Abstract

Introduction

Selecting a suitable wound dressing for patients with partial-thickness burns (PTBs) is important in wound care. However, the comparative effectiveness of different dressings has not been studied. We report the protocol of a network meta-analysis designed to combine direct and indirect evidence of wound dressings in the management of PTB.

Methods and analysis

We will search for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the wound-healing effect of a wound dressing in the management of PTB. Searches will be conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register and CINAHL. A comprehensive search strategy is developed to retrieve articles reporting potentially eligible RCTs. Besides, we will contact the experts in the field and review the conference proceedings to locate non-published studies. The reference lists of articles will be reviewed for any candidate studies. Two independent reviewers will screen titles and abstracts of the candidate articles. All eligible RCTs will be obtained in full text to perform a review. Disagreement on eligibility of an RCT will be solved by group discussion. The information of participants, interventions, comparisons and outcomes from included RCTs will be recorded and summarised. The primary outcome is time to complete wound healing. Secondary outcomes include the proportion of burns completely healed at the end of treatment, change in wound surface area at the end of treatment, incidence of adverse events, etc.

Ethics and dissemination

The result of this review will provide evidence for the comparative effectiveness of different wound dressings in the management of PTB. It will also facilitate decision-making in choosing a suitable wound dressing. We will disseminate the review through a peer-review journal and conference abstracts or posters.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO CRD42016041574; Pre-results.

Keywords: partial-thickness burns, wound dressing, systematic review protocol, network meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The comparative effectiveness of different wound dressings in the management of partial-thickness burn has not been studied; our network meta-analysis will be the first to answer the question.

We will conduct this network meta-analysis in a Bayesian framework and test robustness of the result with multiple meta-regressions and sensitivity analyses.

We will include trials assessing the effectiveness of traditional wound dressings that were treated as standard wound care. These trials are usually published before the year 2000, the quality of which may be generally low.

Introduction

Partial-thickness burns (PTBs) are burn wounds commonly seen in emergency rooms. PTBs are characterised as blister, swelling and redness on the skin. These skin damages affect the epidermis and structures beneath the epidermis such as blood vessels, hair follicles and nerves.1 PTB is usually categorised as superficial PTB or deep PTB. Superficial PTBs involve damage to the papillary dermis, characterised as intact blisters, moderate oedema, a moist surface under the blisters, a bright pink or red colour. Deep PTBs involve damage to both the papillary and reticular dermis, characterised as broken blisters, substantial oedema, a wet surface, waxy white colour.2 The difference between superficial and deep PTB is whether the burns extend through all skin layers, and deep PTBs do. In the USA alone, there are 486 000 burn injuries (43% caused by fire or flame, 34% by scald, 9% by contact, 4% by electrical burns, 3% by chemical burns and 7% by other reasons) each year.3 More than 60% of the acute hospitalisations are caused by burn injuries.4 Patients suffer pain, scars and mood disturbances like distress, anxiety or depression from PTB. Healthcare costs for burns are high; a median cost of $44 024 is needed for one patient.5 Although direct data on cost for PTB are not available, they were assumed to be costly.6 Therefore, efficient and effective wound care for PTB management is urgently needed.

PTB management consists of wound preparation, wound cover and postwound care.7 Wound dressings, covering the wound to accelerate wound healing and protect the wound from infection, include modern dressings like hydrocolloids, hydrofibre, silicones, alginates and polyurethane and traditional dressings like paraffin gauze and silver sulfadiazine (SSD).

In the wound dressings, modern dressings are reported to achieve better burn healing than traditional dressings like silver SSD, although quality of the overall evidence is low.8 Additionally, the relative efficacy and toxicity of modern dressings have not been studied. Silver SSD, one of the traditional dressings, has been reported as the gold standard for PTB management.9 However, SSD is under criticism for causing wounds to dry up and not supporting optimal healing.10 Unlike SSD, modern dressings have the advantages of keeping a moist environment around burn wounds and effectively protecting the wound from exposure to pathogenic bacterium.8 Each of these modern dressings has its own features in achieving optimal healing. For example, hydrocolloids, one of the modern dressings, contain gelatin, pectin and sodium carboxymethylcellulose in an adhesive polymer matrix. When the polymer matrix of the hydrocolloid dressings contacting wound exudate would form a gel, so they facilitate autolytic debridement of wounds.11 Polyurethane films are adhesive-coated sheets applied directly to burn wounds. The advantage of polyurethane lies in that it is permeable to water vapour, oxygen and carbon dioxide but not to water or pathogenic bacterium. However, polyurethane is not suitable for wounds with heavy exudate.12 The other modern dressings have their own advantages, which leave the physicians and patient with a selection dilemma.

The goal of burn management is to achieve rapid wound healing, pain relief, rehabilitation with minimal scars and optimal functional ability. Therefore, questions are raised: Which are the best wound dressings in achieving rapid healing, in relieving pain, in retaining optimal functional ability or in leaving minimal scars? To answer these questions, we need results from pairwise comparisons of different wound dressings, so a network meta-analysis is warranted. The network meta-analysis combines direct (head-to-head comparisons of different dressings) and indirect (we could simulate dressing A vs B if they share the same comparator C) evidence.13 The analysis is usually done with the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method, since it has multiple advantages, such as producing results for all comparisons of interest within a connected network, calculating the probability that each drug is the best treatment and adjusting for correlations within multiarm trials.14 In summary, we will perform a Bayesian network meta-analysis to study the comparative effectiveness of different wound dressings in the management of PTB, providing a reference basis for decision-making.

Methods

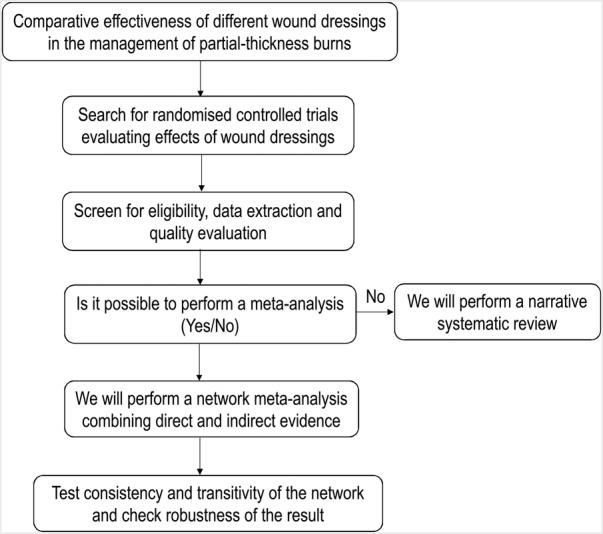

This systematic review and network meta-analysis has been registered (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, reference number: CRD42016041574). Figure 1 gives an overview of the study process. It is anticipated to be finished in December 2016. The review is financially supported by the Key Program of National Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction of China and the Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program of Fujian. It is also sponsored by the Science and Technology Key Project of Fujian Province, China (reference number: 2014y0056). This study is designed and reported according to the standards of quality for reporting systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P).15

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

We will search for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of a wound dressing for wound healing in patients with PTB, since RCTs are recognised as the gold standard in evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention. We will include RCTs comparing wound dressings with no intervention, placebo dressings or other wound dressings (treated as standard wound cover). RCTs with a cross-over design will be excluded, since PTB has rapid evolution (superficial PTBs usually heal within 2 weeks16).

Types of participants

Patients who have burns classified as PTB (including superficial and deep PTB) will be included in this review. According to the guideline for management of PTBs,7 patients with burns that are wet, painful, blistering, red, white or pink will be included. Patients with burns that are dry, painless, grey, white or brownish will be excluded, for these burns may be full-thickness burns. We will also include patients with burns classified as grade II burns, which used to be another name of PTB.17 We will include both paediatric and adult patients who receive treatments in primary, secondary or tertiary care settings. Patients who need referral to wound-care specialists will be excluded, since using wound dressings alone plays a little role in the treatments for these patients. Additionally, we will include patients with fresh PTBs (within 72 hours after injury), since PTBs beyond 72 hours may be infected and thus need special wound care in addition to wound dressings. Adolescents (age under 18 years) or elders (aged over 65 years) with the size of the burn area surpassing 10% of the total body surface area (TBSA) or adults (aged between 18 and 65 years) with the size surpassing 15% of TBSA will be excluded, since these patients also need special wound care managed by specialists.7 18 19 Patients with burns caused by electric or chemistry or with burns located on the face, neck, hands, feet, armpits, popliteal region or genitals will be excluded, since these burns need special wound care in addition to local wound dressings.7 20 21 Concomitant diseases in the endocrine and immune systems (eg, diabetes) should be reported in RCTs recruiting patients aged over 50 years; otherwise, these RCTs will be excluded. Diseases in these two systems will influence time to heal PTB.22

Types of interventions

Both traditional and modern wound dressings will be assessed in this review. Traditional wound dressings refer to paraffin gauze and silver SSD, which are used less often now, because they may cause wounds to dry up and lead to increased risk of infection.7 9 23 However, since they have been conventionally used as standard wound care in the past 30 years,24 we will include them as reference comparators. Modern wound dressings, such as hydrocolloid, hydrogel, hydrofibre, silicones, bioengineered skin substitutes, alginates and polyurethane, will be included for assessment. These modern dressings, compared with traditional dressings, have several advantages of keeping a moist wound environment to facilitate healing, providing an effective barrier to reduce the risk of infection and maintaining maximum contact with the wound to relieve pain.25 Additionally, they are easy to use and remove, which guarantees a minimal extent of pain during attaching or removing dressings. Duration of wound dressings or frequency of changing wound dressings will not be limited.

Types of outcomes

We will include RCTs evaluating the effects of wound dressings with the following outcomes: time to complete wound healing, proportion of wounds achieving complete closure at the end of treatment (3–4 weeks), change in wound surface area at the end of treatment (3–4 weeks), patient's satisfaction with the attachment and removal of dressings, proportion of patients needing burn care from specialists or surgery, or incidence of adverse events.

Search methods

We will electronically search in the following database: Ovid MEDLINE (from 1966 to 2016), EMBASE (from 1980 to 2016), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (from inception to 2016), the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (from inception to 2016) and EBSCO CINAHL (from 1980 to 2016). A comprehensive search strategy has been developed (table 1). We will also search clinicaltrials.gov for RCTs that were registered but not reported (from inception to 2016), and we will contact the sponsors or principal investigators of these trials to ask for data. Besides, we will contact the experts in the field and review the conference proceedings to locate non-published studies. The reference lists of articles will be reviewed for any candidate studies.

Table 1.

Search strategy for MEDLINE (via OVID)

| N | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | randomized controlled trial.pt |

| 2 | controlled clinical trial.pt |

| 3 | randomized.ab |

| 4 | placebo.ab |

| 5 | randomly.ab |

| 6 | trial.ab |

| 7 | groups.ab |

| 8 | or/1–7 |

| 9 | exp animals/not humans.sh |

| 10 | 8 not 9 |

| 11 | exp Bandages, Hydrocolloid |

| 12 | (hydrocolloid$ or hydrofibre or hydrofiber).tw |

| 13 | exp alginate-polyethylene glycol acrylate |

| 14 | (alginate$ or seasorb or sorbalgon or sorbsan or tegagen).tw |

| 15 | exp Hydrogel |

| 16 | (hydrogel$ or hydrosorb or novogel or purilon or sterigel).tw |

| 17 | exp occlusive dressings |

| 18 | foam dressing$.tw |

| 19 | (retention tape or hypafix).tw |

| 20 | (paraffin gauze).tw |

| 21 | (biosynthetic substitute$).tw |

| 22 | (antimicrobial dressing$ or acticoat).tw |

| 23 | or/11–22 |

| 24 | exp burns |

| 25 | (burn or burns or burned).tw |

| 26 | (partial thickness burn$).tw |

| 27 | or/24–26 |

| 28 | 10 and 23 and 27 |

Identification of studies

Two reviewers (QJ and S-BW) will independently screen titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles for eligible RCTs. If it is impossible to determine the eligibility of the eligible RCTs through titles and abstracts, we will obtain full-text copies for further evaluation. Disagreement on eligibility of a RCT will be solved by group discussion and arbitrated by a third reviewer (X-DC).

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias of included RCTs will be assessed with the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. We will use this assessment tool to determine internal validity of the RCTs in six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues. In assessing other issues, we will focus on baseline imbalance and source of financial support. The baseline imbalance may cause overestimation or underestimation of an experimental intervention.26 Receiving financial support from a commercial company that produces and provides active wound dressings may cause overestimation of the effect of this wound dressing. Each of the six domains will be classified as low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias. Details for this classification are described in the Cochrane handbook.27 Any discrepancy in the risk of bias assessment will be resolved by group discussion and arbitrated by a third reviewer (X-DC). The overall strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE).28

Data extraction

Standardised extraction forms will be developed to record the following information: study characteristics (first author, publication year, study sites, number of participants, open label/single blind/double blind, study duration, source of financial support), patient's characteristics (age, gender, diabetes (yes/no), wound infected (yes/no), TBSA, body mass index, cause of burn, duration of burn, burn depth), interventions and comparisons (name of experimental or control interventions, duration of treatment, frequency of wound changes, special wound care (yes/no), healthcare facilities where the participants receive wound dressings (primary/secondary/tertiary care)) and outcomes (definition of an outcome, intention-to-treat analysis (yes/no), main results and variables for calculating effect size). Extracted data will be entered into an electronic system developed with the EpiData EntryClient (V.2.0.7.22). To lower the risk of entry error, double data entry and cross-check will be performed in the system.

Statistical analysis

We will summarise characteristics of the included RCTs and present direct and indirect comparisons between different wound dressings. We will check clinical heterogeneity in the included RCTs through tables and visual plots. Examination of the clinical heterogeneity will focus on patients' baseline characteristics, healthcare facilities where patients receive wound dressings and duration of follow-up. Statistical heterogeneity will also be investigated with the I2 statistics. Different wound dressings will first be categorised as different classes like hydrocolloid, hydrogel, silicones, etc. We will test the agreement in effect size in a specific class, using the I2 value of 50% as a cut-off point. I2>50% indicates significant heterogeneity in the RCTs testing one of the wound dressing classes. We will second test the heterogeneity in individual wound dressings when possible. If the included RCTs show clinically or statistically significant heterogeneity, we will give a narrative review. Otherwise, we will proceed to a traditional meta-analysis, calculating the effect size of different classes of wound dressings compared with placebo or active controls. For continuous outcomes, standardised mean difference (SMD) will be calculated; for dichotomous outcomes, ORs will be computed. We will synthesise SMD or OR with the DerSimonian-Laird method (random-effects model).

A Bayesian network meta-analysis will be performed to combine direct and indirect evidence. In this network meta-analysis, measures of relative effect sizes will be ORs in the dichotomous outcomes and SMDs in the continuous outcomes. Both ORs and SMDs will be reported with their 95% credible intervals (95% CI). The 95% CI could be elucidated as a 95% probability that the true OR or SMD falls in the reported range. The network meta-analysis will be performed with a random-effect model using WinBUGS 1.43 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge University, UK). Each analysis will be based on non-informative priors for calculation of effect sizes and 95% CI. We will use the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) to rank the wound dressing classes. The SUCRA presented as percentages compare each wound dressing with an intervention presumed as the best treatment without uncertainty, so a larger SUCRA means a more effective wound dressing class. Transitivity and consistency are the two key elements representing the credibility of a network meta-analysis. The assumption of transitivity is that the distribution of effect modifiers is not different in each pairwise comparison in the network. To account for transitivity in the network, we will assess participant's characteristics (infected or non-infected wounds, patients with or without diabetes, smoker or non-smoker, with or without long-term use of steroids), study designs (duration of follow-up and risk of bias) and interventions (duration of treatment and wound dressings given in primary or secondary or tertiary care). Consistency between direct and indirect comparisons will be assessed. The result of direct comparisons will be acquired through the aforementioned traditional meta-analysis, whereas the result of indirect comparisons will be obtained through excluding those studies with head-to-head comparisons. The consistency will be evaluated with the I2 statistics, with an I2<25% indicating mild inconsistency, an I2 between 25% and 50% showing moderate inconsistency, and an I2>50% representing severe inconsistency. Given the feature of Bayesian statistical analysis, p values will not be estimated and reported for each comparison.

Several sensitivity analyses will be performed on the primary outcome to investigate the reasons for potential heterogeneity. The analyses include exclusion of: trials with a high risk of bias (assessed by the Cochrane risk of bias tool); trials including patients with diabetes (patients with diabetes present with a longer time to wound healing); trials including smokers; trials including patients with long-term use of steroids; trials comparing different usages of the same wound dressings (usages that are different in frequency of changing dressings or ingredients); trials with missing SD or 95% CI; trials that are not analysed on an intention-to-treat basis; trials with negative findings (in which the experimental wound dressings or active comparators are not superior to placebo controls).

Multiple meta-regressions will be performed to study the impact of sponsorship (whether the sponsors are involved with manufacture of experimental wound dressings or active comparators); mean age of the included participants (ageing leads to delayed epithelialisation, so elders may need longer healing time than adolescents); subtypes of PTB (superficial or deep PTB; patients with deep PTB may theoretically need a longer time in wound healing than those with superficial PTB), blinding method (open label, single blind, double blind), risk of bias (high, unclear, low), TBSA and duration of PTB. If a significant impact of these factors is found, we will perform subgroup analyses according to these factors.

Dealing with the missing data

We will contact authors who reported trials with missing data to ask for original data. If the original data are not available, we will try to calculate the missing data through other variables given in the articles. For example, we will estimate SD through 95% CI or SE.

Discussion

This network meta-analysis will summarise the direct and indirect evidence aiming to provide a ranking of the conservative treatment for PTB. The results of this network meta-analysis may help the patients with PTB and their physicians select the best option. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first network meta-analysis conducted to determine the optimal conservative treatment for PTB. This study protocol is designed to meet the PRISMA-P standards.15 It is designed without knowing the study data or results from the existing published literature. The results of this meta-analysis will help the decision-makers come to their own conclusions regarding which is the best wound dressing for patients with PTB.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the key Program of National Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction of China and key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program of Fujian, China and also sponsored by the science and technology key project of Fujian Province, China (NO: 2014Y0056).

Footnotes

Contributors: X-DC contributed to the conception and design of the study protocol. The search strategy was developed by Z-HC. QJ and S-BW will screen the title and abstract of retrieved studies and extract data from included trials. X-DC will check the accuracy and completeness of data entry. Z-HC will synthesise and analyse the extracted data. All authors drafted this protocol and approved it for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: If this systematic review has results, the authors would like to share the original data with the public.

References

- 1.Klasen HJ. A historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. II. Renewed interest for silver. Burns 2000;26:131–8. 10.1016/S0305-4179(99)00116-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hettiaratchy S, Papini R. Initial management of a major burn: II—assessment and resuscitation. BMJ 2004;329:101–3. 10.1136/bmj.329.7457.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Burn A. Burn incidence and treatment in the United States: 2015. Chicago: American Burn Association, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association AB. Burn incidence and treatment in the United States: 2013 fact sheet 2013. http://www ameriburn org/resources_factsheet php 2015

- 5.Hop MJ, Polinder S, van der Vlies CH et al. Costs of burn care: a systematic review. Wound Repair Regen 2014;22:436–50. 10.1111/wrr.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goei H, Hop MJ, van der Vlies CH et al. Return to work after specialised burn care: a two-year prospective follow-up study of the prevalence, predictors and related costs. Injury 2016;47:1975–82. 10.1016/j.injury.2016.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alsbjörn B, Gilbert P, Hartmann B et al. Guidelines for the management of partial-thickness burns in a general hospital or community setting—recommendations of a European working party. Burns 2007;33:155–60. 10.1016/j.burns.2006.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasiak J, Cleland H, Campbell F et al. Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(3):CD002106 10.1002/14651858.CD002106.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atiyeh BS, Costagliola M, Hayek SN et al. Effect of silver on burn wound infection control and healing: review of the literature. Burns 2007;33:139–48. 10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoogewerf CJ, Van Baar ME, Hop MJ et al. Topical treatment for facial burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD008058 10.1002/14651858.CD008058.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas S. Hydrocolloid dressings in the management of acute wounds: a review of the literature. Int Wound J 2008;5:602–13. 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00541.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boateng JS, Matthews KH, Stevens HN et al. Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: a review. J Pharm Sci 2008;97:2892–923. 10.1002/jps.21210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2002;21:2313–24. 10.1002/sim.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ et al. NICE DSU technical support document 2: a generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmauss D, Rezaeian F, Finck T et al. Treatment of secondary burn wound progression in contact burns—a systematic review of experimental approaches. J Burn Care Res 2015;36:e176–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearns RD, Holmes JH, Cairns BA. Burn injury: what's in a name? Labels used for burn injury classification: a review of the data from 2000–2012. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 2013;26:115–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travis TE, Moffatt LT, Jordan MH et al. Factors impacting the likelihood of death in patients with small TBSA burns. J Burn Care Res 2015;36:203–12. 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson PC, Hardwicke J, Bamford A et al. Revised estimates of mortality from the Birmingham Burn Centre, 2001–2010: a continuing analysis over 65 years. Ann Surg 2014;259:979–84. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829160ca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alemayehu H, Tarkowski A, Dehmer JJ et al. Management of electrical and chemical burns in children. J Surg Res 2014;190:210–13. 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornhaber R, Wilson A, Abu-Qamar MZ et al. Adult burn survivors’ personal experiences of rehabilitation: an integrative review. Burns 2014;40:17–29. 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barsun A, Sen S, Palmieri TL et al. A ten-year review of lower extremity burns in diabetics: small burns that lead to major problems. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:255–60. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318257d85b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermeulen H, Westerbos SJ, Ubbink DT. Benefit and harm of iodine in wound care: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2010;76:191–9. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marone P, Monzillo V, Perversi L et al. Comparative in vitro activity of silver sulfadiazine, alone and in combination with cerium nitrate, against staphylococci and gram-negative bacteria. J Chemother 1998;10:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Queen D, Orsted H, Sanada H et al. A dressing history. Int Wound J 2004;1:59–77. 10.1111/j.1742-4801.2004.0009.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts C, Torgerson DJ. Understanding controlled trials: Baseline imbalance in randomised controlled trials. BMJ 1999;319:185 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1. 0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490–4. 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]