Abstract

Introduction

Hospitals conduct extensive screening procedures to assess colonisation of the body surface of neonates by gram-negative bacteria to avoid complications like late-onset sepsis. However, the benefits of these procedures are controversially discussed. Until now, no systematic review has investigated the value of routine screening for colonisation by gram-negative bacteria in neonates for late-onset sepsis prediction.

Methods and analysis

We will conduct a systematic review, considering studies of any design that include infants up to an age of 12 months. We will search MEDLINE and EMBASE (inception to 2016), reference lists and grey literature. Screening of titles, abstracts and full texts will be conducted by two independent reviewers. We will extract data on study characteristics and study results. Risk of bias will be assessed using Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) and Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tools. Subgroup analyses are planned according to characteristics of studies, participants, index tests and outcome. For quantitative data synthesis on prognostic accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of screening to detect late-onset sepsis will be calculated. If sufficient data are available, we will calculate summary estimates using hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristics and bivariate models. Applying a risk factor approach, pooled summary estimates will be calculated as relative risk or OR, using fixed-effects and random-effects models. I-squared will be used to assess heterogeneity. All calculations will be performed in Stata V14.1 (College Station, Texas, USA). The results will be used to calculate positive and negative predictive value and number needed to be screened to prevent one case of sepsis. Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) will be used to assess certainty in the evidence. The protocol follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guideline.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will not require ethical approval since it is not carried out in humans. The systematic review will be published in an open-access peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

CRD42016036664.

Keywords: Systematic review, Protocol, Prognostic accuracy, neonatal sepsis, screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review will provide a comprehensive overview on the available evidence regarding the value of routine screening for colonisation by gram-negative bacteria in neonates for late-onset sepsis prediction.

Subgroup analysis will allow investigating the particular role of setting, birth characteristics, sampling strategy and cointerventions for test performance and predictive values

Limitations of the systematic review will arise from the limitations of the included studies, particularly regarding consideration and reporting of confounders in the publications.

Introduction

Epidemiological and clinical background

At neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), late-onset sepsis due to gram-negative pathogens is an important cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality.1 The majority of sepsis episodes (>80%) occurs in preterm neonates.2 Depending on individual factors, setting and species of bacteria, between 11% and 46% of very low birth weight infants (VLBW; <1500 g) are affected.3 Susceptibility to infection is strongly associated with low gestational age and low birth weight.4 5

Already in the 1970s, data were published indicating that infants at NICUs colonised with gram-negative bacteria were at increased risk of developing infections subsequently.6 Consecutively, a number of studies investigated the value of routine surface cultures for the prediction of sepsis.7–10 Some hospitals conduct extensive and costly screening procedures to assess the colonisation of non-sterile locations of the body surface of neonates by gram-negative bacteria to avoid complications like sepsis. In Germany, routine screening for a selection of pathogens is recommended by the German Committee on Hospital Infections and Hygiene (KRINKO). However, the benefits of these screening procedures are controversially discussed. Moreover, since microbiological screening is introduced as part of a bundle of measures (eg, isolation, enhanced barrier nursing), it is often challenging to measure the particular effect of screening. Until now, no systematic review has been published that has investigated the prognostic value of routine screening for colonisation by gram-negative bacteria in this at-risk group for the prediction of late-onset sepsis. Here, we present and explain the protocol for a respective systematic review that will be conducted as part of the piloting phase of the Project on a Framework for Rating Evidence in Public Health (PRECEPT).11

Prognostic/diagnostic test accuracy and risk factors

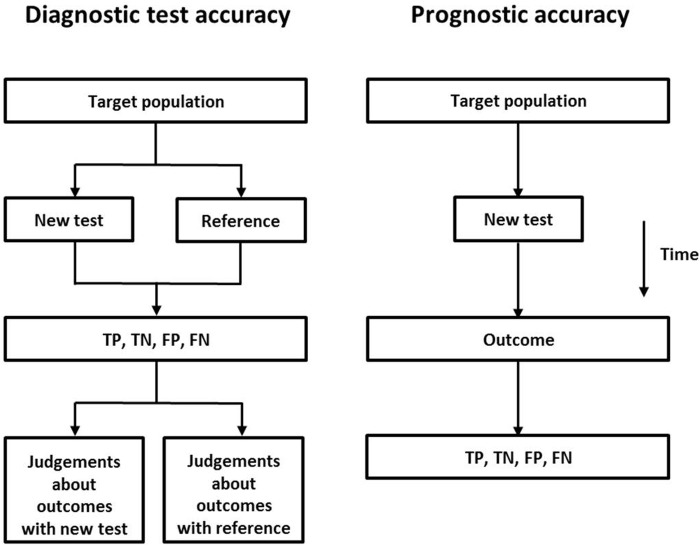

According to the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies, prognostic accuracy studies are using test information to identify patients who will develop an outcome later on (see http://methods.cochrane.org/sdt/handbook-dta-reviews). In this sense, studies that are using screening for gram-negative bacteria to predict sepsis are prognostic accuracy studies. In such studies, the result of a test is compared with the (clinical) outcome. This differs from the approach of diagnostic test accuracy studies where the test result is compared with the result of a reference or ‘gold standard’ test (figure 1). Therefore, prognostic accuracy is not a surrogate for patient-important outcomes, as in diagnostic test accuracy studies.12 This approach has consequences for the design of the studies to be considered. In contrast to diagnostic test accuracy studies where cross-sectional study designs are common practice, cohort studies (prospective or retrospective) are needed to obtain measures of prognostic accuracy.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic versus prognostic test accuracy.

A complementary approach to the analysis of the same data is to conceptualise a positive screening test as the presence of a risk (or prognostic) factor and to calculate the relative risk of developing the outcome. However, it is important to consider that the presence of a high risk ratio (or OR), which is often used to identify prognostic factors for a certain outcome, does not indicate that the respective risk factor performs well in predicting this outcome.13–15 Ware showed that a risk factor strongly associated with a hypothetical outcome (OR 3.58) might have a sensitivity as low as 13% for predicting this outcome. Using the same data, he demonstrated that an OR of 228 would be needed to reach a sensitivity of 80%.15 Therefore, it may not be concluded that a risk factor which is strongly associated with the outcome provides a basis for an effective preventive measure.

Concepts for systematic reviews of prognostic studies

Various approaches exist regarding the systematic assessment and data synthesis of prognostic studies.16 During recent years, it has become more and more accepted that systematic reviews in this field should focus on measures of association between the predictive/prognostic factor and the outcome, such as risk ratio, OR or HR, as well as comprise measures of prognostic accuracy like sensitivity and specificity (eg, see17). Liu et al18 proposed to distinguish between systematic reviews of screening tests and those of diagnostic and prognostic studies. For screening and diagnosis, they suggested assessing sensitivity and specificity, whereas for questions related to prognosis the use of HRs was proposed. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) suggests using a particular framework for systematic reviews of a prognostic test.19 In that paper, Rector et al conclude that it may be informative to assess the accuracy of a prognostic test by calculating sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. However, these authors emphasise that it is critical to consider the time interval between the test and the occurrence of the outcome.19 In our own systematic review, we will compute measures of prognostic accuracy and measures of relative risk and compare the results of these calculations to each other.

Risk of bias

Given the particularities of systematic reviews of prognostic accuracy studies, the question arises whether an established risk-of-bias tool exists that captures common sources of bias in this study design. A number of authors applied tools that were originally designed to address risk of bias in diagnostic test accuracy studies.17 20 21 Currently, the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool is the most advanced and widely used tool for the assessment of risk of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies.22 QUADAS-2 comprises four domains: patient selection, index test, references standard and flow and timing. In each domain, questions related to risk of bias and concerns regarding applicability are included.

However, as explained above, there are apparent differences in study design between diagnostic and prognostic accuracy studies. At least two sources of bias can be identified which are important in prognostic accuracy studies but are not relevant in diagnostic accuracy studies:

Attrition bias: Owing to the prospective character of the study design, loss to follow-up of study participants in the time interval between the conduct of the screening test and the detection of the outcome might create attrition bias. Depending on whether or not rates of loss to follow-up differ between participants with positive and negative screening test results (differential vs non-differential loss to follow-up), sensitivity and specificity will change in point estimate or CI.

Confounding: Confounding will occur if interventions are delivered to study participants depending on the result of the screening test. This may influence the probability of developing the outcome. Again, estimates of sensitivity and specificity might be affected.

Theoretically, it is possible that domain four of the QUADAS-2 tool (‘flow and timing’) sufficiently captures attrition bias as well as confounding in the time interval between screening test and outcome assessment. If this appears not to be the case, we may test whether the additional application of a risk of bias tool for risk factor/prognostic studies such as the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool23 is of additional value.

General objective

To assess the usefulness and value of routine screening for colonisation by gram-negative bacteria performed in NICUs as predictive measures for late-onset sepsis.

Research question

This systematic review will focus on the following primary research questions:

What is the prognostic value (in terms of sensitivity and specificity) of routine screening for colonisation by gram-negative bacteria in neonates at intensive care units for the prediction of late-onset sepsis?

Is colonisation by gram-negative bacteria in neonates at intensive care units a risk factor for later development of late-onset sepsis?

Methods

This systematic review protocol follows the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guideline.24 A copy of the completed PRISMA-P checklist is attached to this protocol (see online supplementary appendix 1). This systematic review is registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Reg. No. CRD42016036664).

bmjopen-2016-014986supp_appendix.pdf (234.7KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Study designs

Studies of any design will be considered. No restrictions will be made regarding publication language or publication status.

Participants

Studies that include infants up to an age of 12 months who are still in a NICU will be considered, irrespective of the gestational age, birth weight and geographical region where the study has been conducted.

Study setting

Studies that were performed in NICUs will be considered.

Search strategy

Database search

We will search MEDLINE and EMBASE from inception to 2016, using the DIMDI (Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information) platform. The planned search strategy is shown in box 1.

Box 1. Search strategy of the systematic review.

#1 neonat*

#2 newborn*

#3 infant*

#4 colonisation

#5 ‘mucosal site*’

#6 ‘mucosal sample*’

#7 ‘mucosal culture*’

#8 ‘superficial culture*’

#9 ‘surveillance culture*’

#10 aspirate

#11 ‘predictive value’

#12 sensitivity

#13 specificity

#14 sepsis

#15 ‘body fluid*’

#16 ‘systemic inflammatory response syndrome’

#17 ‘routine culture’

#18 ‘skin culture’

#19 ‘surface culture’

#20 ‘bacterial colonisation’

#21 ‘microbiological screening’

#22 swab*

#23 #1 OR #2 OR #3

#24 #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22

#25#14 OR #15 OR #16

#26 #23 AND #24 AND #25

Reference lists

These searches will be supplemented by ‘snowballing’, that is, searching for additional studies in the reference lists of identified original studies and reviews.

Grey literature

We will search for grey literature using the Grey Matters Light checklist of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) (http://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters-practical-search-tool-evidence-base-medicine).

Study selection

The study selection process will involve the following steps:

Screening of titles and abstracts.

Screening of full texts.

At both steps, screening will be conducted by two independent reviewers. Potential disagreement will be resolved by discussion or by involving a third reviewer. We will construct a flow chart to document the selection process. A list of excluded studies will be prepared, along with reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

From the included studies, we will extract data on study characteristics and study results. We will construct a data extraction form and pilot test it prior to the start of the review process. Microsoft Office Excel will be used to construct specific extraction forms. One researcher will perform data extraction while a second researcher will independently check for accuracy and details. The following data will be extracted from the original studies:

- General study characteristics:

- complete reference of the study (author, year of publication, title, journal, citation details)

- date of study

- place

- setting (hospital, department, unit, ward)

- study design

- funding source

- Patient/population characteristics:

- inclusion criteria

- exclusion criteria

- gestational age at birth

- birth weight

- age at screening

- sex

- ethnicity

- length of follow-up (time interval between index test and outcome assessment)

- comorbidities

- central line use

- need for surgery

- Index test characteristics:

- description of sampling device

- sampling time point(s)

- sampling location(s) (eg, umbilicus, tracheal, rectal, etc)

- sampling intervals (if repetitive)

- processing of specimen

- detected bacteria (species, characterisation)

- Outcome:

- definition of sepsis

- detected bacteria (species, characterisation)

- (Co)-interventions

- antibiotic use

- isolation

- hand hygiene

- Prognostic accuracy measures:

- true positives

- true negatives

- false positives

- false negatives

- Measures of association (risk factor approach):

- unadjusted relative risk (or OR)

- adjusted relative risk (or OR)

- confounders considered in adjusted analysis.

Risk of bias assessment

Following the guidance of the PRECEPT framework,11 25 we will use the QUADAS-2 tool to assess risk of bias in the included individual studies which report measures of prognostic accuracy.22 Table 1 shows the main components of the tool. The results of the risk of bias assessment will be documented in a separate table for each study alongside the items of QUADAS-2. For studies reporting on prognostic measures in terms of a risk factor (or prognostic study), we will use the QUIPS tool.23 We will construct bar charts as suggested by Van't Hooft et al21 to report summary results of the risk of bias assessments.

Table 1.

Structure of the QUADAS-2 tool22

| Domain | Risk of bias | Concerns regarding applicability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Patient selection | Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes/no/unclear | Is there concern that the included patients do not match the review question? | Concern: low/high/unclear |

| Was a case–control design avoided? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | Risk: low/high/unclear | |||

| 2. Index test(s) | Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes/no/unclear | Is there concern that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differs from the review question? | Concern: low/high/unclear |

| If a threshold was used, was it prespecified? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test results have introduced bias? | Risk: low/high/unclear | |||

| 3. Reference standard* | Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes/no/unclear | Is there concern that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? | Concern: low/high/unclear |

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Risk: low/high/unclear | |||

| 4. Flow and timing | Was there an appropriate interval between the index test and reference standard? | Yes/no/unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive a reference standard? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes/no/unclear | |||

| Could the patient flow have introduced bias? | Risk: low/high/unclear |

*Here equivalent to outcome.

Subgroup analyses

We will extract detailed information on study participants, definitions and settings to enable stratified analysis. In particular, we aim at stratifying the results of the systematic review and meta-analysis, respectively, according to the following variables:

- General study characteristics:

- geographic region (Europe vs North America, etc)

- developed country versus developing country

- study period (<1970, 1971–1980, 1981–1990, 1991–2000, 2001–2010, >2010)

- Patient/population characteristics:

- gestational age (<37 weeks vs ≥37 weeks; <32 weeks vs ≥32 weeks; <26 weeks vs >26 weeks)

- birth weight (<1000 g vs ≥1000 g; <1500 g vs ≥1500 g; <2500 g vs ≥ 2500 g)

- length of follow-up (time interval between index test and outcome assessment)

- Index test characteristics:

- sampling time point(s)

- sampling location(s) (umbilicus vs tracheal, etc)

- species: single species; groups (multidrug-resistant; difficult to treat)

- Outcome characteristics:

- different definitions of sepsis

- Study setting

- clinical routine

- study

- outbreak investigation

- type of ward

Study design.

Statistical analysis

Prognostic accuracy approach: For quantitative data synthesis on prognostic accuracy, we will construct 2×2 tables to calculate sensitivity and specificity for each included study. If sufficient comparable data from more than one study are available, we will perform meta-analysis. To account for the correlation between sensitivity and specificity, we will calculate summary estimates using hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristics models26 as well as bivariate models.27 Results will be displayed graphically using summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plots. We will investigate sources of heterogeneity, using subgroup analysis.

Risk factor approach: For quantitative data synthesis using the risk factor approach, pooled summary estimates will be calculated as relative risk or OR with 95% CIs, using fixed-effects and random-effects models. I-squared will be used to assess heterogeneity. If ≥10 studies per outcome are available, publication bias will be assessed by inspection of funnel plots and applying Begg's and Egger's test.

All calculations will be performed in STATA. The results of the meta-analysis will be used to calculate positive predictive value, negative predictive value and number needed to be screened to prevent one case of sepsis.

Certainty in the evidence (GRADE)

We will use two complementary approaches to assess the certainty in the evidence (formerly: quality of the evidence) according to the methodology suggested by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group.

Prognostic accuracy approach: We will adopt the GRADE approach to diagnostic accuracy test reviews for the purpose of our systematic review on prognostic test accuracy. The certainty in the evidence will be assessed for true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN), as suggested by GRADE.12 In brief, the application of GRADE will be conducted as follows:

For each body of evidence on diagnostic studies, all studies start as ‘high’. ‘True positives’, ‘true negatives’, ‘false positives’ and ‘false negatives’ are defined as outcomes.

Risk of bias is assessed by the QUADAS-2 tool, and evidence quality can be downgraded, if necessary.

Thereafter, the other GRADE criteria for downgrading quality of evidence (inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias) are applied, according to the approach published by the GRADE working group.12

Risk factor approach: We will use the GRADE approach to risk factor/prognostic factor studies. The certainty in the evidence will be assessed for the outcome late-onset sepsis according to the GRADE methodology28 as follows:

For each body of evidence, certainty in the evidence is initially rated as ‘high’, irrespective of study design.

Risk of bias is assessed by the appropriate risk of bias tool, and evidence certainty can be downgraded, if necessary.

Thereafter, the other GRADE criteria for downgrading quality of evidence (inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias) are applied.

Upgrading of the quality of evidence is possible, according to the criteria introduced by GRADE.

Reporting of this review

The systematic review will be reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. The PRISMA checklist will be published with the report.

Dissemination of findings

The resulting systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal as an open access paper.

Acknowledgments

This systematic review will be performed as part of the piloting phase of the PRECEPT project. PRECEPT is funded by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC; tenders no. 2012/040; 2014/008).

Footnotes

Contributors: TH, JS and SH developed the concept of this protocol. TH wrote the first draft. JS, BW, TE and SH provided important intellectual input to revise the draft protocol. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted. TH is the guarantor of this protocol.

Funding: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; grant number (2012/040; 2014/008).

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the development and writing of this protocol.

Ethics approval: This study will not require ethical approval since it is not carried out in humans.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Smith A, Saiman L, Zhou J et al. Concordance of gastrointestinal tract colonization and subsequent bloodstream infections with gram-negative Bacilli in very low birth weight infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010;29:831–5. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e7884f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vergnano S, Menson E, Kennea N et al. Neonatal infections in England: the NeonIN surveillance network. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F9–F14. 10.1136/adc.2009.178798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alshaikh B, Yusuf K, Sauve R. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants with neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol 2013;33:558–64. 10.1038/jp.2012.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordero L, Rau R, Taylor D et al. Enteric gram-negative bacilli bloodstream infections: 17 years’ experience in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:189–95. 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2002;110:285–91. 10.1542/peds.110.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprunt K, Leidy G, Redman W. Abnormal colonization of neonates in an intensive care unit: means of identifying neonates at risk of infection. Pediatr Res 1978;12:998–1002. 10.1203/00006450-197810000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobson SR, Isaacs D, Wilkinson AR et al. Reduced use of surface cultures for suspected neonatal sepsis and surveillance. Arch Dis Child 1992;67:44–7. 10.1136/adc.67.1_Spec_No.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox GP, Clarke TA, Matthews TG. Are routine superficial cultures worth while in neonatal practice? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:1443 10.1136/bmj.296.6634.1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau YL, Hey E. Sensitivity and specificity of daily tracheal aspirate cultures in predicting organisms causing bacteremia in ventilated neonates. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991;10:290–4. 10.1097/00006454-199104000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slagle TA, Bifano EM, Wolf JW et al. Routine endotracheal cultures for the prediction of sepsis in ventilated babies. Arch Dis Child 1989;64:34–8. 10.1136/adc.64.1_Spec_No.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harder T, Abu Sin M, Bosch-Capblanch X et al. Towards a framework for evaluating and grading evidence in public health. Health Policy 2015;119:732–6. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008;336:1106–10. 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wald NJ, Hackshaw AK, Frost CD. When can a risk factor be used as a worthwhile screening test?. BMJ 1999;319:1562–5. 10.1136/bmj.319.7224.1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G et al. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:882–90. 10.1093/aje/kwh101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JH. The limitations of risk factors as prognostic tools. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2615–17. 10.1056/NEJMp068249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dretzke J, Ensor J, Bayliss S et al. Methodological issues and recommendations for systematic reviews of prognostic studies: an example from cardiovascular disease. Syst Rev 2014;3:140 10.1186/2046-4053-3-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young YR, Sheu BF, Li WC et al. Predictive value of plasma brain natriuretic peptide for postoperative cardiac complications--a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2014;29:696 e1–10. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z, Yao Z, Li C et al. A step-by-step guide to the systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic and prognostic test accuracy evaluations. Br J Cancer 2013;108:2299–303. 10.1038/bjc.2013.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rector TS, Taylor BC, Wilt TJ. Chapter 12: systematic review of prognostic tests. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(Suppl 1):S94–101. 10.1007/s11606-011-1899-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lurati Buse GA, Koller MT, Burkhart C et al. The predictive value of preoperative natriuretic peptide concentrations in adults undergoing surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2011;112:1019–33. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820f286f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van't Hooft J, van der Lee JH, Opmeer BC et al. Predicting developmental outcomes in premature infants by term equivalent MRI: systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2015;4:71 10.1186/s13643-015-0058-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL et al. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:280–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harder T, Takla A, Rehfuess E et al. Evidence-based decision-making in infectious diseases epidemiology, prevention and control: matching research questions to study designs and quality appraisal tools. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:69 10.1186/1471-2288-14-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med 2001;20:2865–84. 10.1002/sim.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW et al. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:982–90. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ 2015;350:h870 10.1136/bmj.h870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014986supp_appendix.pdf (234.7KB, pdf)