Abstract

Background

Bloodstream infections are often associated with significant mortality and morbidity. We aimed to investigate changes in the epidemiology of bloodstream infections in Switzerland between 2008 and 2014.

Methods

Data on bloodstream infections were obtained from the Swiss antibiotic resistance surveillance system (ANRESIS).

Results

The incidence of bloodstream infections increased throughout the study period, especially among elderly patients and those receiving care in emergency departments and university hospitals. Escherichia coli was the predominant pathogen, with Enterococci exhibiting the most prominent increase over the study period.

Conclusions

The described trends may impact morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs associated with bloodstream infections.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We performed a retrospective analysis of bloodstream infections in Switzerland.

We analysed data from ANRESIS, a large national bloodstream infection database (Swiss centre for antibiotic resistance surveillance).

Twenty-six acute Swiss hospitals were included.

No data on mortality was included.

Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The influence of multiple factors, such as the increases in longevity and comorbidities and the use of more invasive technologies,1 could lead to secular changes in the epidemiology of BSIs.

Only few nationwide studies have focused on the incidence of BSIs, and their results were often inconsistent. A study from England described an increasing incidence of BSIs until 2006, followed by decline between 2006 and 2008.1 A significant decrease in BSIs was also observed in a Danish population-based study which included data until 2008.2 On the other hand, a report from Finland showed an increase in episodes of BSI until 2007,3 and a European surveillance study from the EARS-Net suggested an increase of the burden of BSI until 2008 based on trends of the five major bacterial pathogens.4 To the best of our knowledge, recent analyses of population-based studies have not been published. The present work aims to describe temporal trends in BSI incidence between 2008 and 2014 in Switzerland, using the national surveillance system.

Methods

Data on BSIs were obtained from the Swiss centre for antibiotic resistance surveillance (ANRESIS). Since 2004, the ANRESIS programme has collected all routine microbiological data from a representative group of microbiology laboratories located across Switzerland, with blood culture surveillance introduced in 2006. Each participating laboratory sends bacteraemia results on a regular basis to a central database located at the Institute for Infectious Diseases in Bern, Switzerland. We restricted the data set to acute care hospitals that continuously reported ≥5 BSIs per year without major fluctuations from 2008 through 2014. Unfortunately, not all hospitals send negative blood culture results to the central database. The analysed data set represents approximately one-third (26 hospitals) of all acute care hospitals in Switzerland5 with institutions being evenly distributed across the country.

Positive blood cultures were grouped as episodes of BSI if they occurred in a 7-day time window for a given patient. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) and other typical skin commensals (see online supplementary appendix) were considered as an infection if identified in >1 blood culture, or in one blood culture and a catheter tip within the same episode; otherwise they were considered as contaminants and excluded from the analysis. A BSI was considered polymicrobial if different microbial species were identified during the same episode. For a more detailed trend analysis, the following microorganisms groups were selected: Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, non-E. coli Enterobacteriaceae, polymicrobial BSI, CoNS and Enterococcus spp. A subanalysis of the following categories was performed: department (outpatient, emergency or other department vs other), age (<65 vs ≥65 years), gender (male vs female) and type of hospital (community hospital vs university hospital).

bmjopen-2016-013665supp_appendix.pdf (274.9KB, pdf)

Incidence rates were based on the number of reported bacteraemia isolates per 100 000 population. Since our data are from ∼33% of the acute care hospital beds in Switzerland, we attempted to forecast the incidence in the total population by simple linear extrapolation, based on population statistics.5 6 This assumes both that the community is uniformly served by the available beds, and that the 33% is a representative sample of the secondary and tertiary care infrastructures.5 We investigated the latter in the context of a simple sensitivity analysis, whereby the split of 50%:50% primary to tertiary care beds present in our sample data was altered to reflect that in the whole country (80%:20%). Despite being rather crude in nature, the simple change in proportions provides the most straightforward method for investigating plausible differences in the population as a whole.

Unadjusted models for the mean increase in bacteraemia per year were fitted using generalised linear models with Poisson distribution and loglink function, using an offset for the sample population estimate in the appropriate year.

Adjusted models were investigated by including gender, age (above or below 65 years), microorganism group (6 groups), hospital type (community or university), hospital department (outpatient, emergency or otherwise) and number of contaminants as covariates.

Poisson goodness of fit was tested using the χ2 test. Overdispersion was investigated using the likelihood ratio test with subsequent fitting of a negative binomial model, if appropriate.

A significance level of 5% was used with p values determined using Wald-type statistics and 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were performed in R.

Results

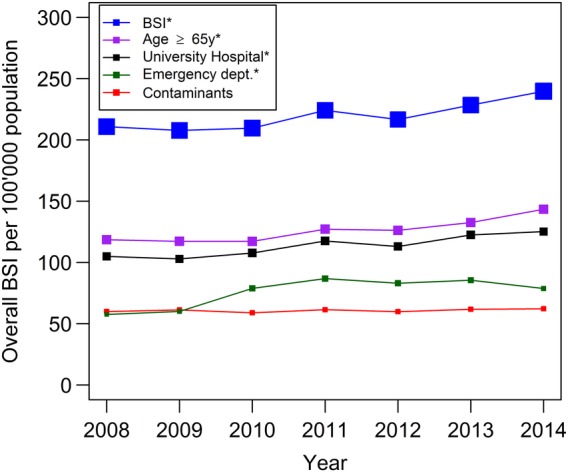

A total of 40 378 BSIs were reported between 2008 and 2014, with a mean incidence rate of 220 episodes per 100 000 population. The incidence rate increased by 14%, from 211 in 2008 to 240 per 100 000 population in 2014 (p<0.001, figure 1), while contaminant episodes (not included in the following analysis) remained constant over this period. The sensitivity analysis described above revealed lower incidence rates of BSI (from 174 in 2008 to 197 per 100 000 population in 2014), but the same 14% increase for this period (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Incidence in bloodstream infections 2008–2014: trends overall and for subgroups. Note: *significant increase (p<0.001). BSI, bloodstream infection; dept, department.

In adjusted models, among the patients with BSI, we observed an increase in number of BSIs in individuals ≥65 years (from 119 to 144 episodes per 100 000 population, mean increase of 3.0% per year, p<0.001). A supplementary analysis eliminating the bias of population growth in the specific at-risk population also revealed an increase in the incidence (from 705 in 2008 to 796 per 100 000, p<0.001) in older people (≥65 years). An additional analysis for lower ages did not indicate any significant trends (refer to the online supplementary appendix table A). We observed a significant increase of BSI diagnosed in emergency departments (from 58 to 79 per 100 000 population, +5.2% per year, p<0.001) and in university hospitals (from 105 to 125 per 100 000 population, +2.8% per year, p<0.001).

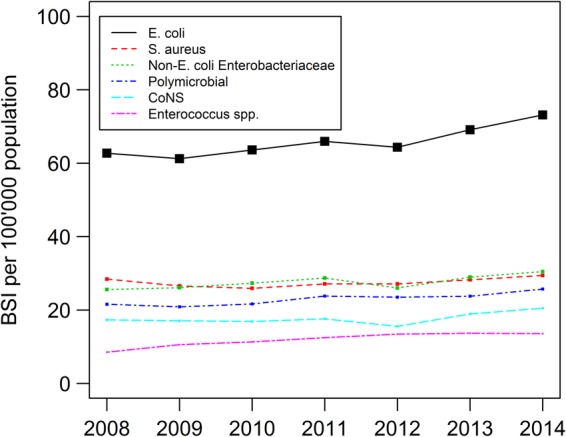

In 2014, E. coli was the most frequently detected microorganism (73 per 100 000 population, 30.5% of all episodes). Seventy per cent of all BSIs were caused by E. coli, S. aureus, polymicrobial BSI, CoNS, non-E. coli Enterobacteriaceae or Enterococci. All microorganism groups exhibited an increasing trend (figure 2), although this was only marginal for S. aureus (from 28 to 29 per 100 000, p=0.05). Enterococci displayed a steeper relative trend than other pathogens (from 9 to 14 per 100 000 population, +8.4% per year, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Incidence of BSIs caused by E. coli, S. aureus, non-E. coli Enterobacteriaceae, polymicrobial episodes, CoNS and Enterococcus spp. Note: all trends were statistically significant (S. aureus p=0.05, rest p<0.001). BSI, bloodstream infection; CoNS, coagulase-negative Staphylococci; E. coli, Escherichia coli; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, no national studies on recent BSI trends have been published in the past few years.1 2 4 In this nationwide BSI surveillance study, we observed a 14% increase in BSI incidence in Switzerland between 2008 and 2014. Published European data from before 2008 show variable trends, with increasing bacteraemia rates in Finland from 2004 to 20073 and England from 2004 to 20061 but decreasing rates in England from 2006 to 20081 and Denmark from 2000 to 2008.2 Overall, the increase in BSI was more prominent in emergency departments. This could be due to a decreasing average duration of hospitalisation7 with discharge of sicker patients who are prone to readmission, for example, in case of surgical wound infection. This phenomenon appeared to be more pronounced in elderly people, even after adjusting for changes in the longevity of the underlying population. An alternative explanation could be the increasing number of immigrants6 who tend to seek medical help not in private practices, but in emergency departments, where blood cultures are drawn more liberally. Moreover, as previously observed,8 we cannot rule out an upward trend in healthcare-associated infections overall or subtle changes in blood culture ordering practice leading to improved diagnosis of BSI.

The absolute BSI incidence rate observed in our study was higher than that reported in the majority of population-based studies1 3 9 with the exception of a report from Denmark.2 As shown in the sensitivity analysis, our main analysis overestimated the incidence rate due to an over-representation of university hospitals in the data set. It has been described before that BSI incidence rates are higher in university compared with community hospitals,10 and indeed, following correction for hospital type, incidence rates were comparable to the aforementioned population-based studies.

As expected,9 E. coli presents as the most important cause of bacteraemia in Switzerland. Our data also revealed increasing incidences of E. coli and non-E. coli Enterobacteriaceae over time, as observed in England between 2004 and 2008.1 This trend could be explained by several factors. BSIs were increasingly detected in emergency departments, a marker for infections acquired in the community, and in older people, who are known to be at higher risk for E. coli BSI.11 12

Moreover, while the incidence of S. aureus bacteraemia remained stable over time, the marked upward trend in BSIs caused by Enterococci is of particular concern, since they may be associated with higher mortality.13 We were unable to identify a predisposing factor for the increase in enterococcal BSIs. However, an association with intensive care unit departments and vulnerable patients with frequent exposure to the healthcare system is conceivable.13 14

Our study has several limitations. First, we extrapolated incidence based on the epidemiology of only 33% of all Swiss acute hospitals and, consequently, the generalisability of our findings may be somewhat limited. A simple sensitivity analysis reflecting the actual percentage split between university and community hospitals did not reveal any significant differences. Even considering this, the study does not include BSIs diagnosed in long-term care facilities and by general practice physicians. The second potential limitation is that we considered an episode as being polymicrobial if multiple microorganisms were isolated within 1 week, which could influence the BSI incidence estimates. The lack of a widely accepted definition for what constitutes polymicrobial BSI complicates the evaluation of its incidence. Finally, no reliable information regarding the total number of drawn blood cultures is available in the ANRESIS database. Unfortunately, not all hospitals send negative blood culture results to the central laboratories and we are therefore unable to present the total number of blood cultures taken.

In conclusion, in this extrapolated Swiss population-based study we describe an increase in BSIs between 2008 and 2014, especially in those detected in emergency room patients. The role of E. coli continues to become more prominent, while Enterococci showed the greatest increase over the study period. The described trends may impact morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs associated with BSI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all microbiology laboratories participating in the ANRESIS network: Institute for Laboratory Medicine, Cantonal Hospital Aarau; Central Laboratory, Microbiology Section, Cantonal Hospital Baden; Clinical Microbiology, University Hospital Basel; Viollier AG, Basel; Laboratory Medicine EOLAB, Department of Microbiology, Bellinzona; Institute for Infectious Diseases, University Bern; Microbiology Laboratory, Unilabs, Coppet; Central Laboratory, Cantonal Hospital Graubünden; Microbiology Laboratory, Hospital Thurgau; Microbiology Laboratory Hôpital Fribourgeois, Fribourg; Bacteriology Laboratory, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva; ADMED Microbiology, La Chaux-de-Fonds; Institute for Microbiology, Université de Lausanne; Centre for Laboratory Medicine, Cantonal Hospital Luzern; Centre for Laboratory Medicine, Cantonal Hospital Schaffhausen; Centre for Laboratory Medicine Dr Risch, Schaan; Central Institute, Hôpitaux Valaisans (ICHV), Sitten; Centre of Laboratory Medicine St Gallen; Institute for Medical Microbiology, University Hospital Zürich; Laboratory for Infectious Diseases, University Children's Hospital Zürich. The authors also thank the steering committee of ANRESIS. They thank Paolo Mombelli for his editorial support.

Footnotes

Collaborators: R Auckenthaler, Synlab Suisse, Switzerland; A Cherkaoui, Bacteriology Laboratory, Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland; V Gaia, Department of Microbiology, EOLAB, Bellinzona, Switzerland; O Dubuis, Viollier AG, Basel, Switzerland; A Egli, Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland; D Koch, Federal Office of Public Health, Bern, Switzerland; AK, Institute for Infectious Diseases, University of Bern, Switzerland; S Leib, Institute for Infectious Diseases, University of Bern, Switzerland; S Luyet, Swiss Conference of the Cantonal Ministers of Public Health, Switzerland; P Nordmann, Molecular and Medical Microbiology, Department of Medicine, University Fribourg, Switzerland; V Perreten, Institute of Veterinary Bacteriology, University of Bern, Switzerland; J-C Piffaretti, Interlifescience, Massagno, Switzerland; G Prod'hom, Institute of Microbiology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland; J Schrenzel, Bacteriology Laboratory, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland; AF Widmer, Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, University of Basel, Switzerland; G Zanetti, Service of Hospital Preventive Medicine, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland; R Zbinden, Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Zürich, Switzerland.

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study. NB and AA analysed the data. NB, JM and AK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. All authors commented and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: The ANRESIS database is funded by the Federal office of Public Health, the Conference of cantonal health ministers and the University of Bern, Switzerland.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: the Swiss Centre for Antibiotic Resistance (ANRESIS), R Auckenthaler, A Cherkaoui, V Gaia, O Dubuis, A Egli, D Koch, S Leib, S Luyet, P Nordmann, V Perreten, J-C Piffaretti, G Prod'hom, J Schrenzel, AF Widmer, G Zanetti, and R Zbinden

References

- 1.Wilson J, Elgohari S, Livermore DM et al. Trends among pathogens reported as causing bacteraemia in England, 2004-2008. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17:451–8. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen SL, Pedersen C, Jensen TG et al. Decreasing incidence rates of bacteremia: a 9-year population-based study. J Infect 2014;69:51–9. 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skogberg K, Lyytikäinen O, Ollgren J et al. Population-based burden of bloodstream infections in Finland. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18:E170–6. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Kraker ME, Jarlier V, Monen JC et al. The changing epidemiology of bacteraemias in Europe: trends from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013;19:860–8. 10.1111/1469-0691.12028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG), (Federal Office of Public Health), Spitalstatistiken. (Hospital statistics) 2014. http://www.bag.admin.ch/index.html.

- 6.2015. Bundesamt für Statistik, (Federal Office of statistics), migration und integration. http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index.html.

- 7.Hospital statistics 2015. http://www.hplus.ch/de/zahlen_fakten/h_spital_und_klinik_monitor/akutsomatik (accessed 11 Jun 2016).

- 8.Lai CC, Chen YH, Lin SH et al. Changing aetiology of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections at three medical centres in Taiwan, 2000-2011. Epidemiol Infect 2014;142:2180–5. 10.1017/S0950268813003166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laupland KB. Incidence of bloodstream infection: a review of population-based studies. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013;19:492–500. 10.1111/1469-0691.12144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez-Bano J, López-Prieto MD, Portillo MM et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of community-acquired, healthcare-associated and nosocomial bloodstream infections in tertiary-care and community hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:1408–13. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Mee-Marquet NL, Blanc DS, Gbaguidi-Haore H et al. Marked increase in incidence for bloodstream infections due to Escherichia coli, a side effect of previous antibiotic therapy in the elderly. Front Microbiol 2015;6:646 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchaim D, Zaidenstein R, Lazarovitch T et al. Epidemiology of bacteremia episodes in a single center: increase in Gram-negative isolates, antibiotics resistance, and patient age. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2008;27:1045–51. 10.1007/s10096-008-0545-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinholt M, Ostergaard C, Arpi M et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics and 30-day mortality of enterococcal bacteraemia in Denmark 2006-2009: a population-based cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20:145–51. 10.1111/1469-0691.12236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billington EO, Phang SH, Gregson DB et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes for Enterococcus spp. blood stream infections: a population-based study. Int J Infect Dis 2014;26:76–82. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013665supp_appendix.pdf (274.9KB, pdf)