Abstract

This study analyzed the content of 125 unique reports published since 1990 that have examined the health and well-being—as well as the interpersonal and contextual experiences—of sexual minority youth of color (SMYoC). One-half of reports sampled only young men, 73% were noncomparative samples of sexual minority youth, and 68% of samples included multiple racial-ethnic groups (i.e., 32% of samples were mono-racial/ethnic). Most reports focused on health-related outcomes (i.e., sexual and mental health, substance use), while substantially fewer attended to normative developmental processes (i.e., identity development) or contextual and interpersonal relationships (i.e., family, school, community, or violence). Few reports intentionally examined how intersecting oppressions and privileges related to sexual orientation and race-ethnicity contributed to outcomes of interest. Findings suggest that research with SMYoC has been framed by a lingering deficit perspective, rather than emphasizing normative developmental processes or cultural strengths. The findings highlight areas for future research focused on minority stress, coping, and resilience of SMYoC.

Keywords: Health, qualitative methods, racial-ethnic identity, sexual orientation, social inequality

Adolescence and young adulthood are critical developmental periods for self-awareness and exploration of identification with specific social groups (e.g., ethnic-racial identity, sexual identity; Erikson, 1968; Quintana, 1999; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Advancements in social-cognitive maturity allow adolescents and young adults (collectively referred to as “youth” from this point forward) to conceptualize and understand their own experiences in terms of the experiences, expectations, and future possibilities shared by other members in their social group (e.g., members who share racial-ethnic group membership; Quintana, 1999; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). At the same time, youth become more sensitive to perceptions of acceptance or exclusion based on their membership in these social groups (Rutland, Hitti, Mulvey, Abrams, & Killen, 2015; Teichman, Bar-Tal, & Abdolrazeq, 2007). Several studies of sexual minority youth (e.g., Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012; Saewyc, 2011) and youth of color (YoC) (e.g., Huynh & Fuligni, 2010; Simons et al., 2006) have found that encountered bias (e.g., discrimination, bias-based school victimization) uniquely contributes to adjustment, an important finding given the well-documented health and academic disparities among sexual minority youth (SMY; Institutes of Medicine [IOM], 2011) and YoC (Satcher, 2001).1 Yet few studies have examined how the interaction between sexual orientation and race-ethnicity operates as an underlying mechanism of disparate health outcomes among adolescents (IOM, 2011). Further, despite discussions and critical reviews of intersections of sexual orientation and race-ethnicity among adults (Huang et al., 2009; Wilson & Harper, 2013), the literature focused on sexual minority youth of color (SMYoC) largely remains unintegrated.

Given the considerable demographic shifts occurring in the Unites States—with the projection that by 2020, the population of racial and ethnic minority youth will surpass the non-Latino White youth population (Colby & Ortman, 2015)—it is increasingly important to understand what is (and what is not) known about the intersections between race-ethnicity and other marginalized identities, such as sexual orientation. This content analysis and critical review examined what is known about the intersection of sexual orientation and race-ethnicity among youth in order to broaden understandings and conceptualizations of risk and resilience for SMYoC. Of note, our review is largely focused on the experiences of Black and Latino SMY given that the majority of the research has focused on these two groups. Throughout our review, we refer to the race or ethnicity of the population being studied consistent with the initial reports (e.g., African American, Black, African American/Black; Asian, Asian Pacific Islander, etc.).

An integrated understanding of how multiple marginalized identities contributes to adolescent development is a critical first step needed to inform future research and subsequent intervention strategies aimed at improving well-being among marginalized youth populations. Our content analysis and critical review of the literature included three aims: (a) to examine what content areas are (in)frequently studied among SMYoC, (2) to examine who (e.g., gender, race-ethnicity, sexual orientation) was represented in the extant literature on SMYoC, and (3) to summarize and critique the extant research published in this area, identifying limitations and promising areas for future research. We expected that the literature would be focused on problematic outcomes, rather than normative developmental outcomes, given that the study of adolescence, in general, has largely been a science grounded in pathology (Russell, 2016). This pathologizing-normative disparity is further compounded when the focus is on marginalized populations (e.g., Coll et al., 1996; IOM, 2011) and because NIH-funded studies are typically framed by a medical model that is aimed at understanding pathology and risk (Coulter, Kenst, & Bowen, 2014).

Method

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion in the analysis, reports had to include (a) original empirical results (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research) focused on SMYoC, (b) participants aged 25 years and younger, and (c) participants living in the United States. The upper age limit of 25 years was chosen in order to be consistent with theories of emerging adulthood that posit that the developmental experiences of youth in their early 20s are distinct from the experiences of individuals in their late 20s (Arnett, 2014); further, several reports (n = 18) would have been arbitrarily excluded from our analysis had our inclusion criteria been age 24 rather than 25. We limited the review to only include U.S.-focused samples given the unique sociocultural and historical salience of race-ethnicity in the United States (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Finally, we included reports with either an explicit (e.g., within-group reports of SMY of a particular race-ethnicity) or implicit (e.g., reports of SMY that examined race-ethnicity as a covariate) focus on the intersection between race-ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Search and categorization strategies

Search terms were truncated (indicated by ‘∗’) to allow for diversity of term usage across reports. Search terms included (lesbian OR bisexual OR gay OR queer OR questioning OR “sexual minority” OR LGBT OR LGB OR “same-sex attracted” OR “both-sex attracted” OR MSM OR WSM OR “sexual orientation” OR “sexual identity”) AND (“ethnic minority” OR “racial minority” OR Asian OR Latino OR Hispanic OR Black OR “African American” OR “youth of color”) AND (youth∗ OR adol∗ OR child∗ OR and teen∗). Several comprehensive databases were used, including ERIC, Medline, PsycInfo, and Sociological Abstracts. Unpublished dissertations were included in this review in order to minimize the threat of publication bias, given that null or unexpected findings are less likely to be published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., Card, 2011).

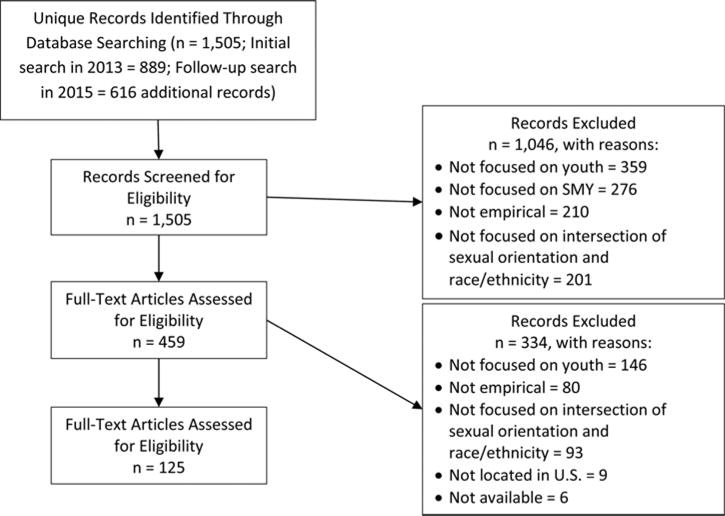

Two searches, one in 2013 and a follow-up in 2015, yielded 1,507 unique reports (see Figure 1 for screening and selection procedures and results). The research team—two faculty members and three students—categorized the resulting 125 reports according to the following characteristics: design utilized (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods; sample size; location), participant characteristics (i.e., gender, sexual orientation, race-ethnicity, age), and the constructs of interest examined in each report (e.g., sexual health, depression, family relationships). The coding system for the constructs of interest examined in each report was developed inductively by focusing on the report’s dependent and independent variables; eight content categories emerged and are discussed in the following sections. This strategy is consistent with the methodology used in other relevant content reviews (Charmaraman, Woo, Quach, & Erkut, 2014; Kaestle & Ivory, 2012). Reliability was assessed throughout the process (10% of reports were coded twice), and any discrepancies in coding were discussed and reconciled as a team.

Figure 1.

Diagram reporting screening and selection procedures. SMY = sexual minority youth.

Results

Report design and participant characteristics

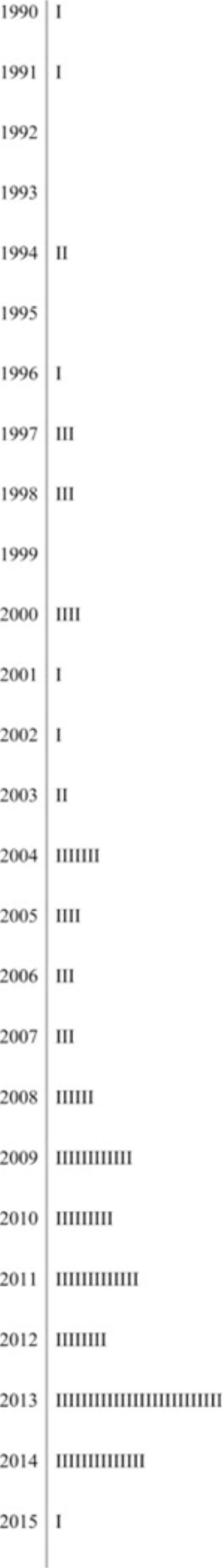

Of the 125 reports (see Table 1), 66.4% were quantitative; 25.6% were qualitative; and 8% were mixed methods. Sample size varied widely across reports (Mdn =180; Mean = 4,919.10, SD = 15,516.36; Range: 1–92,470); nearly half of the reports (48%) contained samples with at least 200 participants, and only 10 reports included samples with fewer than 10 participants. Few reports focused exclusively on participants aged 20 or younger (i.e., early to late adolescence [~12 to 20 years]; 36.8%). The number of reports addressing the intersection between race-ethnicity and sexual orientation has increased tremendously in the past 5 to 10 years (see Figure 2); over two-thirds of the reports included in this review were published after 2008.

Table 1.

Articles included in each topic area.

Note. Several reports covered more than one topic and are listed under each relevant category.

Figure 2.

Plot of the years that reports included were published. I = 1 report.

Regarding participant demographics, 50.4% of the reports included only young men; only 8% of samples included only young women. Less than 10% of reports (n = 12) explicitly included transgender youth when enumerating gender identity categories. Most reports included samples with multiple racial-ethnic groups (n = 82; 66%); monoethnic reports included exclusively African American or Black youth (n = 31; 25%), Latino or Hispanic youth (n = 7; 5.6%), and Asian or Pacific Islander youth (n = 5; 4%). Only 34.4% of reports included heterosexual or straight youth; most were focused on the within-group experiences of young men who have sex with men (MSM), young women who have sex with women (WSW), or lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer/questioning (LGBQ) identified youth. Notably, almost one-third of the reports (32%) focused on MSM populations.

Finally, the majority of reports focused on health-related outcomes: 69 focused on sexual health (e.g., AIDS/HIV), 42 on mental health (e.g., depressive symptoms), and 43 on substance use. Few reports examined intersectionality in terms of normative developmental processes, such as sexual orientation identity development (n = 22) or contextual and interpersonal relationships (schools [n = 10]; families [n = 19]; communities [n = 12]; violence [n = 20]).

Health-focused outcomes

Sexual health

Most of the 69 reports focused on sexual health only sampled sexual minorities (n = 54; 78%), and 37 of those 69 reports (54%) only sampled young MSM populations. Forty-one percent of reports (n = 28) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group; 22 of these reports included only African American or Black youth. Only a few of the reports examined their research questions or hypotheses using an explicit intersectional approach (i.e., how both racial and sexual identities influence behaviors or outcomes). For example, Hidalgo et al. (2013) examined how racial-ethnic-related discrimination and sexual identity–related discrimination were associated with HIV infection among sexual minority men. In another example, Stevens et al. (2013) focused on the “double minority status” of gay and transgender African Americans. Notably, these reports were published in the past 5 years, likely reflecting a growing recognition of the importance of within-group variability among sexual and gender minority populations (IOM, 2011). The results of the reports are presented in terms of whether the reports were comparative in nature (i.e., samples were racially-ethnically diverse) or were studies of SMYoC (i.e., samples were racially-ethnically homogenous).

Results from comparative samples

Reports that examined sexual health focused primarily on HIV/AIDS (e.g., prevalence, correlates, testing, care). In general, these reports indicate that, compared to White, non-Latino participants, SMYoC are more likely to be HIV positive (Celentano et al., 2005; Lemp et al., 1994; Valleroy et al., 2000), and Black SMY appear to be at greatest risk (Balaji, Bowles, Le, Paz-Bailey, & Oster, 2013). Reports also suggest that Latino and non-Latino SMYoC have riskier attitudes about sex and engage in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., unprotected sexual behavior, multiple partners) at higher levels compared to White, non-Latino gay and bisexual youth (Marsiglia, Nieri, Valdez, Gurrola, & Marrs, 2009; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). It is important to note, however, that other reports found no differences in sexual risk behavior by racial-ethnic group (Hipwell et al., 2013; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004; Solorio, Swendeman, & Rotheram-Borus, 2003) or found riskier sexual behaviors among White youth compared to young MSM of color (Harawa et al., 2004; Torres et al., 2013). Further, SMYoC shared that they experienced racial-ethnic discrimination or stereotypes in their sexual encounters (e.g., partner’s expectations of certain sexual behaviors because of their background; partner’s preferences for a particular background), but these experiences were not associated with more risky behavior (Hidalgo et al., 2013).

The literature also suggests that SMYoC lack adequate access to information about HIV/AIDS (Mustanski, Lyons, & Garcia, 2011; Voisin, Bird, Shiu, & Krieger, 2013) and are less likely to know their HIV status or follow up with appropriate medical care when compared to White, non-Latino SMY (Magnus et al., 2010). Notably, research on sexual health largely focused on risk; few reports included in our review focused on protective factors for risky sexual behaviors (e.g., stronger peer condom norms among Black youth; Bakeman & Peterson, 2007; social support among ethnically diverse samples; Seal et al., 2000). Yet there may also be racial-ethnic differences in effectiveness of interventions to reduce risky sexual behavior. For example, an intervention that combines case management, health care, and counseling with small group discussions was successful in temporarily decreasing unprotected anal intercourse among African American and White youth, but not Hispanic youth (Belden, Park, & Mince, 2008). This intervention also temporarily decreased unprotected oral intercourse for all groups, but this effect did not persist for African American youth after 6 months. Rotheram-Borus, Reid, and Rosario (1994) also found that an intervention consisting of one to 30 sessions about HIV facts, coping skills, health care access, barriers to safer sex, and prejudice against gays was effective at the 3-month assessment in decreasing unprotected sex acts among White, African American, and youth of other racial or ethnic groups, but not Hispanic youth. It is important to note that the number of sessions attended did not consistently decrease risky behavior for all groups, and the effectiveness differed at the time of assessment (e.g., 3 vs. 6 months).

Results from SMYoC samples

Reports that sampled only SMYoC frequently introduced and discussed culturally specific factors that are likely important in understanding health disparities across groups. For example, Black youth identified spirituality, family support, education, and LGBT organizations as factors that helped motivate and refocus their goals (Stevens et al., 2013). Another study found that school enrollment might be an important place to intervene for HIV risk and drug use for Black youth involved in house and ball culture (Traube, Holloway, Schrager, Smith, & Kipke, 2014). Clearly, more research is needed to understand the nuances of how culture, race-ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other relevant demographic factors (e.g., nativity) interact to inform sexual health and behavior.

Mental health

Over half of the 42 reports focused on mental health exclusively (n = 28; 67%) included sexual minority participants. In comparison to sexual health–focused studies, only eight reports (19%) sampled young MSM populations; thus, most of these studies focused on sexual identity rather than sexual behavior. Notably, only nine reports (21%) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group, and seven of these studies were focused on the experiences of Black or African American youth. The results are presented in terms of whether the reports were comparative in nature (i.e., samples were racially-ethnically diverse) or were studies of SMYoC (i.e., samples were racially-ethnically homogenous).

Results from comparative samples

The results for mental health in comparative reports across racial-ethnic groups were much more mixed than those for sexual health, suggesting that additional research is needed in this area in order to understand culturally relevant or demographic factors that may help to explain mental health disparities within SMY populations. Results from some reports indicated that Black and Latino youth experienced greater mental health problems (e.g., suicide behaviors, hopelessness) compared to White youth (Coffey, 2008; Glazier, 2009; Ryan et al., 2009; Seal et al., 2000). However, other reports found that White youth reported more mental health problems compared to youth of color (Burns, Ryan, Garofalo, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2015; LeVasseur, Kelvin, & Grosskopf, 2013; Poteat, Aragon, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009). Similarly, sexual minority young men who reported bullying had greater odds of suicidality than sexual minority young women, and this finding was stronger among non-Latino youth than among Latino youth (LeVasseur et al., 2013). Others found no differences by race-ethnicity in feelings of hopelessness or suicidality (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, 2009; Walls, Freedenthal, & Wisneski, 2008) or externalizing and internalizing symptoms (Marshal et al., 2013).

Results from SMYoC samples

Reports with mono-racial/ethnic samples did find evidence for poor mental health outcomes among SMYoC (Arias, 1998). Gender role strain may affect mental health, particularly among young Black MSM, because they may feel the need to be hypermasculine or risk being perceived as less than feminine (Fields et al., 2015). Black youth also reported more cumulative risk (i.e., accumulation of stressors that increase the likelihood of negative outcomes) than Latino youth, and cumulative risk is associated with increased suicide risk (Craig & McInroy, 2013). Thus, it appears critical to understand what cultural factors or learned coping mechanisms related to racism, for example, may protect SMYoC. Further, given that only a single report was identified that exclusively focused on mental health outcomes among Latino and Asian youth, respectively, more research is needed to understand the culturally relevant factors for these populations of SMYoC.

Substance use

Over half of the 42 reports focused on substance use exclusively (n = 29; 69%) included sexual minority participants, and 15 reports (36%) focused on the experiences of MSM. Only eight reports (19%) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group, and six of these reports focused on the experiences of African American or Black youth. The results described in this section largely come from the 29 reports of sexual minority youth that included or focused on race-ethnicity identification as a factor related to sexual health. Instead of discussing the reports in terms of racially-ethnically comparative versus homogenous sample designs, the results in this section are described by the type of substance investigated (i.e., smoking [n = 9], alcohol use [n = 25], and other drug use [n = 31]), given that discrepancies existed across type of substance, and prevention/intervention efforts likely differ depending on type of substance.

Smoking

Two comparative reports found that SMY from all racial-ethnic backgrounds had higher cigarette smoking prevalence compared to their respective heterosexual peers (i.e., Blosnich, Jarrett, & Horn, 2011; Corliss et al., 2014). However, there were racial-ethnic differences in types of smoking behaviors (e.g., Black youth had high prevalence of smoking cigars/clove cigarettes; Asian youth smoked less than their White peers; Blosnich, Jarrett, & Horn, 2011). Among high school students, Corliss and colleagues (2014) found that Black and Asian American/Pacific Islander SMY smoked more than White adolescents, suggesting that developmental period may be an important modifier of racial-ethnic disparities in smoking. Another report found that Native Hawaiian youth who were unsure of their sexual orientation reported more tobacco use than those who reported other sexual orientations (Glazier, 2009). In the same study, White bisexual youth reported more tobacco use than their White heterosexual peers. One report of Black and Latino gay and bisexual men found that marijuana use was associated with African American young men’s racial-ethnic identity (McKay, McDavitt, George, & Mutchler, 2012), suggesting the need for an intersectional approach in order to understand how culture interacts with sexual orientation to inform smoking behaviors.

Alcohol use

Comparative studies suggest there is either no racial-ethnic difference in the prevalence of alcohol use among LGB youth (Rosario et al., 1997; Warren et al., 2008) or that SMYoC have a lower prevalence of alcohol use (Newcomb et al., 2014). Further, some studies found that African American young MSM were (a) less likely than Whites to binge drink (Garofalo et al., 2010), (b) more likely to have unintentionally done something sexual because of alcohol or drug use (Warren et al., 2008), and (c) more likely to develop alcohol dependence or abuse (Burns et al., 2015). However, Latino YMSM demonstrated similar risks as Whites (e.g., binge drinking; Garafalo et al., 2010).

Factors associated with alcohol use among SMYoC include racism and antigay discrimination (Thoma & Huebner, 2013) and bullying and victimization (Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, et al., 2011). Bullying and victimization appear to be more strongly associated with alcohol use among Asian/Pacific Islander youth (Rosario et al., 2014). Yet there is evidence that family support is associated with less alcohol use over time across racial-ethnic groups (Newcomb, Heinz, & Mustanski, 2012), underscoring the importance of social support. Finally, alcohol may also be tied to social norms within a racial-ethnic group; for example, heavy alcohol use was tied to Latino gay men’s racial-ethnic identity (McKay, McDavitt, George, & Mutchler, 2012), again suggesting the need for culturally informed studies of alcohol use among SMYoC.

Illicit drug use

Notably, illicit drug use was often explored in the context of HIV risk (e.g., using drugs or alcohol before or during sexual encounters with casual partners; Balaji et al., 2013) or coping (e.g., self-medication; Magnus et al., 2010). Illicit drug use was rare or lower among Latino and Black youth compared to White youth (Celentano et al., 2005; Newcomb, Ryan, Greene, Garofalo, & Mustanski, 2014). One report found that youth of color generally reported lower prevalence of illicit drug use, although this difference was less pronounced among bisexual and unsure Black teenagers (Newcomb, Birkett, Corliss, & Mustanski, 2014).

Few studies examined illicit drug use among SMYoC using monoethnic samples. For example, one study that focused on Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) sexual minority youth found that the association between sexual minority status and substance use was not present in the teen years but emerged in the 20s (Hahm et al., 2008). Further, AAPI sexual minority young women might be at greater risk given the high prevalence of substance use compared to other AAPI groups. Among African American populations, illicit drugs are readily available in house and ball culture events (Stevens et al., 2013), and participation in house and ball culture was associated with greater use of illicit drugs (Traube et al., 2014).

Identity development

All but one of the 22 reports focused on mental health exclusively (n = 21; 95%) included sexual minority participants; four of the 22 studies focused on MSM populations. Over half of the reports (n = 13; 59%) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group (eight focused on African American or Black youth; four focused on Latino youth; and one focused on Asian youth). Findings from these studies are discussed in terms of the two most common themes: identity disclosure and development processes, and identity centrality.

Identity development and disclosure processes

The processes of identity disclosure (i.e., awareness, disclosure to family) and labels used appeared to be consistent across racial and ethnic groups (McInroy & Craig, 2012; Ryan et al., 2009), with the exception of unique terms that Black lesbians used to discuss identity (e.g., stemmes, studs; Reed, Miller, Valenti, & Timm, 2011; Timm, Reed, Miller, & Valenti, 2013). Few reports examined the experience of dual or multiple identity development exploration or resolution processes (e.g., Erikson, 1968). For example, one study found that White SMY were less likely than SMYoC to have a diffused sexual identity status (i.e., low in resolution, low in exploration; Hunter, 1996). Further, there were small correlations between racial-ethnic identity and sexual identity moratorium (i.e., low resolution, high exploration), diffused, and foreclosed statuses (i.e., high resolution, low exploration), respectively, but not achieved statuses (Hunter, 1996). Among Asian and Pacific Islander men, racial-ethnic identity affirmation (i.e., how positively or negatively one feels about their identity) was positively correlated with sexual identity affirmation (Vu, Choi, & Do, 2011). In addition, in one study, being committed to and feeling positive about one’s racial identity was associated with decreased internalized homophobia (Langdon, 2009).

To date, only one study has examined how racial-ethnic and sexual identities develop simultaneously (Jamil & Harper, 2010); youth in their study appeared to develop their racial-ethnic and sexual identities concurrently. It is important to note, however, that additional research does suggest the contexts and predictors of identity development may differ across racial-ethnic and sexual identity development. For example, whereas youth identified families as important for racial-ethnic identity development, community-based organizations and the Internet were important for sexual identity development (Jamil & Harper, 2010; Jamil, Harper, & Fernandez, 2009; Mustanski, Lyons, et al., 2011).

Important cultural constructs, such as machismo (i.e., strong sense of being manly) and familism (i.e., family needs take precedence over individual needs) for Latino youth, emerged when discussing the process of identity development (Yon-Leau & Munoz-Laboy, 2010). One report found that Latino youths’ sexual identity development was influenced by their exposure to machismo (Wilson et al., 2010). Latino youth also indicated that the identity development process was inherently relational because of the central role of family relationships in Mexican families (Yon-Leau & Munoz-Laboy, 2010). This was also found among Black MSM who described the perceived need to meet hypermasculine expectations for Black young men as heightened compared to White young men (Fields et al., 2015).

Identity centrality

Reports of identity centrality suggest that the salience of a particular identity largely depends on context (Arias, 1998; Robinson, 2010; Sanelli, 1998). For example, Latino youth who lived in predominately Latino-populated areas viewed their sexual orientation as more salient than their race-ethnicity in their identity (Adams, Cahill, & Ackerlind, 2005). Conversely, Vaught (2004) found that being Black did not allow for the salience of a gay identity because it was seen as only existent in White culture. Youth in another report, however, discussed the importance of understanding how the intersectionality of identities plays a role in lived experiences, like the overrepresentation of SMY and YoC in the juvenile justice system (Mountz, 2014).

Interpersonal relationships and contexts

Family

The majority of the 19 reports focused on family relationships (n = 16; 84%) sampled only sexual minority participants, and only one study focused on the experiences of young MSM populations. However, only seven reports (36%) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group (three focused on African American or Black youth; three focused on Latino youth; and one focused on Asian youth). The findings from these studies are discussed in terms of the two major themes that emerged: disclosure to family members and acceptance/rejection experienced from family related to sexual orientation.

Disclosure to family members

Several reports examining family relationships of SMYoC focused on the process of disclosing one’s sexual orientation to family members. One report found that Black and Latino youth were less likely than White youth to disclose their sexual orientation to their parents (Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011). Yet other reports have not found racial-ethnic differences in level of disclosure (Boxer, Cook, & Herdt, 1991; Ryan et al., 2009). Across all racial-ethnic groups, youths discussed fear of disclosure because of potential for rejection, and parental reactions to disclosure included both acceptance and rejection (Aleman, 2005; Balaji et al., 2012; Coffey, 2008; Follins, 2003; Hunter, 1990; Kuper, Coleman, & Mustanski, 2014; Munoz-Laboy et al., 2009; Reck, 2009; Timm et al., 2013; Voisin et al., 2013; Yon-Leau & Munoz-Laboy, 2010). Only one report found a significant difference in experienced parental acceptance after disclosure, in that Black participants reported less acceptance than Latino or White youth (Coffey, 2008).

Acceptance and rejection from family members

Eight reports examined parental support and rejection that were not specific to disclosure. Overwhelmingly, the results indicate few racial-ethnic differences in levels of perceived family support (Boxer et al., 1991; Mustanski, Newcomb, et al., 2011; Poteat, Mereish, DiGiovanni, & Koenig, 2011; Ryan et al., 2009); only one report found that White youth reported higher levels of parental support than SMYoC (Van Puymbroeck, 2001), and this difference was only significant for females. Other reports found that parental support was associated with more positive outcomes and reduced risk for all youth, regardless of race-ethnicity (Homma & Saewyc, 2007; Newcomb et al., 2012; Poteat et al., 2011).

School

The majority of the 10 reports focused on school experiences exclusively (n =6; 60%) included sexual minority participants, and none of the reports were focused on the experiences of MSM population. One-half of the reports (n = 5) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group (three focused on Latino youth; one focused on Asian youth; and one focused on Black youth). Findings from these reports are discussed in terms of school-related stressors and positive school experiences.

School stressors

School was largely examined as a source of stress (e.g., Jamil & Harper, 2010; Poteat et al., 2011). Homophobic victimization was associated with lowered school belonging, regardless of race-ethnicity, among SMY (Poteat et al., 2011). A recent study by Sterzing (2012), however, found that Black SMY were more likely to experience disciplinary actions at school compared to White, Latino, or multiracial youth. Another report found that among Asian American SMY, greater emotional distress was associated with more negative perceived school climates (Homma & Saewyc, 2007), but only among students with low self-esteem.

Positive school experiences

Many of the school-focused articles examined gay-straight alliances (GSAs). These reports documented that GSAs are largely composed of White participants (Garcia-Alonso, 2004; McCready, 2004) and may be less protective for YoC (Aleman, 2005). Thus, SMYoC may need to seek out different contexts within the school for different aspects of their identity (e.g., race-ethnicity-focused contexts for ethnic identity development; Jamil & Harper, 2010). To date, studies have not documented any racial-ethnic differences in attitudes about school, academic integration, or perceived academic or career barriers among SMY (Battle & Linville, 2006; Van Puymbroeck, 2001), but these studies are 10 to 15 years old and should be interpreted with caution.

Community

All but one of the 12 reports focused on community experiences exclusively (n = 11; 92%) included sexual minority participants, and only two focused on MSM populations. One-half of the reports (n = 6) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group (three focused on African American or Black youth, and three focused on Latino youth). In these reports, community-based organizations (CBOs) were viewed as a critical source of support for SMY (Arias, 1998; Gamarel, Walker, Rivera, & Golub, 2014; Jamil et al., 2009; Reck, 2009). Findings from racially-ethnically homogenous samples, however, demonstrate that these experiences may vary across subgroups of youth. For example, one report found that attachment to the LGBQ community did not reduce risk behaviors among Latino MSM (Agronick et al., 2004), whereas another report found that CBOs were helpful in mitigating the experiences of sexual harassment among Black lesbians (Reed & Valenti, 2012). Another study of Black female queer youth found that CBOs that focused on both ethnicity and sexuality helped foster agency and identity exploration in this population (Moench, 2012).

CBOs may not be perceived as accessible for all youth. For example, one study found that very few Black lesbian adolescents participated in CBOs (Follins, 2003), and another study found that Latino youth felt less comfortable at a medical clinic for HIV-seropositive MSM compared to Black youth (Magnus et al., 2010). Further, if YoC were not represented in CBOs, then SMYoC might have felt less comfortable in those contexts (Jamil & Harper, 2010). YoC also felt more comfortable in race-ethnicity-focused CBOs compared to CBOs focused on sexual orientation (Jamil & Harper, 2010). Compared to other youth, Black youth were more likely to endorse wanting support from other LGBQ adults in the community (Wells et al., 2013), but felt less attached to the LGBQ community compared to White and Latino youth (Warren et al., 2008).

Violence

The majority of the 20 reports focused on violence exclusively (n = 12; 60%) included sexual minority participants, and only two focused on MSM populations. Only four reports (20%) focused exclusively on one racial-ethnic group (two focused on African American or Black youth, and two focused on Latino youth). The findings from these reports are discussed in terms of violence specific to (a) only sexual orientation and (b) both sexual orientation and race-ethnicity.

Findings from reports focused on only sexual orientation–related bias

Across the contexts discussed in the preceding, a common theme that emerged was the experience of bias-related violence; however, the results are mixed in terms of whether (and how) youths’ experiences with sexual orientation–related violence differ by race-ethnicity. Two comparative reports found no racial-ethnic-group differences in levels of LGBQ-related victimization (Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, et al., 2011; Poteat et al., 2009), and no difference was found in a report that examined general bullying (Le Vasseuer et al., 2013). Yet three reports found that Black youth experience higher levels of LGBQ-related victimization compared to White or Latino youth (Garofalo, Mustanski, Johnson, & Emerson, 2010; Mustanski, Newcomb, et al., 2011; Vaught, 2004). Finally, one report found that Latino, Native American, and multiracial youth experienced higher levels of verbal and physical general bullying victimization compared to White and African American youth (Sterzing, 2012). Sexual orientation disparities in violence were also identified by Russell and colleagues (2014) for White, Hispanic, and Native American/Pacific Islander youth, but not for Black or Asian youth. Note that, in their report, Black youth had the highest rates of violence, while Asian youth had the lowest rates, regardless of sexual orientation.

Whether and how race-ethnicity modifies the relationship between victimization and outcomes is less clear. Two reports (Coffey, 2008; Newcomb et al., 2012) did not find any moderation by race-ethnicity. Three reports found that homophobic victimization was only associated with suicidality for White SMY (LeVasseur et al., 2013; Poteat et al., 2011). Further, Rosario et al. (2014) noted the important nuanced differences in the mediation of sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors by experiences of peer victimization by race-ethnicity.

Findings from reports focused on multiple types of violence

Findings were mixed in terms of whether youth reported more violence related to their sexual orientation or race-ethnicity and how strongly these different forms of violence contributed to health and well-being. Within-group reports found that Latino youth tended to report more harassment based on their sexual identity than based on their race-ethnicity (Adams et al., 2005; Aleman, 2005). A report of Black youth, however, found similar levels of harassment based on sexual identity and race (Follins, 2003). Further, among SMYoC, racial-ethnic oppression was experienced within the LGBQ community, whereas LGBQ-related oppression was experienced from the larger heterosexual community (Jamil et al., 2009).

In terms of how violence contributed to well-being, one report found that both LGBQ-related and racially motivated bullying were uniquely associated with depressive symptoms (Hightow-Weidman, Phillips et al., 2011). Thoma and Huebner (2013) found that there was an additive effect of racist and antigay discrimination on depression; however, antigay discrimination was only associated with suicide ideation whereas racist discrimination was only associated with substance use. Similarly, Garnett and colleagues (2014) found that youth who experienced multiple forms of bias had the highest odds of suicide ideation.

Discussion

Our review suggests that the extant research on SMYoC populations is mostly focused on sexual risk, substance use, and mental health problems rather than on normative developmental processes or positive youth development (e.g., promotive or protective assets or strengths). This finding is consistent with a recent study that comprehensively reviewed all National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded studies from 1989 to 2011 (Coulter et al., 2014) and found that only 0.5% of all NIH-funded studies focused on LGBQ populations, and they were largely focused on sexual health. This finding is also consistent with a prior content analysis of the literature of LGB people of color, which primarily focused on adults, and found that most empirical studies were guided by a risk perspective (Huang et al., 2009). The funding-research literature link is clear and problematic: the NIH, as well as other federal and private funding organizations, fund research that is often driven by a medical, problem-solving paradigm. This model requires that researchers examine the individual- and community-level risk factors that explain health disparities without explicit attention to structural-level factors that perpetuate risk (e.g., discrimination, stigma, oppression). Further, given a focus on pathology and risk, funding agencies rarely require that researchers examine resilience or normative, positive development.

The lack of attention to normative developmental processes is problematic because it undermines a comprehensive understanding of the lives of SMYoC and limits our scientific understanding to outcomes rather than the processes that contribute to those outcomes (see the integrative model for minority children of Coll et al., 1996). These results suggest a critical need for more culturally informed research on normative developmental processes and resilience among SMY, with attention to the unique and shared experiences of YoC. This implication is consistent with the substantial gap in the literature on prevention and protective factors for health outcomes of LGBQ populations, particularly among YoC (IOM, 2011), as well as the research focused on adolescence (Russell, 2016).

Research on the normative developmental process of identity development and interpersonal relationships in various contexts yielded very few differences by race-ethnicity. Differences that did exist were largely specific to processes of ethnic-racial identity development (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014) or ethnic-racial socialization (Hughes et al., 2006), such that these processes were salient for SMYoC and were associated with their sexual orientation development. Note that very few reports examined how these parallel processes developed simultaneously. Family relationships and reactions to disclosure of sexual orientation functioned similarly across race-ethnicity, suggesting that these processes are fairly universal. LGBQ spaces in schools (GSAs) or in the community (CBOs) also tended to promote well-being, regardless of race-ethnicity, for SMY. Further research, however, is needed to illuminate how to make those support spaces more welcoming to YoC, given that studies indicate low attendance by YoC. Further, given that bias related to race-ethnicity is frequently experienced from within the LGBQ community (Jamil et al., 2009), schools and CBOs that serve SMY should be cognizant of and address racism or ethnocentrism that is present in their programs. Finally, our review identified several limitations and areas of research that were underrepresented in the extant literature. We discuss these limitations in terms of (a) the sociodemographic profile of participants who were represented in the extant literature and (b) the conceptual approaches that were used to understand the lives of SMYoC.

Who is represented in studies of SMYoC?

Race–ethnicity

Although this review was focused on YoC broadly, the extant literature is not representative of the growing diversity of racial-ethnic groups in the United States. Asian and Latino populations are two of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Yet only five reports in our review focused exclusively on the experiences of Asian/Pacific Islander SMY, and only seven focused exclusively on Latino SMY. Given the changing demographic makeup of the United States, it is critical that future studies use purposive sampling methods to understand the experiences of these youth.

In addition, many of the reports in this review used pan-racial-ethnic labels (e.g., Asian, Latino) to identify youth, rather than youths’ country of origin. Given the importance of the broader political, economic, and social histories and experiences that various racial-ethnic groups hold in the United States, future research should examine potential within-group differences (e.g., Puerto Ricans, Mexicans). We acknowledge that studying these within-group differences is complicated and requires complex sampling and recruitment strategies. Nonetheless, these nuances are likely important for tailoring prevention programming aimed at reducing disparities and promoting positive development among these populations.

Gender

The majority of reports included in our review only sampled men; thus, the experiences of women and trans persons are largely invisible in the research. The few studies that did include men and women found gender moderation of the intersection of race-ethnicity and sexual minority status on adjustment (e.g., Ryan et al., 2009; Van Puymbroeck, 2001). More research is needed to understand how gender identity and expression intersect with race-ethnicity and sexual orientation to inform health and normative developmental processes.

Age

Most of the reports included in our review had participants who were in their 20s rather than in their teens. Given that youth are coming out at earlier ages (Saewyc, 2011), it is increasingly important that research capture the experiences of all SMY, not just those over the age of 18. Further, given that research documents that sexual orientation health disparities may be heightened in adolescence (Russell & Toomey, 2012), studies of early adolescents (ages 12–14) can help understand risk and resilience processes, particularly in the context of longitudinal studies spanning from early adolescence through young adulthood.

Intersectionality

Intersectional approaches (Bauer, 2014; Crenshaw, 1989) seek to understand disparities and marginalization processes by considering the strengths and challenges that individuals face because of their multiple social identities. Rather than examining one social category at a time, an intersectionality perspective examines how multiple social categories contribute collectively to the experiences of individuals (Cole, 2009; Frazier, 2012; Parent, DeBlaere, & Moradi, 2013). Research that is not approached from an intersectional lens ultimately contributes to intersectional invisibility (Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008) and a biased understanding of social categories. Notably, several of the reports in our review—especially those that were comparative in nature—did not intentionally focus on intersectionality, which may have resulted in fewer studies that directly assessed risk and resilience factors that may explain outcomes among YoC (e.g., racial-ethnic discrimination) or potential buffers of bias-based experiences (e.g., racial-ethnic identity). For example, a recent review clearly demonstrates that racial-ethnic identity developmental processes (e.g., affirmation, resolution, and exploration) are associated with positive adjustment (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Other research has demonstrated that sexual identity affirmation is meaningful for the well-being of sexual minorities (Ghavami, Fingerhut, Peplau, Grant, & Wittig, 2011). Yet only seven studies examined these co-occurring processes for SMYoC (Hidalgo et al., 2013; Hunter, 1996; Jamil & Harper, 2010; Kuper et al., 2014; Langdon, 2009; Stevens et al., 2013; Vu et al., 2011). Thus, research focused on SMYoC needs to attend to these normative co-occurring developmental processes, particularly during early adolescence (Herdt & McClintock, 2000).

Similarly, while overt experiences of bias were studied, microaggressions—or subtle, everyday experiences of mistreatment—were rarely discussed in the reports included in this review (for exceptions, see Mountz 2014; Voisin et al. 2013). Microaggressions based on race-ethnicity (e.g., assuming Asians are foreigners) and sexual orientation (e.g., using the word “gay” as a negative descriptor) are argued to be pervasive and more harmful than overt acts of discrimination because they are ambiguous (Sue, 2010). Specifically, targets of microaggressions may become distressed while trying to determine whether the particular encounter really was discriminatory (Solórzano, Ceja, & Yosso, 2000; Sue et al., 2007). Further, if the intent of the perpetrator is unclear (e.g., telling an SMY that they “doesn’t seem gay”), targets of microaggressions may question whether they are being oversensitive because of the ambiguous nature of microaggressions. Work that examines microaggressions among SMYoC would significantly contribute to current scholarship.

Limitations and conclusions

This analysis and review is not without limitations. First, the reports included in our review differed in terms of sample size, which makes comparisons across studies difficult at times. However, given that our goal was to be comprehensive, we did not want to value findings from large, quantitative studies over smaller, qualitative or mixed-methods studies by excluding reports with small sample sizes. Second, our review was limited to the published studies focused on SMYoC in the United States; thus, our findings are likely not generalizable to the broader population of SMYoC in the United States given the limitations of sampling, definitions of SMYoC, and methodologies used in the extant research. Future research is needed to understand how the intersection of sexual orientation and race-ethnicity contributes to health, well-being, and development in other contexts. Finally, given the structure of the extant literature, our review focused on broad racial-ethnic categories; as noted in the preceding, future research is needed to understand within- and between-group differences and similarities.

Given the relatively brief history of research on SMY, there are an impressive number of studies that have examined the experiences of SMYoC. Future research is needed to ensure that the diverse experiences of all SMYoC are captured in order to best inform future policy, program, and prevention and intervention efforts. In addition, while an examination of the intersection between race-ethnicity and sexual orientation is an important first step, it will be important for future studies to consider how other socially relevant characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status) explain risk and resilience among SMY populations.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

The first author’s time was supported by a National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Award (L60 MD008862). Writing support for the second author was supported by the California State University, Northridge Competition for Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity Award.

Footnotes

We use the phrase “youth of color” to be inclusive of all non-White, racial- and ethnic-minority youth.

References

- Adams EM, Cahill BJ, Ackerlind SJ. A qualitative study of Latino lesbian and gay youths’ experiences with discrimination and the career development process. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;66:199–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agronick G, O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Doval AS, Duran R, Vargo S. Sexual behaviors and risks among bisexually- and gay-identified young Latino men. AIDS & Behavior. 2004;8:185–197. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030249.11679.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman G. Doctoral dissertation. University of California–Los Angeles; Los Angeles, CA, USA: 2005. Voices from the margins: Experiences of racial and sexual identity construction for urban Latino youth. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias RA. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. California School of Professional Psychology; Alameda, CA, USA: 1998. The identity development, psychosocial stressors, and coping strategies of Latino gay/bisexual youth: A qualitative analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arrington-Sanders R, Leonard L, Brooks D, Celentano D, Ellen J. Older partner selection in young African-American men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:682–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Peterson JL. Do beliefs about HIV treatments affect peer norms and risky sexual behaviour among African-American men who have sex with men? International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2007;18:105–108. doi: 10.1258/095646207779949637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Bowles KE, Le BC, Paz-Bailey G, Oster AM. High HIV incidence and prevalence and associated factors among young MSM, 2008. AIDS. 2013;27:269–278. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835ad489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, Heffelfinger JD, Mena LA, Toledo CA. Role flexing: How community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2012;26:730–737. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes W, D’Angelo L, Yamazaki M, Belzer M, Schroeder S, Palmer-Castor J, Adolescent Trials Network HIV AIDS Identification of HIV-infected 12- to 24-year-old men and women in 15 US cities through venue-based testing. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:273–276. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle J, Linville D. Race, sexuality and schools: A quantitative assessment of intersectionality. Race, Gender & Class. 2006;13:180–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belden A, Park MJ, Mince J. Adolescents living safely: AIDS awareness, attitudes, and actions for gay, lesbian, and bisexual teens. In: Card JJ, Benner TA, editors. Model programs for adolescent sexual health: Evidence-based HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention interventions. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2008. pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich JR, Jarrett T, Horn K. Racial and ethnic differences in current use of cigarettes, cigars, and hookahs among lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:487–491. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Meyer I, Aranda F, Russell ST, Hughes T, Birkett M, Mustanski B. Mental health and suicidality among racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer AM, Cook JA, Herdt G. Double jeopardy: Identity transitions and parent— child relations among gay and lesbian youth. In: Cook JA, Herdt G, editors. Parent-child relations throughout life. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Stall R, Fata A, Campbell RT. Modeling minority stress effects on homelessness and health disparities among young men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health. 2014;91:568–580. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9876-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budwey S. Doctoral dissertation. Palo Alto University; Palo Alto, CA, USA: 2011. The sexual identity development of commercially sexually exploited youth. [Google Scholar]

- Burns MN, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Mental health disorders in young urban sexual minority men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card NA. Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Sifakis F, Hylton J, Torian LV, Guillin V, Koblin BA. Race/ethnic differences in HIV prevalence and risks among adolescent and young adult men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82:610–621. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection among young Black men who have sex with men-Jackson, Mississippi, 2006–2008. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaraman L, Woo M, Quach A, Erkut S. How have researchers studied multiracial populations? A content and methodological review of 20 years of research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20:336. doi: 10.1037/a0035437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Han CS, Hudes ES, Kegeles S. Unprotected sex and associated risk factors among young Asian and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2002;14:472–481. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.8.472.24114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerkin EM, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: The effect of race on risky sexual behavior among Black young men who have sex with men (YMSM) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34:237–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KA. Doctoral dissertation. University of Rochester; Rochester, NY, USA: 2008. Risk and protective factors for gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. [Google Scholar]

- Cohall A, Dini S, Nye A, Dye B, Neu N, Hyden C. HIV testing preferences among young men of color who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1961–1966. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL, Ortman JM. (Current Population Reports, P25-1143).Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf.

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64:170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi: 10.2307/1131600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolacion TB, Russell ST, Sue S. Sex, race/ethnicity, and romantic attractions: Multiple minority status adolescents and mental health. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:200–214. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Birkett MA, Newcomb ME, Buchting FO, Matthews AK. Sexual orientation disparities in adolescent cigarette smoking: Intersections with race/ethnicity, gender, and age. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1137–1147. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Kenst KS, Bowen DJ. Research funded by the National Institutes of Health on the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:e105–e112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, McInroy L. The relationship of cumulative stressors, chronic illness and abuse to the self-reported suicide risk of Black and Hispanic sexual minority youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;41:783–798. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;1989:139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Denning PH, Jones JL, Ward JW. Recent trends in the HIV epidemic in adolescent and young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 1997;16:374–379. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199712150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do TD, Hudes ES, Proctor K, Han CS, Choi KH. HIV testing trends and correlates among young Asian and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men in two U.S. cities. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2006;18:44–55. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorell CG, Sutton MY, Oster AM, Hardnett F, Thomas PE, Gaul ZJ, Heffelfinger JD. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in health care settings among young African American men who have sex with men: Implications for the HIV epidemic. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2011;25:657–664. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois SN, Emerson E, Mustanski B. Condom-related problems among a racially diverse sample of young men who have sex with men. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15:1342–1346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran T. Doctoral dissertation. 2008. Perceived influences of depression among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer adolescents: The role of race and ethnicity. Retrieved from Pro-Quest Dissertations & Theses Full Text. (1459058) [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre SL, Milbrath C, Peacock B. Romantic relationships trajectories of African American gay/bisexual adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;22:107–131. doi: 10.1177/0895904805298417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, Schuster MA. “I always felt I had to prove my manhood”: Homosexuality, masculinity, gender role strain, and HIV risk among young Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:122–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields SD, Wharton MJ, Marrero AI, Little A, Pannell K, Morgan JH. Internet chat rooms: Connecting with a new generation of young men of color at risk for HIV infection who have sex with other men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores SA, Bakeman R, Millett GA, Peterson JL. HIV risk among bisexually and homosexually active racially diverse young men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36:325–329. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181924201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follins LD. Doctoral dissertation. New York University; New York, NY, USA: 2003. To be young, different, and black: An exploratory study of the identity development process of black lesbian adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Forney JC, Miller RL. Risk and protective factors related to HIV-risk behavior: A comparison between HIV-positive and HIV-negative young men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2012;24:544–552. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier KE. Reclaiming the person: Intersectionality and dynamic social categories through a psychological lens. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2012;46:380–386. doi: 10.1007/s12124-012-9198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Walker JNJ, Rivera L, Golub SA. Identity safety and relational health in youth spaces: A needs assessment with LGBTQ youth of color. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2014;11:289–315. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2013.879464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alonso PM. Doctoral dissertation. University of Denver; Denver, CO, USA: 2004. From surviving to thriving: An investigation of the utility of support groups designed to address the special needs of sexual minority youth in public high schools. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett BR, Masyn KE, Austin SB, Miller M, Williams DR, Viswanath K. The intersectionality of discrimination attributes and bullying among youth: An applied latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1225–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Johnson A, Emerson E. Exploring factors that underlie racial/ethnic disparities in HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87:318–323. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey SJ, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami N, Fingerhut A, Peplau LA, Grant SK, Wittig MA. Testing a model of minority identity achievement, identity affirmation, and psychological well-being among ethnic minority and sexual minority individuals. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:79. doi: 10.1037/a0022532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazier RP. Doctoral dissertation. University of Northern Colorado; Greeley, CO, USA: 2009. Sexual minority youth and risk behaviors: Implications for the school environment. [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Wong FY, Huang ZJ, Ozonoff A, Lee J. Substance use among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders sexual minority adolescents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Figueroa RP. Sociodemographic characteristics explain differences in unprotected sexual behavior among young HIV-negative gay, bisexual, and other YMSM in New York City. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2013;27:181–190. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Walker F, Shah D, Belle E. Trends in HIV diagnoses and testing among U.S. adolescents and young adults. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:36–43. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9944-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall NM, Applewhite S. Masculine ideology, norms, and HIV prevention among young black men. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2013;12:384–403. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2013.781974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA, Johnson DF, Cochran SD, Cunningham WE, Valleroy LA. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35:526–536. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, McClintock M. The magical age of 10. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29:587–606. doi: 10.1023/A:1002006521067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick A, Kuhns L, Kinsky S, Johnson A, Garofalo R. Demographic, psychosocial, and contextual factors associated with sexual risk behaviors among young sexual minority women. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2013;19:345–355. doi: 10.1177/1078390313511328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo MA, Cotten C, Johnson AK, Kuhns LM, Garofalo R. “Yes, I am more than just that”: Gay/bisexual young men residing in the United States discuss the influence of minority stress on their sexual risk behavior prior to HIV infection. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2013;25:291–304. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2013.818086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Hurt CB, Phillips G, Jones K, Magnus M, Giordano TP, The YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group Transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance among young men of color who have sex with men: A multicenter cohort analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD, Smith JC. Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: Prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25:S39–S45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Outlaw AY, Wohl AR, Fields S, Hildalgo J, LeGrand S. Patterns of HIV disclosure and condom use among HIV-infected young racial/ethnic minority men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:360–368. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell A, Stepp SD, Keenan K, Allen A, Hoffmann A, Rottingen L, McAloon R. Examining links between sexual risk behaviors and dating violence involvement as a function of sexual orientation. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2013;26:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma Y, Saewyc EM. The emotional well-being of Asian-American sexual minority youth in school. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2007;3:67–78. doi: 10.1300/J463v03n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YP, Brewster M, Moradi B, Goodman M, Wiseman M, Martin A. Content analysis of literature about LGB people of color: 1998–2007. The Counseling Psychologist. 2009;38:363–396. doi: 10.1177/0011000009335255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. Violence against lesbian and gay male youths. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1990;5:295–300. doi: 10.1177/088626090005003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. Doctoral dissertation. City University of New York; New York, NY, USA: 1996. Emerging from the shadows: Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Personal identity achievement, coming out, and sexual risk behaviors. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Discrimination hurts: The academic, psychological, and physical well being of adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:916–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00670.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institutes of Medicine [IOM] The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil OB, Harper GW. School for the self: Examining the role of educational settings in identity development among gay, bisexual, and questioning male youth of color. In: Bertram CC, Crowley SM, Massey SG, editors. Beyond progress and marginalization: LGBTQ youth in educational contexts adolescent cultures, school and society. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2010. pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil OB, Harper GW, Fernandez MI. Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay–bisexual–questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0014795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Ivory AH. A forgotten sexuality: Content analysis of bisexuality in the medical literature over two decades. Journal of Bisexuality. 2012;12:35–48. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2012.645701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MH, Hsu L, Wong E, Liska S, Anderson L, Janssen RS. Seroprevalence of and risk factors for hepatitis A infection among young homosexual and bisexual men. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1997;175:1225–1229. doi: 10.1086/593675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Torian LV, Guilin V, Ren L, MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA. High prevalence of HIV infection among young men who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS. 2000;14:1793–1800. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, Coleman BR, Mustanski BS. Coping with LGBT and racial–ethnic-related stressors: A mixed-methods study of LGBT youth of color. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24:703–719. doi: 10.1111/jora.12079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon YN. Doctoral dissertation. Howard University; Washington, DC, USA: 2009. Predictors and correlates associated with the influence of spiritual coping on identity development of African American gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Lemp GF, Hirozawa AM, Givertz D, Nieri GN, Anderson L, Lindegren ML, Katz M. Seroprevalence of HIV and risk behaviors among young homosexual and bisexual men. The San Francisco/Berkeley Young Men’s Survey. JAMA. 1994;272:449–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520060049031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVasseur MT, Kelvin EA, Grosskopf NA. Intersecting identities and the association between bullying and suicide attempt among New York city youths: Results from the 2009 New York City youth risk behavior survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:1082–1089. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2012.300994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F, Stone DM, Tharp AT. Physical dating violence victimization among sexual minority youth. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:e66–e73. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2014.302051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus M, Jones K, Phillips G, Binson D, Hightow-Weidman LB, Richards-Clarke C, YMSM of Color Special Projects of National Signficance Initiative Study Group Characteristics associated with retention among African American and Latino adolescent HIV-positive men: Results from the outreach, care, and prevention to engage HIV-seropositive young MSM of color special project of national significance initiative. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2010;53:529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b56404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dermody SS, Shultz ML, Sucato GS, Stepp SD, Chung T, Hipwell AE. Mental health and substance use disparities among urban adolescent lesbian and bisexual girls. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2013;19:271–279. doi: 10.1177/1078390313503552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Nieri T, Valdez E, Gurrola M, Marrs C. History of violence as a predictor of HIV risk among multiethnic, urban youth in the Southwest. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2009;8:144–165. doi: 10.1080/15381500903025589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J, Hosek SG. An exploration of the down-low identity: Nongay-identified young African-American men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:1103–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCready LT. Some challenges facing queer youth programs in urban high schools: Racial segregation and de-normalizing Whiteness. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education. 2004;1:37–51. doi: 10.1300/J367v01n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McInroy L, Craig SL. Articulating identities: Language and practice with multiethnic sexual minority youth. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2012;25:137–149. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2012.674685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKay TA, McDavitt B, George S, Mutchler MG. ‘Their type of drugs’: Perceptions of substance use, sex and social boundaries among young African American and Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14:1183–1196. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.720033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL, Reed SJ, McNall MA, Forney JC. The effect of trauma on recent inconsistent condom use among young Black gay and bisexual men. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2013;12:349–367. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2012.749820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moench C. Doctoral dissertation. Wayne State University; Detroit, MI, USA: 2012. Queer adolescent girls use of out-of school literacy events to semiotically express understanding of their gender and sexual identity in order to enhance personal agency in their lives. [Google Scholar]

- Mountz SE. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Washington; Seattle, WA, USA: 2014. Overrepresented, underserved: The experiences of LGBTQ youth in girls detention facilities in New York state. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Laboy M, Leau CJY, Sriram V, Weinstein HJ, del Aquila EV, Parker R. Bisexual desire and familism: Latino/a bisexual young men and women in New York City. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2009;11:331–344. doi: 10.1080/13691050802710634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Lyons T, Garcia SC. Internet use and sexual health of young men who have sex with men: A mixed-methods study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9596-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Newcomb ME, Garofalo R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A developmental resiliency perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: The Quarterly Journal of Community & Clinical Practice. 2011;23:204–225. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.561474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler MG. Seeking sexual lives: Gay youth and masculinity tensions. In: Nardi P, editor. Research on men and masculinities series: Gay masculinities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Birkett M, Corliss HL, Mustanski B. Sexual orientation, gender, and racial differences in illicit drug use in a sample of US high school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:304–310. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Mustanski B. Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: A longitudinal multilevel analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:783–793. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Greene GJ, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Prevalence and patterns of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use in young men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;141:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster AM, Dorell CG, Mena LA, Thomas PE, Toledo CA, Heffelfinger JD. HIV risk among young African American men who have sex with men: A case–control study in Mississippi. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:137–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster AM, Wejnert C, Mena LA, Elmore K, Fisher H, Heffelfinger JD. Network analysis among HIV-infected young Black men who have sex with men demonstrates high connectedness around few venues. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013;40:206–212. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182840373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw AY, Phillips G, Hightow-Weidman LB, Fields SD, Hidalgo J, Halpern-Felsher B, Green-Jones M. Age of MSM sexual debut and risk factors: Results from a multisite study of racial/ethnic minority YMSM living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25:S23–S29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC, DeBlaere C, Moradi B. Approaches to research on intersectionality: Perspectives on gender, LGBT, and racial/ethnic identities. Sex Roles. 2013;68:639–645. doi: 10.1007/s11199-013-0283-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]