Abstract

Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to investigate how patterns of skin-to-skin care might impact infant early cognitive and communication performance.

Design

This was a retrospective cohort study.

Setting

This study took place in a level-IV all-referral neonatal intensive care unit in the Midwest USA specialising in the care of extremely preterm infants.

Participants

Data were collected from the electronic medical records of all extremely preterm infants (gestational age <27 weeks) admitted to the unit during 2010–2011 and who completed 6-month and 12-month developmental assessments in the follow-up clinic (n=97).

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included the cognitive and communication subscales of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III); and skin-to-skin patterns including: total hours of maternal and paternal participation throughout hospitalisation, total duration in weeks and frequency (hours per week).

Analysis

Extracted data were analysed through a multistep process of logistic regressions, t-tests, χ2 tests and Fisher's exact tests followed with exploratory network analysis using novel visual analytic software.

Results

Infants who received above the sample median in total hours, weekly frequency and total hours from mothers and fathers of skin-to-skin care were more likely to score ≥80 on the cognitive and communication scales of the Bayley-III. However, the results were not statistically significant (p>0.05). Mothers provided the majority of skin-to-skin care with a sharp decline at 30 weeks corrected age, regardless of when extremely preterm infants were admitted. Additional exploratory network analysis suggests that medical and skin-to-skin factors play a parallel, non-synergistic role in contributing to early cognitive and communication performance as assessed through the Bayley-III.

Conclusions

This study suggests an association between early and frequent skin-to-skin care with extremely preterm infants and early cognitive and communication performance.

Keywords: extreme prematurity, NEONATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Identifies natural, emergent patterns of skin-to-skin care with extremely preterm infants to reflect authentic human engagement experiences.

Uses the evidence to suggest ways to target specific intervention areas for increasing skin-to-skin care.

Supports current literature on the longer term benefits of skin-to-skin care.

Uses one instrument to assess early cognitive and communication performance.

Uses retrospective data which exclude variables known to impact neonatal neurodevelopment.

Introduction

The birth and subsequent hospitalisation of an extremely preterm infant is a trauma event. Unlike term infants, extremely preterm infants (infants born at <27 weeks) spend the last trimester of their gestation ex utero, in an artificial, technology-laden neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) that places them at a developmental disadvantage. Monitors, tubing and wires often create an environment that makes it difficult for authentic positive human interaction. In response, skin-to-skin care (SSC) has been incorporated into many NICUs across the world to re-establish this positive human contact.

SSC is the practice of holding an infant upright on a parent's chest in a manner that provides maximum bare skin ventral contact. The practice impacts infant physiological stability, stress and sleep as well as maternal stress and parenting behaviour. SSC studies over the last 25 years1–15 have collectively translated into a global acknowledgement that SSC is medically safe and significantly affects longer term neurodevelopmental cognitive, social and emotional outcomes.16–22

Despite the benefits of SSC, it is often difficult to engage some families in the practice. Findings from one of the most recent and comprehensive systematic reviews of the barriers and promoters of SSC (included in the complete package known as Kangaroo Mother Care)23 identified over 35 factors involved in integrating SSC into the NICU environment. The top three barriers to SSC were issues with the NICU physical facility, negative impressions by the staff about the practice and fear of injuring the infant during SSC. In contrast, SSC increased when mothers felt attached to their infants, felt confident in their parenting role and received support from family, friends or other mothers. While current studies, such as those found in the systematic review, can help in the design of new interventions promoting SSC, many are a reflection of participating in a highly supported and scrutinised form of SSC rather than parent practice as it naturally occurs in the NICU.

What remains unknown is how parents are actually engaging in the practice of SSC in an all-referral NICU setting in the USA when they are not involved in an SSC study. A rigorous study of routine SSC across a cohort of extremely preterm infants could identify specific strategies and intervention points for care providers to target their efforts at increasing parental engagement in SSC. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to identify the naturalistic patterns of SSC that parents engage in with their extremely preterm infants in an all-referral NICU and investigate how these patterns impact early infant cognitive and communicative performance. A secondary aim was to compare the relative effects of amount and intensity of SSC on these outcomes.

Patients and methods

This study was a retrospective cohort study of all infants admitted to the Small Baby Intensive Care Unit (SBICU) at Nationwide Children's Hospital (NCH) between 1 January 2010 and 30 November 2011. The SBICU is a specialised level-IV all-referral unit staffed by a centralised team of nurses who provide protocol-driven care23–25 to neonates born at a gestational age (GA) <27 completed weeks. These protocols, organised within the Small Baby Guidelines, outline how to specifically address the medical and developmental needs of extremely preterm infants. SSC is specifically designated as a critical practice for medical stability and neurodevelopmental outcomes and is described as a care piece that should be strongly encouraged whenever possible, as long as possible. All patients cared for in this unit are outborn and are transported to the SBICU for care of complications of prematurity including necrotising enterocolitis, sepsis, surgical issues, brain injury and so on.

Data

Retrospective data were extracted from the electronic medical record within three categories: (a) medical (b) SSC and (c) cognitive and communication outcomes at follow-up. Medical record information extracted for each patient included gender, GA, birth weight (BW), length of hospital stay (LOS), occurrence or absence of intraventricular haemorrhage in the brain (IVH), number of days on a ventilator (IPPV days), days until first full feed by mouth (PO DOL), whether the patient was a twin, triplet, etc (multiple births), and whether the patient received antenatal steroids. These variables were selected based on the outcome trajectories calculator developed by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network.26 Total hours of SSC for each parent were recorded for each day after the baby was admitted to the NICU until discharge. Hours were documented by the nursing staff in the patient medical record. (Audits performed comparing parental report and nurse report of SSC time indicated 89% consistency.) Summary measures of SSC use included total hours of SSC, the number of days between the day of admission and the first onset of SSC, total hours of SSC performed by the mother and father, intensity of SSC (average days of SSC per week) and whether the family participated in SSC after their child reached 33 weeks corrected age, a critical period of auditory development.27 To reduce the number of tested associations and aid in clinical interpretation, families were further classified as having a ‘high’ level of SSC participation if they were above the median in total hours, total hours for mother and total hours for father, and frequency of SSC (ie, above the median for each of the four variables). The remaining families were classified as having a ‘low’ level of SSC participation.

Cognitive and communication early performance outcomes were determined through the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III), a valid and reliable developmental assessment tool that is widely used in neonatal follow-up. Assessments were performed at 6 and 12 months by licensed professionals certified and trained in the tool28 and scores were adjusted for prematurity. Descriptive classifications were used according to the protocol outlined by Pearson Clinical with infants scoring <80 being described as ‘Borderline’ for developmental disability.29 Consequently, scores were treated as continuous variables and as dichotomised variables of scores <80 and scores ≥80.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was divided into three parts to address the clinical questions of interest. First, since the study is observational in nature, patterns of SSC participation (‘high’ vs ‘low’, as defined in the ‘Data’ section) were investigated graphically and associations between SSC measures and medical factors were tested. These associations were considered to explore for potential factors associated with SSC participation and to account for potential confounding of SSC with these other clinical/medical variables. A logistic regression model was fit to contrast the probability of being a high versus low SSC participant (as defined in the ‘Data’ section) as a function of gender, GA, BW, IVH, IPPV days, PO DOL, multiple births and receipt of antenatal steroids. Backwards elimination was used to select a final explanatory model based on minimising the Akaike's information criteria. Second, the association between SSC participation (high vs low) and Bayley-III scores was evaluated. Strength of association between raw Bayley scores and SSC participation (high vs low) was quantified and tested using point biserial correlations (rpb, tested against a null that the correlation was zero). Bayley scores dichotomised at the borderline disability level (<80 vs ≥80) were tested for association with SSC participation using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Associations between dichotomised Bayley scores and SSC participation were additionally adjusted for confounding based on the medical factors found to be associated with SSC participation.

Patterns between medical factors and SSC became evident and patterns of SSC and the Bayley-III scores became evident. Consequently, for the final analysis, we used our StickWRLD visual analytic software30 31 to investigate potential triangulations among specific aspects of medical factors, SSC and the Bayley-III scores. All factors were loaded into the StickWRLD visual framework and initial two-node association patterns were set with an initial residual value32 of 0.2. Subsequent analyses were performed incrementally at lower residual values to identify and compare associative relationships and to search for significant emerging triangular data patterns. Analyses concluded when the model reached a threshold residual value corresponding to visual associative overload.

Results

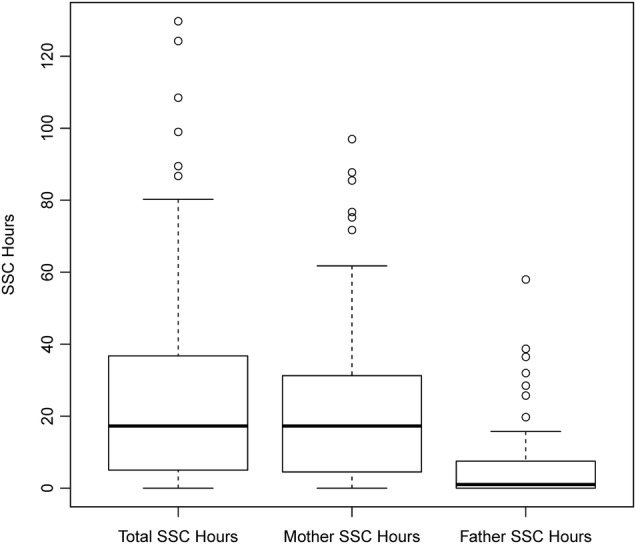

A total of 97 NICU patients were included in the study. The GA ranged from 22 to 26 weeks with an overall median of 25 weeks. Summary statistics of SSC usage (overall participation, participation by parent, SSC intensity and onset of SSC) are given in table 1. Mothers represented the majority of overall SSC participation, as evidenced by figure 1. Nine families were missing information on some aspect of SSC involvement. Among the remaining 88 families, 30 (34%) were classified as ‘high’ participants in SSC (above the median for total SSC hours, hours per parent and SSC intensity) while the other 58 (66%) were classified as ‘low’ participation in SSC.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of skin-to-skin care (SSC) from admission to 40 weeks postmenstrual age

| SSC Metric | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Min, max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total SSC (hours) | 27.4 (29.8) | 17.2 (5.1, 36.6) | 0, 129.8 |

| Mother SSC (hours) | 22.8 (22.4) | 17.2 (4.6, 30.9) | 0, 97 |

| Father SSC (hours) | 5.8 (10.4) | 1 (0, 7.5) | 0, 58 |

| SSC frequency (days/week) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.3, 3.2) | 0, 5 |

| SSC onset (days) | 6.2 (7.4) | 4 (1.8, 8) | 0, 45 |

IQR (25th centile, 75th centile).

Figure 1.

Overall and parent-specific SSC participation: boxplots displaying the distribution of overall SSC participation and by parent. Thick horizontal lines give medians while boxes display the middle 50% of the data (25th and 75th centiles). Whiskers extend to no more than 1.5 times the IQR (IQR= difference between 75th and 25th centiles) from the edge of the box. Points beyond the whiskers represent outliers. SSC, skin-to-skin care.

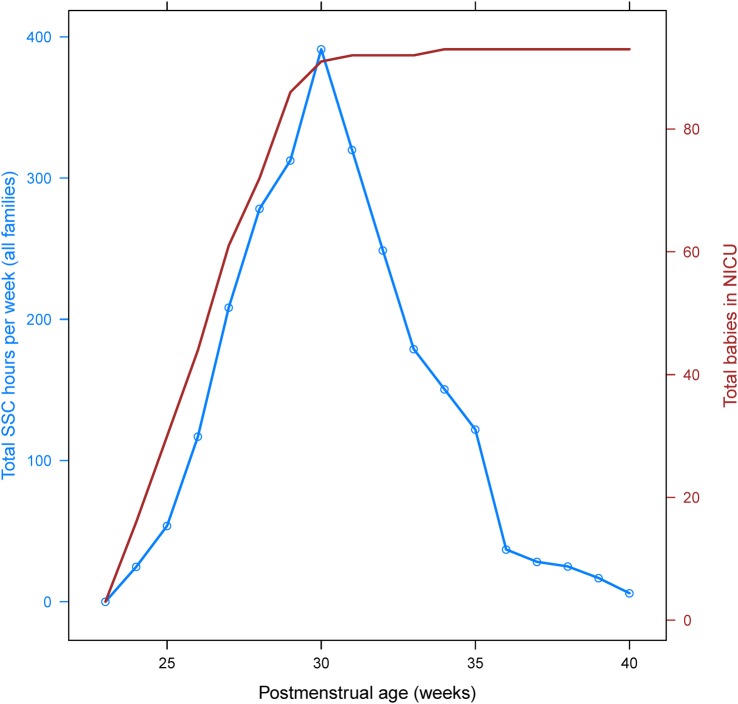

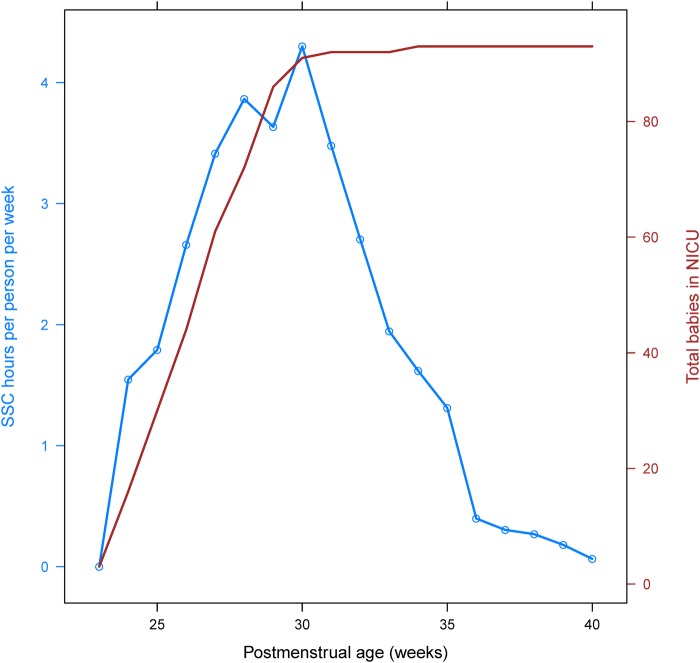

Patterns of intensity and total hours of SSC participation between the postmenstrual ages of 23 and 40 weeks are displayed on a study-wide (total person-hours per week, figure 2) and family (hours per family per week, figure 3) basis. There was a steady increase in total hours and hours per family until about 30 weeks, after which there was a corresponding precipitous decline until 40 weeks. Differences in medical factors between families with high versus low SSC participation are given in table 2. Receipt of antenatal steroids was the only significant (p<0.05) finding, with 71% of children from families with high SSC participation receiving antenatal steroids and 91% of children with low family SSC participation receiving them.

Figure 2.

Total SSC hours per week. Blue line displays the total number of SSC hours per week for all families in the study, by postmenstrual age. Red line gives the total number of babies in the NICU for the given week. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; SSC, skin-to-skin care.

Figure 3.

SSC intensity (hours per week per family). Blue line displays the average SSC intensity (hours per family per week) by postmenstrual age. Red line gives the total number of babies in the NICU for the given week. NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; SSC, skin-to-skin care.

Table 2.

Medical factors influencing skin-to-skin patterns

| Medical factors (categorical) | SSC low | SSC high | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 23 (0.4) | 8 (0.27) | 0.25 |

| Male | 35 (0.6) | 22 (0.73) | |

| Multiple births | |||

| No | 39 (0.67) | 18 (0.60) | 0.64 |

| Yes | 19 (0.33) | 12 (0.40) | |

| Antenatal steroids | |||

| No | 5 (0.09) | 8 (0.29) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 53 (0.91) | 20 (0.71) | |

| IVH | |||

| No | 28 (0.48) | 10 (0.33) | 0.26 |

| Yes | 30 (0.52) | 20 (0.67) | |

| Medical factors (continuous) | |||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 24.9 (1) | 24.4 (1.1) | 0.06 |

| Birth weight (g) | 748.2 (164.5) | 719.6 (188.5) | 0.48 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 117.6 (46.1) | 127.8 (40) | 0.28 |

| Days on ventilator | 41.6 (28.6) | 45 (33.2) | 0.63 |

| PO DOL (days) | 106.1 (35.9) | 117.7 (44.6) | 0.26 |

Numbers in each cell are mean (SD) for continuous and N (%) for categorical.

p Value for categorical based on χ2, for continuous based on t-test.

IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; PO DOL, days until first full feed by mouth; SSC, skin-to-skin care.

These factors (minus LOS, which was omitted because infants with longer LOS might be expected to have longer total SSC duration) were subsequently used to build a model to analyse the variance in SSC participation based on logistic regression with backwards elimination. The resulting model included antenatal steroids, BW and IVH as predictors (table 3). We investigated various cut-points for dichotomising BW and found the 75th centile to provide the best fit. Receipt of antenatal steroids (OR=0.136) and BW in the top quartile (OR=0.152) were associated with reduced odds of high SSC participation, while presence of IVH was associated with increased odds (OR=1.92).

Table 3.

ORs for high participation in skin-to-skin care (SSC) based on medical factors

| Univariable |

Multivariable |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Levels | High SSC | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Antenatal steroids | Yes | 20/73 (27%) | 4.16 | 1.06 to 18.2 | 0.024 | 7.36 | 1.67 to 32.53 | 0.008 |

| No | 8/13 (62%) | |||||||

| Birth weight | 844+ | 5/24 (21%) | 2.41 | 0.74 to 9.35 | 0.13 | 6.59 | 1.46 to 29.84 | 0.014 |

| <844 | 25/64 (39%) | |||||||

| IVH | Yes | 20/50 (40%) | 0.54 | 0.19 to 1.46 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.19 to 1.43 | 0.2 |

| No | 10/38 (26%) | |||||||

IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage.

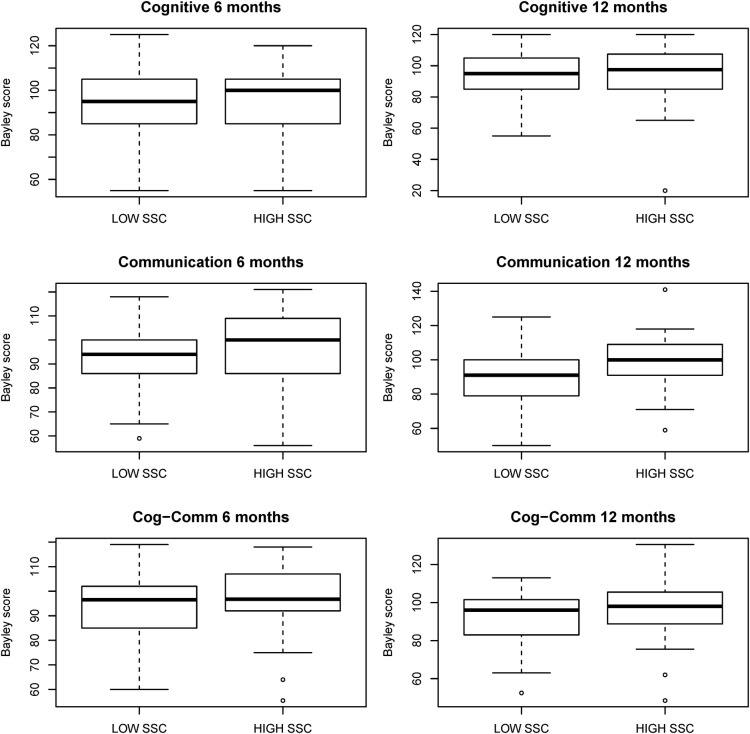

Next, association between SSC participation and cognitive and communication outcomes (Bayley scores) at follow-up were investigated. Figure 4 displays boxplots of the Bayley scores stratified by high and low SSC participation, while table 4 gives mean values for each examination by participation group. Communication scores at 12 months were somewhat higher in the high SSC group (p=0.05). We then dichotomised the Bayley score at the borderline disability level (<80 vs ≥80). Table 5 displays the number and percentage of patients that fall below this borderline disability level along with univariate ORs. To account for potential confounding, ORs were further adjusted by fitting a multivariable model including the factors identified to be associated with SSC participation (BW, antenatal steroids and IVH, table 5). None of the associations (except for cognitive examination at 6 months) reached statistical significance. However, there was a relatively consistent OR of 2 for associations between each dichotomised Bayley score and SSC participation in the multivariable models. Adjusted ORs were higher than the unadjusted because SSC participation was associated with factors that were also generally associated with lower Bayley scores.

Figure 4.

Bayley Cognitive and Communication Scores by SSC participation: boxplots displaying the distribution of Bayley cognitive, communication and combined cognitive–communication (Cog–Comm) scores at 6 and 12 months by SSC participation (high vs low). High SSC participation was defined as having above the median participation for total SSC hours, mother SSC hours, father SSC hours and SSC intensity (see text for details). Thick horizontal lines give medians while boxes display the middle 50% of the data (25th and 75th centiles). Whiskers extend to no more than 1.5 times the IQR (IQR= difference between 75th and 25th centiles) from the edge of the box. Points beyond the whiskers represent outliers.

Table 4.

Point biserial correlations (rpb) between low and high participation in skin-to-skin care (SSC) and Bayley-III cognitive and communication outcomes

| Bayley-III assessment | SSC low* | SSC High* | rpb | p Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive 6 months | 92.7 (15.7) | 96.3 (15.1) | 0.11 | 0.30 |

| Cognitive 12 months | 93.1 (14.6) | 93.9 (19.2) | 0.03 | 0.82 |

| Communication 6 months | 93.1 (12.9) | 96.9 (16.6) | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| Communication 12 months | 90.7 (15.4) | 98.2 (16.4) | 0.23 | 0.05 |

| Composite (cog/comm) 6 months | 92.9 (12.6) | 96.6 (14.4) | 0.13 | 0.21 |

| Composite (cog/comm) 12 months | 91.9 (13.6) | 96.1 (16.1) | 0.14 | 0.22 |

*Numbers in each cell are mean (SD).

†p Values are from test that point biserial correlations are different from zero.

Cog/comm, cognitive/communication.

Table 5.

Associations between low and high participation in skin-to-skin care (SSC) and borderline disability (<80 vs ≥80) Bayley-III cognitive and communication outcomes

| Per cent borderline developmental disability |

Univariable | Multivariable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayley examination | Low SSC | High SSC | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Cognitive 6 months | 11/58 (19%) | 2/30 (7%) | 3.28 | (0.92 to 11.67) | 0.07 | 4.46 | (1.08 to 18.41) | 0.04 |

| Cognitive 12 months | 8/49 (16%) | 2/28 (7%) | 2.54 | (0.66 to 9.77) | 0.18 | 2.87 | (0.62, 13.26) | 0.18 |

| Communication 6 months | 9/58 (16%) | 4/30 (13%) | 1.19 | (0.52 to 2.72) | 0.67 | 1.72 | (0.64 to 4.61) | 0.28 |

| Communication 12 months | 13/49 (27%) | 5/29 (17%) | 1.73 | (0.88 to 3.42) | 0.11 | 2.00 | (0.87 to 4.57) | 0.10 |

| Composite (cog/comm) 6 months | 8/58 (14%) | 3/30 (10%) | 1.44 | (0.52 to 3.95) | 0.48 | 2.22 | (0.68 to 7.28) | 0.19 |

| Composite (cog/comm) 12 months | 8/49 (16%) | 3/28 (11%) | 1.63 | (0.58 to 4.53) | 0.35 | 2.22 | (0.66 to 7.44) | 0.20 |

Multivariable models include antenatal steroids, birth weight and intraventricular haemorrhage.

Cog/comm, cognitive/communication.

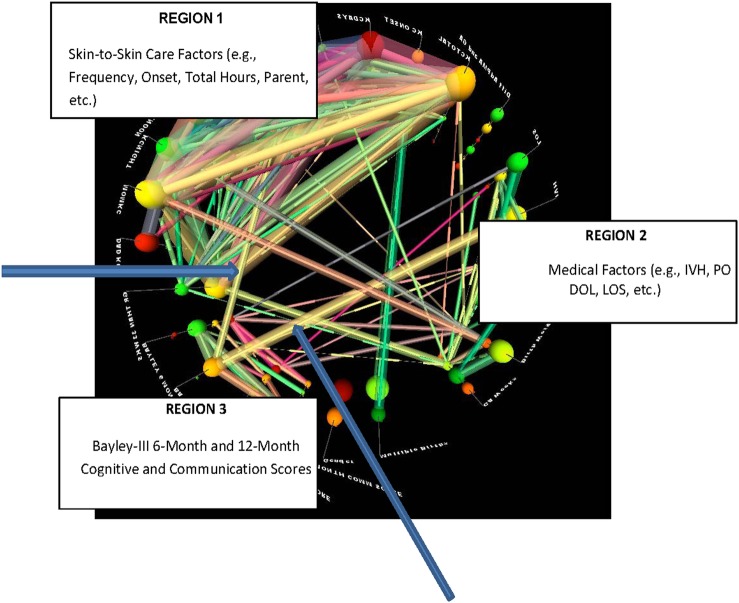

A final exploratory analysis of the data set was performed using StickWRLD software to identify possible emergent interactive network associations among SSC measures, medical factors and Bayley-III scores. Network displays (figure 5) indicated separate, but convergent significant associations between SSC measures and medical factors and the 12-month Bayley-III cognitive scores.

Figure 5.

Visual analytical display from StickWRLD software. The visual space is divided into three main regions: medical factors, skin-to-skin factors and Bayley-III Scores. Each line represents a significant correlation between factors with stronger correlations represented by lines that are thicker in diameter. Line colours are assigned randomly and are used only to aid in visual comparisons of associations. Within-region correlations are evident and expected. Two blue arrows indicate two unexpected strong correlations (one from each region) that converge on the Bayley-III 12-Month Cognitive Score, suggesting skin-to-skin Care frequency and presence or absence of intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) as parallel, but non-interactive factors impacting the score.

Discussion

Engagement in SSC with extremely preterm infants in the NICU varies among families. However, SSC patterns are evident in this population and potentially have an impact on early cognitive and communication performance. These findings are not new in that numerous studies11–22 have been devoted to the short-term and long-term developmental benefits of SSC. What is initially novel about our findings is that we have found a strong indication that SSC before 30 weeks postmenstrual age may play a role in the cognitive and communication development of extremely preterm infants. The period of time before 32 weeks is often considered a developmentally marginal time period in communication and language development. Underlying brain structure and auditory/visual development are not at full capacity33 and preterm infants are not yet prepared to vocalise or discern formal speech sounds.34 35 However, studies in neurobiology indicate that social development does occur during this time36–39 and could possibly represent an early foundational stage in the developmental continuum of communication and language.

A second novel finding is that extremely preterm infants, who had higher BWs, had received antenatal steroids and who did not have IVH, were at decreased odds of receiving a ‘high’ level of SSC (where high level was defined as above the median for total hours, frequency and hours for each parent). One possible explanation is that infants who were perceived as being ‘less sick’ were at reduced odds of receiving a high level of SSC. This poses questions about how medical caregivers and parents perceive the practice of SSC and how developmental information is being communicated between parents and the medical team.

Finally, our findings identify a concerning gap in SSC from 30 weeks corrected age to term age. Numerous studies highlight the essential nature of this time period for appropriate neurodevelopment.40–44 However, extremely preterm infants, who represent one of the highest risk categories for neurodevelopmental disability, are not receiving an SSC intervention shown to improve neurodevelopment at a fundamental time point of their developmental trajectory. This elicits additional questions about why parents choose to stop at this corrected age, the underlying mechanisms of communication development in this population and the potential added dimensional role of SSC as a communication intervention in the NICU.

One important limitation of our study is that it is retrospective in nature within an all-referral hospital system in the USA, which impedes our ability to capture and analyse additional factors shown to impact neonatal neurodevelopment. Consequently, we could not explore the effects of maternal health, socioeconomic status or education, which are shown to significantly influence neonatal developmental outcome. However, the intent of our study was to investigate if patterns of parental skin-to-skin behaviour should be considered in the overall discussion of mesosystemic variables contributing to longer term outcomes.

The study is also limited by sample size and possible confounding, which is inherently an issue when investigating associations. However as noted previously, NICU patients receiving SSC were actually associated with medical factors that were in turn associated with lower early-stage cognitive and communication scores. The study is also based on patients from a single hospital, and may not generalise to other neonatal units, especially because our unit is a level-4 all-referral unit with high-acuity infants and geographically distant parents. While we did see a relatively consistent pattern of association (c.f. table 5) between high/low SSC participation and the Bayley-III Cognitive and Communication Outcomes dichotomised at borderline disability (<80 vs ≥80), we reiterate that none of these associations achieved statistical significance and thus can only be viewed as suggestive results in need of confirmatory analysis. If the observed associations were to hold in the population along with the same level of SSC participation and prevalence of borderline disability, then roughly 460 total subjects would be needed to achieve 80% power to detect the association in a larger study.

Our research suggests that developmental investigation into very early time points in the life of extremely preterm infants that incorporates medical and behavioural components is warranted and critical to understanding how to fully optimise future developmental social and cognitive processes. Further prospective studies, involving more comprehensive measures and analyses of the early developmental NICU environment (22–40 weeks postmenstrual age), could help inform new designs for developmental caregiving and promotion of SSC throughout the duration of hospitalisation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Leif Nelin and the Small Baby Program for their continual advocacy and advancement towards the highest standard of developmentally appropriate care of extremely preterm infants.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. JG and GB designed and conducted the study, analysed the biostatistical portion, and wrote and reviewed manuscript drafts. JG, WCR and RWR performed visual analytics, wrote sections of the manuscript, and reviewed and refined manuscript drafts.

Funding: This project was supported by award number UL1TR001070 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nationwide Children's Hospital (IRB#13-00042) as an expedited study that meets the criteria for waiver of authorisation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are stored on our internal, high-security server. De-identified data set is available on request.

References

- 1.Colonna F, Uxa F, da Graca AM et al. . The “kangaroo-mother” method: evaluation of an alternative model for care of low birth weight newborns in developing countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1990;31:335–9. 10.1016/0020-7292(90)90911-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Leeuw R, Colin EM, Dunnebier EA et al. . Physiological effects of kangaroo care in very small preterm infants. Biol Neonate 1991;59:149–55. 10.1159/000243337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludington-Hoe SM, Thompson C, Swinth J et al. . Kangaroo care: research results, and practice implications and guidelines. Neonatal Netw 1994;13:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer K, Uhrig C, Sperling P et al. . Body temperatures and oxygen consumption during skin-to-skin (kangaroo) care in stable preterm infants weighing less than 1500 grams. J Pediatric 1997;130:240–4. 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70349-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Intervention programs for premature infants. How and do they affect development? Clin Perinatol 1998;25: 613–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tornhage CJ, Stuge E, Lindberg T et al. . First week kangaroo care in sick very preterm infants. Acta Paediatr 1999;88:1402–4. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb01059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohgi S, Fukuda M, Moriuchi H et al. . Comparison of kangaroo care and standard care: behavioral organization, development, and temperament in healthy, low-birth-weight infants through 1 year. J Perinatol 2002;22:374–9. 10.1038/sj.jp.7210749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludington-Hoe SM, Ferreira C, Swinth J et al. . Safe criteria and procedure for kangaroo care with intubated preterm infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2003;32:579–88. 10.1177/0884217503257618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begum EA, Bonno M, Ohtani N et al. . Cerebral oxygenation responses during kangaroo care in low birth weight infants. BMC Pediatr 2008;8:51 10.1186/1471-2431-8-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neu M, Robinson J. Maternal holding of preterm infants during the early weeks after birth and dyad interaction at six months. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010;39:401–14. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01152.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Diaz-Rossello J. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;3:CD002771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludington-Hoe SM. Thirty years of kangaroo care science and practice. Neonatal Netw 2011;30:357–62. 10.1891/0730-0832.30.5.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaffashi F, Scher MS, Ludington-Hoe SM et al. . An analysis of the kangaroo care intervention using neonatal EEG complexity: a preliminary study. Clin Neurophysiol 2013;124:238–46. 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conde-Agudelo A, Diaz-Rossello J. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD002771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mörelius E, Örtenstrand A, Theodorsson E et al. . A randomized trial of continuous skin-to-skin contact after preterm birth and the effects on salivary cortisol, parental stress, depression, and breastfeeding. Early Hum Dev 2015;91:63–70. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boundy EO, Dastjerdi R, Spegelman D et al. . Kangaroo mother care and neonatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137 http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flacking R, Lehtnonen L, Thomson G et al. . Closeness and separation in neonatal intensive care. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:1032–7. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02787.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman R, Rosenthal Z, Eidelman AI. Maternal-preterm skin-to-skin contact enhances child physiologic organization and cognitive control across the first 10 years of life. Biol Psychiatry 2014;75:56–64. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts KL, Paynter C, McEwan B. A comparison of kangaroo mother care and conventional cuddling care. Neonatal Netw 2000;19:31–5. 10.1891/0730-0832.19.4.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rojas MA, Kaplan M, Quevedo M et al. . Somatic growth of preterm infants during skin-to-skin care versus traditional holding: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2003;24:163–8. 10.1097/00004703-200306000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider C, Charpak N, Ruiz-Peláez JG et al. . Cerebral motor function in very premature-at-birth adolescents: a brain stimulation exploration of kangaroo mother care effects. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:1045–53. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scher MS, Ludington-Hoe S, Kaffashi F et al. . Neurophysiologic assessment of brain maturation after an 8-week trial of skin-to-skin contact on preterm infants. Clin Neurophysiol 2009;120:1812–18. 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seidman G, Unnikrishnan S, Kenny E et al. . Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care practice: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0125643 10.1371/journal.pone.0125643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nankervis CA, Martin EM, Crane ML et al. . Implementation of a multidisciplinary guideline-driven approach to the care of the extremely premature infant improved hospital outcomes. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:188–93. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shepherd E, Calvert T, Martin E et al. . Outcomes of extremely premature infants admitted to a children's hospital depends on referring hospital. J Neonat Perinat Med 2011;4:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, Tyson JE et al. . Outcome trajectories in extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics 2012;130: e115–25. 10.1542/peds.2011-3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahon E, Wintermark P, Lahav A. Auditory brain development in premature infants: the importance of early Experience. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1252:17–24. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06445.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Follow-up program. 2013; Retrieved from https://neonatal.rti.org/about/fu_background.cfm

- 29.Pearson Education. Bayley scales of infant development.3rd edn Pearson Clinical; 2008. Training. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray WC. MAVL and StickWRLD: visually exploring relationships in nucleic acid sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rumpf RW, Gonya J, Ray W. Visual hypothesis and correlation discovery for precision medicine. AMIA workshop on visual analytics in healthcare conference paper 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray WC, Wolock SL, Li N et al. . StickWRLD: Interactive visualization of massive parallel contingency data for personalized analysis to facilitate precision medicine. Proceedings of the 3rd annual Workshop on Visual Analytics in Healthcare, in conjunction with the American Medical Informatics Symposium. 2013; November. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Key APF, Lambert EW, Aschner JL et al. . Influence of gestational age and postnatal age on speech sound processing in NICU infants. Psychophys 2012;49:720–31. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01353.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caskey M, Stephens B, Tucker R et al. . Importance of parent talk on the development of preterm infant vocalizations. Pediatrics 2011;128:910–16. 10.1542/peds.2011-0609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caskey M, Stephens B, Tucker R et al. . Adult talk in the NICU with preterm infants and developmental outcomes. Pediatrics 2014;133:578–84. 10.1542/peds.2013-0104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva MG, Barros MC, Pessoa UM et al. . Kangaroo-mother care method and neurobehavior of preterm infants. Early Hum Dev 2016;95:55–9. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care) accelerates autonomic and neurobehavioural maturation in preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol 2003;45:274–81. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2003.tb00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldman R, Eidelman AI, Sirota et al. . Comparison of skin-to-skin (kangaroo) and traditional care: parenting outcomes and preterm infant development. Pediatrics 2002;110:16–26. 10.1542/peds.110.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman R. From biological rhythms to social rhythms: physiological precursors of mother-infant synchrony. Dev Psychol 2006;42:175–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reissland N, Kisilevsky BS, eds. Fetal development: research on brain and behavior, environmental influences, and emerging technologies. Switzerland: Springer International, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomason ME, Grove L, Lozon TA et al. . Age related increases in long-range connectivity in fetal functional neural connectivity networks in utero. Developmental Cog Neurosci 2015;11:96–104. 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krueger C, Garvan C. Emergence and retention of learning in early fetal development. Infant Behavior and Dev 2014;37:162–73. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson J, Tarabulsy GM, Bussieres E. Foetal programming and cortisol secretion in early childhood: a metal-analysis of different programming variables. Infant Behavior and Dev 2015;40:204–15. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harding R, Bocking AD, eds. Fetal growth and development. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]