFP-L3 detected by micro-spin column method]. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi 2010;24:461–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Taketa K, Endo Y, Sekiya C, et al. A collaborative study for the evaluation of lectin-reactive alpha-fetoproteins in early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 1993;53:5419–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Aoyagi Y, Isemura M, Yosizawa Z, et al. Fucosylation of serum alpha-fetoprotein in patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta 1985;830:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sato Y, Nakata K, Kato Y, et al. Early recognition of hepatocellular carcinoma based on altered profiles of alpha-fetoprotein. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1802–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kumada T, Toyoda H, Kiriyama S, et al. Predictive value of tumor markers for hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with hepatitis C virus. J Gastroenterol 2011;46:536–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shiraki K, Takase K, Tameda Y, et al. A clinical study of lectin-reactive alpha-fetoprotein as an early indicator of hepatocellular carcinoma in the follow-up of cirrhotic patients. Hepatology 1995;22:802–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kumada T, Nakano S, Takeda I, et al. Clinical utility of Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive alpha-fetoprotein in small hepatocellular carcinoma: special reference to imaging diagnosis. J Hepatol 1999;30:125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein-L3 and Golgi protein 73 may serve as candidate biomarkers for diagnosing alpha-fetoprotein-negative hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2016;9:123–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].[Practice guidelines for management of hepatocellular carcinoma 2009]. Korean J Hepatol 2009;15:391–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Amarapurkar D, Han KH, Chan HL, et al. Application of surveillance programs for hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific Region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:955–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003;362:1907–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, et al. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:817–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kim MN, Kim BK, Han KH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the Asia-Pacific region. J Gastroenterol 2013;48:681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Giannini EG, Sammito G, Farinati F, et al. Determinants of alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for its clinical use. Cancer 2014;120:2150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Harada T, Shigeta K, Noda K, et al. Clinical implications of alpha-fetoprotein in liver cirrhosis: five-year follow-up study. Hepatogastroenterology 1980;27:169–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rodriguez-Diaz JL, Rosas-Camargo V, Vega-Vega O, et al. Clinical and pathological factors associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis virus-related cirrhosis: a long-term follow-up study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mita Y, Aoyagi Y, Yanagi M, et al. The usefulness of determining des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin by sensitive enzyme immunoassay in the early diagnosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 1998;82:1643–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Saitoh S, Ikeda K, Koida I, et al. Serum des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin concentration determined by the avidin-biotin complex method in small hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer 1994;74:2918–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hadziyannis E, Sialevris K, Georgiou A, et al. Analysis of serum alpha-fetoprotein-L3% and des-gamma carboxyprothrombin markers in cases with misleading hepatocellular carcinoma total alpha-fetoprotein levels. Oncol Rep 2013;29:835–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Choi JY, Jung SW, Kim HY, et al. Diagnostic value of AFP-L3 and PIVKA-II in hepatocellular carcinoma according to total-AFP. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:339–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lim TS, Kim do Y, Han KH, et al. Combined use of AFP, PIVKA-II, and AFP-L3 as tumor markers enhances diagnostic accuracy for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kudo M. Japan's successful model of nationwide hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance highlighting the urgent need for global surveillance. Liver Cancer 2012;1:141–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kokudo N, Makuuchi M. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: the J-HCC guidelines. J Gastroenterol 2009;44(suppl 19):119–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Makuuchi M, Kokudo N, Arii S, et al. Development of evidence-based clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Hepatol Res 2008;38:37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.