Abstract

Gravitational unloading leads to adaptations of the human body, including the spine and its adjacent structures, making it more vulnerable to injury and pain. The Functional Re‐adaptive Exercise Device (FRED) has been developed to activate the deep spinal muscles, lumbar multifidus (LM) and transversus abdominis (TrA), that provide inter‐segmental control and spinal protection. The FRED provides an unstable base of support and combines weight bearing in up‐right posture with side alternating, elliptical leg movements, without any resistance to movement. The present study investigated the activation of LM, TrA, obliquus externus (OE), obliquus internus (OI), abdominis, and erector spinae (ES) during FRED exercise using intramuscular fine‐wire and surface EMG. Nine healthy male volunteers (27 ± 5 years) have been recruited for the study. FRED exercise was compared with treadmill walking. It was confirmed that LM and TrA were continually active during FRED exercise. Compared with walking, FRED exercise resulted in similar mean activation of LM and TrA, less activation of OE, OI, ES, and greater variability of lumbo‐pelvic muscle activation patterns between individual FRED/gait cycles. These data suggest that FRED continuously engages LM and TrA, and therefore, has the potential as a stationary exercise device to train these muscles.

Keywords: Deep spinal muscles, exercise device, fine‐wire electromyography, lumbar spine, rehabilitation

Introduction

Absence of effects of gravity in Low Earth Orbit, reduces the magnitude and frequency of mechanical forces acting on the human body, resulting in profound bone loss in the lower limb and atrophy of some (in particular the so‐called “anti‐gravity”) muscles (Fitts et al. 2001; Chang et al. 2016). Astronauts also experience flattening of the spinal curvatures and lower back pain (LBP) in‐flight (Kerstman et al. 2012) and they are at increased risk of intervertebral disc (IVD) herniation on return to Earth (Johnston et al. 2010).

Long‐term bed‐rest (LTBR) is used as a ground‐based analog of microgravity, and has been found to induce similar changes, including: atrophy of deep spinal muscles, IVD swelling, and a reduced lordotic lumbar spine (Belavy et al. 2011; Hides et al. 2011b). Furthermore, spinal extensor muscle activation becomes more phasic in nature and this persists for at least 6 months following re‐ambulation (Belavy et al. 2007).

But also people with LBP on Earth display atrophy and altered recruitment of the deep spinal muscles (Hodges and Richardson 1996; MacDonald et al. 2009). Two deeply situated spinal muscles that make important contributions to spine control are commonly affected in LBP: the transversus abdominis (TrA) and lumbar multifidus (LM) muscles (Hodges 1999). Both contribute to inter‐segmental control of the spine and pelvis via extensive attachments to vertebrae and pelvic segments (Wilke et al. 1995; Hodges et al. 2003), and are activated in various up‐right movements, often in a manner that is tonic (sustained) and not specific to the direction of internal and external forces (Hodges and Richardson 1997; Moseley et al. 2002). The morphology and function of these muscles are related to spinal integrity and the development of LBP (Hodges and Richardson 1996; Belavy et al. 2011; Hides et al. 2011a), and individuals with LBP display differences in the morphology and behavior similar to those observed after gravitational unloading (i.e. reduced (Ferreira et al. 2004), delayed (Hodges and Richardson 1997; Moseley et al. 2002) and more phasic (Saunders et al. 2004a) activation). Therefore, it is an important aim of the state‐of‐the‐art exercise interventions to prevent or treat LBP to improve motor control of LM and TrA (Hodges et al. 2013c).

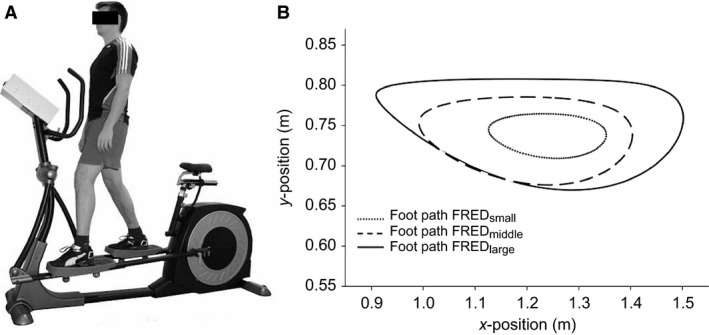

Several exercises (Hodges and Richardson 1996; Hodges 1999; Hides et al. 2011a; Hodges et al. 2013c) are known to activate TrA and LM, and change their recruitment patterns in terms of activation levels, timing, and interplay with other trunk muscles. (Tsao and Hodges 2007, 2008; Tsao et al. 2011; Hodges et al. 2013a). These exercises train activation of these muscles before their integration into function during habitual movements. That means that a currently used strategy to train theses muscles and treat LBP is to first teach patients how to activate them in isolation and then incrementally integrate the newly learned activation patterns into more complex‐, and finally into habitual everyday movements (e.g. reaching over head or standing up from a chair) (Hodges et al. 2013a). However, specific recruitment strategies such as learning how to activate certain trunk muscles in isolation and then to integrate isolated contractions into more complex movements, or how to de‐activate certain trunk muscles where disadvantageous over‐activity is present can be difficult to teach and learn, requiring supervision by a physiotherapist to confirm correct activation (Van et al. 2006; McPherson and Watson 2014). Availability of a simple approach could aid translation to practice. The Functional Re‐adaptive Exercise Device (FRED; Fig. 1) (Debuse et al. 2013; Caplan et al. 2015) was designed on the premise that alternating lower limb movement in an up‐right, weight‐bearing posture, combined with an unstable base of support, would encourage TrA and LM activation. B‐mode ultrasound and surface electromyography (sEMG) studies of FRED exercise provide data indicative of tonic activation of TrA and LM (Caplan et al. 2015), and with less pelvic and spinal motion than over‐ground walking (Gibbon et al. 2013). The device also induces greater activation of trunk extensor muscles and less activation of trunk flexor muscles than walking (Caplan et al. 2015). As these features are opposite to the changes observed following LTBR (Belavy et al. 2011) and microgravity (Hides et al. 2016; Chang et al. 2016) (personal communication, European Space Agency physiotherapist), FRED exercise might be used to help correct changes in trunk muscle activation following prolonged gravitational unloading (Evetts et al. 2014). Moreover, as the device appears to address muscular deficits proposed to play a role in the LBP (Hodges and Richardson 1996; Hides et al. 2011a), FRED exercise could also be useful for these patients.

Figure 1.

The FRED. (A) FRED device in use. (B) Foot paths are shown for the three amplitudes investigated in this study generated using a biomechanical model of the FRED (Lindenroth et al. 2015). The plot shows that the dimensions of the ellipses increase with increasing FRED amplitudes. FRED, Functional Re‐adaptive Exercise Device.

Although estimates of muscle activation with FRED exercise from muscle thickness measures with ultrasound imaging (Debuse et al. 2013) and surface EMG (Caplan et al. 2015) are encouraging, both have limitations (e.g. cross‐talk between muscles for surface EMG; non‐linear relationship between muscle thickness and muscle activation for ultrasound imaging) for interpretation of activation of the deeply situated TrA and LM (Brown and McGill 2008). Considering the limitations of previous studies to investigate the FRED, the present study sought to illuminate the immediate effects more in‐depth using intramuscular fine‐wire EMG. The aims of this investigation were (1) to compare lumbopelvic muscle activation patterns during FRED exercise and treadmill walking, and (2) to assess the effect of different FRED amplitudes (as shown in Fig. 1) on lumbopelvic muscle activation.

Methods

Participants

Nine healthy male volunteers (mean [SD] age: 27 (5) years; height: 1.74 (0.05) m; mass: 72.8 (10.3) kg, body mass index: 24.1 [2.7]) with no history of LBP, or lower limb pain or injury participated in the study. The study was publicly advertised at the University of Queensland, however, only male volunteers responded to the announcement. The fact that only male volunteers could be recruited should not have compromised the findings and generalizability of results given that immediate trunk muscle activation was selected as the main outcome parameter and it is not known to be influenced by gender. Risks and procedures of the study were explained and all participants provided written, informed consent before participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Medical Research Ethics Committee and all procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Instrumentation

Intramuscular electromyography

Before electrode placement, the overlying skin was sterilized (Persist Plus sterilization swab sticks, BD, Franklin Lakes). Intramuscular bipolar fine‐wire electrodes (two Teflon‐coated 75 μm stainless‐steel wires with 1 mm insulation removed from the ends, bent back to form hooks at 2‐ and 3‐mm length, threaded into a hypodermic 0.50 × 70 or 0.50 × 32 mm‐needle) were inserted with B‐mode ultrasound guidance (Aixplorer, Supersonic Imagine, Aix‐en‐Provence, France) into the trunk muscles on the right‐hand side. Electrodes were positioned as follows:

TrA, OI, and OE: Midway between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the ribcage at depths determined by ultrasound imaging;

LM: Between L4/L5, 30 mm laterally to spinous processes until the needle reached the most medial part of the L4 lamina;

ES: At L2, 40 mm lateral to the spinous process.

Surface electromyography

Before electrode placement, the skin was prepared using an abrasive paste (Nuprep, Weaver and Company, Aurora) and cleansed with an alcohol swab. Bipolar surface electrodes (Blue Sensor N, Ambu, Ballerup, Denmark) with an inter‐electrode distance of 22 mm were placed on the skin approximately in parallel with the muscle fibers as follows:

OI/TrAs: medial to the ASIS in a horizontal orientation;

OEs: one electrode on the distal aspect of the 9th rib and one medial to this at an angle of ˜45° from horizontal;

LMs: adjacent to the L5 spinous process at an angle of ˜15° from vertical.

A reference electrode was placed over the iliac crest. EMG signals were pre‐amplified 2000 times, band‐pass filtered between 20 and 1000 Hz (Neurolog, Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK) and recorded at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz using a Power1401 data acquisition system and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK).

Familiarization

Participants were familiarized with exercise on FRED and walking on a motor‐driven treadmill (BH, Vitoria‐Gasteiz, Spain). The 10‐min of familiarization with exercise on FRED included the three amplitude settings (Fig. 1), starting with the smallest. The paths traced by the feet at the three different amplitudes have been reported previously based on a biomechanical model (Lindenroth et al. 2015). Participants were instructed to maintain their feet in contact with the footplates at all times, hold their upper body as still as possible in an up‐right posture and maintain a frequency of 0.42 revolutions per second with a constant angular velocity throughout each complete rotation. Visual feedback of frequency and angular velocity was provided on a screen in front of the participant. For familiarization with treadmill walking, participants initially walked at 0.83 m sec−1 and the speed was increased in 0.056 m sec−1 increments until they reported that they were walking at their estimated “natural” speed. After 5 min of walking at their natural speed, they walked for 5 min at a speed (0.75 m sec−1) and a stride rate of 0.42 Hz (two steps in one stride) that were matched to the FRED settings in its middle amplitude.

Data collection

Participants completed five exercise conditions: FRED exercise at three different amplitudes (FREDsmall, FREDmiddle, FREDlarge), and treadmill walking at their natural speed (Gaitnatural) and that matched to FREDmiddle (Gaitmatched). The order was randomized using a sequence generated by www.randomizer.org. Each exercise condition was performed for 90 sec, with the final 30 sec used for analysis. Between conditions, participants rested for 120 sec in a standardized standing position on the floor. During FRED exercise, a trigger signal was recorded from the internal rotary encoder (RP6010, ifm Electronic GmbH, Essen, Germany) to provide a marker for each completed cycle. For treadmill walking, a footswitch (0.5 inch force sensing resistor, Trossen Robotics) was worn under the heel of the right shoe insole to mark each heel‐strike.

Signal processing

Data were processed off‐line using Matlab (Version 2014a, Mathworks, Natick, MA). For each exercise trial, the trigger signals were used to divide the final 30 sec into individual revolutions or gait cycles. EMG data were visually checked for movement artifacts and any revolutions/gait cycles that included artifacts were removed before further analysis. From a total of 360 recordings, 16 (LMs: 9; OE: 2; OI: 4: OIs: 1) were removed and missing values were replaced using the expectation maximization algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977). EMG data were high‐pass filtered to remove any minor residual artifacts (fine‐wire: 50 Hz; surface: 30 Hz), full‐wave rectified, smoothed using a moving average filter with a time constant of 100 msec, time normalized and averaged across individual cycles.

The processed signals were used to determine mean (EMGmean), peak (EMGpeak), and minimum (EMGmin) amplitudes of the averaged signal (averaged curve of all individual FRED/gait cycles). The time (percentage of each revolution/cycle) for which the muscle was active was calculated. The threshold for activation was defined as an EMG amplitude in excess of five SDs above mean baseline EMG (smallest EMG amplitude for 1 sec). The coefficient of variation between individual revolutions/cycles (Coeffvariation) was calculated. The Coefficient of variation indicates how much the signal during each individual cycle is varying from all other cycles (bounded by 0 and 1; lower Coeffvariation values indicate greater variation between cycles). As the Coeffvariation were high (in particular during FRED exercise), mean, peak, and minimum EMG were also calculated for each separate FRED/gait cycle, before averaging all cycles (Cyclemean; Cyclepeak; Cyclemin, respectively). EMG amplitudes were normalized to the peak activation of the averaged signal (EMGpeak) across all conditions as normalizing to EMGpeak appeared to be more reliable than normalizing to a maximum voluntary contraction (as it was initially planned), where a high inter‐participant variability was observed. Across all trunk muscles, highest EMGpeak values were observed during the gait conditions (typically during the stance phase), and it is thus a robust reference for normalization of amplitudes.

Statistical analyses

After examining each variable for normality a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the five different conditions. When the main effect of Condition was significant (Greenhouse‐Geisser P < 0.05), pairwise post‐hoc comparisons were undertaken using Fisher's least significant difference test (Fisher's LSD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistics software (Version 19, IBM, Armonk, New York). The results (P‐values) of all pairwise comparisons as well as the P‐values for the main effect Condition of the present statistical analysis are listed in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1.

ANOVA and pairwise EMG comparisons of FRED exercise in the middle amplitude and treadmill walking

| Measure | Muscle | Main effect (P) | Post‐hoc (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMGmean | iEMG | TrA | 0.296 | — |

| LM | 0.118 | — | ||

| OI | 0.032 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.02; 0.01 | ||

| OE | 0.006 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.046; 0.019 | ||

| ES | 0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched – 0.027; 0.027 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.01 | FREDmiddle > Gaitnatural–0.045 | |

| OIs | 0.476 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.17 | — | ||

| EMGpeak | iEMG | TrA | 0.107 | — |

| LM | 0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.019; 0.024 | ||

| OI | 0.006 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.008; 0.004 | ||

| OE | 0.02 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.033; 0.018 | ||

| ES | <0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–<0.001; 0.002 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural–0.005 | |

| OIs | 0.056 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.017 | FREDmiddle < Gaitmatched–0.05 | ||

| EMGmin | iEMG | TrA | 0.012 | — |

| LM | 0.023 | FREDmiddle > Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.028; 0.038 | ||

| OI | 0.3 | — | ||

| OE | 0.55 | — | ||

| ES | 0.2 | — | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.001 | FREDmiddle > Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.004; 0.006 | |

| OIs | 0.34 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.26 | — | ||

| Cyclemean | iEMG | TrA | 0.18 | — |

| LM | 0.23 | — | ||

| OI | 0.083 | — | ||

| OE | 0.006 | FREDmiddle < Gaitmatched–0.024 | ||

| ES | 0.003 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.037; 0.048 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.05 | — | |

| OIs | 0.4 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.15 | — | ||

| Cyclepeak | iEMG | TrA | 0.065 | — |

| LM | 0.007 | — | ||

| OI | 0.065 | — | ||

| OE | 0.002 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.014; 0.003 | ||

| ES | <0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–<0.001; 0.001 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.003 | — | |

| OIs | 0.115 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.032 | — | ||

| Cyclemin | iEMG | TrA | 0.044 | — |

| LM | 0.29 | — | ||

| OI | 0.7 | — | ||

| OE | 0.19 | — | ||

| ES | 0.26 | — | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.003 | FREDmiddle > Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–<0.005; 0.006 | |

| OIs | 0.67 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.62 | — | ||

| Coeffvariation | iEMG | TrA | 0.023 | — |

| LM | <0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–<0.001; <0.001 | ||

| OI | 0.007 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural–0.041 | ||

| OE | 0.003 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–<0.001; 0.004 | ||

| ES | <0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched –<0.001; 0.002 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | <0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched –<0.001; 0.003 | |

| OIs | 0.007 | — | ||

| OEs | <0.001 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural; Gaitmatched–0.009; 0.004 | ||

| Time active | iEMG | TrA | 0.3 | — |

| LM | 0.1 | — | ||

| OI | 0.15 | — | ||

| OE | 0.031 | FREDmiddle < Gaitnatural–0.024 | ||

| ES | 0.08 | — | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.2 | — | |

| OIs | 0.35 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.62 | — | ||

Post‐hoc analyses were performed provided the P‐value for main effect (condition) was ≤ 0.05 while for pairwise comparisons only P ≤ 0.05 are presented.

IEMG, intramuscular EMG; sEMG, surface EMG.

Table 2.

ANOVA and Pairwise EMG comparisons of FRED exercise in the three different amplitude settings

| Measure | Muscle | Main effect (P) | Post‐hoc (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMGmean | iEMG | TrA | 0.296 | — |

| LM | 0.118 | — | ||

| OI | 0.032 | FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.012 | ||

| OE | 0.006 | FREDsmall < FREDlarge–0.037 | ||

| ES | 0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge; FREDmiddle<FREDlarge–0.024; 0.005; 0.034 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.01 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.005; 0.018 | |

| OIs | 0.476 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.17 | — | ||

| EMGpeak | iEMG | TrA | 0.107 | — |

| LM | 0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.008; 0.006 | ||

| OI | 0.006 | FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.033 | ||

| OE | 0.02 | FREDsmall; FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.012; 0.012 | ||

| ES | <0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.009; 0.006 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge; FREDmiddle <FREDlarge –0.005; <0.001; 0.008 | |

| OIs | 0.056 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.017 | FREDsmall < FREDlarge–0.002 | ||

| EMGmin | iEMG | TrA | 0.012 | — |

| LM | 0.023 | — | ||

| OI | 0.3 | — | ||

| OE | 0.55 | — | ||

| ES | 0.2 | — | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle –0.005 | |

| OIs | 0.34 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.26 | — | ||

| Cyclemean | iEMG | TrA | 0.18 | — |

| LM | 0.23 | — | ||

| OI | 0.083 | — | ||

| OE | 0.006 | FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.038 | ||

| ES | 0.003 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.025; 0.011 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.05 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.006; 0.017 | |

| OIs | 0.4 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.15 | — | ||

| Cyclepeak | iEMG | TrA | 0.065 | — |

| LM | 0.007 | FREDsmall <FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.008; 0.01 | ||

| OI | 0.065 | — | ||

| OE | 0.002 | FREDsmall; FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.018; 0.023 | ||

| ES | <0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge; FREDmiddle < FREDlarge – 0.012; 0.001; 0.038 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.003 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge; FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.002; <0.001; 0.011 | |

| OIs | 0.115 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.032 | FREDsmall < FREDlarge –0.003 | ||

| Cyclemin | iEMG | TrA | 0.044 | — |

| LM | 0.29 | — | ||

| OI | 0.7 | — | ||

| OE | 0.19 | — | ||

| ES | 0.26 | — | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.003 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.001; 0.037 | |

| OIs | 0.67 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.62 | — | ||

| Coeffvariation | iEMG | TrA | 0.023 | FREDsmall < FREDlarge –0.025 |

| LM | <0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge–0.033; 0.006 | ||

| OI | 0.007 | — | ||

| OE | 0.003 | — | ||

| ES | <0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge–0.036; 0.009 | ||

| sEMG | LMs | <0.001 | FREDsmall; FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.01; 0.046 | |

| OIs | 0.007 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge–0.031; 0.029 | ||

| OEs | <0.001 | FREDsmall < FREDmiddle; FREDlarge –0.015; 0.001 | ||

| Time active | iEMG | TrA | 0.3 | — |

| LM | 0.1 | — | ||

| OI | 0.15 | — | ||

| OE | 0.031 | FREDmiddle < FREDlarge–0.025 | ||

| ES | 0.08 | — | ||

| sEMG | LMs | 0.2 | — | |

| OIs | 0.35 | — | ||

| OEs | 0.62 | — | ||

Post‐hoc analyses were performed provided the P ‐value for main effect (condition) was ≤ 0.05 while for pairwise comparisons only P ≤ 0.05 are presented.

Results

All participants completed the entire data collection with no adverse events.

General features of EMG during FRED exercise and treadmill walking

Figure 2 depicts typical EMG recordings from one participant from the FREDmiddle and the two treadmill conditions. Visual inspection of the signals reveals a high variability between individual cycles for FREDmiddle.. This contrasts a more consistent pattern observed during treadmill walking. With treadmill walking, LM (LMs) and ES demonstrate typical phasic activation with bursts of activity aligned to heel‐strike, whereas activation during FREDmiddle appears more random and not consistently aligned with any specific cycle event.

Figure 2.

Representative processed EMG curves of one participant. Intramuscular and surface EMG recordings from one participant for FRED middle and the two gait conditions. The thick black line depicts the averaged signal of all individual cycles (thin gray lines) as calculated analyzing the last 30 sec of each task. The light dotted line at the bottom of each plot indicates the zero reference for each channel. Cycle length represents one complete revolution on the FRED or the time from heel contact to heel contact of the right foot for treadmill walking. Note that unlike the gait data that begin and end with right foot strike, data for the FRED exercise are temporally organized to a set point in the smooth foot path.

Aim 1: Comparison between FRED exercise and treadmill walking

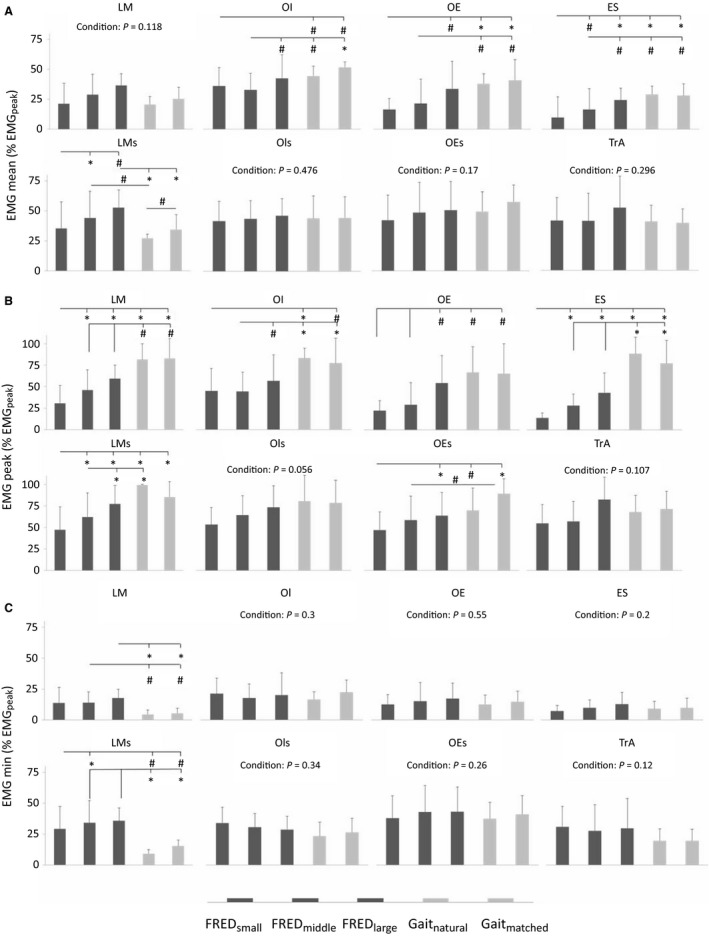

When data were averaged across consecutive cycles before analysis, recordings with fine‐wire electrodes revealed that EMGmean, EMGpeak, and EMGmin for TrA showed no difference between FREDmiddle and treadmill walking (Table 1, Fig. 3). LM EMGmean was also not different when comparison was made between FREDmiddle and walking, but LM EMGpeak was lower and EMGmin was observed higher during FREDmiddle than walking, and these latter observations imply less fluctuation of activation (i.e. more “tonic”). Fine‐wire recordings of the superficial muscles OI, OE, and ES showed lower EMGmean and EMGpeak during FREDmiddle than both treadmill tasks (Table 1, Fig. 3), but EMGmin was not significantly different.

Figure 3.

Mean, peak and min EMG amplitudes of the averaged EMG data. Group mean (SD) of intramuscular and surface EMG signals during the three FRED conditions (FRED small, FRED middle, FRED large) and treadmill walking at natural speed (Gaitnatural) and at a step frequency (0.84 Hz) matched to FRED middle (Gaitmatched). The figure shows mean (A), peak (B) and minimum (C) amplitude of the averaged curves normalized to the greatest peak activation of the averaged signal for each muscle. Intramuscular EMG–LM, lumbar multifidus; OI, obliquus internus abdominis; OE, obliquus externus abdominis; ES, erector spinae; TrA, transversus abdominis; surface EMG‐LMs, lumbar multifidus; OIs, obliquus internus abdominis; OEs, obliquus externus abdominis. *P < 0.01 and # P < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

Analysis of the data separately for each repetition, revealed similar observations to the analysis of the averaged EMG (Fig. 4). TrA and OI Cyclemean, Cyclepeak, and Cyclemin did not differ between FREDmiddle and treadmill walking. Although LM Cyclemean and Cyclemin did not differ between FREDmiddle and walking, LM Cyclepeak was lower in FREDmiddle than both walking conditions. OE Cyclemean was lower during FREDmiddle than Gaitmatched, OE Cyclepeak was less during FREDmiddle than both walking tasks. OE Cyclemin did not differ between FREDmiddle and the walking conditions. ES Cyclemean and Cyclepeak during FREDmiddle were lower than during both walking tasks, but ES Cyclemin did not differ between conditions.

Figure 4.

Mean, peak and min amplitudes determined from individual FRED/gait cycles. (A) Mean, (B) peak, and (C) minimum EMG recorded from all recorded intramuscular and surface EMG signals from individual FRED/gait cycles. EMG amplitudes were normalizd to the greatest peak activation of the averaged signal for each muscle. Intramuscular EMG–LM, lumbar multifidus; OI, obliquus internus abdominis; OE, obliquus externus abdominis; ES, erector spinae; TrA, transversus abdominis; surface EMG‐LMs, lumbar multifidus; OIs, obliquus internus abdominis; OEs, obliquus externus abdominis. *P < 0.01 and # P < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

The duration of activation (percentage of FRED/gait cycle) showed that OE was active for less time during FREDmiddle than Gaitnatural. There were no difference for the other muscles.

The coefficient of variation between consecutive movement cycles was lower (i.e. more variable) for LM, OE, and ES during FREDmiddle than both walking tasks, and OI Coeffvariation was lower during FREDmiddle than Gaitnatural only (Table 1, Fig. 5). The TrA Coeffvariation did not differ between FREDmiddle and treadmill walking.

Figure 5.

Coefficient of variation and time active. (A) The coefficient of variation indicates the variation of individual FRED/gait cycles from the averaged signal. (B) Time active indicates the percentage of time a muscle was active during the task. Intramuscular EMG–LM, lumbar multifidus; OI, obliquus internus abdominis; OE, obliquus externus abdominis; ES, erector spinae; TrA, transversus abdominis; surface EMG‐LMs, lumbar multifidus; OIs, obliquus internus abdominis; OEs, obliquus externus abdominis. *P < 0.01 and # P < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

Aim 2: Comparison between FRED exercise amplitudes

FRED exercise amplitude affected some aspects of trunk muscles activity. Although EMGmean of LM and TrA were unaffected through amplitude changes of FRED, OE EMGmean increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDlarge, and ES EMGmean increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDmiddle, and from FREDmiddle to FREDlarge. OI EMGmean increased significantly from FREDmiddle to FREDlarge.

TrA EMGpeak and EMGmin were not significantly different among the FRED conditions. LM EMGpeak increased from FREDsmall to FREDlarge, whereas EMGmin of LM, OI, OE, ES were not different between conditions. OI EMGpeak was higher for FREDlarge than FREDmiddle. OE EMGpeak increased significantly from FREDsmall and FREDmiddle to FREDlarge, and ES EMGpeak increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDmiddle and FREDlarge.

Surface EMG recordings showed that LMs EMGmean increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDmiddle and from FREDmiddle to FREDlarge, whereas OIs and OEs EMGmean remained unaffected. LMs EMGmin increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDmiddle, whereas OIs and OEs EMGmin did not change. LMs EMGpeak increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDmiddle and from FREDmiddle to FREDlarge, OEs EMGpeak increased significantly from FREDsmall to FREDlarge, whereas OIs EMGpeak remained unaffected (Table 2, Fig. 3). The duration of activation (percentage of FRED/gait cycle) did not differ between conditions for any muscle except OE, which was active for a longer period during FREDlarge than FREDmiddle (Table 2, Fig. 5).

Analysis of the data separately for each cycle were similar to the findings of the averaged data. Some minor differences were observed for OI, ES, and LMs (Table 2, Figs. 3, 4). Between‐cycle variation was affected by FRED amplitude. For intramuscular EMG recordings, LM, and ES Coeffvariation were lower for FREDsmall than for FREDmiddle and FREDlarge, and TrA Coeffvariation was lower for FREDsmall than for FREDlarge only (Fig. 5, Panel a). For surface EMG recordings, LMs Coeffvariation for FREDsmall and FREDmiddle exercise was lower than for FREDlarge, whereas OIs and OEs Coeffvariation were lower for FREDsmall than for FREDmiddle and FREDlarge (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study presents novel results about the immediate effects of FRED exercise on lumbo‐pelvic muscle recruitment and adds important knowledge to the investigation process of a device that claims to be helpful in the recovery of LBP and in the rehabilitation phase after gravitational unloading (i.e. space flight, bed rest). Consistent with the proposed objective of FRED exercise, these results provide evidence that TrA and LM are activated continuously throughout cycles on the device. FRED exercise differed from treadmill in several respects, including more “tonic” pattern of activation of LM and lower activation of several superficial trunk muscles. These data highlight that FRED exercise may have therapeutic benefits for LBP patients and for individuals after prolonged gravitational unloading.

Trunk muscle activity difference between FRED exercise and treadmill walking

Selective EMG recordings of trunk muscles with fine‐wire intramuscular electrodes during FRED exercise and treadmill walking revealed differences between these tasks, with some similarities and differences to previous non‐invasive recordings (Caplan et al. 2015). Previous studies of acute exercise with FRED reported the activation (surface EMG) of deep spinal muscles, greater trunk extensor muscle activation, less trunk flexor muscle activation, and a phasic‐to‐tonic shift of LM activation when compared with walking (Debuse et al. 2013; Caplan et al. 2015). Using selective fine‐wire recordings, the present data confirm sustained activation of LM and TrA during FRED exercise. Although no difference observed in the mean activation between FRED exercise and treadmill walking, consistent with the phasic‐to‐tonic shift in LM reported by Caplan et al. (2015), the pattern of intramuscular LM EMG during FRED exercise was characterized by less fluctuating continuous activation (greater minimum activation, lesser peak activation). This was observed for both surface and fine‐wire LM recordings in the present study.

The observation of less variation in LM EMG amplitude (lower peaks, greater minima) during FRED exercise than walking is likely to be explained by the absence of ground impacts at foot contact in FRED, which are known to lead to high peaks of LM activation in walking (Saunders et al. 2004b). It follows that there would be less difference in the pattern of TrA between FRED and walking as activation of that muscle is less dominated by peaks at foot contact in walking (Saunders et al. 2004b).

FRED exercise also aims to reduce the activation of more superficial trunk muscles that tend to have enhanced activation in the LBP (Hodges et al. 2013b). As reported from the surface EMG recordings (Caplan et al. 2015), mean trunk flexor (OI and OE) muscles activation was less in FRED exercise than over‐ground walking. In the present study, we also observed shorter duration of OE EMG bursts during FRED. Comparison of surface and fine‐wire recordings indicated that differences between tasks were more readily observed with selective fine‐wire electrodes, as surface recordings failed to show differences in some parameters. A departure from the observations of Caplan et al. (2015) is that trunk extensor activation (ES EMG) was less, rather than more during FRED. This difference is best explained by EMG cross‐talk, whereby each EMG recording site reflects the activation of multiple muscles within the recording field. Greater recording zone size for surface electrodes means those recordings will be more compromised by adjacent muscle activity. For ES, the previously used surface electrodes (Caplan et al. 2015) may have reflected activation of the superficially placed latissimus dorsi or thoroacolumbar erector spinae muscles, which we did not record. Similar to the argument presented for LM above, the lower mean and peak activation of the superficial muscles (OI, OE, and ES) during FRED is likely to be explained by removal of the high demand for trunk control related to foot strike.

A new observation was that activation of all trunk muscles was more variable between cycles (i.e. lower coefficient of variation) during FRED exercise. This contrasts the highly regular pattern of phasic modulation of activation of most muscles at consistent time points of each cycle in treadmill walking. There are several possible explanations. First, greater between‐cycle variation might reflect the novelty of this exercise, and participants' lack of familiarity. Analysis of habitual activities shows that motor units tend to fire more synchronously and more predictably when a movement is repeatedly performed (Enoka 1997). When quantified with the coefficient of variation (amount of variation of individual cycles from the mean of all cycles), a high value was observed for all trunk muscles during the walking trials. This is consistent with the highly familiar and repeatable nature of the task and associated muscle activity. Gait is a habitual movement for healthy humans that is at least in part controlled by spinal cord neural circuits (Bussel et al. 1996), and its interplay of muscle activation is genetically determined (Andersson et al. 2012) with fine‐tuning over decades of exposure.

Second, as mentioned above, FRED exercise lacks high ground reaction forces at foot strike. As activation of many of the trunk muscles is associated with foot strike (Saunders et al. 2004b) this would tend to constrain the variation between cycles, leading to a higher coefficient of variation.

Third, greater variation may reflect greater cycle‐to‐cycle variation in task demands. FRED exercise was designed to continuously challenge the muscles controlling lumbo‐pelvic posture and alignment. By making the base of support less stable, the intention was to enforce a need for the trunk muscles to continuously adjust the spine and pelvis position. This challenge is likely to vary between cycles, providing a potential explanation for less consistent EMG patterns. In the present study, the lowest correlation coefficient for all trunk muscles was observed during FRED exercise with the small or middle amplitude, indicating that the challenge may be greater (i.e. more unstable) in these situations.

Changes in trunk muscle activation with FRED exercise amplitudes

Trunk muscle activation changed significantly when the foot‐path lengths during FRED exercise were altered through changes in the movement amplitudes. For most trunk muscles (LM, OI, OE/OEs, and ES) the greatest EMGpeak, EMGmean, and/or EMGmin activities were recorded during FRED exercise with the large amplitude, although the specific parameters differed between muscles. Two features of FRED exercise explain the increase with FRED amplitude. First, the large amplitude setting imposes greater excursion of the hips, placing greater demand for the control of proximal body segments. Second, the instability of the base of support is likely to be more difficult to control with large amplitudes. This will induce greater challenge for control, particularly for the participants in this study who were novice users (limited to 10 min of familiarization). During the large amplitude exercise it was not uncommon to observe “jerky” movements and associated peaks in trunk muscle activation. Lower cycle‐to‐cycle variation of LM/LMs, TrA, OI/OIs), ES and OEs with longer footpaths could imply that although this task is more challenging, the points in the task that were most challenging may be more consistent between repetitions which may tend to constrain the periods of most activity between repetitions.

Potential role of FRED in rehabilitation of astronauts, individuals with LBP and following LTBR

Present results confirm that FRED exercise induces tonic activation of deeper trunk muscles, with lower mean activation of superficial spinal muscles (ES, OI, and OE) than treadmill walking at similar conditions. These features highlight the potential role of FRED exercise to counteract impaired (delayed and phasic) activation of deep lumbo‐pelvic muscles (Hodges and Richardson 1996; Ferreira et al. 2004; Saunders et al. 2004a; Hodges et al. 2013b) and increased activation of more superficial trunk muscles (van Dieen et al. 2003) observed in the LBP, as well as after LTBR (Belavy et al. 2007) and in the decreased size of deep spinal muscles as reported from astronauts after their missions (Hides et al. 2016; Chang et al. 2016).

Repeated exposure to postural perturbations can improve timing and amplitude of postural muscle activation (Horak and Nashner 1986). Further, repeated postural challenges in a specific environment developed new motor control strategies, which were transferrable to another environment (Horak and Nashner 1986). Taken together with our observed changes in muscle activation with FRED exercise, this implies FRED exercise could aid reversal of compromised neuromotor control and that the neuromotor control of trunk muscles trained through FRED exercise might be transferrable to other tasks. Clinical trials are needed to confirm the ability of FRED exercise to alter trunk muscle neuromotor control in the long term in individuals with deficits in trunk muscle function.

Limitations

This study focused on a limited set of muscles based on the extensive literature highlighting compromised (LM and TrA) and augmented (OE, OI, and ES) activation in the LBP and after bed rest. However, this represents a subset of the trunk muscles that control the spine. Recent work highlights high variation between individuals (Hodges et al. 2013b) and involvement of additional muscles (e.g. psoas, quadratus lumborum) (Park et al. 2013). The present study shows differences (particularly for OI and OE) between surface and intramuscular recordings, which highlights that surface electrodes do not accurately represent their activation and highlights that fine‐wire electrodes are necessary to study the complex muscle system of the trunk.

Our interest in this study was to investigate individuals with no previous experience with FRED and a standardized period of familiarization (10 min) before data collection. It is unknown whether muscle activation patterns would differ with greater familiarity with FRED exercise, particularly when using the larger amplitudes.

Conclusion

Intramuscular EMG recordings confirm that FRED exercise activates LM and TrA continuously. Moreover, compared with walking, trunk muscle activation during FRED exercise is associated with less activity of superficial muscles while the deep spinal muscles show similar mean activities. The patterns of activation during individual FRED cycles vary more than during walking. These data support the notion that FRED exercise might be effective to train the deep spinal muscles for populations where spinal muscle atrophy and compromised neuromotor control might be present (LBP, recovery after LTBR and space flight). Future studies are planned to investigate whether FRED exercise induces long‐term improvement in functional and morphological parameters of trunk muscles.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

Dr Simon Evetts receives special thanks for establishing the initial cooperation between the European Space Agency and Northumbria University. Paul Hodges receives a senior principal research fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Markus Kiel from the University of Queensland and of courses all participants.

Weber T., Debuse D., Salomoni S. E., Elgueta Cancino E. L., De Martino E., Caplan N., Damann V., Scott J., Hodges P. W.. Trunk muscle activation during movement with a new exercise device for lumbo‐pelvic reconditioning, Physiol Rep, 5 (6), 2017, e13188, doi: 10.14814/phy2.13188

Funding Information

This investigation was funded by the European Space Agency.

References

- Andersson, L. S. , Larhammar M., Memic F., Wootz H., Schwochow D., Rubin C. J., et al. 2012. Mutations in DMRT3 affect locomotion in horses and spinal circuit function in mice. Nature 488:642–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belavy, D. L. , Richardson C. A., Wilson S. J., Felsenberg D., and Rittweger J.. 2007. Tonic‐to‐phasic shift of lumbo‐pelvic muscle activity during 8 weeks of bed rest and 6‐months follow up. J. Appl. Physiol. 103:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belavy, D. L. , Armbrecht G., Richardson C. A., Felsenberg D., and Hides J. A.. 2011. Muscle atrophy and changes in spinal morphology: is the lumbar spine vulnerable after prolonged bed‐rest? Spine 36:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. H. , and McGill S. M.. 2008. An ultrasound investigation into the morphology of the human abdominal wall uncovers complex deformation patterns during contraction. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 104:1021–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussel, B. , Roby‐Brami A., Neris O. R., and Yakovleff A.. 1996. Evidence for a spinal stepping generator in man. Paraplegia 34:91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, N. , Gibbon K., Hibbs A., Evetts S., and Debuse D.. 2015. Phasic‐to‐tonic shift in trunk muscle activity relative to walking during low‐impact weight bearing exercise. Acta Astronaut. 104:388–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, D. G. , Healey R. M., Snyder A. J., Sayson J. V., Macias B. R., Coughlin D. G., et al. 2016. Lumbar spine paraspinal muscle and intervertebral disc height changes in astronauts after long‐duration spaceflight on the international space station. Spine 15:1917–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debuse, D. , Birch O., St Clair Gibson A., and Caplan N.. 2013. Low impact weight‐bearing exercise in an upright posture increases the activation of two key local muscles of the lumbo‐pelvic region. Physiother. Theory Pract. 29:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster, A. P. , Laird N. M., and Rubin D. B.. 1977. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- van Dieen, J. H. , Selen L. P., and Cholewicki J.. 2003. Trunk muscle activation in low‐back pain patients, an analysis of the literature. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 13:333–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoka, R. M. 1997. Neural adaptations with chronic physical activity. J. Biomech. 30:447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evetts, S. N. , Caplan N., Debuse D., Lambrecht G., Damann V., Petersen N., et al. 2014. Post space mission lumbo‐pelvic neuromuscular reconditioning: a european perspective. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 85:764–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P. H. , Ferreira M. L., and Hodges P. W.. 2004. Changes in recruitment of the abdominal muscles in people with low back pain: ultrasound measurement of muscle activity. Spine 29:2560–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts, R. H. , Riley D. R., and Widrick J. J.. 2001. Functional and structural adaptations of skeletal muscle to microgravity. J. Exp. Biol. 204:3201–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon, K. C. , Debuse D., and Caplan N.. 2013. Low impact weight‐bearing exercise in an upright posture achieves greater lumbopelvic stability than overground walking. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 17:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hides, J. , Stanton W., Mendis M. D., and Sexton M.. 2011a. The relationship of transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus clinical muscle tests in patients with chronic low back pain. Man. Ther. 16:573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hides, J. A. , Lambrecht G., Richardson C. A., Stanton W. R., Armbrecht G., Pruett C., et al. 2011b. The effects of rehabilitation on the muscles of the trunk following prolonged bed rest. Eur. Spine J. 20:808–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hides, J. , Lambrecht G., Stanton W., and Damann V.. 2016. Changes in multifidus and abdominal muscle size in response to microgravity: possible implications for low back pain research. Eur. Spine J. 25(Suppl. 1): 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. W. 1999. Is there a role for transversus abdominis in lumbo‐pelvic stability? Man. Ther. 4:74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. W. , and Richardson C. A.. 1996. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain. A motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine 21:2640–2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. W. , and Richardson C. A.. 1997. Feedforward contraction of transversus abdominis is not influenced by the direction of arm movement. Exp. Brain Res. 114:362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. , Kaigle Holm A., Holm S., Ekstrom L., Cresswell A., Hansson T., et al. 2003. Intervertebral stiffness of the spine is increased by evoked contraction of transversus abdominis and the diaphragm: in vivo porcine studies. Spine 28:2594–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. W. , Cholewicki J., and Van Dieen J. H.. 2013a. Spinal control: the rehabilitation of back pain: state of the art and science. Elsevier Health Sciences, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. W. , Coppieters M. W., MacDonald D., and Cholewicki J.. 2013b. New insight into motor adaptation to pain revealed by a combination of modelling and empirical approaches. Eur. J. Pain 17:1138–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, P. W. , van Dillen L. R., McGill S., Brumagne S., Hides J. A., and Moseley G. L.. 2013c. Integrated clinical approach to motor control interventions in low back and pelvic pain Pp. 243‐309 in Hodges P., Cholewicki J. and van Dieen J. H., eds. Spinal control: The rehabilitation of back pain. Churchill Livingstone, London. [Google Scholar]

- Horak, F. B. , and Nashner L. M.. 1986. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support‐surface configurations. J. Neurophysiol. 55:1369–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, S. L. , Campbell M. R., Scheuring R., and Feiveson A. H.. 2010. Risk of herniated nucleus pulposus among U.S. astronauts. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 81:566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstman, E. L. , Scheuring R. A., Barnes M. G., DeKorse T. B., and Saile L. G.. 2012. Space adaptation back pain: a retrospective study. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 83:2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenroth, L. , Caplan N., Debuse D., Salomoni S. E., Evetts S., and Weber T.. 2015. A novel approach to activate deep spinal muscles in space—Results of a biomechanical model. Acta Astronaut. 116:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, D. , Moseley G. L., and Hodges P. W.. 2009. Why do some patients keep hurting their back? Evidence of ongoing back muscle dysfunction during remission from recurrent back pain. Pain 142:183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, S. L. , and Watson T.. 2014. Training of transversus abdominis activation in the supine position with ultrasound biofeedback translated to increased transversus abdominis activation during upright loaded functional tasks. PM R 6:612–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, G. L. , Hodges P. W., and Gandevia S. C.. 2002. Deep and superficial fibers of the lumbar multifidus muscle are differentially active during voluntary arm movements. Spine 27:E29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, R. J. , Tsao H., Cresswell A. G., and Hodges P. W.. 2013. Changes in direction‐specific activity of psoas major and quadratus lumborum in people with recurring back pain differ between muscle regions and patient groups. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 23:734–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, S. , Coppieters M., and Hodges P.. 2004a. Reduced tonic activity of the deep trunk muscle during locomotion in people with low back pain in Hodges P., ed. World Congress of Low Back Pain and Pelvic Pain, November 10–13, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, S. W. , Rath D., and Hodges P. W.. 2004b. Postural and respiratory activation of the trunk muscles changes with mode and speed of locomotion. Gait Posture. 20:280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, H. , and Hodges P. W.. 2007. Immediate changes in feedforward postural adjustments following voluntary motor training. Exp. Brain Res. 181:537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, H. , and Hodges P. W.. 2008. Persistence of improvements in postural strategies following motor control training in people with recurrent low back pain. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 18:559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, H. , Danneels L. A., and Hodges P. W.. 2011. ISSLS prize winner: smudging the motor brain in young adults with recurrent low back pain. Spine 36:1721–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van, K. , Hides J. A., and Richardson C. A.. 2006. The use of real‐time ultrasound imaging for biofeedback of lumbar multifidus muscle contraction in healthy subjects. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 36:920–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, H. J. , Wolf S., Claes L. E., Arand M., and Wiesend A.. 1995. Stability increase of the lumbar spine with different muscle groups. A biomechanical in vitro study. Spine 20:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]