Abstract

Host genetic factors, such as histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs), are associated with susceptibility to norovirus (NoV) and rotavirus (RV) infections. Recent advances point to the gut microbiome as a key player necessary for a viral pathogen to cause infection. In vitro NoV attachment to host cells and resulting infections have been linked to interactions with certain bacterial types in the gut microbiota. We investigated the relationship between host genotype, gut microbiota, and viral infections. Saliva and fecal samples from 35 adult volunteers were analysed for secretor status genotype, the gut microbiota composition by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and salivary IgA titers to NoV and RV. Higher levels of IgA against NoV and RV were related to secretor-positive status. No significant differences were found between the FUT2 genotype groups, although the multivariate analysis showed a significant impact of host genotype on specific viral susceptibilities in the microbiome composition. A specific link was found between the abundance of certain bacterial groups, such as Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcus spp., and lower IgA titers against NoV and RV. As a conclusion, we can state that there is a link between host genetics, gut microbiota, and susceptibility to viral infections in humans.

Acute gastroenteritis (AGE) is a major worldwide health issue, associated with a high economic burden in developed countries and high annual mortality, particularly affecting children, in developing countries1. The major etiological agents of viral AGE in children are rotaviruses (RVs) (90% represented by RV group A [RVA])2 and noroviruses (NoVs)1.

It was previously shown that susceptibility to NoV infections differed between individuals3 and was associated with histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs)4. It has been suggested that HBGAs expressed on epithelial surfaces function as receptors for NoV, with different NoV strains showing different properties with regard to the ability to bind to different HBGAs5. Non-secretor individuals (lacking both functional FUT2 alleles) do not express H-antigen structures (Fucα1,2-Galβ1,3-GlcNAcβ1,3-Gal) on their mucosa and are less susceptible to NoV3. Based on the findings of recent publications6,7, the determination of susceptibility to RV infections should also consider HBGA phenotypes. Several studies have suggested that the non-secretor phenotype was restrictive to P[8] and P[4] RV genotype infections, as revealed in analyses of symptomatic infections6,8,9,10,11 or specific seral IgG levels12.

The gastrointestinal environment is a very complex ecosystem that contains a vast bacterial population in terms of numbers and diversity13. This population varies between individuals and is subject to changes depending on diverse factors, such as genetics, diet, and health status. Intestinal bacteria have a vast enzymatic potential for scavenging diet and host glycans (e.g., carbohydrate structures from O-glycosylated mucins and other HBGA structures on mucosal surfaces)14. Furthermore, the high L-fucose concentration in the gastrointestinal tract plays an important role in the ecology of this niche, assisting in commensal colonization15,16. Intestinal microbiome analyses have also revealed differences in the microbiota structure based on FUT2 status, with non-secretors showing reduced microbial richness compared to secretors17,18.

Some intestinal viruses rely on the microbiota for infectivity. No cell-culture system had previously allowed the in vitro replication of human NoV until recent findings showed that the NoV GII.4 genotype can infect human lymphocytic B cell line if an accompanying intestinal microbiota is present19. Moreover, NoV replication has been recently achieved in human enteroids derived from stem cells20. There are also evidences for microbiota-dependent RV infections in a study in which the use of germ-free animals or antibiotic treatments resulted in a >40% reduction of viral infections in a mouse model21.

In the present study, we analysed the link between secretor status, the gut microbiota, and susceptibility to RV and NoV infections in healthy individuals, measured via salivary IgA titers to RV and NoV. The expected link between secretor status and susceptibility to RV and NoV was found, and multivariate analyses showed that secretor status, the microbiota, and viral susceptibility are interdependent for both RV and NoV. Finally, specific correlations were found between certain bacterial groups and the risk of RV and NoV infections.

Results

Secretor status correlated with salivary anti-NoV and anti-RV titers

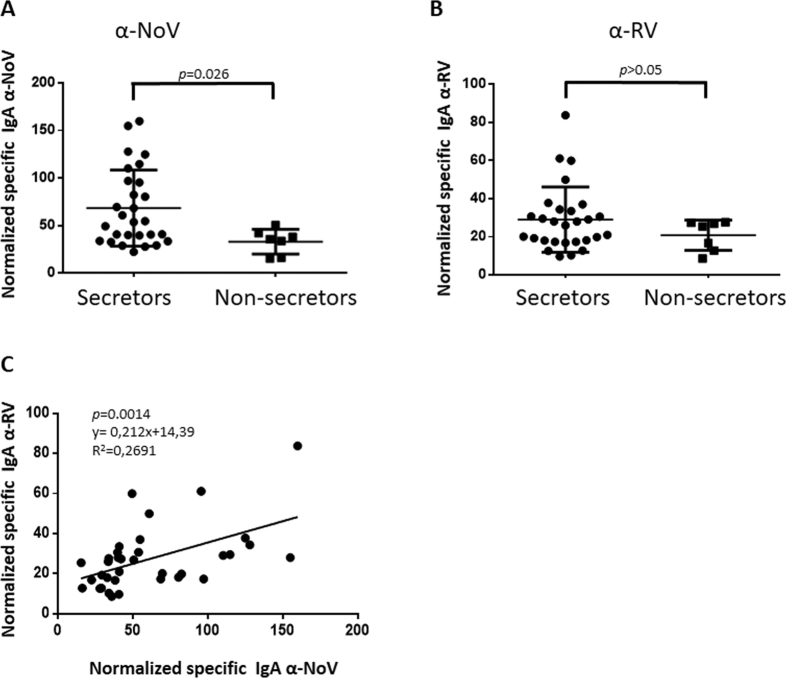

The aim of the present study was to identify relationships between viral susceptibility, host genetic factors, and the intestinal microbiota. To avoid invasive procedures, salivary IgA titers to NoV and RV were obtained. The proportion of non-secretor individuals in the studied population was 22.8%, which is in accordance with the prevalence of this phenotype in Caucasian populations (20%). The observed frequencies of the three genotypes (FUT2+/+(27.2%), FUT2+/− (50%) and FUT2−/− (22.8%) are in concordance with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p = 0.5974 for the deviation from the null hypothesis). The results confirmed that normalised salivary IgA titers against NoV are significantly higher (p < 0.05) in secretor-positive (FUT2+/+ or FUT2+/−) individuals than in non-secretor individuals (FUT2−/−) (Fig. 1A), as has been previously described based on analyses of serum IgG titers22. When normalised salivary anti-RV IgA titers were analysed, no significant differences were found between the groups, but the same tendency with regard to NoV was observed (Fig. 1B). The antibody titers against RV and NoV presented a positive correlation (p < 0.01) indicating that there is a relationship in the susceptibility to both viruses (Fig. 1C)

Figure 1.

Normalised specific salivary IgA against norovirus (NoV) (panel A) and against rotavirus (RV) (panel B) in a population of 28 secretor (9 FUT2+/+ and 19 FUT2+/−) and 7 non-secretor (FUT2−/−) individuals. The correlation between the IgA titers in both viruses is shown in panel C.

Microbiome composition

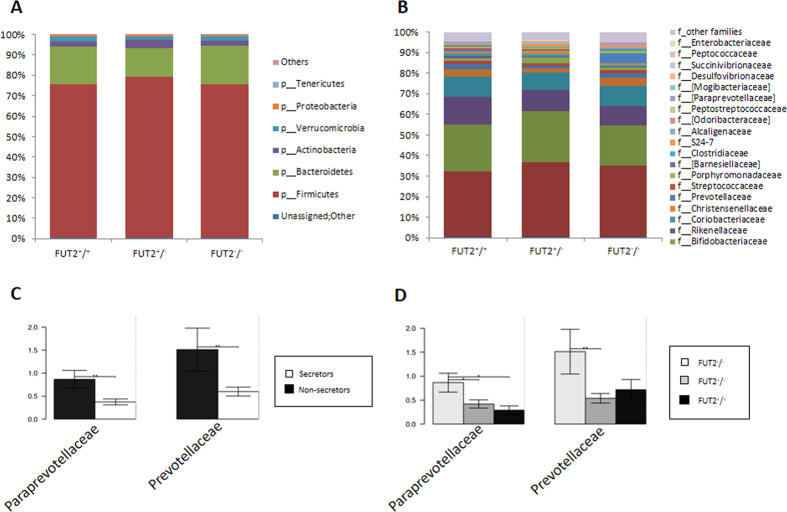

A total of 2,456,381 quality-filtered 16S rDNA sequences were obtained from the subjects’ feces, with an average of 70,182.3 ± 37,784.2 sequences per sample. These readings were clustered into 52,769 unique operational taxonomic units (OTUs), with an average of 1,500 OTUs per subject. The most abundant bacterial phyla were Firmicutes (76.01%), Bacteroidetes (17.27%), Actinobacteria (2.85%), and Verrucomicrobia (1.98%). Proteobacteria were present in less than 1%. At family level, the most predominant bacteria belonged to the Ruminococcaceae (35.58%), Lachnospiraceae (23.02%), Bacteroidaceae (11.36%), and other Clostridiales (9.66%), followed by Veillonellaceae (3.43%) and Verrucomicrobiaceae (2.00%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Relative abundance in % of the top phyla (Panel A) and families (Panel B) in the studied population including 7 non-secretor individuals (FUT2−/−), 9 homozygous secretor (FUT2+/+) and 19 heterozygous (FUT2+/−) individuals. Significantly different taxa at family level between secretor and non-secretors (Panel C) and FUT2 genotypes (Panel D) are shown as bar chart (p < 0.05, ANOVA). Standard error is depicted by error bars. Pair-wise comparisons are done by t-test and annotated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

No significant differences were found between the different FUT2 allele groups (FUT2+/+, FUT2+/− and FUT2−/−) at the phylum level (Fig. 2A). However, significantly higher levels were found in non-secretors (FUT2−/−) for the families Prevotellaceae and Paraprevotellaceae compared to secretors (FUT2+/+, FUT2+/−) (Fig. 2B,C and D). At the OTU level, we found significant differences in 16 OTUs, mostly belonging to the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla; these were predominantly more abundant in the non-secretors except for OTU Bacteroides_51792, which was more abundant in the secretors (Supplementary Figure S1). Six OTUs were different between the genotype groups (Supplementary Figure S2). UNIFRAC plots did not show different clusters between secretor and non-secretor (not shown). The Adonis analysis (permutational MANOVA [PERMANOVA]) showed no significant differences at the OTU level between the FUT2 groups (p = 0.179).

An alpha diversity analysis was performed on the samples after rarefaction to 12,100 sequences/sample (minimum sampling depth). Rarefaction curves generated for the Chao1 and Shannon indexes showed no differences between genotype groups (Supplementary Figure S3). Predictive functional profiling (PICRUSt) showed no significant differences between FUT2 groups and genotypes (not shown). The most predominant bacterial genes were related to metabolism, genetic information processing, and environmental information processing. We also performed LEfSe tests to detect KEGG pathways, with significantly different abundance levels in the samples, but we did not find significant differences between the secretor and non-secretor samples (LDA > 2, p > 0.05).

Intestinal microbiota correlates with susceptibility to RV and NoV

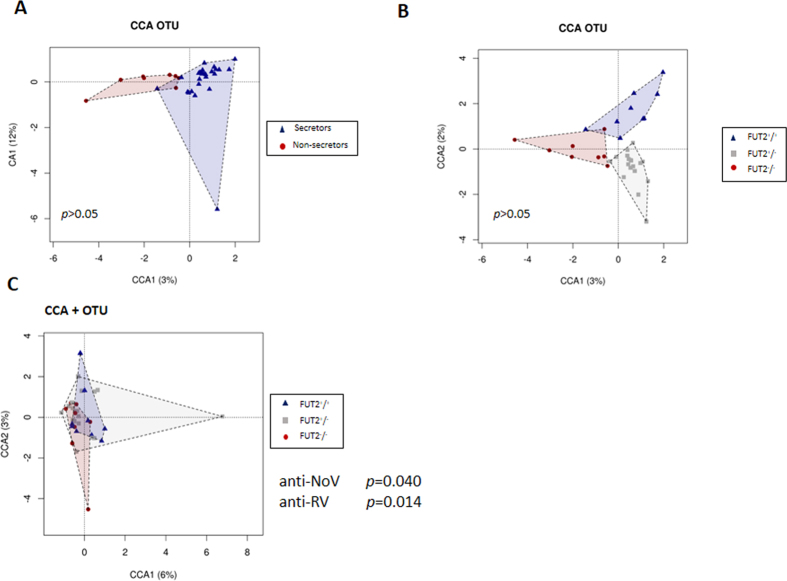

A multivariate canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) on the observed OTUs was performed. The plot showed clearly different groups in the microbial compositions between the non-secretors and the secretors at the phenotype and the genotype level although without significant differences (Fig. 3A and B, p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Multivariate analysis plots based microbiota composition at Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU) level between secretors (blue) and non-secretors (red) (Panel A) and also, between FUT2 genotypes (FUT2+/+ = blue, FUT2+/− = grey, FUT2−/− = red) (Panel B). Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA+) showing the relationship between gut microbiome composition of the FUT2 genotypes and both anti-virus IgA titers, anti-RV and anti-NoV respectively (Panel C). Anti-virus IgA titers significantly explain variations observed in the gut microbiota (p < 0.05).

We found that both, anti-NoV and anti-RV IgA levels, significantly explained the variations in the gut microbial composition associated to FUT2 secretor status (p = 0.040 and p = 0.014, respectively) on the CCA + analysis (Fig. 3C), confirming the hypothesis that all three factors (secretor status, microbiota, and susceptibility to RV and NoV) are interdependent.

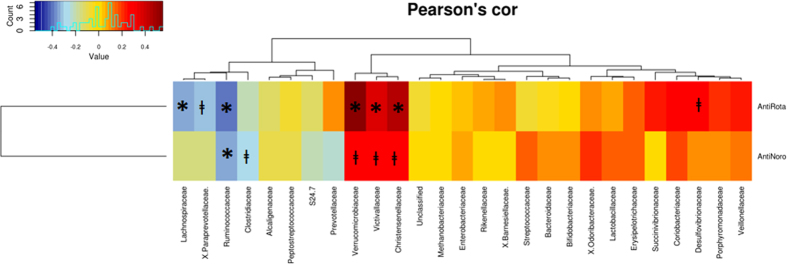

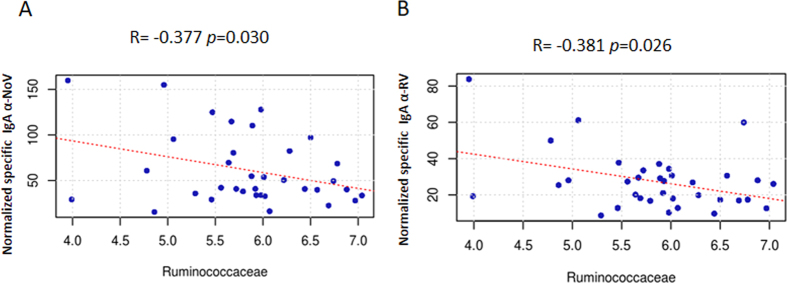

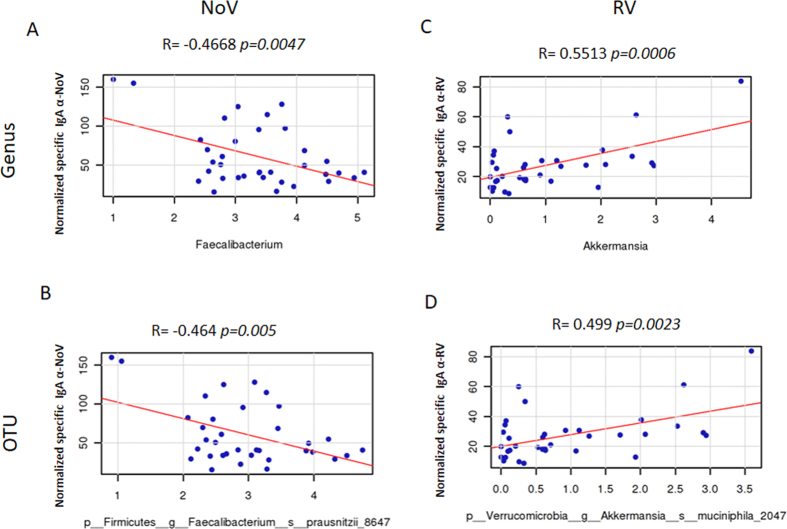

In order to seek out the relationships between specific bacterial groups and susceptibility to RV and NoV infections in humans, a Pearson correlation analysis was performed showing a potential link between gut microbiota composition and the susceptibility to RV and NoV infection (Fig. 4). The results showed a significant negative correlation between susceptibility to NoV (R = −0.377, p = 0.03) and RV infection (R = −0.381, p = 0.026) infection, with the number of bacteria from the Ruminococcaceae family (Fig. 5A and B, respectively) indicating that individuals with a greater abundance of Ruminococcaceae bacteria might have lower susceptibility to both types of viral infection. At genus level, a negative correlation between susceptibility to NoV and the abundance of Faecalibacterium (R = −0.4668, p = 0.0047) was observed (Fig. 6A). This correlation was confirmed at the OTU level, where a negative correlation (R = −0.464, p = 0.005) was found for NoV susceptibility and for the OTU F. prausnitzii_8647 (Fig. 6B). Another significant correlation was found between the OTU Ruminococcaceae_23936 (R = −0.3811, p = 0.024) and susceptibility to NoV. Different results were found among the different bacterial groups with regard to susceptibility to RV; a positive correlation was found at the genus level (R = 0.5513, p = 0.0006) between Akkermansia and susceptibility to RV (Fig. 6C). This correlation was confirmed at the OTU level, where a positive correlation was found between Akkermansia muciniphila_2047 and susceptibility to RV (R = 0.499, p = 0.0023) (Fig. 6D), indicating that the abundance of this bacterium correlates with increased susceptibility to RV infections. Other bacterial groups also correlated negatively with susceptibility to RV at the genus level, including Paraprevotella (R = −0.368, p = 0.03) and Faecalibacterium (R = −0.3319, p = 0.051). However, this last correlation did not reach significance. A similar level of significance was also seen at the OTU level, where F. prausnitzii_38832 showed a negative correlation with susceptibility to RV infection (R = −0.321, p = 0.06). A negative correlation was found between two different Ruminococcaceae OTUs, Ruminococcaceae_44932 (R = −0.3623, p = 0.032) and Ruminococcaceae_20617 (R = −0.357, p = 0.035), and susceptibility to RV infections.

Figure 4. Pearson correlations heatmap between the susceptibility to viral infection to rotavirus (RV) and norovirus (NoV) (measured as anti viral IgA titers) and the relative abundances of specific bacteria at family level.

R and p-values are indicated in the table. Sequences > 1% were included in the analysis. *p < 0.05 and ⱡp < 0.09.

Figure 5.

Pearson correlation plots at family level and the susceptibility to norovirus (NoV) (Panel A) and rotavirus (RV) (Panel B). The results show significantly associated correlation between the Ruminococcaceae family with Anti-IgA levels (p < 0.05). A scatter plot is shown plotting the abundance of the Ruminococcaceae family (x-axis) versus the anti-IgA titers (y-axis).

Figure 6.

Pearson correlation plots at genus and OTUS levels and the susceptibility to norovirus (NoV) (Panels A and B) and to rotavirus (RV) (Panels C and D). The p-values computed by correlation are reported indicating if the specific genus or OTU is significantly associated with Anti-IgA levels (p-values are indicated in each graphic).

Discussion

Recent research findings on the involvement of intestinal bacteria in NoV and RV infections have established that the microbiota plays a pivotal role in viral susceptibility19,21. Interestingly, this association exists even if these viruses replicate in the small intestine, whereas most of the intestinal bacteria are present in the colon. Susceptibility to NoV and RV infections has been related to HBGA types, but individual secretor status, linked to the FUT2 gene, is of special relevance. The presence of anti-RV and anti-NoV antibodies can be used as indicator of previous infections, constituting an indirect marker of virus susceptibility. We have seen that levels of specific secretory immunoglobulins (such as IgA) in the saliva relate to the secretor phenotype for NoV. This confirms the relevance of FUT2 in viral infectivity and indicates that, similar to humoral responses (serum IgG22), the secretory antibody response also serves as a marker for susceptibility. A trend-like correlation was only observed for RV, which may account for the higher variability of RV depending on secretor status, which is based on viral genotype, as has been described for P[8] and P[6] RV variants9.

NoV and RV infections depend on the gut microbiota19,21 and on secretor status, while the gut microbiota is also simultaneously dependent on secretor status. Previous studies reported that the non-secretor phenotype was associated with a lower intestinal microbial diversity17,23,24. A study also showed differences in microbiota between homozygote secretors (FUT2+/+) and heterozygote secretors (FUT2+/−)18. Therefore, a dose effect of FUT2, as has already been described for NoV attachment25, cannot be excluded. In our study, differences in the microbiota could be established, although in contrast to these previous studies, no difference in microbial richness between secretor and non-secretor individuals was evidenced. A trend-like difference was only reported at the genus level for changes in microbial communities between FUT2 genotypes in a work by Wacklin et al.17. Similarly, our multivariate analysis at the OTU level did not show statistically significant differences between FUT2 genotypes although group clusters were clearly identified. A recently published study involving a large population also failed in finding an association of intestinal microbial composition with blood group (ABO) or secretor status26. In that study, however, other factors that could determine how FUT2 status interacts with the intestinal microbiota have to be considered, as the studied group was composed of female tweens with and average age of 61. Therefore, differences in physiology, diet, or activity level between different age groups may lead to microbiome composition differences that could mask an association with FUT226. Diet has been identified as a major factor influencing intestinal microbial composition27. Interactions of dietary factors that depend on the geographic origin of the studied individuals (Spain in our case and Finland, Germany, USA and UK in the previous studies17,18,26,28 with secretor status may explain the distinct contribution of FUT2 to the composition of the microbiota, as found in our study. In this sense, it has been shown that differences in intestinal microbial composition between wild-type and FUT2−/− mice with humanised microbiota are eliminated when the animals follow a diet deficient in polysaccharides24. Similar to this diet by phenotype (FUT2) effect on the microbiota, disease by secretor status effects on microbial composition have been reported for intestinal inflammatory diseases (i.e. Crohn disease28), when comparing healthy and diseased individuals. This suggests that FUT2 status may play a role in shaping the intestinal microbiome in certain diet and disease contexts.

Although the number of analysed subjects in our study (35 individuals) and the previous works (3918, 2417, and 1828 individuals and mice with humanised microbiota from a single donor24), with the exception of the mentioned female tweens study26, are low, FUT2 still emerges as a genetic factor modulating the intestinal microbiota. Notwithstanding, in addition to the limitation of the low number of samples, our study may present other weaknesses. Possible bias introduced by the use of antibiotics in the period prior to the last two months before sampling (our selection criteria) or by the smoking or food habits of the participants, cannot be excluded, since all they can impact the microbiota composition. The gender of volunteers (63% women, 37% men) may also act as a confounder, since male and female can display differences in microbiota composition29. However, we showed that there were no differences in microbiota richness and composition based on gender (Supplementary Figure S4). In addition, RV causes diarrhoea mostly in the young and in the present study only adults (average age of 38) were enrolled. Adults can also be infected by RV without symptoms, but studies with larger populations of infants, especially prospective studies with large cohorts are needed to obtain more robust results. Specifically, it will be necessary to establish the host-microbiota-viral susceptibility/protection relationship in the RV disease susceptible population (<5 years).

In spite of the exposed limitations, the inclusion of anti-NoV and anti-RV IgA levels in our analyses significantly explained the inter-individual variations in the gut microbial composition associated with FUT2 status (Fig. 3C). This susceptibility by phenotype effect on the microbiota reinforces the idea that the three factors are interconnected. Also, remarkable similarities were found between our study and previous works. In agreement with former reports, we identified specific microbiota associations according to secretor status. In the present study, members of Prevotellaceae were detected in greater numbers in non-secretors, and Prevotella OTUs and the Prevotella group have been previously associated with the non-secretor phenotype by 16S rDNA sequencing28 and FISH23, respectively. Similar to our results, members of the genus Bacteroides and the family Lachnospiraceae were more abundant in non-secretor mice with humanised microbiota24, and increased numbers of Bacteroidetes have also been linked to non-secretors in two human studies18,28. However, two Bacteroides species (B. plebeius and B. fragilis) were related to the secretor phenotype on a PCR-DGGE analysis17. These species are characterised as having relatively high numbers of enzymes (i.e. α-L-fucosidases and other glycosyl hydrolases30), so they can take nutritional advantage of the degradation of HBGA glycan structures. Two different factors may be involved in the modulation of the microbiota by the availability of fucosylated carbohydrates: (i) L-fucose can be used as a carbon source in some intestinal bacteria, promoting their growth, and (ii) fucosylated HBGAs can act as specific bacterial binding sites that promote attachment and persistence in the gut. These two factors may have a complex relationship, as carbohydrate cross-feeding is common in the intestine, where some bacteria may benefit from the degradation of HBGA-glycan structures by other members of the microbiota31. Furthermore, it has been established that the intestinal microbiota itself affects host intestinal glycosylation patterns32,33, including fucosylation.

Of note, we were able to establish correlations between different taxa and susceptibility to both NoV and RV (i.e., Ruminococcaceae). NoV and RV infectivity was negatively correlated with different OTUs of Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcaceae. Conversely, Akkermansia levels correlated to higher levels of anti-RV IgAs. The only species of this genus, A. muciniphila, possesses a remarkable capacity for feeding on host mucins34, and trends toward a lower relative abundance in non-secretors17. Our data showed that Akkermansia was not different between the FUT2 groups, but was more abundantly present in non-secretors compared to secretors (1.08% vs 0.95%, respectively). In this context, the intriguing lack of efficacy of RV oral vaccines (consisting of live-attenuated viruses) in low- versus high-income countries may be based on differences between the settings that impact the intestinal microbiota35. However, the role of different bacterial taxa in RV/NoV infectivity still remains elusive, and establishing causal effects is still not possible. In investigations on human NoV infections of B cells, Jones et al. showed that Enterobacter cloacae expressed H-type substances on their surface that promoted viral binding to target cells and allowed in vitro infectivity19, while Miura et al. identified HBGA-like substances from Enterobacter spp. that promote cellular attachment of NoV viral-like particles36. In contrast, recent results with a gnotobiotic pig model questioned the role of this bacterium, demonstrating that E. cloacae-colonised pigs antagonised human NoV (GII.4) infections, resulting in reduced viral shedding37.

Understanding the interactions between virus, host, and microbiota could open new avenues in personalised medicine. Many possibilities exist in this context, including the rational design of NoV or RV vaccine compositions/protocols based on specific interactions between viral strains/bacteria and the host genotype, or the implementation of dietary strategies (e.g., pre- or probiotics) that target specific bacterial groups, resulting in enhanced defences. In this regard, recent results have shown that the anti-NoV effect of vitamin A supplementation can be partly explained through microbiota modulation, which results in an increased number of Lactobacillus, leading to immunomodulatory effects mediated by IFN-β38. Altogether, the findings show that viral infectivity must be understood within a holistic framework, in which host genetic background, glycobiology, and gut microbiota cannot be separated from viruses and host cells.

Methods

Subjects and Sampling

A total of 35 Spanish volunteers with a mean age of 38.43 ± 9.14 years and normal weight (body mass index [BMI] = 23.59 ± 3.68 kg/m2) participated in this study (Table 1). No gastrointestinal disorders, use of medicines (including probiotics and antibiotics) in the last two months, or any other diseases or problems were reported by the participants, who were given oral and written instructions for the standardised collection of samples. Stool samples were collected and kept frozen at −20 °C until delivery to the laboratory. Saliva samples were collected in the morning (8–10 a.m.) to minimize the effects of the circadian rhythm. The participants were instructed not to smoke, eat, drink, or brush their teeth for 2 h before the saliva collection.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the volunteers.

| Gender % (Prevalence) | Age (years) (mean ± SD) | BMI kg/cm2 (mean ± SD) | Secretor positive % (Prevalence) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 37.15% (13/35) | 40.43 ± 7.34 | 26.25 ± 3.50 | 61.54% (8/13) |

| Female | 62.85% (22/35) | 37.10 ± 9.95 | 21.77 ± 2.52 | 86.36% (19/22) |

| Total | 100% (35/35) | 38.43 ± 9.14 | 23.59 ± 3.68 | 77.14% (27/35) |

Ethic statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the Atencion Primaria-Generalitat Valenciana (CEIC-APCV). We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

FUT2 genotyping

Host DNA was extracted from saliva samples using the JETQUICK Blood & cell culture DNA spin kit (Genomed) following the manufacturer instructions. The secretor status was investigated by genotyping the FUT2 gene by PCR-RFLP as described previously25.

Determination of anti-RV and anti-NoV titers in saliva samples

To determine salivary IgA titers to RV and NoV, microtiter plates were coated either with purified RV triple layered particles (TLPs)39 (2 μg/ml) from human Wa strain (G1P[8]) or with a mix of norovirus P particles from genotypes GI.1, GII.4 (VA386_1996 and Den Haag_2006b variants) and GII.9 produced as previously described40,41 at 1 μg/ml each, in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Negative controls wells were coated with BSA at 1 μg/ml in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer. Plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked for 1 h at 37 °C with PBS-T with 3% BSA. After blocking, plates were incubated in triplicate with saliva samples at a 1:100 dilution in PBS-T with 1% BSA for 1.5 h at 37 °C and NoV- and RV-specific IgAs were detected with a secondary anti-human IgA antibody conjugated with HRP (Sigma) at a 1:4,000 dilution in PBS-T with 1% BSA for 1 h at 37 °C. Wells were washed four times with PBS-T, and the bound antibody was detected by the addition of 50 μl of o-phenylenediamine (Sigma). The reaction was stopped at 10 min with 3 M H2SO4, and the absorbance was read at 492 nm (Multiskan FC spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific). Microtiter plates were simultaneously coated with a 1:1,000 dilution of saliva in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer and processed in the same way as above to obtain the total IgA content of each saliva sample. The OD492 of the negative controls (BSA) were subtracted to obtain the specific anti-RV or anti-NoV titer. The OD492 of the specific anti-RV or anti-NoV was divided by the OD492 of total IgA and multiplied by 100 to obtain the normalised specific salivary IgA titer for each virus. All measurements were taken within the lineal range of the instrument (OD492 from 0.05 to 1.5).

Fecal DNA extraction and 16S rDNA sequencing

Total DNA was isolated from the fecal pellets by using the MasterPure Complete DNA & RNA Purification Kit (Epicentre) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications, including a bead-beater step and enzyme incubation to increase DNA extraction. The specific DNA extraction protocol was described previously42. DNA concentration in samples was measured using a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and diluted to 5 ng/μL. The V3-V4 region of 16S rDNA gene was amplified by PCR using Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences following Illumina protocols. After 16S rDNA gene amplification, the mutiplexing step was performed using Nextera XT Index Kit. 1 μl of the PCR product was checked with a Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 chip and libraries were sequenced using a 2 × 300pb paired-end run (MiSeq Reagent kit v3) on a MiSeq-Illumina platform (FISABIO sequencing service, Valencia, Spain). To rule out and control for possible reagent contamination, reagents for DNA extraction and for PCR amplification were also sequenced as controls.

Bioinformatics and Statistical analysis

Quality assessment was performed by the use of prinseq-lite program43 applying following parameters: min_length: 50; trim_qual_right: 20; trim_qual_type: mean; trim_qual_window: 20. R1 and R2 from Illumina sequencing where joined using fastq-join from ea-tools suite44. Data were obtained using an ad-hoc pipeline written in RStatistics environment45 and data processing was performed using a QIIME pipeline (version 1.9.0)46. Chimeric sequences and sequences that could not be aligned were also removed from the data set. The clustered sequences were utilised to construct Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) tables with 97% identity and representative sequences were classified into the respective taxonomical level from phylum to genus based on the Greengenes 16S rRNA gene database. Sequences that could not be classified to domain level, or were classified as Cyanobacteria, were removed from the dataset as they likely represent ingested plant material. All communities were rarefied to 12,100 reads per sample to calculate bacterial diversity. Subsequently, alpha diversity indexes (Chao1 and Shannon) and beta diversity using UniFrac distance among samples and PERMANOVA47 was used to test significance. Calypso software version 5.2 (http://cgenome.net/calypso/) was used with data transformed by square root with total sum normalization for the statistical analysis, multivariate test and data mining. To assess the relationship between FUT2 genotypes and the microbiota at family, genus and OTU levels the ANOVA test was utilized. Pearson’s correlations between the levels of bacterial families and antibody levels were also calculated and plotted using Calypso software. Predictive functional analysis was performed using PICRUSt48 with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe)49 was used to detect unique biomarkers (LDA score > 3.0).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Rodríguez-Díaz, J. et al. Relevance of secretor status genotype and microbiota composition in susceptibility to rotavirus and norovirus infections in humans. Sci. Rep. 7, 45559; doi: 10.1038/srep45559 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO) grants RYC-2013-12442 and AGL2014-52996-C2-2-R to JRD. SVV was recipient of a PhD scholarship from Generalitat Valenciana (Vali+d program, ACIF/2016/437).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions J.R.D., J.B., V.M. and M.C.C. designed the research. J.R.D., I.G.M., S.V.V. and R.G.R. carried out the experiments. J.R.D., V.M. and M.C.C. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the text.

References

- Desselberger U. & Goodfellow I. Noroviruses: a global cause of acute gastroenteritis. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 14, 664–665, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70776-5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate J. E. et al. Remaining issues and challenges for rotavirus vaccine in preventing global childhood diarrheal morbidity and mortality. Expert review of vaccines 11, 211–220, doi: 10.1586/erv.11.184 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith L. et al. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nature medicine 9, 548–553, doi: 10.1038/nm860 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell G. E., Kindberg E., Larson G. & Svensson L. Susceptibility to winter vomiting disease: a sweet matter. Rev Med Virol 21, 370–382, doi: 10.1002/rmv.704 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M. & Jiang X. Norovirus-host interaction: multi-selections by human histo-blood group antigens. Trends in microbiology 19, 382–388, doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.05.007 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al. Rotavirus VP8*: phylogeny, host range, and interaction with histo-blood group antigens. Journal of virology 86, 9899–9910, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00979-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani S. et al. The VP8* domain of neonatal rotavirus strain G10P[11] binds to type II precursor glycans. Journal of virology 87, 7255–7264, doi: 10.1128/JVI.03518-12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X. et al. Rotavirus infection and histo-blood group antigens in the children hospitalized with diarrhea in China. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.06.007 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordgren J. et al. Both Lewis and secretor status mediate susceptibility to rotavirus infections in a rotavirus genotype-dependent manner. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 59, 1567–1573, doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu633 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D. C. et al. Epidemiologic Association Between FUT2 Secretor Status and Severe Rotavirus Gastroenteritis in Children in the United States. JAMA pediatrics 169, 1040–1045, doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2002 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbert-Marcille B. M. et al. A FUT2 gene common polymorphism determines resistance to rotavirus A of the P[8] genotype. J Infect Dis 209, 1227–1230, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit655 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaydin G., Nordgren J., Sharma S. & Hammarstrom L. Association of elevated rotavirus-specific antibody titers with HBGA secretor status in Swedish individuals: The FUT2 gene as a putative susceptibility determinant for infection. Virus research 211, 64–68, doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.10.005 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blottiere H. M., de Vos W. M., Ehrlich S. D. & Dore J. Human intestinal metagenomics: state of the art and future. Current opinion in microbiology 16, 232–239, doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.06.006 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailford L. E., Crost E. H., Kavanaugh D. & Juge N. Mucin glycan foraging in the human gut microbiome. Front Genet 6, 81, doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00081 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autieri S. M. et al. L-fucose stimulates utilization of D-ribose by Escherichia coli MG1655 DeltafucAO and E. coli Nissle 1917 DeltafucAO mutants in the mouse intestine and in M9 minimal medium. Infection and immunity 75, 5465–5475, doi: 10.1128/IAI.00822-07 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L. V., Xu J., Falk P. G., Midtvedt T. & Gordon J. I. A molecular sensor that allows a gut commensal to control its nutrient foundation in a competitive ecosystem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96, 9833–9838 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacklin P. et al. Faecal microbiota composition in adults is associated with the FUT2 gene determining the secretor status. PloS one 9, e94863, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094863 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong M. et al. Reprograming of gut microbiome energy metabolism by the FUT2 Crohn’s disease risk polymorphism. The ISME journal 8, 2193–2206, doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.64 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. K. et al. Enteric bacteria promote human and mouse norovirus infection of B cells. Science 346, 755–759, doi: 10.1126/science.1257147 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettayebi K. et al. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science 353, 1387–1393, doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5211 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama R., Chassaing B., Zhang B. & Gewirtz A. T. Antibiotic treatment suppresses rotavirus infection and enhances specific humoral immunity. J Infect Dis 210, 171–182, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu037 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M. M. et al. Antibody prevalence and titer to norovirus (genogroup II) correlate with secretor (FUT2) but not with ABO phenotype or Lewis (FUT3) genotype. J Infect Dis 194, 1422–1427, doi: JID36719 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H. et al. Secretor Status Is Strongly Associated with Microbial Alterations Observed during Pregnancy. PloS one 10, e0134623, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134623 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap P. C. et al. Genetically dictated change in host mucus carbohydrate landscape exerts a diet-dependent effect on the gut microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 17059–17064, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306070110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marionneau S., Airaud F., Bovin N. V., Le Pendu J. & Ruvoen-Clouet N. Influence of the combined ABO, FUT2, and FUT3 polymorphism on susceptibility to Norwalk virus attachment. J Infect Dis 192, 1071–1077, doi: JID33851 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport E. R. et al. ABO antigen and secretor statuses are not associated with gut microbiota composition in 1,500 twins. BMC genomics 17, 941, doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3290-1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenburg J. L. & Backhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535, 56–64, doi: 10.1038/nature18846 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch P. et al. Colonic mucosa-associated microbiota is influenced by an interaction of Crohn disease and FUT2 (Secretor) genotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 19030–19035, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106408108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T. & Schloss P. D. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature 509, 357–360, doi: 10.1038/nature13178 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehemann J. H., Kelly A. G., Pudlo N. A., Martens E. C. & Boraston A. B. Bacteria of the human gut microbiome catabolize red seaweed glycans with carbohydrate-active enzyme updates from extrinsic microbes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 19786–19791, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211002109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn D. W. & Koropatkin N. M. Polysaccharide Degradation by the Intestinal Microbiota and Its Influence on Human Health and Disease. Journal of molecular biology 428, 3230–3252, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.06.021 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas M., Axelsson L. G., Cayuela C., Midtvedt T. & Trugnan G. Indigenous microbes and their soluble factors differentially modulate intestinal glycosylation steps in vivo. Use of a “lectin assay” to survey in vivo glycosylation changes. Histochem Cell Biol 124, 423–433, doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0004-1 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bry L., Falk P. G., Midtvedt T. & Gordon J. I. A model of host-microbial interactions in an open mammalian ecosystem. Science 273, 1380–1383 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Passel M. W. et al. The genome of Akkermansia muciniphila, a dedicated intestinal mucin degrader, and its use in exploring intestinal metagenomes. PloS one 6, e16876, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016876 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E. & Desselberger U. Correlates of protection against human rotavirus disease and the factors influencing protection in low-income settings. Mucosal immunology 8, 1–17, doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.114 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T. et al. Histo-blood group antigen-like substances of human enteric bacteria as specific adsorbents for human noroviruses. J Virol 87, 9441–9451, doi: JVI.01060-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S. et al. Enterobacter cloacae inhibits human norovirus infectivity in gnotobiotic pigs. Scientific reports 6, 25017, doi: 10.1038/srep25017 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. & Ko G. Antiviral effect of vitamin A on norovirus infection via modulation of the gut microbiome. Sci Rep 6, 25835, doi: 10.1038/srep25835 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Diaz J., Montava R., Garcia-Diaz A. & Buesa J. Humoral immune response to rotavirus NSP4 enterotoxin in Spanish children. J Med Virol 77, 317–322, doi: 10.1002/jmv.20450 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Vicente N. et al. Characterization of a novel conformational GII.4 norovirus epitope: Implications in norovirus-host interactions. J Virol, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01023-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-del-Campo A. et al. Noroviral p-particles as an in vitro model to assess the interactions of noroviruses with probiotics. PLoS One 9, e89586, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089586 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boix-Amoros A., Collado M. C. & Mira A. Relationship between Milk Microbiota, Bacterial Load, Macronutrients, and Human Cells during Lactation. Frontiers in microbiology 7, 492, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00492 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder R. & Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 27, 863–864, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronesty E. Command-line tools for processing biological sequencing data. ea-utils: FASTQ processing utilities, http://code.google.com/p/ea-utils (2011).

- Team R. C. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2012).

- Caporaso J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods 7, 335–336, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. In Austral Ecology 26.1 32–46 (2001).

- Langille M. G. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nature biotechnology 31, 814–821, doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome biology 12, R60, doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.