Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the incidence of severe retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) requiring treatment and describe current treatment patterns in the UK.

Design

Nationwide population-based case ascertainment study via the British Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit and a national collaborative ROP special interest group. Practitioners completed a standardised case report form (CRF).

Setting

All paediatric ophthalmologists providing screening and/or treatment for retinopathy in the UK were invited to take part.

Participants

Any baby with ROP treated or referred for treatment between 1 December 2013 and 30 November 2014, treated with laser, cryotherapy, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor or vitrectomy/scleral buckling, or a combination.

Main outcome measure

Incidence of ROP requiring treatment.

Results

We received 370 CRFs; 327 were included. Denominator from epidemiological data: 8112 infants with birth weight of <1500 g. The incidence of ROP requiring treatment was 4% (327/8112, 95% CI 3.6% to 4.5%). Median gestational age was 25 weeks (IQR 24.3–26.1), and median birth weight 706 g (IQR 620–821). Median age at first treatment was 80 days (IQR 71–96). 204 right eyes (62.39%) had type 1 ROP, and 27 (8.26%) had aggressive posterior ROP. Infants were also treated for milder disease: 9 (2.75%) right eyes were treated for type 2 ROP, and 74 (22.63%) for disease milder than type 1 with plus or preplus, which we defined here as ‘type 2 plus’ disease. First-line treatment was diode laser photoablation of the avascular retina in 90.5% and injection of VEGF inhibitor in 8%.

Conclusions

ROP treatment incidence in the UK is 2.5 times higher than previously estimated. 8% of treated infants receive intravitreal VEGF inhibitor, currently unlicensed. Research is needed urgently to establish safety and efficacy of this approach. Earlier treatment and increasing numbers of surviving premature infants require an increase in appropriate eye care facilities and staff.

Trial registration number

Keywords: NEONATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

High case ascertainment using robust epidemiological methodology.

High-quality data, based on individual case reports from highly qualified specialists in paediatric ophthalmology.

High completion rate of reports.

Case ascertainment relying on practitioners notifying cases possibly led to small degree of under-reporting, affecting numerator of incidence estimate.

Epidemiological data for denominator (number of low-birthweight infants) not available for full area surveyed and in part extrapolated from reported data.

Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a potentially blinding condition typically affecting preterm neonates of low gestational age and low birth weight.1 ROP is a major cause of preventable blindness in children worldwide: of 15 million children born worldwide in 2010, an estimated 53 000 developed sight-threatening type ROP requiring treatment and 20 000 became blind or severely sight impaired.2 Two-thirds of children suffering sight loss from ROP live in middle-income and moderately developed countries, particularly Latin America.1 2 Incidence of blindness from ROP is lower in highly developed countries (3–13%), where risk factors such as oxygen supplementation and blood oxygen saturation are monitored meticulously, and minimal in poorly developed countries, where premature babies often do not survive.1 In highly and moderately developed countries, the incidence of ROP is increasing, as advances in neonatal management allow more premature infants to survive despite very low gestational age and birth weight.3 4

The current standard treatment for sight-threatening ROP is laser photoablation of the non-vascularised, immature retina. Treatment decisions are based on severity (stage 1–5 or an aggressive posterior form of the condition, aggressive posterior ROP (AP-ROP)) and location (zone 1–3) of the disease and retinal vascular changes (plus disease) as defined by the International Committee for the Classification of ROP.5 Early treatment is now recommended to avoid progression to sight-threatening complications; a clinical algorithm advocates treatment for ‘type 1’ or ‘high-risk prethreshold’ ROP, defined as ‘zone 1 stage 3 ROP with or without plus, or zone 1 stage 1/2 with plus, or zone 2 stage 2/3 with plus disease’.6 However, treatment is occasionally given for earlier forms of ROP, that is, ‘type 2’ or ‘low-risk prethreshold’ ROP (zone 1, stage 1 or 2 without plus, or zone 2, stage 3 without plus disease)6 and ‘mild ROP’ (milder than type 2).7

However, even with timely laser photocoagulation, ROP results in unfavourable structural and visual outcomes in a small, but significant number of children.6 8 9 It usually requires intubation and sedation or general anaesthesia, which may not be safe in systemically unstable infants, and it irreversibly destroys the peripheral retina, reducing the peripheral visual field.

Following the successes in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy, recombinant antibodies targeted against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), injected into the vitreous cavity, have recently been used in addition to laser photoablation and as first-line monotherapy to treat the most severe forms of ROP.10 Neither ranibizumab nor bevacizumab is licensed for this indication, though ranibizumab is licensed for intravitreal injection in AMD and few other retinal conditions. Despite being unlicensed,11 bevacizumab is in ophthalmic use, as it incurs only a fraction of the cost of ranibizumab while having equivalent efficacy.12

In ROP, reported benefits of VEGF inhibitors include fast regression of neovascularisation and plus disease, vascularisation of the peripheral retina and the lack of a need for general anaesthesia. However, local and systemic safety is unknown. In infants, VEGF is vital in directing the sequential and orderly development of blood vessels in the retina and systemically.13 14 After injection into the eye, these agents enter the systemic circulation, and there are concerns about dose and timing of administration and potential adverse events, ocular and systemic. Most studies reporting the use of VEGF inhibitors in ROP have used bevacizumab rather than ranibizumab, partly because the larger size of the molecule may make it less likely to induce systemic suppression of VEGF serum levels; there are, however, no pharmacokinetic data to support this concept.

The lack of central registries or databases for the treatment of ROP hampers the collection of information about current treatment patterns. To evaluate current practice patterns in the treatment of ROP in the UK, we set up a 1-year national surveillance project. The main objectives of this study are to determine the current incidence of ROP requiring treatment and current treatment preferences.

Methods

We conducted a prospective epidemiological active surveillance study of ROP treatment in the UK.

Study population

The UK ROP screening guideline recommends screening of infants <1501 g birth weight and <32 weeks gestational age.15

As denominator, we identified the number of premature births with birth weight of <1500 g in the surveyed area from the Office for National Statistics of England and Wales, http://www.statistics.org.uk. Scotland and Northern Ireland do not report on birth weight, so we estimated the number of low-birthweight (LBW) babies in these areas by assuming that the proportion of live births who were LBW was the same as that observed in England. The latest available birth figures from the Office for National Statistics show that in 2014, there were 661 496 live births in England and 33 544 in Wales; of these, respectively, 6987 and 322 had a birth weight of <1500 g. The number of live births in Northern Ireland and Scotland was 24 394 and 56 725, respectively, so assuming a similar proportion of LBW babies as observed in England, would have resulted in 258 and 545 babies, respectively. The total number of live births with birth weight <1500 g would then be 8112.

Inclusion criteria: any baby with ROP treated or referred to another unit for treatment between 1 December 2013 and 30 November 2014, with treatment either in the form of laser therapy, cryotherapy, VEGF inhibitor or vitrectomy/scleral buckling, or a combination of these treatments.

Exclusion criteria: any infant not fulfilling the above inclusion criteria.

Data collection

Incident cases were identified through the existing reporting system set up by the British Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (BOSU). From December 2013 to December 2014, BOSU mailed cards to all consultant ophthalmologists and associate specialists in the UK once a month, with an invitation to report new cases of treated ROP, defined as above. On receipt of case notifications, we mailed a standardised case report form (CRF) collecting clinical data to the reporting ophthalmologists. We also set up an electronic special interest group (SIG), through which clinicians could inform the research team directly of new cases and send completed CRFs.

Definition of ROP severity groups

The CRF asked clinicians to specify severity (stage) and location (zone) of ROP based on the International Classification of ROP (ICROP).5 6 We then categorised the data into levels of severity as defined in previous publications6 7 (table 1). However, not all possible scenarios of zone/stage/plus disease status are covered by these classifications. A particular problem is zone 3 disease with plus and zone 2 stage 1 with plus; we categorised these as ‘type 2 plus disease’, which is an addition to existing classifications. A second problem is that preplus disease was not yet defined at the time of the ICROP when type 1 and type 2 disease were described.6 As preplus disease is considered to carry a high risk of progression,16 and as close monitoring is recommended, we also categorised cases of preplus disease as ‘type 2 plus’, with the exception of zone 1 stage 3 disease, which should be treated regardless of plus disease status and is categorised as type 1 disease (table 1).

Table 1.

Severity of retinopathy classification

| Zone | Stage | Plus | Severity category | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP-ROP | 5 | |||

| 1 | 3 | No plus | Type 1 | 6 |

| 1 | 3 | Preplus | This study | |

| 1 | 3 | Plus disease | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | Plus disease | 6 | |

| 1 | 1 | Plus disease | 6 | |

| 2 | 3 | Plus disease | 6 | |

| 2 | 2 | Plus disease | 6 | |

| 2 | 1 | Plus disease | Type 2 plus | This study |

| 3 | 3 | Plus disease | ||

| 3 | 2 | Plus disease | ||

| 3 | 1 | Plus disease | ||

| 1 | 2 | Preplus | ||

| 1 | 1 | Preplus | ||

| 2 | 3 | Preplus | ||

| 2 | 2 | Preplus | ||

| 2 | 1 | Preplus | ||

| 3 | 3 | Preplus | ||

| 3 | 2 | Preplus | ||

| 3 | 1 | Preplus | ||

| 1 | 2 | No plus | Type 2 | 6 |

| 1 | 1 | No plus | ||

| 2 | 3 | No plus | ||

| 2 | 2 | No plus | Mild | 7 |

| 2 | 1 | No plus | ||

| 3 | 3 | No plus | 7 | |

| 3 | 2 | No plus | ||

| 3 | 1 | No plus | 7 | |

| 4 | Partial retinal detachment | 5 | ||

| 5 | Total retinal detachment | 5 |

AP-ROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity.

Confounders

We reviewed data to exclude duplication of cases arising from children being transferred between neonatal units or consultants, and from reports received via BOSU and via the SIG routes.

Statistical analysis

Data from the CRFs were entered onto an electronic Red Cap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database. A random sample of forms were inspected to ensure data quality. After data lock, data were transferred into Stata V.13.0 for analysis. Characteristics of infants requiring ROP treatment were summarised using means and SDs for approximately Gaussian continuous variables and medians and IQRs for non-Gaussian continuous variables. Categorical variables are reported as numbers and proportions.

Results

Participants—numerator: case ascertainment and inclusion

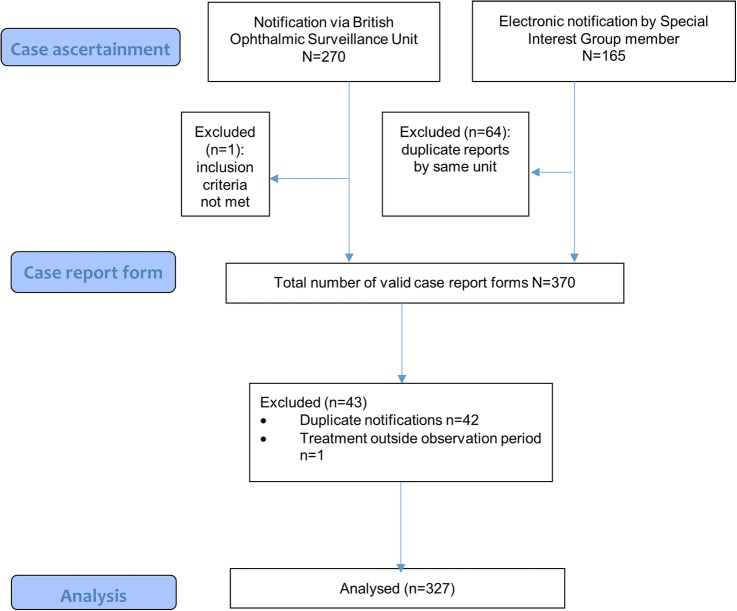

During the observation period, BOSU recorded a card return rate of 77.2%. Clinicians notified BOSU of 270 cases (figure 1). We asked clinicians to complete CRF for 268 babies, excluding one who did not meet the inclusion criteria. To reduce bias from under-reporting, we set up a UK ROP-SIG. Members share an electronic mailing list and can report cases of ROP treatment to the research team electronically; this route led to communication of 165 cases. In total, we received 370 completed forms. We excluded one, as treated outside the observation period, and 42 duplicate reports (same child, reported by different clinicians/units). We included 327 cases in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Case ascertainment, data collection and analysis flow chart (modified from CONSORT, www.consort-statement.org).

Treatment incidence

Based on the above, the incidence of treatment for ROP during the observation period was 327/8112 or 4% (95% CI 3.6% to 4.5%).

Patient characteristics

Of the included patients, 57.8% were male (table 2); 69.7% were white, 13.8% Asian, 5.5% black, 5.2% mixed and 5.8% other; and 72.8% were singletons, 24.5% twins and 2.1% triplets. Median (IQR) gestational age at birth was 25 weeks (24.3–26.1), and median (IQR) birth weight was 706 g (620–821). Median (IQR) age at first ROP treatment was 80 days (71–96).

Table 2.

Demographic, pregnancy and neonatal details of infants requiring ROP treatment

| Number identified | 327 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 138 (42.2%) |

| Male | 189 (57.8%) |

| Ethnic group | |

| Asian | 45 (13.8%) |

| Black | 18 (5.5%) |

| Mixed | 17 (5.2%) |

| Other | 19 (5.8%) |

| White | 228 (69.7%) |

| Single/multiple birth | |

| Singleton | 238 (72.8%) |

| Twin | 80 (24.5%) |

| Triplet | 7 (2.1%) |

| Other | 2 (0.6%) |

| Birth weight in g, median (IQR) | 706 (620–821) |

| Gestational age at birth in weeks, median (IQR) | 25 (24.3–26.1) |

| Age at first ROP treatment in days, median (IQR) | 80 (71–96) |

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Indications for treatment

In the following, we report figures for the right eye; figures for the left eye are similar. At first treatment, 204 right eyes (62.39%) had type 1 ROP, and 27 (8.26%) had AP-ROP (table 3). Type 2 plus ROP was present in 74 right eyes (22.63%), and type 2 in 9 (2.75%). Six (1.83%) had mild ROP. One infant had bilateral, and two had unilateral retinal detachments at first treatment (table 3).

Table 3.

Severity of retinopathy in right and left eyes on the day of first treatment

| Severity category | Number of right eyes treated (% of 327) | Number of left eyes treated (% of 327) | Same severity in both eyes (% of 327) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP-ROP | 27 (8.26) | 27 (8.26) | 27 (8.26) |

| Type 1 | 204 (62.39) | 202 (61.77) | 174 (53.21) |

| Type 2 plus | 74 (22.63) | 69 (21.10) | 43 (13.56) |

| Type 2 | 9 (2.75) | 9 (2.75) | 6 (1.83) |

| Mild | 6 (1.83) | 9 (2.75) | 2 (0.61) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.31) | 2 (0.61) | 0 |

| Partial retinal detachment | 1 (0.31) | 3 (0.92) | 1 (0.31) |

| Total retinal detachment | 0 | 0 | 0 |

AP-ROP, aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity.

Primary treatment

In 90.5% of right eyes, the first treatment administered was diode laser photoablation of the avascular retina (table 4). One eye received cryotherapy and laser combined (0.3%). Twenty-six infants (8%) received bilateral VEGF inhibitor injections as primary treatment. One child (0.3%) received laser in one and VEGF inhibitor injection in the other eye in the same treatment session, as a vitreous haemorrhage precluded the view of the retina in one eye. Data were missing for three right (0.9%) and six left eyes (1.8%).

Table 4.

Details of primary treatment

| First treatment n=327 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Right eye n (% of 327) |

Left eye n (% of 327) | Same treatment modality in both eyes n (% of 327) |

|

| Diode laser | 296 (90.5%) | 294 (89.9%) | 291 (89.0%) |

| VEGF inhibitor injection | 26 (8.0%) | 26 (8.0%) | 26 (8.0%) |

| Cryotherapy and laser | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | |

| VEGF inhibitor injection plus laser* | 1 (0.3% | 1 (0.3%) | 0 |

| Missing data | 3 (0.9%) | 6 (1.8%) | 1 (0.3%) |

*Infant who received VEGF inhibitor in one eye and laser treatment in the other in the same treatment session.

VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Discussion

We present the first systematic evaluation of ROP requiring treatment and current treatment preferences in the UK since the introduction of new treatment recommendations and since the first, unlicensed, use of VEGF inhibitors for this condition.

The primary objectives of this study were to estimate the current incidence of ROP requiring treatment in the UK and physicians' current preference for treatment modalities, including their use of VEGF inhibitors. Over a 12-month period, we identified 327 premature infants treated for ROP, of whom 90.5% received the current standard treatment, diode laser photoablation, and 8% received VEGF inhibitors. Using epidemiological figures of LBW infants in England and Wales and an estimate of this figure for Scotland and Northern Ireland, we calculated that the incidence of ROP treatment in infants born with birth weight under 1500 g is 4%.

The principal limitation of our study is the case ascertainment methodology, which informs the numerator in our calculation of treatment incidence. The BOSU active surveillance system relies on practitioners notifying a central research office of new cases and to complete CRFs. We sought to maximise case ascertainment by setting up a UK ROP-SIG to optimise stakeholder engagement. The BOSU card return rate (response rate) for the observation period was 77.2%. SIG provided notification of 165 cases. Most but not all of the cases notified via the SIG were formally reported by CRFs. Over the same period, the National Neonatal Audit Programme (NNAP), to which most neonatal units in England and Wales contribute, recorded 321 infants receiving treatment for ROP (personal communication, Daniel Grey, Data Analyst, NNAP). The geographic area covered by our study included England and Wales, and Scotland and Northern Ireland. We recorded 292 infants reported by units in England and Wales, 19 from Scotland and 16 from Northern Ireland. There are two possible explanations for the lower number of treatment cases in England and Wales we observed in comparison to NNAP: either our study delivered an underestimate, or NNAP data are an overestimate. During our study period, there was a 77.2% response rate to BOSU. It would seem plausible that cards were more often returned when babies were observed, but we have no evidence to support this. It is possible therefore that cases were omitted. However, our electronic SIG picked up babies who were not reported via the BOSU cards, so we believe that this would mitigate any under-reporting by BOSU. An alternative explanation for the discrepancy is that data entry onto the NNAP database by non-ophthalmic staff may erroneously have recorded ROP screening visits as ROP treatment episodes, leading to an overestimate of treatment numbers.

As denominator, we selected infants born with a birth weight of less than 1500 g. ROP screening criteria include a second item to define the infant at risk, that is, birth before 32 weeks gestational age.17 However, figures by gestational age are not routinely captured and so our denominator will have excluded the small number of babies who are born before 32 weeks but weigh more than 1500 g. This approach is consistent with other publications.18 Unfortunately, figures of infants with LBW are not reported throughout the area we surveyed, and we estimated the proportion of LBW infants in Scotland and Ireland from those reported for England.

Compared with previous reports, our study provides evidence of an increase in the number of infants treated for ROP in the UK and evidence of a change in treatment pattern. A previous BOSU study detected 223 preterm babies with stage 3 ROP over a 16-month period between 1 December 1997 and 31 March 1999 of whom just 59% were treated—76% of these with laser photocoagulation and 22% with cryotherapy.19 This study used a mixed methodology which included a parental survey, requiring individual consent for study participation. The authors suspected that this led to under-reporting of cases, and they did not present an incidence figure. A report from a single centre in Scotland observed that between 1995 and 2004, 5% of premature infants meeting the UK screening criteria required treatment.20 Two UK-based studies, which used large national databases of routinely collected data, NNAP and Hospital Episode Statistics,21 18 reported significantly lower incidences of ROP requiring treatment (1.5–2%) than our study (4%), probably due to under-reporting, as ophthalmologists were not involved in data collection.22 23 The strengths of our approach are high case ascertainment and data completion. Our treatment incidence figure is also comparable with reports from other countries, which report treatment of 1–5% of infants at risk.24–28

An initially surprising finding was that 27% of eyes received treatment for ROP milder than type 1 and AP-ROP, the current treatment threshold.17 6 8 9 However, the overwhelming majority of these had preplus disease, which we propose to categorise as ‘type 2 plus’ disease: 74 right and 69 left eyes (22.63% and 21.10%, respectively). In fact, previous reports indicate that 70% of those with preplus disease at 33–34 weeks gestational age may progress to requiring laser treatment.16 Treatment for disease earlier than type 1 is also not a phenomenon limited to our setting: a recent report of practice patterns of US-based ROP experts found that a substantial proportion of premature infants, 9.5%, were treated for ROP milder than type 1, as practitioners were concerned about as vascular dragging, tractional membranes, vitreous haemorrhages or persistent ROP, all of which are not captured by the current ICROP classification.7 Our study design did not collect this level of detailed information, but it is clear that in the UK, practitioners are concerned particularly about preplus disease, and provide early treatment.

Finally, our study identified 26 infants who received VEGF inhibitor injections as primary and only treatment, and one who received combined VEGF inhibitor and laser treatment. This is the first published national figure for this new treatment modality; it may inform the design of future ROP treatment trials. At present, the medium and longer term safety and efficacy of this approach, that is, risk of recurrence of ROP and effects on cognitive and physical development, are not known, although concerns about neurodevelopmental outcomes and late recurrence are emerging.29 30 Some authors advocate their use for zone 1 ROP or AP-ROP, or in cases of systemically unwell infants, poor visibility of the retina, or after failed laser photocoagulation.10 Research is urgently needed to provide information about safety and efficacy of these treatments, and to integrate them into current treatment algorithms.

The treatment incidence we report is likely to be generalisable to other highly developed countries, where facilities and staff are available to provide high-intensity care for infants born prematurely.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the British Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit, in particular, Mr Barny Foot, for advice on study design and collection of case notifications. We thank Ms Anneka Tailor for liaising with practitioners across the UK to facilitate data collection and completion of reports, and for maintaining the study database. We thank Mr Zabed Ahmed for setting up a comprehensive electronic database.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Members of the UK ROP Special Interest Group: Abbott Joseph, Aclimandos Wagih, Adams Gill, Al-Khaier Ayman, Allen Louise, Arashvan Kayvan, Ashworth Jane, Barampouti Faye, Barnes Jonathan, , Barrett Victoria, , Barry John Sebastian, Bates Adam, Berk Tulin, Biswas Susmito, Blaikie Andrew, Brennan Rosie, Bunting Howard, Butcher Jeremy, LB, Chan-Ling Tailoi, Chan Jonathan, Child Christopher, Choi Jessy, Clark David, Clark David, Clifford Luke, Dabbagh Ahmad, AHD-N, Dawidek Gervase, Dhir Luna, Drake Karen, Edwards Richard, Esakowitz Leonard, Escardo-Paton Julia, Evans Anthony, Fleck Brian, Geh Vernon, George Nick, Gnanaray Lawrence, Goyal Raina, Haigh Paul, Hancox Joanne, Haynes Richard, Heath Dominic, Henderson Robert, Hillier Roxane, Hingorani Melanie, Jain Saurabh, Jain Sunila, Jones David, Kafil-Hussain Namir, Kelly Simon, Kenawy Nihal, Kipioti Tina, Kulkarni Archana, Lavy Tim, Laws David, Lawson Joanna, Leitch Jane, Ling Roland, VL, Macrae Mary, Mahmood Usman, Markham Richard, Marr Jane, May Kristina, McLoone Eibhlin, Moosa Murad, Morton Claire, Mount Ali, Muen Wisam, Mulvihill Alan, Munshi Vineeta, Muqit Mahi, Murray Robert, Nair Ranjit, Newman William, O’Colmain Una, Patel Chetan, Patel Himanshu, Pedraza Luis Amaya, Pilling Rachel, Puvanachandra Narman, Quinn Anthony, Rathod Dinesh, AR, Reddy Ashwin, Rowlands Alison, Scotcher Stephen, Scott Christopher, Sekhri Rajnish, Shafiq Ayad, Sleep Tamsin, Tambe Katya, Tandon Anamika, Tappin Alison, Taylor Robert, Theodorou Maria, Thomas Shery, Thompson Graham, Tiffin Peter, Ullah Muhammed Aman, Watts Patrick, West Stephanie, West Stephanie, Whyte Iain, Wickham Louisa, Williams Cathy, Wong Chien, Wren Siobhan, Zakir Rahila

Contributors: All authors meet the ICMJE criteria and have completed the ICJME authorship form. GGWA, CB, LB, AHD-N, VL and AR developed the study protocol. LB, AHD-N, GGWA and CB secured funding. All authors reviewed and discussed and interpreted the data acquired. WX carried out data analysis. AHD-N drafted the manuscript, which was then critically reviewed and modified by all authors. All authors, external and internal, had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The lead author, AHDN, affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Funding: The study received funding from the Moorfields Special Trustees (grant ST 14 01 D) and the Birmingham Eye Foundation. The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare that this work was funded by Moorfields Eye Charity and the Birmingham Eye Foundation. There have not been any financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee North of Scotland, Aberdeen (13/NS/0059).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Abbott Joseph, Aclimandos Wagih, Adams Gill, Al-Khaier Ayman, Allen Louise, Arashvan Kayvan, Ashworth Jane, Barampouti Faye, Barnes Jonathan, Barrett Victoria, Barry John Sebastian, Bates Adam, Berk Tulin, Biswas Susmito, Blaikie Andrew, Brennan Rosie, Bunting Howard, Butcher Jeremy, Chan-Ling Tailoi, Chan Jonathan, Child Christopher, Choi Jessy, Clark David, Clark David, Clifford Luke, Dabbagh Ahmad, Dawidek Gervase, Dhir Luna, Drake Karen, Edwards Richard, Esakowitz Leonard, Escardo-Paton Julia, Evans Anthony, Fleck Brian, Geh Vernon, George Nick, Gnanaray Lawrence, Goyal Raina, Haigh Paul, Hancox Joanne, Haynes Richard, Heath Dominic, Henderson Robert, Hillier Roxane, Hingorani Melanie, Jain Saurabh, Jain Sunila, Jones David, Kafil-Hussain Namir, Kelly Simon, Kenawy Nihal, Kipioti Tina, Kulkarni Archana, Lavy Tim, Laws David, Lawson Joanna, Leitch Jane, Ling Roland, Macrae Mary, Mahmood Usman, Markham Richard, Marr Jane, May Kristina, McLoone Eibhlin, Moosa Murad, Morton Claire, Mount Ali, Muen Wisam, Mulvihill Alan, Munshi Vineeta, Muqit Mahi, Murray Robert, Nair Ranjit, Newman William, O’Colmain Una, Patel Chetan, Patel Himanshu, Pedraza Luis Amaya, Pilling Rachel, Puvanachandra Narman, Quinn Anthony, Rathod Dinesh, Reddy Ashwin, Rowlands Alison, Scotcher Stephen, Scott Christopher, Sekhri Rajnish, Shafiq Ayad, Sleep Tamsin, Tambe Katya, Tandon Anamika, Tappin Alison, Taylor Robert, Theodorou Maria, Thomas Shery, Thompson Graham, Tiffin Peter, Ullah Muhammed Aman, Watts Patrick, West Stephanie, West Stephanie, Whyte Iain, Wickham Louisa, Williams Cathy, Wong Chien, Wren Siobhan, and Zakir Rahila

References

- 1.Gilbert C, Muhit M. Twenty years of childhood blindness: what have we learnt? Community Eye Health 2008;21:46–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blencowe H, Lawn JE, Vazquez T et al. Preterm-associated visual impairment and estimates of retinopathy of prematurity at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res 2013;74(Suppl 1): 35–49. 10.1038/pr.2013.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert C, Fielder A, Gordillo L et al. Characteristics of infants with severe retinopathy of prematurity in countries with low, moderate, and high levels of development: implications for screening programs. Pediatrics 2005;115:e518–25. 10.1542/peds.2004-1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J et al. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the EPICure studies. BMJ 2012;345:e7961 10.1136/bmj.e7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of P. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:991–9. 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early Treatment For Retinopathy Of Prematurity Cooperative G. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:1684–94. 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta MP, Chan RV, Anzures R et al. Practice Patterns in Retinopathy of Prematurity Treatment for Disease Milder Than Recommended by Guidelines. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;163: 1–10. 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V et al. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics 2005;116:15–23. 10.1542/peds.2004-1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V et al. , Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative G. Final visual acuity results in the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Arch Ophthalmol 2010;128:663–71. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mintz-Hittner HA, Kennedy KA, Chuang AZ et al. Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab for stage 3+ retinopathy of prematurity. N Engl J Med 2011;364:603–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Bevacizumab (Avastin) for eye conditions: Report of findings from a workshop held at NICE on 13 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittenberg R, Hu B, Comas-Herrera A, et al. Care for older people: projected expenditure to 2022. on social care and continuing health care for England older population. Nuffield Trust in partnership with LSE PSSRU, London, UK. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/60887/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thebaud B. Angiogenesis in lung development, injury and repair: implications for chronic lung disease of prematurity. Neonatology 2007;91:291–7. 10.1159/000101344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenstein JM, Krum JM, Ruhrberg C. VEGF in the nervous system. Organogenesis 2010;6:107–14. 10.4161/org.6.2.11687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson AR, Haines L, Head K et al. UK retinopathy of prematurity guideline. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:2137–9. 10.1038/eye.2008.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace DK, Freedman SF, Hartnett ME et al. Predictive value of pre-plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:591–6. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson AR, Haines L, Head K et al. UK retinopathy of prematurity guideline. Early Hum Dev 2008;84:71–4. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Painter SL, Wilkinson AR, Desai P et al. Incidence and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity in England between 1990 and 2011: database study. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:807–11. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haines L, Fielder AR, Baker H et al. UK population based study of severe retinopathy of prematurity: screening, treatment, and outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005;90: F240–4. 10.1136/adc.2004.057570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhaliwal C, Fleck B, Wright E et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in Lothian, Scotland, from 1990 to 2004. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2008;93:F422–6. 10.1136/adc.2007.134791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong HS, Santhakumaran S, Statnikov Y et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in English neonatal units: a national population-based analysis using NHS operational data. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014;99:F196–202. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warden C, George J, Nithyanandarajah A et al. Inaccuracy of ROP screening data in National Neonatal Audit Programme report. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:237–8. 10.1038/eye.2013.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahlmann-Noor A, Bunce C, Adams G et al. Data accuracy in estimates of treatment incidence for retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;(3):CD004863. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bas AY, Koc E, Dilmen U. Incidence and severity of retinopathy of prematurity in Turkey. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:1311–4. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slidsborg C, Olesen HB, Jensen PK et al. Treatment for retinopathy of prematurity in Denmark in a ten-year period (1996 2005): is the incidence increasing? Pediatrics 2008;121:97–105. 10.1542/peds.2007-0644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmström GE, Hellstrom A, Jakobsson PG et al. Swedish national register for retinopathy of prematurity (SWEDROP) and the evaluation of screening in Sweden. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:1418–24. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmström G, Hellström A, Jakobsson P et al. Evaluation of new guidelines for ROP screening in Sweden using SWEDROP—a national quality register. Acta Ophthalmol 2015;93: 265–8. 10.1111/aos.12506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Sorge AJ, Termote JU, Simonsz HJ et al. Outcome and quality of screening in a nationwide survey on retinopathy of prematurity in The Netherlands. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:1056–60. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morin J, Luu TM, Superstein R et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Following Bevacizumab Injections for Retinopathy of Prematurity. Pediatrics 2016;137:pii: e20153218 10.1542/peds.2015-3218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mintz-Hittner HA, Geloneck MM, Chuang AZ. Clinical management of recurrent retinopathy of prematurity after intravitreal bevacizumab monotherapy. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1845–55. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]