Abstract

Objectives

To assess perspectives of patients with voice problems and identify factors associated with the likelihood of referral to voice therapy via the CHEER (Creating Healthcare Excellence through Education and Research) practice-based research network infrastructure.

Study Design

Prospectively enrolled cross-sectional study of CHEER patients seen for a voice problem (dysphonia).

Setting

The CHEER network of community and academic sites.

Methods

Patient-reported demographic information, nature and severity of voice problems, clinical diagnoses, and proposed treatment plans were collected. The relationship between patient factors and voice therapy referral was investigated.

Results

Patients (N = 249) were identified over 12 months from 10 sites comprising 30 otolaryngology physicians. The majority were women (68%) and white (82%). Most patients reported a recurrent voice problem (72%) and symptom duration >4 weeks (89%). The most commonly reported voice-related diagnoses were vocal strain, reflux, and benign vocal fold lesions. Sixty-seven percent of enrolled patients reported receiving a recommendation for voice therapy. After adjusting for sociodemographic and other factors, diagnoses including vocal strain/excessive tension and vocal fold paralysis and academic practice type were associated with increased likelihood of reporting a referral for voice therapy.

Conclusions

The CHEER network successfully enrolled a representative sample of patients with dysphonia. Common diagnoses were vocal strain, reflux, and benign vocal fold lesions; commonly reported treatment recommendations included speech/voice therapy and antireflux medication. Recommendation for speech/voice therapy was associated with academic practice type.

Keywords: CHEER, voice therapy, speech therapy, voice problems, voice disorders, dysphonia, reflux, vocal strain, vocal fold paralysis

Voice disorders are associated with negative quality-of-life impact, substantial indirect costs from voice-related work absenteeism and short-term disability claims, and direct health care cost estimates approaching $5 billion annually.1–3 Treatment for dysphonia may involve medical, surgical, and/or behavioral (voice) therapy. Voice therapy may be offered as the primary modality, an adjunct to medical or surgical treatment, or a means to aid in diagnosis.4 Voice therapy has been shown to be effective in patients with muscle tension dysphonia,5,6 phonotraumatic benign vocal fold lesions,7–10 age-related vocal fold atrophy,11 neurologic disorders (including Parkinson’s disease),12,13 and reflux-related14 voice disorders. To date, most studies of voice therapy have been conducted in academic tertiary voice clinics, while other investigations regarding the utilization of voice therapy employed surveys of otolaryngologists, which may be subject to recall bias.15–19

As voice disorders are commonly seen in a variety of settings,20 broadening our knowledge regarding the diagnosis of voice disorders and voice therapy referral patterns/utilization is necessary. Creating Healthcare Excellence through Education and Research (CHEER),21 a practice-based research network focused on hearing and communication disorders, is based on a collaborative model of academic and community partnerships in otolaryngology and had an initial focus on hearing and balance with previously reported data on patients with tinnitus and/or dizziness.21 The CHEER network is an ideal platform for investigating practice and treatment patterns of various otolaryngologic disorders across multiple centers in the United States. Utilizing a practice-based research network to collect the data engages a broad range of interdisciplinary care sites and settings and accesses a diverse population of patients, ensuring that the information collected supports expedient translation. We hypothesized that the functionality of the CHEER network could be successfully utilized to study questions related to voice disorders. We aimed to characterize the patient population by assessing sociodemographics and vocal symptom levels as well as self-reported voice-related diagnoses and treatment recommendations. We also sought to understand what factors predicted the likelihood of referral for voice therapy.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

A brief survey of CHEER sites was conducted in March 2012. The survey identified the number of otolaryngologists and speech-language pathologists who treat voice problems in their practice, and it provided estimates of monthly visits and referrals for patients with voice problems. Sites reporting interest and adequate relevant patient volumes were invited to participate. Of the 24 active CHEER network sites, 10 participated in the current study. Fourteen sites, 7 academic and 7 private practice, responded to the initial survey, with 11 agreeing to participate; 1 did not enroll patients.

New patients with a voice complaint were invited to complete a brief survey that included demographic data, voice diagnoses, severity of voice problems, treatment recommendations, and outcomes. All data were self-reported by patients at the end of their clinic visits, including sociodemographic factors, diagnoses, and receipt of voice therapy recommendation. We did not have access to providers’ diagnoses or ICD-9 codes. All participants were ≥18 years old. Sites were categorized as academic versus nonacademic based on affiliation with a teaching medical school; completion of laryngology fellowship and availability of speech-language pathologists within the practice were assessed through publicly available information listed on practice websites, with additional inquiries via phone as needed. A total of 249 patients were identified for analysis after exclusion of patients who were missing data on sex, age, and voice therapy recommendations (n = 40).

Measures

To collect patient-reported data on diagnoses and treatment recommendations, multiple-choice questions were utilized. Participants were asked, “What is your diagnosis? Please mark all that apply.” Multiple options were provided as possible responses, as well as the option of specifying “other” or “not sure.” We used affirmative responses to the question “Was voice therapy recommended for you at today’s visit?” to identify patients who received a voice therapy recommendation. In addition, the Voice Handicap Index–10, a well-established scale reflecting patient opinions about how the voice has affected quality of life, was collected.22 To protect patient privacy, surveys were assigned unique identifiers. The Duke University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study and extended to CHEER community sites. IRB approvals were also obtained from CHEER sites that required independent IRB approval. Project enrollment began on November 27, 2012, and continued through December 5, 2013, when the recruitment goal was met. Analysis of de-identified data was deemed exempt by the IRB of the University of Minnesota.

Study data were collected and managed through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Duke University.23 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. Data were extracted from the REDCap database and analyzed via SAS 9.3 (Statistical Analysis Software Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Analytic Methods

Bivariate comparisons were used to evaluate socioeconomic factors and the distributions of reported voice-related diagnoses and treatment recommendations. The factors associated with a voice therapy recommendation were then assessed, controlling for age, sex, race, and educational attainment, via a multivariate regression model. Because units (individual patients) were clustered within CHEER sites and a single participant could have multiple diagnoses, generalized estimating equations models with clustered standard errors were used. To optimize model fit, only diagnoses in the upper 2 quartiles (ie, the most common) were employed as covariates, although all patients were included in the analysis regardless of diagnosis.24 The generalized estimating equation regression models controlled for individual demographic and clinical covariates, including age, sex, race, education, self-reported diagnosis, and site status (academic and nonacademic). Because income and education were closely collinear and self-reported income is frequently inaccurate, income was excluded from our model. We also excluded tobacco use a priori in the model due to its potentially differential effects on a subset of the diagnoses. Sensitivity analysis confirmed that model fit was superior when tobacco use was excluded. The primary goal in this context was to examine factors associated with patient-reported voice therapy recommendation.

Results

Description of the Practice-Based Research Network

Of the 24 active CHEER network sites, 10 participated in the current study. Participating sites were located in Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia. Of the 10 sites, 6 had at least 1 fellowship-trained laryngologist, and 3 others had general otolaryngologists with a practice interest in laryngology. This constituted 30 otolaryngology physicians. Eighty percent of practices had ≥1 speech-language pathologists practicing out of the same office; 50% of practices were affiliated with an academic teaching hospital; and the other 50% were in private practice settings. The 5 academic sites enrolled a total of 145 patients (58%), and the 5 private sites enrolled a total of 104 patients (42%).

Description of the Population

Of all participants, 68% were women, and 82% were white. More than half the participants were >50 years old (66%), earned >$40,000 (62%), and had a bachelor degree or higher (52%). Patient sociodemographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Population: CHEER Network (N = 249).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 80 | 32 |

| Female | 169 | 68 |

| Race | ||

| White | 204 | 82 |

| Black or African American | 23 | 9 |

| Other | 22 | 9 |

| Age, y | ||

| 18–29 | 22 | 9 |

| 30–39 | 25 | 10 |

| 40–49 | 37 | 15 |

| 50–64 | 103 | 41 |

| 65+ | 62 | 25 |

| Income | ||

| ≤$20,000 | 23 | 9 |

| >$20,000 to $40,000 | 33 | 13 |

| >$40,000 to $60,000 | 35 | 14 |

| >$60,000 | 120 | 48 |

| Don’t know | 38 | 15 |

| Educationa | ||

| High school or GED | 80 | 33 |

| Associate degree | 35 | 14 |

| BA, BS (4-y college degree) | 66 | 27 |

| MA, MS (master degree) | 47 | 19 |

| PhD, MD, JD (or other doctoral degree) | 15 | 6 |

| Tobacco use | ||

| Never | 145 | 59 |

| Currently use | 24 | 10 |

| Quit | 78 | 31 |

Six patients did not report education status, and 2 did not report information on tobacco use.

Voice Problem Characteristics and Severity

When asked to describe the frequency and severity of their voice problem, 89% of patients reported that it persisted for >4 weeks (Table 2). However, only 22% reported having to miss ≥1 days of work in the last year; 56% of patients reported having a continual voice problem as opposed to an “off and on” problem. The Voice Handicap Index–10 score varied, but most patients (79%) had a score ranging from 10 to 29 (mean ± SD, 17.9 ± 8.0).

Table 2.

Voice Problem Characteristics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Voice problem frequencya | ||

| Once | 68 | 28 |

| More than once | 175 | 72 |

| Pattern of voice problemb | ||

| Continual | 136 | 56 |

| Off and on | 108 | 44 |

| Duration of voice problem, wk | ||

| <2 | 10 | 4 |

| 2–4 | 17 | 7 |

| >4 | 216 | 89 |

| Work missed within past year,c d | ||

| None | 167 | 71 |

| <1 | 14 | 6 |

| 1–3 | 25 | 11 |

| 4–6 | 4 | 1 |

| >6 | 24 | 10 |

| Voice Handicap Index–10 | ||

| 0–9 | 31 | 12 |

| 10–19 | 131 | 53 |

| 20–29 | 61 | 25 |

| 30–40 | 26 | 10 |

Missing, n = 6.

Missing, n = 5.

Missing, n = 15.

Patient-Reported Diagnoses

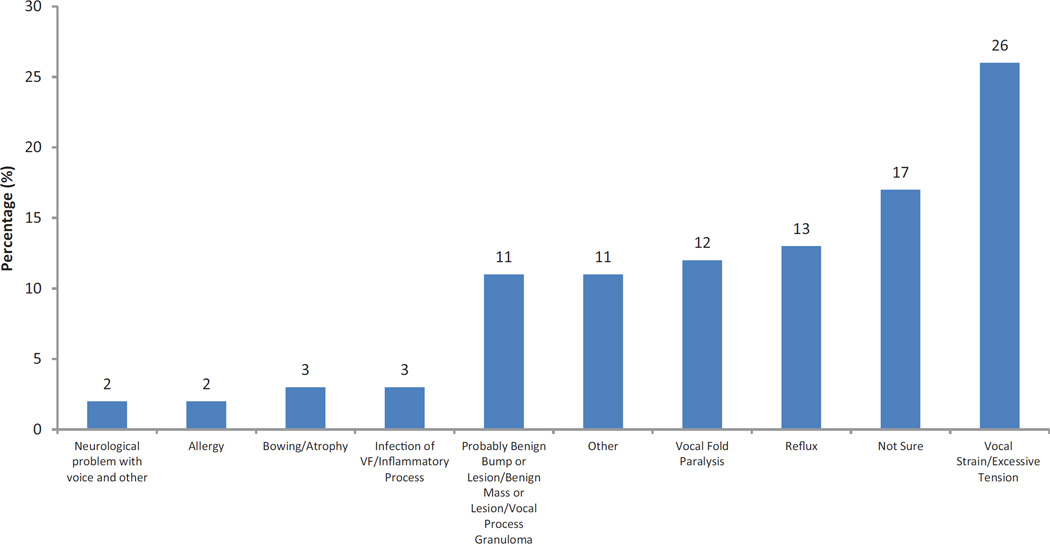

Just over half the patients self-reported receiving a single diagnosis (54%). Among these, vocal strain/excessive tension (26%), reflux (13%), and vocal fold paralysis (12%) were reported the most frequently (Figure 1). Seventeen percent of patients reported being “not sure” about their diagnosis. The majority of patients with vocal strain/excessive tension and vocal fold paralysis were seen in an academic setting (71% and 79%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Diagnoses of CHEER patients self-reporting only 1 diagnosis. VF, vocal fold.

Forty-six percent of patients reported multiple diagnoses. Among patients reporting multiple diagnoses, reflux (28%), vocal strain/excessive tension (27%), and allergy (16%) were the most frequently reported (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diagnoses of CHEER patients self-reporting multiple diagnoses (≥2). Percentage sum is >100, as patients were able to choose multiple diagnoses. VF, vocal fold.

Patient-Reported Treatment Recommendations

Among patients who reported receiving a single treatment recommendation, referral for speech therapy or voice therapy was most frequent (34%; Figure 3). Other common treatment types for patients reporting a single treatment recommendation included antireflux medication (17%), surgery (8%), and speech pathology referral for stroboscopy (8%).

Figure 3.

Percentage of self-reported treatment recommendations of patients reporting only 1 treatment in CHEER. Note that diet/life-style modifications for reflux, steroid inhaler to use by mouth, reflux test, consult with gastroenterologist, consult with pulmonologist, consult with allergist, voice amplification antibiotic, allergy, imaging (eg, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging), consult with neurologist, voice rest, and Botox/botulinum toxin injection treatment recommendations together accounted for 7% of patient self-reported treatment recommendations and are excluded from this figure. SLP, speech-language pathologist.

Fifty-nine percent of patients reported receiving multiple treatment recommendations. Among those, the most frequently mentioned treatments were antireflux medication (59%), referral to speech pathology for speech therapy or voice therapy (50%), and voice lessons (21%; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of self-reported treatment recommendations of patients reporting multiple treatment recommendations in CHEER. SLP, speech-language pathologist. Consult with allergist, steroid inhaler to use by mouth, consult with pulmonologist, Botox/botulinum toxin injection, reflux test, consult with gastroenterologist, and antibiotic and steroid treatment together accounted for <5% of treatments and are excluded from this figure. Percentage sum is >100, as patients were able to choose multiple diagnoses.

Overall, 67% of patients received a recommendation for speech/voice therapy and 40% for reflux management.

Recommendation for Voice Therapy

The diagnostic categories from which the greatest proportions of patients reported a speech/voice therapy recommendation were (1) vocal strain/excessive tension (92 of 107, 86%), (2) neurologic problem (voice and/or other; 6 of 7, 86%), and (3) irritable larynx syndrome (22 of 26, 85%; Table 3). After multivariable regression including adjustment for other covariates, the factors most strongly associated with a voice therapy recommendation were (1) diagnoses including vocal strain/excessive tension and vocal fold paralysis and (2) academic site (Table 4).

Table 3.

Diagnoses and Referral to Voice Therapy.

| Voice Therapy Recommended

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | n | % | |

| Vocal strain / excessive tension | 107 | 92 | 86 |

| Neurologic problem (voice only) / neurologic problem with voice and other symptoms | 7 | 6 | 86 |

| Irritable larynx | 26 | 22 | 85 |

| Vocal fold paralysis | 39 | 31 | 79 |

| Scarring | 9 | 7 | 78 |

| Bowing/atrophy | 16 | 12 | 75 |

| Probably benign bump / benign mass or lesion / mass or lesion / vocal process granuloma | 53 | 39 | 74 |

| Reflux | 88 | 57 | 65 |

| Allergy | 43 | 25 | 58 |

| Not sure | 30 | 15 | 50 |

| Infection of vocal fold / inflammatory process | 17 | 8 | 47 |

| Other | 13 | 6 | 46 |

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Reported Voice Therapy Recommendation.

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| White | Referent | ||

| Black or African American | 0.81 | 0.50–1.31 | .39 |

| Other | 0.62 | 0.38–1.02 | .06 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.17 | 0.69–1.97 | .55 |

| Male | Referent | ||

| Age, y | |||

| 18–39 | Referent | ||

| 40–59 | 1.43 | 0.73–2.81 | .29 |

| 60+ | 1.65 | 0.86–1.21 | .27 |

| Education | |||

| High school or GED | 0.73 | 0.53–1.01 | .05 |

| Associate degree / BA, BS (4-y college degree) | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | .81 |

| MA, MS (master degree) / PhD, MD, JD / other doctoral degree | Referent | ||

| Diagnosis | |||

| Vocal strain / excessive tension | 5.74 | 3.25–10.1 | <.0001 |

| Vocal fold paralysis | 1.80 | 1.48–2.20 | <.0001 |

| Probably benign bump / benign mass or lesion / mass or lesion / vocal process granuloma | 1.88 | 0.98–3.60 | .06 |

| Reflux | 1.09 | 0.20–2.04 | .26 |

| Allergy | 0.64 | 0.93–1.27 | .45 |

| Site status | |||

| Academic | 5.62 | 5.38–5.87 | <.0001 |

| Nonacademic | Referent |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the CHEER infrastructure is a valuable resource for investigating dysphonia. This CHEER cohort comprised a sizable group of adults with dysphonia from a broad geographic distribution, and the racial distribution was similar to that described in the overall CHEER cohort.25 Income and educational information were not available on the overall CHEER cohort, but the enrolled group was similar to voice patient populations that have been described in the past, with a female preponderance (in contrast to the overall CHEER cohort) and a majority reporting white race.25–28 The degree of voice-related handicap reported by the group was generally consistent with what might be expected, with the majority reporting a Voice Handicap Index–10 above the cutoff for “abnormal.”29 In contrast to prior findings,27 a relative minority reported missing work related to the voice problem. However, similar to prior reports,27 most patients indicated having a recurrent or long-standing voice problem, thereby raising the possibility of voice-related presenteeism,30 which was not assessed.

Diagnoses

About half of patients reported a single diagnostic category, and of those, “not sure” was most common. Although this represented only 7% of the overall enrolled population, it was nevertheless an unexpected finding and may point to an opportunity to improve patient-provider communication. It is possible that some patients did not understand what was explained to them. Alternatively, otolaryngologists have been reported to be less comfortable diagnosing voice disorders without obvious structural abnormalities; thus, it is possible that workup and/or diagnostic decision making was still in progress.31 Finally, it is possible that the patient had received a prior diagnosis that was not the same as the newly given diagnosis, which frequently occurs following specialty evaluation of a voice problem,32,33 thereby potentially resulting in some uncertainty. Although this level of detail was not available for analysis in the current data set, patient comprehension and communication with the otolaryngologist, as well as subsequent patient outcomes, are important areas for future research.

Reflux, allergy, muscle tension dysphonia, and benign vocal fold lesions were commonly reported diagnoses. Reflux is a prominent comorbid diagnosis in this group of patients with voice complaints and reflects the prevalent perception among otolaryngologists that reflux plays an important role in voice disorders.34,35 The link between allergy and dysphonia is poorly understood, with some authors reporting a high prevalence of allergies among patients with dysphonia36,37 and others indicating that the allergy diagnosis may be revised upon specialty or subspecialty assessment of dysphonia.38 The prevalence of muscle tension dysphonia and benign vocal fold lesions in this study was similar to that in other populations presenting with dysphonia.39,40

Treatments

There were some minor differences in the distribution of treatment recommendations between those receiving 1 and >1 recommendations, but in both groups, speech therapy and reflux medications were most common. For nearly all diagnostic groups (except “inflammatory/infections” and “other”), the majority reported a recommendation for voice therapy. With 60% of practices having a laryngologist with fellowship training, 30% having otolaryngologists interested in voice, and 80% having a speech-language pathologist in the same practice, the frequency of voice therapy utilization in CHEER is likely greater than that of other practice settings without the same degree of voice-related interest and/or expertise. A study based on data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found a 12.5% referral rate among otolaryngologists for speech-language pathology evaluation/treatment,41 while one based on a national claims database identified a referral rate of only 5% among otolaryngologists42; variable rates of referral may reflect practice-level differences in voice-related expertise or preferences.

Multivariable regression adjusting for potentially confounding variables indicated that vocal strain/excessive tension was associated with a 5.7-fold increased likelihood of referral, consistent with the wide acceptance of voice therapy as the primary mode of treatment. We also found that vocal fold paralysis was associated with a 1.8-fold increased likelihood of referral (P < .0001). This finding is of interest because the role of voice therapy in the management of vocal fold paralysis has not been clearly defined.43–45 Our data do not differentiate among voice therapy referral for indirect voice therapy only, voice therapy as an adjunct to concurrent or planned surgical treatment, or voice therapy as the primary treatment modality. Given our finding that the diagnosis of vocal fold paralysis increases the likelihood of voice therapy referral, future studies are warranted examining the use of voice therapy in the management of vocal fold paralysis. Diagnoses of benign vocal fold lesions/granuloma were not associated with an increased likelihood of voice therapy referral (P = .06). This was somewhat surprising, since it is commonly accepted that voice therapy is often the first-line treatment for certain phonotraumatic lesions as well as for vocal process granulomas,46 but this may also reflect individual practice differences or other unmeasured factors.

Academic practice setting was strongly associated with increased likelihood of reported referral to speech/voice therapy (odds ratio, 5.62; P < .0001), even though the analysis was adjusted for all other factors, including diagnoses. This may be a reflection of the likelihood of having fellowship-trained laryngologists, as the 2 variables were nearly completely linked, rather than a result of having or not having speech pathologists on site. Alternatively, it could reflect underlying differences in diagnosis mix, referral patterns, or reimbursement or other structural differences that influence practice patterns. For example, it was recently observed that coassessment with a speech pathologist and laryngologist is associated with higher likelihood of recommendation for and utilization of speech therapy services.47 Thus, even among practice sites with voice interest/expertise, there was varied use of voice therapy. This variability in treatment may have implications for patient outcomes.

Limitations

Although these data demonstrate the feasibility and value of collecting data through a practice-based network to learn about the experiences of patients with dysphonia, a number of limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the diagnostic and treatment data presented here are by self-report, which was the intended study design. Future work will include the examination of similarities and differences between patient and provider report of diagnostic and treatment data. Second, as this was a cross-sectional study, we did not collect longitudinal follow-up, ask follow-up questions, or obtain medical records for further information. Third, patient report of treatment recommendations such as speech therapy does not necessarily translate directly to speech therapy attendance or adherence,48 particularly among those with severe voice-related quality-of-life changes,49 but the CHEER network may be a useful framework within which to investigate longitudinal questions in the future.

Conclusions

The CHEER practice-based research network successfully enrolled a representative cohort of patients with dysphonia. Most reported long-standing or recurrent dysphonia. The most commonly reported diagnoses were reflux and vocal strain, and most commonly reported treatment recommendations were antireflux medications and speech/voice therapy. Academic practice site was predictive of the likelihood of referral to speech/voice therapy. The study identified a possible need for improved patient-provider communication regarding the nature of the voice disorder. Investigation of voice therapy adherence and predictors of adherence among a multicentered cohort of patients may identify areas for improved treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply thankful to Kristine Schulz, DrPH, MPH, for study management; Erika Juhlin for administrative support; Amy Walker for regulatory and coordinator support and facilitation with the sites; David Witsell MD, MHS, and Debara Tucci, MD, MBA, MS, as principal investigators for the parent grant; Meaghan House, MPH, for assistance with data handling; and especially our participating CHEER site investigators and coordinators and their patients for their gracious willingness and enthusiasm in taking part in this research effort.

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: National Institutes of Health (3R33DC00863205S1 and UL1TR000114). National Institutes of Health provided funding for data collection and was not involved in study design/conduct, data collection/analysis/interpretation, or writing/approval of manuscript. We would like to thank the AAO-HNSF and the CHEER Network, whose collaborative initiatives make this work possible via the CHEER grant (NIH #5U24DC012206-02).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions

Stephanie Misono, study conception, data interpretation, critical revision, final approval, study integrity; Schelomo Marmor, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision, final approval, study integrity; Nelson Roy, study conception, data interpretation, critical revision, final approval, study integrity; Ted Mau, data acquisition and interpretation, critical revision, final approval, study integrity; Seth M. Cohen, study conception, data acquisition and interpretation, critical revision, final approval, study integrity.

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Cohen SM, Dupont WD, Courey MS. Quality-of-life impact of non-neoplastic voice disorders: a meta-analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:128–134. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, Asche C, Courey M. Direct health care costs of laryngeal diseases and disorders. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1582–1588. doi: 10.1002/lary.23189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, Asche C, Courey M. The impact of laryngeal disorders on work-related dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1589–1594. doi: 10.1002/lary.23197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy N, Barkmeier-Kraemer J, Eadie T, et al. Evidence-based clinical voice assessment: a systematic review. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;22:212–226. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2012/12-0014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts CR, Hamilton A, Toles L, Childs L, Mau T. A randomized controlled trial of stretch-and-flow voice therapy for muscle tension dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1420–1425. doi: 10.1002/lary.25155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts CR, Diviney SS, Hamilton A, Toles L, Childs L, Mau T. The effect of stretch-and-flow voice therapy on measures of vocal function and handicap. J Voice. 2015;29:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SM, Garrett CG. Utility of voice therapy in the management of vocal fold polyps and cysts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:742–746. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murry T, Woodson GE. A comparison of three methods for the management of vocal fold nodules. J Voice. 1992;6:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sulica L, Behrman A. Management of benign vocal fold lesions: a survey of current opinion and practice. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:827–833. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verdolini-Marston K, Burke MK, Lessac A, Glaze L, Caldwell E. Preliminary study of two methods of treatment for laryngeal nodules. J Voice. 1995;9:74–85. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mau T, Jacobson BH, Garrett CG. Factors associated with voice therapy outcomes in the treatment of presbyphonia. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1181–1187. doi: 10.1002/lary.20890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liotti M, Ramig L. Improvement of voicing in patients with Parkinson’s disease by speech therapy. Neurology. 2003;61:1316. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.9.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramig LO, Verdolini K. Treatment efficacy: voice disorders. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1998;41:S101–S116. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4101.s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vashani K, Murugesh M, Hattiangadi G, et al. Effectiveness of voice therapy in reflux-related voice disorders. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Lierde KM, Claeys S, De Bodt M, van Cauwenberge P. Long-term outcome of hyperfunctional voice disorders based on a multiparameter approach. J Voice. 2007;21:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews ML, Schmidt CP. Congruence in personality between clinician and client: relationship to ratings of voice treatment. J Voice. 1995;9:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crane SL, Cooper EB. Speech-language clinician personality variables and clinical effectiveness. J Speech Hear Disord. 1983;48:140–145. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4802.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Leer E, Hapner ER, Connor NP. Transtheoretical model of health behavior change applied to voice therapy. J Voice. 2008;22:688–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behrman A. Facilitating behavioral change in voice therapy: the relevance of motivational interviewing. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2006;15:215–225. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2006/020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, Asche C, Courey M. Prevalence and causes of dysphonia in a large treatment-seeking population. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:343–348. doi: 10.1002/lary.22426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witsell DL, Rauch SD, Tucci DL, et al. The Otology Data Collection project: report from the CHEER network. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:572–580. doi: 10.1177/0194599811416063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, Zullo T, Murry T. Development and validation of the Voice Handicap Index-10. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1549–1556. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creating Healthcare Excellence through Education and Research. Retrospective Data Collection Project. [Accessed January 15, 2016]; http://cheerresearch.org/projects/retrospective-data-collection-project/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy N, Merrill RM, Gray SD, Smith EM. Voice disorders in the general population: prevalence, risk factors, and occupational impact. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1988–1995. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000179174.32345.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen SM. Self-reported impact of dysphonia in a primary care population: an epidemiological study. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2022–2032. doi: 10.1002/lary.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharyya N. The prevalence of voice problems among adults in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2359–2362. doi: 10.1002/lary.24740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arffa RE, Krishna P, Gartner-Schmidt J, Rosen CA. Normative values for the Voice Handicap Index-10. J Voice. 2012;26:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer TK, Hu A, Hillel AD. Voice disorders in the workplace: productivity in spasmodic dysphonia and the impact of botulinum toxin. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(suppl 6):S1–S14. doi: 10.1002/lary.24292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen SM, Pitman MJ, Noordzij JP, Courey M. Evaluation of dysphonic patients by general otolaryngologists. J Voice. 2012;26:772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen SM, Dinan MA, Roy N, Kim J, Courey M. Diagnosis change in voice-disordered patients evaluated by primary care and/or otolaryngology: a longitudinal study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150:95–102. doi: 10.1177/0194599813512982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, Wilk A, Thomas S, Courey M. Change in diagnosis and treatment following specialty voice evaluation: a national database analysis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1660–1666. doi: 10.1002/lary.25192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Book DT, Rhee JS, Toohill RJ, Smith TL. Perspectives in laryngopharyngeal reflux: an international survey. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1399–1406. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed TF, Khandwala F, Abelson TI, et al. Chronic laryngitis associated with gastroesophageal reflux: prospective assessment of differences in practice patterns between gastroenterologists and ENT physicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:470–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randhawa PS, Nouraei S, Mansuri S, Rubin JS. Allergic laryngitis as a cause of dysphonia: a preliminary report. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2010;35:169–174. doi: 10.3109/14015431003599012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth DF, Ferguson BJ. Vocal allergy: recent advances in understanding the role of allergy in dysphonia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:176–181. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32833952af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keesecker SE, Murry T, Sulica L. Patterns in the evaluation of hoarseness: time to presentation, laryngeal visualization, and diagnostic accuracy. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:667–673. doi: 10.1002/lary.24955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Houtte E, Van Lierde K, D’Haeseleer E, Claeys S. The prevalence of laryngeal pathology in a treatment-seeking population with dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:306–312. doi: 10.1002/lary.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coyle SM, Weinrich BD, Stemple JC. Shifts in relative prevalence of laryngeal pathology in a treatment-seeking population. J Voice. 2001;15:424–440. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(01)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Best SR, Fakhry C. The prevalence, diagnosis, and management of voice disorders in a National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) cohort. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:150–157. doi: 10.1002/lary.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen SM, Dinan MA, Kim J, Roy N. Otolaryngology utilization of speech-language pathology services for voice disorders. Laryngoscope. doi: 10.1002/lary.25574. [published online August 26, 2015] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller S. Voice therapy for vocal fold paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37:105–119. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Behrman A. Evidence-based treatment of paralytic dysphonia: making sense of outcomes and efficacy data. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37:75–104. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider SL. Behavioral management of unilateral vocal fold paralysis and paresis. Perspectives on Voice and Voice Disorders. 2012;22:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SW, Hong HJ, Choi SH, et al. Comparison of treatment modalities for contact granuloma: a nationwide multicenter study. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1187–1191. doi: 10.1002/lary.24470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Litts JK, Gartner-Schmidt JL, Clary MS, Gillespie AI. Impact of laryngologist and speech pathologist coassessment on outcomes and billing revenue. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:2139–2142. doi: 10.1002/lary.25349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portone C, Johns MM, 3rd, Hapner ER. A review of patient adherence to the recommendation for voice therapy. J Voice. 2008;22:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duarte de Almeida L, Santos LR, Bassi IB, Teixeira LC, Cortes Gama AC. Relationship between adherence to speech therapy in patients with dysphonia and quality of life. J Voice. 2013;27:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]