Abstract

We describe a patient who developed progressive weakness in all limbs without sensory symptoms 4 weeks after upper respiratory system infection. Electrophysiological findings suggested a new variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome named “acute motor conduction block neuropathy”. Electrophysiological studies were performed at admission, 12th and 28th weeks. At the 28th week, the clinical examination and electrophysiological findings showed complete recovery.

Keywords: Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute motor conduction block neuropathy, conduction block, acute motor neuropathy, IVIg treatment

Abstract

Olgumuz üst solunum sistemi enfeksiyonundan 4 hafta sonra gelişen, duyu bozukluğu olmaksızın progresif seyirli dört ekstremite güçsüzlüğü ile prezente olmuştur. Elektrofizyolojik bulgular nadir bir Guillain-Barre sendromu varyantı olan “akut motor iletim bloğu nöropatisi” ile uyumlu bulunmuştur. Elektrofizyolojik çalışmalar 12. ve 28. haftada tekrar edildi. 28. haftada hastanın klinik ve elektrofizyolojik bulguları tamamen düzelmiş olarak bulundu.

Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an autoimmune disorder encompassing a heterogeneous group of pathological and clinical entities. However, the precise mechanism of the immunologic injury is unclear. Approximately 50% to 70% of patients have a history of an acute illness within 4 weeks prior to GBS. Often this illness is an upper respiratory disease or gastroenteritis. Specific agents that have been implicated include cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and Campylobacter jejuni. C. jejuni is one of the most common cause of diarrheal illness. Recently, it has been shown that a previous gastrointestinal infection with C. jejuni is associated with a more severe form of GBS (1).

Several subtypes of GBS have been classified according to clinical, electrophysiological, and pathological findings along with preceding infections and immunization and presence of specific antibodies (1). A new variant of GBS named “acute motor conduction block neuropathy” (AMCBN) has been proposed recently with a report of two cases (2). AMCBNs are characterized by acute symmetric motor neuropathy with early conduction block (CB) in intermediate and distal nerve segments. Herein, we report the clinical, immunologic, and serial electrophysiological findings in a 48-year-old patient diagnosed with AMCBN.

Case

A 48-year-old man developed progressive weakness in all limbs without sensory symptoms 4 weeks after an upper respiratory tract infection. At admission, four weeks after initial onset of symptoms, neurological examination revealed decreased strength bilaterally and symmetrically in the proximal and distal muscles of the upper and lower limbs (Medical Research Council [MRC] score 4 in proximal muscles and 5 in distal muscles). The patient had difficulty walking on heels and on toes and, his sensation to light touch and pinprick was normal. Vibration sensation diminished minimally in the lower limbs and tendon reflexes were abolished. Cranial nerves and autonomic functions were intact. Cerebrospinal fluid examination showed increased protein level (1.51 g/L) with negative cell count. Stool culture and serologic test results were negative and did not support a recent Campylobacter jejuni infection. The titers for IgG anti-GD1a and IgG anti-GM1 antibodies were not elevated. Cranial and cervical MRIs were normal. Electrophysiological studies were performed at admission (4th week), and repeated at 12th and 28th weeks after the onset of initial symptoms (Table 1). The first examination revealed partial motor conduction block in the wrist-elbow segments of both median nerves and the knee-ankle segment of right tibial nerve (Figure 1a-b-c). Motor conduction velocities were slightly reduced in the wrist-elbow segments of both median nerves, but they were normal in the ulnar, peroneal and tibial nerves bilaterally. Amplitudes of the distal compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and distal motor latencies (DMLs) were normal. F-waves were absent in the median nerve bilaterally. Orthodromic sensory nerve conduction studies of both the median and ulnar nerves and antidromic sensory nerve conduction studies in both sural nerves were also normal. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) after both tibial nerves stimulations were normal. Electromyography (EMG) showed a variable reduced recruitment pattern with high-frequency discharging motor units at the upper limbs (biceps brachii and abductor pollicis brevis) and lower limbs (tibialis anterior and vastus lateralis), but no spontaneous activity was detected.

Table 1.

Electrophysiological findings of the patient who had acute motor neuropathy with conduction blocks at admission (4th week), 12th and 28th weeks

| 4th week | 12th week | 28th week | normal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | limits | |

| Median nerve distal latency (ms) | 2.9 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 3.0 | <3.8 |

| CMAP amplitude thenar/forearm (mV) | 7.9/2.1 | 6.3/3.0 | 7.6/2.9 | 5.9/2.7 | 8.9/7.0 | 6.5/4.4 | >4.3 |

| CB | CB | CB | CB | ||||

| conduction velocity, forearm (m/s) | 48.2 | 47.3 | 53.8 | 52.0 | 51.0 | 50.0 | >49.7 |

| Median nerve SNAP amplitude (2nd F-W) (mV) | 9.3 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 10 | NA | >9.3 |

| conduction velocity (m/s) | 50 | 54.5 | 59.5 | 66.3 | 50.0 | NA | >39.4 |

| Ulnar nerve distal latency (m/s) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | NA | NA | <3.3 |

| motor nerve conduction amplitude hypothenar/forearm (mV) | 5.0/3.2 | 6.4/4.0 | 5.6/3.0 | 7.2/4.9 | NA | NA | >7.0 |

| conduction velocity, forearm (m/s) | 51.2 | 59.5 | 57.9 | 56.1 | NA | NA | >49.9 |

| Ulnar nerve SNAP amplitude (5th F-W) (mV) | 7.1 | NA | 7.0 | 11.0 | NA | NA | >7.0 |

| conduction velocity (m/s) | 50.5 | NA | 65.3 | 59.2 | NA | NA | >37.3 |

| Peroneal nerve distal latency (ms) | 4.7 | 4.0 | 4.5 | NA | NA | NA | <5.8 |

| CMAP amplitude (EDB/leg) (mV) | 4.1/3.4 | 7.2/5.5 | 2.7/2.4 | NA | NA | NA | <3.6 |

| conduction velocity (m/s) | 43.9 | 50.0 | 47.2 | NA | NA | NA | >40.9 |

| Tibial nerve distal latency (ms) | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.8 | NA | 5.2 | NA | <5.8 |

| CMAP amplitude (AHB/leg) (mV) | 6.2/2.7 | 4.3/2.5 | 11.4/4.9 | NA | 11.4/8.4 | NA | >3.6 |

| CB | CB | ||||||

| conduction velocity (m/s) | 40.2 | 39.9 | 46.5 | NA | 45.6 | NA | >39.6 |

| Sural nerve SNAP amplitude (mV) | 5.0 | 5.8 | 5.4 | NA | NA | NA | >5.0 |

| conduction velocity (m/s) | 37.0 | 36.0 | 35.4 | NA | NA | NA | >33.8 |

CB: conduction block, NA: not avaible, 2nd F-W: second finger-wrist, 5thF-W: fifth finger-wrist, EDB: extansor digitorum brevis, AHB: abductor hallusis brevis, CMAP: Compound muscle action potential, SNAP: Sensory nerve action potential

Figure 1.

a) Partial motor conduction block in the wrist-elbow segment of right median nerve at 4th week. b) Partial motor conduction block in the wrist-elbow segment of left median nerve at 4th week. c) Partial motor conduction block in the the knee-ankle segment of right tibial nerve at 4th week

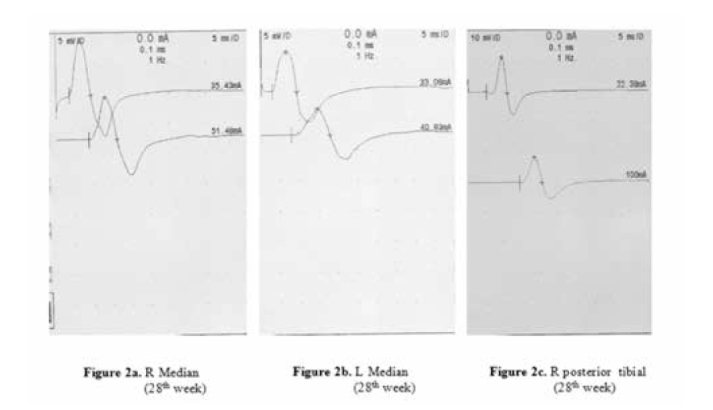

The patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) (.4 g/kg/day for 5 days). Eight weeks after the treatment, a slight improvement of strength was observed in the upper limbs, but electrophysiological examination did not show any change. At the 28th week, clinical examination and electrophysiological findings showed complete recovery of the upper and lower limbs (Figure 2a-b-c).

Figure 2.

a) Normal motor conduction study in the wrist-elbow segment of right median nerve at 28th week. b) Normal motor conduction study in the wrist-elbow segment of left median nerve at 28th week. c) Normal motor conduction study in the the knee-ankle segment of right tibial nerve at 28th week

Discussion

The patient reported here developed acute symmetric weakness in the upper and lower limbs. Electrophysiological studies showed motor CB’s in both the median nerves and the right tibial nerve (3,4) No clinical and electrophysiological evidence of sensory involvement was detected. According to these data, our patient could not be classified into any of the well-known subtypes of GBS, because he neither showed demyelinating or axonal features, nor cranial nerve involvement. Serial electrophysiological studies in the patient showed that abnormal area reduction of CMAPs was the result of partial CB.

In Western countries, motor-sensory GBS is considered as the most frequent clinical variety. Capasso et al. shown that sensory deficit may be difficult to demonstrate early in the disease. But 61% of patients have some electrophysiological evidence of sensory nerve involvement such as low amplitude or absent sensory potentials. As well as, electrophysiological evidence of sensory nerve involvement in one nerve seen in up to 80% of patients during the disease (2,5). As a matter of fact, SEP performed in the early phase of the disease demonstrated proximal conduction slowing, whereas distal sensory conductions were commonly normal in a high percentage of patients (2). In our patient, clinical and electrophysiological evidence of sensory involvement was not observed and SEP was normal. For this reason, we considered pure motor neuropathy in our patient.

Areflexia is the important finding for the diagnosis of GBS. The protected deep tendon reflexes in the patients with acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) may be an indicator of good clinical outcome (6). Some patients with AMAN showed hyperreflexia in the recovery phase. Our patient had hyporeflexia throughout the disease course.

Lefaucheur et al. described four patients who presented with asymmetric pure motor deficit and persistent multifocal motor conduction blocks (7). There was diffuse areflexia, but little or no sensory disturbance was the clinical picture. Cerebrospinal fluid contained normal or mildly increased protein levels without cells. Anti-ganglioside antibodies were positive in three patients. Intravenous immunoglobulins given to the patients for five days. This treatment produced nearly complete symptom resolution in three patients and was ineffective in one patient. Because of persistence of multifocal motor conduction blocks for several months as the isolated electrophysiological feature, these cases could not be consistent with GBS or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) (7).

It has been shown that, muscle weakness has been correlated with an antibody-mediated primary axonal degeneration in acute motor axonal neuropathy (8). Conduction block that recovers without development of increased temporal dispersion or other demyelinating features. However in some patients with antiganglioside antibodies a physiologic conduction block at the axolemma of the Ranvier node has been described. The severity of axonal damage may vary from reversible functional impairment of nodal axolemma to complete axonal damage with subsequent Wallerian degeneration. The current electrophysiologic criteria are not able to distinguish with certainty different subtypes in early GBS (2,8). Multiple electrophysiologic studies are required for identification of GBS subtypes and to explain the pathophysiologic mechanisms of muscle weakness (8).

In our case, the clinical findings were symmetric and titers of IgG anti-GD1a and IgG anti-GM1 were not elevated. Electrophysiological findings, especially motor CBs, showed complete recovery at the 28th week. For these reasons, we did not consider multifocal motor neuropathy in our patient. Instead, our case resembles that reported by Capasso et al. who has described two patients affected by AMCBN with a complete clinical and electrophysiological recovery within 6 weeks (2). However, our patient required longer period to improve both clinically and electrophysiologically. The slow recovery cannot be explained by an axonal degeneration process, since EMG never showed spontaneous activity. The patients reported by Capasso et al. were treated early, while in our patient the treatment started when the clinical picture was completely developed. Treatment delay in our patient may explain the slow recovery. The pathologic basis of CB is thought to be conduction failure due to block and disruption of sodium channels at the Ranvier nodes (2,9). There was not an acute demyelization in our patient, because recovery from demyelinating CB is characterized by increased duration of CMAP (temporal dispersion) and slowing of conduction velocity. In our case, the recovery of CB was without temporal dispersion and slowing conduction velocity. It has been suggested that reversible conduction failure constitutes the pathophysiological mechanism in IgG anti GM1-positive patients with AMAN. Anti-GM1 antibodies bind to the axolemma at the Ranvier nodes and may induce reversible conduction failure, possibly depending on the intensity of local immune reaction, or to complement deposition (10,11). In our patient, anti-GM1 antibodies were not elevated, but we think that another immune reaction may induce reversible conduction failure.

It has been suggested that AMBCN may represent an “arrested” AMAN. The intensity of local immune reaction may induce reversible conduction failure or axonal degeneration (2). If the autoimmune attack is limited in time and extension, the nodal function may rapidly recover and no axonal degeneration occurs. In our patient, we did not find any sign of axonal degeneration until the complete clinical resolution, even though the severe clinical picture suggests an aggressive immune attack on peripheral nerves. The clinical picture of our patient was completely developed after IVIg treatment. For these reason, we did not consider AMAN.

To conclude, we assume that AMCBN represents a variant of GBS, distinct from AMAN. Clinical severity, disease duration, and long-term clinical and electrophysiological follow-up of patients will provide further evidence that AMCBN should be considered as a distinct entity from AMAN. Serial electrophysiological studies will be helpful for proper classification of the patients and are necessary for accurate diagnosis and for establishing the prognosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors reported no conflict of interest related to this article.

Çıkar çatışması: Yazarlar bu makale ile ilgili olarak herhangi bir çıkar çatışması bildirmemişlerdir.

References

- 1.Hughes RA, Cornblath DR. Guillain-Barre syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:1653–1666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capasso M, Caporale CM, Pomilio F, Gandolfi P, Lugaresi A, Uncini A. Acute motor conduction block neuropathy. Another Guillain-Barre syndrome variant. Neurology. 2003;61:617–622. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh SJ, Kim DE, Kuruoglu HR. What is the best diagnostic index of conduction block and temporal dispersion? Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:489–493. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of partial conduction block. Muscle Nerve. 1999;8:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon PH, Wilbourn AJ. Early electrodiagnostic findings in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:913–917. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajabally YA, Strens LHA, Abbott RJ. Acute motor conduction block neuropathy followed by axonal degeneration and poor recovery. Neurology. 2006;66:287–288. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194305.04983.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefaucheur JP, Gregson NA, Gray I, von Raison F, Bertocchi M, Creange A. A variant of multifocal neuropathy with acute, generalised presentation and persistent conduction blocks. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1555–1561. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uncini A, Yuki N. Electrophysiologic and immunopathologic correlates in Guillain-Barré syndrome subtypes. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009 Jun;9:869–84. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manganelli F, Pisciotta C, Iodice R, Calandro S, Dubbioso R, Ranieri A, Santoro L. Case of acute motor conduction block neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:224–226. doi: 10.1002/mus.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuki N, Taki T, Inagaki F, Kasama T, Takahashi M, Saito K, Handa S, Miyatake T. A bacterium lipopolysaccharide that elicits Guillain Barre syndrome has a GM1 ganglioside-like structure. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1771–1775. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White JR, Sachs GM, Gilchrist JM. Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block and Campylobacter jejuni. Neurology. 1996;46:562–563. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]