Abstract

BACKGROUND

Data are inconsistent on the association between body mass index (BMI) at time of cancer diagnosis and prognosis. We used data from 22 clinical treatment trials to examine the association between BMI and survival across multiple cancer types and stages.

METHODS

Trials with ≥5 years of follow-up were selected. Patients with BMI<18.5kg/m2 were excluded. Within a disease, analyses were limited to patients on similar treatment regimens. Variable cutpoint analysis identified a BMI cutpoint that maximized differences in survival. Multivariable Cox regression analyses compared survival between patients with BMI above versus below the cutpoint, adjusting for age, race, sex, and important disease-specific clinical prognostic factors.

RESULTS

A total of 11,724 patients from 22 trials were identified. Fourteen analyses were performed by disease site and treatment regimen. A cutpoint of BMI=25kg/m2 maximized survival differences. No statistically significant trend across all 14 analyses was observed (mean HR=0.96, P=.06). In no cancer/treatment combination was elevated BMI associated with an increased risk of death; for some cancers there was a survival advantage for higher BMI. In sex-stratified analyses, BMI≥25kg/m2 was associated with better overall survival among men (HR=0.82; P=.003), but not women (HR=1.04; P=.86). The association persisted when sex-specific cancers were excluded, when treatment regimens were restricted to dose based on body-surface area, and when early stage cancers were excluded.

CONCLUSION

The association between BMI and survival is not consistent across cancer types and stages.

IMPACT

Our findings suggest that disease, stage, and gender specific body size recommendations for cancer survivors may be warranted.

Keywords: Cancer, BMI, survival, overweight, obesity

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, an estimated 69% of the US adult population was overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) and 35% of the population was obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) (1). Overweight and obesity is not only a risk factor for multiple cancers, but is now potentially a prognostic factor associated with cancer survival. Given the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in the US, and the potential for BMI to be an important factor associated with survival outcomes, we need a much better understanding of cancer patient populations at risk for poor BMI-related outcomes. Once this is known, it will be possible to develop and test interventions to improve cancer prognosis among specific high-risk populations.

Higher BMI at the time of a cancer diagnosis has been associated with poorer survival for specific cancer types, including breast cancer (2–5) prostate cancer (6–8), leukemia (9), and oral cancer (10). However, the data are inconsistent for breast cancer (11) and pancreatic cancer (12, 13), and no associations have been observed in ovarian cancer (14), colorectal cancer (15), lymphoma (14), pancreatic cancer, or esophageal cancer (16). In contrast, higher BMI at diagnosis has been associated with better prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia (17), multiple myeloma (18), head and neck cancers (19), and among women with non-Hodgkins lymphoma (9). There are scant data on the effects of BMI at diagnosis among other populations of cancer patients, and few analyses have made comparisons across multiple cancer types or across different stages of cancer diagnosis.

We analyzed the association between baseline BMI and cancer survival using data from 22 clinical trials of common cancer treatments conducted across 14 cancer types and stages within SWOG, formerly known as the Southwest Oncology Group, a member of the National Cancer Institute’s National Clinical Trials Network (1UG1CA189974-01).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Selection of Cohorts and Data Collection

Previously published SWOG phase II and III clinical trials with ≥5 years of follow-up, BMI at trial enrollment and survival data were selected for inclusion. Baseline and survival data were collected according to study-specific case-report forms. All trials included in this analysis were approved by local Human Investigations Committees and all patients provided written informed consent.

Analytic Approach

Overall survival was analyzed by BMI for 14 common treatments across multiple cancers. Underweight patients (BMI<18.5 kg/m2) were excluded given they comprised a small proportion (2%) of total patients and may have had a qualitatively different health status. Trials of similar histology and stage were combined to increase power to detect potential outcome differences by BMI. Within a disease, analyses were limited to patients on similar treatment regimens. For a given treatment regimen, study arms of similar histology and stage were combined to increase power. The 14 cancer/treatment combinations defining the datasets are shown in Supplemental Table 1, including trials of early stage (n=4) and advanced (n=18) disease.

Identification of BMI Cutpoint

To identify a BMI cutpoint that would best differentiate between groups, we examined the predictive value of BMI for overall survival as a binary indicator variable across a range (22 to 35 kg/m2) of potential BMI cutpoint values. BMI cutpoints which defined a subgroup with <10% of overall patients were excluded due to power considerations. For each treatment analysis, the chi-square statistic associated with the effect of the BMI indicator variable on survival in a multivariable regression model was generated. Survival times across the 14 analyses were iteratively truncated in one-year increments from year 1 of follow-up to year 10 of follow-up, to allow a fair comparison across the diverse set of cancer types with different durations of survival. The BMI cutpoint was identified as that level which maximized the average chi-square associated with the effect of BMI on outcome, and was used as the base case for the subsequent survival analyses.

Statistical Analysis of Survival

Using the identified BMI cutpoint, overall survival was analyzed by BMI status above and below the cutpoint within each cancer/treatment cohort. Overall survival was defined as the time between study registration and date of last contact (censored) or death due to any cause. Estimates of overall survival were derived using Kaplan-Meier estimates (20). Multivariable analyses using Cox regression were performed (21). The base case analyses were based on overall survival truncated at five years, which across a diverse set of cancers and prognoses, likely represents the window of follow-up during which treatment has its greatest impact on outcomes. We evaluated whether patients with a higher BMI experienced a different overall survival, and whether patterns of overall survival by BMI status differed by patient sex.

An omnibus test (i.e., p-value) of the global trend across studies was based on a one-sample t-test of the study-specific (signed) Chi-square values representing the statistical significance for the BMI indicator variable in multivariable regression models. Secondary analyses included examination of the BMI cutpoint of 30 kg/m2. In order to establish whether there was a durable association between baseline BMI and survival, conditional survival analysis examined survival patterns in the subset of patients who survived at least one year.

Adjustment Variables in the Regression Models

Regression models incorporated major clinical prognostic factors for each disease, plus demographic factors age (continuous), race (black vs. other; white vs. other) and sex (where appropriate). Each analysis was stratified by study-specific treatment arm to account for possible temporal differences, potential differences in administration/dose, and differences in patient populations not captured by the other prognostic factors. Two-sided p-values are reported.

RESULTS

Cancer/treatment cohorts

Analyses of the association of BMI and outcome were conducted for 14 different treatments based on 11,724 patients from 22 unique trials. Dataset sizes ranged from 241 ovarian cancer patients receiving paclitaxel to 3,145 breast cancer patients receiving doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel. Supplemental Table 1 provides disease, study, and regression covariate descriptions for each cancer/treatment cohort. Details on the eligibility criteria for each of the trials have been previously published (22).

Distribution of BMI Scores

Table 1 shows the distribution of BMI scores within analyses and averaged over all analyses. Based on raw totals, 68% of women and 67% of men were overweight or obese. Using percentages based on study-specific rates, 58% of women and 63% of men were overweight or obese.

Table 1.

Body Mass Index (BMI) Distributions by Cancer Type/Treatment and Sex in 22 SWOG trials (n=11,702)

| Females | Males | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Type Common Treatment |

Normal (18.5–25 kg/m2) n % |

Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) n % |

Obese (≥30 kg/m2) n % |

Normal (18.5–25 kg/m2) n % |

Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) n % |

Obese (≥30 kg/m2) n % |

|

AML Ara-C/DNR |

250 43% |

159 28% |

166 29% |

263 38% |

273 40% |

148 22% |

|

Bladder BCG |

65 58% |

26 23% |

22 19% |

197 33% |

276 47% |

119 20% |

|

Breast CAF × 6 |

489 31% |

526 33% |

579 36% |

NA | NA | NA |

|

Breast CMF × 6 |

157 32% |

165 34% |

162 33% |

NA | NA | NA |

|

Breast AC+Paclitaxel |

788 25% |

949 30% |

1386 44% |

NA | NA | NA |

|

Colorectal 5-FU |

122 43% |

88 31% |

76 27% |

161 42% |

143 37% |

83 21% |

|

NHL CHOP |

67 42% |

38 24% |

56 35% |

95 39% |

98 40% |

49 20% |

|

NSCLC Carboplatin/Paclitaxel |

56 47% |

37 31% |

26 22% |

95 37% |

108 42% |

52 20% |

|

NSCLC Cisplatin+Vinorelbine |

67 55% |

32 26% |

22 18% |

128 50% |

86 34% |

41 16% |

|

Ovarian Paclitaxel |

100 41% |

75 31% |

66 27% |

NA | NA | NA |

|

Prostate Docetaxel |

NA | NA | NA | 73 21% |

137 39% |

138 40% |

|

Prostate Combined ADT |

NA | NA | NA | 309 25% |

548 44% |

394 31% |

|

Renal α-IFN |

37 45% |

21 26% |

24 29% |

81 45% |

69 38% |

31 17% |

|

SARCOMA Imatinib |

126 46% |

75 28% |

70 26% |

136 40% |

126 37% |

75 22% |

| TOTAL N | 2324 | 2191 | 2655 | 1538 | 1864 | 1130 |

|

Percentage based on counts |

32% | 31% | 37% | 34% | 41% | 25% |

|

Percentage based on study-specific rates* |

42% | 29% | 29% | 37% | 40% | 23% |

Abbreviations: 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; a-IFN, interferon alpha; AC, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ara-C, cytarabine; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BMI, body mass index; CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin, and prednisone; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; DNR, daunorubicin; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; P=Paclitaxel

Calculated by giving each study-specific rate equal weight, not weighted according to the size of the study sample

Identification of BMI Cutpoint

Figure 1 shows the chi-square statistic for each BMI cutpoint from 22 kg/m2 to 35 kg/m2. Results indicate that a BMI of 25 kg/m2 maximized the association of BMI and overall survival. The remainder of the primary analysis utilizes a BMI cutpoint of 25 kg/m2 as the base case.

Figure 1. Mean Chi Square by Body Mass Index Cutpoint Level.

Results for different amounts of allowed

followup (1 to 10 years)

Results for different amounts of allowed

followup (1 to 10 years)

The average of all results, by cutpoint

The average of all results, by cutpoint

Each observation in the plot represents the average chi-square statistic for the association of BMI status and overall survival for a given BMI cutpoint, averaged across the 14 different treatment analyses. The dashed lines indicate results for different amounts of allowed followup (1 to 10 years). The solid heavy line shows the average of all results by cutpoint, and indicates that a BMI level of 25 kg/m2, which distinguishes normal weight patients from overweight patients, maximizes the association of BMI and overall survival.

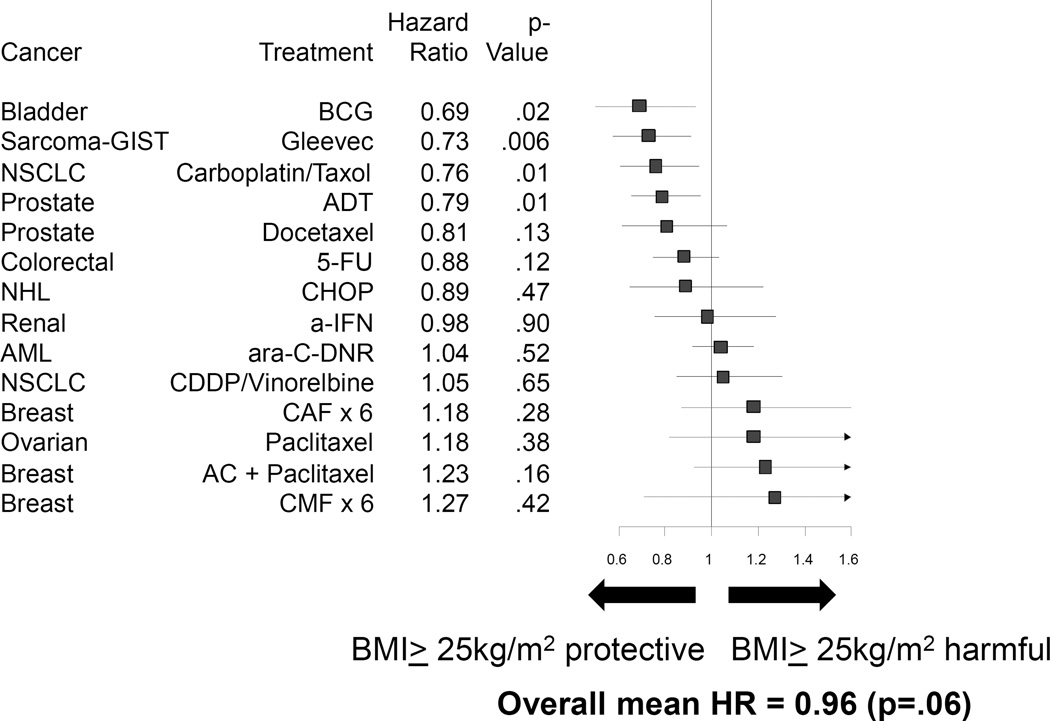

Overall Survival by BMI Status

Figure 2 shows Kaplan Meier curves for each of the 14 analyses with survival truncated at 5 years, using a BMI cutpoint of 25 kg/m2. The hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values for overall survival by disease/treatment combination are shown in the forest plot in Figure 3, in ascending order of the hazard ratio. Patients with elevated BMI had a lower risk of death for those treated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin for bladder cancer (p=.02), treated with imatinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (p=.006), treated with carboplatin+paclitaxel for non-small cell lung cancer (p=.01), and treated with androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer (p=.01). In no cancer/treatment combination was elevated BMI associated with a statistically significantly higher risk of death. The simple (unweighted) overall mean hazard ratio across all cohorts was 0.96 (p=.06), indicating a non-significant trend of a lower risk of death among patients with elevated BMI in this set of 14 groups of trials. While not statistically significant, the hazard ratio for the analyses of breast and ovarian cancer consistently show a detrimental association of elevated BMI with survival. A sensitivity analysis using 3 levels for BMI (BMI<25 vs. BMI 25–30 vs. BMI>30) as an ordinal categorical variable generated similar results in terms of the magnitude and direction of the association of BMI and overall survival (data not shown).

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier Survival Curves, by Cancer and Treatment.

Dashed line = BMI≥25 kg/m2

Solid line = BMI<25 kg/m2

Kaplan Meier survival curves of 14 separate cancer and treatment combinations using data from 22 different SWOG clinical trials.

Abbreviations: 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; a-IFN, interferon alpha; AC, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ara-C, cytarabine; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BMI, body mass index; CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin, and prednisone; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; DNR, daunorubicin; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; P, paclitaxel

Figure 3. Association of BMI and Overall Survival, Based on BMI=25 kg/m2 Cutpoint.

A forest plot displaying hazard ratio (HR) estimates across 14 different cancer and treatment combinations. HR <1 indicates that BMI ≥25 kg/m2 is associated with decreased risk of death, while HR >1 indicates that BMI ≤25 kg/m2 is associated with increased risk of death.

Abbreviations: 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; a-IFN, interferon alpha; AC, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ara-C, cytarabine; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BMI, body mass index; CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin, and prednisone; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; DNR, daunorubicin; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; P, paclitaxel

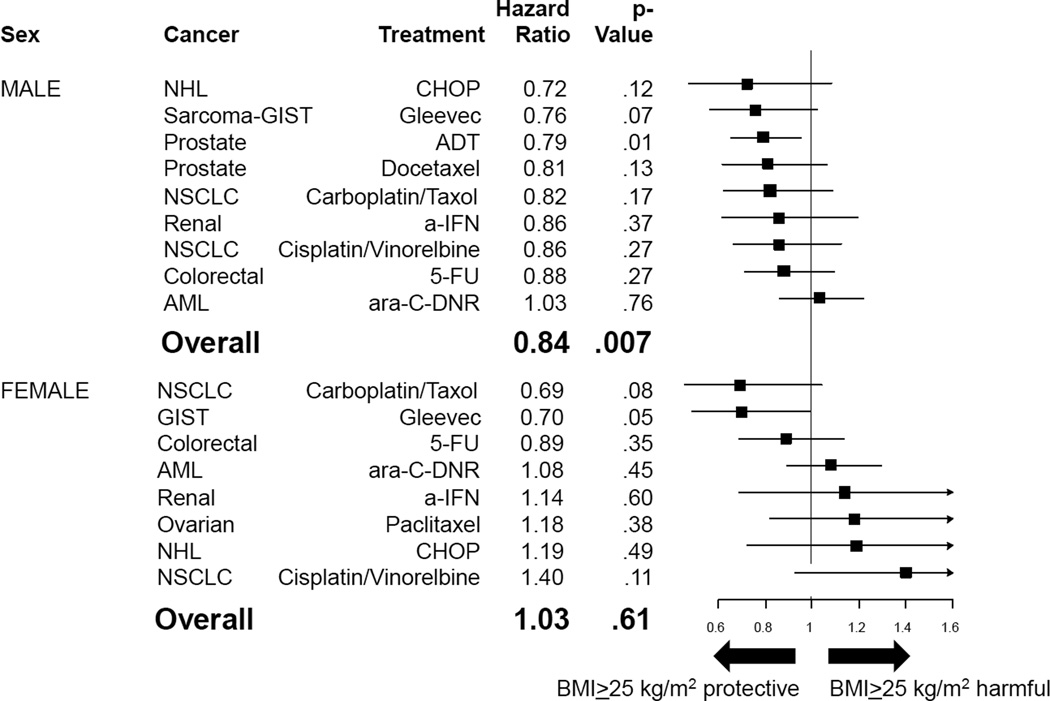

Patterns of Overall Survival by Sex

Figure 4, panel A, illustrates forest plots for the association of BMI and overall survival grouped by sex. For males, elevated BMI tended to be protective for overall survival (mean HR=0.82, p=.003), and for females, elevated BMI tended to be neither protective nor harmful for overall survival (mean HR=1.04, p=.86). Results within male and female subgroups were similar when the analysis was limited only to regimens with dose based on body surface area (BSA) (Figure 4, panel B) and when sex-specific analyses were excluded (Figure 4, panel C).

Figure 4. Association of BMI and Overall Survival, By Sex and Regimens, Based on BMI=25 kg/m2 Cutpoint.

Forest plots displaying hazard ratio (HR) estimates across 14 different cancer and treatment combinations. HR <1 indicates that BMI ≥25 kg/m2 is associated with decreased risk of death, while HR >1 indicates that BMI ≤25 kg/m2 is associated with increased risk of death. Panel A displays forest plots by sex; Panel B displays analyses restricted to treatment regimens using doses based upon body surface area, by sex; and Panel C displays analyses excluding sex-specific analyses, by sex.

Abbreviations: 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; a-IFN, interferon alpha; AC, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ara-C, cytarabine; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin, and prednisone; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; DNR, daunorubicin; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; P, paclitaxel

Survival Patterns Conditioned on Surviving 1 Year

We examined the survival patterns among patients who survived ≥1 year (Supplemental Figure 1, panel A). There was no evidence that BMI≥25 kg/m2 at baseline was better or worse among those who survived ≥1 year. The mean hazard ratio was 1.01 (p=.20). Similar to the analyses in all patients, there appeared to be sex-specific variation in the hazard ratio patterns. We further examined the interaction of BMI and sex among those who survived one year (Supplemental Figure 1, panels B and C). Consistent with analyses presented above, elevated BMI was protective on average for males (mean HR=0.85, p=.03) and neither protective nor harmful for females (mean HR=1.19, p=.21).

Survival Patterns by Obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2) Status

In order to understand the associations between being obese at diagnosis and cancer survival, we also examined patterns of survival based on a BMI cutpoint of 30 kg/m2. Obese patients had an elevated risk of death among those treated with cytarabine and daunorubicin for acute myelogenous leukemia (HR=1.18, p=.02) and those treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil for breast cancer (HR=1.34, p=.03). In no other cancer/treatment combinations was elevated BMI associated with a statistically significantly higher or lower risk of death (Supplemental Figure 2). The overall mean hazard ratio across all cohorts was 1.00, indicating no evidence of a trend towards higher or lower risk of death across these 14 groups of trials (p=.71).

We examined whether patterns of survival according to a BMI cutpoint of 30 kg/m2 differed by patient sex. In a similar fashion as observed for a BMI cutpoint of 25 kg/m2, obesity was associated with better overall survival for males (mean HR=0.88, p=.04) but neither better nor worse overall survival for females (mean HR=1.05, p=.28; Supplemental Figure 3, panel A). These results were generally consistent within male and female subgroups when the analysis was limited only to regimens with dose based on BSA (Supplemental Figure 3, panel B) and when sex-specific analyses were excluded (Supplemental Figure 4).

Survival among Patients with Advanced Cancer

In order to remove the possibility that cancer stage confounded the association between BMI and survival, we restricted the analyses to patients with advanced stage cancers. In these analyses the results were consistent with the earlier analyses showing that among men, BMI≥25 kg/m2 was protective (mean HR=0.84, p=.007) and among women, there was no association between the BMI cutpoint and overall survival (mean HR 1.03, p=.61) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Association of BMI and Overall Survival, Advanced Cancers Only, Based on BMI=25 kg/m2 Cutpoint.

Forest plots displaying hazard ratio (HR) estimates across 14 different cancer and treatment combinations, restricting analyses to patients with advanced cancers. HR <1 indicates that BMI ≥25 kg/m2 is associated with decreased risk of death, while HR >1 indicates that BMI ≤25 kg/m2 is associated with increased risk of death. Panel A displays forest plots restricted to men and Panel B displays analyses restricted to women.

Abbreviations: 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; a-IFN, interferon alpha; AC, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ara-C, cytarabine; BCG, bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BMI, body mass index; CAF, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-fluorouracil; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, oncovin, and prednisone; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; DNR, daunorubicin; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; P, paclitaxel

DISCUSSION

In an analysis of 22 clinical trials representing 14 different cancer/treatment combinations, the association between BMI and survival was not consistent across cancer type or stage. There was no statistically significant evidence that BMI at a cutpoint of 25 kg/m2 was associated with overall survival. However, there was good evidence that the relationship between BMI and cancer survival differed by sex. On average, elevated BMI was associated with better overall survival in males, but neither better nor worse overall survival in females. This association was maintained when sex-specific cancers were excluded, when treatment regimens were restricted to dose based on BSA, and when early stage cancers were excluded. The results remained consistent when a BMI cutpoint of 30 kg/m2 was examined and when analyses were restricted to individuals who survived at least one year following trial enrollment. The latter analysis emphasizes the potentially durable impact of BMI on long-term survival.

The majority of cancers included in this analysis were of advanced stage. The literature on the association between BMI and survival among individuals with advanced staged cancers is sparse and inconsistent. One reason for the inconsistency may be due to the timing of BMI assessment. A prior meta-analysis shows that timing of BMI assessment affects observed associations between BMI and colorectal cancer survival (23). Our analysis uses BMI data collected at trial enrollment, which is advantageous because it allows for examination of BMI as a prognostic factor assessed prior to treatment.

We observed no association between BMI and cancer survival among breast cancer patients, which is somewhat inconsistent with prior studies that reported an inverse association between BMI at breast cancer diagnosis and survival (3, 5, 11). However, each of the individual breast cancer trials included in this analysis showed a non-significant relationship in the same direction as prior studies. It is possible that the use of cutpoints at 25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2 masked the potential association of very high (class II or III) obesity and worse survival, as suggested by an observational study in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project, which showed an association of BMI and survival when class II or III obesity was attained (24). It is further possible that our analysis was underpowered, and that a meta-analysis would be needed to better define this association.

We observed that men with advanced prostate cancer who had a higher BMI at trial enrollment had better survival. These results are inconsistent with some prior observational studies where higher BMI among prostate cancer patients was associated with poorer survival (6, 7, 25). It should be noted that in our analyses the trial of androgen deprivation therapy and the trial of chemotherapy for hormone refractory prostate cancer both had similar findings, raising the possibility that the mechanism by which BMI affects survival may be independent of treatment effects. Prior studies have shown that obese patients with prostate cancer may be underdosed (26), which could account for poorer survival. However this is unlikely to be the explanation for our findings as underdosing would be uncommon in the clinical trial setting.

Perhaps our most provocative finding is that baseline BMI had a different association with survival for female and male patients. The finding held after removing potential confounding factors from the analyses, including sex-specific cancers, treatments not dosed on BSA, and early stage cancers that may have had a better prognosis. Differences between sexes may be related to differences in the biology of the disease, or may be related to chemotherapy dosing, distribution or tolerance. The role of muscle may be important in explaining sex differences. Prior studies have shown that muscle mass is associated with better cancer prognosis (27, 28). The ratio of muscle to fat is higher for men than women at each BMI category (29, 30), which may explain in part the interaction between sex and BMI with respect to survival outcomes. These differences need to be explored in future investigations.

A strength of this analysis is the systematic examination of the relationship between baseline BMI and survival across multiple cancer types and stages using a consistent analytic approach. As all participants were enrolled in a therapeutic clinical trial, and each cancer-drug combination was analyzed separately, the study design removes course of treatment as a prognostic factor and potential confounder. Prior studies have noted that choice of BMI cutpoints and categories affects study results and inferences (31, 32). We used an innovative method to identify a meaningful analytical cutpoint to discriminate between BMI groups. The finding with respect to better overall survival for elevated BMI patients in males was remarkably consistent, regardless of which subsets of studies were examined. Despite these strengths, there are also limitations. We do not have data on BMI prior to diagnosis, during treatment, or in the post treatment phase. These measures collected systematically would allow for a better understanding of whether change in weight following diagnosis is associated with cancer prognosis. The analyses also do not account for lifestyle behaviors or circumstances that could affect the relationship between BMI and survival, and we had no data on comorbidities or body composition. These measures would allow for better understanding of potential targets for modifiable behaviors and risk factors. We do not have data on breast cancer subtypes, which has been associated with prognosis (2, 33). It is possible as well that some of the individual analyses were underpowered to detect differences between BMI groups. Our analysis was based on comparing two groups of patients based on specified single cutpoints. However, it is possible that more complicated relationships between BMI and survival exist (such as a quadratic or U-shaped relationship using multiple cutpoints). Finally, since these are trial patients, compared to non-trial patients they likely have fewer comorbid conditions, especially severe comorbidities and end-organ damage, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings.

These findings should be considered within the context of findings on BMI and overall mortality risk in the general population. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data show a U-shaped association between BMI and overall mortality (32, 34). Overweight status is associated with the lowest risk of mortality, Grade 1 obesity (BMI 30–35 kg/m2) is unassociated with mortality and underweight and Grades 2 (BMI 35–40 kg/m2) and 3 (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) (32, 34) are associated with higher mortality. Furthermore, the risk associated with obesity was found to be age dependent, with the effect of obesity on mortality being lower among older individuals. There has been a great deal of discussion on how to interpret these findings; one issue is the possibility that illness-related weight loss may bias observational studies (35–37). Analyses of men from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging find that weight loss prior to death begins 9 years before death and for cancer deaths weight loss accelerated significantly 3 years prior to death (38). Therefore it is possible that prior to enrollment into the trials analyzed here, subjects at highest risk of mortality were already experiencing weight loss. Another issue to be considered is that obesity is associated with co-morbidities that may have excluded subjects from entering the trials and that the obese individuals entering the trials may have been systematically healthier for non-cancer risks than obese individuals overall.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) and American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) guidelines for cancer survivors recommend being as lean as possible without being underweight (39, 40). Our findings are observational and therefore do not provide definitive proof that BMI is causally related to cancer survival. Nonetheless, our findings – for men in particular – are inconsistent with this recommendation. In fact, these results suggest that recommendations for body size and weight management following a cancer diagnosis may be disease, stage, and even gender specific. The ACS and AICR guidelines are intended to apply across all cancer types, and are based upon hypothesized carcinogenesis mechanisms related to hormonal, inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways. Our results suggest that more tailored recommendations may be in order. This could be particularly true in cancers with long survival times, wherein patients may be at risk for other BMI-associated diseases, including cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Studies are needed to test the effects of weight management strategies in specific high-risk patient populations.

In summary, our findings suggest that the association between BMI and cancer survival is not consistent across all cancer types and stage, and that sex-related factors may interact with BMI and affect cancer survival. Higher BMI at the time of a cancer diagnosis may be protective for men. Among women there was much more variability in the association between BMI and overall survival. These findings suggest that the effect of BMI may be different for different cancer types, and that body size recommendations for cancer survivors that are disease, stage and gender specific may be warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the patients who participated in the SWOG trials and the clinical research staff who facilitated their participation.

Financial Support: National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (K23 CA141052 to H. Greenlee and 1UG1CA189974-01 to J.M. Unger, M. LeBlanc, S. Ramsey, D.L. Hershman)

Footnotes

Previous Presentations: A portion of these data were presented in a poster presentation at the 13th Annual AACR International Conference on Frontiers in Cancer Prevention, New Orleans, LA, September 2014.

Disclaimers: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sparano JA, Wang M, Zhao F, Stearns V, Martino S, Ligibel JA, et al. Obesity at diagnosis is associated with inferior outcomes in hormone receptor-positive operable breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5937–5946. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crozier JA, Moreno-Aspitia A, Ballman KV, Dueck AC, Pockaj BA, Perez EA. Effect of body mass index on tumor characteristics and disease-free survival in patients from the HER2-positive adjuvant trastuzumab trial N9831. Cancer. 2013;119:2447–2454. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Azambuja E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Francis P, Quinaux E, Crown JA, Vicente M, et al. The effect of body mass index on overall and disease-free survival in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with docetaxel and doxorubicin-containing adjuvant chemotherapy: the experience of the BIG 02-98 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontanella C, Lederer B, Gade S, Vanoppen M, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, et al. Impact of body mass index on neoadjuvant treatment outcome: a pooled analysis of eight prospective neoadjuvant breast cancer trials. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:127–139. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright ME, Chang S-C, Schatzkin A, Albanes D, Kipnis V, Mouw T, et al. Prospective study of adiposity and weight change in relation to prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer. 2007;109:675–684. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez C, Patel AV, Calle EE, Jacobs EJ, Chao A, Thun MJ. Body mass index, height, and prostate cancer mortality in two large cohorts of adult men in the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2001;10:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson SO, Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Adami HO, Engholm G, Englund A, et al. Body size and prostate cancer: a 20-year follow-up study among 135006 Swedish construction workers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89:385–389. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.5.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiu BC-H, Gapstur SM, Greenland P, Wang R, Dyer A. Body mass index, abnormal glucose metabolism, and mortality from hematopoietic cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:2348–2354. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyengar NM, Kochhar A, Morris PG, Morris LG, Zhou XK, Ghossein RA, et al. Impact of obesity on the survival of patients with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. Cancer. 2014;120:983–991. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tait S, Pacheco J, Gao F, Bumb C, Ellis M, Ma C. Body mass index, diabetes, and triple-negative breast cancer prognosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasenda B, Bass A, Koeberle D, Pestalozzi B, Borner M, Herrmann R, et al. Survival in overweight patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: a multicentre cohort study. BMC cancer. 2014;14:728. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi Y, Kim T-Y, Lee K-h, Han S-W, Oh D-Y, Im S-A, et al. The impact of body mass index dynamics on survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Chlebowski R, LaMonte MJ, Bea JW, Qi L, Wallace R, et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and mortality in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer: Results from the Women's Health Initiative. Gynecologic Oncology. 2014;133:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelser C, Arem H, Pfeiffer RM, Elena JW, Alfano CM, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Prediagnostic lifestyle factors and survival after colon and rectal cancer diagnosis in the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer. 2014;120:1540–1547. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi Y, Correa AM, Hofstetter WL, Vaporciyan AA, Rice DC, Walsh GL, et al. The influence of high body mass index on the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer after surgery as primary therapy. Cancer. 2010;116:5619–5627. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunner AM, Sadrzadeh H, Feng Y, Drapkin BJ, Ballen KK, Attar EC, et al. Association between baseline body mass index and overall survival among patients over age 60 with acute myeloid leukemia. American Journal of Hematology. 2013;88:642–646. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beason TS, Chang S-H, Sanfilippo KM, Luo S, Colditz GA, Vij R, et al. Influence of body mass index on survival in veterans with multiple myeloma. The Oncologist. 2013;18:1074–1079. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karnell LH, Sperry SM, Anderson CM, Pagedar NA. Influence of body composition on survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Head & neck. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hed.23983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, Statistical methodology. 1972;34:187-. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unger JM, Barlow WE, Martin DP, Ramsey SD, Leblanc M, Etzioni R, et al. Comparison of survival outcomes among cancer patients treated in and out of clinical trials. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju002. dju002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S, Liu J, Wang X, Li M, Gan Y, Tang Y. Association of obesity and overweight with overall survival in colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis of 29 studies. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2014;25:1489–1502. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0450-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwan ML, Chen WY, Kroenke CH, Weltzien EK, Beasley JM, Nechuta SJ, et al. Pre-diagnosis body mass index and survival after breast cancer in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:729–739. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moller H, Roswall N, Van Hemelrijck M, Larsen SB, Cuzick J, Holmberg L, et al. Prostate cancer incidence, clinical stage and survival in relation to obesity: a prospective cohort study in Denmark. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2015;136:1940–1647. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith MR. Obesity and sex steroids during gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment for prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:241–245. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Versteeg KS, de van der Schueren MA, den Braver NR, Berkhof J, Langius JA, et al. Loss of Muscle Mass During Chemotherapy Is Predictive for Poor Survival of Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shachar SS, Williams GR, Muss HB, Nishijima TF. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: A meta-analysis and systematic review. European journal of cancer. 2016;57:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallagher D, Visser M, De Meersman RE, Sepulveda D, Baumgartner RN, Pierson RN, et al. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: effects of age, gender, and ethnicity. Journal of applied physiology. 1997;83:229–239. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, Ross R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. Journal of applied physiology. 2000;89:81–88. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Graubard BI. Body mass index categories in observational studies of weight and risk of death. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;180:288–296. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwan ML, John EM, Caan BJ, Lee VS, Bernstein L, Cheng I, et al. Obesity and mortality after breast cancer by race/ethnicity: The California Breast Cancer Survivorship Consortium. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;179:95–111. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309:71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg J. Underweight, overweight, obesity, and excess deaths. JAMA. 2005;294:552. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.552-a. author reply-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strickler HD, Hall C, Wylie-Rosett J, Rohan T. Underweight, overweight, obesity, and excess deaths. JAMA. 2005;294:551–552. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.551-b. author reply 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willett WC, Hu FB, Colditz GA, Manson JE. Underweight, overweight, obesity, and excess deaths. JAMA. 2005;294:551. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.551-a. author reply 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alley DE, Metter EJ, Griswold ME, Harris TB, Simonsick EM, Longo DL, et al. Changes in weight at the end of life: characterizing weight loss by time to death in a cohort study of older men. American journal of epidemiology. 2010;172:558–565. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Institute for Cancer Research. Recommendations for Cancer Prevention. [May 1, 2013];2013 Available from: http://preventcancer.aicr.org/site/PageServer?pagename=recommendations_home. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bandera EV, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:30–67. doi: 10.3322/caac.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.