Abstract

Background

The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) during pregnancy is poorly understood in Egypt—a country with a high birth rate.

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of ASB among pregnant women booking at El Hussein and Sayed Galal Hospitals in Al-Azhar University in Egypt; and to observe the relationship between ASB prevalence and risk factors such as socioeconomic level and personal hygiene.

Setting

Obstetrics and gynaecology clinics of 2 university hospitals in the capital of Egypt. Both hospitals are teaching and referral hospitals receiving referrals from across over the country. They operate specialist antenatal clinics 6 days per week.

Participants

A cross-sectional study combining the use of questionnaires and laboratory analysis was conducted in 171 pregnant women with no signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection (1 case was excluded). Samples of clean catch midstream urine were collected and cultured using quantitative urine culture and antibiotic sensitivity tests were performed.

Results

Of 171 pregnant women, 1 case was excluded; 17 cases (10%, 95% CI 5.93% to 15.53%) were positive for ASB. There was a statistically significant relation between the direction of washing genitals and sexual activity per week—and ASB. Escherichia coli was the most commonly isolated bacteria followed by Klebsiella. Nitrofurantoin showed 100% sensitivity, while 88% of the isolates were resistant to cephalexin.

Conclusions

The prevalence of ASB seen in pregnant women in 2 tertiary hospitals in Egypt was 10%. E. coli and Klebsiella are the common organisms isolated. The direction of washing genitals and sexual activity significantly influences the risk of ASB. Pregnant women should be screened early for ASB during pregnancy; appropriate treatment should be given for positive cases according to antibiotic sensitivity screening. Cephalexin is likely to be of limited use in this management.

Keywords: Asymptomatic Bacteriuria, Urinary Tract Infection, Urine Culture, Egypt

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study holds implications for clinical providers and policymakers in Egypt regarding screening and prevention of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB).

This study provides the first insights into the prevalence of ASB among pregnant women in Egypt; and outlines causative organisms, risk factors and appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Negatives of this study include:

- Positive cases with ASB were not followed-up to determine their adverse outcomes.

- We were unable to track patients through follow-up urine specimen testing to determine efficacy of antimicrobial treatment.

- With greater study duration, more patients would be enrolled strengthening the power of the study.

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common infections during pregnancy, affecting up to 20% of expectant mothers.1 2 It is defined as microbial contamination of the urine as well as tissue invasion of any part of the urinary tract.3 UTI does not always cause signs and symptoms; if asymptomatic but the urine still contains a significant number of ≥105 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL of bacteria, this condition is termed asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB).4 ASB during pregnancy is influenced by a range of physiological and anatomical factors, including mechanical compression and changes in the immune and renal systems.5 In addition, there are a range of risk factors that predispose expectant mothers to developing ASB including age, gestational stage, parity, sexual activities and other factors as summarised in the online supplementary appendix table S1.6–8

bmjopen-2016-013198supp_appendix.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

The prevalence of ASB ranges from 2% to 11% during pregnancy;5 9–11 Escherichia coli is found in 70–90% of isolates that cause ASB.12 13 Other bacteria involved include Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus Saprophyticus.13 14 Most of these pathogens exist naturally in the periurethral area and in the perianal area—and their ascension through the urethral orifice can lead to UTI.12 15 Quantitative urine culture is the gold standard for diagnosis of ASB—the optimal time for screening is the 16th gestational week.16 If ASB is left undiagnosed, there is a risk of developing acute pyelonephritis, seen in up to 40% of pregnant women.6 13 17 Pyelonephritis is associated with preterm labour,12 which is one of the main contributors to neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide.

Early diagnosis and treatment of ASB can drastically reduce the incidence of pyelonephritis,18 and prevent preterm labour by up to 20%.4 However, in developing countries, including Egypt, screening for ASB in pregnancy is not viewed as an essential component of antenatal care; and as a result, there is little understanding of the prevalence of ASB. This is particularly important given Egypt's high birth rate of 23.35 births/1000 population—nearly double that seen in Western Europe or the USA.19 Accordingly, this study—conducted in two teaching and referral hospitals in Egypt—sought to determine the prevalence of ASB during pregnancy, identify the causative organisms and antibiotic sensitivity, and establish the relationship between ASB and common risk factors; with the aim of making recommendations to improve obstetric practice in Egypt and other middle-income countries.

Methodology

Study design

The study was a cross-sectional study combining the use of questionnaires and laboratory analysis of samples obtained from participants (questionnaire survey used is included in the online supplementary appendix figure S1) between January and February 2016 at the obstetrics and gynaecology clinics of El Hussein and Sayed Galal Hospitals of Al-Azhar University in Cairo Governorate which is the capital of Egypt. Both hospitals are teaching and referral hospitals receiving patients from across the country.

Study procedures

Pregnant females were interviewed using precoded, pretested, interviewer-administered questionnaires to collect and record maternal social demographic characteristics. Laboratory forms were used to record data and results after sample analysis.

Selection criteria

The full study inclusion criteria are included in the online supplementary appendix figure S2. Briefly, pregnant women aged 18–41 years attending the antenatal clinic sites of this study were invited to enrol. Exclusion criteria included a history of UTI or recent use of antibiotics. Participants were asked to provide blood and urine sample for further testing as described below. We had excess of 10% participant recruitment to meet the expected non-response or loss of questionnaires, giving a minimum sample size of 121 cases. The sample size was increased to 171 cases to maximise the validity of the study and improve the data quality measures.20 Further details are included in the online supplementary appendix figure S3.

Data management/analysis

Data were entered into a secured personal computer using Microsoft Excel software and analysed using Epi Info V.7.2 computer software. Frequency distribution of selected variables was performed first. Means were compared using the t-test and χ2 test was used to assess the difference between proportions. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

Agreement for this study was obtained from the hospital's ethical committee, and informed consent was obtained from pregnant women after adequate provision of information regarding the study requirements, purpose and risks. Further details are included in the online supplementary appendix figure S4.

Laboratory investigations

Blood samples

From each participant, 5 mL of blood sample was collected; 2 mL in EDTA-containing tube and tested for complete blood count (CBC) using an automated CBC analyser (Sysmex KX-21N) and the remaining 3 mL of blood was collected in a plain tube, left to coagulate and then centrifuged. The serum was kept in an Eppendorf tube at 0°C for further tests; blood glucose levels were measured using a Hitachi modular analyser (Roche cobas 8000) and rapid HIV test was performed using ELISA (IMMULITE 2000).

Urine samples

Urine collection and macroscopy

Participants were taught how to collect midstream urine in a sterile universal bottle. The sample processing was carried out within 4 hours of specimen collection. Urine samples were examined macroscopically by observing the colour, aspect, deposit and blood clots or debris. Each sample was divided into three portions: microscopic analysis, culture and chemical analysis to avoid contamination of the samples.

About 5 mL of each well-mixed urine sample was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. A drop of properly mixed sediment was placed on a glass slide and examined under light microscope to detect pus cells (indicating ingested bacteria), Trichomonas vaginalis, Schistosoma ova, white cell count, red blood cells, casts, crystals and yeast-like cells. The presence of 10 pus cells/mm3 or more was regarded as pyuria.21 Drops of the urine were applied to microscope slides, allowed to air dry, stained with Gram stain, and examined microscopically (primary Gram staining). Quality control was performed.22 The supernatant of the centrifuged urine was tested using Combi screen 10 urinalysis strips, with the existence of nitrite and leucocyte esterase in the urine being suggestive of infection.23 24

Culturing of bacteria from urine samples

A sterile disposable calibrated loop delivering 0.01 mL of urine was used for streaking cystine lactose electrolyte deficient (CLED) agar plates following standard procedure.25 Specimens were also streaked on the blood agar plate and MacConkey agar plate and then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, the CLED agar plates were observed for confluent growth, which shows significant bacteriuria, and if not confluent, the colonies were counted then multiplied by the size of the inoculums of the calibrated loop, which is 1/100. Significant ASB was considered when the bacterial value was ≥105. For cultures with no or insignificant bacterial growths, incubation was continued for a further 24 hours. After a description of colonies, Gram staining was performed from pure colonies. Biochemical tests were performed from the pure colonies for identification. The antibiogram determination was performed using pure colonies from the CLED agar plates.

Sensitivity tests

Organisms showing significant bacteriuria were inoculated into peptone water before plating on Mueller-Hinton agar. Commercially organised antimicrobial discs of known minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were placed over the surface of the sensitivity agar and pressed down with sterile forceps to make enough contact with the agar. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and the zones of growth inhibition were estimated.26 The antimicrobial sensitivity discs used were: amoxycillin-clavulanate, imipenem, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefuroxime, cefaclor, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, amikacin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Results

A total of 171 pregnant women were examined for ASB; 1 case was excluded (microscopic urine analysis reported pus cells more than 10 cells/high-power field (HPF)). Hence, 170 pregnant women were included in this study. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the participants and their ASB results. The mean age of patients was 28.52±5.36 years ranging from 18 to 41 years. Among the participants, 75% were in their third trimester, 70% were multiparous; regarding their educational status—47% had completed high school; 61% were in a ‘low’ socioeconomic level based on (Kuppuswamy's Socio-economic Status (SES) Scale for 2016) online tool.27

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of pregnant women included in this study

| Characteristics | Frequency | Positive culture (N) | Percentage | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| <20 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 20–30 | 114 | 12 | 11 | 0.29 |

| >30 | 54 | 5 | 9 | |

| Gestational age | ||||

| First trimester | 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| Second trimester | 27 | 5 | 19 | 0.86 |

| Third trimester | 129 | 12 | 9 | |

| Parity | ||||

| Grand multipara | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiparous | 119 | 13 | 11 | |

| Primigravida | 39 | 4 | 10 | 0.11 |

| Educational level | ||||

| College | 19 | 1 | 6 | |

| Elementary | 15 | 1 | 7 | |

| Graduate | 32 | 3 | 9 | 0.69 |

| High school | 80 | 10 | 13 | |

| Junior school | 24 | 2 | 8 | |

| Socioeconomic level | ||||

| High | 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intermediate | 52 | 3 | 6 | 0.08 |

| Low | 104 | 14 | 13 | |

| Direction of wash genitals | ||||

| Back to front | 102 | 15 | 15 | |

| Front to back | 68 | 2 | 3 | 0.03 |

| Number of bathing and changing underwear (week) | ||||

| 1–3 times | 119 | 12 | 10 | |

| >3 times | 51 | 5 | 10 | 0.69 |

| Number of sexual intercourse (week) | ||||

| 1–2 times | 92 | 6 | 7 | |

| >2 times | 78 | 11 | 14 | 0.01 |

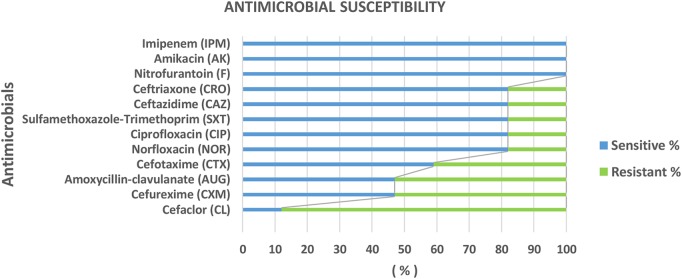

Of the 170 pregnant women tested, 17 cases were positive for significant bacteriuria (CFU≥105/mL), giving an overall prevalence of 10% (95% CI 5.93% to 15.53%; figure 1A). E. coli was the most predominant organism followed by Klebsiella; no other isolated organisms showed significant growth (figure 1B). On microscopic examination of positive cases, 10 (59%) had pus cells (<10)/HPF, 5 cases (29%) had red blood cells, 1 case (6%) had epithelial cells and 1 case (6%) had crystals (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Urine culture and microscopic urinalysis. Proportion (%) of pregnant women with ASB in the study (A); proportions of causative uropathogens isolated from positive cases (B); microscopic analysis of bacterially positive urine cases (C). ASB, asymptomatic bacteriuria; E. coli, Escherichia coli; RBC, red blood cell.

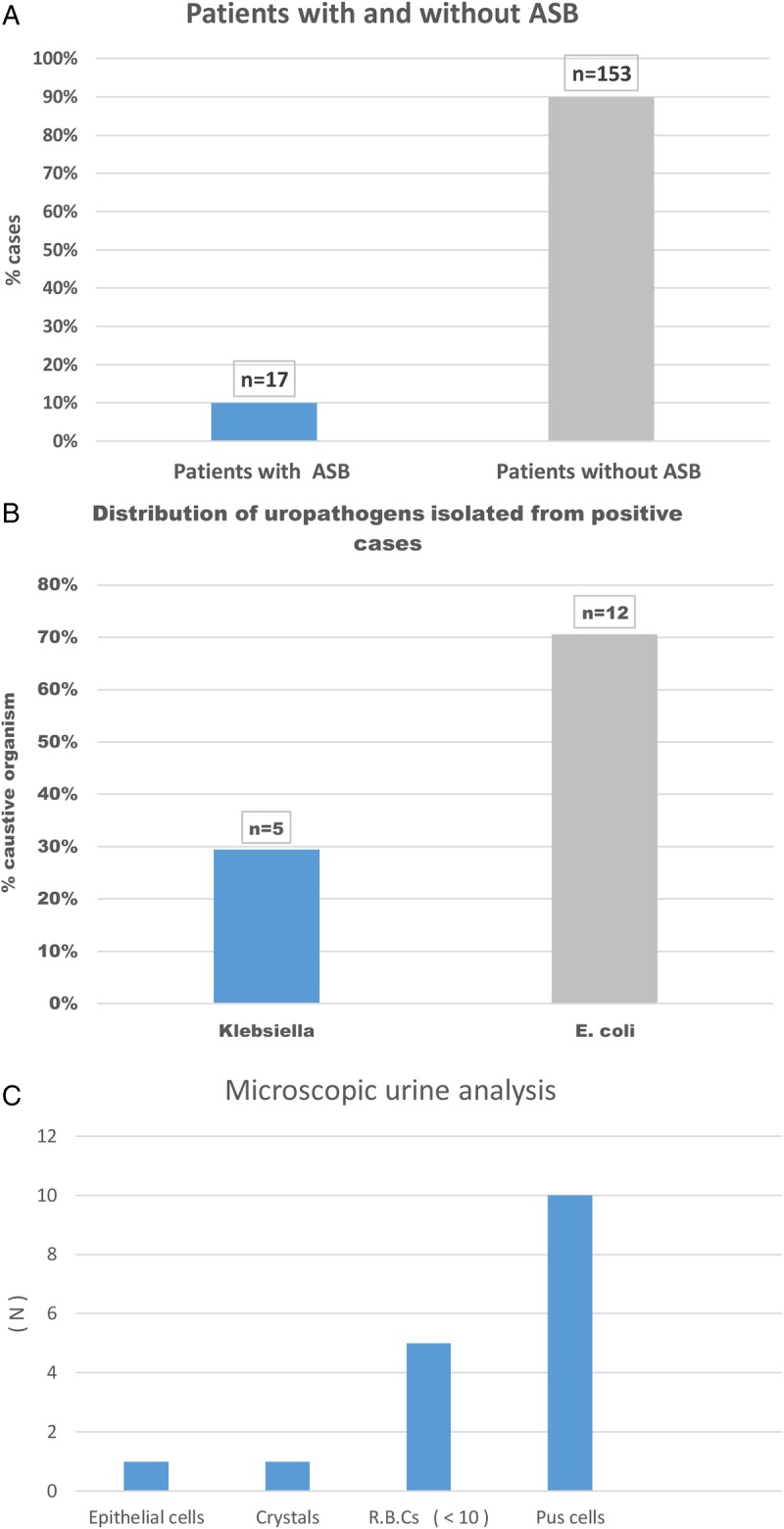

We then examined the sensitivity of these to antibiotics. Overall, nitrofurantoin, imipenem and amikacin demonstrated 100% sensitivity (figure 2). A range of other antibiotics showed good sensitivity including norfloxacin and ceftazidime; however, 88% of the urinary isolates were resistant to cephalexin (figure 2). Investigating whether there were isolate-specific differences in antimicrobial susceptibility, we found that only E. coli demonstrated resistance across the range of antibiotics tested (table 2). However, of note, cephalexin showed poor efficacy across both bacteria.

Figure 2.

The proportion (%) of sensitivity/resistance susceptibility of isolated bacteria to different antibiotics using discs' diffusion method; commercially purchased antimicrobial discs of known MICs were placed aseptically over the surface of the sensitivity agar. The plates were incubated for 24 hours, and the zones of growth inhibition were estimated. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Table 2.

Susceptibility of isolated uropathogens to different antibiotics using discs' diffusion method

| Organism sensitivity N (%) Antibiotic |

E. coli sensitive N (%) | Klebsiella sensitive N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| AUG | 3 (25%) | 5 (100%) |

| CAZ | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%) |

| CRO | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%) |

| CTX | 5 (41.7%) | 5 (100%) |

| CXM | 5 (41.7%) | 3 (60%) |

| F | 12 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| NOR | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%) |

| CIP | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%) |

| AK | 12 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| SXT | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%) |

| IPM | 12 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| CL | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) |

Positive cases=17; E. coli=12 cases; Klebsiella=5 cases.

AUG, amoxycillin-clavulanate; AK, amikacin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CL, cefaclor; CRO, ceftriaxone; CTX, cefotaxime; CXM, cefuroxime; E. coli, Escherichia coli; F, nitrofurantoin; IPM, imipenem; NOR, norfloxacin; SXT, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Regarding the relationship between ASB and the range of demographic and personal hygiene risk factors examined in this study, ASB was predominant in participants with higher sexual activity: 78 (65%) participants reported their sexual activity as greater than twice per week, and 11 of the 17 ASB cases were seen in this cohort (p=0.01). ASB was also significantly higher among participants who reported washing their genitals from back to front after defaecation (88%, p=0.03; table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between ASB and age, gestational age, parity, educational level, socioeconomic level or haemoglobin concentration (table 1). No HIV+ cases were identified in this study.

Discussion

In the present study, the prevalence of ASB during pregnancy was found to be 10% (95% CI 5.93% to 15.53%). The prevalence in this study is comparable to that reported in Nigeria,14 but lower than studies from Ethiopia.28–31 These discrepancies between and within countries may be due to differences in the study participants' socioeconomic levels, and cultural7 and religious behaviours related to personal hygiene and sexual contact.

ASB had a significant relationship with sexual activity as seen in other studies.32 33 Sexual intercourse may increase the probability of transfer of uropathogens into the urethra; and as reported elsewhere, ASB had a significant relationship with the direction of washing genitals after urination or defaecation.34 Washing of genitals from back to front is more likely to lead to the spread of anal or vaginal flora into the urethra. Education on the direction of washing and advice to micturate shortly after sexual activity can reduce the prevalence of UTI.35

However, there was no statistically significant association between parity, maternal age, socioeconomic class, educational level or gestational age and ASB (p>0.05). This is most probably because of the small sample size. Multiparous women had the highest frequency of ASB, similar to findings in another study.36 This is believed to be because high parity leads to the descent of pelvic organs, and a widening of the urethral orifice, which influences the ascent of microbes.37–39 ASB appears predominant in women aged between 20 and 30 years, which is similar to findings from other studies.40 41 The vulnerability of these age groups could be explained by early and intensive sexual intercourse which may cause minor urethral trauma and transfer bacteria from the perineum into the bladder.42

Accurate diagnosis of causative organisms is critical to the appropriate selection and completion of an antibiotic course. In this study, E. coli and Klebsiella were causative, with E. coli dominant in most cases, as reported previously.40 41 43 Choice of antibiotics must also consider potential side effects; while all isolates were sensitive to nitrofurantoin, there have been concerns over its potential impacts on the fetus.12 Of concern for clinicians, 88% of E. coli and Klebsiella isolates in this study were resistant to cephalexin. The antimicrobial sensitivity and resistance patterns vary between communities and hospitals. This is likely because of the emergence of resistant strains, caused in part by inappropriate antibiotic prescription. Today, antimicrobial resistance is recognised as a looming international health crisis;44 and as such is now a global health priority. Certain regions are already experiencing high levels of bacterial resistance rates to common frontline antibiotics such as amoxicillin or ampicillin.13 Accordingly, a range of guidelines has been established for the screening and diagnosis of ASB, including from the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA.45 46

Early and regular check-ups by medical providers are vital in assessing the physical status and early recognition of complications during pregnancy. Yet, the provision of regular antenatal care is still low in Egypt, especially in rural areas. Antenatal care coverage for at least one visit is 74% and antenatal care coverage for at least four visits is 66%; 69% of pregnant women are examined by routine urine analysis only.47 48 These findings, combined with the prevalence of ASB found in this study betray an antenatal care system in need of improvement. This is all the more urgent given the high fertility rate in Egypt, on average 3.5 children per woman compared with 1.83 in the UK.49

The implications of this study for clinical providers and policymakers in Egypt are threefold. First, physicians must be educated on the importance of screening and prevention of ASB, and informed of the latest antimicrobial resistance data in their country or region. Second, pregnant women must be educated on personal hygiene and ASB to ensure they recognise the implications for their health and their children; and third, policymakers must recognise the cost-benefits of diagnosis of ASB early before it progresses to other more serious diseases such as pyelonephritis and preterm labour.

Recommendations

Screening for ASB must become an essential part of antenatal care. We recommend periodic screening at each trimester especially at 9–17 gestational weeks by quantitative urine culture.

Selection of the appropriate antibiotic based on antibiotic sensitivity testing of uropathogens (control resistant strains in the future). It is important to remember that therapy must be safe for mother and fetus; the practice should be guided by bacterial sensitivity/resistance profiles.

Nitrofurantoin is recommended to be used for patients in the first and second trimesters, as it is cheap, showed 100% sensitivity and is reported safe and efficacious in the treatment of ASB during pregnancy; however, concerns exist for its use in the third trimester. This antibiotic could replace cephalosporins (if isolates show sensitivity to it).50–52

Conclusion

The prevalence of ASB seen in pregnant women in two tertiary hospitals in Egypt was 10%. E. coli was the dominant organism isolated. The direction of washing genitals and sexual activity significantly influences the risk of ASB. Quantitative urine culture is the ideal test for detection of ASB. Nitrofurantoin is the most efficient antimicrobial for the treatment of ASB. Early detection and treatment are essential to safeguard the health of mother and fetus. Further larger studies could provide cost-benefit data9 53 54 necessary to inform a national screening programme.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have participated fully in the conception, writing and critical review of this manuscript. All have seen and agreed to the submission of the final manuscript. MA-AE is the first author, principle investigator, and was involved in design of the work, data collection, sample collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing and drafting the article. AB-V was involved in writing and critical review. MFED is the laboratory physician, and was involved in sample collection and processing, writing, and critical review. FC is the corresponding author, and was involved in writing and critical review.

Funding: The project was financed by Chinese Government Scholarship ‘Youth of Excellence Scheme Of China (Yes China)’.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: El Hussein and Sayed Galal Hospital's Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendices of survey questions and additional data are included in the online supplementary material.

References

- 1.Parveen K, Momen A, Begum AA et al. . Prevalence of urinary tract infection during pregnancy. J Dhaka Natl Med Coll Hosp 2012;17:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebidor UL, Tolulope A, Deborah O. Urinary tract infection amongst pregnant women in Amassoma, Southern Nigeria. Afr J Microbiol Res 2015;9:355–9. 10.5897/AJMR2014.7323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Najar MS, Saldanha CL, Banday KA. Approach to urinary tract infections. Indian J Nephrol 2009;19:129–39. 10.4103/0971-4065.59333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazemier BM, Schneeberger C, De Miranda E et al. . Costs and effects of screening and treating low risk women with a singleton pregnancy for asymptomatic bacteriuria, the ASB study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:52 10.1186/1471-2393-12-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghafari M, Baigi V, Cheraghi Z et al. . The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in Iranian pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0158031 10.1371/journal.pone.0158031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain V, Das V, Agarwal A et al. . Asymptomatic bacteriuria & obstetric outcome following treatment in early versus late pregnancy in north Indian women. Indian J Med Res 2013;137:753–8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3724257&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract (accessed 25 Nov 2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muharram SH, Ghazali SNB, Yaakub HR et al. . A preliminary assessment of asymptomatic bacteriuria of pregnancy in Brunei Darussalam. Malaysian J Med Sci 2014;21:34–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smaill F, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD000490 10.1002/14651858.CD000490.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazhir S. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women. Urol J 2007;4:24–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jassim ZM. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and pyuria in pregnant women in Hilla city: causative agents and antibiotic sensitivity. J Babylon Univ 2013;21:2755. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sau-yee F, Ny F, Hy H. The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant Hong Kong women. Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obs Midwifery 2012;16:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnarr J, Smaill F. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and symptomatic urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Eur J Clin Invest 2008;38(Suppl 2): 50–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le J, Briggs GG, McKeown A et al. . Urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Urin Tract Infect J 2004;3:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aminu KY, Aliyu UU. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women in the antenatal booking clinic at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, Nigeria. Open J Obstet Gynecol 2015;5:286–97. 10.4236/ojog.2015.55042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khazal N, Hindi K, Hasson SO et al. . Bacteriological study of urinary tract infections with antibiotics susceptibility to bacterial isolates among honeymoon women in Al Qassim Hospital, Babylon Province, Iraq. Br Biotechnol J 2013;3:332–40. 10.9734/BBJ/2013/3573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenqvist K, Dahlén-Nilsson I, Lidin-Janson G et al. . Bacteriuria in pregnancy. Frequency and risk of acquisition. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:372–9. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung KL, Lafayette RA. Renal physiology of pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2013;20:209–14. 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matuszkiewicz-rowińska J, Małyszko J, Wieliczko M. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy: old and new unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic problems. Arch Med Sci 2015;11:67–77. 10.5114/aoms.2013.39202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breu F, Guggenbichler S, Wollmann J. World Health Statistics. 2013. Geneva: WHO Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Requirements SS, Difference M. 19: Sample size, precision, and power sample size requirements for estimating a mean or mean difference sample size requirements for testing a mean or mean difference. Power 2000;1:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alnaaimi AS, Sabri M. Validity of pyuria and bacteriuria (detected by Gram-stain) in predicting positive urine culture in asymptomatic female children Rajah JT Al-Ma'amoory*. 2007;20:349–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ismail M, Assurance Q. Quality assurance in. Indian J Med Microbiol 2011;22:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simerville JA, Maxted WC, Pahira JJ. Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:1153–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmiemann G, Kniehl E, Gebhardt K et al. . The diagnosis of urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Dtsch Ärzteblatt Int 2010;107:361–7. 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Services M. UK standards for microbiology investigations. Bacteriol Health Engl 2015;B 55:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaifali I, Gupta U, Mahmood SE et al. . Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of urinary pathogens in female outpatients. N Am J Med Sci 2012;4:163–9. 10.4103/1947-2714.94940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma R. Online interactive calculator for real-time update of the Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale. http://www.scaleupdate.weebly.com (accessed 5 Mar 2016).

- 28.Tadesse E, Teshome M, Merid Y et al. . Asymptomatic urinary tract infection among pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic of Hawassa Referral Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:155 10.1186/1756-0500-7-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oli AN, Okafor CI, Ibezim EC et al. . The prevalence and bacteriology of asymptomatic bacteriuria among antenatal patients in Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Nnewi; South Eastern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2010;13:409–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajaratnam A, Baby NM, Kuruvilla TS et al. . Diagnosis of asymptomatic bacteriuria and associated risk factors among pregnant women in Mangalore, Karnataka state. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:OC23–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kehinde AO, Adedapo KS, Aimaikhu CO et al. . Significant bacteriuria among asymptomatic antenatal clinic attendees in Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop Med Health 2011;39:73–6. 10.2149/tmh.2011-02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amala SE, Nwokah EG. Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant women attending antenatal in Port Harcourt Township, Nigeria and antibiogram of isolated bacteria. Am J Biomed Sci 2015;7:125–33. 10.5099/aj150200125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labi A-K, Yawson AE, Ganyaglo GY et al. . Prevalence and associated risk factors of asymptomatic bacteriuria in ante-natal clients in a large teaching hospital in Ghana. Ghana Med J 2015;49:154–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obiora CC, Dim CC, Ezegwui HU et al. . Asymptomatic bacteriuria among pregnant women with sickle cell trait in Enugu, South Eastern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2014;17:95–9. 10.4103/1119-3077.122856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moustafa MF, Makhlouf EM. Association between the hygiene practices for genital organs and sexual activity on urinary tract infection in pregnant women at women's Health Center, at Assiut University Hospital. J Am Sci 2012;8:515–22. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nisha AK, Etana AE, Tesso H. Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy in Adama city, Ethiopia. Int J Microbiol Immunol Res 2015;3:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fong SY, Tung CW, Yu YNY et al. . The Prevalence of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Pregnant Hong Kong Women Hong Kong J Gynaecol Obstet Midwifery 2013;13:40–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shruthi A. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: bacteriological profile and antibiotic sensitivity pattern in a tertiary care hospital, Bengaluru. Int J Health Sci Res 2015;5:157–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ojide CK, Wagbatsoma VA, Kalu EI. Asymptomatic bacteriuria among antenatal care women in a tertiary hospital in Benin, Nigeria. Niger J Exp Clin Biosci 2014;2:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sujatha R, Nawani M. Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and its antibacterial susceptibility pattern among pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic at Kanpur, India. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:2–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan S, Singh P, Siddiqui Z et al. . Pregnancy-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria and drug resistance. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2015;10:340–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jalali M, Shamsi M, Roozbehani N et al. . Prevalence of urinary tract infection and some factors affected in pregnant women in Iran Karaj City 2013. Middle East J Sci Res 2014;20:781–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olamijulo JA, Adewale CO, Olaleye O. Asymptomatic bacteriuria among antenatal women in Lagos. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore) 2016;3615:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smaill F. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:439–50. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Catherine M. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. External review against programme appraisal criteria for the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC). UK Natl Screen Com 2011;2:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Zanaty F, Way A. Egypt Demographic and Health Survey—the DHS Program ICF International Rockville, Maryland, U.S.A. Minist Health Popul 2005;2:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Care P. Children in Egypt Chapter 2 Births and Perinatal Care. Published Online First: 2015. http://www.unicef.org/egypt/Children_in_Egypt-_data_digest_2014.pdf.

- 49.Office for National Statistics. Statistical Bulletin Births in England and Wales, 2013 2014;2012:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Johansen TEB, et al. Guidelines urological Infections. Published Online First: 2015. http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

- 51.Mittal P, Wing DA. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Clin Perinatol 2005;32:749–64. 10.1016/j.clp.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simoes JA, Aroutcheva AA, Heimler I et al. . Antibiotic resistance patterns of group B streptococcal clinical isolates. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2004;12:1–8. 10.1080/10647440410001722269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans DB, Edejer TT, Adam T et al. . Methods to assess the costs and health effects of interventions for improving health in developing countries. BMJ 2005;331:1137–40. 10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Selimuzzaman A, Ullah M, Haque M. Asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy: causative agents and their sensitivity in Rajshahi City. J Teach Assoc RMC 2006;19:66–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013198supp_appendix.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)