Abstract

Objective

Impact of a peer navigator program (PNP) develop by a community based participatory research team was examined on African Americans with serious mental illness who were homeless.

Methods

Research participants were randomized to PNP or a treatment-as-usual control group for one year. Data on physical and mental health, recovery, and quality of life were collected at baseline, 4, 8 and 12 months.

Results

Findings from group by trial ANOVAs of omnibus measures of the four constructs showed significant impact over the one year for participants in PNP compared to control described by small to moderate effect sizes. These differences emerged even though both groups showed significant improvements in reduced homelessness and insurance coverage.

Conclusions

Implications for improving in-the-field health care for this population are discussed. Whether these results occurred because navigators were peers per se needs to be examined in future research.

People with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder experience significantly higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared to similar aged individuals.1,2 As a result, they are hospitalized for physical health problems more often3 and die, on average, 15 to 20 years younger than their same aged cohort.4 People with serious mental illnesses are also at greater risk for homelessness which clearly compounds their health problems.1 These problems are even further complicated by ethnicity. Compared to European Americans, twice as many African Americans are below the poverty level5 and three times more likely to experience homelessness.6 Healthcare for people of color is limited by lack of available services or cultural competence. Both mental and primary care services are less available and geographically accessible to African Americans because of poverty.7 People from ethnic minority groups are less insured than the majority culture8 and services that should be provided by the government safety net are lacking.9 These barriers impede African Americans from forming ongoing relationships with primary care providers necessary to promote engagement between patient, family, and provider team, especially for chronic disorders.10

A community-based participatory research11 (CBPR) sought make sense of this problem. A CBPR team comprising eight African Americans with serious mental illness who were homeless, service providers for people who are homeless with mental illness, and investigators conducted qualitative research with 47 key informants (African Americans with serious mental illness who were homeless and related service providers) to better identify causes to poor health in metropolitan Chicago for this group as well as possible solutions.12 Consistent with national surveys6, the 47 participants believed poor health resulted from lower priority on a homeless person’s list of needs (with exposure to the elements and criminal victimization ranked more pressing), lack of available and accessible services, being stigmatized by the health care system, and being disoriented as a result of recurring psychiatric symptoms. One of the solutions identified by the group consistent with people feeling disengaged from the health care system was assistance navigating this system. In particular, focus group respondents reflected on the ideas of patient navigators, paraprofessionals who assist people in traversing a complex health system to meet their individual needs. Respondents said peers would be especially beneficial in this role; individuals with similar lived experiences are perceived as having more empathy for members of the target population and are likely to have street smarts in addressing health needs.

Patient navigators first emerged in cancer clinics, most often being nurses or social workers who walked patients with breast cancer from clinic to lab to therapy during long and stressful treatment periods.13,14 Patient navigators provide both instrumental assistance (offering practical and logistic guidance on doctor’s orders, medications, and therapy options in the real medical setting during real time) and interpersonal support (empathy and reflective listening when components of care became overwhelming).15 Navigators of similar ethnic backgrounds are often viewed as more emotionally present and better listeners leading to being more trusted.16,17 Peers – patients with past experiences with cancer – soon joined the ranks of navigators. Women with past breast cancer acting as navigators to peers led to better engagement in cancer care.18,19,20,17

Services for people with serious mental illness have a rich history of including peer-provided interventions.21 These include treatments delivered by peer providers to address the health needs of participants with serious mental illness. Four randomized clinical trials (RCT) showed people who received versions of psychiatric case management services from peers demonstrated the same level of functional and symptom stability as those provided by professional of paraprofessional staff 22,23,24,25 though these findings have to be interpreted cautiously because they fundamentally represent support of the null hypothesis (i.e., no difference between peer and professional case managers). More recently, people with serious mental illness in hospitals receiving peer mentoring had significantly fewer hospitalizations and inpatient days during the nine months of the study. 26

For the most part, these studies did not examine benefits on health needs per se, though they frequently examined overall improvements in quality of life. Moreover, the peer intervention was not informed by service guidelines that have evolved for patient navigators.14, 27 Hence, the CBPR team conducting the earlier qualitative study12 used study results to adapt navigator guidelines for the needs and priorities of African Americans with serious mental illness who were homeless.28 Here, we report findings from a subsequent RCT comparing the effectiveness of this peer navigator program (PNP) to treatment as usual (TAU). We expected to show people participating in PNP would report improvements in both psychiatric and physical health which would correspond with a better sense of recovery and improved quality of life.

Methods

African Americans with serious mental illness who were homeless were recruited for and randomized to a one-year trial of the PNP compared to treatment-as-usual (TAU). People self-identified as African American and reported being currently homeless according to the definition of the Public Health Service Act: an individual without permanent housing who may live on the streets; stay in a shelter, mission, single room occupancy facilities, abandoned building or vehicle; or in any other unstable or non-permanent situation.29 People also self-reported whether they currently were challenged by mental illness and then provided current diagnosis. Diagnoses included major depression (85.1%), bipolar disorder (22.4%), anxiety disorder (10.4%), PTSD (6.0%) and schizophrenia (9.0%).

To recruit the sample, flyers were posted and widely disseminated in clinics and homeless shelters by CBPR team members. The flyers yielded 97 potential participants who were screened for essential inclusion criteria. Thirty were excluded because they did not report currently having a mental illness, did not meet the definition for current homelessness, or were receiving case management services elsewhere specifically to assist in their physical health goals. After being fully informed to the research protocol and consented, the 67 participants were randomized to condition. All aspects of the protocol were approved by the IRB at the Illinois Institute of Technology and Heartland Alliance. Research participants completed measures at baseline, 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months. They were paid $25/hour plus $10 for travel for each data collection session. Participants were also called weekly to determine all service appointments in the past month. Despite being homeless at entry into the study, all participants had cell phones or access to phones because of a citywide social service effort. Weekly calls helped research assistants develop a relationship and remain in contact with participants between assessment periods. Research participants were paid $5 for completing each call. Of the 67 people consented for the study, seven were lost to follow-up with 2 of these participants dying during the course of the project and 3 being incarcerated.

Peer Navigator Program (PNP)

The PNP was developed by the CBPR team who contrasted PN guidelines from the NCI with findings from our qualitative study as well as CBPR member experiences in mental and physical health care systems. The resulting manual was governed by several basic principles including eight basic values (e.g., accepting, empowering, recovery focused, and available), seven qualities of being part of a team (e.g., networked, accessed, informed, resourced, and supervised), and six fundamental approaches (e.g., proactive, broad focused, active listener, shared decision making, and problem focused).12 These led to four sets of helping skills: (1) basic helper principles; (2) skills to work with the person (such as reflective listening, goal setting, motivational interviewing, strengths interview, and advocacy); (3) skills to respond to a person’s concerns (e.g., interpersonal problem solving, relapse management, harm reduction, cultural competence, and trauma informed care); and (4) role management skills (relationship boundaries, managing burnout, self-disclosure, and street smarts). Peer navigators were also informed about area resources as well as a dynamic service engine locator used by the provider agency. The PNP manual can be downloaded from www.ChicagoHealthDisparities.org for free.

Three peer navigators were fully trained on the program: a full time PNP director and two halftime PNs. All three are African American who were homeless during their adult life and in recovery from serious mental illness. Similar to assertive community treatment (ACT), the team shared responsibilities for all participants assigned to PNP.30 Research assistants (RAs) shadowed peer navigators for one, 6-hour day, each quarter to collect fidelity data.

Treatment-as-usual may have included services provided by the Together for Health system (T4H), a coordinated care entity funded by the state of Illinois’ Medicaid Authority to engage and manage care for individuals with multiple chronic illnesses. T4H was a network of more than 30 mental and/or physical health care programs in Chicago (of which HHO was the lead) to provide integrated care to people with serious mental illness. One of the goals of T4H (and for the PNP, for that matter) was to engage and enroll people with disabilities into its network.

Measures

Research participants completed measures of physical illness, psychiatric disorder, recovery, and quality of life at baseline and again at 4, 8, and 12 months. We started with the TCU Health Form (TCU-HF) as a parsimonious measure of physical and mental health status.31,32 In the past thirty days, research participants were asked the frequency with which they experienced 14 physical health problems (e.g., stomach problems or ulcers, bone joint problems, bladder infections) and 10 mental health problems (e.g., tired for no good reason, nervous, hopeless, depressed) on a five point Likert Scale (5=all the time). Items are averaged to yield a Physical Health and a Mental Health factor. Lower scores represent higher experience of problems with health. Psychometrics are sound and have been reported elsewhere.33,34,32 Findings from the TCU-HF were cross-validated with the 36 items of the SF-36.35,36 The SF-36’s eight, well-validated subfactors represent more the “experience” of physical and mental health and includes subfactors representing physical functioning, role limitations/physical health, role functioning/emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, pain, and general health. The SF-36 has been used, and its psychometrics supported, in more than 4000 studies.37 Higher scores are interpreted as better health experiences.

Recovery was assessed using the five factors of the short form of the Recovery Assessment Scale.38 Research participants complete 24 items – e.g., I’m hopeful about the future. – which they rate on a five point agreement scale (5-strongly agree). Factors include personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, goal orientation and success, reliance on others, and not dominated by symptoms. A recent meta-analysis of 77 articles support its factor structure and psychometrics.39 Higher scores represent better recovery. Quality of life was assessed using Lehman’s 40,41,42 Quality of Life Scale (QLS). Research participants answered six items – e.g., How do you feel about: your life as a whole? – on a 7 point delighted-terrible scale (7=delighted). Research has supported its internal consistency as well as its relationships with recovery and empowerment.43 Higher scores are better quality of life.

Data Analyses

Differences in PNP and TAU groups were assessed to determine whether demographics influenced change in outcome variables and were included as covariates in subsequent analyses where found. Patterns in missing data were assessed with noted adjustments where appropriate. Change in key behaviors related to illness were examined across groups at the four assessment periods: homelessness and insurance. This was done to determine whether change in these behaviors might have influenced outcomes. Homelessness was assessed at each of the four periods and included self-report of current housing. Responses included those coded as homeless (currently living on the streets or in a shelter), in a service-related program (nursing home, group home, support apartment), with family, or in one’s own apartment. Insurance status was also assessed at each time and included yes/no questions representing whether the person received benefits from federal, state, or county programs, and/or private insurers.

Subfactors of the TCU, SF-36, and RAS were averaged to yield an omnibus test of PNP effect. Internal consistencies were determined for total and subscale scores for each of the four assessments. 2×4 ANOVAs (group by trial) were determined for the three total scores plus the single factor of the QLS; effect sizes were reported as η2. Additional 2×4 ANOVAs for subfactors were completed in cases where omnibus analyses were significant.

Results

Missing data were minimal despite this being a sample of people who were homeless with no analyses resulting in excluding data from more than three research participants because they were missing. Hence, we decided not to impute for missing data. Skew, kurtosis, and distribution of dependent variables were examined and seemed satisfactory such that we opted not to transform data. Table 1 summarizes demographics by groups of research participants. Overall, research participants were 38.8% female and 52.9 (SD=8.0) years old on average. The group was 86.6% heterosexual and somewhat varied in education with 64.4% having a high school diploma or less. 13.2% reported some kind of employment. As summarized in the Table, the two groups did not differ significantly on any demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Means or frequencies of demographics across intervention and control groups.

| Group

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Intervention M(SD) or % N= 34 |

Control M(SD) or % N= 33 |

Differences? | |

| Gender | Male | 67.6% | 54.5% | χ2 (1)=1.21, n.s. |

| Female | 32.4% | 45.5% | ||

| Transgender | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | 85.3% | 87.9% | χ2 (2)=.681, n.s. |

| Homosexual | 2.9% | 6.1% | ||

| Bisexual | 11.8% | 6.1% | ||

|

| ||||

| Age | 53.12 (8.09) | 52.64 (8.07) | F(1.65)=0.06, n.s. | |

|

| ||||

| Education | Less than high school | 29.4% | 42.4% | χ2(6)=3.67, n.s. |

| High School Diploma | 32.4% | 24.2% | ||

| Some college | 26.5% | 24.2% | ||

| Associate’s degree | 5.9% | 9.1% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 2.9% | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

| Employed? | Yes | 20.6% | 9.1% | χ2(1)=1.74, n.s. |

| No | 79.4% | 90.9% | ||

Frequency of homelessness and insurance status is summarized in Table 2 for each of the two groups. Homelessness at baseline was not 100% for either group because several research participants reported at the time of assessment temporarily sleeping on family or friends sofas. Both groups decreased the rate of homelessness significantly over the course of the study. As indicated in Table 3, pairwise chi-squared tests show significantly less homelessness (p<.05) from baseline to 8 month and baseline to 12 month assessment for the intervention group and baseline to 4, 8, and 12 month assessment for the control. At 12 months, 91.2% reported domicile for the intervention group and 84.8% for the control group, a nonsignificant difference. Results of a chi-squared test showed the two groups were significantly different in reporting insurance coverage at baseline with the control group reporting greater coverage. At one year, 82.4% of the intervention group and 78.8% of the control group reported insurance coverage, a nonsignificant difference.

Table 2.

Change in homelessness and insurance over the course of the study by group.

| Experience | Groups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Treatment as Usual | |||||||

| B | 4M | 8M | 12M | B | 4M | 8M | 12M | |

| Homeless (% yes) | 76.5%1 | 41.2% | 26.5%2 | 8.8%2 | 72.7%1 | 33.3%2 | 9.1%2 | 15.2%2 |

| Insured (% yes) | 52.9%1 | 67.6% | 79.4%2 | 82.4%2 | 87.9% | 87.9% | 90.9% | 78.8% |

Note. a Criminal arrest at baseline represents life time history. Frequencies with different numerical superscripts differed significantly (p<.05) within intervention or control group.

Table 3.

Group by trial means and standard deviations (M[SD]) of subscale scores for the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS), SF-36, and TCU Health Form (TCU).

| VARIABLE | Range of alphas across the four assessments | GROUP | INTERACTION EFFECT FROM 2×3 ANOVAs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | TAU Control | |||||||||

| baseline | 4 month | 8 month | 12 month | baseline | 4 month | 8 month | 12 month | |||

| SF-36 | ||||||||||

| Physical functioning | .91–.95 | 57.0 [33.2] | 75.4 [23.8] | 72.0 [25.1] | 80.6 [24.7] | 66.5 [27.9] | 67.2 [28.9] | 68.1 [26.3] | 61.5 [27.9] | F(3,51)=9.52, p<.05 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | .83–.85 | 36.6 [41.7] | 45.5 [40.9] | 53.6 [47.0] | 64.3 [41.6] | 44.6 [38.1] | 37.5 [40.5 | 46.4 [40.1] | 44.6 [39.3] | F(3,52)=2.55, p<.10 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | .58–.79 | 33.3 [37.4] | 53.6 [44.8] | 55.9 [45.4] | 78.6 [34.2] | 36.9 [35.5] | 39.3 [40.6] | 55.9 [37.5] | 44.0 [37.5] | F(3,52)=7.17, p<.05 |

| Energy/fatigue | .71–.81 | 43.4 [23.6] | 47.0 [19.2] | 54.3 [23.2] | 58.0 [19.5] | 48.4 [19.2] | 49.3 [23.0] | 47.3 [17.1] | 40.9 [17.2] | F(3,52)=7.71, p<.05 |

| Emotional Well-being | .75–.78 | 53.7 [19.5] | 63.0 [16.6] | 62.0 [20.8] | 71.1 [16.1] | 56.3 [19.9] | 57.8 [20.5] | 59.6 [18.1] | 57.7 [15.7] | F(3,52)= 4.86, p<.05 |

| Social functioning | .48–.74 | 44.6 [24.2] | 64.7 [23.8] | 63.8 [23.4] | 74.1 [20.1] | 52.7 [27.3] | 53.1 [28.8] | 51.8 [21.7] | 58.0 [22.1] | F(3, 52)=4.39, p<.05 |

| Pain | .68–.79 | 47.0 [30.1] | 60.2 [26.2] | 57.0 [24.7] | 68.6 [21.5] | 54.1 [27.2] | 47.5 [28.9] | 50.7 [27.8] | 50.3 [31.0] | F(3,52)=4.72, p<.05 |

| General Health | .68–.71 | 48.4 [20.7] | 55.0 [21.7] | 58.2 [19.0] | 66.6 [20.5] | 51.3 [20.1] | 52.0 [22.1] | 55.5 [20.7] | 50.5 [19.6] | F(3,52)=5.08, p<.05 |

| TCU Health Form | ||||||||||

| Physical health | .67–.74 | 15.9 [6.15] | 13.9 [4.02] | 15.6 [5.72] | 12.6 [2.73] | 17.4 [6.17] | 15.6 [5.30] | 16.0 [4.91] | 16.2 [5.70] | F(3,50)=2.70, p=.05 |

| Psychological distress | .86–.89 | 26.8 [7.61] | 23.0 [8.04] | 22.9 [8.61] | 18.5 [4.79] | 27.4 [8.75] | 25.2 [8.92] | 22.9 [6.87] | 24.4 [7.93] | F(3,51)=3.66, p<.05 |

| Recovery Assessment Scale | ||||||||||

| Personal confidence and hope | .77–.84 | 35.4 [5.8] | 35.9 [4.7] | 37.0 [6.4] | 38.5 [4.7] | 35.7 [5.7] | 37.0 [5.0] | 37.2 [4.8] | 35.1 [5.0] | F(3,51)=5.58, p<.05 |

| Willingness to ask for help | .75–.89 | 11.4 [2.8] | 12.1 [2.6] | 12.2 [3.2] | 13.2 [1.4] | 12.7 [2.2] | 13.1 [1.8] | 13.1 [2.0] | 12.7 [1.9] | F(3,52)=2.93, p<.05 |

| Goal and success orientation | .72–.81 | 20.6 [3.0] | 21.0 [2.0] | 20.9 [3.7] | 22.3 [2.2] | 21.1 [4.2] | 22.0 [2.7] | 21.9 [1.9] | 20.6 [2.9] | F(3,52)=4.96, p<.05 |

| Reliance on others | .62–.79 | 13.9 [2.8] | 15.0 [3.5] | 16.2 [3.0] | 16.1 [2.3] | 14.2 [3.1] | 15.7 [3.0] | 15.1 [2.6] | 14.3 [3.2] | F(3,52)=5.00, p<.05 |

| No domination by symptoms | .51–.72 | 9.6 [2.4] | 10.4 [2.7] | 10.9 [3.1] | 12.4 [1.6] | 9.9 [2.5] | 10.7 [2.1] | 11.0 [1.9] | 9.7 [2.3] | F(3,51)=6.29, p<.05 |

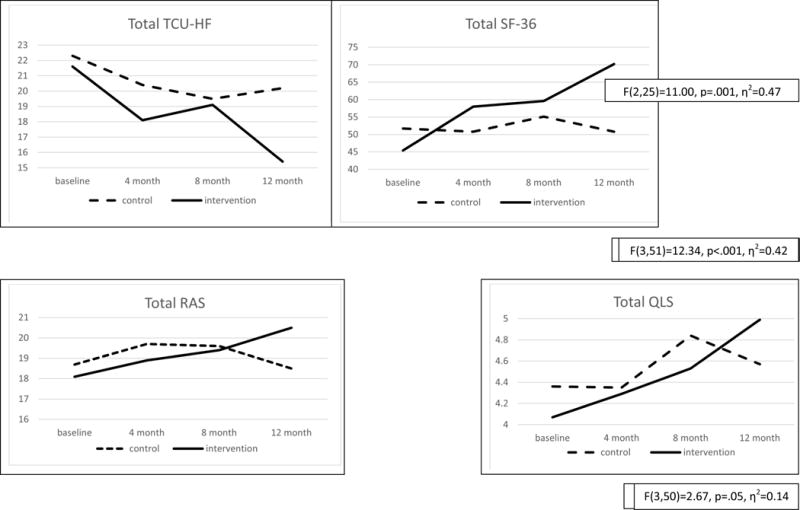

Means of total scores for the TCU-HF, SF-36, RAS, and QLS by group and trial are summarized in Figure 1. Range of internal consistencies were robust for the total scores across the four measurement periods: TCU-HF (.84–.87), SF-36 (.92–.96), RAS (.88–.91), and QLS (.71–.82). Results of the 2×4 ANOVAs for total scores were all significant suggesting those in the PNP showed significant improvements in health compared to the control across the year of assessment. Effect sizes for change in SF-36 and RAS were in the moderate range (.3–.5) and for TCU-HF and QLS were small but not trivial. (.1–.3)44

Figure 1.

Group by trial means of total scores for the TCU Health Form (TCU), SF-36, and Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS), Quality of Life Scale (QLS)

Table 3 summarizes the post-hoc 2×4 ANOVAs for the subfactors of the TCU, SF-36, and RAS. It also provides range of internal consistencies for each subfactor. Seven of the 8 ANOVAs were significant for SF-36 factors with role limitations due to physical health yielding p<.10. All of the 2×4 ANOVAs were significant for TCU-HF and RAS subfactors.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of a peer navigator program (PNP) developed by a CBPR team to address the physical health, mental health, recovery, and quality of life of African Americans with serious mental illness who are homeless. Results showed significant improvement in the self-report indices on the TCU of both physical and mental health for those in the PNP program compared to TAU. Even more, PNP participants showed significant improvement in seven of the eight subscales of the SF-36. Health improvement corresponded with improved recovery as well as quality of life. Effect size of the omnibus analyses were small to moderate.

Both groups improved their domicile and insurance coverage over the course of the study. This suggests peer navigators had positive impact on the health of program participants beyond those that result from improve housing and insurance. Perhaps the instrumental and interpersonal elements of engagement provided by peer navigators in the field were essential to the health gains observed in the study. This conclusion might be tested in future research where the relationship of perceptions of engagement and PNP outcomes are examined.

There are limitations to this study. Results represent a relatively small group of participants and we lost about 10% of participants to follow-up, though these are strong findings for research participants who are homeless at program entry. Still, such a small group prevented additional analyses to determine how the impact of PNP services varied with individual differences. We were, for example, unable to determine whether differences varied by psychiatric diagnosis including whether they interacted with history of substance use disorders. Moreover, diagnoses were self-reported; future research might want to include a structured interview to assess this variable. Future research should also include mediational analyses. In particular, how might PNP influences be mediated by service use?

We hypothesized that navigator services provided by peers would enhance the quality of the intervention. However, this study does not examine peer influences per se. Future research will need to directly compare navigator interventions provided by peers with those offered by paraprofessionals who lack lived experience. Time in the program was one year, which is still somewhat short in the health history of African Americans with serious mental illness who are homeless. One question might be how health gains maintain after PNP, though we suspect peer navigator services, like assertive community treatment models may need to be provided for protracted lengths of time.

Should the various questions listed above be replicated, peer navigators have promise for generally addressing the health care needs of people with serious mental illness, especially those who are most disconnected or disenfranchised from care such as people who are homeless or from minority ethnic groups. Use of peers parallels ever-increasing findings that suggest peer-led services are a valuable resource for the mental health system. Navigation is a different approach than other peer-led services that have been developed and tested for people with mental illness; e.g., psychoeducational programs meant to teach participants medical self-management living skills.45,46 Navigation has more of an ACT feeling, seeking to provide psychoeducational service in the real time and real place of health needs. Future research should directly compare educational versus ACT-like services.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Grant #1R24MD007925

References

- 1.Martens WH. Homelessness and mental disorders: a comparative review of populations in various countries. International Journal of Mental Health. 2001;30:79–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization [Internet] Geneva, Switzerland: p. 2005. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0009/74682/E85482.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mai Q, Holman CDA, Sanfilippo F, et al. The impact of mental illness on potentially preventable hospitalisations: a population-based cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S Census Bureau [Internet] Washington D.C: 2012. Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acsbr12-01.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S Housing and Urban Development [Internet] Washington D.C: 2010. Available from: https://www.onecpd.info/resources/documents/2010HomelessAssessmentReport.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanouette NM, Folsom DP, Sciolla A, et al. Psychotropic medication nonadherence among United States Latinos: a comprehensive review of the literature. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:157–174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, O’Neill A, Park J, et al. Health insurance moderates the association between immigrant length of stay and health status. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2012;14:345–349. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9411-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darnell J. What is the role of free clinics in the safety net? Medical Care. 2011;49:978–84. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182358e6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerant A, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Primary care attributes and mortality: a national person-level study. Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10:34–41. doi: 10.1370/afm.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan P, Pickett S, Kraus D, et al. Community-based Participatory Research Examining the Health Care Needs of African Americans who are Homeless with Mental Illness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2015;26:119–133. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson-White S, Conroy B, Slavish KH, Rosenzweig M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Nursing. 2010;33:127–40. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c40401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Cancer Institute [internet] 2012 Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/crchd/disparities-research/pnrp. Accessed March 13, 2016.

- 15.Parker V, Clark J, Leyson J, et al. Patient navigation: Development of a protocol for describing what navigators do. Health Services Research. 2010;45:514–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han H, Lee HH, Kim MT, et al. Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in nonadherent Korean-American women. Health Education Research. 2009;24:318–329. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen TN, Tran JH, Kagawa-Singer M, et al. A qualitative assessment of community-based breast health navigation services for Southeast Asian women in Southern California: Recommendations for developing a navigator training curriculum. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:87–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan MB, Schumacher A, et al. Breast screening navigator programs within three settings that assist underserved women. Journal of Cancer Education. 2010;25:247–252. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0071-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burhansstipanov L, Wound DB, Capelouto N, et al. Culturally relevant “navigator” patient support. The native sisters. Cancer Practice. 1998;6:191–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giese-Davis J, Bliss-Isberg C, Carson K, et al. The effect of peer counseling on quality of life following diagnosis of breast cancer: An observational study. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:1014–1022. doi: 10.1002/pon.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, et al. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:443–450. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke GN, Herinckx HA, Kinney RF, et al. Psychiatric hospitalizations, arrests, emergency room visits and homelessness of clients with serious and persistent mental illness: Findings from a randomized trial of two ACT programs vs. usual care. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:155–164. doi: 10.1023/a:1010141826867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson L, Shahar G, Stayner DA, et al. Supported socialization for people with psychiatric disabilities: Lessons from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32:453–477. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Donnell M, Parker G, Proberts M, et al. A study of client-focused case management and consumer advocacy: The Community and Consumer Service Project. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:684–693. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon P, Draine J, Delaney M. The working alliance and consumer case management. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1995;22:126–134. doi: 10.1007/BF02518753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sledge WH, Lawless M, Sells D, et al. Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:541–544. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patient Navigator Outreach and Disease Prevention Act of 2005 [internet] 2005 Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collection.action?collectionCode=PLAW. Accessed: March 13, 2016.

- 28.Corrigan PW, Pickett S, Batia K, et al. Peer navigators and integrated care to address ethnic health disparities of people with serious mental illness. Social Work in Public Health. 2014;29:581–93. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2014.893854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Public Health Services Act Section 330 (42 U.S.C 254 b)

- 30.Dixon L. Assertive community treatment: Twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:759–765. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of general psychiatry. 2003;60:184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson D, Joe G, Knight K, et al. Texas Christian University (TCU) short forms for assessing client needs and functioning in addiction treatment. Journal Of Offender Rehabilitation. 2012;51:34–56. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2012.633024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2001;25:494–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baillie A. Predictive gender and education bias in Kessler’s psychological distress scale (K10) Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:743–748. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0935-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware Jr, John E, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hays R, Shapiro M. An Overview of Generic Health Related Quality of Life Measure for HIV Research. Quality of Life Research. 1992;1:91–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00439716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner-Bowker DM, Bartley BJ, Ware JE. Quality Metric Incorporated. Lincoln, RI: 2002. SF-36® Health Survey and “SF” Bibliography: Third Edition (1988–2000) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corrigan PW, Salzer M, Ralph RO, et al. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:1035. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salzer MS, Brusilovskiy E, Prvu-Bettger J, et al. Measuring community participation of adults with psychiatric disabilities: Reliability of two modes of data collection. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2014;59:211. doi: 10.1037/a0036002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehman, Anthony F. The well-being of chronic mental patients: Assessing their quality of life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:369. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790040023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehman Anthony F. The effects of psychiatric symptoms on quality of life assessments among the chronic mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1983;6:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lehman Anthony F. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1988;11:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corrigan PW, Buican B. The construct validity of subjective quality of life in the severely mentally ill. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:281–285. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Druss Benjamin G, Silke A, Compton MT, et al. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldberg Richard W, Dickerson F, Lucksted A, et al. Living Well: an intervention to improve self-management of medical illness for individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2013 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]