Abstract

We report a rare complication in an immunosuppressed patient with IgA nephropathy who suffered from severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, severe capillary leakage and shock after placement of a double lumen central venous catheter. He could be successfully treated by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and therapeutic plasma exchange. This report highlights the severity of late-onset complications of catheter placements and shows the potential of ECMO treatment for the management of acute illnesses with bridge to recovery.

Background

Patients with acute kidney injury frequently require temporary central venous catheters for dialysis, preferentially placed in the internal jugular or, less advocated, the subclavian vein. Complications of temporary central venous catheters are not uncommon and include inadequate flow (7.6%), inadvertent catheter withdrawal (5.6%) and bacteraemia (5.1%).1 Severe complications, for example, traumatic perforation of the cardiac or the vessel wall, are only rarely observed but can occur days and weeks after catheter placement.2 Air embolism as a complication of dialysis catheter placement is only rarely described—possibly due to a publication bias—but can result in a detrimental clinical course.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is increasingly used in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting to improve extracorporeal gas exchange mainly in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)3–5 but also in patients pre and post heart and lung transplantation.6–9 Increasing experience with this technique also allows its use to manage acute illnesses such as myocarditis or drug intoxications by employing ECMO.10 11 Here, we report on a young patient who was treated with ECMO for acute respiratory failure and shock following removal of a central venous catheter which had been placed for immunoadsorption treatment of IgA nephropathy.

Case presentation

Initial presentation

A 20-year-old Caucasian male was transferred to the ICU of our tertiary care hospital due to severe ARDS (Horowitz index 58 mm Hg). The patient had been admitted to a smaller hospital 7 days earlier with deteriorating renal function due to IgA nephropathy (creatinine on admission 3.87 mg/dL, estimated glomerular filtration rate 21 mL/min). A renal biopsy showed necrotising intracapillary and extracapillary proliferating glomerulonephritis. A 15.5 F×15 cm double lumen dialysis catheter (Medcomp, Harleysville, Pennsylvania, USA) was placed in the right internal jugular vein without complication. Correct placement was confirmed by chest X-ray. A series of four immunoadsorptions was initiated and conducted on 4 consecutive days. No side effect of any kind was reported. Following the last immunoadsorption, the patient received 1 g cyclophosphamide which he tolerated well. Subsequently, the catheter was removed, allegedly not in supine position. Within minutes following catheter removal, the patient reported shortness of breath. Physical examination, ECG, chest X-ray and echocardiography were unremarkable at this time, and symptoms regressed. Ten hours later, the patient presented with diffuse sweating and severe dyspnoea, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 88% with 2 L O2/min. Physical examination showed signs of pulmonary oedema. The ECG at this time was reported as follows: sinus tachycardia, 130 bpm, no axis deviation, regular atrioventricular node transmission, regular R progression with R/S ratio >1 in V4 and no repolarisation disturbance. Within minutes, oxygen saturation fell to 66% and could not be stabilised despite increase of oxygen flow to 10 L/min. Following a short period of non-invasive ventilation, the patient was intubated and mechanically ventilated. During intubation, massive endotracheal secretion was visible, which was confirmed by bronchoscopy. Chest X-ray confirmed severe pulmonary oedema. The patient became progressively haemodynamically instable, and vasopressor therapy was initiated. The differential diagnosis at this time included toxic pulmonary oedema after cyclophosphamide12 13 and sepsis. Antibiotic therapy was initiated with piperacillin/sulbactam, clarithromycin and cephazolin.

Disease progression

During the following 6 hours, the patient deteriorated rapidly with respect to haemodynamics and oxygenation. He was transferred to the ICU of our hospital for ECMO. On arrival in our ICU, his SpO2 was 85% (partial pressure of oxygen 58 mm Hg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide 66 mm Hg) with pressure-controlled ventilation (fractional inspired oxygen 100%, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 23 cm H2O, peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) 43 cm H2O), blood pressure at 90/50 mm Hg, and heart rate 110/min with vasopressor support (norepinephrine 75 µg/kg/h). Laboratory analysis showed a remarkable leucocytosis of 92.1/nL (normal range 4.5–11.0) with 81% (normal range 40–70) granulocytes, 11% monocytes (normal range 2–6%), 7% lymphocytes (normal range 25–40%), no detectable eosinophilia, haemoglobin of 13.1 g/dL (normal range 13.5–17.5) and normal platelet count. Despite a rather low C reactive protein of 13 mg/L (normal range <8), his procalcitonin level was also markedly elevated to 100 µg/L (normal range <5). His creatinine was 328 µmol/L (normal range 59–104).

Physical examination showed a remarkable increase in the circumference of the neck (48 cm) due to oedema as well as signs of severe pulmonary oedema with massive endotracheal secretions. Addition of inhaled nitric oxide did not improve oxygenation. Within hours, the patient went into ventricular fibrillation. After defibrillation (3× 360 J) and 7 min of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), sinus rhythm and cardiac output were re-established, but the patient required extensive vasopressor support to maintain adequate blood pressure. To maintain oxygenation and circulation, venoarterial ECMO treatment was initiated after cannulation of the left femoral artery and right femoral vein. Kidney function deteriorated rapidly to anuric renal failure, and intermittent haemodialysis was initiated.

Investigations

A repeat echocardiography was unremarkable. Chest and abdominal CT scan confirmed pulmonary oedema and showed severe bilateral pleural effusions but no infectious focus or signs of pulmonary arterial embolism. The search for infectious agents was negative (including microbiological assessment of cultures from blood, tracheal secretion and urine; serological assessment for Pneumococcus Ag, Legionella Ag, Aspergillus Ag, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Varicella zoster virus (VZV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Herpes simplex virus (HSV), HIV, hepatitis, adenovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1/2/3, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus; PCR for adenovirus, coronavirus, human metapneumovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1/2/3, rhinovirus, enterovirus, respiratory syncytial virus A/B, influenza A/H1N1). Titres of antinuclear and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies were within the normal range. Complement levels were reduced (CH50: 59%; C3: 0.44 g/L; C4: 0.07 g/L). Bronchoalevolar lavage showed only sparse inflammatory cells (few granulocytes and lymphocytes).

Differential diagnosis

Thus, while the clinical presentation suggested a massive systemic inflammatory response, there was no evidence of any infectious agent. Autoimmune lung injury could potentially cause such fulminant clinical course, but one would expect pulmonary haemorrhage rather than fulminant pulmonary oedema. Furthermore, pulmonary manifestation of the necrotising glomerulonephritis (GN) is highly unlikely with IgA nephropathy, and anti-GBM antibodies were negative, ruling out Goodpasture's syndrome. An allergic reaction could potentially cause fulminant respiratory and circulatory failure. However, the typical presentation of respiratory failure with allergic reactions would be either obstructive (acute asthma) or restrictive with reduced diffusion capacity (allergic alveolitis). The severe pulmonary oedema in our patient would be an unusual presentation. In addition, no eosinophilia could be detected in the peripheral blood, and bronchoalveolar lavage showed only very few inflammatory cells, making an allergic reaction as underlying cause unlikely. A detailed clinical history (obtained from the patient's identical twin brother) confirmed the close relationship between removal of the dialysis catheter and onset of symptoms within seconds. The brother described a ‘slurping noise’ when the catheter was removed, followed by shortness of breath and dizziness. The symptoms subsided when pressure was applied to the catheter insertion site. Based on this history, we suspected pulmonary air embolism as the cause, resulting in local and later systemic activation of the inflammatory response cascade.

Treatment

Owing to the clinical severity and lack of alternative treatments, we initiated therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) to support removal of inflammatory mediators (despite the controversy regarding the benefit for this indication). TPE using the Terumo BCT centrifugal device was performed on 3 consecutive days. The calculated plasma volume before the first TPE was 2950 mL. The exchanged plasma volume at treatment #1–3 was 3063, 3270 and 3480 mL, respectively. Fresh frozen plasma was used as exchange fluid. Before each TPE an intravenous steroid dose of 100 mg as well as clemastine and ranitidine were given.

Outcome and follow-up

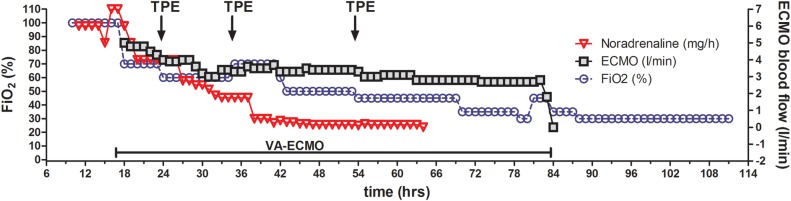

Haemodynamics and oxygenation stabilised under this treatment (figure 1), and within 4 days of initiation of ECMO treatment (and thus within 5 days of onset of symptoms) the patient could be weaned from ECMO and mechanical ventilation. Renal function improved, and intermittent haemodialysis could be stopped 7 days after transfer to our ICU. Serum creatinine stabilised around 5 mg/dL. After 8 days in the ICU the patient was transferred to a normal ward and could be discharged 2 weeks later, without any somatic sequelae.

Figure 1.

Time course of ventilator support and vasopressor therapy. This graph illustrates the severity of illness and rapid recovery that was made possible by bridging respiratory and circulatory failure with ECMO therapy. ECMO blood flow and FiO2 as well as Noradrenalin dose could be reduced within hours after starting therapy. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen; TPE, therapeutic plasma exchange; VA, venoarterial.

Discussion

The patient presented with a sudden onset and rapidly progressive pulmonary oedema with respiratory and circulatory failure that could not be stabilised with conventional ventilatory support and vasopressors. The initial differential diagnosis included toxic or infectious pulmonary oedema, toxic or infectious cardiomyopathy, and sepsis. transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) could be excluded as a differential diagnosis, as immunoadsorption is a procedure for which no blood products are used. Cyclophosphamide can rarely cause pulmonary toxicity14 but has not been reported to cause such fulminant respiratory failure. There was no evidence for infectious agents during work-up. Respiratory failure was rapid: intubation became necessary within an hour after onset of respiratory symptoms without any preceding features suggesting an infection. The remarkable extent of the vascular leakage with large amounts of pulmonary fluid is not a common picture usually seen in sepsis. The local neck swelling is puzzling. We have no formal imaging of the neck to determine what caused the swelling; however, massive air accumulation or haemorrhage would have been noted during the ultrasound examination performed during central line insertion, making it most likely that severe oedema as part of the generalised vascular leakage caused the neck swelling. The haemodynamic instability could not be explained by cardiac low-output failure: Echocardiography showed normal size and function of the left and right ventricle and no signs of right ventricular pressure overload or underfilling of the left ventricle.

The detailed history of events that was later given by the twin brother of the patient highlighted the close relationship of the onset of symptoms to the removal of the dialysis catheter. Clinical complications after placement of central vein catheters are not uncommon. A study by Farrell et al,15 analysing the placement of 460 internal jugular dialysis catheters, reported a total of 19.6% clinical complications, all of which occurred at the time of insertion. The causal relationship between the symptoms in the case reported here to catheter placement was especially difficult due to the late onset of the problem—days after insertion of the catheter and after discontinuation of the immunoadsorption treatment. Such a late-onset complication has not previously been reported.16 17 The ‘slurping noise’ on catheter removal, immediately followed by shortness of breath and dizziness, makes it likely that the catheter removal has a causal role in the further course of events.

The initial clinical presentation of our patient was characterised by unspecific symptoms (shortness of breath, dizziness, diffuse sweating), followed by a fulminant respiratory failure and systemic inflammatory response with progressive vascular leakage 10 hours later. This presentation is consistent with the pulmonary oedema and vascular leakage that can be induced by air embolism. Acute pulmonary oedema is a rare complication after venous air embolism.17 18 The severe systemic response with circulatory failure and massive vascular leakage that accompanied the pulmonary oedema in our patient was unusual and is not commonly seen after air embolism. In addition, the time lag of 10 hours between onset of severe symptoms and action of catheter removal is puzzling. Inflammatory states associated with systemic air embolism have been described in animal models,19 20 but the mechanism of this inflammatory response is unclear. It has been postulated that the disruption of microvascular flow by microscopic air bubbles cause agglomeration of polymorphonuclear leucocytes and platelet aggregation in the pulmonary capillaries, triggering the release of toxic oxygen metabolites and plasminogen-activator inhibitor.21 This mechanism can trigger the cascade of cytokines thought to be causative agents of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), among them interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor.22 The host response to these cytokines may include diffuse endovascular injury resulting in severe capillary leak and the clinical presentation of septic shock-like circulatory failure.

Further evidence for the role of microvascular bubbles in initiating an inflammatory response with endothelial injury comes from observations in decompression sickness (DCS). DCS is caused by intravascular bubbles that are formed as a result of reduction in ambient pressure.23 The central role of bubbles as an inciting factor for DCS is widely accepted, and several studies have focused on the role of bubbles and subsequent inflammatory response.24 25 In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated impaired endothelial cell activity and function after bubble contact.26–30 Moreover, decompression results in activation of erythrocytes, leucocytes and platelets as well as release of endothelial microparticles.31 These decompression-induced microparticles further enhance neutrophil activation and subsequent vascular injuries.32 33 Although evidence in the literature is sparse, it is feasible that the mechanism of the inflammatory response caused by air embolism in our patient resembles the events described in DCS. It is likely that the development of this inflammatory response (including recruitment of inflammatory cells and activation of cytokine production) with subsequent endothelial injury takes hours to develop. We postulate that this explains the time lag of several hours between catheter removal and deterioration of the clinical situation in our patient.

The rapid recovery is also typical of air-induced pulmonary injury. In a sheep model of air embolism, once the infusion of air is stopped, a rapid return to baseline values occurs within 24 hours without additional treatment. Thus, treatment should be supportive and include the use of oxygen and cardiorespiratory mechanical support if necessary. The presentation with SIRS-like symptoms prompted us to perform treatment with TPE in our patient. Although the role of TPE in modern sepsis therapy remains unclear, several case series and small randomised controlled trials suggest that TPE improves coagulation, haemodynamics and possibly survival in severe sepsis.34 Removal of cytokines using the Cytosorb device would have represented an alternative treatment, yet we deliberately chose to perform TPE using fresh frozen plasma, as we aimed to combine removal of cytokines with the replenishment of plasma components such as ADAMTS-13 whose decrease had been shown to be associated with poor prognosis in sepsis-induced organ failure.35 36

However, the key to treatment in this patient was the use of ECMO which made it possible to bridge the time until recovery. The clinical course of this patient underscores the effectiveness of this treatment and its potential to compensate respiratory and circulatory failure in acute and fulminant illnesses to such an extent that allows almost complete recovery within days.

Learning points.

This case highlights the severity of late-onset complications of catheter placements.

- Vigilance with respect to catheter-related complications should not only be directed to insertion of the catheter but also to catheter removal. Preventive measures should be applied carefully:

-

−During catheter removal: patient in supine position, Valsalva manoeuvre;

-

−Immediately after catheter removal: compression of the puncture site, and application of a sealing wound dressing);

-

−If complications arise during catheter insertion or removal, the patient should be monitored closely during the following hours.

-

−

Air embolism of pulmonary arteries usually manifests with dyspnoea, tachypnoea, coughing or syncope. However, pulmonary air embolism should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute pulmonary oedema. This is especially important in a setting where other diseases such as cardiac dysfunction or infection with septic complications may be automatically suspected, thus delaying appropriate treatment.

Our report shows the potential of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment for management of acute illness with bridge to recovery in acute respiratory and circulatory failure.

Footnotes

Contributors: GE, GB, MMH and JTK contributed to the concept of this case presentation. GE and JK drafted the manuscript; GB and MMH reviewed the manuscript critically and revised it. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Vanholder V, Hoenich N, Ringoir S. Morbidity and mortality of central venous catheter hemodialysis: a review of 10 years’ experience. Nephron 1987;47:274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kielstein JT, Abou-Rebyeh F, Hafer C et al. Right-sided chest pain at the onset of haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16:1493–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoeper MM, Wiesner O, Hadem J et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation instead of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:2056–7. 10.1007/s00134-013-3052-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terragni P, Faggiano C, Ranieri VM. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014;20:86–91. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kielstein JT, Heiden AM, Beutel G et al. Renal function and survival in 200 patients undergoing ECMO therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:86–90. 10.1093/ndt/gfs398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ius F, Kuehn C, Tudorache I et al. Lung transplantation on cardiopulmonary support: venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation outperformed cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1510–16. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuehner T, Kuehn C, Hadem J et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in awake patients as bridge to lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:763–8. 10.1164/rccm.201109-1599OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javidfar J, Brodie D, Iribarne A et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplantation and recovery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:716–21. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castleberry AW, Hartwig MG, Whitson BA. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation post lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2013;18:524–30. 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328365197e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng A, Hachamovitch R, Kittleson M et al. Clinical outcomes in fulminant myocarditis requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a weighted meta-analysis of 170 patients. J Card Fail 2014;20:400–6. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masson R, Colas V, Parienti JJ et al. A comparison of survival with and without extracorporeal life support treatment for severe poisoning due to drug intoxication. Resuscitation 2012;83:1413–17. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harigaya H, Matsubara K, Nigami H et al. Interstitial pneumonitis probably induced by cyclophosphamide in nephrosis. Acta Paediatr Jpn 1997;39:364–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehl A, Bergholz M, von Heyden HW et al. Toxic-allergic lung edema following cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide therapy. Case report. Onkologie 1983;6:84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik SW, Myers JL, DeRemee RA et al. Lung toxicity associated with cyclophosphamide use. Two distinct patterns. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1851 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell J, Walshe J, Gellens M et al. Complications associated with insertion of jugular venous catheters for hemodialysis: the value of postprocedural radiograph. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30:690–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quillen K, Magarace L, Flanagan J et al. Vascular erosion caused by a double-lumen central venous catheter during therapeutic plasma exchange. Transfusion 1995;35:510–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanherweghem JL, Cabolet P, Dhaene M et al. Complications related to subclavian catheters for hemodialysis. Report and review. Am J Nephrol 1986;6:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modi KS, Gross D, Davidman M. The patient developing chest pain at the onset of haemodialysis sessions—it is not always angina pectoris. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999;14:221–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanus-Santos JE, Gordo WM, Udelsmann A et al. Nonselective endothelin-receptor antagonism attenuates hemodynamic changes after massive pulmonary air embolism in dogs. Chest 2000;118:175–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryu KH, Hindman BJ, Reasoner DK et al. Heparin reduces neurological impairment after cerebral arterial air embolism in the rabbit. Stroke 1996;27:303–9; discussion 310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthay MA. Severe sepsis—a new treatment with both anticoagulant and antiinflammatory properties. N Engl J Med 2001;344:759–62. 10.1056/NEJM200103083441009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 2003;348:138–50. 10.1056/NEJMra021333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vann RD, Butler FK, Mitchell SJ et al. Decompression illness. Lancet 2011;377:153–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thom SR, Milovanova TN, Bogush M et al. Microparticle production, neutrophil activation and intravascular bubbles following open-water SCUBA diving. J Appl Physiol 2012;112:1268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thom SR, Milovanova TN, Bogush M et al. Bubbles, microparticles, and neutrophil activation: changes with exercise level and breathing gas during open-water SCUBA diving. J Appl Physiol 2013;114:1396–405. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00106.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobolewski P, Kandel J, Eckmann DM. Air bubble contact with endothelial cells causes a calcium-independent loss in mitochondrial membrane potential. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e47254 10.1371/journal.pone.0047254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobolewski P, Kandel J, Klinger AL et al. Air bubble contact with endothelial cells in vitro induces calcium influx and IP3-dependent release of calcium stores. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011;301:C679–86. 10.1152/ajpcell.00046.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madden LA, Chrismas BC, Mellor D et al. Endothelial function and stress response after simulated dives to 18 msw breathing air or oxygen. Aviat Space Environ Med 2010;81:41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazur A, Lambrechts K, Buzzacott P et al. Influence of decompression sickness on vasomotion of isolated rat vessels. Int J Sports Med 2014;35:551–8. 10.1055/s-0033-1358472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q, Mazur A, Guerrero F et al. Antioxidants, endothelial dysfunction, and DCS: in vitro and in vivo study. J Appl Physiol 2015;119:1355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thom SR, Yang M, Bhopale VM et al. Microparticles initiate decompression-induced neutrophil activation and subsequent vascular injuries. J Appl Physiol 2011;110:340–51. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00811.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brodsky SV, Zhang F, Nasjletti A et al. Endothelium-derived microparticles impair endothelial function in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286:H1910–15. 10.1152/ajpheart.01172.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mezentsev A, Merks RM, O'Riordan E et al. Endothelial microparticles affect angiogenesis in vitro: role of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;289:H1106–14. 10.1152/ajpheart.00265.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadem J, Hafer C, Schneider AS et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange as rescue therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock: retrospective observational single-centre study of 23 patients. BMC Anesthesiol 2014;14:24 10.1186/1471-2253-14-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin K, Borgel D, Lerolle N et al. Decreased ADAMTS-13 (A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats) is associated with a poor prognosis in sepsis-induced organ failure. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.David S, Thamm K, Schmidt BM et al. Effect of extracorporeal cytokine removal on vascular barrier function in a septic shock patient. J Intensive Care 2017;5:12 10.1186/s40560-017-0208-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]