Abstract

AIM

To identify health and psychosocial problems associated with bullying victimization and conduct a meta-analysis summarizing the causal evidence.

METHODS

A systematic review was conducted using PubMed, EMBASE, ERIC and PsycINFO electronic databases up to 28 February 2015. The study included published longitudinal and cross-sectional articles that examined health and psychosocial consequences of bullying victimization. All meta-analyses were based on quality-effects models. Evidence for causality was assessed using Bradford Hill criteria and the grading system developed by the World Cancer Research Fund.

RESULTS

Out of 317 articles assessed for eligibility, 165 satisfied the predetermined inclusion criteria for meta-analysis. Statistically significant associations were observed between bullying victimization and a wide range of adverse health and psychosocial problems. The evidence was strongest for causal associations between bullying victimization and mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, poor general health and suicidal ideation and behaviours. Probable causal associations existed between bullying victimization and tobacco and illicit drug use.

CONCLUSION

Strong evidence exists for a causal relationship between bullying victimization, mental health problems and substance use. Evidence also exists for associations between bullying victimization and other adverse health and psychosocial problems, however, there is insufficient evidence to conclude causality. The strong evidence that bullying victimization is causative of mental illness highlights the need for schools to implement effective interventions to address bullying behaviours.

Keywords: Bullying, Victimization, Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Child, Adolescent

Core tip: There is convincing evidence of a causal association between exposure to bullying victimization in children and adolescents and adverse health outcomes including anxiety, depression, poor mental health, poor general health, non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. It is probable that bullying victimization also causes an increased risk of cigarette smoking and illicit drug use. This review highlights that bullying victimization is associated with a wide and diverse range of problems and reinforces the need for effective interventions to be implemented in schools to address the high prevalence of children and adolescents engaging in bullying behaviours.

INTRODUCTION

Bullying victimization among children and adolescents is a global public health issue, well-recognised as a behaviour associated with poor adjustment in youth[1]. There is evidence suggesting bullying victimization in children and adolescents has enduring effects which may persist into adulthood[2-4]. Bullying victimization is most commonly defined as exposure to negative actions repeatedly and over time from one or more people, and involves a power imbalance between the perpetrator(s) and the victim[5]. Traditional bullying includes physical contact (pushing, hitting) as well as verbal harassment (name calling, verbal taunting), rumour spreading, intentionally excluding a person from a group, and obscene gestures. In recent years cyberbullying has emerged as a significant public health problem[5-8].

The estimated prevalence of bullying victimization is wide-ranging, with 10% and 35% of adolescents experiencing recurrent bullying victimization[9-16]. While contextual and cultural differences influence prevalence estimates[17], this variation is most frequently explained by differences in measurement strategy[18-20]. As a result, researchers continue to call for greater consensus in the definition and measurement of bullying behaviours[17,21,22]. Cook et al[17] examined the variability in prevalence of bullying victimization in a meta-analysis, and more recently Modecki et al[20] synthesised studies measuring both traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Mean prevalence was 36% for traditional bullying victimization and 15% for cyberbullying victimization[20]. There was significant overlap between bullying victimization in traditional and online settings[20]. A meta-analysis by Kowalski et al[23] showed that the strongest predictor of cyber-victimization was traditional bullying victimization.

Many studies have examined adverse health and psychosocial problems associated with bullying victimization. Those most commonly reported are mental health problems, specifically depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicidal behaviour[2,14,24-28]. Over the past two decades researchers have conducted a number of systematic reviews to examine the relationship between bullying victimization and ill mental health.

The first systematic investigation by Hawker and Boulton[1] was a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies of peer victimization published between 1978 and 1997. The authors reported victimization was significantly associated with depression, loneliness, reduced self-esteem and self-concept, as well as anxiety. To understand the temporal sequence between peer victimization and mental health problems, Reijntjes and colleagues conducted a pair of meta-analyses of longitudinal studies to examine internalizing (depression, anxiety, withdrawal, loneliness, and somatic complaints) and externalizing behaviours (aggression and delinquency) and peer victimization[29,30]. They examined two prospective paths: (1) peer victimization at baseline and changes in internalizing and externalizing problems at a second time point; and (2) internalizing and externalizing problems at baseline and changes in peer victimization at follow-up. The two meta-analyses demonstrated internalizing and externalizing behaviours are both antecedents and consequences of bullying victimization[29,30].

Another meta-analytic review on bullying victimization and depression by Ttofi et al[31] found those children who were bullied at school were twice as likely to develop depression compared to those who had not been bullied. In addition, another meta-analytic review found those children involved in any bullying behaviour were more likely to develop psychosomatic problems[32]. Finally, three systematic reviews have shown an association between bullying victimization and increased risk of adolescent suicidal ideation and behaviours[33-35].

In contrast to mental health, there is mixed evidence for the relationship between bullying victimization and substance use. Some studies report that bullying victimization is associated with a reduced risk of engaging in harmful alcohol use in later life[16,28], whereas others suggest that being bullied may result in an increased probability of later harmful alcohol use[36,37]. Similarly, some studies have shown an association between being bullied and later illicit drug use and smoking[36-39], whereas others have found no association at all[2,14,24,40].

The association between bullying victimization and psychosocial problems, such as academic achievement and school functioning/connectedness and criminal behaviour has also been examined. A meta-analysis by Nakamoto and Schwartz[41] found a small but significant negative association between bullying victimization and academic achievement. However, Kowalski et al[23] found no significant relationship between cyberbullying victimization and academic achievement. Another study found those exposed to bullying victimization in adolescence were at increased risk of involvement in criminal behaviour such as carrying a weapon[40].

There are now a large number of studies examining associations between bullying victimization and a wide range of adverse health and psychosocial problems. However, many of these have not been systematically examined and many existing systematic reviews did not include cyberbullying. Furthermore, although associations exist, it is unclear if there is a causal relationship. It is plausible that there are common factors that predispose individuals to being bullied in childhood but independently also increase the risk of adverse health and other psychosocial problems. Rigorous appraisal is required to consider both the possibility of a causal association but also other plausible explanations for any significant associations. Given the variation between studies, this study aimed to investigate adverse outcomes of both traditional and cyber bullying victimization and conduct a meta-analysis to summarize each association. Furthermore, we critically evaluated whether sufficient evidence existed to establish a causal relationship between bullying victimization and each of the adverse health and psychosocial problems. This is the first study to complete a summary of the evidence for all adverse health and psychosocial problems that are potentially a consequence of traditional and cyber bullying victimization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study followed the recommendations from the PRISMA 2009 revision[42] and the guidelines outlined by the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology[43] (Supplementary material S1). Methods and inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified in advance in the review protocol (Supplementary material S2).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis included studies meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) reported original, empirical research published in a peer reviewed journal; (2) examined the relationship between exposure to bullying victimization as a child or adolescent and one or more consequences of the bullying exposure; and (3) is a population based study. This study did not examine a particular type of bullying victimization therefore all direct and indirect forms of bullying including cyberbullying were included. Included studies reported odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) comparing those exposed to bullying victimization and those not exposed to bullying victimization or, alternatively, provided information from which effect sizes (ORs and CIs) could be calculated between those exposed to bullying victimization and an outcome.

Search strategy

Four electronic databases (PsycINFO, ERIC, EMBASE and PubMed) were used to search for literature on the adverse correlates of bullying victimization as either a child or adolescent from inception up to 28 February 2015. The search was not restricted to the English language nor by any other means. The searches of the databases were conducted using the terms: “bullying”, “bullied”, “harassment”, “intimidation”, “victimization” along with “child” and “adolescent”. As this study aimed to examine all correlates that were potentially a consequence of bullying victimization, the search terms used in conjunction with those above were broader terms such as “outcome” “harm” “consequence” and “risk”. In addition, reference lists of selected studies were screened for any other relevant study and articles in languages other than English were translated (Supplementary material S2).

Data collection and quality assessment

The full text of articles that met all inclusion criteria were retrieved and examined. Data extracted using a data extraction template included publication details, country where study was conducted, methodological characteristics such as sample size and study design, exposure and outcome measures, type of bullying and frequency (Supplementary material S2). Each study was then subjected to a quality assessment in order for the reviewers to rate the quality of each study. Two reviewers independently reviewed the included articles and completed the quality assessment and any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. The quality assessment tool was based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of observational studies[44] as used by Norman et al[45] (Supplementary material S2).

Statistical analysis

Following the method used by Norman et al[45], MetaXL version 2.1[46], an add-in for Microsoft Excel was used in this study to conduct the meta-analysis. ORs were chosen as the summary measure. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics[47]. This meta-analysis used a quality effects model[48], a modified version of the fixed-effects inverse variance model that additionally allows greater weight to be given to studies of higher quality vs studies of lesser quality. The quality effects model avoids the limitation in random-effects models of returning to equal weighting irrespective of sample size if heterogeneity is large[47,48]. Furthermore, in order to address the effects of important study characteristics and explore heterogeneity this study conducted subgroup analyses, dependent on data availability, for sex of participants in the sample, geographic location and income level (high income vs low-to-middle income as per the World Bank classification criteria), severity of the bullying (frequent - at least once a month, vs sometimes - less than once a month), age of bullying victimization (before 13 years of age vs after 13 years of age), and type of study (prospective vs cross-sectional).

RESULTS

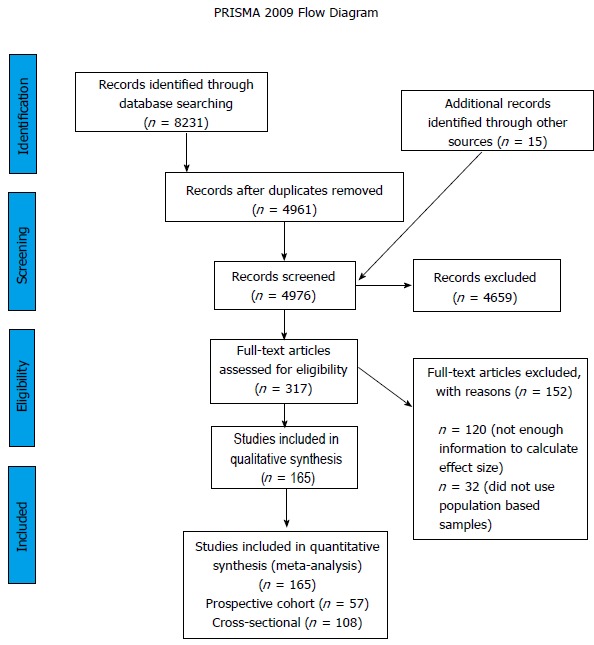

A total of 8231 articles were primarily identified by the search, of which 3270 were duplicates. Titles and abstracts for the 4961 remaining unduplicated references were reviewed and 15 additional articles were found from reference lists. From reviewing the title and abstracts a further 4659 articles were excluded. This left 317 articles meeting the following criteria: (1) original research extracted from a peer reviewed journal; and (2) examined the bullying victimization as a child or adolescent and one or more outcomes. Of the 317 articles reviewed, a further 152 articles were excluded as they did not use a population based sample or did not report enough information to calculate an effect size. The remaining 165 articles provided evidence of an effect size for bullying victimization and an outcome (Figure 1) - either odds ratio with confidence intervals or provided data which enabled the calculation of effect sizes. The majority (n = 142) were from high income regions. There were far fewer studies (n = 22) from low- and middle-income countries, and only one study utilized cross-national samples from different income-level countries. Of the articles included, 57 had a prospective cohort design and the remaining 108 were cross-sectional. The majority of studies measured self-reported bullying victimization. Some were from samples collected from a state or regions where as others were nationally representative (Supplementary material S3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing process of study selection for inclusion in systematic review and meta-analyses.

Bullying victimization in children and adolescents and mental health

Bullying victimization in children and adolescents was associated with a wide range of adverse mental health outcomes (Table 1) including poor mental health (OR = 1.60; 95%CI: 1.42-1.81), syndromes such as depression and anxiety, and symptoms and behaviours such as psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation and attempts. Specifically, those exposed to bullying victimization had an increased risk of depression (OR = 2.21; 95%CI: 1.34-3.65). This association remained significant for all the sub-group analyses including prospective studies, age bullying occurred, sex and severity of the bullying. A dose response existed between being “sometimes bullied” and “frequently bullied” and depression (OR = 1.78; 95%CI: 1.39-2.28 and OR = 3.26; 95%CI: 2.45-4.34 respectively). In comparing high- and low-to-middle income countries, there was no significant difference in the odds of developing depression. Those exposed to bullying victimization were significantly more likely to experience anxiety (OR = 1.77; 95%CI: 1.34-2.33) and exposure to bullying victimization was associated with a wide range of anxiety spectrum disorders such as social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder. This association remained after conducting subgroup analyses including study type, sex and severity of the bullying; however, the association between bullying victimization and anxiety was not significant in children under 13 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Associations between bullying victimization in children and adolescents and mental health outcomes

| Data points | Pooled OR | 95%CI lower bound | 95%CI upper bound | Cochran’s Q | I² (%) | Test for heterogeneity (P value) | |

| Poor mental health | |||||||

| Pooling all | 39 | 1.6 | 1.42 | 1.81 | 303.79 | 87.49 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 25 | 1.8 | 1.44 | 2.25 | 211.78 | 88.67 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 14 | 1.39 | 1.29 | 1.49 | 22.12 | 41.24 | 0.05 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 3 | 2.49 | 1.86 | 3.32 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Female | 3 | 2.38 | 1.41 | 4 | 6.95 | 71.22 | 0.03 |

| Twins | 3 | 1.41 | 1.27 | 1.56 | 2.5 | 20.09 | 0.29 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 8 | 1.5 | 1.27 | 1.76 | 47.68 | 85.23 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 8 | 1.52 | 1.18 | 1.95 | 51.4 | 86.38 | < 0.01 |

| Anxiety | |||||||

| Pooling all | 58 | 1.77 | 1.34 | 2.33 | 3816.23 | 98.51 | < 0.01 |

| Anxiety | 32 | 1.56 | 1.39 | 1.75 | 434.61 | 92.87 | < 0.01 |

| Social phobia | 8 | 2.48 | 1.59 | 3.86 | 11.01 | 36.41 | 0.14 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 2 | 2.83 | 1.38 | 5.84 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.74 |

| PTSD | 12 | 6.41 | 1.93 | 21.22 | 497.11 | 97.79 | < 0.01 |

| Specific phobia | 1 | 2.4 | 1 | 5.6 | - | - | - |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 1 | 4.6 | 2 | 10.6 | - | - | - |

| Panic disorder | 1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 6.5 | - | - | - |

| Agoraphobia | 1 | 4.6 | 1.7 | 12.5 | - | - | - |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 39 | 2.02 | 1.21 | 3.38 | 3697.48 | 98.97 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 19 | 1.29 | 1.06 | 1.55 | 84.03 | 78.58 | < 0.01 |

| Age of bullying | |||||||

| Less than 13 yr | 13 | 1.4 | 0.58 | 3.41 | 123.12 | 90.25 | < 0.01 |

| Older than 13 yr | 45 | 1.81 | 1.29 | 2.56 | 3688.82 | 98.81 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 16 | 1.84 | 1.3 | 2.59 | 112.23 | 86.63 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 15 | 2.46 | 1.74 | 3.48 | 124.39 | 88.74 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 7 | 1.46 | 1.06 | 2 | 43.41 | 86.18 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 25 | 2.47 | 1.94 | 3.14 | 122.47 | 80.4 | < 0.01 |

| Geographic location and income level | |||||||

| Low-to-middle income | 22 | 2.41 | 1.75 | 3.32 | 175.97 | 88.07 | < 0.01 |

| High income | 36 | 1.67 | 1.24 | 2.25 | 3441.17 | 98.98 | < 0.01 |

| Depression | |||||||

| Pooling all | 92 | 2.21 | 1.34 | 3.65 | 14525.32 | 99.37 | < 0.01 |

| Major depressive disorder | 2 | 2.27 | 0.68 | 7.57 | 2.07 | 51.63 | 0.15 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 63 | 1.95 | 1.24 | 3.07 | 2594.97 | 97.61 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 29 | 3.03 | 1.31 | 6.98 | 4583.05 | 99.39 | < 0.01 |

| Age of bullying | |||||||

| Less than 13 yr | 36 | 2.11 | 1.63 | 2.72 | 544.9 | 93.58 | < 0.01 |

| Older than 13 yr | 56 | 2.29 | 1.24 | 4.23 | 13806.72 | 99.6 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 27 | 2.07 | 1.48 | 2.89 | 443.84 | 94.14 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 21 | 2.13 | 1.18 | 3.86 | 313.5 | 93.62 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 15 | 1.78 | 1.39 | 2.28 | 78.61 | 82.19 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 28 | 3.26 | 2.45 | 4.34 | 224.43 | 87.97 | < 0.01 |

| Geographic location and income level | |||||||

| Low-to-middle income | 13 | 2.53 | 1.75 | 3.68 | 143.98 | 91.67 | < 0.01 |

| High income | 79 | 2.15 | 1.26 | 3.68 | 14351.72 | 99.46 | < 0.01 |

| Psychotic symptoms | |||||||

| Specific psychiatric symptoms | 6 | 2.07 | 1.49 | 2.87 | 20.57 | 75.69 | < 0.01 |

| Non-clinical psychotic experiences | 9 | 2.68 | 2.03 | 3.54 | 15.1 | 47.03 | 0.06 |

| Psychotic symptoms | 5 | 2.73 | 1.97 | 3.77 | 10.86 | 63.16 | 0.03 |

| Personality disorders | |||||||

| Anti-social personality disorder | 2 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 2.28 | 2.53 | 60.48 | 0.11 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 3 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 3.46 | 4.8 | 58.31 | 0.09 |

| Eating disorders | |||||||

| Bulimia nervosa | 1 | 3 | 1.4 | 6.2 | - | - | - |

| Anorexia nervosa | 1 | 0.004 | 0 | 251 | - | - | - |

| Non-suicidal self injury | |||||||

| Pooling all | 30 | 1.75 | 1.4 | 2.19 | 749.02 | 96.13 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 21 | 1.55 | 1.09 | 2.22 | 721.15 | 97.23 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 9 | 1.65 | 1.34 | 2.02 | 19.39 | 58.75 | 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 6 | 4.86 | 3.35 | 7.07 | 13.56 | 63.12 | 0.02 |

| Female | 4 | 2.7 | 2 | 3.65 | 8.92 | 66.37 | 0.03 |

| Twins | 2 | 2.57 | 1.79 | 3.7 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.73 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 6 | 1.57 | 1.09 | 2.25 | 34.04 | 85.31 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 7 | 2.52 | 1.6 | 3.97 | 54.49 | 88.99 | < 0.01 |

| Suicidal ideation | |||||||

| Pooling all | 105 | 1.77 | 1.56 | 2.02 | 2093.5 | 95.03 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 86 | 1.8 | 1.56 | 2.09 | 2037.46 | 95.83 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 19 | 1.68 | 1.38 | 2.05 | 38.98 | 53.82 | < 0.01 |

| Age of bullying | |||||||

| Less than 13 yr | 22 | 1.85 | 1.48 | 2.3 | 74.4 | 71.77 | < 0.01 |

| Older than 13 yr | 83 | 1.75 | 1.51 | 2.03 | 1984.06 | 95.87 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 21 | 1.95 | 1.64 | 2.32 | 76.6 | 73.89 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 18 | 2.15 | 1.84 | 2.52 | 33.15 | 48.72 | 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 16 | 1.53 | 1.28 | 1.82 | 35.19 | 57.38 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 21 | 2.59 | 2.06 | 3.25 | 49.83 | 59.87 | < 0.01 |

| Geographic location and income level | |||||||

| Low-to-middle income | 11 | 1.31 | 1.06 | 1.61 | 60.02 | 83.34 | < 0.01 |

| High income | 94 | 1.8 | 1.43 | 2.26 | 1894.91 | 95.09 | < 0.01 |

| Suicide attempt | |||||||

| Pooling all | 48 | 2.13 | 1.66 | 2.73 | 1110.46 | 95.77 | < 0.01 |

| Suicidal attempt/non-suicidal self injury | 3 | 2.97 | 1.68 | 5.23 | 6.33 | 68.42 | 0.04 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 40 | 2.03 | 1.46 | 2.84 | 1105.65 | 96.47 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 8 | 2.04 | 1.38 | 3.01 | 4.34 | 0 | 0.74 |

| Age of bullying | |||||||

| Less than 13 yr | 11 | 2.11 | 1.65 | 2.69 | 11.49 | 12.98 | 0.32 |

| Older than 13 yr | 37 | 1.52 | 0.82 | 2.83 | 579.75 | 93.79 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 7 | 2.93 | 1.65 | 5.18 | 15.38 | 54.5 | 0.02 |

| Female | 7 | 2.89 | 1.52 | 5.49 | 24.23 | 71.11 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 9 | 2.19 | 1.71 | 2.8 | 7.52 | 0 | 0.48 |

| Frequent | 12 | 3.77 | 2.55 | 5.58 | 28.31 | 61.14 | < 0.01 |

| Geographic location and income level | |||||||

| Low-to-middle income | 4 | 1.91 | 1.07 | 3.43 | 22.18 | 86.47 | < 0.01 |

| High income | 44 | 2.17 | 1.69 | 2.8 | 1084.61 | 96.04 | < 0.01 |

| Behavioural problems | |||||||

| Pooling all | 54 | 1.37 | 1.18 | 1.59 | 862.4 | 93.85 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 29 | 1.18 | 0.99 | 1.41 | 311.21 | 91 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 25 | 1.56 | 0.94 | 2.58 | 413.53 | 94.2 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 9 | 1.35 | 0.68 | 2.67 | 450.06 | 98.22 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 7 | 1.99 | 0.97 | 4.1 | 88.07 | 93.19 | < 0.01 |

| Twins | 2 | 1.19 | 0.94 | 1.5 | 7.31 | 86.31 | 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 8 | 1.95 | 0.92 | 4.1 | 243.71 | 97.13 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 8 | 2.26 | 0.76 | 6.69 | 163.51 | 95.72 | < 0.01 |

| Externalising behaviours | 20 | 1.29 | 1.12 | 1.5 | 157.09 | 87.9 | < 0.01 |

| Delinquent/deviant behaviour | 24 | 1.99 | 1.24 | 3.2 | 423.78 | 94.57 | < 0.01 |

| Missed school | 7 | 1.49 | 0.99 | 2.23 | 38.4 | 84.37 | < 0.01 |

| Disruptive behavioural disorders | |||||||

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 1 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 8.5 | - | - | - |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.5 | - | - | - |

| Conduct disorder | 1 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 8.8 | - | - | - |

| Other mental health outcomes (not included above) | |||||||

| Nervousness | 9 | 1.82 | 1.51 | 2.2 | 135.59 | 94.1 | < 0.01 |

| Powerlessness | 2 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 1.64 | 39.18 | 0.2 |

| Feeling low | 7 | 2.26 | 1.66 | 3.08 | 299.47 | 98 | < 0.01 |

| Irritability or bad temper | 7 | 1.82 | 1.51 | 2.2 | 125.07 | 95.2 | < 0.01 |

| Feel helpless | 5 | 3.2 | 2.01 | 5.09 | 273.51 | 98.54 | < 0.01 |

| Feeling tense | 3 | 3.07 | 2.06 | 4.56 | 3.02 | 33.75 | 0.22 |

| Unhappy/sad | 12 | 1.25 | 0.55 | 2.84 | 668.61 | 98.35 | < 0.01 |

| Worried | 4 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 1.47 | 314.35 | 99.05 | < 0.01 |

| Afraid | 3 | 2.68 | 1.18 | 6.09 | 9.49 | 78.92 | 0.01 |

Bullying victimization was also associated with non-suicidal self-injury (OR = 1.75; 95%CI: 1.40-2.19) and increased risk of suicidal ideation (OR = 1.77; 95%CI: 1.56-2.02) and the association remained significant for all subgroup analyses (Table 1). A dose response existed between being “sometimes bullied” and “frequently bullied” and suicide ideation (OR = 1.53; 95%CI: 1.28-1.82 and OR = 2.59; 95%CI: 2.06-3.25 respectively). Bullying victimization was associated with an increase in suicide attempts (OR = 2.13; 95%CI: 1.66-2.73). Subgroup analysis showed both males and females were approximately three times more likely to attempt suicide if they were bullied (OR = 2.93; 95%CI: 1.65-5.18 and OR = 2.89; 95%CI: 1.52-5.49 respectively). There was nearly a fourfold increase in suicide attempts for individuals who experienced frequent bullying victimization (OR = 3.77; 95%CI: 2.55-5.58) (Table 1). When comparing high income countries to those with low and middle income, the odds of bullying victims developing suicidal ideation or attempting suicide were similar.

Although bullying victimization in children and adolescents was associated with the pooling of all behavioural problems (OR = 1.37; 95%CI: 1.18-1.59), this association was not significant in prospective cohort studies and no dose-response was observed. Diagnoses of disruptive behavioural disorders were not associated with bullying victimization in children and adolescents (Table 1).

Bullying victimization in children and adolescents and substance use

Table 2 presents the associations between bullying victimization and substance use. When all studies were pooled together there was a significant association between bullying victimization and alcohol use (OR = 1.26; 95%CI: 1.00-1.58). A subgroup analysis showed a significant association between bullying victimization and the risk of tobacco use for prospective studies (OR = 1.62; 95%CI: 1.31-1.99). Furthermore, a dose response was present with frequent bullying victimization being associated with tobacco use (OR = 3.19; 95%CI: 1.19-8.58), whereas no significant association was found with those who were “sometimes bullied” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between bullying victimization in children and adolescents and substance use

| Data points | Pooled OR | 95%CI lower bound | 95%CI upper bound | Cochran’s Q | I² (%) | Test for heterogeneity (P value) | |

| Alcohol use | |||||||

| Pooling all | 53 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 1.58 | 10328.18 | 99.5 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 38 | 1.28 | 0.88 | 1.84 | 10256.15 | 99.64 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 15 | 1.19 | 0.87 | 1.62 | 67.87 | 79.37 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 6 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 4.89 | 0.00 | 0.43 |

| Female | 4 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 1.57 | 6.36 | 52.86 | 0.1 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 6 | 1.72 | 0.84 | 3.50 | 86.17 | 94.20 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 13 | 1.53 | 0.78 | 3.03 | 332.27 | 96.39 | < 0.01 |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | |||||||

| Sometimes | 24 | 1.52 | 1.08 | 2.13 | 8416.94 | 99.73 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 29 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 1.14 | 251.81 | 88.88 | < 0.01 |

| Age of bullying | |||||||

| Less than 13 yr | 16 | 1.23 | 0.93 | 1.63 | 1618.14 | 99.07 | < 0.01 |

| Older than 13 yr | 37 | 1.31 | 0.96 | 1.80 | 6896.71 | 99.48 | < 0.01 |

| Geographic location and income level | |||||||

| Low-to-middle income | 11 | 1.37 | 0.75 | 2.49 | 8328.21 | 99.88 | < 0.01 |

| High income | 42 | 1.08 | 0.91 | 1.27 | 462.84 | 91.14 | < 0.01 |

| Tobacco use | |||||||

| Pooling all | 35 | 1.36 | 0.96 | 1.92 | 418.71 | 91.88 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 26 | 1.17 | 0.59 | 2.31 | 394.92 | 93.67 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 9 | 1.62 | 1.31 | 1.99 | 11.48 | 30.33 | 0.18 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 3 | 0.97 | 0.59 | 1.58 | 8.23 | 75.7 | 0.02 |

| Female | 3 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.68 | 1.78 | 0 | 0.41 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 4 | 1.89 | 0.83 | 4.33 | 71.38 | 95.8 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 4 | 3.19 | 1.19 | 8.58 | 39.85 | 92.47 | < 0.01 |

| Frequency of smoking | |||||||

| Sometimes | 28 | 1.36 | 0.89 | 2.06 | 400.72 | 93.26 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 7 | 1.35 | 1.00 | 1.84 | 16.28 | 63.16 | 0.01 |

| Illicit drug use | |||||||

| Pooling all | 34 | 1.41 | 1.10 | 1.81 | 677.62 | 95.13 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 11 | 2.43 | 1.42 | 4.15 | 297.3 | 96.64 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 23 | 1.27 | 1.12 | 1.44 | 67.23 | 67.28 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 7 | 1.04 | 0.81 | 1.33 | 32.84 | 81.73 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 5 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.33 | 3.26 | 0.00 | 0.52 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 7 | 1.22 | 0.78 | 1.90 | 160.47 | 96.26 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 8 | 1.14 | 0.43 | 3.00 | 465.43 | 98.50 | < 0.01 |

| Geographic location and income level | |||||||

| Low-to-middle income | 5 | 4.05 | 2.18 | 7.55 | 98.61 | 95.94 | < 0.01 |

| High income | 29 | 1.31 | 1.15 | 1.48 | 103.73 | 73.01 | < 0.01 |

| Cannabis only all | 9 | 1.42 | 0.96 | 2.12 | 23.32 | 65.70 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 1 | 2.46 | 1.53 | 3.95 | - | - | - |

| Prospective cohort | 8 | 1.36 | 0.90 | 2.05 | 18.14 | 61.41 | 0.01 |

Bullying victimization was associated with an increased risk of illicit drug use (OR = 1.41; 95%CI: 1.10-1.81). Subgroup analysis revealed that the association between bullying victimization and increased risk of using illicit drugs was significant in both cross-sectional (OR = 2.43; 95%CI: 1.42-4.15) and prospective studies (OR = 1.27; 95%CI: 1.12-1.44). A subgroup analysis also revealed bullying victims in low-to-middle income countries are at an increased risk of illicit drug use (OR = 4.05; 95%CI: 2.18-7.55) compared with bullying victims in high income countries (OR = 1.31; 95%CI: 1.15-1.48). No significant association was found in a sub group analysis examining cannabis and bullying victimization in children and adolescence (Table 2).

Bullying victimization in children and adolescents and other health outcomes

Table 3 presents the association between bullying victimization and other health outcomes. Bullying victimization was associated with increased risk of somatic symptoms, the most common being stomach ache (OR = 1.76; 95%CI: 1.53-2.03), sleeping difficulties (OR = 1.73; 95%CI: 1.46-2.05), headaches (OR = 1.64; 95%CI: 1.38-1.94), dizziness (OR = 1.64; 95%CI: 1.38-1.95), and back pain (OR = 1.67; 95%CI: 1.43-1.95). Bullying victimization was also associated with an increased risk of being overweight and obese (OR = 1.68; 95%CI: 1.21-2.33 and OR = 1.78; 95%CI: 1.42-2.21, respectively). These associations were significant for cross-sectional studies only and there was no dose response.

Table 3.

Associations between bullying victimization in children and adolescents and other health outcomes

| Data points | Pooled OR | 95%CI lower bound | 95%CI upper bound | Cochran’s Q | I² (%) | Test for heterogeneity (P value) | |

| Somatic symptoms | |||||||

| Unspecified psychosomatic symptoms | 25 | 2.00 | 1.54 | 2.60 | 232.02 | 89.66 | < 0.01 |

| Stomach ache | 25 | 1.76 | 1.53 | 2.03 | 138.73 | 82.7 | < 0.01 |

| Sleeping difficulties | 24 | 1.73 | 1.46 | 2.05 | 574.91 | 96 | < 0.01 |

| Headache | 26 | 1.64 | 1.38 | 1.94 | 169.16 | 85.22 | < 0.01 |

| Bedwetting | 3 | 2.51 | 1.44 | 4.37 | 4.93 | 59.45 | 0.08 |

| Feeling tired | 2 | 2.68 | 1.39 | 5.19 | 1.22 | 17.87 | 0.27 |

| Poor appetite | 2 | 2.23 | 1.60 | 3.12 | 0 | 0 | 0.95 |

| Back pain | 8 | 1.67 | 1.43 | 1.95 | 73.53 | 90.48 | < 0.01 |

| Skin problems | 1 | 1.82 | 1.33 | 251 | - | - | - |

| Dizziness | 9 | 1.64 | 1.38 | 1.95 | 76.57 | 89.55 | < 0.01 |

| Eating and weight related problems | |||||||

| Binge eating | 2 | 2.66 | 1.68 | 4.22 | 0.57 | 0 | 0.45 |

| Non-diet soft drink consumption | 1 | 1.21 | 1.04 | 1.41 | - | - | - |

| Skips breakfast | 6 | 1.41 | 1.20 | 1.65 | 11.89 | 57.94 | 0.04 |

| Underweight | |||||||

| Pooling all | 2 | 1.27 | 0.73 | 2.21 | 0 | 0 | 0.96 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1 | 1.28 | 0.69 | 2.37 | - | - | - |

| Female | 1 | 1.24 | 0.19 | 2.29 | - | - | - |

| Overweight | |||||||

| Pooling all | 14 | 1.68 | 1.21 | 2.33 | 82.69 | 84.28 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross- sectional | 12 | 1.99 | 1.39 | 2.85 | 65.45 | 83.19 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 2 | 0.98 | 0.64 | 1.49 | 1.92 | 47.97 | 0.17 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 7 | 1.22 | 0.99 | 1.49 | 8.04 | 25.4 | 0.23 |

| Female | 7 | 2.22 | 1.28 | 3.84 | 50.17 | 88.04 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 2 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 1.74 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.77 |

| Frequent | 6 | 1.14 | 0.88 | 1.47 | 7.37 | 32.2 | 0.19 |

| Obese | |||||||

| Pooling all | 13 | 1.78 | 1.42 | 2.21 | 14.68 | 18.28 | 0.26 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 10 | 1.97 | 1.53 | 2.53 | 7.22 | 0 | 0.61 |

| Prospective cohort | 3 | 1.57 | 0.89 | 2.77 | 6.89 | 70.97 | 0.03 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 6 | 1.94 | 1.45 | 2.60 | 4.88 | 0 | 0.43 |

| Female | 6 | 2.15 | 1.57 | 2.94 | 2.22 | 0 | 0.82 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 2 | 1.63 | 1.11 | 2.38 | 0.52 | 0 | 0.47 |

| Frequent | 6 | 2.09 | 1.59 | 2.75 | 5.26 | 4.86 | 0.39 |

| Sexual behaviour problems | |||||||

| Teen parent | 5 | 1.26 | 0.81 | 1.97 | 15.11 | 73.53 | < 0.01 |

| Risky sexual behaviour | 4 | 2.28 | 0.95 | 5.48 | 23.43 | 87.2 | < 0.01 |

| Early onset of sexual activities | 3 | 1.44 | 0.90 | 2.30 | 7.38 | 72.91 | 0.02 |

| Pooling all | 12 | 1.51 | 1.01 | 2.25 | 85.66 | 87.16 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 3 | 1.77 | 0.42 | 7.52 | 54.97 | 96.36 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 9 | 1.34 | 0.98 | 1.84 | 23.88 | 66.51 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 2 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 1.28 | 2.46 | 59.32 | 0.12 |

| Frequent | 4 | 2.38 | 1.05 | 5.41 | 27.55 | 89.11 | < 0.01 |

| Health services utilised | |||||||

| Pooling all | 16 | 1.20 | 0.99 | 1.45 | 34.37 | 56.36 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 14 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.39 | 27.91 | 53.42 | 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 2 | 1.54 | 0.65 | 3.61 | 4.43 | 77.43 | 0.04 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 7 | 1.17 | 0.95 | 1.43 | 3.54 | 0 | 0.74 |

| Female | 7 | 1.41 | 1.12 | 1.77 | 11.16 | 46.25 | 0.08 |

| General medication use | |||||||

| Pooling all | 12 | 1.16 | 0.80 | 1.70 | 117.98 | 90.68 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 11 | 0.99 | 0.56 | 1.75 | 112.26 | 91.09 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 1 | 1.67 | 1.09 | 2.58 | - | - | - |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | |||||||

| Medication for headache | 2 | 1.43 | 1.06 | 1.93 | 2.34 | 57.21 | 0.13 |

| Medication for stomach-ache | 2 | 1.09 | 0.72 | 1.65 | 1.9 | 47.5 | 0.17 |

| Female | |||||||

| Medication for headache | 2 | 1.19 | 0.98 | 1.45 | 1.33 | 24.79 | 0.25 |

| Medication for stomach-ache | 2 | 1.23 | 1.01 | 1.5 | 0.27 | 0 | 0.61 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 5 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 1.59 | 15.46 | 74.13 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 5 | 1.72 | 1.11 | 2.67 | 24.9 | 83.93 | < 0.01 |

| Over the counter drug misuse | 3 | 0.95 | 0.19 | 4.66 | 76.34 | 97.38 | < 0.01 |

| Psychotropic medication use | |||||||

| Pooling all | 13 | 1.28 | 0.72 | 2.26 | 205.76 | 94.17 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 11 | 0.95 | 0.32 | 2.8 | 195.34 | 94.88 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 2 | 1.31 | 0.66 | 2.6 | 5.61 | 82.18 | 0.02 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | |||||||

| Medication for nervousness | 2 | 1.32 | 0.42 | 4.1 | 14.98 | 93.32 | < 0.01 |

| Medication for sleeping | 2 | 1.89 | 1.33 | 2.67 | 1.59 | 37.28 | 0.21 |

| Female | |||||||

| Medication for nervousness | 2 | 1.97 | 1.49 | 2.59 | 1.06 | 5.88 | 0.3 |

| Medication for sleeping | 2 | 1.83 | 1.42 | 2.36 | 0.27 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 6 | 1.66 | 1.26 | 2.18 | 18.54 | 73.04 | < 0.01 |

| Frequent | 6 | 1.88 | 1.17 | 3.03 | 31.93 | 84.34 | < 0.01 |

| Prescription drug misuse | 3 | 0.92 | 0.17 | 5.07 | 88.16 | 97.73 | < 0.01 |

| Poor general health | |||||||

| Pooling all | 29 | 1.83 | 1.45 | 2.31 | 133.31 | 79 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 22 | 1.71 | 1.21 | 2.42 | 112.06 | 81.26 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 7 | 1.56 | 1.07 | 2.28 | 19.72 | 69.57 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 9 | 1.95 | 1.16 | 3.27 | 20.5 | 60.98 | 0.01 |

| Female | 9 | 2.36 | 1.11 | 5.04 | 52.78 | 84.84 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 4 | 2.16 | 1.10 | 4.26 | 9.15 | 67.21 | 0.03 |

| Frequent | 4 | 6.96 | 2.17 | 22.35 | 16.72 | 82.05 | < 0.01 |

When all studies were pooled, bullying victimization in children and adolescents was associated with increased risk of sexual behaviour problems (OR = 1.51; 95%CI: 1.01-2.25) which included teenage pregnancy, early onset of sexual activities and risky sexual behaviour. Subgroup analyses were not significant with the exception of those frequently bullied. Although bullying victimization was associated with increased likelihood of poor general health (OR = 1.83; 95%CI: 1.45-2.31) and this association persisted when restricted to prospective cohort studies (OR = 1.56; 95%CI: 1.07-2.28). There was no consistent increase in utilisation of health services or medications in those exposed to bullying victimization during childhood or adolescence (Table 3).

Bullying victimization in children and adolescents and academic and social functioning

The association between bullying victimization and functioning at school was inconsistent. There was a robust association between bullying victimization in childhood or adolescence and poor academic achievement. Those who had exposure to bullying victimization were more likely to have poor academic achievement (OR = 1.33; 95%CI: 1.06-1.66), whilst those with good academic achievement were less likely to have been exposed to bullying victimization (OR = 0.71; 95%CI: 0.60-0.85); however, all studies except one were cross-sectional. Bullying victimization was not associated with later financial or occupational functioning.

Similarly, there were inconsistent associations between bullying victimization and social problems. Those exposed were approximately twice as likely to report loneliness (OR = 1.89; 95%CI: 1.39-2.57) and poor life satisfaction (OR = 2.26; 95%CI: 1.41-3.60) and were significantly less likely to have a good quality of life (OR = 0.85; 95%CI: 0.78-0.93). Bullying victimization was not consistently associated with low self-esteem, social problems, or criminal behaviours (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between bullying victimization and academic and social functioning

| Data points | Pooled OR | 95%CI lower bound | 95%CI upper bound | Cochran’s Q | I² (%) | Test for heterogeneity (P value) | |

| Poor school functioning | |||||||

| Pooling all | 6 | 1.10 | 0.87 | 1.38 | 82 | 93.9 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 3 | 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.27 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.85 |

| Prospective cohort | 3 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 1.08 | 8.15 | 75.46 | 0.02 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 1 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.04 | - | - | - |

| Frequent | 1 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 1.19 | - | - | - |

| Academic achievement | |||||||

| Poor academic achievement | |||||||

| Pooling all | 6 | 1.33 | 1.06 | 1.66 | 11.17 | 55.25 | 0.02 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 6 | 1.33 | 1.06 | 1.66 | 11.17 | 55.25 | 0.02 |

| Good academic achievement | |||||||

| Pooling all | 4 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.85 | 8.81 | 65.97 | 0.07 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 3 | 0.86 | 0.8 | 0.92 | 2.89 | 30.69 | 0.58 |

| Prospective cohort | 1 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.76 | - | - | - |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 1.74 | 2.49 | 59.8 | 0.65 |

| Female | 2 | 1.32 | 0.99 | 1.75 | 1.4 | 28.7 | 0.84 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 1 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.93 | - | - | - |

| Frequent | 1 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.93 | - | - | - |

| Poor financial and occupational functioning | |||||||

| Pooling all prospective cohort | 16 | 1.14 | 0.87 | 1.50 | 92.97 | 83.86 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 3 | 1.00 | 0.9 | 1.11 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.98 |

| Frequent | 3 | 0.81 | 0.61 | 1.07 | 2.68 | 25.32 | 0.26 |

| Social isolation | |||||||

| Loneliness | |||||||

| Pooling all | 13 | 1.89 | 1.39 | 2.57 | 3120.66 | 99.62 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 13 | 1.89 | 1.39 | 2.57 | 3120.66 | 99.62 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 4 | 2.58 | 1.62 | 4.10 | 222.21 | 98.65 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 3 | 3.92 | 1.95 | 7.90 | 19.53 | 89.76 | < 0.01 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 2 | 2.09 | 1.98 | 2.20 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.53 |

| Frequent | 4 | 4.12 | 2.24 | 7.60 | 23.32 | 87.13 | < 0.01 |

| Self esteem | |||||||

| Pooling all | 14 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 93.73 | 86.13 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 4 | 1.13 | 0.83 | 1.54 | 76.58 | 96.08 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 10 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 12.32 | 26.93 | 0.2 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 5 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.06 | 20.65 | 80.63 | < 0.01 |

| Female | 4 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 1.03 | 5.74 | 47.7 | 0.13 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 5 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.61 | 0 | 0.81 |

| Frequent | 5 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.04 | 9.65 | 58.54 | 0.05 |

| Social problems | |||||||

| Pooling all | 22 | 1.02 | 0.74 | 1.42 | 427.13 | 95.08 | < 0.01 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 5 | 2.86 | 1.42 | 5.76 | 38.09 | 89.5 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 17 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 1.06 | 72.36 | 77.89 | < 0.01 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1 | 2.89 | 1.45 | 5.73 | - | - | - |

| Female | 1 | 8.10 | 4.60 | 14.26 | - | - | - |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 3 | 0.9 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.78 |

| Frequent | 3 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 3.67 | 45.49 | 0.16 |

| Criminal behaviour | |||||||

| Pooling all | 33 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 1.39 | 133.36 | 76.01 | < 0.01 |

| Carrying a weapon | 8 | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.98 | 19.16 | 63.47 | 0.01 |

| Violent offense/behaviour | 6 | 1.25 | 1.01 | 1.56 | 2.46 | 0 | 0.78 |

| Study type | |||||||

| Retrospective/cross-sectional | 9 | 1.01 | 0.47 | 2.14 | 106.83 | 92.51 | < 0.01 |

| Prospective cohort | 24 | 1.05 | 0.92 | 1.19 | 25.72 | 10.58 | 0.31 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 11 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.22 | 13.78 | 27.43 | 0.18 |

| Female | 4 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 1.04 | 0.38 | 0 | 0.94 |

| Severity of bullying | |||||||

| Sometimes | 5 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 1.26 | 7.37 | 45.74 | 0.12 |

| Frequent | 8 | 1.22 | 0.86 | 1.74 | 16.33 | 57.13 | 0.02 |

| Other outcomes reported | |||||||

| Good quality of later life | 6 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 17.42 | 71.29 | < 0.01 |

| Poor life satisfaction | 6 | 2.26 | 1.41 | 3.60 | 3.79 | 0 | 0.58 |

| Problematic internet usage | 1 | 2.36 | 1.58 | 3.54 | - | - | - |

| Picked on by siblings | 1 | 1.69 | 1.38 | 2.07 | - | - | - |

DISCUSSION

This paper provides the most comprehensive critical analysis of the association between bullying victimization and a wide range of health and psychosocial problems. The primary and sub-group analyses allow for interpretation of the evidence of causality within the Bradford-Hill Framework, based on the following: Biological plausibility, the temporal relationship of the association, strength and consistency of the association, the presence of a dose-response relationship, and whether an alternate explanation for the associations is possible[49]. We used the grading system developed by the World Cancer Research Fund[50] as used in the Global Burden of Disease study as a guideline for evaluation of the level of evidence.

Temporality

In this meta-analysis, both longitudinal (n = 57) and cross-sectional (n = 108) studies showed associations between bullying victimization and many adverse health and psychosocial problems. Prospective studies provided evidence of a temporal relationship showing bullying victimization preceded the later adverse consequences.

A temporal relationship exists between bullying victimization and outcomes such as anxiety, depression, non-suicidal self-injury, suicide ideation and suicide attempts. As poor mental health is also a known risk factor for bullying victimization[51], it is with caution we say that an independent temporal relationship exists between bullying victimization and these adverse mental health outcomes. Many studies did not control for pre-existing mental health and could be reporting a continuation of pre-existing psychopathology and not a direct outcome of the bullying victimization. Nonetheless, two recent studies have found that even when controlling for pre-existing mental health, bullying victimization was strongly associated with later adverse mental health consequences such as non-suicidal self-injury and depression[27,28].

Strength of the association

Both prospective and population-based studies demonstrated significant associations between bullying victimization and adverse health and psychosocial problems. After adjusting for confounding variables, there was generally a reduction in the strength of these associations. Furthermore, the magnitude of the associations diverged depending on the sub-group analysis performed. Despite some variability, bullying victimization was found to significantly increase the likelihood of mental ill health suggesting significant and robust associations.

Consistency of the association

Consistency of the associations between bullying victimization and mental ill health was demonstrated in the estimated effect sizes across studies. It is possible that publication bias affected the results for some of the outcomes. Direction of the association (as estimated through risk estimates) was consistent across different geographic regions, samples, study designs, and income levels investigated, particularly for anxiety, depression, non-suicidal self-injury, suicide ideation and suicide attempts (Supplementary material Figures S4, S5, S7, S8, S9). Inconsistent associations were observed for certain outcomes such as behavioural problems (Supplementaty material Figure S6).

Dose-response relationship

Available evidence suggests that experiencing more severe or frequent forms of adversity in childhood increases the risk of adverse outcomes compared to a lower exposure to adversity[45,52-56], particularly for mental health problems. Similarly, this study demonstrated a dose-response relationship between bullying victimization and detrimental effects on health, in particular for mental health problems. After summarizing the evidence through a meta-analysis, dose-response relationships were observed between bullying victimization and depression, suicide ideation, cigarette smoking and loneliness[45,52-56]. An increase in the dose of bullying victimization (frequent vs sometimes) resulted in non-significantly greater point estimates for other problems such as anxiety, medication use (general and psychotropic), suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury.

Plausibility

Due to a lack of animal models, the majority of inferences for biological plausibility arise from observational rather than experimental data. However, one model of social defeat in rats has been used to understand bullying victimization[57,58]. Two male rats are placed into a cage together, and after fighting, one rat becomes dominant and the other subordinate. The subordinate rat experiences social defeat and after a single experience demonstrates signs of stress. One study found that the subordinate rat demonstrated behaviours representative of depression in humans when exposed to multiple social defeats over several weeks[59].

Observational data has also been used to explain the association between bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence and the later development of mental health problems. First, early adverse experiences (i.e., bullying victimization) that occur during vulnerable developmental periods can cause neurobiological[60,61] or inflammatory[62] changes expressed as illnesses in later life[61]. Moreover, those individuals exposed to frequent bullying victimization who develop mental health problems may self-medicate their distress and negative emotions with alcohol, illicit drugs, medications, tobacco or disengaging from school.

Taking into account both the limited animal studies[57-59] and observational studies[60-62], it can be understood as to why bullying victimization can affect the immediate and long-term health and non-health related outcomes of the individual.

Consideration of alternate explanations

The relationship between bullying victimization and adverse health and psychosocial problems are thought to be complex and influenced by both genetics and environmental factors; however, there are limited twin studies available to inform these associations[27,63-66]. One study[64] found that being bullied in childhood is an environmentally mediated contributing factor to poor childhood mental health. Another found victimized twins were more likely to self-harm than their non-victimized twin sibling[27]. Exposure to bullying victimization has also been found to be associated with socioeconomic status[51,67] which is also known to play a role in the development of mental health problems and other health and non-health related outcomes[68].

It is further acknowledged that the association between bullying victimization and adverse outcomes is not necessarily an independent relationship. As early emotional and behavioural problems are known risk factors for bullying victimization, without adequate statistical adjustment, some studies may risk reporting pre-existing psychopathology rather than a direct outcome of bullying. The available evidence suggests a complex relationship between genetics and environment and neither can solely explain the relationship between bullying victimization and adverse outcomes. Even though some of the effects of bullying victimization on adverse outcomes reported may be a result of confounding factors, generally the association with mental health problems was significant after controlling for potential confounding factors.

Assessment of causality

Using the grading system developed by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF)[50] as a guideline for evaluation of the level of evidence, we concluded that there was “convincing evidence” for a causal relationship between bullying victimization and anxiety, depression, poor general and mental health, non-suicidal self-injury, suicide attempts, and suicide ideation. This evidence was based on a substantial number of epidemiological studies identified in this systematic review including prospective observational studies of sufficient size, duration, and quality showing consistent effects. In addition, the association was considered biologically plausible. We concluded that “probable evidence” of a causal relationship existed between exposure to bullying victimization and illicit drug and tobacco use based on the epidemiological evidence. Possible causal associations existed between bullying victimization and lower academic achievement, alcohol use, loneliness, obesity, overweight and psychosomatic symptoms. This evidence was based mainly on findings from cross-sectional studies and a few prospective studies showing inconsistent associations between exposure and disease. More studies are needed to support these tentative associations, which are also considered to be biologically plausible.

All other significant associations reported in this study were classified as having insufficient evidence of a causal relationship (Table 5). This is not suggesting that there is no causal relationship. Further research is needed to better examine if any associations that exist are causal or due to other confounding factors. Furthermore, the use of WCRF grading system, although appropriate for dietary risk factors, might not be adequate for psychosocial factors particularly newly emerging risks.

Table 5.

Strength of evidence for a causal relationship between bullying victimization and adverse health or psychosocial problems

| Strength of evidence | Adverse health or psychosocial problem |

| Convincing | Anxiety; depression; poor mental health; poor general health; non-suicidal self-injury; suicide attempts; suicide ideation |

| Probable | Tobacco use; illicit drug use |

| Possible | Alcohol use; psychotic symptoms; increased use of health services in females; lower academic achievement; social isolation; loneliness; psychosomatic symptoms, overweight and obesity |

| Insufficient | Binge eating; bulimia nervosa; borderline personality disorder; behavioural problems; carrying a weapon; general medication use; health services sought; poor financial and occupational functioning; psychotropic medication use; poor school functioning; sexual behavioural problems; poor life satisfaction |

Limitations

While we followed rigorous methodological steps, some limitations are notable. As studies with non-significant findings are less likely to be published, there may be a publication bias within this meta-analysis resulting in the association between bullying victimization and some adverse outcomes being overstated[69,70]. Additionally, inconsistencies would have occurred in the analysis due to methodological differences in the way bullying victimization is defined and measured throughout the studies as there is no consensus on the best way to measure bullying victimization[18,19]. In order to address this, a quality effects model was used giving higher scores to those studies which provided respondents with a definition and utilised a validated measure of bullying. There are also methodological issues in regards to the adverse outcomes reported, as some have been self-reported, while others were reported by teachers, parents, clinicians or through objective measures. This issue was also addressed with the use of a quality effects model in which higher quality scores were given to those studies where standardised validated diagnostic instruments were used to assess the outcome relative to those where outcomes were self-reported on a non-validated scale[44]. In spite of this methodology, the assessment of exposure to bullying and the assessment of a wide range of outcomes remains a challenge. In particular, there will always be some uncertainty pertaining to the measurement of bullying, especially when retrospectively reported as a result of the respondent’s subjective perception of the actions and behaviours of others.

As a research question involving bullying victimization can only be observational and not experimental, a further limitation of this meta-analysis are those limitations that come with observational studies[71]. First, we acknowledge the issue of confounding. It is appropriate to adjust for these confounders in the statistical analyses by either stratification or multivariate analysis[71]. Although many studies controlled for socio-demographic and other variables[2,27], some reported unadjusted odds ratios between bullying victimization and adverse outcomes, or provided only basic adjustment for sex and age[72,73]. This was addressed in this meta-analysis through the use of the quality score of studies where confounding factors were not adequately adjusted and by conducting further analyses where data were available[44]. Generally, after controlling for the effects of confounding variables, the associations between bullying victimization and adverse outcomes were attenuated. The majority of studies included in this meta-analysis did not identify individuals who were both victims and perpetrators of bullying. Previous research has suggested those who are both perpetrators and victims are at even greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes[28]; however, we were unable to confirm this with the current study.

In the majority of primary analyses of the association between bullying victimization and adverse outcomes, significant heterogeneity was present. This heterogeneity remained significant in most subgroup analyses even after controlling for study quality in the quality effects models[44].

In conclusion, evidence suggests a causal relationship between bullying victimization and mental health outcomes. There were also associations between bullying victimization and other adverse health and psychosocial problems which require further research to accurately measure the negative impact of bullying victimization and the broad health and economic costs. Through the implementation of school wide interventions that involve the entire school community (i.e., staff, students, and parents) bullying behaviour is considered a modifiable risk factor[25,74]. This review highlights the increased likelihood of a wide and diverse range of problems that are experienced by those exposed to bullying victimization. These findings reinforce the need for implementation of effective interventions in schools to address the high prevalence of children and adolescents engaging in bullying behaviours.

COMMENTS

Background

Bullying victimization (including traditional and cyberbullying) among children and adolescents is a global public health issue, well-recognised as a behaviour associated with poor adjustment in youth. There is evidence suggesting bullying victimization in children and adolescents has enduring effects which may persist into adulthood.

Research frontiers

There have been many studies examining the association between bullying victimization in children and adolescents and adverse health and social problems. However, many of these have not been systematically examined and existing systematic reviews did not include cyberbullying. Furthermore, although associations exist, it is unclear if there is a causal relationship.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between bullying victimization in children and adolescents and adverse health outcomes including anxiety, depression, poor mental health, poor general health, non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. It is probable that bullying victimization also causes an increased risk of cigarette smoking and illicit drug use.

Applications

Given the convincing evidence of a causal association, there is an urgent need for effective interventions to be implemented in schools to address the high prevalence of children and adolescents engaging in bullying behaviours.

Peer-review

This is an important topic on consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence. This area for sure needs more attention. The authors have done a great job presenting a large systematic review and meta-analysis of studies correlating the history of bullying victimization with different mental health problems in childhood and adolescence.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement: No additional data is available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: September 14, 2016

First decision: October 21, 2016

Article in press: December 28, 2016

P- Reviewer: Alavi N, Classen CF S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, Costello EJ. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:419–426. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takizawa R, Maughan B, Arseneault L. Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:777–784. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigurdson JF, Undheim AM, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Sund AM. The long-term effects of being bullied or a bully in adolescence on externalizing and internalizing mental health problems in adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9:42. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0075-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olweus D. Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:1171–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Ikonen M, Lindroos J, Luntamo T, Koskelainen M, Ristkari T, Helenius H. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: a population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:720–728. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross D, Shaw T, Hearn L, Epstein M, Monks H, Lester L, Thomas L. Australian covert bullying prevalence study (ACBPS). Perth, Australia Child Health Promotion Research Centre, Edith Cowan University. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen PW, Verlinden M, Dommisse-van Berkel A, Mieloo C, van der Ende J, Veenstra R, Verhulst FC, Jansen W, Tiemeier H. Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: do family and school neighbourhood socioeconomic status matter? BMC Public Health. 2012;12:494. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rigby K, Slee PT. Bullying among Australian school children: reported behavior and attitudes toward victims. J Soc Psychol. 1991;131:615–627. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1991.9924646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solberg ME, Olweus D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggress Behav. 2003;29:239–268. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Due P, Holstein BE, Soc MS. Bullying victimization among 13 to 15-year-old school children: results from two comparative studies in 66 countries and regions. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20:209–221. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sourander A, Jensen P, Rönning JA, Niemelä S, Helenius H, Sillanmäki L, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, et al. What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:397–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemphill SA, Kotevski A, Herrenkohl TI, Bond L, Kim MJ, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF. Longitudinal consequences of adolescent bullying perpetration and victimisation: a study of students in Victoria, Australia. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2011;21:107–116. doi: 10.1002/cbm.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook CR, Williams KR, Guerra NG, Kim TE. Variability in the prevalence of bullying and victimization: A cross-national and methodological analysis. In: Jimerson SR, Swearer S, Espelage Dorothy L, editors. Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective. New York: Routledge; 2010. pp. 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin RS, Gross AM. Childhood bullying: Current empirical findings and future directions for research. Aggress Violent Beh. 2004;9:379–400. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw T, Dooley JJ, Cross D, Zubrick SR, Waters S. The Forms of Bullying Scale (FBS): validity and reliability estimates for a measure of bullying victimization and perpetration in adolescence. Psychol Assess. 2013;25:1045–1057. doi: 10.1037/a0032955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, Runions KC. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas HJ, Connor JP, Scott JG. Integrating traditional bullying and cyberbullying: Challenges of definition and measurement in adolescents - a review. Educ Psychol Rev. 2015;27:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ybarra ML, Boyd D, Korchmaros JD, Oppenheim JK. Defining and measuring cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying victimization. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1073–1137. doi: 10.1037/a0035618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coomber K, Toumbourou JW, Miller P, Staiger PK, Hemphill SA, Catalano RF. Rural adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use: a comparison of students in Victoria, Australia, and Washington State, United States. J Rural Health. 2011;27:409–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vreeman RC, Carroll AE. A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:78–88. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klomek AB, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K, Piha J, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Almqvist F, Gould MS. Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. J Affect Disord. 2008;109:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher HL, Moffitt TE, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Arseneault L, Caspi A. Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2683. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore SE, Norman RE, Sly PD, Whitehouse AJ, Zubrick SR, Scott J. Adolescent peer aggression and its association with mental health and substance use in an Australian cohort. J Adolesc. 2014;37:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Boelen PA, van der Schoot M, Telch MJ. Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis. Aggress Behav. 2011;37:215–222. doi: 10.1002/ab.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F, Loeber R. Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies. J Aggress Confl Peace Res. 2011;3:63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gini G, Pozzoli T. Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1059–1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holt MK, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Polanin JR, Holland KM, DeGue S, Matjasko JL, Wolfe M, Reid G. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e496–e509. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J. Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:435–442. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YS, Leventhal B. Bullying and suicide. A review. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20:133–154. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2009;34:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goebert D, Else I, Matsu C, Chung-Do J, Chang JY. The impact of cyberbullying on substance use and mental health in a multiethnic sample. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1282–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0672-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niemelä S, Brunstein-Klomek A, Sillanmäki L, Helenius H, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Moilanen I, Tamminen T, Almqvist F, Sourander A. Childhood bullying behaviors at age eight and substance use at age 18 among males. A nationwide prospective study. Addict Behav. 2011;36:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vieno A, Gini G, Santinello M. Different forms of bullying and their association to smoking and drinking behavior in Italian adolescents. J Sch Health. 2011;81:393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, Ruan WJ. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:730–736. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamoto J, Schwartz D. Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Soc Dev. 2010;19:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2000. [Accessed; 2016. p. Feb]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barendregt J, Doi SA. MetaXL version 2.1 [computer program] Brisbane: EpiGear International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doi SA, Barendregt JJ, Mozurkewich EL. Meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials: an empirical example. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doi SA, Thalib L. A quality-effects model for meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2008;19:94–100. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c24e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Cancer Research Fund. American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansen DE, Veenstra R, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Reijneveld SA. Early risk factors for being a bully, victim, or bully/victim in late elementary and early secondary education. The longitudinal TRAILS study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:440. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Von Schoon I, Montgomery SM. The relationship between early life experiences and adult depression. Z Psychosom Med Psychoanal. 1997;43:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brunstein Klomek A, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:40–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Wal MF, de Wit CA, Hirasing RA. Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1312–1317. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Due P, Holstein BE, Lynch J, Diderichsen F, Gabhain SN, Scheidt P, Currie C. Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: international comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:128–132. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Due P, Hansen EH, Merlo J, Andersen A, Holstein BE. Is victimization from bullying associated with medicine use among adolescents? A nationally representative cross-sectional survey in Denmark. Pediatrics. 2007;120:110–117. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Björkqvist K. Social defeat as a stressor in humans. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:435–442. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watt MJ, Burke AR, Renner KJ, Forster GL. Adolescent male rats exposed to social defeat exhibit altered anxiety behavior and limbic monoamines as adults. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:564–576. doi: 10.1037/a0015752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koolhaas J, Hermann P, Kemperman C, Bohu sB, Van Den Hoofdakker R, Beersma D. Single social defeat in male rats induces a gradual but long-lasting behavioral change: A model of depression. Neurosci Res Commun. 1990;7:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Lereya ST, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Costello EJ. Childhood bullying involvement predicts low-grade systemic inflammation into adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7570–7575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323641111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Fisher HL, Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:65–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arseneault L, Milne BJ, Taylor A, Adams F, Delgado K, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children’s internalizing problems: a study of twins discordant for victimization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:145–150. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arseneault L, Walsh E, Trzesniewski K, Newcombe R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Bullying victimization uniquely contributes to adjustment problems in young children: a nationally representative cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;118:130–138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]