Abstract

Objective

SLE is traditionally classified using the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) recently validated an alternative system. This study examined large cohorts of subjects with SLE and incomplete lupus erythematosus (ILE) to compare the impact of ACR and SLICC criteria.

Methods

Medical records of subjects in the Lupus Family Registry and Repository were reviewed for documentation of 1997 ACR classification criteria, SLICC classification criteria and medication usage. Autoantibodies were assessed by indirect immunofluorescence (ANA, antidouble-stranded DNA), precipitin (Sm) and ELISA (anticardiolipin). Other relevant autoantibodies were detected by precipitin and with a bead-based multiplex assay.

Results

Of 3575 subjects classified with SLE under at least one system, 3312 (92.6%) were classified as SLE by both systems (SLEboth), 85 only by ACR criteria (SLEACR-only) and 178 only by SLICC criteria (SLESLICC-only). Of 440 subjects meeting 3 ACR criteria, 33.9% (149/440) were SLESLICC-only, while 66.1% (n=291, designated ILE) did not meet the SLICC classification criteria. Under the SLICC system, the complement criterion and the individual autoantibody criteria enabled SLE classification of SLESLICC-only subjects, while SLEACR-only subjects failed to meet SLICC classification due to the combined acute/subacute cutaneous criterion. The SLICC criteria classified more African-American subjects by the leucopenia/lymphopenia criterion than did ACR criteria. Compared with SLEACR-only subjects, SLESLICC-only subjects exhibited similar numbers of affected organ systems, rates of major organ system involvement (∼30%: pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, neurological) and medication history.

Conclusions

The SLICC criteria classify more subjects with SLE than ACR criteria; however, individuals with incomplete lupus still exist under SLICC criteria. Subjects who gain SLE classification through SLICC criteria exhibit heterogeneous disease, including potential major organ involvement. These results provide supportive evidence that SLICC criteria may be more inclusive of SLE subjects for clinical studies.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Classification, Incomplete Lupus Erythematosus (ILE), Diagnosis

Introduction

The clinical and immunological heterogeneity of patients with SLE hinders timely diagnosis, effective management and treatment development. Clinical trials of SLE typically select subjects based on the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria,1 which require meeting ≥4 of 11 clinical and/or serological criteria. Although the ACR criteria remain a historical standard for identifying patients with SLE, individuals diagnosed with lupus by expert rheumatologists may not meet these criteria, while some who do meet the criteria have minimal disease. Therefore, ongoing efforts have sought more sensitive and specific criteria to identify patients with significant lupus.2

In 2012, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) validated new SLE classification criteria through a series of consensus exercises using symptomatology and laboratory results drawn from real rheumatologic cases.3 SLE classification using SLICC criteria requires either meeting ≥4 of 17 criteria, including at least one clinical and one immunological criterion, or demonstrating biopsy-proven lupus nephritis with positive ANA or antidouble-stranded (ds)DNA.3

Because SLICC criteria emphasise immunological and haematological lupus manifestations, it has been proposed that subjects who gain SLE classification through SLICC criteria may be less likely to exhibit clinically significant organ involvement compared with subjects classified through ACR criteria.4 To address this question, the current study compared subjects who were classified by SLICC criteria with other subjects with SLE and incomplete lupus erythematosus (ILE) in a large, well-characterised, racially and geographically diverse cohort.

Methods

Study subjects

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) Institutional Review Board. Study participants were previously enrolled to the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR)5 and provided written informed consent, detailed clinical questionnaire information, connective tissue disease screening questionnaire responses,6 demographic information, blood samples and medical records, which were reviewed for ACR1 and SLICC3 criteria and for medication history (see online supplementary methods, supplementary figure 1).

lupus-2016-000176supp.pdf (401.5KB, pdf)

Autoantibody detection

Autoantibodies were analysed by the College of American Pathologists-certified OMRF Clinical Immunology Laboratory. ANA and anti-dsDNA were analysed by indirect immunofluorescence, extractable nuclear antibodies by immunodiffusion and anticardiolipin by ELISA.7

Autoantibody specificities were compared using a multiplexed, bead-based assay (BioPlex 2200, Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) that simultaneously detects dsDNA, chromatin, ribosomal P, Ro/SSA (60 and 52 kDa), La/SSB, Sm, SmRNP complex, RNP, centromere B, Scl-70 and Jo-1 autoantibodies.8 Anti-dsDNA is reported in IU/mL with a manufacturer-specified positive cut-off of 10.0 IU/mL, and other specificities as an Antibody Index (AI) value (range 0–8) based on the fluorescence intensity of each of the other autoantibody specificities, with a manufacturer-recommended positive cut-off of AI=1.0.8

Statistical analyses

In R V.3.3.0 (R Foundation, https://www.r-project.org/), we compared means by unpaired t-test, medians by Mann-Whitney U test and proportions by either logistic regression using SLESLICC-only as the reference group or Fisher's exact test for comparisons with an observed value of 0. Two-sided p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Approximately one-third of subjects with 3 ACR criteria are classified with SLE by SLICC criteria

Medical record review of subjects in the LFRR identified 3397 subjects with SLE classified using ACR criteria. Of these, 3312 (97.5%) also reached SLICC classification (SLEboth), while 85 reached only ACR classification (SLEACR-only). An additional 178 reached only SLICC classification, but not ACR classification (SLESLICC-only). Approximately one-third of subjects with only three ACR criteria (149/440; 33.9%) met SLE classification by SLICC criteria. The other 291 subjects with three ACR criteria were not classified by SLICC criteria. These subjects, designated ILE, served as a comparison group expected to have more limited disease. Demographics were similar across the three SLE groups, while subjects with ILE were slightly older (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of subjects with SLE and ILE based on 2012 SLICC and 1997 ACR criteria

| SLESLICC-only* (n=178) | SLEACR-only† (n=85) | SLEboth‡ (n=3312) | ILE§ (n=291) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 160 (89.9) | 74 (87.0) p=0.494 |

2976 (89.9) p=0.989 |

255 (87.6) p=0.458 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Average (range) | 43.7 (10–81) | 45.4 (12–79) p=0.345 |

42.0 (8–82) p=0.118 |

47.5 (9–80) p=0.002 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| European American | 89 (50.0) | 52 (61.2) p=0.090 |

1466 (44.3) p=0.134 |

165 (56.7) p=0.158 |

| African-American | 44 (24.7) | 14 (16.5) p=0.133 |

1079 (32.6) p=0.030 |

69 (23.7) p=0.804 |

| Hispanic | 12 (6.7) | 5 (5.9) p=0.791 |

239 (7.2) p=0.811 |

12 (4.1) p=0.216 |

| Asian | 10 (5.6) | 2 (2.4) p=0.250 |

128 (3.9) p=0.245 |

10 (3.4) p=0.261 |

| American Indian | 2 (1.1) | 5 (5.9) p=0.044 |

99 (3.0) p=0.165 |

10 (3.4) p=0.144 |

| Mixed | 21 (11.8) | 7 (8.2) p=0.383 |

276 (8.3) p=0.109 |

22 (7.6) p=0.126 |

| Other¶ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) p=1.000 |

25 (0.8) p=0.985 |

3 (1.0) p=0.985 |

Bold p values are significant (p<0.05) for comparison with SLESLICC-only.

*SLESLICC-only were classified with SLE by SLICC criteria, but not ACR criteria.

†SLEACR-only were classified with SLE by ACR criteria, but not SLICC criteria.

‡SLEboth were classified with SLE by both SLICC and ACR criteria.

§Patients with ILE met three ACR criteria and were not classified with SLE by SLICC standards.

¶Other includes Pacific Islander and unknown.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ILE, incomplete lupus erythematosus; SLICC, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics.

Subjects who do not meet ACR classification criteria gain SLE classification through SLICC haematological, immunological and alopecia criteria

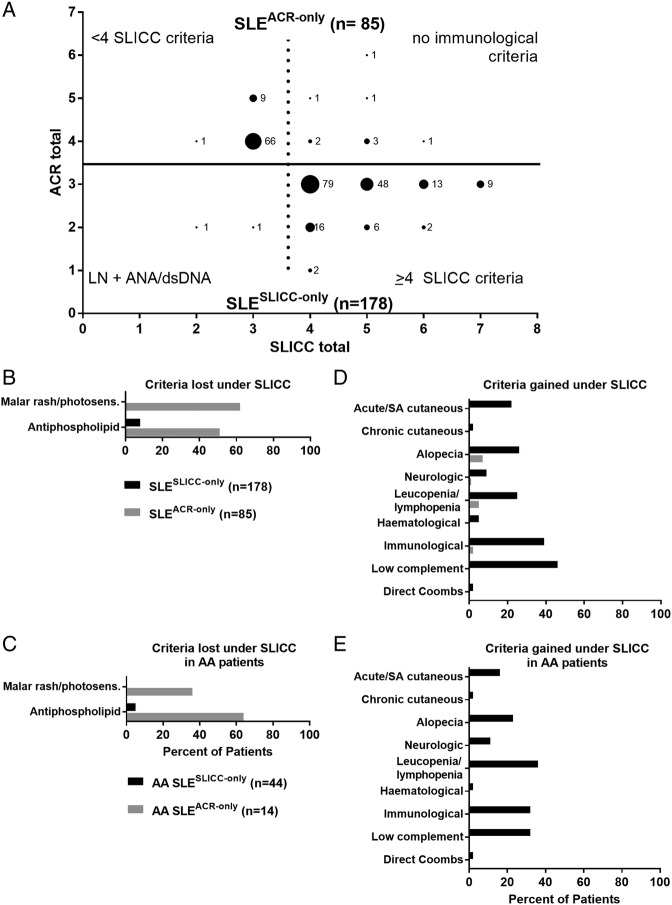

Two SLESLICC-only subjects (1.1%) were classified by SLICC criteria through biopsy-proven lupus nephritis with positive ANA or anti-dsDNA (figure 1A, bottom). The remaining 176 (98.9%) had one to four more SLICC criteria than ACR criteria. SLESLICC-only subjects gained criteria through low complement levels (81/178, 45.5%) and the separation of ACR immunological subcriteria into separate SLICC criteria (69/178, 38.8%), but African-American SLESLICC-only subjects most often gained criteria through the less stringent definition of leucopenia/lymphopenia (16/44, 36%) (figure 1D–E). Other than maculopapular rash, leading to a new criterion in 38 SLESLICC-only subjects (21.3%), and sensory neuropathy (14 SLESLICC-only subjects; 7.9%), new SLICC subcriteria made little contribution to additional individuals reaching SLE classification (see online supplementary figure 3).

Figure 1.

Subjects gain SLE classification through Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria of low complement, immunological manifestations and leucopenia/lymphopenia. (A) Medical record review identified subjects classified with SLE by American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria only (n=85; top, grey) or by SLICC criteria only (n=178; bottom, black). Labelled dots indicate the number of subjects who satisfied a given number of ACR criteria (y-axis) and SLICC criteria (x-axis). Criteria lost (B, C) or gained (D, E) under the SLICC system compared with the ACR system were evaluated in all SLESLICC-only (black) and SLEACR-only (grey) subjects (B, D) or in subjects self-reporting African-American race (C, E). See online supplementary figure 2 for criteria gained and lost in European American and other subjects. AA, African American; dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA; LN, lupus nephritis; SA, subacute.

Of the 85 SLEACR-only subjects, 76 (89.4%) met <4 SLICC criteria (figure 1A, top). Nine (10.6%) met ≥4 SLICC clinical criteria, but were excluded by SLICC criteria due to an absence of immunological criteria. Loss of SLE classification by SLICC criteria was primarily due to the combination of malar rash and photosensitivity into a single SLICC criterion (53/85; 62.4% of SLEACR-only; figure 1B, see online supplementary figure 1). However, among African-American SLEACR-only subjects, the majority lost a criterion due to the stricter threshold for anticardiolipin positivity (figure 1C).

Subjects classified with SLE only by SLICC criteria share clinical and immunological features with other subjects with SLE, including major organ involvement

Acute/subacute cutaneous rashes, arthritis and leucopenia/lymphopenia were the most common SLICC clinical criteria in all groups (table 2). SLESLICC-only subjects exhibited relatively low prevalence of acute/subacute cutaneous rashes and arthritis, but higher prevalence of alopecia, leucopenia/lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia. SLESLICC-only and SLEboth subjects exhibited similar prevalence of multiple SLICC immunological criteria and had more SLICC immunological criteria than SLEACR-only or ILE (table 2). SLESLICC-only sera displayed significantly more autoantibody specificities and higher prevalence of lupus-associated specificities than SLEACR-only or ILE. SLEboth displayed the highest number and prevalence of lupus-associated specificities. Autoantibodies not specifically associated with lupus (anticentromere B, anti Scl-70 and anti Jo-1), were observed at low frequencies in all groups. The rate of major clinical involvement (serositis, renal or neurological) did not differ between SLESLICC-only and SLEACR-only (48/178, 27.0% vs 19/85, 22.4%; p=0.422), but was significantly lower in SLESLICC-only compared with SLEboth (2098/3312, 63.3%; p<0.0001) and higher compared with ILE (38/291, 11.3%; p<0.0001; see online supplementary table S1).

Table 2.

SLICC criteria, autoantibody specificities and medication history in patients with SLE and ILE based on SLICC and 1997 ACR criteria

| SLESLICC-only† (n=178) | SLEACR-only‡ (n=85) | SLEboth§ (n=3312) | ILE¶ (n=291) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLICC clinical criteria | ||||

| Number positive, mean | 2.06 | 2.27 p=0.244 |

4.15 p<0.0001 |

1.45 p<0.0001 |

| Acute/subacute cutaneous rashes, n (%) | 76 (42.7) | 71 (83.5) p<0.0001 |

2514 (75.9) p<0.0001 |

124 (42.6) p=0.986 |

| Chronic cutaneous rashes, n (%) | 10 (5.6) | 6 (7.1) p=0.648 |

562 (17.0) p<0.001 |

26 (8.9) p=0.194 |

| Oral/nasal ulcers, n (%) | 11 (6.2) | 13 (15.3) p=0.020 |

934 (28.2) p<0.0001 |

31 (10.6) p=0.104 |

| Alopecia, n (%) | 46 (25.8) | 6 (7.1) p=0.001 |

1248 (37.7) p=0.002 |

2 (0.7) p<0.0001 |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 67 (37.6) | 46 (54.1) p=0.012 |

2344 (70.8) p<0.0001 |

131 (45.0) p=0.117 |

| Serositis, n (%) | 10 (5.6) | 9 (10.6) p=0.152 |

1198 (36.2) p<0.0001 |

17 (5.8) p=0.920 |

| Renal, n (%) | 23 (12.9) | 9 (10.6) p=0.589 |

1262 (38.1) p<0.0001 |

13 (4.5) p=0.001 |

| Neurological, n (%) | 22 (12.4) | 5 (5.9) p=0.113 |

585 (17.7) p=0.071 |

4 (1.4) p<0.001 |

| Anaemia, n (%)* | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) p=0.553 |

253 (7.6) p=0.007 |

1 (0.3) p=0.166 |

| Leucopenia/lymphopenia, n (%) | 83 (46.6) | 26 (30.6) p=0.014 |

2339 (70.6) p<0.0001 |

67 (23.0) p<0.0001 |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | 16 (9.0) | 2 (2.4) p=0.064 |

498 (15.0) p=0.029 |

5 (1.7) p=0.001 |

| SLICC immunological criteria | ||||

| Number positive, mean | 2.54 | 0.90 p<0.0001 |

2.86 p<0.001 |

1.25 p<0.0001 |

| ANA, n (%) | 176 (98.9) | 74 (87.1) p=0.001 |

3299 (99.6) p=0.165 |

280 (96.2) p=0.109 |

| Anti-dsDNA, n (%) | 93 (52.2) | 2 (2.4) p<0.0001 |

2128 (64.3) p=0.001 |

34 (11.7) p<0.0001 |

| Anti-Sm, n (%) | 32 (18.0) | 1 (1.2) p=0.004 |

807 (24.4) p=0.053 |

8 (2.8) p<0.0001 |

| Antiphospholipid, n (%)* | 67 (37.6) | 0 (0.0) p<0.0001 |

1016 (30.7) p=0.051 |

39 (13.4) p<0.0001 |

| Complement, n (%)* | 81 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) p<0.0001 |

1884 (56.9) p=0.003 |

3 (1.0) p<0.0001 |

| Coombs, n (%)* | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) p=0.553 |

323 (9.8) p=0.002 |

0 (0.0) p=0.054 |

| Autoantibody specificities** | ||||

| Number positive, median | 1 | 0 p=0.004 |

2 p<0.0001 |

1 p<0.0001 |

| dsDNA, n (%) | 37 (22.7) | 1 (1.6) p=0.005 |

803 (30.2) p=0.043 |

13 (4.5) p<0.0001 |

| Chromatin, n (%) | 62 (38.0) | 12 (19.0) p=0008 |

1433 (53.9) p=0.0001 |

47 (16.4) p<0.0001 |

| Ribosomal P, n (%) | 9 (5.5) | 2 (3.2) p=0.468 |

355 (13.4) p=0.005 |

3 (1.0) p=0.011 |

| Ro/SSA, n (%) | 48 (29.4) | 16 (25.4) p=0.545 |

1049 (39.5) p=0.011 |

64 (22.4) p=0.097 |

| La/SSB, n (%) | 17 (10.4) | 4 (6.3) p=0.348 |

388 (14.6) p=0.142 |

24 (8.4) p=0.472 |

| Sm, n (%) | 24 (14.7) | 4 (6.3) p=0.096 |

726 (27.3) p=0.0005 |

17 (5.9) p=0.003 |

| SmRNP, n (%) | 45 (27.6) | 11 (17.5) p=0.116 |

1056 (39.7) p=0.002 |

35 (12.2) p<0.0001 |

| RNP, n (%) | 44 (27.0) | 12 (19.0) p=0.217 |

954 (35.9) p=0.022 |

45 (15.7) p=0.004 |

| Centromere B, n (%) | 6 (3.7) | 2 (3.2) p=0.853 |

100 (3.8) p=0.957 |

19 (6.6) p=0.194 |

| Scl-70, n (%) | 6 (3.7) | 2 (3.2) p=0.854 |

72 (2.7) p=0.465 |

6 (2.1) p=0.323 |

| Jo-1, n (%)* | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) p=1.000 |

8 (0.3) p=1.000 |

2 (0.7) p=0.537 |

| Medications used | ||||

| Number, median | 2 | 2 p=0.212 |

3 p<0.0001 |

2 p<0.0001 |

| None, n (%) | 12 (6.7) | 4 (4.7) p=0.052 |

34 (1.0) p<0.0001 |

45 (15.5) p=0.006 |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 133 (74.7) | 66 (77.6) p=0.605 |

2755 (83.2) p=0.004 |

173 (59.4) p<0.0001 |

| Steroids, n (%) | 147 (82.6) | 67 (78.8) p=0.464 |

3105 (93.8) p<0.0001 |

187 (64.3) p<0.0001 |

| Immunosuppressants, n (%) | 60 (33.7) | 25 (29.4) p=0.486 |

1683 (50.8) p<0.0001 |

80 (27.5) p=0.154 |

| Major immunosuppressants, n (%) | 41 (23.0) | 11 (12.9) p=0.058 |

1309 (39.5) p<0.0001 |

30 (10.3) p<0.001 |

Bold p values are significant (p<0.05) for comparison with SLESLICC-only by logistic regression or by Fisher's exact test where indicated (*) due to a 0 value. Note that power may be inadequate to detect differences when events are rare, particularly when the total n is also low, as for SLEACR-only.

†SLESLICC-only were classified with SLE by SLICC criteria, but not ACR criteria.

‡SLEACR-only were classified with SLE by ACR criteria, but not SLICC criteria.

§SLEboth were classified with SLE by both SLICC and ACR criteria.

¶Patients with ILE met three ACR criteria and were not classified with SLE by SLICC criteria.

**Determined by in-house, multiplex, bead-based assay.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ILE, incomplete lupus erythematosus; SLICC, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics.

Subjects classified with SLE by only SLICC or only ACR criteria demonstrate similar medication histories

Nearly all subjects had used at least one lupus-related medication type, including hydroxychloroquine, steroids, immunosuppressants (methotrexate, azathioprine and sulfasalazine) and/or major immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide) (table 2). Neither the number of medication types used nor the use of each medication type differed significantly between SLESLICC-only and SLEACR-only. Major immunosuppressant use was slightly more common among SLESLICC-only subjects compared with SLEACR-only subjects, but this difference was non-significant. Medication use was greatest in SLEboth and lowest in ILE.

Discussion

In a heterogeneous disease, optimised classification criteria would maximise inclusion of patients with clinically significant disease and exclude those without it. Although classification criteria are in many ways more restrictive than diagnostic criteria, classification criteria may directly impact patient access to new biologics; belimumab was approved only for patients meeting SLE classification criteria, since the trials excluded all others. While limited by retrospective design using community-based medical records from clinical care, lack of follow-up data and relatively small number of SLEACR-only subjects, this study provides new insights to patients identified by ACR and SLICC classification criteria.

The most ill patients with obvious, multiple-organ SLE are classified by both ACR and SLICC criteria. Therefore, we compared these criteria in a large collection of patients with partial lupus syndromes. Twice as many subjects met only SLICC criteria (SLESLICC-only) as met only ACR criteria (SLEACR-only), consistent with previous reports suggesting increased sensitivity of SLICC compared with ACR criteria.3 9–13 However, SLICC criteria did exclude many subjects with clinically suggestive features of lupus. Despite a relatively low prevalence of acute/subacute cutaneous rashes and arthritis, SLESLICC-only subjects displayed a phenotypic range similar to other patients with SLE and distinct from ILE, including haematological, immunological and major organ system (serositis, renal or neurological) involvement. They were also younger than subjects with ILE, supporting the probability of a defined connective tissue disease.14

Consistent with previous studies,11 12 SLEACR-only subjects primarily lost SLE classification under SLICC criteria due to the combination of malar rash and photosensitivity; SLESLICC-only subjects primarily gained a criterion through low complement. African-Americans comprised >30% of our registry and primarily gained classification through the SLICC leucopenia/lymphopenia criterion or lost classification due to the stricter SLICC antiphospholipid criterion. In the absence of racially informed reference values, the leucopenia/lymphopenia criterion may lead to misclassification of patients with benign leucopenia of ethnicity; this highlights the need to consider racial diversity when developing and applying SLE classification criteria.15

Disease severity did not differ between SLESLICC-only and SLEACR-only subjects, based on major organ system involvement and medication history. Along with a trend for increased major immunosuppressant use, SLESLICC-only subjects presented several features associated with increased risk for morbidity and mortality, including a marginally higher proportion of minority subjects and increased prevalence of thrombocytopenia, anti-dsDNA and anticardiolipin responses compared with SLEACR-only.16 17 Therefore, although they lack ACR classification, patients who gain classification under SLICC criteria appear to have significant disease, and prospective study is warranted. Additionally, immunological and haematological similarities between SLESLICC-only and SLEboth subjects suggest that these patients might benefit from the same mechanistically targeted treatments and could be included in the same trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the personnel and participants of the Lupus Family Registry and Repository. The authors thank Cathy Velte, Camille Anderson, Sandy Long and Tim Gross for technical assistance and Miles Smith for scientific editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: TA, RLB, JTM, JBH, NJO, DRK and JAJ designed the study. TA, VCR, JMG, JMR, KLS, AR, JTM, JBH, NJO, DRK and JAJ participated in data acquisition. TA, RLB, HC, JMG, KB, JMR, ML, JTM, JBH, NJO, DRK and JAJ participated in data analysis and/or interpretation. All authors assisted with the development of the manuscript and approved the final version to be published. JAJ had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the US NIH through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (U19AI082714, U01AI101934 and R37AI24717), Institutional Development Awards (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P30GM103510 and U54GM104938), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (P30AR053483, P30AR070549), the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01HG008666), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R24HL105333) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK107502). This work was also supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (I01BX001834). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. NJO reports grants from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Resolve Therapeutics, Horizon Pharmaceuticals, Roche/Genentech and Aurinia Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data for this study are being published.

References

- 1.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725 doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199709)40:9<1725::AID-ART29>3.0.CO;2-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petri M. Review of classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2005;31:245–54, vi doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–86. doi:10.1002/art.34473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amezcua-Guerra LM, Higuera-Ortiz V, Arteaga-Garcia U et al. Performance of the 2012 SLICC and the 1997 ACR classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus in a real-life scenario. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen A, Sevier S, Kelly JA et al. The lupus family registry and repository. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:47–59. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walitt BT, Constantinescu F, Katz JD et al. Validation of self-report of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: The Women's Health Initiative. J Rheumatol 2008;35:811–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinlen LD, McClain MT, Merrill J et al. Clinical criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus precede diagnosis, and associated autoantibodies are present before clinical symptoms. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2344–51. doi:10.1002/art.22665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruner BF, Guthridge JM, Lu R et al. Comparison of autoantibody specificities between traditional and bead-based assays in a large, diverse collection of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and family members. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:3677–86. doi:10.1002/art.34651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ighe A, Dahlstrom O, Skogh T et al. Application of the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria to patients in a regional Swedish systemic lupus erythematosus register. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:3 doi:10.1186/s13075-015-0521-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sag E, Tartaglione A, Batu ED et al. Performance of the new SLICC classification criteria in childhood systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicentre study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:440–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ines L, Silva C, Galindo M et al. Classification of systemic lupus erythematosus: systemic lupus international collaborating clinics versus American College of Rheumatology criteria. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:1180–5. doi:10.1002/acr.22539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pons-Estel GJ, Wojdyla D, McGwin G Jr et al. The American College of Rheumatology and the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus in two multiethnic cohorts: a commentary. Lupus 2014;23:3–9. doi:10.1177/0961203313512883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ungprasert P, Sagar V, Crowson CS et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus in a population-based cohort using revised 1997 American College of Rheumatology and the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria. Lupus 2016;26:240–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calvo-Alen J, Alarcon GS, Burgard SL et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: predictors of its occurrence among a cohort of patients with early undifferentiated connective tissue disease: multivariate analyses and identification of risk factors. J Rheumatol 1996;23:469–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams EM, Bruner L, Adkins A et al. I too, am America: a review of research on systemic lupus erythematosus in African-Americans. Lupus Sci Med 2016;3:e000144 doi:10.1136/lupus-2015-000144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziakas PD, Dafni UG, Giannouli S et al. Thrombocytopenia in lupus as a marker of adverse outcome—seeking Ariadne's thread. Rheumatol 2006;45:1261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petri M, Purvey S, Fang H et al. Predictors of organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:4021–8. doi:10.1002/art.34672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

lupus-2016-000176supp.pdf (401.5KB, pdf)