Abstract

Background

Recent epidemiological studies indicate that only 30–50% of undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients are identified using glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and elevated fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels. Thus, novel biomarkers for early diagnosis and prognosis are urgently needed for providing early and personalized treatment.

Methods

Here, we studied the glycation degrees of 27 glycation sites representing nine plasma proteins in 48 newly diagnosed male T2DM patients and 48 non-diabetic men matched for age (range 35–65 years). Samples were digested with trypsin and enriched for glycated peptides using boronic acid affinity chromatography. Quantification relied on mass spectrometry (multiple reaction monitoring) using isotope-labelled peptides as internal standard.

Results

The combination of glycated lysine-141 of haptoglobin (HP K141) and HbA1c provided a sensitivity of 94%, a specificity of 98%, and an accuracy of 96% to identify T2DM. A set of 15 features considering three glycation sites in human serum albumin, HP K141, and 11 routine laboratory measures of T2DM, metabolic syndrome, obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance provided a sensitivity of 98%, a specificity of 100%, and an accuracy of 99% for newly diagnosed T2DM patients.

Conclusions

Our studies demonstrated the great potential of glycation sites in plasma proteins providing an additional diagnostic tool for T2DM and elucidating that the combination of these sites with HbA1c and FPG could improve the diagnosis of T2DM.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12014-017-9145-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biomarker, Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), Glycation sites, HbA1c, Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), Plasma proteins, Protein glycation, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) refers to a group of metabolic disorders characterized by elevated blood glucose concentrations. The majority (90–95%) of DM patients have type 2 DM (T2DM), which is characterized by peripheral insulin resistance and an inability of pancreatic beta cells to compensate for that by increasing insulin secretion [1]. Current diagnostic criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO) for the diagnosis of T2DM include glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol)), elevated fasting plasma glucose (FPG) concentrations (FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L) and/or plasma glucose concentrations 2 h after a 75 g oral glucose load (≥11.1 mmol/L) in the context of a standardized oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) [2, 3]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) defines a HbA1c level of ≥6.5% or a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of ≥126 mg/dL (≥7 mmol/L) or 2-h plasma glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L) during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or a random plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L) as equally valid diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes [1]. However, epidemiological studies revealed that compared to OGTT glucose values the use of either HbA1c or FPG only identifies ~30–50% of previously undiagnosed T2DM patients [4–8]. Moreover, categories of increased risk for diabetes (prediabetes) include a HbA1c level of 5.7–6.4% or a FPG level between 100 and 125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L) or 2-h plasma glucose level between 140 and 199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L) in the OGTT [1]. For the distinction of patients with prediabetes, HbA1c values have also been shown to be less sensitive compared to FPG and 2 h OGTT glucose [7]. HbA1c also plays a critical role in the management of diabetic patients, as it reflects the average plasma glucose level for the preceding 3-month period and correlates well with micro- and macrovascular complications [4–6]. FPG is the preferred diagnostic parameter, because it is simple, inexpensive, relatively risk-free, and correlates with diabetic complications like retinopathy [7]. However, even using longitudinally measured HbA1c levels, the prediction or retrospective attribution of individual T2DM associated complications or mortality are not possible with this parameter of chronic hyperglycemia [8–12]. Therefore, there is an unmet need to better predict the individual chronic hyperglycemia-related diabetes outcomes.

Glycated proteins, such as hemoglobin in erythrocytes and serum albumin as major plasma protein, are recognized as markers of hyperglycemia due to the high sensitivity towards even slightly elevated plasma glucose levels [13, 14]. However, only methods determining global protein glycation degrees have been established, whereas recent evidence suggests specific glycation sites in plasma proteins as potential biomarkers for early diagnoses of DM [14–17]. In contrast to the long half-life time of hemoglobin in erythrocytes, plasma proteins vary in half-life times from hours to several weeks, which might allow selecting a small set of protein glycation sites resembling more closely short to medium term fluctuations of plasma glucose levels.

Here we quantified 27 glycation sites in nine plasma proteins after tryptic digestion by mass spectrometry and evaluated their diagnostic value alone and in combination with current WHO criteria of HbA1c and FPG levels. Selection of glycation sites relied on a list of 52 candidates we previously identified and studied [17], by judging each for the biomarker potential and ease of peptide synthesis. A single-blind study using plasma samples from 48 newly diagnosed T2DM patients and 48 non-diabetic individuals clearly indicated different glycation degrees characteristic of each glycation site with glycated Lys141 of haptoglobin providing the best sensitivities (~94 and ~78%) and specificity (~98%) when combined with HbA1c and FPG levels, respectively.

Methods

Blood samples

Blood samples were obtained from 48 newly diagnosed male T2DM patients and 48 non-diabetic men matched for age (range 35–65 years) in the context of a study of parameters of insulin resistance (Additional file 1: Table S1). Anthropometric and laboratory chemistry parameters were measured or calculated as previously described [18, 19]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universität Leipzig (approval no: 159-12-21052012), and performed in accordance to the declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave written informed consent before taking part in this study. In our study, we defined individuals with T2DM according to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association [1]:

A HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher, or

A fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L) or higher (fasting was defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 h), or

A 2-h plasma glucose level of 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) or higher during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or

A random plasma glucose of 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) or higher in a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia (i.e., polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss) or hyperglycemic crisis

The group of T2DM patients has been further categorized into those with HbA1c levels patients below (n = 23) and equal or higher than 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) (n = 25). For those patients with HbA1c < 6.5% (48 mmol/mol), the diagnosis of T2DM has been established on the basis of repeated measurements of fasting plasma glucose (>7.0 mmol/L) or 2 h oral glucose tolerance test glucose concentrations >11.1 mmol/L [1]. Since patients were newly diagnosed, none of the individuals in the T2DM receive anti-hyperglycemic medication. All men had a body mass index (BMI) larger than 25.0 kg/m2 and were grouped in overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2; 15 without and 10 with T2DM) and obese individuals (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). EDTA blood samples were collected between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. after a 12-h fasting period, centrifuged (500×g, 5 min) and analyzed within 1 h after blood drawing for routine laboratory parameters or stored at −80 °C after the cell debris was removed by filtration (Rotilabo® syringe filter) for the analyses of the glycation sites. Plasma insulin and proinsulin were measured with an enzyme immunometric assay for the IMMULITE automated analyzer (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Serum high-sensitive CRP (C-reactive protein) was measured by immunonephelometry (Dade-Behring, Milan, Italy). HbA1c, plasma glucose, serum total- high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids were measured as previously described [18].

Peptide quantification

Glycation sites previously identified in plasma samples of patients with diabetes [17] were quantified by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI–MS) on a QTRAP 4000 (AB Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany) coupled on-line to reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using timed multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Briefly, small molecules and peptides were removed from plasma by ultrafiltration (5 kDa cut-off). The concentrated sample was digested with trypsin (37 °C, 18 h, 5% w/w), spiked with a concentration-balanced mixture of 13C,15N-labelled glycated peptides as internal standard, enriched for glycated peptides by boronic acid affinity chromatography (BAC), and desalted by solid phase extraction (SPE) using optimized protocols [15, 20–22]. The internal standard was added after tryptic digestion to provide the highest accuracy by compensating variations, such as nonspecific degradation, during sample preparation [23], especially as trypsin could cleave some standard peptides at Lys/Arg-Pro-motifs or glycated residues.

Table 1.

Glycated peptides of different plasma proteins quantified in tryptic digests of type 2 diabetes and control plasma samples

| # | Sequence | Protein symbol (Accession number, glycation site) | t R (min) | Q1 m/z (±0.2) | Q3 m/z (±0.2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TCVADESAENCDKSLHTLFGDK | HSA (P02768; K64) | 13.8 | 887.1 | 869.1 |

| 2 | SLHTLFGDKLCTVATLR | HSA (P02768, K73) | 17.9 | 698.7 | 680.7 |

| 3 | ETYGEMADCCAKQEPER | HSA (P02768, K93) | 8.8 | 746.0 | 136.1 |

| 4 | ETYGEMADCCAKQEPER | HSA (P02768, K93) | 7.9 | 751.3 | 136.1 |

| 5 | AAFTECCQAADKAACLLPK | HSA (P02768, K174) | 15.9 | 763.0 | 120.0 |

| 6 | AACLLPKLDELRDEGK | HSA (P02768, K181) | 16.2 | 664.0 | 646.0 |

| 7 | AEFAEVSKLVTDLTK | HSA (P02768, K233) | 18.6 | 907.0 | 880.0 |

| 8 | ADLAKYICENQDSISSK | HSA (P02768, K262) | 13.6 | 1052.5 | 1025.5 |

| 9 | TYETTLEKCCAAADPHECYAK | HSA (P02768, K359) | 9.9 | 670.8 | 237.1 |

| 10 | VFDEFKPLVEEPQNLIK | HSA (P02768, K378) | 18.6 | 1104.1 | 1077.1 |

| 11 | KVPQVSTPTLVEVSR | HSA (P02768, K414) | 14.9 | 601.3 | 900.5 |

| 12 | KQTALVELVK | HSA (P02768, K525) | 13.1 | 645.9 | 603.9 |

| 13 | EQLKAVMDDFAAFVEK | HSA (P02768, K545) | 18.7 | 668.3 | 120.1 |

| 14 | KLVAASQAALGL | HSA (P02768, K574) | 16.3 | 652.4 | 501.8 |

| 15 | VQWKVDNALQSGNSQESVTEQDSK | IGKC (P01834, K41) | 12.7 | 947.1 | 941.1 |

| 16 | DSTYSLSSTLTLSKADYEK | IGKC (P01834, K75) | 16.4 | 757.7 | 751.7 |

| 17 | VYACEVTHQGLSSPVTKSFNR | IGKC (P01834, K99) | 12.6 | 848.1 | 830.1 |

| 18 | QVKDNENVVNEYSSELEK | FGB (P02675, K163) | 12.8 | 762.7 | 72.1 |

| 19 | SKAIGYLNTGYQR | A2M (P01023, K1003) | 10.5 | 816.9 | 1255.6 |

| 20 | ALLAYAFALAGNQDKR | A2M (P01023, K1162) | 18.5 | 628.7 | 86.1 |

| 21 | KCSTSSLLEACTFR | TF (P02787, K683) | 13.8 | 911.4 | 884.4 |

| 22 | ADSSPVKAGVETTTPSK | IGLC (P01842, K50) | 8.7 | 613.0 | 70.1 |

| 23 | AKVQPYLDDFQK | APOA1 (P02647, K120) | 12.5 | 807.4 | 765.4 |

| 24 | KWQEEMELYR | APOA1 (P02647, K131) | 10.1 | 530.6 | 524.6 |

| 25 | AVGDKLPECEAVCGKPK | HP (P00738, K141) | 9.4 | 674.0 | 656.0 |

| 26 | M KGLIDEVNQDFTNR | FGA (P02671, K71) | 14.9 | 653.3 | 894.4 |

| 27 | SSSYSKQFTSSTSYNR | FGA (P02671, K581) | 8.7 | 664.6 | 658.6 |

The timed multiple reaction monitoring relied on the retention time of each peptide in RP-HPLC and a specific precursor/fragment ion pair (Q1/Q3 mass range)

t R retention time, C, M , and K carbamidomethylated cysteine, methionine sulfoxide, and fructosamine lysine, HSA human serum albumin, IGKC Ig kappa chain c region, FGB fibrinogen beta chain, A2M alpha-2-macroglobulin, TF serotransferrin, IGLC Ig lambda chain C region, APOA1 apolipoprotein A-I precursor, HP haptoglobin, FGA fibrinogen alpha chain

Peptides were loaded on a C18-column (AdvanceBio Peptide Mapping column, pore size 120 Å, length 150, 2.1 mm internal diameter, 2.7 µm particles, Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany) coupled on-line to ESI–MS. Eluents A and B were water and acetonitrile, respectively, containing both formic acid (0.1%, v/v). Elution was achieved by a linear gradients starting 3 min after sample injection from 3 to 10% eluent B within 1 min, to 20% eluent B within 10 min and to 95% eluent B in 7 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min and the column temperature was set to 60 °C. Quantification relied on timed MRM using specific transitions of each targeted peptide and isotope-labelled internal peptide standards synthesized on solid phase in-house. Quantification was performed by integrating individual peaks in extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) using Analyst 1.6 software (AB Sciex) relative to the coeluting isotope-labelled peptides.

Statistics and bioinformatics

The samples from individuals with or without T2DM were evaluated by different statistical tests (Kolmogorow-Smirnow, Mann–Whitney, and t test) and calculation of Spearman rank correlation coefficients using Prism 6 (GraphPad software; La Jolla, USA). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and screening for variable combination relied on the Excel-add-in Multibase 2015 (Numerical Dynamics) and Prism 6 software, respectively.

The 48 diabetic and 48 samples were classified by a decision tree algorithm using HbA1c in combination with each glycated peptide (Additional file 1: Table S6). The same technique was also applied to FPG (Additional file 1: Table S7). The decision tree algorithm was implemented using Scikit-Learn [24]. Accuracies were evaluated using nested tenfold cross validation [25]. To find the best feature set for classification, a support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) method [26] was applied on all glycated peptides and clinical parameters, including HbA1c, FPG, BMI, etc. Feature normalization and missing value imputation were performed using WEKA toolkit [27]. The support vector machine was implemented using Scikit-Learn [24]. Accuracies and area under the curve (AUC) values were evaluated using nested tenfold cross validation [25]. Hierarchical clustering was performed on 48 diabetic samples using the “hclust” function in R software version 3.2.1 [28]. To find the subclasses in diabetic samples, the expectation–maximization algorithm in Scikit-Learn [24] was applied. The clustering stability score [29] and elbow criterion [30] were used to find the optimal number of subclasses.

Results

The timed MRM method optimized for quantification of the targeted 27 glycated peptides (Table 1) obtained by tryptic digestion from plasma provided limits of detection (LODs) and quantification (LOQs) in the low to high nanomolar range (Additional file 1: Table S3). Intra- and interday precisions showed typically coefficients of variation (CVs) below 20% (Additional file 1: Table S3). The quantities of all 27 glycated peptides normalized to the total protein content of each plasma sample were significantly higher in T2DM than in the control group (P < 0.05, Additional file 1: Figure S1). However, the normalized quantities of all glycated peptides showed a notable overlap. Interestingly, diabetic groups subdivided by an HbA1c threshold of 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) showed very similar average glycation degrees for all peptides, indicating that the glycation degree of hemoglobin in erythrocytes showed only a weak correlation with the glycation levels of serum proteins providing a rationale that they may have different diagnostic and prognostic values.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r S) calculated for each glycated peptide amount and the established diagnostic parameters indicated moderate correlations between a few glycation sites and BMI (−0.54 < r S < −0.38, P < 0.001), body fat (−0.49 < r S < −0.36, P < 0.01), and C-peptide levels (−0.45 < r S < −0.37, P < 0.001) (Additional file 1: Table S4). Correlations between peptide glycation levels and HbA1c were weak (0.11 < r S < 0.34, 0.001 < P < 0.3) to moderate (0.37 < r S < 0.46, P < 0.001) and also weak (−0.08 < r S < 0.30, 0.001 < P < 0.65) for FPG (Additional file 1: Table S4). Besides FPG (r S = 0.40, P < 0.001) and free fatty acids (FFA, (r S = 0.57, P < 0.001) HbA1c showed for further diagnostic parameters only weak correlations (−0.35 < r S < 0.35, 0.001 < P < 0.95). However, FPG showed moderate correlations with fasting plasma insulin (FPI, r S = 0.40, P < 0.001), proinsulin (r S = 0.38, P < 0.01), homeostasis model assessment as an index of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, r S = 0.56, P < 0.001), and fasting plasma free fatty acids (FFA) (r S = 0.56, P < 0.001).

A ROC curve analysis for samples from T2DM patients relative to HbA1c (cut-off 6.5% (48 mmol/mol)) and FPG (cut-off 7.0 mmol/L) provided for all glycated peptides maximal sensitivities and specificities of 79 and 88%, respectively, and AUCs larger than 79% for certain cut-off concentrations (Additional file 1: Table S5). In comparison, sensitivities, specificities, and AUCs of HbA1c were 52, 100, and 86%, respectively, as well as 40, 100, and 84% for FPG using the aforementioned cut-offs. A ROC curve analysis determined the best cut-off values maximizing sensitivity and selectivity as 6.0% (42 mmol/mol) for HbA1c (77 and 94%) and 5.69 mmol/L for FPG (75 and 81%).

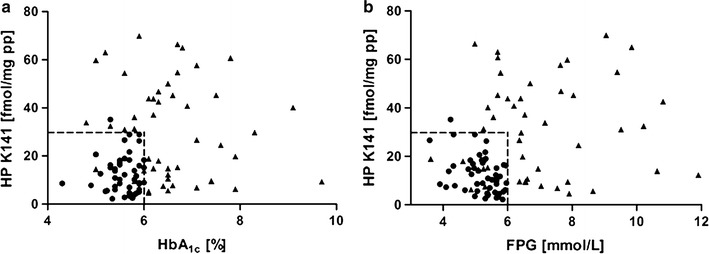

As the diagnostic accuracies of HbA1c (76% for cut-off 6.5% (48 mmol/mol), 86% for cut-off 6.0%), FPG (70% for cut-off 7.00 mmol/L, 78% for cut-off 5.69 mmol/L), and the evaluated glycated peptides (60 to 73%) were insufficient, the data sets were screened by decision tree algorithm for variable combinations of HbA1c or FPG with any glycated peptide for optimal sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy using different cut-off points. HbA1c in combination with glycated peptides yielded mostly sensitivities from 75 to 81%, specificities from 96 to 100%, and accuracies from 87 to 90% (Additional file 1: Table S6). Most interestingly, analyses revealed a haptoglobin peptide glycated at Lys141 (HP K141; sequence No. 25) which provided in combination with HbA1c a sensitivity of 94%, a specificity of 98%, and an accuracy of 96% for cut-off points 6.0% (42 mmol/mol, HbA1c) and 30 fmol/mg (HP K141) (Fig. 1a). When HP K141 was combined with FPG (6.0 mmol/L), sensitivity to detect T2DM was 78%, specificity 98%, and accuracy 88% (Fig. 1b), whereas the other glycated peptides typically provided slightly lower accuracies (Additional file 1: Table S7). Since the decision tree algorithm did not deliver all cut-off values for all combinations, manual confirmation was carried out. Combining manually HbA1c or FPG with glycated peptides provided slightly enhanced diagnostic accuracies for all combinations and could confirm all cut points provided by the algorithm with only small variations (Additional file 1: Tables S8 and S9). Noteworthy, the combination of HP K141 and FPG (6.0 mmol/L) was improved to a sensitivity of 83%, a specificity of 98%, and an accuracy of 91%.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plots of HbA1c values (a) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels (b) against peptide levels corresponding to Lys141 of haptoglobin (HP K141). Numerical values of 48 type 2 diabetes patients (black triangles) and 48 control persons (black circles) are shown. Dashed lines illustrate the cut point chosen for each feature

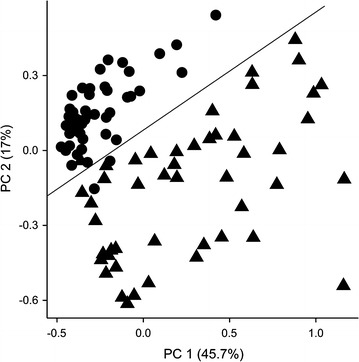

The SVM-RFE method was applied to find a set of diagnostic parameters and peptide amounts for maximizing the classification of T2DM patients and controls. It revealed a set of 15 features providing a sensitivity of 98%, a specificity of 100%, and an accuracy of 99% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Principle component plot shows the clear separation between T2DM patients and controls using the 15 diagnostic parameters: HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), free fatty acids (FAA), triglyceride levels, leukocytes levels, C-reactive protein levels, HOMA-IR, age, waist, waist-to-hip ratio, diastolic blood pressure, and glycated peptides 4, 8, 11, and 25 (Table 1). Values for 48 type 2 diabetes patients (black triangles) and 48 control persons (black circles) are shown. PC1 first principle component, PC2 second principle component

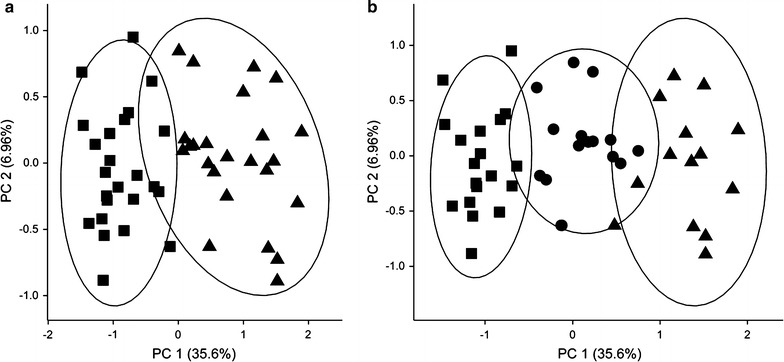

The cluster analysis of the 48 T2DM plasma samples was applied to an expectation–maximation (EM) algorithm considering all glycated peptides and clinical parameters available (27 glycated peptides + 38 clinical parameters). The result showed two or maximal three clusters (Fig. 3). Glycated peptide levels were distinct among different groups, however, clinical parameters, including HbA1c and FPG, were similar. This suggests that glycated peptides can be more useful to detect subtle differences among diabetic patients. A principle component plot is used to visualize the distribution of clusters (Fig. 3). A cluster stability test considering the elbow criterion identified three clusters as optimal number. This was further confirmed by hierarchical clustering that also suggested three groups of T2DM patients (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

Fig. 3.

Principle component plot of the clustering of 48 T2DM patients into two (a) or three (b) clusters based on all available patient information, i.e. diagnostic parameters and glycated peptide levels. Missing values were imputed using Weka. The ellipses are drawn at 95% confidence interval using the level parameter in ggplot. PC1 first principle component, PC2 second principle component

Discussion

Protein glycation as diagnostic criterion has been addressed in many studies for decades [13–17]. Surprisingly, only glycation of intracellular hemoglobin is currently considered as biomarker to monitor patients assuming that HbA1c levels closely reflect average glucose blood levels over the previous 3 months. Plasma proteins have been mostly analyzed for their global glycation degrees [especially human serum albumin (HSA)], which can be attributed to the lack of specific immunoassays, i.e. antibodies recognizing individual glycation sites. As an example, measurement of fructosamine determines the fraction of total serum proteins (mainly serum albumin) that have undergone glycation. Because albumin has a half-life of approximately 3 weeks, the plasma fructosamine concentration reflects relatively recent changes in blood glucose and is therefore not commonly used to monitor diabetes treatment [31].

Additionally, mass spectrometry has been typically applied for mapping glycation sites in serum proteins, whereas quantitative studies on distinct glycation sites in larger patient cohorts are missing. Besides the analytical challenges, this is probably attributed to the general assumption that glycation as a non-enzymatic reaction depends only on the glucose concentration and thus the glycation levels of individual sites will change at similar degrees and thus can be judged from global glycation degrees. Here, we could show that the glycation levels of 27 sites in nine plasma proteins provide significantly different sensitivities, specificities and accuracies for classifying T2DM patients and controls. Most importantly, these glycation degrees correlated only slightly to HbA1c and other clinical parameters like FPG. Additionally, sensitivities of the newly identified glycation sites were mostly better than for HbA1c, while specificities were lower demonstrating that T2DM diagnosis might benefit from combining currently applied clinical parameters with plasma protein glycation sites analyzed in the context of this study. Despite studying 27 glycation sites, it was our aim to identify the diagnostically most relevant modification to keep the number of biomarkers and thus the costs of the envisaged diagnostic tools low. Different statistical analyses identified glycation of Lys141 in haptoglobin as the best parameter in combination with HbA1c and FPG. The obtained sensitivity (94%), specificity (98%), and accuracy (96%) of HP K141 in combination with HbA1c exceeded the corresponding values of HbA1c significantly. This suggests that in addition to HbA1c measurements, glycation of Lys141 in haptoglobin could be used as a diagnostic tool in patients with T2DM and those with a high risk to develop T2DM (Fig. 1a). Further studies are necessary to test whether combination of these two parameters of chronic hyperglycemia may better predict individual risk for the development of diabetes complications. However, an earlier diagnosis of T2DM may be important for individual patients’ outcomes, as it has been demonstrated that a “bad glycemic memory” may contribute to a higher risk of diabetes complications even after periods of well-controlled hyperglycemia [32]. The negative correlation between HP K141 and both BMI and C-peptide appears interesting, as it might indicate higher glycation levels in T2DM patients are caused by both diabetes-specific, but also obesity-associated metabolic alterations, which subsequently may cause chronic hyperglycemia. Negative correlations between glycation levels and BMI suggest that adipose tissue in patients with obesity may have a higher capacity to take up excess glucose before it contributes to glycation of circulating proteins. However, this hypothesis has to be formally proven by glucose distribution studies in lean versus obese animal models under hyperglycemic conditions.

Although our initial intention was to identify a single biomarker, statistical evaluation of the data revealed a promising features selection matrix using three glycation sites in HSA (K93, K262, and K414) besides HP K141 representing short-to-medium term glucose fluctuations in combination with twelve routine parameters typically used to characterize T2DM (FPG, HbA1c, fasting insulin), metabolic syndrome (triglycerides and blood pressure), obesity (BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio), inflammation (leukocytes, C-reactive protein), and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and age [33]. This feature set provided an extremely high accuracy of 99% for the sample cohort providing the best diagnostic value that has been reported to the best of our knowledge. For example, a feature set reported in 2009 relied on 160 individuals (Danish Inter99 prospective study), who progressed from initially non-diabetic to diabetes during the following five years. The predictive values of 58 biomarkers (selected from presumed diabetes-associated pathways) together with six routine clinical parameters were evaluated by statistical learning methods [34]. The best features, i.e. six biomarkers (adiponectin, C-reactive protein, ferritin, interleukin-2 receptor A, glucose, and insulin), were used in a PreDx diabetes risk score (DRS) model providing an AUC of 0.76 that increased to 0.78 when family history, age, BMI, and waist circumference were added. A later report indicated an AUC of 0.838 [35]. The PreDx DRS model outperformed single variables like FPG (~0.73) and HbA1c (~0.66) significantly. In this respect the 15 feature set selected here considering only four new biomarkers besides routine laboratory measures, provides a better diagnostic accuracy with on the AUC of 0.99375 (accuracy 99%).

Another intriguing result of statistical evaluation and hierarchical clustering was the separation of diabetes patients in three subgroups based on all patient information including all 27 glycation sites (Fig. 3; Additional file 1: Figure S2). At this stage, the clinical relevance remains open, but it is compelling to speculate that the subgroups might represent distinct subgroups of T2DM. This hypothesis is supported by a recent report that three T2DM subgroups have been dissected through topological analysis of patient similarity [36]. In this analysis, one T2DM subtype was characterized by diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy, another showed enriched risk for malignancies and cardiovascular diseases, whereas the third subtype correlated most strongly with cardiovascular diseases, neurological diseases, allergies, and specific infections. Based on this data, future longitudinal studies, which assess the risk of these disease entities in addition to the glycation sites described in our study should be performed to test the hypothesis that these three subtypes could be distinguished by protein glycation markers.

These subgroups may also respond differently to multifactorial T2DM treatment strategies or may predict the progression of the disease itself and the individual risk for developing diabetes complications. Noteworthy, our study has some limitations with regard to the small size of our discovery cohort and the limited transferability into clinical practice. Although we only included newly diagnosed T2DM patients at the earliest possible time point and without antidiabetic treatment, we cannot relate the time point of diagnosis to a defined metabolic state. In addition, we could not exclude individual differences in the duration and severity of the prediabetic phase including chronic effects of intermittent glucose and lipid toxicity. Moreover, the suggestion that glycated Lys141 in haptoglobin may improve diagnostic accuracy for T2DM needs to be tested in prospective studies and cohorts representing the common population.

In conclusion, the 27 glycation sites quantified here provided sensitivities up to 79% and specificities of up to 88% to distinguish T2DM samples relative to age- and BMI-matched control samples using specific cut-offs for each glycation site. The cut-off values of HbA1c (6.5% (48 mmol/mol)) and FPG (7.0 mmol/L) recommended by the WHO showed better specificities of 100%, but lower sensitivities of only 52 and 40%, respectively. Interestingly, lowering the cut points to 6.0% (42 mmol/mol) and 5.69 mmol/L improved the sensitivity significantly to 77 and 75%, respectively, while the selectivity was reduced to 94 and 81%, respectively. This is in good agreement with recent reports suggesting that lower HbA1c and FPG cut points will dramatically increase diagnostic sensitivity [37–41]. Remarkably, plasma proteins appeared to follow other glycation kinetics than hemoglobin, which might be related to their different environment (i.e. blood versus erythrocytes). Thus, glycation sites in plasma proteins may provide an additional diagnostic tool, as confirmed here by combining the glycation levels HbA1c and HP K141 providing high sensitivity (94%) and specificity (98%). The advantage of combining these two markers are the different half-life times of the corresponding proteins, i.e. 3–4 months for intracellular hemoglobin and two to four days for haptoglobin (t 1/2 = 2–4) [42] being sensitive to long- and short-term fluctuations of blood glucose concentrations. Furthermore, the combination of 15 features consisting of established clinical parameters and several glycated plasma proteins allowed dividing the newly diagnosed patients with T2DM into three different subgroups supporting the hypothesis that heterogeneity of T2DM phenotypes maybe due differentially affected pathways including significant differences in protein glycation.

Authors’ contributions

SS researched data, contributed to discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. YL and LW researched data, contributed to discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. MB and RH contributed to discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Uta Greifenhagen, Dr. Andrej Frolov, and Dr. Ravi Chand Bollineni for the help with sample preparation and helpful discussions and Dr. Daniel Knappe, Dr. David Singer, and Tina Goldbach for their support in synthesizing the peptides.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of supporting data

The datasets during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universität Leipzig (approval no: 159-12-21052012), and performed in accordance to the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Funding

Financial support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HO-2222/7-1 to RH and SFB 1052: Obesity Mechanisms, B01 to MB) is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- ADA

American Diabetes Association

- AUC

area under the curve

- BAC

boronic acid affinity chromatography

- BMI

body mass index

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CV

coefficient of variation

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- EM

expectation–maximation

- ESI–MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- FFA

free fatty acids

- FPG

fasting plasma glucose

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment as an index of insulin resistance

- HP K141

glycated lysine-141 of haptoglobin

- HSA

human serum albumin

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LOD

limit of detection

- LOQ

limit of quantification

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- RP-HPLC

reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- SPE

solid phase extraction

- SVM-RFE

support vector machine-recursive feature elimination

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- WHO

World Health Organization

- XIC

extracted ion chromatogram

Additional file

Additional file 1. Table S1. Characterization of type 2 diabetes patients and matched non-diabetic persons enrolled in this study. Table S2. Parameters and settings used for the RP-HPLC-ESI-QqLIT-MS operating in scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Table S3. Precision, sensitivity and linearity parameters for glycated peptides. Table S4. Spearman rank correlation coefficients (rS) and corresponding P values (P) of the statistical relation between glycated peptides and several diagnostic parameters. Table S5. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) parameters for peptide levels of all 27 glycated peptides quantified in tryptic digests of plasma samples obtained from 48 type 2 diabetes patients and 48 controls. For comparison, ROC parameters of HbA1C and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) are listed. Table S6. Evaluation metrics for classification of type 2 diabetes patients and controls by combining the levels of 27 glycated peptides in tryptic plasma digests and corresponding HbA1c levels calculated by Decision Tree classifier from Scikit-learn package. Table S7. Evaluation metrics for classification of type 2 diabetes patients and controls by combining the levels of 27 glycated peptides in tryptic plasma digests and corresponding FPG levels. Table S8. Evaluation metrics for classification of type 2 diabetes patients and controls by combining the levels of 27 glycated peptides in tryptic plasma digests and corresponding HbA1c levels. Variable cut points were optimized manually for best classification. Table S9. Evaluation metrics for classification of type 2 diabetes patients and controls by combining the levels of 27 glycated peptides in tryptic plasma digests and corresponding fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels. Variable cut points were optimized manually for best classification. Figure S1. Quantification of glycated peptides in tryptic plasma digests obtained from type 2 diabetes patients and non-diabetic controls using internal calibration. Figure S2. Dendrogram resulting from a hierarchical clustering of 48 type 2 diabetes patient samples considering all available patient information, i.e. diagnostic parameters and glycated peptide levels.

Contributor Information

Sandro Spiller, Email: sandro.spiller@uni-leipzig.de.

Yichao Li, Email: yl079811@ohio.edu.

Matthias Blüher, Email: Matthias.Blueher@medizin.uni-leipzig.de.

Lonnie Welch, Email: welch@ohio.edu.

Ralf Hoffmann, Email: bioanaly@rz.uni-leipzig.de.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association (ADA) Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:67–74. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) and International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Abbreviated report of a WHO consultation. Use of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis if diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Sacks DB. Status of hemoglobin A1c measurement and goals for improvement: from chaos to order for improving diabetes care. Clin Chem. 2011;57:205–214. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.148841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka S, Tanaka S, Iimuro S, Yamashita H, Katayama S, Akanuma Y, Yamada N, Araki A, Ito H, Sone H, Ohashi Y. Predicting macro- and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: the Japan Diabetes Complications Study/the Japanese Elderly Diabetes Intervention Trial risk engine. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1193–1199. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leal J, Hayes AJ, Gray AM, Holman RR, Clarke PM. Temporal validation of the UKPDS outcomes model using 10-year posttrial monitoring data. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1541–1546. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox ME, Edelman D. Tests for screening and diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2009;27:132–138. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.27.4.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao Q, Dekker JM, de Vegt F, Nijpels G, Nissinen A, Stehouwer CD, Bouter LM, Heine RJ, Tuomilehto J. Two prospective studies found that elevated 2-hr glucose predicted male mortality independent of fasting glucose and HbA1c. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:590–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, Sivakumaran R, Nethercott S, Preiss D, Erqou S, Sattar N. Effect of intensive control of glucose on cardiovascular outcomes and death in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1765–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currie CJ, Peters JR, Tynan A, Evans M, Heine RJ, Bracco OL, Zagar T, Poole CD. Survival as a function of HbA(1c) in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:481–489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61969-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McEwen LN, Karter AJ, Waitzfelder BE, Crosson JC, Marrero DG, Mangione CM, Herman WH. Predictors of mortality over 8 years in type 2 diabetic patients: translating research into action for diabetes (TRIAD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1301–1309. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faerch K, Vistisen D, Johansen NB, Jorgensen ME. Cardiovascular risk stratification and management in pre-diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2014;14:493. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyons TJ, Basu A. Biomarkers in diabetes: hemoglobin A1c, vascular and tissue markers. Transl Res. 2012;159:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rondeau P, Bourdon E. The glycation of albumin: structural and functional impacts. Biochimie. 2011;93:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frolov A, Hoffmann R. Identification and relative quantification of specific glycation sites in human serum albumin. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:2349–2356. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Monroe ME, Schepmoes AA, Clauss TRW, Gritsenko MA, Meng D, Petyuk VA, Smith RD, Metz TO. Comprehensive identification of glycated peptides and their glycation motifs in plasma and erythrocytes of control and diabetic subjects. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3076–3088. doi: 10.1021/pr200040j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frolov A, Blüher M, Hoffmann R. Glycation sites of human plasma proteins are affected to different extents by hyperglycemic conditions in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406:5755–5763. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kloting N, Fasshauer M, Dietrich A, Kovacs P, Schon MR, Kern M, Stumvoll M, Bluher M. Insulin-sensitive obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E506–E515. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00586.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannt A, Pfenninger A, Teichert L, Tonjes A, Dietrich A, Schon MR, Kloting N, Bluher M. Association of nicotinamide-N-methyltransferase mRNA expression in human adipose tissue and the plasma concentration of its product, 1-methylnicotinamide, with insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2015;58:799–808. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson L, Hunter CL. Quantitative mass spectrometric multiple reaction monitoring assays for major plasma proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:573–588. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500331-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frolov A, Hoffmann R. Analysis of amadori peptides enriched by boronic acid affinity chromatography. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1126:253–256. doi: 10.1196/annals.1433.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiller S, Frolov A, Hoffmann R. Quantification of specific glycation sites in human serum albumin as prospective type 2 diabetes mellitus biomarkers. Protein Pept Lett. 2017;24. doi:10.2174/0929866524666170202124120. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kuzyk MA, Smith D, Yang J, Cross TJ, Jackson AM, Hardie DB, Anderson NL, Borchers CH. Multiple reaction monitoring-based, multiplexed, absolute quantitation of 45 proteins in human plasma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1860–1877. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800540-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R, Dubourg V. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Xuan J, Wang C, Shih Ie M, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Hoffman E, Clarke R. Knowledge-guided multi-scale independent component analysis for biomarker identification. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:416. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyon I, Weston J, Barnhill S, Vapnik V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach Learn. 2002;46:389–422. doi: 10.1023/A:1012487302797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall M, Frank E, Holmes G, Pfahringer B, Reutemann P, Witten IH. The WEKA data mining software: an update. ACM SIGKDD Explor Newsl. 2009;11:10–18. doi: 10.1145/1656274.1656278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. ISBN: 3-900051-07-0. http://www.R-project.org/.

- 29.von Luxburg U. Clustering stability: an overview. Found Trends Mach Learn. 2009;2:235–274. doi: 10.1561/2200000008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ketchen DJ, Shook CL. The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: an analysis and critique. Strateg Manag J. 1996;17:441–458. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199606)17:6<441::AID-SMJ819>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danese E, Montagnana M, Nouvenne A, Lippi G. Advantages and pitfalls of fructosamine and glycated albumin in the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;9:169–176. doi: 10.1177/1932296814567227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianchi C, Del Prato S. Metabolic memory and individual treatment aims in type 2 diabetes–outcome-lessons learned from large clinical trials. Rev Diabetes Stud. 2011;8:432–440. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2011.8.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meigs JB. Multiple biomarker prediction of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1346–1348. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolberg JA, Jørgensen T, Gerwien RW, Hamren S, McKenna MP, Moler E, Rowe MW, Urdea MS, Xu XM, Hansen T, et al. Development of a type 2 diabetes risk model from a panel of serum biomarkers from the Inter99 cohort. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1207–1212. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urdea M, Kolberg J, Wilber J, Gerwien R, Moler E, Rowe M, Jorgensen P, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Jorgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K. Validation of a multimarker model for assessing risk of type 2 diabetes from a five-year prospective study of 6784 Danish people (Inter99) J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:748–755. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Cheng WY, Glicksberg BS, Gottesman O, Tamler R, Chen R, Bottinger EP, Dudley JT. Identification of type 2 diabetes subgroups through topological analysis of patient similarity. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:311–325. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buell C, Kermah D, Davidson MB. Utility of A1C for diabetes screening in the 1999–2004 NHANES population. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2233–2235. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer CK, Araneta MRG, Barrett-Connor E. A1C and diabetes diagnosis: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:101–103. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carson AP, Reynolds K, Fonseca VA, Muntner P. Comparison of A1C and fasting glucose criteria to diagnose diabetes among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:95–97. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Hanley AJ, Rewers MJ, Karter AJ, Haffner SM. A1C between 5.7 and 6.4% as a marker for identifying pre-diabetes, insulin sensitivity and secretion, and cardiovascular risk factors: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2104–2109. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Pang Z, Gao W, Wang S, Zhang L, Ning F, Qiao Q. Performance of an A1C and fasting capillary blood glucose test for screening newly diagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes defined by an oral glucose tolerance test in Qingdao, China. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:545–550. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carter K, Worwood M. Haptoglobin: a review of the major allele frequencies worldwide and their association with diseases. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007;29:92–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]