Abstract

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the deadliest malignancies worldwide. Radiotherapy plays a critical role in the curative management of inoperable ESCC patients. However, radioresistance restricts the efficacy of radiotherapy for ESCC patients. The molecules involved in radioresistance remain largely unknown, and new approaches to sensitize cells to irradiation are in demand. Technical advances in analysis of mRNA and methylation have enabled the exploration of the etiology of diseases and have the potential to broaden our understanding of the molecular pathways of ESCC radioresistance. In this study, we constructed radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cell lines (TE-1/R and Eca-109/R, respectively). The radioresistant cells showed an increased migration ability but reduced apoptosis and cisplatin sensitivity compared with their parent cells. mRNA and methylation profiling by microarray revealed 1192 preferentially expressed mRNAs and 8841 aberrantly methylated regions between TE-1/R and TE-1 cells. By integrating the mRNA and methylation profiles, we related the decreased expression of transcription factor Sall2 with a corresponding increase in its methylation in TE-1/R cells, indicating its involvement in radioresistance. Upregulation of Sall2 decreased the growth and migration advantage of radioresistant ESCC cells. Taken together, our present findings illustrate the mRNA and DNA methylation changes during the radioresistance of ESCC and the important role of Sall2 in esophageal cancer malignancy.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC); radioresistance; promoter methylation, Sall2

Introduction

Esophageal cancer ranks as the ninth most common malignancy and the sixth most common cause of cancer-related death, with elevated incidence and mortality rates in developing countries 1, 2. The incidence of esophageal cancer in China is particularly high, with approximately one-half of newly diagnosed cases occurring in the world. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) constitutes more than 90% of diagnosed esophageal cancer 1-3. In China, radiotherapy is the primary treatment for this cancer especially when it occurs in the upper or middle thoracic esophagus 3, 4.

Radiotherapy plays a critical role in the curative management of inoperable ESCC patients and after-operational ESCC patients 5, which can significantly prolong patient survival and improve the local control rates of tumors 6. However, tumors treated with fractionated doses of ionizing radiation (IR) often acquire radioresistance 7, which has emerging as an important factor in restricting the efficacy of radiotherapy for ESCC patients. Mechanisms to explain radiation resistance include cancer stem cells (CSCs) 8,9, DNA damage repair systems 10, hypoxia 11, anti-apoptotic capability 12, Wnt/β-catenin 13, mTOR 14 and histone modifications 7. However, reports describing key molecules driving radiation resistance are still limited. Systematic analysis of genome-wide gene expression may extend our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying this process and provide comprehensive information for the development of new strategies to overcome ESCC radioresistance by manipulating key targets. Gene expression profiling by high-throughput technologies has become a valuable tool in mining key molecules and complex gene regulatory circuits 15, 16.

DNA methylation is the most extensively studied epigenetic modification of mammalian DNA. DNA methylation of cytosine residues usually occurs in CpG sequences and has been characterized as an important regulatory mechanism of multiple pathological and physiological processes, including development, inflammation and carcinogenesis. DNA methylation is also implicated in radio- and/or chemotherapies. Identification of methylation alterations involved in acquired radioresistance may provide new insights into its progression 17-19.

The mRNA and methylation profiles of radioresistant ESCC have not been analyzed, and there is currently little information published on the mechanism of acquired radioresistance. Extensive investigation of the molecular etiology, as well as the treatment, of radioresistance is warranted. In this study, we screened radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cell lines and characterized their malignancies. Microarray-based profiling revealed thousands of preferentially expressed mRNAs and aberrantly methylated regions in TE-1/R cells compared with TE-1 cells. By analyzing the mRNA and methylation profiles, we identified a possible correlation between Sall2 demethylation and its upregulated expression in radioresistant cells. We further characterized the role of Sall2 in the radioresistance of ESCC cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, irradiation and construction of radioresistant cell lines

The human esophageal cancer cell lines, TE-1 and Eca-109, were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cells were grown in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2.

Cells were exposed to a single dose of X-ray irradiation using a linear accelerator (RadSource, Suwanee, GA) at a dose rate of 1.15 Gy/min and 160 kV X-ray energy. The method for establishing radioresistant cell line by fractionated irradiation has been described previously 20 with modifications. Briefly, the cell line was first grown to approximately 70% confluence in dishes. Cells were irradiated with 2 Gy of X-ray irradiation. The cells were then returned to the incubator. When they reached approximately 70% confluence, the cells were again irradiated with 2 Gy X-ray irradiation. The fractionated irradiations were continued until the total concentration reached 30 Gy. The radioresistant cell subline was then established. The parent cells were subjected to identical trypsinization, replating, and culture conditions but were not irradiated.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cells were plated in 96-well plates. The next day, the cells were exposed to indicated treatments according to the experimental design. The cells were then incubated with 20 µl MTT (5 mg/ml) for 4 h. After the medium was removed, 100 µl DMSO was added, and the optical density (OD) at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The viability index was calculated as experimental OD value/control OD value. Three independent experiments were performed in quadruplicate.

Clonogenic assay

TE-1/ TE-1/R and Eca-109/ Eca-109/R cells were re-suspended and seeded into six-well plates at 200-6,000 cells/well depending on the dose of radiation 24 h before irradiating with doses of a single fraction of 0, 2, 4, 6 or 8 Gy X-ray irradiation. After incubation for 10-14 days, the cells were subsequently fixed with methanol and stained using 1% crystal violet in 70% ethanol. Colonies containing 50 or more cells were counted. SF (surviving fraction) = number of colonies/(cells inoculated × plating efficiency). The survival curve was derived from a multi-target single-hit model: SF=1-1-exp(-D/D0)n 18.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell apoptosis

Cells were treated with 6 Gy irradiation and harvested 24 h after the treatment. Apoptosis was measured using propidium iodide (PI)/Annexin-V double staining following the manufacturer's instructions (Keygen Biotech, Nanjing, China). Apoptotic fractions were measured using flow cytometry (Beckman, USA). The Annexin-V+/PI- cells are early in the apoptotic process, and Annexin-V+/PI+ indicates late apoptosis. The percentage of both types of cells was counted.

Wound-healing migration assay

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and allowed to form a confluent monolayer for 24 h. After treatment, the monolayer was scratched with the tip of a 200 μL pipette and then washed twice with PBS to remove the floating and detached cells. Then, fresh serum-free medium was added, and photos were taken at 0 and 24 h to assess cell migration using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

mRNA microarray analysis

For mRNA microarray analysis, total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufactures' procotols. Microarray-based mRNA expression profiling was performed using the Roche-NimbleGen (135K array) Array (Roche, WI). The microarrays contained approximately 45,033 assay probes corresponding to all of the annotated human mRNA sequences (NCBI HG18, Build 36). Total RNA labeling and hybridization were performed using standard conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mRNA microarray analysis was carried out at Shanghai Genenergy Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Methylation microarray analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells using the SDS and proteinase K methods and then subjected to sodium bisulfite treatment as reported previously 21,22. The converted DNA was subjected to analysis via the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation 450K BeadChip by Genergy Biotech (Shanghai, China). The methylation levels of CpGs were described as beta values (0 to 1) representing the calculated level of methylation (0% to 100%). We had two technical and two biological replicates processed by chip technique following the manufacturer's standard workflow under the help of Shanghai Genenergy Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

KEGG pathway analysis

KEGG pathway analyses were performed as previously described 23. An adjusted P-value that is lower than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant deviation from the expected distribution, and thus the corresponding KEGG pathways were enriched in target genes. We analyzed all of the differentially expressed mRNAs or genes using KEGG pathway analyses.

DNA extraction and bisulfite sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from esophageal cancer cells using the SDS and proteinase K methods and then subjected to sodium bisulfite treatment 21,22. We amplified and sequenced the first exon of Sall2 gene. This region contains 13 CpG sites. These regions were amplified using the primers (forward) 5'- GTTGGGGGAGAGGTATTAATTG -3'; (reverse) 5'- CCTCCCCTTACCCTAACCT -3'. The initial denaturation was for 2 min at 96°C, followed by 30 cycles for 10 s at 94°C, 5 s at 55°C and 10 s at 72°C and a final elongation for 7 min at 72°C. The amplification of the converted DNA was carried out at OEBiotech (Shanghai, China). The PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, extracted and then cloned into the T-easy vector (Tiangen, China). After bacterial amplification of the cloned PCR fragments by standard procedures, ten clones were subjected to DNA sequencing.

Sall2 overexpression and cell transfection

The Sall2 overexpression vector (pcDNA3.1-Sall2) used in this study were constructed by Bioworld. Ltd. (Nanjing, China). The vector was sequenced for confirmation. For transfection, cells were seeded at 60-70% confluence and transfected by Lipofect (Tiangen, Beijing, China).

Western blot

Cells were lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and subjected to Western blot. Thirty micrograms of protein from each lysate was fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in PBS-Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were blotted with the appropriate Sall2 antobody (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis,MO) or GAPDH primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Membranes were then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies linked to horseradish peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. After TBST washes, the blot was incubated using the ECL detection kit (Beyotime, Nantong, China).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. Standard error bars were included for all data points. The data were then analyzed using Student's t test when only two groups were present or assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when more than two groups were compared. Correlation analysis of the mRNA expression data was performed using the Pearson's test. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (Release 17.0, SPSS Inc.) as used previously 24. Data were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Screening of radioresistant esophageal cancer cells

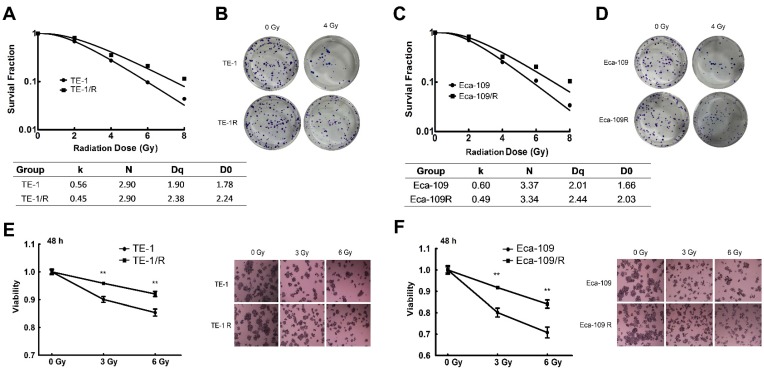

To characterize the underlying mechanism of radioresistance of ESCC cells during radiotherapy, we screened radiation-resistant ESCC TE-1 and Eca-109 cells. Both cell lines were treated repetitively with 2 Gy of X-ray irradiation, with approximately 3-5 days recovery allowed between each fraction until the total concentration reached 30 Gy. The radioresistant cells were named TE-1/R and Eca-109/R, respectively. A clonogenic assay was used to analyze their radiosensitivity after exposure to 0-8 Gy X-ray irradiation. Fig. 1 shows the survival curves of parent and radioresistant cells. Surviving fractions are shown in Fig. 1A and 1C. The TE-1/R subline was more resistant to irradiation than the parent TE-1 cell line (Fig. 1A and 1B). The screened TE-1/R cells were used for the subsequent studies. Similarly, radioresistant Eca-109 (Eca-109/R) cells were screened (Fig. 1C and 1D).

Fig 1.

Clonogenic cell survival curves of the parent and radioresistant esophageal cancer cells. (A) Clonogenic cell survival curves from TE-1 and radioresistant TE-1 (TE-1/R) cells were generated, and D0, Dq and SER values were calculated according to the multi-target single-hit model. (B) Representative clonogenic plates of TE-1 and TE-1/R cells after 0 or 4 Gy irradiation. (C) Clonogenic cell survival curves from Eca-109 and radioresistant Eca-109 (Eca-109/R) cells. (D) Representative clonogenic plates of Eca-109 and Eca-109/R cells after 0 or 4 Gy irradiation. (E) MTT assay of TE-1 cells after 0, 3 and 6 Gy irradiation. (F) MTT assay of Eca-109 cells after 0, 3 and 6 Gy irradiation. Data are normalized to the control cells and presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

The MTT cell viability assay confirmed that the radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cells showed significantly increased cell viability after 0, 3 or 6 Gy irradiation (Fig. 1E-1H). However, there was no obvious morphological difference between radioresistant esophageal cancer cells and their corresponding parent cells (photos not shown).

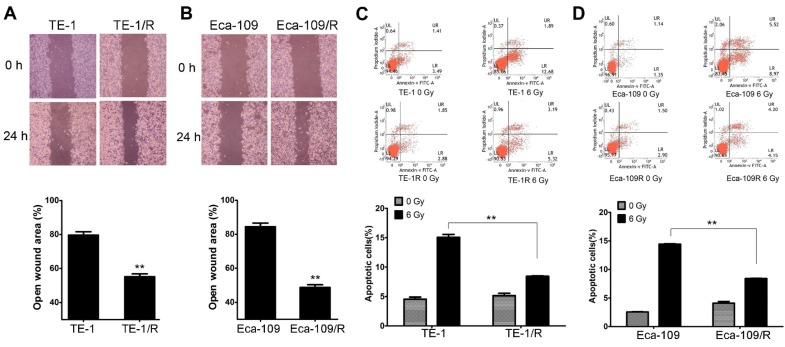

Radioresistant ESCC cells showed increased malignancy

We next investigated the biological changes of the TE-1/R and Eca-109/R cells. Because increased motility is also an important characteristic of metastatic cells 6,8, radioresistant cells were subjected to an in vitro wound-healing assay. Confluent TE-1 and TE-1/R cell cultures were scraped to create a wound, and cell migration was assessed 24 h later. As shown in Fig. 2A, compared with parent TE-1 cells, TE-1/R cells demonstrated a narrower wound area (43.70% of the control group). Similarly, Eca-109/R cells exhibited significantly enhanced migration rates compared to Eca-109 cells (Fig. 2B), suggesting that radioresistant ESCC cells were associated with stronger metastatic potential.

Fig 2.

Radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cells showed more aggressive malignancies. (A) Wound-healing assay of TE-1 and TE-1/R cells. (B) Wound-healing assay of Eca-109 and Eca-109/R cells. Wound healing was observed 24 h after the treatment. (C) Induction of apoptosis by radiation in TE-1 and TE-1/R cells. (D) Induction of apoptosis by radiation in Eca-109 and Eca-109/R cells. Cells were treated with 6 Gy irradiation, and the apoptosis was measured using propidium iodide (PI)/Annexin-V double staining. Data are normalized to the control cells and presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Apoptotic analysis was used to compare apoptosis between parent and radioresistant esophageal cells. The results revealed that TE-1/R and Eca-109/R cells showed significantly (~50%) reduced apoptotic percentages after 6 Gy irradiation compared with parent TE-1 and Eca-109 cells, respectively (Fig. 2C and 2D).

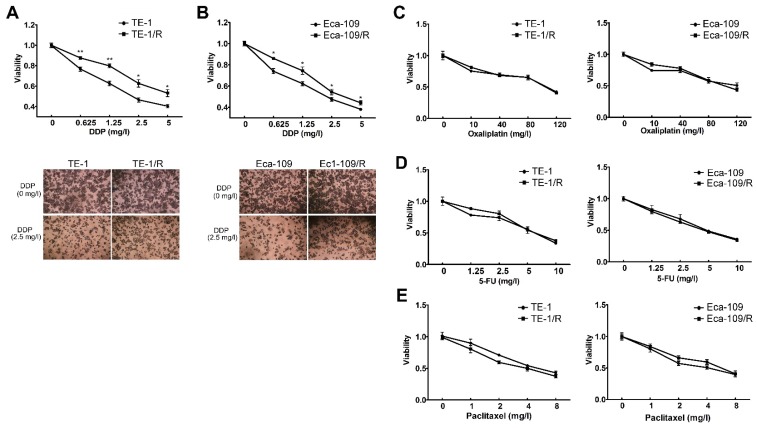

We further explored whether acquired radioresistance affected the chemosensitivity of esophageal cancer cells. TE-1 and TE-1/R cells were treated with cisplatin, oxaliplatin, 5-FU or paclitaxel, and cell viability was determined 48 h later. The results revealed that TE-1/R showed significantly increased resistance to cisplatin (P < 0.01; Fig. 3A) but not oxaliplatin, 5-FU and paclitaxel (Fig. 3C-3E). Similar results were obtained for Eca-109 and Eca-109/R cells (Fig. 3B-3E). The above results indicated that radioresistant esophageal cancer cells exhibited more aggressive malignancies than their parent counterparts.

Fig 3.

Radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cells were resistant to cisplatin. Cells were treated with (A) cisplatin, (B) oxaliplatin, (C) 5-FU and (D) paclitaxel for 48 h. MTT assay of cell viability. The data are shown as the mean ± SEM for three independent experiments. Statistical analysis between the groups was determined by ANOVA; *P < 0.05.

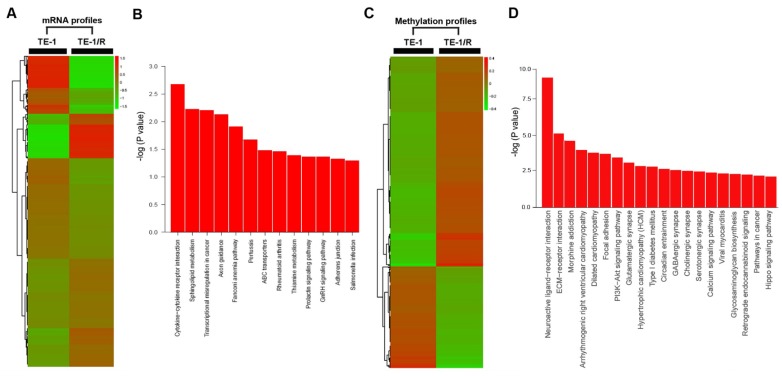

mRNA profiling in radioresistant TE-1 cells

To further analyze the underlying mechanisms responsible for radioresistance, we screened gene expression between TE-1 and radioresistant TE-1 cells (Fig. 4A). A total of 1192 genes (568 upregulated and 624 downregulated genes) were identified with an expression differential of 5-fold or greater between the two conditions (Fig. 4A, Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Compared with the parent TE-1 cells, a variety of genes were shown to be dysregulated in TE-1/R cells by microarray-based profiling. For example, AMDHD1, ZDHHC2 and ADAP2 were substantially increased in radioresistant TE-1 cells, whereas the expression of CTAG2 and TM4SF4 was decreased. As expected, radiation-resistant TE-1 cells appeared to possess complex alternations in the mRNA profile. Pathway analysis revealed that radiation resistance affected multiple pathways, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, sphingolipid metabolism, transcriptional dysregulation in cancer and the Fanconi anemia pathway (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Significant pathways affected in the mRNA and methylation profiling. (A) Heat map of gene expression between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells. (B) Predicted significant pathways for dysregulated genes. (C) Heat map of methylation profiling between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells. (D) Predicted significant pathways for the genes with dysregulated promoter methylation.

Table 1.

Micorarray analysis of gene expression changes between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells (Top 20).

| Gene Name | Fold Change | Regulation | Gene Name | Fold Change | Regulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS.541982 | 34.71152 | Upregulated | CTAG2 | 560.1796 | Downregulated | |

| HS.197018 | 32.33509 | Upregulated | TM4SF4 | 45.22517 | Downregulated | |

| AMDHD1 | 30.86251 | Upregulated | CTAG1A | 43.75822 | Downregulated | |

| ZDHHC2 | 30.52467 | Upregulated | MAGEC1 | 36.33354 | Downregulated | |

| ADAP2 | 29.6555 | Upregulated | SIRPA | 33.46285 | Downregulated | |

| HS.156892 | 29.22589 | Upregulated | UBN1 | 31.92754 | Downregulated | |

| HS.567436 | 28.68791 | Upregulated | MMP23B | 31.55958 | Downregulated | |

| HS.241559 | 27.81247 | Upregulated | HS.577888 | 30.29996 | Downregulated | |

| ZMYM3 | 27.56363 | Upregulated | ELF2 | 29.91821 | Downregulated | |

| MTL5 | 27.53284 | Upregulated | SMARCD3 | 29.77733 | Downregulated | |

| PI4K2B | 27.04118 | Upregulated | XYLT1 | 29.42188 | Downregulated | |

| LOC284757 | 26.82186 | Upregulated | PPP2R2C | 28.46226 | Downregulated | |

| DKK2 | 26.59752 | Upregulated | DOK1 | 28.18455 | Downregulated | |

| HMGA1 | 26.19927 | Upregulated | HS.539444 | 26.5096 | Downregulated | |

| FER1L5 | 25.95929 | Upregulated | RPRML | 26.48736 | Downregulated | |

| EPHA6 | 25.77428 | Upregulated | HS.578356 | 26.02025 | Downregulated | |

| HS.554298 | 24.09793 | Upregulated | HS.560407 | 25.70173 | Downregulated | |

| CD80 | 23.98168 | Upregulated | OR1J1 | 25.41508 | Downregulated | |

| HS.50125 | 23.11935 | Upregulated | SCN7A | 25.36539 | Downregulated | |

| FZD1 | 23.02407 | Upregulated | TIRAP | 24.72349 | Downregulated |

Methylation profiling in radioresistant TE-1 cells

To investigate DNA methylation remodeling as a critical component of acquired radioresistance of esophageal cancer cells, we performed methylation profiling in duplicate using the Infinium Human Methylation 450K BeadChip on parent and radioresistant TE-1 cells. We first sought to identify the differential DNA methylation events present in the radioresistant cell models. We found 5989 CpG sites showing over 20% increased methylation in TE-1/R cells, and 2852 sites showed decreased methylation (>20%) (Fig. 4C, Table 2 and Supplementary 2). Table 2 and Supplementary 2 summarize the methylation frequency of each gene in the TE-1/R cells and their corresponding parent TE-1 cells. The results showed that many genes, such as CSTF2, C6orf10, IGF2AS and VEGFC, had increased methylation in the radioresistant cells. TNR, FAM69C, H19 and ZNF516 showed decreased methylation in the TE-1/R cells compared to the parent cells. Pathway analysis showed that several pathways, such as ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion and the PI3K-Akt signaling pathways, were affected (Fig. 4D).

Table 2.

Micorarray analysis of methylation profiles between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells (Top 20).

| Gene Name | Methylation Difference (%) | Regulation | Gene Name | Methylation Difference (%) | Regulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSTF2 | 0.762786 | Upregulated | TNR | 0.84414 | Downregulated | |

| C6orf10 | 0.733712 | Upregulated | FAM69C | 0.74798 | Downregulated | |

| IGF2AS | 0.674512 | Upregulated | H19 | 0.6772 | Downregulated | |

| VEGFC | 0.667972 | Upregulated | FAM123C | 0.65478 | Downregulated | |

| ZIC3 | 0.66469 | Upregulated | ZNF516 | 0.62958 | Downregulated | |

| DOCK4 | 0.657032 | Upregulated | PIP5K1C | 0.61336 | Downregulated | |

| ZSWIM2 | 0.634047 | Upregulated | NPAS2 | 0.60348 | Downregulated | |

| NMU | 0.631151 | Upregulated | HNRNPA3 | 0.60031 | Downregulated | |

| BTNL2 | 0.621886 | Upregulated | LILRA5 | 0.59961 | Downregulated | |

| TNFSF15 | 0.617575 | Upregulated | GRIK3 | 0.57557 | Downregulated | |

| CDS1 | 0.606077 | Upregulated | ASPSCR1 | 0.5732 | Downregulated | |

| IRS4 | 0.599944 | Upregulated | C18orf62 | 0.55719 | Downregulated | |

| EPHA6 | 0.594247 | Upregulated | ITGB5 | 0.54941 | Downregulated | |

| FAM190A | 0.593273 | Upregulated | GPSM1 | 0.5483 | Downregulated | |

| RGS21 | 0.589113 | Upregulated | RNF145 | 0.54683 | Downregulated | |

| NUBPL | 0.586494 | Upregulated | WNT7A | 0.5458 | Downregulated | |

| ABCA1 | 0.584809 | Upregulated | TSPAN1 | 0.53343 | Downregulated | |

| B3GALT1 | 0.573503 | Upregulated | CAMTA2 | 0.53128 | Downregulated | |

| ZSWIM2 | 0.570219 | Upregulated | NOVA2 | 0.52785 | Downregulated | |

| NEB | 0.569894 | Upregulated | HOXD11 | 0.52289 | Downregulated |

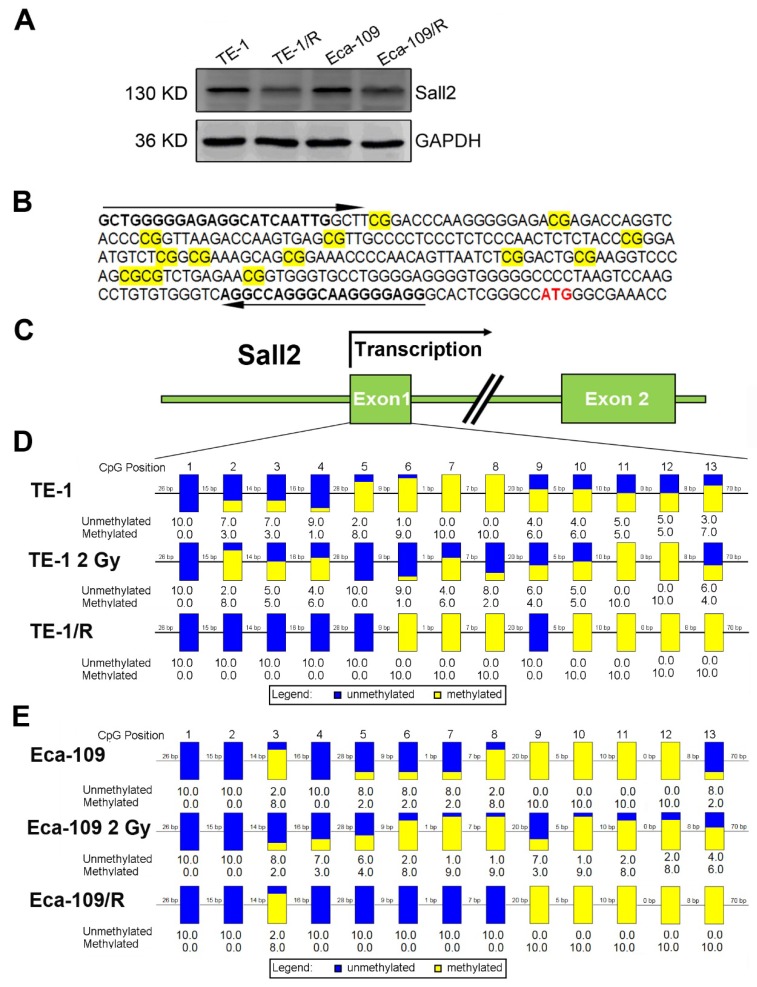

Irradiation induced Sall2 expression by decreasing its promoter methylation

By integrating the mRNA and methylation profiles, we identified decreased expression of transcription factor Sall2 (20.34-fold downregulation) with a corresponding elevated methylation degree in TE-1/R cells, indicating its involvement in the radioresistance by hypomethylation. Therefore, the role of Sall2 in mediating the malignancies was investigated in greater detail. We first confirmed the expression of Sall2 in parent and radioresistant ESCC cell lines by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 5A, TE-1/R and Eca-109/R cells markedly reduced the expression of Sall2 compared with their parent cell lines. We next sought to illustrate the methylation status of the Sall2 promoter by a sodium bisulfite-based sequencing assay. We sequenced 13 potential CpG sites in a predicted CpG island in the first exon of the Sall2 gene in parent, 2 Gy-treated and radioresistant ESCC cells (Fig. 5B and 5C). The results revealed that 2 Gy irradiation induced changes in the methylation degree in the Sall2 promoter. Compared with the parent TE-1 cells, radioresistant TE-1 cells showed demethylation in the No. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 9 CpG sites, while there was increased methylation at the No. 10, 11, 12 and 13 CpG sites (Fig. 5D). In Eca-109 cells, resistant cells exhibited acquired methylation in the No. 13 CpG site (Fig. 5E). These results indicated that radiation modulated the methylation status of the Sall2 promoter and finally reduced its expression.

Fig 5.

Methylation status of Sall2 in parent and radioresistant esophageal cancer cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Sall2 in parent and radioresistant esophageal cancer cells. (B) Sequences for methylation analysis of Sall2 gene. CpG dinucleotides are shaded in yellow. Translational start site for Sall2 is shown in red. The arrows indicate primers used for amplification of the CpG-rich region. (C) Schematic map of Sall2 gene. Exon 1 of Sall2, which contains 13 CpG sites, was predicted as a potential CpG island. After bisulfite treatment of DNA, ten clones of each PCR product were sequenced. (D) The methylation percentage of Sall2 CpG sites in the parent, 2 Gy-treated and radioresistant TE-1 cells. Blue and yellow represent the percentage of methylation for each CpG site. (E) The methylation percentage of Sall2 CpG sites in the parent, 2 Gy-treated and radioresistant Eca-109 cells.

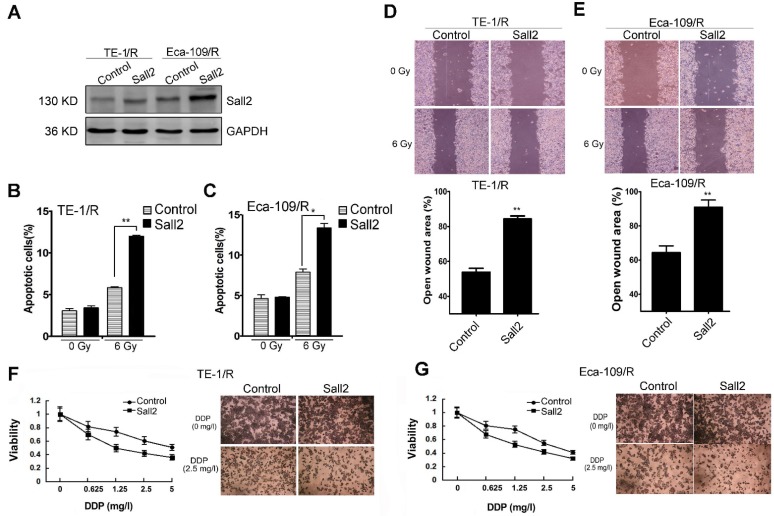

Overexpression of Sall2 decreased the malignancies of radioresistant ESCC cells

Because the expression of Sall2 was reduced in the radioresistant esophageal cancer cells, we sought to investigate whether Sall2 mediated the increased malignancies in radioresistant cells. Cells were first transfected with a control vector pcDNA3.1 (Control) or Sall2-overexpression vector (Sall2), and the resulting cell apoptosis, migration and chemosensitivity were measured. Western blot analysis showed that Sall2 expression was markedly increased following pcDNA3.1-Sall2 transfection (Fig. 6A). The results from cytometry showed that increased Sall2 expression enhanced apoptosis in both TE-1/R and Eca-109/R cells (Fig. 6B and 6C). Cell migration assays showed that forced expression of Sall2 decreased the migration advantages of radioresistant cells (Fig. 6D and 6E). The MTT assay showed that Sall2 decreased the resistance to cisplatin in radioresistant cells (Fig. 6F and 6G). Taken together, these results indicate that overexpression of Sall2 decreased the aggressive malignancies of radioresistant ESCC cells.

Fig 6.

The effect of Sall2 overexpression on the apoptosis, migration and cisplatin sensitivity of esophageal cancer cells. (A) Cells were transiently transfected with control vector or Sall2-overexpression vector (pcDNA3.1-Sall2). The expression of Sall2 was validated by Western blot. Apoptosis of (B) TE-1/R and (C) Eca-109/R cells was measured using propidium iodide (PI)/Annexin-V double staining. (D) Wound-healing assay of cells after the indicated transfection in TE-1/R cells. (E) Wound-healing assay of Eca-109/R cells after the indicated transfection. Wound-healing was observed 24 h after the treatment. (F) TE-1 and (G) Eca-109 cells were treated with cisplatin for 24 h. MTT assay of cell viability. The data are shown as the mean ± SEM for three independent experiments. Statistical analysis between the groups was determined by ANOVA; *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Discussion

Radiotherapy is the standard nonsurgical therapy for esophageal cancer patients 25, 26. Acquired radioresistance during radiotherapy for ESCC patients is a serious concern 4, and its regulating molecular networks remains elusive. Thus, mining gene expression during radioresistance may not only provide insights into the key biological molecules governing radioresistance but also facilitate the understanding of the underlying complex gene regulatory circuits. This is the first report to describe the changes in mRNA profile in ESCC radioresistance, providing insight into the molecular alterations during this process. For example, HMGA1, an architectural transcription factor, is usually overexpressed in cancers. HMGA1 has been shown to promote the resistance to genotoxic agents and anti-cancer drugs, such as gemcitabine 27, 28. Because HMGA1 activates Akt and DNA repair pathways 29, 30, which are both important determinants of radioresistance, it is likely that radiation-induced HMGA1 mediated radioresistance of ESCC cells. Tumor suppressor DOK1 is repressed in multiple types of human tumors as a result of hypermethylation of its promoter region 31. Cancer cells with degradation of DOK1 by BRK acquire more aggressive phenotypes. 32. TM4SF4, a member of the tetraspanin L6 domain family, has been reported to be overexpressed in radiation-resistant lung cancer cells 33. In our study, we found a marked decrease in its expression, suggesting a difference in the mRNA network in radioresistance of different cancers.

DNA methylation mechanisms provide an "extra" layer of transcriptional control that regulates gene expression 34. Epigenetics has recently emerged as one of the most exciting frontiers in the study of radioresistance of cancer cells. The MCF-7 breast cancer cell line showed differential methylation of the CpG regions, including FOXC1 and TRAPPC9 promoters, after fractioned ionization 35. miR-24 was negatively regulated by hypermethylation of its precursor promoter in nasopharyngeal carcinoma radioresistance 36. Hypermethylation of TOPO2A is involved in the radioresistance of human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma 37. The methylation status of ERCC1 is associated with radiosensitivity in glioma cell lines 38. A comprehensive analysis of the methylation and corresponding mRNA profiles during radioresistance of ESCC has not yet been reported. Therefore, using methylation microarray analysis for the parent and radioresistant ESCC cells, we found thousands of genes with altered methylation status. Some of these aberrantly methylated promoters have been identified in previous studies. Notably, multiple CpG sites of noncoding RNA H19 (lncRNA-H19) were demethylated in radiation-resistant cells, indicating activation of its expression. Upregulation of H19 promotes invasion, induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and contributes to occurrence of esophageal cancer 39, 40. The mRNA and methylation changes may contribute to the more aggressive phenotype of radioresistant ESCC cells. However, only a small subset dysregulated mRNAs showed consistent methylation change and pathway analysis also showed few consensus pathways between mRNA and methylation profiling, indicating gene expression during ESCC radioresistance is also regulated by other factors.

After comprehensive interrogation of the transcriptome and the methylome, we correlated repressed expression of Sall2 with increased methylation degree in radioresistant ESCC cells (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Sall2 (Sal-like protein 2), a homeotic transcription factor, is commonly considered as a tumor suppressor 41, 42. Cells with deletion of Sall2 (Sall2-/- MEFs) showed reduced apoptosis with increased cell viability in response to genotoxic stress 43. Consistent with this report, in our study, we found decreased Sall2 expression in radioresistant cells with reduced cell death in response to radiation and cisplatin. The promoter of Sall2 is methylated in ovarian cancer tissues 44. Moreover, restoration of Sall2 expression in cells derived from a human ovarian carcinoma suppresses growth of the cells in immunodeficient mice. Sall2 (p150Sal2) and p53 appear to function similarly in inhibiting cell replication and in inducing apoptosis 45. Sall2 regulates p21 and BAX and functions in some cell types as a regulator of cell growth and survival. Sall2 also regulates P16 in the cell cycle progression 46. Although Sall2 was considered a tumor repressor, its role in radiation resistance has not been characterized. To further investigate the induced function of Sall2, we overexpressed Sall2 and found reversed malignancy of these cancer cells, indicating that Sall2 plays a role in radioresistance. A recent study shows that Sall2 positively regulates Noxa and involves in the apoptotic response to extended genotoxic stress in cancer cells 43. As a transcriptional factor, Sall2 is likely to activate or repress its target genes. Besides P16, Noxa, P21 and BAX, the downstream targets of Sall2 remain poorly elucidated. Further studies are warranted to explore the binding motif under different contexts.

Conclusion

In summary, we constructed radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cells and found that these cells possessed increased migration ability but reduced sensitivity to radiation and cisplatin compared with their parent cells. mRNA and methylation profiling by microarray found 1192 preferentially expressed transcripts and 8841 aberrantly methylated regions between TE-1/R and TE-1 cells. By integrating the mRNA and methylation profiles, we related the decreased expression of transcription factor Sall2 to a corresponding increase in methylation in TE-1/R cells. Upregulation of Sall2 decreased the growth and migration advantage of radioresistant ESCC cells. Our present findings illustrate the mRNA and epigenetic changes during the radioresistance of ESCC and the important role of Sall2 in ESCC malignancy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Micorarray analysis of gene expression changes between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells.

Supplementary Table 2. Micorarray analysis of methylation profiles between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2015HZ004; ZR2016HM41), National Precision Medicine Project of China (2016YFC0904700), Shandong Postdoctoral Innovation Fund (201601006), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BE2015631, BK20151174), Scientific Research of Changzhou (CE20155046).

Authors' contributions

L.G.X. and J.M.Y. conceived and designed the study. J.D.L., W.J.W. and Y.T.T. carried out the molecular biology studies. J.D.L., S.Y.Z. and Q.Z drafted the manuscript and the figures. X.F.Z. and H.Z. performed the statistical analysis. L.G.X. and S.Y.Z. modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- TE-1/R and Eca-109/R

radioresistant TE-1 and Eca-109 cell lines

- IR

ionizing radiation

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- SF

surviving fraction

- PI

propidium iodide

- lncRNA

long noncoding RNA.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, He J. Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2011. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27:2–12. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2015.01.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang WZ, Chen JZ, Li DR, Chen ZJ, Guo H, Zhuang TT. et al. Simultaneous modulated accelerated radiation therapy for esophageal cancer: A feasibility study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13973. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Wu Z, Chen J, Lin X, Zheng C, Fan Y. et al. Postoperative adjuvant therapy for resectable thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 426 cases. Med Oncol. 2015;32:417. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delaney G, Jacob S, Featherstone C, Barton M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilisation from a review of evidence-based guidelines. Cancer. 2006;104:1129–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong Q, Sharma S, Liu H, Chen L, Gu B, Sun X. et al. HDAC inhibitors reverse acquired radio resistance of KYSE-150R esophageal carcinoma cells by modulating Bmi-1 expression. Toxicol lett. 2014;224:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firat E, Gaedicke S, Tsurumi C, Esser N, Weyerbrock A, Niedermann G. Delayed cell death associated with mitotic catastrophe in g-irradiated stem-like glioma cells. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB. et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynam-Lennon N, Reynolds JV, Pidgeon GP, Lysaght J, Marignol L, Maher SG. Alterations in DNA repair efficiency are involved in the radioresistance of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Radiat Res. 2010;174:703–11. doi: 10.1667/RR2295.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan L, Qin Q, Lu J, Liu J, Zhu H, Yang X, Novel poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, AZD2281, enhances radiosensitivity of both normoxic and hypoxic esophageal squamous cancer cells. Dis Esophagus; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin Q, Cheng H, Lu J, Zhan L, Zheng J, Cai J. et al. Small-molecule survivin inhibitor YM155 enhances radiosensitization in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by the abrogation of G2 checkpoint and suppression of homologous recombination repair. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:62. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0062-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H, Luo H, Hu Z, Peng J, Jiang Z, Song T. et al. Targeting WISP1 to sensitize esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to irradiation. Oncotarget. 2015;6:6218–34. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei F, Liu Y, Guo Y, Xiang A, Wang G, Xue X. et al. miR-99b-targeted mTOR induction contributes to irradiation resistance in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:81. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalia M. Biomarkers for personalized oncology: recent advances and future challenges. Metabolism. 2015;64:S16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang Y, Wang YC, Huang QJ. Microarray and next-generation sequencing to analyse gastric cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8033–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahrens TD, Werner M, Lassmann S. Epigenetics in esophageal cancers. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;356:643–55. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1876-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corvalan AH, Maturana MJ. Recent patents of DNA methylation biomarkers in gastrointestinal oncology. Recent Pat DNA Gene Seq. 2010;4:202–9. doi: 10.2174/187221510794751695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takai N, Narahara H. Array-based approaches for the identification of epigenetic silenced tumor suppressor genes. Curr Genomics. 2008;9:22–4. doi: 10.2174/138920208783884892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie L, Song X, Yu J, Wei L, Song B, Wang X. et al. Fractionated irradiation induced radioresistant esophageal cancer EC109 cells seem to be more sensitive to chemotherapeutic drugs. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang S, Lu J, Zhao X, Wu W, Wang H, Wu Q. et al. A variant in the CHEK2 promoter at a methylation site relieves transcriptional repression and confers reduced risk of lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1251–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Zhang S, Xie L, Liu P, Xie F, Wu J. et al. Overexpression of DNA polymerase iota (Polι) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1574–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu C, Chen Y, Zhang H, Chen Y, Shen X, Shi C. et al. Integrated microRNA-mRNA analyses reveal OPLL specific microRNA regulatory network using high-throughput sequencing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21580. doi: 10.1038/srep21580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Li N, Ma ZZ, Tu PF. Comparison of the chemical constituents of aged pu-erh tea, ripened pu-erh tea, and other teas using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:8754–60. doi: 10.1021/jf2015733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minsky BD, Pajak TF, Ginsberg RJ, Pisansky TM, Martenson J, Komaki R. et al. INT 0123 (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 94-05) phase III trial of combined-modality therapy for esophageal cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1167–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith TJ, Ryan LM, Douglass HO, Haller DG, Dayal Y, Kirkwood J. et al. Combined chemoradiotherapy vs. radiotherapy alone for early stage squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:269–76. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniela D, Mussnich P, Rosa R, Bianco R, Tortora G, Fusco A. High mobility group A1 protein expression reduces the sensitivity of colon and thyroid cancer cells to antineoplastic drugs. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:851. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liau SS, Whang E. HMGA1 is a molecular determinant of chemoresistance to gemcitabine in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1470–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liau S, Jazag A, Ito K, Whang E. Overexpression of HMGA1 promotes anoikis resistance and constitutive Akt activation in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:993–1000. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Palmieri D, Valentino T, D'angelo D, De Martino I, Postiglione I, Pacelli R. et al. HMGA proteins promote ATM expression and enhance cancer cell resistance to genotoxic agents. Oncogene. 2011;30:3024–35. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siouda M, Yue J, Shukla R, Guillermier S, Herceg Z, Creveaux M. et al. Transcriptional regulation of the human tumor suppressor DOK1 by E2F1. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:4877–90. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01050-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miah S, Goel RK, Dai C, Kalra N, Beaton-Brown E, Bagu ET, Bonham K, Lukong KE. BRK targets Dok1 for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation to promote cell proliferation and migration. PloS One. 2014;9:e87684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi SI, Kim SY, Lee J, Cho EW, Kim IG. TM4SF4 overexpression in radiation-resistant lung carcinoma cells activates IGF1R via elevation of IGF1. Oncotarget. 2014;5:9823. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Šerman A, Vlahović M, Šerman L, Bulić-Jakuš F. DNA methylation as a regulatory mechanism for gene expression in mammals. Coll Antropol. 2006;30:665–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhmann C, Weichenhan D, Rehli M, Plass C, Schmezer P, Popanda O. DNA methylation changes in cells regrowing after fractioned ionizing radiation. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, Zhang R, Claret FX, Yang H. Involvement of microRNA-24 and DNA Methylation in Resistance of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma to Ionizing Radiation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:3163–74. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JS, Kim SY, Lee M, Kim SH, Kim SM, Kim EJ. Radioresistance in a human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma cell line is associated with DNA methylation changes and topoisomerase II α. Cancer Bio Ther. 2015;16:558–66. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1017154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu ZG, Chen HY, Cheng JJ, Chen ZP, Li XN, Xia Yf. Relationship between methylation status of ERCC1 promoter and radiosensitivity in glioma cell lines. Cell Bio Int. 2009;33:1111–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang C, Cao L, Qiu L, Dai X, Ma L, Zhou Y. et al. Upregulation of H19 promotes invasion and induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in esophageal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:291–6. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao T, He B, Pan Y, Xu Y, Li R, Deng Q. Long non coding RNA 91H contributes to the occurrence and progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting IGF2 expression. Molecular carcinog. 2015;54:359–67. doi: 10.1002/mc.22106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sung CK, Yim H. The tumor suppressor protein p150Sal2 in carcinogenesis. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:489–94. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-3019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung CK, Li D, Andrews E, Drapkin R, Benjamin T. Promoter methylation of the SALL2 tumor suppressor gene in ovarian cancers. Mol Oncol. 2013;7:419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Escobar D, Hepp M, Farkas C, Campos T, Sodir N, Morales M. et al. Sall2 is required for proapoptotic Noxa expression and genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis by doxorubicin. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1816. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sung CK, Li D, Andrews E, Drapkin R, Benjamin T. Promoter methylation of the SALL2 tumor suppressor gene in ovarian cancers. Mol Oncol. 2013;7:419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li D, Tian Y, Ma Y, Benjamin T. p150Sal2 is a p53-independent regulator of p21WAF1/CIP. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3885–93. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3885-3893.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Z, Cheng K, Shi L, Li Z, Negi H, Gao G. et al. Sal-like protein 2 upregulates p16 expression through a proximal promoter element. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:253–61. doi: 10.1111/cas.12606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Micorarray analysis of gene expression changes between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells.

Supplementary Table 2. Micorarray analysis of methylation profiles between TE-1 and TE-1/R cells.