Abstract

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are crucial components of fertile soils, able to provide several ecosystem services for crop production. Current economic, social and legislative contexts should drive the so-called “second green revolution” by better exploiting these beneficial microorganisms. Many challenges still need to be overcome to better understand the mycorrhizal symbiosis, among which (i) the biotrophic nature of AMF, constraining their production, while (ii) phosphate acts as a limiting factor for the optimal mycorrhizal inoculum application and effectiveness. Organism fitness and adaptation to the changing environment can be driven by the modulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain, strongly connected to the phosphorus processing. Nevertheless, the role of the respiratory function in mycorrhiza remains largely unexplored. We hypothesized that the two mitochondrial respiratory chain components, alternative oxidase (AOX) and cytochrome oxidase (COX), are involved in specific mycorrhizal behavior. For this, a complex approach was developed. At the pre-symbiotic phase (axenic conditions), we studied phenotypic responses of Rhizoglomus irregulare spores with two AOX and COX inhibitors [respectively, salicylhydroxamic acid (SHAM) and potassium cyanide (KCN)] and two growth regulators (abscisic acid – ABA and gibberellic acid – Ga3). At the symbiotic phase, we analyzed phenotypic and transcriptomic (genes involved in respiration, transport, and fermentation) responses in Solanum tuberosum/Rhizoglomus irregulare biosystem (glasshouse conditions): we monitored the effects driven by ABA, and explored the modulations induced by SHAM and KCN under five phosphorus concentrations. KCN and SHAM inhibited in vitro spore germination while ABA and Ga3 induced differential spore germination and hyphal patterns. ABA promoted mycorrhizal colonization, strong arbuscule intensity and positive mycorrhizal growth dependency (MGD). In ABA treated plants, R. irregulare induced down-regulation of StAOX gene isoforms and up-regulation of genes involved in plant COX pathway. In all phosphorus (P) concentrations, blocking AOX or COX induced opposite mycorrhizal patterns in planta: KCN induced higher Arum-type arbuscule density, positive MGD but lower root colonization compared to SHAM, which favored Paris-type formation and negative MGD. Following our results and current state-of-the-art knowledge, we discuss metabolic functions linked to respiration that may occur within mycorrhizal behavior. We highlight potential connections between AOX pathways and fermentation, and we propose new research and mycorrhizal application perspectives.

Keywords: AMF, AOX, COX, phosphorus, mycorrhizal growth dependency, mycorrhizal type, Rhizoglomus irregulare, Solanum tuberosum

Introduction

The political, social and economic context should, in the next years, favor the exploration and exploitation of beneficial soil organisms for crop production. Government policy initiatives (European Directive 2009/128/EC) and consumer demand will lead to alternative production methods in order to reduce the use of phytosanitary products and fertilizer inputs. Thus, agroecological strategies are increasingly explored and recall some basic definitions that (re)integrate the plant in its environment. The soil is the first habitat for plants which continues to interact at all stages of plant’s life cycles (Jeffries et al., 2003). The soil is also one of the main reservoirs of ecosystem services found on Earth, provided by a wide range of microorganisms, including bacteria and some soil fungi, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF; Gianinazzi et al., 2010). The predominant mutualistic symbiotic relationship between AMF and plant roots was established over 400 million years ago (Brundrett, 2002) in more than 200,000 species, which belong to 74% of plant families (van der Heijden et al., 2015). AMF are obligate biotrophs, represented by at least 289 species1 found worldwide under a wide range of ecological conditions. Many positive mycorrhizal effects on host plants have been reported. AMF can (i) improve plant growth by a better transfer of water and inorganic nutrients, especially phosphorus (Smith and Read, 2008); (ii) increase plant-pathogen resistance and plant health (Whipps, 2004; Pozo et al., 2009); (iii) boost plant photosynthesis (Quarles, 1999); (iv) stabilize soil by the excretion of the fungal glycoprotein, glomalin (Rillig and Steinberg, 2002; Bedini et al., 2009); (v) alleviate the impact of abiotic stresses such as cold or heat (Volkmar and Woodbury, 1989; Charest et al., 1993; Zhu et al., 2010, 2011), salinity (Porras-Soriano et al., 2009), drought (Aroca et al., 2007), nutritive starvation (Smith and Read, 2008) or heavy metals (Karimi et al., 2011). In return, it is believed that AMF benefit from the plant’s carbohydrates supply (Bago et al., 2003) associated with the stimulation of fatty acid synthesis in fungal hyphae (Trépanier et al., 2005).

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are probably one of the essential components of the “second green revolution” (Lynch, 2007), but their implementation faces some major difficulties, namely restrictions from plant producer’s perspective, product costs, producer awareness level and variability in mycorrhizal inoculum quality (Vosátka et al., 2008; Ijdo et al., 2011; Berruti et al., 2016). But there are also limitations inherent to the biological system itself since mycorrhizal benefits are not always guaranteed (Vosátka et al., 2008; Ijdo et al., 2011; Malusá et al., 2012) and the physicochemical properties of targeted soils can negatively impact the symbiosis (Smith and Smith, 2011a,b). One of the biggest challenges of mycorrhizal inoculum field application is the high phosphorus (P) content often encountered under conventional cropping, due to P fertilizer input. It is known that high phosphorus concentrations (or its inorganic salt phosphate) systematically inhibit mycorrhizal colonization (Smith and Read, 2008; Breuillin et al., 2010), and the physiological signaling generated by this element appears systemic since foliar application can lead to the same effects (Sanders, 1975; Schreiner and Linderman, 2005; Schreiner, 2010).

Phosphate affects not only the establishment but also the functioning of mycorrhizal symbiosis. Fungal structure development of the internal mycelium can be divided in two general anatomical groups described by Gallaud (1905). The Arum-type consists of characteristic highly branched arbuscules within cortical cells, formed from a short side hyphal branch. The Paris-type is characterized by the development of extensive intracellular coiled hyphae, which spreads from cell to cell sometimes with only low rates of arbuscule-like branch formation. McArthur and Knowles (1992) have shown in potato root that AMF develop preferentially Arum-type under low P while Paris-type occurs under high P. These two mycorrhizal types may act in different ways within plant roots. In rice, the symbiotic phosphate transporter (PT) OsPt11 is preferentially active in arbuscule branches but not around coiled hyphae (Kobae and Hata, 2010). Given that increasing phosphorus concentration is often associated with a decrease of mycorrhizal growth response (MGD; Smith and Smith, 2011a), these data suggest differential plant fitness related to the mycorrhizal type they harbor. Despite numerous studies, there is not yet a complete explanation for the P inhibition. Therefore, there is an urgent need to better understand the physiological bases of this phenomenon in order to define innovative strategies to improve mycorrhizal development and performance, which are sine qua non conditions to realize the mycorrhizal implementation under high P crop field conditions.

One obvious connection between P and organism behavior is the mitochondrial respiration activity, in which P plays a crucial role as energetic component of ATP. In most plants and fungi, the respiration yield is modulated by the electron partitioning flow shared between the cytochrome oxidase (COX) and the alternative oxidase (AOX) pathways that take part in the electron transport chain (Vanlerberghe, 2013). Both transfer electrons to O2 (which results in water formation), but it is usually assumed that AOX is a non-conserving energy pathway because it does not contribute to ATP formation (Vanlerberghe, 2013) and is regulated by the mitochondrial redox status and the glycolytic flux.

In plants, the COX pathway involves cytochrome c reductase, cytochrome c and cytochrome c oxidase enzymes. Whereas cytochrome c (Cytc) is composed of a single small polypeptide, cytochrome c oxidase is a multimeric complex composed of several different subunits, encoded by the mitochondrial and the nuclear genome (Welchen et al., 2002). Subunit Vb (COXVb) is the most conserved among nuclear-encoded subunits (Rizzuto et al., 1991). Cytc is essential for plant growth and survival and the knock-out of both Cytc genes in Arabidopsis is lethal to the plants while they participate for complex IV stability (Welchen et al., 2012). AOX plays an important role during various stress responses (such as P limitation, Sieger et al., 2005; Plaxton and Tran, 2011) and in specific developmental phases, depending on the expressed isoform (Umbach et al., 2006; Zsigmond et al., 2008; Vanlerberghe, 2013). However, its metabolic significance is much less clear but specific metabolic functions must be involved when the AOX pathway is engaged to sustain basal general metabolic processes associated with the a specific redox status (NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H) cell pool in order to cope with energy demand. In this regard, fermentation metabolism activity could play an important role (Sakano, 2001). The best-known function of fermentative metabolism is to recycle NADH to NAD+ to avoid the depletion of the cytosolic NAD+ pool and inhibition of glycolysis when oxidative phosphorylation is impaired (Sakano, 2001). However, no data is available about the importance of these processes in mycorrhizal symbiosis.

In fungi, AOX plays a role in growth regulation and development, resistance, pathogenesis and pathogenicity, and may contribute to fungal ecological fitness (Umbach and Siedow, 2000; Uribe and Khachatourians, 2008; Ruiz et al., 2011; Grahl et al., 2012; Thomazella et al., 2012; Xu T. et al., 2012). Unlike plants, in which AOX form small multigenic families, the analysis of the fungal genomes currently available reveals that a majority of fungal species possessing the AOX pathway have only one gene sequence, with a maximum of three sequences per genome (Mercy et al., 2015).

In particular, very few studies were conducted to elucidate the role of the two electron pathways in AMF, despite their known importance for the growth of many organisms:

- It was shown that the COX1 protein content is increased in hyphae (Besserer et al., 2006) while the transcript level of COXIV is increased in hyphae as compared to spores (Besserer et al., 2008) within days succeeding application of strigolactone analogous (GR24) in Gigaspora rosea. Hyphal development seems, therefore, associated with the COX pathway, and it corresponds to a higher NAD(P)H protein activity (concomitant with an increase in NADH dehydrogenase activity) and ATP production observed at hyphal tip (Besserer et al., 2008).

- Existence of the cyanide-insensitive respiration pathway in AMF was highlighted by the presence of an AOX sequence in Rhizoglomus irregulare genome, close to the Mucoromycotina AOX 1 (Campos et al., 2015; Mercy et al., 2015), but limited functional data were published. By using SHAM as AOX pathway inhibitor, Besserer et al. (2009) suggested a role of AOX during Gigaspora rosea spore germination. Mitochondrial changes (density and respiration) were observed in response to branching factors (Tamasloukht et al., 2003; Besserer et al., 2006), which may suggest a role of the AOX or COX pathways during the pre-symbiotic phase. Campos et al. (2015) observed a coincident of up-regulation of the tomato AOX1 genes and down-regulation of the RiAOX gene during the first six weeks of symbiosis establishment. Expression data obtained under cold-stress conditions showed that the presence of AMF is able to induce an opposite plant mitochondrial respiratory pattern, by potentially reversing the electron route pathway from the AOX to the COX (Liu et al., 2015). Note that the growth regulator abscisic acid (ABA) was shown to play a crucial role in arbuscule formation and functionality (Herrera-Medina et al., 2007; Martin-Rodriguez et al., 2010, 2011; Aroca et al., 2013), while it regulates the AOX gene expression and activity in plants (Finkelstein et al., 1998; Choi et al., 2000; Rook et al., 2006; Giraud et al., 2009; Lynch et al., 2012; Wind et al., 2012). Nevertheless, no roles were clearly defined for the respiratory pathways during spore dormancy or the symbiotic phase.

Although several studies suggest a connection between respiration and P nutrition, little is known about the uptake and transport of P in connection with the respiratory pathways involved. Plant Pi uptake across the plasma membrane is mediated by Pi/H+ symporters belonging to the Pht1 gene family (Bucher, 2007). In mycorrhizal plants, two P uptake pathways were identified: the “direct phosphate uptake” pathway (DPU), mediated by high affinity transporters that are strongly expressed in roots (Smith et al., 2011) and the “mycorrhizal phosphate uptake” pathway (MPU), relying on AM-inducible Pi transporters, crucial for Pi flux across the periarbuscular membrane at the mycorrhizal interface (Javot et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2012). Inorganic phosphate transporters are also present on the inner mitochondrial membrane and are represented by two families: the phosphate/dicarboxylate carrier (DIC) and the phosphate carrier Pht3 (here named ‘MPT’ for mitochondrial phosphate transporter). MPTs deliver most of the Pi required by the mitochondrial ATP synthase complex (Kiiskinen et al., 1997).

This work is an exploration of the functional framework of the cyanide-sensitive and cyanide-insensitive respiration pathways in the mycorrhizal system Solanum tuberosum/Rhizoglomus irregulare (whose genomes are available). To study this complex aspect in a holobiont system, three strategies were developed: the first assay was implemented to study the impact of respiratory inhibitors SHAM (AOX inhibitor) and KCN (COX inhibitor), as well as, two antagonistic phytohormones (ABA and Ga3) on mycorrhizal spore behavior at the pre-symbiotic phase (axenic condition). The second trial was designed to analyze transcript variations of several genes involved in respiration and fermentation pathways using ABA, a phytohormone known to promote the mycorrhizal symbiosis and also known to be one regulator of the AOX pathway. Then, a third assay consisted to set a non-lethal pharmacological approach using KCN and SHAM treatments, under five different phosphorus concentrations. Our data reveal differential mechanisms that shape plant and fungal behavior by affecting yield, plant FW, mycorrhizal type, hyphal development and MGD. We show that the electron flow partitioning is a key determinant in mycorrhizal behavior and mycorrhizal effects, at least in the S. tuberosum/R. irregulare biosystem. We discuss its potential relevance in regard to specific metabolic pathways, notably to fermentation, but also for the mycorrhizal application.

Materials and Methods

Experiment 1: Spore In vitro Assay

Four viable and mature in vitro spores of R. irregulare were deposited on four cardinal directions in Petri dishes filled with water + 3.5% GelriteTM (Duchefa Biochemie, The Netherlands), containing or not ABA (1 mM), Ga3 (1 mM), SHAM (1 or 5 mM) or KCN (1 or 5 mM). Six plates were tested for each treatment and incubated in dark at 28°C in upside down position. At 24 days after inoculation (DAI), hyphal germination patterns were observed and the germination rate was calculated. Spore viability was also assessed by iodonitrotetrazolium salt (INT) and spores, which appeared red due to the presence of formazan, were counted. INT is a marker of mitochondrial activity (Walley and Germida, 1995; Mukerji et al., 2002). It is known that INT reduction (the conversion of INT to formazan by two electrons and two protons) is connected to the electron chain transport (Berridge et al., 2005) but the exact process within cell is not yet clearly identified.

Experiment 2: Effect of ABA-Driven Pre-trial on Mycorrhizal Performance, Respiration, and Fermentation-Related Genes

The aim of this experiment was to study in a small experimental set the variation of some genes involved in the mitochondrial electron chain and fermentation associated with mycorrhizal performances. In vitro S. tuberosum plantlets (cv K19-99-0012) were grown in growth chambers [20°C/17°C (day/night), 16 h d-1 photoperiod, 70% relative humidity and 55 μmol m-2s-1 photon flux density] on MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962), supplemented with 20 g⋅l-1 sucrose, 3.5 g l-1 GelriteTM (Duchefa Biochemie, The Netherlands) adjusted to pH 5.6 before autoclaving (121°C for 15 min). Plantlets were pre-treated or not with ABA, a known promoter of the AOX pathway, added in culture medium to 0.1 mM final concentration.

Ten-day-old in vitro plantlets were transplanted in 1 L pots containing 100% sterilized sand (baked twice in a dry oven, at 120°C for 6 h). Plants were inoculated (M) or not (NM) at transplanting time with 100 in vitro spores of R. irregulare INOQ strain QS69 placed at the vicinity of the root and grown in a glasshouse [Loitze, Germany; 32°C/25°C (day/night), natural light and day (July–August)]. In this way, no direct contact between AMF and ABA treatment could occur. Plants were fertilized once a week with 50 ml of a modified Hoagland’s solution without P (1 ppm P was mixed in the sand during pot preparation). The watering was performed when needed with the same volume for all plants. Precautions were taken to avoid watering the shoots. Potato plant and soil harvesting were conducted at 8 weeks after inoculation (WAI). Plant growth parameters such as the shoot, root, and tuber FW were measured. The evaluation of mycorrhizal development was performed according to Trouvelot et al. (1986) method after root staining with China Ink (Vierheilig et al., 1998). The MGD was calculated for several potato parameters (root, shoot, yield and total biomass FW) according to the following formula (Plenchette et al., 1983): [100∗((M -NM)/M)], expressed as percentage.

Experiment 3: Effect of Different Phosphorus Concentrations and Respiratory Inhibitors on Mycorrhizal Performance

A multifactorial experiment was designed to test the effects of different P concentrations and respiratory chain inhibitors on mycorrhizal and plant parameters. Mycorrhizal inoculum was produced in bed cultures with a mix of three plant species (Trifolium pratense, Zea mays, and S. tuberosum) in sterile sand, containing 92,000 propagules/l [determined by the Most Probable Number of mycorrhizal propagules (MPN) test, Gianinazzi-Pearson et al., 1985]. In vitro potato plantlets were grown in growth chambers as described in the Experiment 2 before being transplanted to a glasshouse [Loitze, Germany; 32°C/25°C (day/night), natural light and day (July–August)] and grown for 8 weeks in 1 L pots containing 100% sterilized sand (baked twice in a dry oven, at 120°C for 6 h). Plants were inoculated or not with R. irregulare (INOQ strain QS69) at transplanting time, by mixing 4% of a mycorrhizal inoculum containing spores and mycorrhizal root fragments in the growth substrate.

Five P concentrations were tested: 1, 10, 50, 100, and 300 ppm P (respectively, 0.032, 0.323, 1.614, 3.228, and 9.687 mM as final concentration), corresponding to the concentrations of practical reality in crop field soils (50, 100, and 300 ppm) and in mycorrhizal production under glasshouse conditions (1 and 10 ppm). To achieve those concentrations, KH2PO4 was mixed directly into growth substrate. To test the contribution of each respiratory pathway in mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal plants at each P concentration, two respiratory chain inhibitors were used: KCN and SHAM (0.1 mM), which inhibit COX and AOX, respectively. The inhibitors were dissolved in sterile water and added to substrate at 08:00 a.m. in one application 7 DAI, which corresponds to the end of the acclimatization period. The experimental design for the inhibitor studies included (1) non-treated plants, non-inoculated (NM) and inoculated plants (M); (2) KCN treated plants that were non-inoculated (KCN) or inoculated (M KCN) plants; (3) SHAM treated plants that were non-inoculated (SHAM) or inoculated (M SHAM) plants. Plants were fertilized once a week with 50 ml of a modified Hoagland’s solution without P, and were watered as needed with the same volume for all plants. Precautions were taken to avoid watering and treating the shoots.

Potato plant and soil harvesting were conducted at 8 WAI. Plant growth parameters including the shoot, root, and tuber FW, were measured. The evaluation of mycorrhizal development was performed according to the Trouvelot et al. (1986) method after root staining with China Ink (Vierheilig et al., 1998). Parameters investigated (by observing with a microscope 30 root fragments slide per sample) included frequency of mycorrhiza (F %), intensity of mycorrhiza, arbuscule, vesicle and intraradical hyphal colonization in whole root system (respectively, M %, A %, V %, and H %) and within mycorrhizal root fragments (respectively, m %, a %, v %, and h %). The spore production was evaluated in M plants for each repetition by isolating and counting spores after performing the wet sieving method (Gerdemann and Nicolson, 1963) using 3 × 10 g of dried substrate. The MGD was calculated for several potato parameters (root, shoot, yield, and total biomass FW) according to the following formula (Plenchette et al., 1983): [100∗((M – NM)/M)], expressed as percentage. The % FW of root, shoot or tuber was calculated as follows: [Plant organ (root, shoot part or tuber FW)/Total FW] × 100.

Bioinformatic Analyses

Transcript accumulation analyses of plant and fungal genes involved in respiration, nutrient transport and fermentation were performed. Genes of interest are listed in Supplementary Table S1. To obtain the sequences of some targeted genes, a database search was performed using the R. irregulare and S. tuberosum genomes databases2,3 and the INRA Glomus database4. Full-length amino acid sequences of R. irregulare, S. tuberosum and those from fungi and plants were acquired from the JGI database5 and GenBank6 and were aligned by CLUSTALW and imported into the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) package version 6 (Tamura et al., 2013). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method implemented in MEGA with the pairwise deletion option for handling alignment gaps and with the Poisson correction model for distance computation. Bootstrap tests were conducted using 1000 replicates.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For both glasshouse trials, 100 mg of root samples were stored in RNAlater (Qiagen) solution at the time of harvest. Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of roots conserved in RNAlater (Qiagen) using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA synthesis was performed with an oligo(dT) primer (Promega) and reverse transcriptase (MasterscriptTM Kit, 5 Prime, Germany) using 250 ng of total RNA. The cDNAs were 1:10 diluted and amplified using the 7500/7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems®, USA). Amplification reactions were prepared using a SYBR Green PCR Master kit (Maxima) SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) using the following concentrations: 6 μl of PCR water, 9 μL of 2x Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) 0.5 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 mM) and 2 μl of the cDNA template. Three independent biological replicates were analyzed per treatment and each sample was analyzed in duplicate. The specificity of the different amplicons was checked by a melting curve analysis at the end of the amplification protocol. Several candidates were evaluated for further use as reference gene for normalization of the transcript data of target genes, comprising a set of housekeeping genes, rRNA genes and other sequences (data not shown). After evaluation of expression stability using the applications BestKeeper and NormFinder (Andersen et al., 2004; Pfaffl et al., 2004), two genes for potato (StEF1α and StUbc, Gallou, 2011, Supplementary Table S1) and one genes for R. irregulare (GiICL, Lammers et al., 2001, Supplementary Table S1) were chosen as reference genes for our experimental conditions. Expression of target genes was evaluated by efficiency corrected relative quantification for R. irregulare genes and using the geometric normalization factors for potato where two genes are used for normalization (Pfaffl, 2001; Vandesompele et al., 2002). Standard curves of a fourfold dilution series from pooled cDNAs were used for PCR efficiency calculations. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical Analyses

In the Experiment 1–3, differences in plant and fungal growth parameters and gene expression between treatments were examined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), after log or arcsin transformation of values as indicated in figure legends. Dunnett’s test was conducted to identify significant differences (P < 0.05, symbolized by stars) compared to a specified standard control and Duncan’s multiple range tests were performed to identify significant differences (P < 0.05, symbolized by letters) among P concentrations (after standardization against specified control). Data analysis was performed with the SAS enterprise guide 4.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

In the Experiment 3, the relationships between P concentration and plant or fungal parameters were investigated by least squares stepwise multiple linear regression with replication using experiment-wise type I error rates of 0.05 for coefficients calculated using the Dunn–Šidák method (Ury, 1976). For each fungal parameter, the complete candidate model included up to the third degree of P concentration or of ln P, three qualitative variables binary coded as 0 or 1 for control, KCN, SHAM plus all first and second level interactions between powers of P and qualitative variables. Whenever considered necessary after graphical exploration of the data, modeling was done with fungal variables or P concentration logarithmically, arcsin transformed or not with the major criteria for model selection being the coefficient of determination (data not shown). Lack of fit was tested for P = 0.05 and coefficients of determination (R2) are presented as proportion of the maximum R2 possible (Draper and Smith, 1998). Linear regressions and analyses of variances were done with Statgraphics 4.2 (STSC, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA), all other statistics used in regression were performed in Excel® (Microsoft Corporation). Least squares stepwise multiple linear regression data are given in Supplementary Table S2 (under each fungal parameter) and Supplementary Table S3 (under each plant parameter).

Results

Experiment 1 – Influences of Respiratory Inhibitors and Two Antagonistic Plant Growth Regulators at the Pre-symbiotic Phase

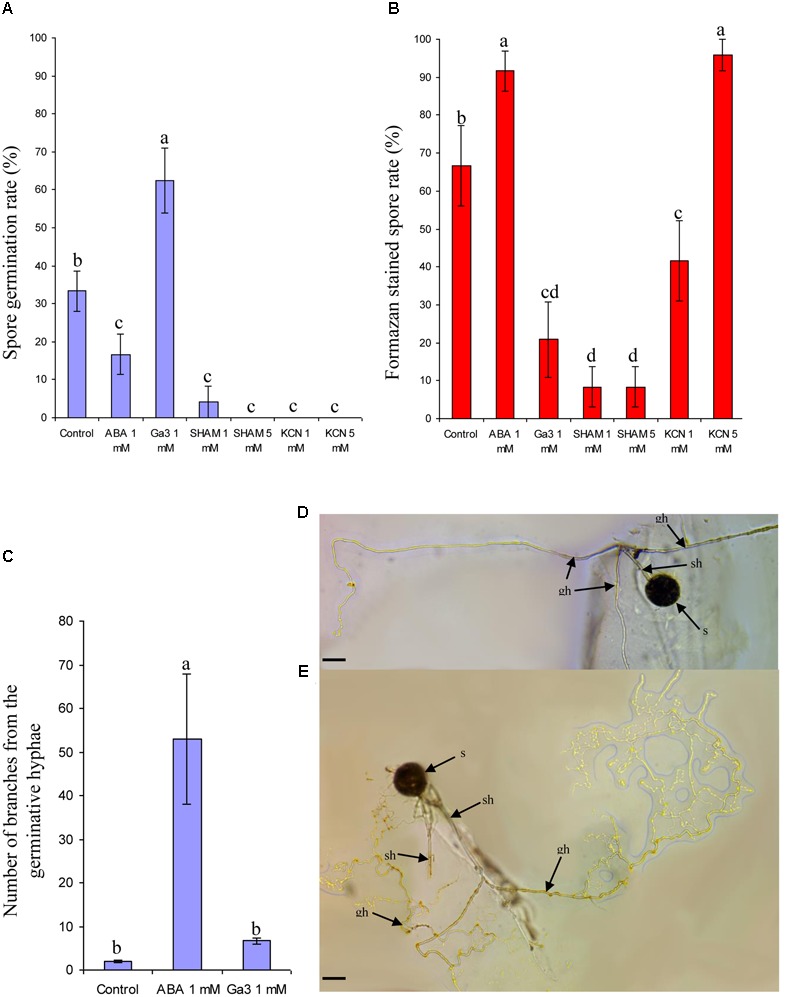

Compared to non-treated spores, ABA treatment decreased the germination rate (Figure 1A) but increased significantly the viable spore fraction (containing formazan crystals, Figure 1B). Ga3 treatment induced an opposite effect (Figures 1A,B). Both SHAM and KCN, at 1 and 5 mM, inhibited spore germination (Figure 1A), but induced an opposite reaction on INT reduction ability (Figure 1B): red stained spores rate was higher in KCN (for both concentrations) than in SHAM at 1 and 5 mM, and also than in non-treated spores (with 5 mM KCN). Then, ABA induced a significant hyphal branching pattern around the germinated spores (Figures 1C,E) compared to spores treated or not with Ga3 (Figures 1C,D).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of two antagonistic plant growth regulators and two respiratory inhibitors on spore germination, spore viability, and germinative hyphal phenotype. Effect of Ga3 (1 mM), ABA (1 mM), SHAM (1 and 5 mM) and KCN (1 and 5 mM) on spore germination (R. irregulare) (A) and spore viability (B), number of branches in the germinative hyphae following or not ABA and Ga 3 treatment (C) with representative germinative straight hyphal pattern under Ga3 treatment (D) or branched hyphal pattern under ABA treatment (E). s, spore; sh, subtending hypha; gh, germinative hypha. Data show means (n = 24) ± SE Treatments with the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05 SNK multiple-comparison ANOVA), after arcsin transformation of percentage values. Scale bar: 50 μm. Data analysis was performed with the SAS enterprise guide 4.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Gene Sets for Transcriptomic Study in Experiments 2 and 3

The bioinformatic analyses conducted in this study revealed that the AOX family of S. tuberosum is composed of three AOX1 and one AOX2 sequences, called, respectively, StAOX1a, StAOX1b, StAOX1d and StAOX2 according to the AOX classification proposed by Costa et al. (2014). All StAOX isoforms were expressed but harbored tissue specificity in our experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure S3). The R. irregulare genome contained one single AOX sequence (RiAOX).

Two isoforms encoding for cytochrome c (StCytc1 and StCytc2) and COXVb (StCOXIVb1 and StCOXIVb2) were found in S. tuberosum genome, but StCytc2 was not expressed in the roots and therefore it was not considered for further analysis (Supplementary Figure S3). The R. irregulare genome contained one single gene encoding for cytochrome c (RiCytc) and COXVb (RiCOXIVb).

The expression of six (StPT1, 2/6, 3, 4, 5, and 8) out of the ten previously described PT genes belonging to the Pht1 family in S. tuberosum (Leggewie et al., 1997; Rausch et al., 2001; Nagy et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2014) was studied. The expression of StPT2 and StPT6 was not dissociable and was considered as a sum StPT2/6. These two genes shared a very high sequence similarity and are tandemly organized on chromosome 3. On chromosome 6, only two complete sequences were found in potato: StPT7 sequence was incomplete and could not be reconstructed in silico. StPT8, StPT9, and StPT10 were all located in the same region of the chromosome 9. The expression of StPT8, which shares the highest homology with SlPT7 (Chen et al., 2014), was studied. In R. irregulare, the Pht1 family was divided into four different clusters named after the S. cerevisiae sequences therein (Supplementary Figure S4). ScPHO84-like cluster groups had putative high affinity P transporters as ScPHO84 and contained four putative R. irregulare sequences previously described (RiPT1, RiPT2, RiPT3, and RiPT4; Fiorilli et al., 2013; Walder et al., 2016). We found complete and functional sequences only for RiPT1 and RiPT3. Within the putative low affinity P transporters, grouping with the yeast transporters ScPHO87 and ScPHO90 described by Pinson et al. (2004), only one R. irregulare gene was found (RiPT7). The third cluster groups sequences presented homology with the S. cerevisiae high affinity Na+/Pi cotransporter ScPHO89 (Sengottaiyan et al., 2013) and two R. irregulare sequences (RiPT5 and RiPT6). RiPT6 presented an incomplete sequence and no expression in our experimental conditions. The last cluster contained ScPHO88-like sequences, which were much shorter (about 189 aa) and did not present a transport activity. One R. irregulare gene matched with this sequence (RiPT8), but as it did not encode a functional transporter, the transcription of this gene was not monitored in this study.

Concerning mitochondrial P transport, four gene sequences encoding a transporter were found in S. tuberosum genome, and one R. irregulare in genome (Supplementary Figure S5). In potato, three of the four genes were expressed in roots (StMPT1a, StMPT1b, and StMPT3). StMPT2 was found to be expressed only in fruits in our experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure S3).

Then, two ldh and three pdc sequences were found in potato genome (Supplementary Figures S6 and S7). It was noted that transcript level was higher for StLDH expression than for StPDC in root, comparing relative values. One ldh sequence was found in the R. irregulare genome (RiLDH).

Experiment 2: Influence of ABA on Mycorrhizal Behavior and Expression Pattern of Genes Involved in Mitochondrial Electron Chain

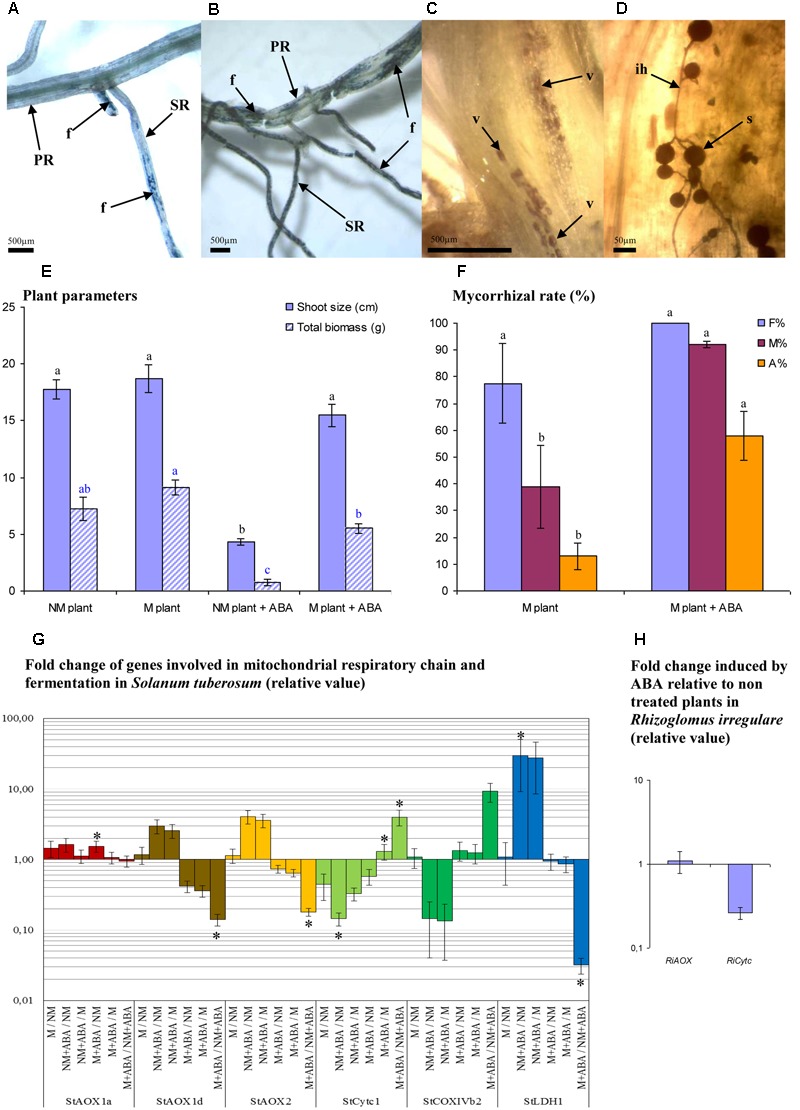

Following ABA pretreatment, mycorrhizal structures were observed in the primary adventitious root and even in the stem base (Figures 2A–D), which seems to be a rare case in potato roots under normal conditions (Mercy – non-published observation). AMF increased plant total FW biomass in non-pretreated plants by 1.26-fold (MGD = 20.6%) and in ABA pretreated plants by 7.33 (MGD = 86.4%). Pretreatment with ABA during the in vitro phase induced a long-term effect, since a strong plant growth depression was observed (in NM plants, Figure 2E). Mycorrhizal colonization and arbuscule intensity were significantly promoted within ABA pretreated plants (Figure 2F) compared to non-pretreated plants, consistent with observations performed on tomato plants (Herrera-Medina et al., 2007).

FIGURE 2.

Influence of ABA on mycorrhizal development and gene expression involved in electron partitioning. Mycorrhizal development (R. irregulare) observed at 8 WAI in potato roots (cv. KK19–0012) pre–treated or not with ABA (0.1 mM) during the in vitro phase culture. (A) typical fungal development in plants non-treated with ABA (B) typical fungal development in plants pretreated with ABA; (C,D) mycorrhizal development on a stem of ABA pretreated plant; (E) growth parameters of potato plant inoculated or not with R. irregulare after ABA pretreatment or not (8 WAI); (F) mycorrhizal rate between inoculated plant treated (M plant + ABA) or not pretreated (M plant) with ABA; (G,H): expression pattern of genes involved in electron partitioning. PR, primary adventitious root; SR, secondary adventitious root; f, mycorrhizal structure; v, vesicle; s, spore; ih, intraradical hypha; F%, frequency of mycorrhizal development in root system; M%, intensity of mycorrhizal development in the root; A%, intensity of arbuscule development in whole root system. For plant and fungal parameters, treatments with the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05 SNK multiple-comparison ANOVA, n = 4). Statistical tests were performed separately for each plant parameters and each fungal parameters, after arcsin transformation for percentage values. For expression data (G,H), significant difference are indicated by stars above graphs (∗P < 0.05). Data analysis was performed with the SAS enterprise guide 4.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The expression analyses of genes involved in the respiratory chain revealed that StAOX1d and StAOX2 were significantly down-regulated while StCytc1 was significantly up-regulated in M versus NM plants in presence of ABA (Figure 2G). The expression of these genes remained unaffected by the presence of AMF and in the absence of treatment. Comparing to NM and M non-treated plants, ABA treatment induced similar trends of up-regulation for StAOX1d and StAOX2 (although changes are not significant), while StCytc1 was down-regulated (significant when comparing NM plants). Contrasting with this observation, the presence of AMF in ABA plants induced significant down-regulation for StAOX1d and StAOX2 and up-regulation for StCytc1 (significant) and CoxIVb2 (tendency) when compared to non-inoculated ABA plants. It was observed a strong up regulation of StLDH1 induced by ABA compared to non-treated plants, inoculated (tendency) or not (significant). This gene was significantly down-regulated in presence of AMF (within ABA plants group). Regarding RiAOX and RiCytc (Figure 2H), no significant effect induced by ABA was observed, although RiCytc tended to be down-regulated.

Experiment 3

The Fungal Colonization Is Influenced by Phosphorus Level and Respiratory Inhibitors

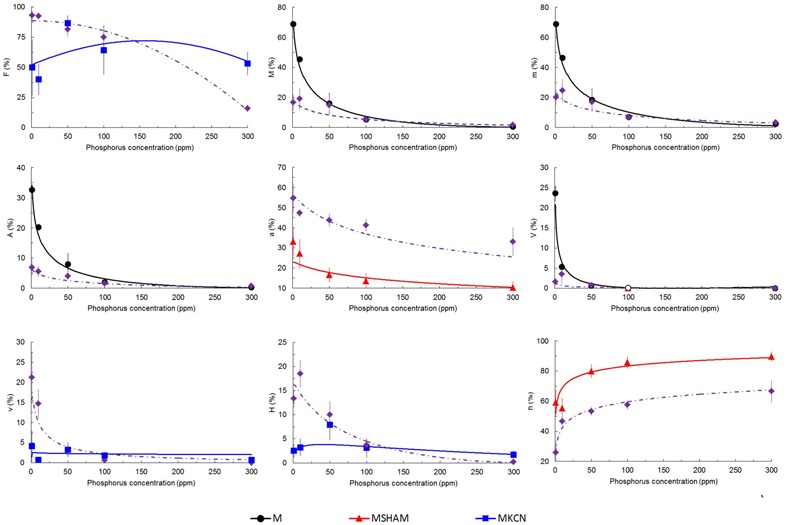

Fungal phenotypic data are indicated in Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S1. The mycorrhizal colonization decreased with increasing P concentrations in all treatments. Many fungal structures, such as hyphae, arbuscules, vesicles, and frequency of mycorrhiza, were affected by KCN and SHAM, especially under low P concentration (1 and 10 ppm, Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S1). Compared to non-treated mycorrhizal plants (M plants), SHAM treatment significantly reduced the arbuscule (A %) formation to the benefit of an enhanced intraradical hyphal development (h %, Figure 3). KCN treatment strongly inhibited the fungal development at 1 and 10 ppm P (Supplementary Figure S1), but a significant higher a % was observed (Figure 3) compared to SHAM among P concentrations. At 300 ppm P, highest values were observed for almost all fungal parameters under KCN treatment (Supplementary Figure S1). Hyphal development (H %) in M KCN was reduced compared to M and M SHAM plants at 1 and 10 ppm P (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Predicted and observed (means ± SE) mycorrhizal rate parameters of potato plants treated with respiratory chain inhibitors or not, inoculated with R. irregulare under five phosphorus concentrations. Parameters estimated according to Trouvelot et al. (1986) in potato roots inoculated with R. irregulare, harvested at 8 WAI. Plantlets not treated (M, black continuous lines and closed circles), treated by SHAM (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM; red continuous lines and closed triangles) or by KCN (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM; blue continuous lines and closed squares) through five phosphorus concentrations (harvesting at 8 WAI, n = 3). Whenever treatments did not differ significantly they are represented together as one line by purple dots and dashed lines and closed diamonds. F%, frequency of mycorrhizal development in root system; M%, intensity of the mycorrhizal development in roots; m%, intensity of mycorrhizal development in mycorrhizal root fragments; A%, intensity of arbuscules in whole root system; a%, intensity of arbuscules in mycorrhizal root fragments; V%, intensity of vesicles in whole root system; v%, intensity of vesicles in mycorrhizal root fragments; H%, intensity of hyphal development in whole root system; h%, intensity of hyphal development in mycorrhizal root fragments. Linear regressions and analyses of variances were done with Statgraphics 4.2 (STSC, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA), all other statistics used in regression were performed in Excel® (Microsoft Corporation). Regression coefficients after solving the overall equation fitted are shown in the Supplementary Table S2.

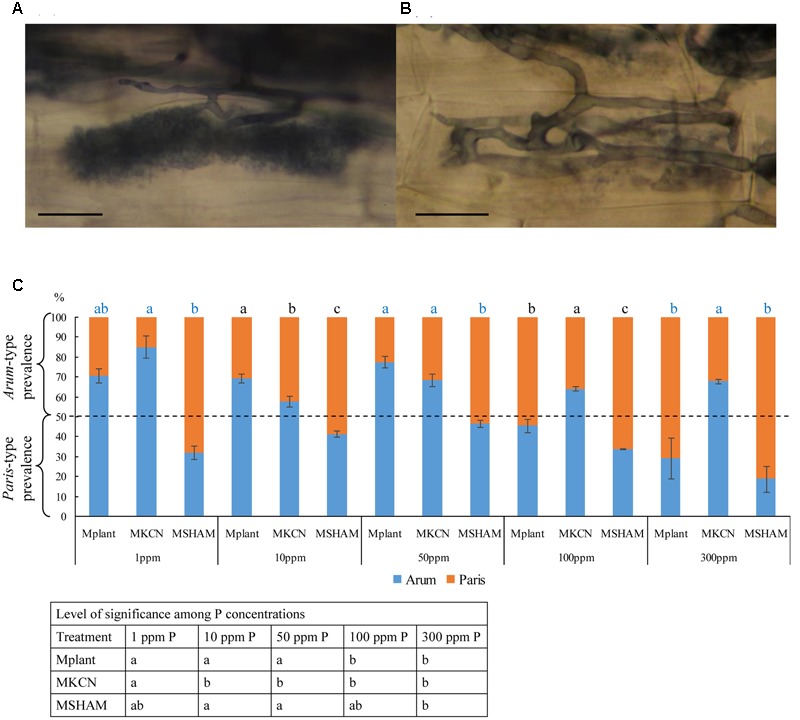

The Mycorrhizal Type Is Influenced by Phosphorus Level and Respiratory Inhibitors

Both Arum-type and Paris-type structures were observed in roots (Figures 4A,B, respectively) across the different treatments, and their occurrences were influenced by both P concentrations and respiratory chain inhibitors (Figure 4C). In M plants, Arum-type predominated under low P concentrations (1 to 50 ppm) while Paris-type predominated at high P concentration (300 ppm). The application of both respiratory inhibitors suppressed this P influence. SHAM treatment induced a disorganization of arbuscule branching similar to the effect of a high P concentration (300 ppm P) in non-treated plants and Paris-type hyphal development was predominant for all P concentrations. Under KCN treatment, Arum-type was predominant for all P concentrations. The occurrence of Arum-type in KCN was significant compared to Paris-type in SHAM for all P concentrations.

FIGURE 4.

Mycorrhizal type’s prevalence within potato roots, following treatments or not with respiratory chain inhibitors, under five phosphorus concentrations. Mycorrhizal types within potato roots: (A) Arum-type, (B) Paris-type (staining: China Ink); (C) percentages of mycorrhizal type distribution under five different phosphorus concentrations in non-treated control plants and plants treated by respiratory inhibitors. Scale bar: 10 μm. Data show means (n = 3) ± SE. Treatments with the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range tests ANOVA). Statistical tests were performed after arcsin transformation of percentage values. The level of significance among treatment per P concentration is given above the graphs, and the one among P concentrations for a given treatment is indicated in the table below graph. Data analysis was performed with the SAS enterprise guide 4.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

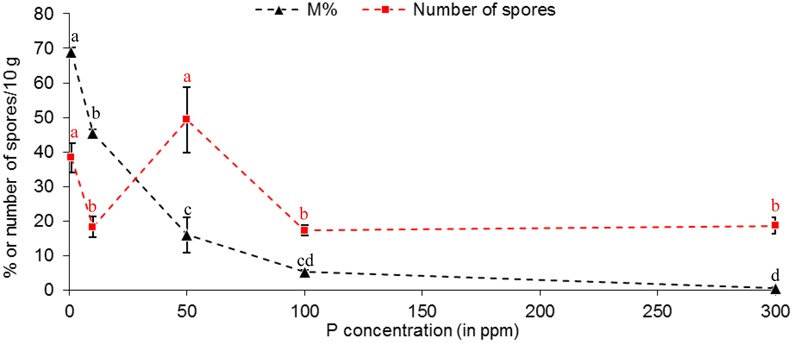

The Spore Production Is not Linked to either with P Concentrations, nor with Mycorrhizal Rate

A maximum number of spores was observed at 50 ppm P (Figure 5), and then in a lesser extent, at 1 ppm. The number of spores produced at 10, 100 and 300 ppm P was similar, and significantly lower than at 1 and 50 ppm P. No correlation between spore production and P concentration was observed (r2 = 0.1834). No correlation between spore production and any mycorrhizal parameters was observed among P concentrations, which might indicate the involvement of at least two different metabolic determinants. We noticed that highest values for spore number, a % and Arum-type were obtained at 1 and 50 ppm P.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of phosphorus concentrations in non-treated plants on mycorrhizal sporulation, compared to mycorrhizal development in root. R. irregulare spore number in 10 g of substrate and intensity of mycorrhiza in root (M%, added only to visualize the differences with sporulation profile) at 8WAI through phosphorus concentration after inoculation of potato in vitro plantlets. Data show means (n = 3) ± SE. Treatments with the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range tests ANOVA). Statistical tests were performed separately for each fungal parameter, and after arcsin transformation of percentage values (M %). Data analysis was performed with the SAS enterprise guide 4.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

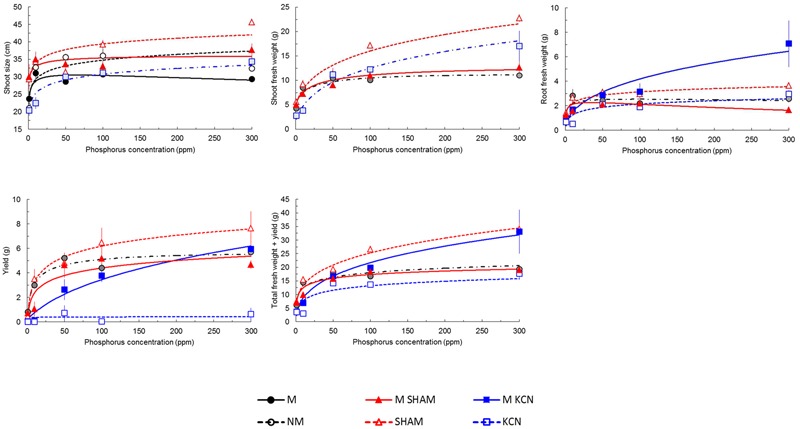

Respiratory Chain Inhibitors Reveal Opposite Plant Performance between Inoculated and Non-inoculated Plants

Plant phenotypic data are indicated in Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S2. Presence of AMF in non-treated plants induced few specific responses to P concentrations on plant vegetative parameters including shoot and root biomass, yield and total biomass. Only shoot size was significantly promoted among P concentrations (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Predicted and observed (means ± SE) of potato in vitro plantlets growth parameters treated with respiratory chain inhibitors or not and inoculated or not with R. irregulare under five phosphorus concentrations. Plantlets were inoculated (M, black continuous lines and closed circles) or not (NM, black dashed lines and open circles) with R. irregulare, treated by SHAM (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) and inoculated (M SHAM, red continuous lines and closed triangles) or not (SHAM, red dashed lines and open triangles), and treated by KCN (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) and inoculated (M KCN, blue continuous lines and closed squares) or not (KCN, blue dashed lines and open squares) through five phosphorus concentrations (harvesting at 8 WAI, n = 3). Whenever M and NM treatments did not differ significantly for a given treatment same colors and symbols were used except that dots and dashed lines and half tone symbols were used. Linear regressions and analyses of variances were done with Statgraphics 4.2 (STSC, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA), all other statistics used in regression were performed in Excel® (Microsoft Corporation). Regression coefficients after solving the overall equation fitted are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Under KCN treatment, the presence of AMF significantly improved all vegetative plant parameters under all P concentrations, whereas under SHAM treatment, root biomass, yield and total biomass were decreased (Figure 6). Thus, KCN and SHAM treatments had opposite effects when comparing inoculated and non-inoculated plants for yield and FW total biomass. M KCN plants showed the highest root FW values at 300 ppm P with an increase of 2.34- and 4.24-fold, respectively, compared to M and M SHAM plants (Supplementary Figure S2).

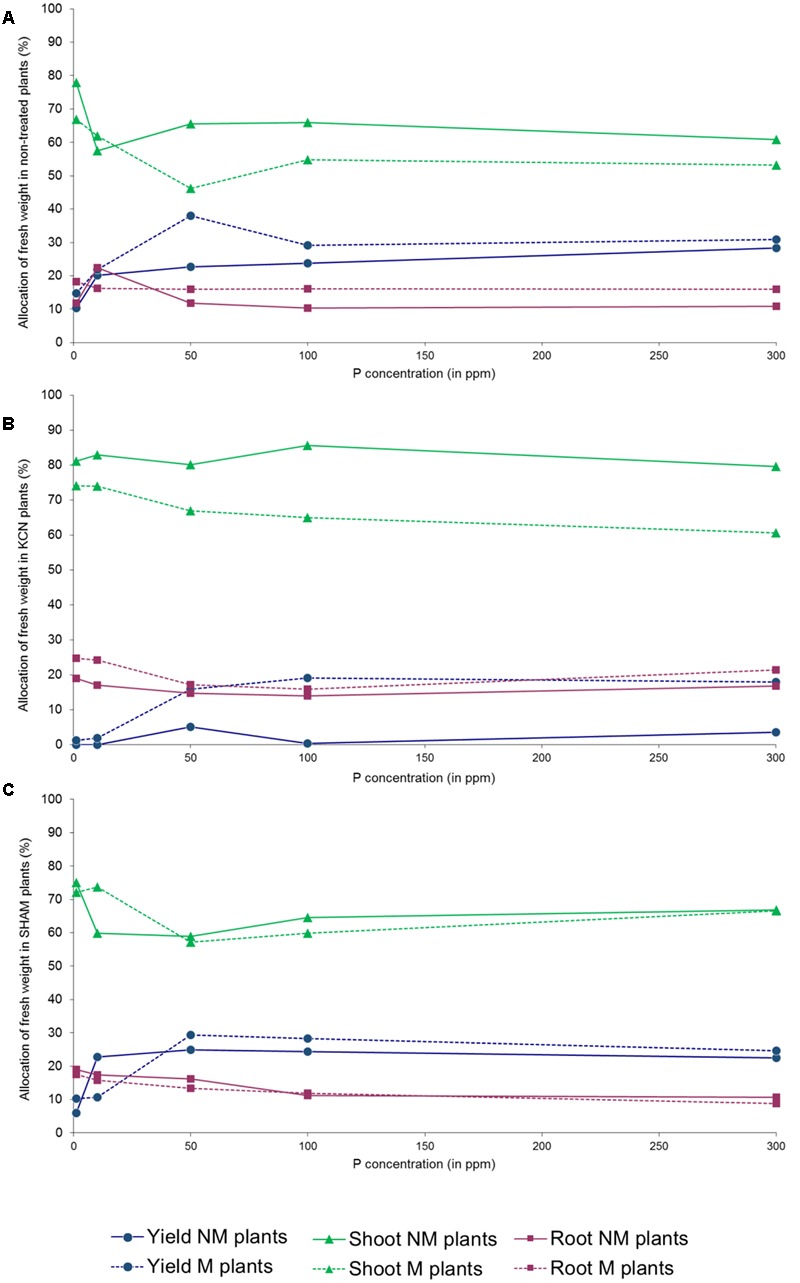

We noticed that the tuber FW yield was not proportional to P concentrations in several treatments (Supplementary Figure S2): a peak was observed in NM, M and KCN plants at 50 ppm P, while maximum values were obtained at 100 ppm P in M SHAM plants. Similarly, the total biomass FW increase among P concentration was not proportional in NM plants where a peak was observed at 50 ppm P, but not in M plants. FW biomass data revealed that AMF had an impact on plant FW biomass partitioning (Figures 7A–C). The percentage of FW attributed to the root part was relatively stable for a given treatment among P concentrations, with the exception of NM plants (Figure 7A) at 10 ppm (higher value). When non-treated plants were inoculated with AMF, the profile of the FW percentage attributed to the shoot was opposite to the one attributed to the tuber yield and an anomaly was observed at 50 ppm P. In all treatments and P concentrations, except SHAM plants at 10 ppm P, the presence of AMF enhanced FW biomass allocation to the yield, to the detriment of the shoot.

FIGURE 7.

Percentage of FW attributed to the shoot, root and tuber in potato in vitro plantlets. Plants are inoculated with R. irregulare (A) without treatment; (B) treated by KCN (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM); (C) treated by SHAM (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) through five phosphorus concentrations (data obtained after 8 WAI).

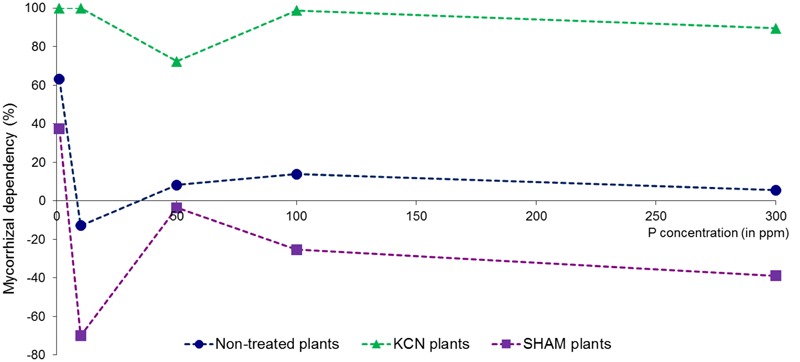

Impact of Respiratory Inhibitors on the Mycorrhizal Yield Dependency

The mycorrhizal dependency was affected by P in M plants without any direct correlation with the concentration (Figure 8), as the maximum value was observed at 1 ppm P (63.05%) and the lowest at 10 ppm P (-12.48%). The higher P concentration yielded low but positive values. The mycorrhizal dependency presented an opposite pattern between KCN and SHAM treatments. The yield formed under KCN conditions was almost totally dependent (close to 100%) of the presence of AMF, and the lowest value was observed at 50 ppm. In contrast, with the exception of 1 ppm P, a negative mycorrhizal yield response was observed in SHAM treatment in all P concentrations tested.

FIGURE 8.

Mycorrhizal growth dependency (yield) in potato in vitro plantlets. Plants are inoculated with R. irregulare without treatment or treated by SHAM (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) or treated by KCN (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) through five phosphorus concentrations (data obtained after 8 WAI).

Modulation of Genes Involved in Mitochondrial Electron Chain and Fermentation by Phosphorus and Respiratory Inhibitors

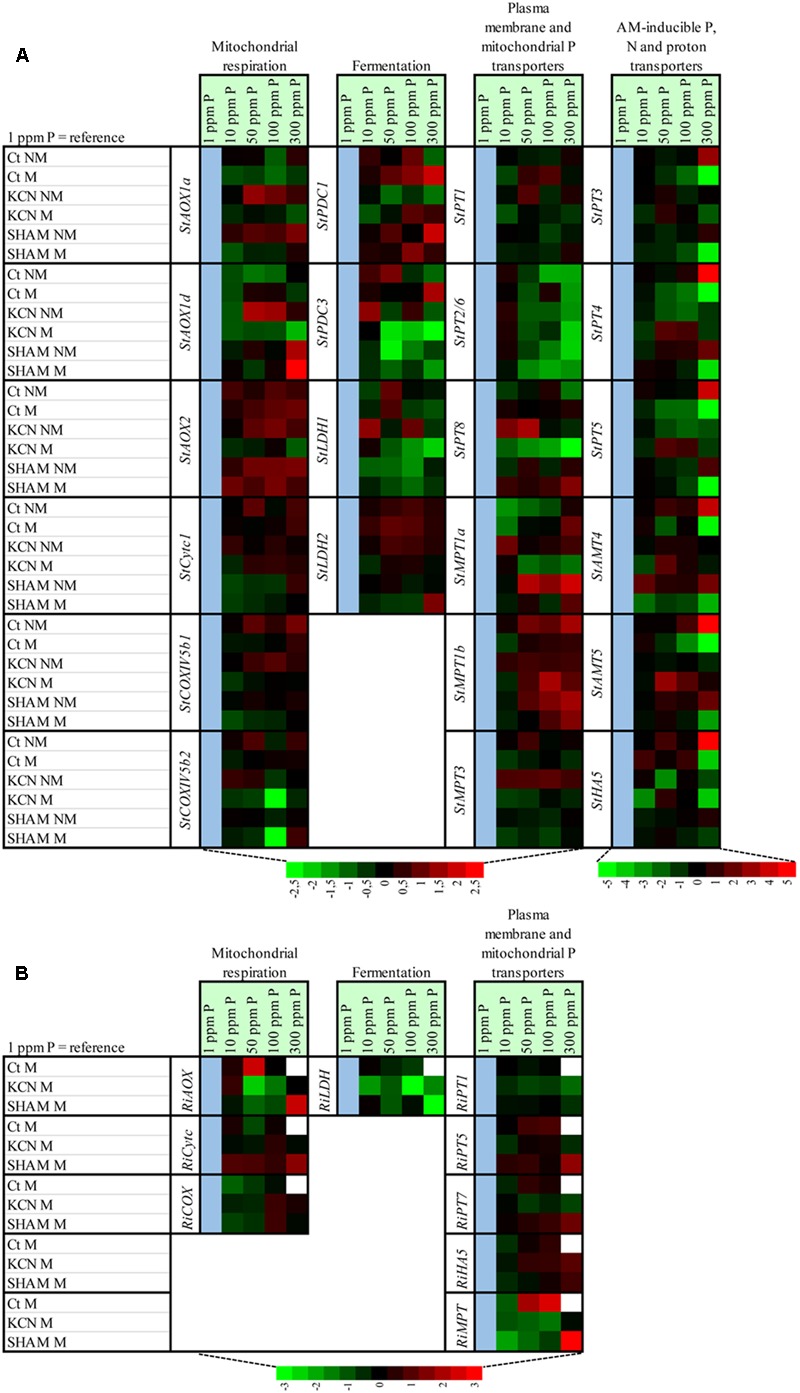

Variation of the expression of genes involved in the respiratory chain and fermentation among P concentrations (1 ppm used as reference) for each treatment, in potato and R. irregulare, are indicated in Figure 9 and Supplementary Figures S8, S9.

FIGURE 9.

Heat map showing the effect of P concentration on the relative expression of genes involved in mitochondrial respiratory chain, fermentation, phosphorus, nitrogen and proton plasma membrane transporters and mitochondrial phosphorus transporters in potato root and in R. irregulare, following inoculation or not of AMF, treatment or not with two respiratory inhibitors through two phosphorus concentrations. The heat map shows the real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis results of genes involved in mitochondrial respiratory chain (three StAOX isoforms, StCytc1, StCOXVb1, StCOXVb2, RiAOX, RiCytc, and RiCOXIVb), fermentation (two StPDC and two StLDH isoforms and RiLDH), phosphorus, nitrogen and proton plasma membrane transporters (six StPT isoforms, two StAMT isoforms, StHA1, three RiPT isoforms and RiHA5) and mitochondrial phosphorus transporters (three StMPT isoforms and RiMPT) in potato root (A) and in R. irregulare (B), under five phosphorus concentrations and following treatment by KCN (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) or SHAM (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) or not treated (Ct). Plants were inoculated (M) or not (NM) by R. irregulare. The expression levels of genes are presented using fold-change values transformed to Log2 format compared to 1 ppm P as reference (cell in blue). White cells correspond to non-determined analyses. The Log2 (fold-change values) and the color scale are shown at the bottom of heat map.

At plant side, data showed that the regulation pattern from genes encoding for AOX, COX, or fermentation pathways were mostly specific to the P concentration (such as a down-regulation of StAOX1a at 100 ppm in NM plants, an up-regulation of StAOX1d in NM KCN plants at 50 ppm or a down-regulation of StCOXIVb2 in M SHAM plants at 100 ppm). We noticed that a significant common up-regulation was observed at 50 ppm P for genes involved in cytochrome pathway (StCytc1, StCOXVb1-2) in non-inoculated plants but not in inoculated plants (non-treated group). Specific responses to P concentration were also noted for genes involved in fermentation. We observed that StPDC1 in M plants was more expressed and StLDH1 was more repressed in M KCN with increasing P concentrations.

Within R. irregulare, some transcript variations were observed at specific P concentrations but the tested genes were mostly unaffected. In M plants, when compared to 1 ppm P, a significant up-regulation was observed at 50 ppm for RiAOX, while RiCytc harboured an opposite profile pattern (although not significant). These data were concomitant with the highest sporulation (Figure 5). In contrast with non-treated conditions, a significant down-regulation was observed at 50 ppm for RiAOX in M KCN plants. It is noteworthy that no detection was obtained at 300 ppm P from M plants.

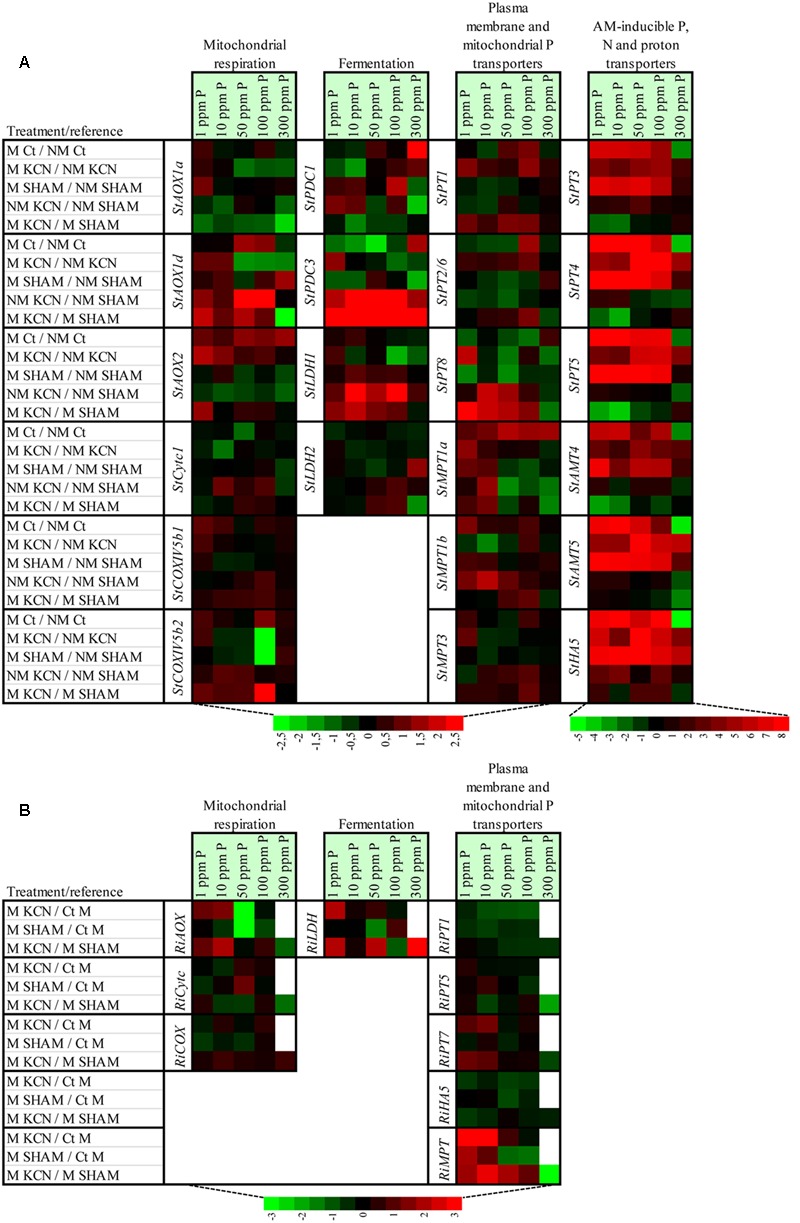

Variation of the expression of genes involved in the respiratory chain and fermentation between treatments (non-inoculated plants used as reference) for each P concentration, in potato and R. irregulare, are indicated in Figure 10 and Supplementary Figures S10, S11.

FIGURE 10.

Heat map showing the effect of treatments on the relative expression of genes involved in mitochondrial respiratory chain, fermentation, phosphorus, nitrogen and proton plasma membrane transporters and mitochondrial phosphorus transporters in potato root and in R. irregulare, following inoculation or not of AMF, treatment or not with two respiratory inhibitors through five phosphorus concentrations. The heat map shows the real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis results of genes involved in mitochondrial respiratory chain (three StAOX isoforms, StCytc1, StCOXVb1, StCOXVb2, RiAOX, RiCytc and RiCOXIVb), fermentation (two StPDC and two StLDH isoforms and RiLDH), phosphorus, nitrogen and proton plasma membrane transporters (six StPT isoforms, two StAMT isoforms, StHA1, three RiPT isoforms and RiHA5) and mitochondrial phosphorus transporters (three StMPT isoforms and RiMPT) in potato root (A) and in R. irregulare (B), under five phosphorus concentrations and following treatment by KCN (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM) or SHAM (at 7 DAI – 0.1 mM), or not treated (Ct). Plants were inoculated (M) or not (NM) by R. irregulare. The expression levels of genes are presented using fold-change values transformed to Log2 format compared to mentioned treatment in the table. White cells correspond to non-determined analyses. The Log2 (fold-change values) and the color scale are shown at the bottom of heat map.

In potato, transcript responses for genes encoding for enzymes involved in the AOX and COX pathways were mostly specific to P concentration. In particular, the presence of AMF compared to their absence (non-treated plants) at 50 ppm P induced an up-regulation of StAOX2 but a down-regulation of StCytc1. Effect of treatments on the expression of genes involved in fermentation pathway were also specific to P concentration. Significant up-regulation was observed for StPDC1 and StLDH1 when comparing KCN to SHAM treatments (in plants inoculated or not), but with some specificities regarding P concentrations.

In the fungus, expression levels of RiAOX, RiCytc, or RiCOXIVb appeared mostly constitutive when comparing KCN to SHAM treatments. In contrast, KCN induced significant strong up-regulation of RiLDH at 1, 50, and 300 ppm P compared to SHAM.

To summarize, the inoculation or the use of respiratory inhibitors induced specific expression patterns for genes encoding for enzymes involved in the AOX and COX pathways, but StAOX isoforms were unexpectedly not highly induced by KCN compared to SHAM treatments. No obvious interpretation can be easily deduced from these data, underlining complex regulations that were contrasted with those obtained in the Experiment 2. We noticed, nevertheless, that KCN seemed to induce a higher fermentation context compared to SHAM, within potato (inoculated or not) and also in R. irregulare.

Several correlations were found between expression of genes and fungal parameters in non-treated plants (Supplementary Table S4) or treated with KCN (Supplementary Table S5) or with SHAM (Supplementary Table S6). Significant negative correlations were observed between M %, m %, A %, and V % and StAOX2, but a positive correlation with the H % parameter (non-treated plants) was found. Significant negative correlations were also noticed between StCytc1 and F % and a %, between StCOXVb1 and F % and between StCOXVb2 and h %. Under KCN, positive correlations were observed between StAOX1a and A % and V % and also between StAOX1d and A % but a negative correlation between StAOX1d and H % was detected. Under SHAM, a significant negative correlation was found between F % and StAOX1d. No correlation was found between tested genes involved in AOX or COX pathway with mycorrhizal responses on plant phenotype in any treatment.

Modulation of Genes Involved in Nutrient and Proton Transport by Phosphorus and Respiratory Inhibitors

Variation of the expression of genes involved in nutrient and proton transport among P concentrations (1 ppm used as reference) for each treatment, in potato and R. irregulare, are indicated in Figure 9 and Supplementary Figures S8, S9.

In potato, a common expression pattern was observed at 300 ppm P for StPT3, StPT4, StPT5, StAMT4, StAMT5, and StHA5, which were up-regulated in NM plants but repressed in M plants. This response was much less pronounced in plants inoculated and treated with SHAM and disappeared in the other treatments (NM KCN, M KCN, and NM SHAM). StPT1 remained mostly unaffected by inoculation or treatment, StPT2/6 was down-regulated by high P in M plants treated or not with respiratory inhibitors, but also in NM SHAM plants. Some specific responses were obtained depending on P concentration and treatment for StPT8.

Concerning mitochondrial P transport, StMPT1a expression in NM plants tended to increase with P concentration, from 10 to 300 ppm P, although no significant variations were observed when comparing the various P concentrations to 1 ppm P. SHAM treatment tended to up-regulate this gene at high P concentrations (50 to 300 ppm). StMPT1b was up-regulated by high P in plants non-treated (non-inoculated) or treated by SHAM (inoculated or not).

Variation of the expression of genes involved in nutrient and proton transport between treatments (non-inoculated plants used as reference) for each P concentration, in potato and R. irregulare, are indicated in Figure 10 and Supplementary Figures S10, S11.

At plant side, as common response, the presence of AMF, in plants treated or not with respiratory inhibitors, up-regulated the expression of StPT3, StPT4, StPT5, StAMT4, StAMT5, and StHA5 for all P concentrations, except at 300 ppm within non-treated plants. Such strong responses were not found for StPT1, StPT2/6, and StPT8 in any treatment. In KCN plants, presence of AMF was associated with up-regulation of StPT1 at 1, 50, and 100 ppm P and StPT2/6 at 100 ppm P, compared to plants treated or not with SHAM. Significant strong correlations were found between AM-inducible P transporters and M % or A % (in plants treated or not with SHAM, Supplementary Tables S4, S6) but most of these correlations were not observed in plants treated with KCN (Supplementary Table S5). Tested genes involved in mitochondrial transport were up-regulated in presence of AMF in non-treated plants in all P concentrations, but responses were specific to the isoform. In the presence of respiratory inhibitors, their expression patterns were more complex with specific responses regarding P concentration.

The expressions of RiPT1, RiPT7, and RiHA5 were monitored in this study and highlighted that there were no transcript level changes across all treatments and P concentrations (Figure 9). Only RiPT5 was induced at high P conditions with an up-regulation at 50 and 100 ppm P in control conditions. Regarding RiMPT, when compared to 1 ppm P, a significant up-regulation was observed at 300 ppm P (Figure 9) in plants treated with SHAM, and non-treated plants at 100 ppm P, and a significant down-regulation was observed at 300 ppm when comparing KCN to SHAM (Figure 10).

Discussion

Mitochondrial Respiratory Inhibitors Influence Fungal Behavior at Pre-symbiotic Phase

Dormancy is often related to AOX pathway in plant seeds, but also in fungi. Several examples have been reported, especially within Mucoromycotina (Cano-Canchola et al., 1988; Salcedo-Hernandez et al., 1994) which are phylogenetically closely related to AMF (Hibbett et al., 2007), showing a respiratory shift characterizing spore germination process from AOX (dormancy) to COX (hyphal growth). It is difficult to define AOX/COX interplay during spore germination in R. irregulare as spores can return into dormancy and germinate again several times without obvious phenotypic signs (Giovanetti et al., 2010), and the hyphal tube germination is the physiological consequence of an already implemented respiratory shift, as shown for Mucor rouxii (Cano-Canchola et al., 1988).

Nevertheless, our data (Experiment 1) with KCN suggest that AOX is very likely involved in spore dormancy. Application of SHAM or KCN inhibited the spore germination, supporting the importance of both electron pathways and a possible involvement of a respiratory shift from AOX to COX. However, further work is needed to confirm this statement. AMF spores are sensitive to plant hormones, and their germination responses harbor opposite patterns between the antagonistic hormones ABA and Ga3, as ABA maintained spore dormancy while Ga3 broke it, similarly to plant seeds (White and Rivin, 2000; Linkies and Leubner-Metzger, 2012). Therefore, these observations support the need to apply ABA as pre-treatment (Experiment 2) and the need to apply the respiratory inhibitors some days after plant inoculation (Experiment 3) in order to not disturb the pre-symbiotic developmental phase of R. irregulare. Promotion of hyphal branching pattern in ABA treatment fits with previous observations: Juge et al. (2002, 2009) showed that spores develop g-type pattern germination (fine branching hyphae) around spores when dormancy is incompletely broken or under stress conditions, while G-type pattern (runner hyphal growth pattern) occurs in favorable conditions. Hyphal branching from germ tube generated by ABA seems similar to its effect on the arbuscule formation (Herrera-Medina et al., 2007).

As a remark, INT staining data suggested a low spore viability in Ga3 and SHAM treatment and higher after ABA and KCN (5 mM) treatment. However, no formazan production was observed in germinated spores following Ga3 application, while the germinative hypha was still growing (data not shown). This suggests that INT staining could correspond to a reducing power marker in the cell, and might be associated to AOX metabolism and spore dormancy, rather than solely to a vital staining.

Mitochondrial Respiratory Inhibitors Influence Fungal Behavior at Symbiotic Phase

Occurrence of the Arum- and Paris-types are not well understood and corresponds to extremes, which can coexist in a developmental continuum within the same root structure (Smith and Read, 2008). Their formation depends partly on genotypic factors characterizing both partners (Karandashov et al., 2004), partly on environmental factors like phosphate availability (Smith and Read, 2008). In potato roots, both mycorrhizal types and root colonization are commonly influenced by phosphate concentration (McArthur and Knowles, 1992). This is in agreement with our observations since P concentration inhibited mycorrhizal development in a dose-dependent way, and Arum-type structures were occurring at low to medium P concentration (1, 10, and 50 ppm), while Paris-type formation appeared at higher P levels (100 and 300 ppm).

Our data on mycorrhized potato suggest that AOX or AOX-related metabolism is involved in arbuscule/hyphal branching and Arum-type formation, while COX or COX-related metabolism is associated with higher hyphal growth and hyphal-coiled shape (Paris-type) formation. Despite the use of SHAM being controversial because of its possible non-specificity to AOX (Bingham and Stevenson, 1995; Day et al., 1996), our results showed differential and opposite phenotypic patterns in plant and fungal behavior when SHAM and KCN treatments were compared. KCN and ABA are known to stimulate AOX activity (Finkelstein et al., 1998; Choi et al., 2000; Rook et al., 2006; Giraud et al., 2009; Millar et al., 2011; Lynch et al., 2012; Wind et al., 2012). These two molecules promoted both arbuscule intensity and branching, but they caused differential mycorrhizal development (M %), with ABA treated plants yielding a higher M % (with colonization in the primary adventitious root recognized under the experimental conditions even up to the base stem). This could be explained by the fact that COX capacity is not inhibited by ABA unlike KCN. On the other hand, we observed that ABA (Experiment 2) tended to promote the AOX gene transcript levels in non-inoculated potato plantlets, but such response was not clearly identified when using KCN (Experiment 3). It would therefore suggest that the mycorrhizal root colonization, but also transcript regulation of the AOX pathway, are dependent from the functional state on the COX pathway. To summarize, we can deduce that mycorrhizal behavior seems to be linked to the mitochondrial respiratory chain-partitioning environment, probably generated from both partners. As a remark, ethylene is another stress hormone that is able to induce AOX pathway (Simons et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2010; Xu F. et al., 2012), but usually impairs mycorrhizal colonization (using epinastic plant or exogenous application, Zsögön et al., 2008; Fracetto et al., 2013). This phenomenon could be partly explained by the action of cyanide (HCN) produced stoichiometrically (1:1) with ethylene, blocking therefore the COX pathway (Xu F. et al., 2012).

Interpretation of the sporulation rise at 50 ppm P in M plants is challenging, but it seems linked with specific plant metabolism independent of mycorrhizal colonization (M %), as already observed by past studies (Douds and Schenck, 1990), while this last parameter harbored high correlation with P concentration. A particularity is observed at 50 ppm P concentration through the various plant phenotypical parameters studied (plant growth parameters – Supplementary Figure S2; mycorrhizal dependency – Figure 8) and corresponds to the highest value of arbuscule intensity (a %, Supplementary Figure S1) with a predominant Arum-type, concomitant with an up-regulation of RiAOX transcripts (Figure 9) and the highest sporulation (Figure 5).

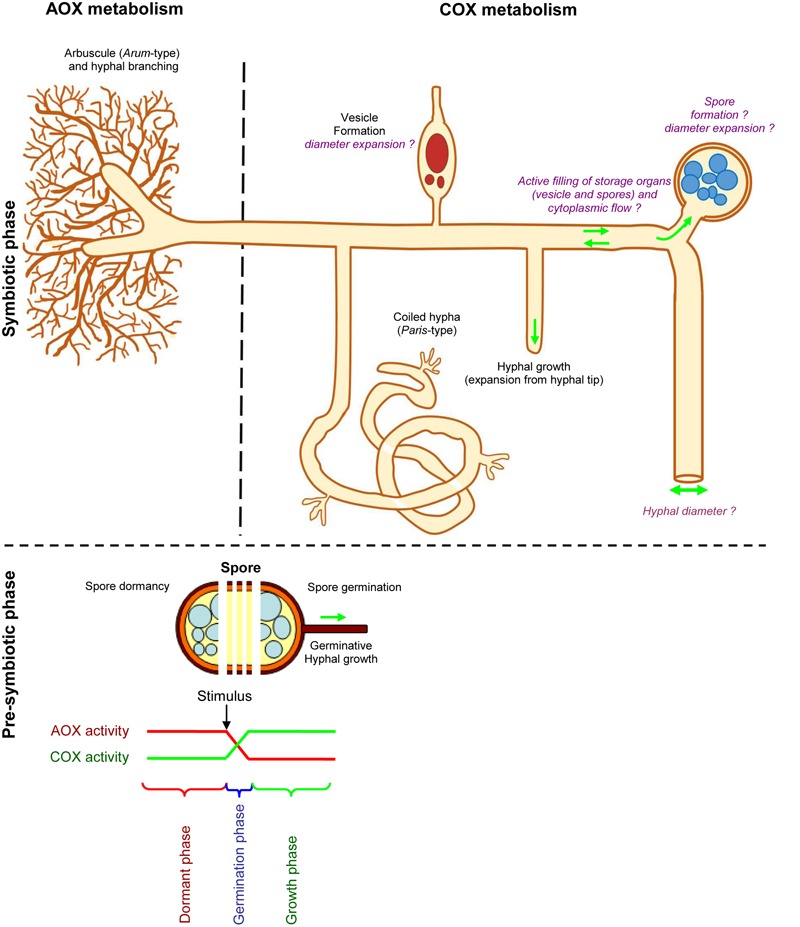

Taking into account all these observations, we propose a scheme defining the roles of AOX and COX in the different mycorrhizal phenotypical behaviors (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Scheme describing potential roles of AOX and COX metabolism in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. This scheme was drawn according to the fungal phenotype observed with SHAM and KCN treatments under in vitro and ex vitro assays. Compared to untreated plants and KCN treatment, SHAM decreases arbuscule intensity within mycorrhizal root fragment (a %), with predominance of Paris–type development, while vesicles intensity remains similar to non-treated plants. Compared to SHAM, KCN plants harbored reduced vesicle within root fragment (v %) and hyphal density (H %), but higher arbuscule formation in mycorrhizal root fragments (a %). Note that the inhibitors response on fungal parameters may differ according to specific P concentration. Spore germination is inhibited by ABA, SHAM, and KCN but enhanced by Ga3. We propose that spore germination corresponds likely to a punctual event involving respiratory shift that transfers a dormant state (likely linked with AOX pathway) to an active state (likely linked with COX pathway) allowing the fungus to explore and reach a host plant root (see text in section, Mitochondrial Respiratory Inhibitors Influence Fungal Behavior at Pre-symbiotic Phase). However, the respiratory chain pathway involved in spore formation and size, hyphal diameter, as well as the filling of storage organs and active cytoplasmic flow in AMF remains unknown. We suggest that COX metabolism might be preferentially expressed in these different processes that require energy (suggestions are written in purple).

Mitochondrial Respiratory Inhibitors Induced Opposite Mycorrhizal Growth Dependency

Although many factors can influence the MGD, it is usually recognized that high P concentrations decrease MGD, which may become negative (Smith and Smith, 2011a). In our study, no correlation was found between MGD and P concentration, but respiratory inhibitors induced opposite responses. All possible MGD responses (neutral for non-treated plants, positive under KCN and negative under SHAM) were observed within the same AMF-plant biosystem, illustrating the high plasticity of mycorrhizal behavior linked to the physiological context. We show the possibility to obtain increasing yield with increasing P concentration when respiration in the plant–AMF system is associated with AOX pathway (i.e., in KCN treatments), occurring with a low fungal colonization and associated with relatively stable and almost maximal positive MGD. This goes together with a predominant Arum-type structures and higher arbuscule intensity when compared to treatments where COX pathway would be engaged (i.e., in SHAM treatments), in which Paris-type structure is predominant and associated with a negative MGD. This is consistent with the study of van Aarle et al. (2005), showing that Arum-type structures had higher metabolic activity than Paris-type ones. Moreover, even if SHAM reduced the MGD and the arbuscule intensity, while favoring Paris-type structures, the AMF produced a denser mycelium (h %) and as many vesicles as in non-treated mycorrhizal plants (except at 1 ppm P). AMF responses on plant performance seem therefore to depend mainly on the ability to form hyphal branching (Arum-type), possibly by an increased exchange surface for providing nutrients to plants (Kobae and Hata, 2010; Bapaume and Reinhardt, 2012). However, if MGD responses seem related with arbuscule type in KCN and SHAM treatments, no direct relationship was found between arbuscule intensity and MGD. This leads to the hypothesis that although various membrane transporters (phosphate, amino acid, sugar or nitrogen) were characterized in arbuscules, these fungal structures might not constitute preferential sites for nutrient/element exchanges, and a role should be also attributed to intraradical hypha. This assumption is supported by the fact that glucose transporters were observed not only in arbuscules but also on intraradical hyphae (Helber et al., 2011).

The mycorrhizal dependency variation has been attributed to plant species and cultivars, fungal species and isolates, host and symbiont interplay, mycorrhizal rate, soil phosphorus concentration and environmental conditions (Plenchette et al., 1983; Singh, 2001; Smith and Smith, 2011a). Our data suggest that the electron flow partitioning, which is modulated by environmental stimuli and genetic background, corresponds to a main metabolic component determining the MGD related to the mycorrhizal type. Finally, AOX metabolism, linked usually with higher ABA content, is known to be related to plant growth regulation and has been reported to be connected to growth depression (Sieger et al., 2005). This may partly explain the negative MGD phenomenon that AMF might trigger during early developmental stages in some plant species (Koide, 1985; Graham and Abbott, 2000; Smith et al., 2009; Ronsheim, 2012) during the implementation of the induced systemic response in the plant (Pozo et al., 2002; Hause and Fester, 2005; Hause et al., 2007).

Mitochondrial Respiratory Inhibitors Influence Symbiotic Nutrient Transport

Arbuscular mycorrhizal inducible Pi transporters of the Pht1 family have been described as markers of mycorrhizal development and, in some cases, proposed as markers of mycorrhizal functionality (Javot et al., 2007). Partly in accordance to this statement, our data show a correlation between AM-inducible transporter expression (StPT3, StPT4, and StPT5) and the mycorrhizal development. A gradual repression of the MPU pathway with increasing P availability in non-treated mycorrhizal plants was also observed, which is in accordance with several previous studies on Solanaceae species (Chen et al., 2007; Nagy et al., 2009), suggesting that the MPU is not functional at high P levels. However, the repression of the MPU by P disappeared when plants were treated with KCN, and surprisingly all AM-inducible P transporters were strongly up-regulated at 300 ppm in non-inoculated plants. This last observation deserves further investigations, as no previous works have been done with very high P concentrations to our knowledge.

The mycorrhizal impact on DPU is less clear. A number of studies have shown that AM colonization of plants down-regulates the expression of the DPU Pi transporters (Rausch et al., 2001; Burleigh et al., 2002; Glassop et al., 2005; Requena, 2005; Nagy et al., 2006), while other studies pointed contrasted transcriptional regulations. Chen et al. (2007) showed a mycorrhiza-induced down-regulation of Pht1;1 and Pht1;2 expression under low-P conditions, but up-regulation of Pht1;2 under high-P conditions for pepper, eggplant and tobacco. In tomato, Nagy et al. (2009) did not find any change in the transcript abundance for SlPT1 and SlPT2 upon root colonization. Our data are in accordance with these latter observations, as presence of AMF did not necessarily induced down-regulation of non-AM-inducible transporters, but responses were specific to P concentrations. For example, it was noticed that AMF induced an up-regulation at 100 ppm P but a down regulation at 10 ppm P for StPT1, while an up-regulation of StPT2/6 was observed at 100 ppm P. Only StPT2/6 was regulated by P availability. KCN treatment induced an up-regulation of DPU transporters in mycorrhizal conditions.

Fungal Pht1 genes are known to be expressed in the intraradical phase (Harrison and van Buuren, 1995; Benedetto et al., 2005; Balestrini et al., 2007; Tisserant et al., 2012; Fiorilli et al., 2013; Walder et al., 2016). Fiorilli et al. (2013) showed a slight down-regulation of RiPT1 when exposed to higher P concentrations, and Walder et al. (2016) reported a positive correlation of RiPT5 transcript levels and Pi acquisition in Sorghum. In our study, only RiPT5 was slightly regulated by P levels, with up-regulation in concentrations higher than 50 ppm in non-treated conditions. Few data exist on the translocation of Pi across the inner mitochondrial membrane by Pht3 family in plants and fungi. In our study, no clear role emerged for these transporters within AMF symbiosis. StMPT3, which presented the highest expression levels in the roots, appeared to be constitutive, and only StMPT1a was slightly up-regulated by the presence of R. irregulare in non-treated conditions. RiMPT appeared also to be constitutively expressed in our experimental conditions.

In plants, several transcriptomic analyses revealed that AM establishment can induce the expression of plant N transporters, mainly in arbusculated cells (Gomez et al., 2009; Guether et al., 2009; Kobae et al., 2010; Gaude et al., 2012; Ruzicka et al., 2012). AMTs identified in tomato LeAMT4 and LeAMT5 were reported to be exclusively expressed in mycorrhizal roots and not regulated by NH4+ (Ruzicka et al., 2012). The two potato homologs, StAMT4 and StAMT5, were strongly up-regulated by AMF, and were gradually repressed by P in mycorrhizal plants. This decrease in transcript levels can be attributed to the reduction of fungal structures inside the roots. However, in the case of AM-inducible AMTs, such as AM-inducible Pht1, NM plants presented a strong up-regulation at a high P level (300 ppm). As for P transporters, a suppression of this up-regulation at 300 ppm P in the presence of KCN was observed and could be explained by the need of a functional COX pathway for ammonium and phosphate transport. NH4+ uptake via AMT seems indeed to be accompanied by H+ extrusion by the plasma membrane H+-ATPases for maintenance of the cytosolic charge balance, and increased fluxes of NH4+ would increase the demand for respiratory ATP (Britto and Kronzucker, 2005). Hachiya et al. (2010) suggested that the ammonium-dependent increase of the O2 uptake rate can be explained by the up-regulation of the cytochrome pathway, which may be related to the ATP consumption by the plasma-membrane H+-ATPases. Similarly, P transport is a proton-dependent process, and the H+-ATPase HA1 of Medicago truncatula was shown as essential for P transport in AM symbiosis (Krajinski et al., 2014). StHA1 is also up-regulated at 300 ppm P in non-inoculated plants compared to 1 ppm P and repressed in mycorrhizal plants. It can be therefore hypothesized that an impaired COX pathway would repress ammonium transport via AMT gene family members.

P and N AM-inducible transporters were found to be connected to the mycorrhizal development in non-treated plants. On the other hand, no correlation was observed between the expression of P and N AM-inducible transporters and the presence of either specific fungal structures (arbuscule or intraradical hypha) or any MGD parameters across the treatments (Supplementary Tables S2–S4). In particular, M KCN plants were associated with positive MGD compared to NM KCN plants but the transcript levels of genes encoding AM-inducible transporters were similar to M SHAM treatments. Several studies showed a lack of relationship between Pht1 gene expression and mycorrhizal Pi acquisition (Grace et al., 2009; Grønlund et al., 2013; Walder et al., 2015). It would therefore indicate that MGD and that plant’s Pi acquisition through the MPU is not quantitatively regulated by the expression level of AM-inducible Pht1 genes. These observations, combined with the lack of repression of the MPU by P in presence of KCN, and the strong up-regulation of AM-inducible P transporter genes at 300 ppm in NMs, suggest that these transporters are not suitable markers for a functional symbiosis in field conditions where high P concentrations can occur and natural or anthropogenic source of cyanides can be found in soil or water (with concentrations as high as 100 mg kg DW-1).

What about the Metabolic Role of AOX and COX in AMF?

Despite sugar transporters being found and characterized (Helber et al., 2011), AMF are still unable to complete their life cycle even when carbon sources are added in in vitro culture systems without the presence of plant roots. Some publications showed even the opposite: glucose and fructose application under axenic or monoxenic conditions resulted in reduced fungal growth or spore germination rate (Mosse, 1959; Koske, 1981; Hepper, 1982; Siquiera and Hubbell, 1986; Wang et al., 2015), while culture media devoid of sucrose can stimulate spore germination, hyphal growth (D’Souza et al., 2013), as well as, sporulation (St-Arnaud et al., 1996). In many publications, the definition of obligate biotrophy of AMF deals with their dependency on plants for carbohydrate supply (mainly glucose and fructose, Pfeffer et al., 1999). But obviously, this statement seems incomplete since it is not yet strictly proven by the successful implementation of an axenic culture. Genomic and transcriptomic data obtained from R. irregulare were not helpful since this fungal species would possess all the necessary genes to harbor saprobe behavior (Tisserant et al., 2012; Tisserant et al., 2013), although no evidence for gene encoding for fungal multi-domain fatty acid synthase was found (Wewer et al., 2014). Therefore, the fungal needs related to the biotrophy of AMF remains still an open question. In this way, it seems important to emphasize that plants provide, at least, a habitat, i.e., a physical growth support associated with a favorable physiological frame allowing uptake and metabolic assimilation of carbon sources that AMF seems not to encounter without host. This questions the definition of the metabolic frame (induced by stress signals) favorable to AMF colonization, arbuscule development and functions on plant performances. We discuss below the role of COX and AOX, which can shed new light that would allow a better understanding and mastering of mycorrhiza.

COX Pathway and Aerobic Respiration

In non-inoculated plants, fresh biomass and potato yield are repressed by KCN and enhanced by SHAM (especially at 100 and 300 ppm P). This suggests that the tuberization is an active COX-dependent process needing O2, which is consistent with the high O2 concentration requirement observed previously for tuber formation (Saini, 1976; Hooker, 1981; Cary, 1985; Geigenberger et al., 2000). This fits also with the reported effect of SHAM, known to optimize the O2 flow through plant tissues (Sesay et al., 1986; Spreen Brouwer et al., 1986; Møller et al., 1988; Gupta et al., 2009). The positive MGD on yield observed in KCN treatment suggests that AMF improve plant respiration, not only related to P concentration, but also to tissue oxygenation, in order to sustain both COX needs and a better carbon allocation in the tuber. However, our expression data obtained at harvest for StCOXVb and StCytc1 genes are difficult to interpret in link with these assertions. StCytc1 expression is up-regulated in NM KCN plants compared to NM SHAM plants at 10 and 100 ppm P, but it remains similar for the other P concentrations tested, suggesting probable other regulation levels related to COX pathway.