Abstract

Objectives

Inflammation-based prognostic markers (neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), prognostic nutritional index (PNI), red cell distribution width (RDW) and lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR)) are associated with overall survival in some diseases. This study assessed their prognostic value in mortality and severity in acute pancreatitis (AP).

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Patients with AP were recruited from the emergency department at our hospital.

Participants

A total of 359 patients with AP (31 non-survivors) were enrolled.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Mortality and severity of AP were the primary and secondary outcome measures, respectively. Biochemistry and haematology results of the first test after admission were collected. Independent relationships between severe AP (SAP) and markers were assessed using multivariate logistic regression models. Mortality prediction ability was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Overall survival was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences compared using the log-rank test. Independent relationships between mortality and each predictor were estimated using the Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

Compared with survivors of AP, non-survivors had higher RDW (p<0.001), higher NLR (p<0.001), lower LMR (p<0.001) and lower PNI (p<0.001) at baseline. C reactive protein (CRP; OR=8.251, p<0.001), RDW (OR=2.533, p=0.003) and PNI (OR=7.753, p<0.001) were independently associated with the occurrence of SAP. For predicting mortality, NLR had the largest area under the ROC curve (0.804, p<0.001), with a 16.64 cut-off value, 82.4% sensitivity and 75.6% specificity. RDW was a reliable marker for excluding death owing to its lowest negative likelihood ratio (0.11). NLR (HR=4.726, p=0.004), CRP (HR=3.503, p=0.003), RDW (HR=3.139, p=0.013) and PNI (HR=2.641, p=0.011) were independently associated with mortality of AP.

Conclusions

NLR was the most powerful marker of overall survival in this patient series.

Keywords: acute pancreatitis, mortality, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, prognostic nutritional index

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Compared with survivors of acute pancreatitis (AP), non-survivors had higher red cell distribution width (RDW) and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and lower lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR) and prognostic nutritional index (PNI) at baseline.

NLR exhibited a higher area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for the prediction of mortality compared with other markers.

RDW was suitable as a reliable marker to exclude death.

NLR, PNI, C reactive protein and RDW were independently associated with overall survival of AP.

This was a retrospective cohort analysis.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is rapid-onset inflammation of the pancreas that varies in severity from a self-limiting mild illness to rapidly progressive multiple organ failure. Statistics suggest that 10–20% of patients with AP develop severe AP (SAP),1 which usually has an unfavourable disease progression and is associated with a poor prognosis.2 3 Prediction of disease severity can guide the management of patients with AP and improve the outcome. Organ failure and infected pancreatic necrosis are common causes of mortality in such patients,4 and a new international multidisciplinary classification of SAP incorporates both events as determinants of severity.5 The predictive values of various markers, such as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis scores, C reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been previously assessed.6–8 A systematic review concluded that it was justifiable to use blood urea nitrogen after 48 hours of hospital admission for predicting persistent organ failure.9 In clinical studies, most studies have focused on disease severity, and only a few have directly investigated the relationship between predictors and mortality of AP. Furthermore, no reliable predictor of persistent organ failure within 48 hours of admission has been identified.9

There is increasing evidence that the presence of a systemic inflammatory response is associated with poor survival in patients with various aetiologies, including malignancy.10–17 Many direct or combined markers of systemic inflammation are based on routine, inexpensive and readily available laboratory tests. Red cell distribution width (RDW),10 neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), prognostic nutritional index (PNI)11 and lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR)12 have been used to predict the prognosis of disease. RDW was found to be an independent marker of short-term and long-term prognosis in intensive care units.10 NLR at admission served as an independent predictor of 3-month mortality rates in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure.13 Increased pretreatment LMR was associated with a significantly more favourable prognosis in patients with solid tumours.12 Despite this evidence, very few studies have focused on the direct relationship between inflammation-based prognostic markers and mortality of AP. A cross-sectional study found a significant association between RDW and mortality in patients with AP.18 Another study investigated the prognostic value of NLR in AP and determined an optimal ratio for prediction of severity.19

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to simultaneously compare the prognostic value of these inflammation-based prognostic markers (NLR, PNI, CRP, RDW and LMR) of mortality in patients with AP.

Materials and methods

Participants

This retrospective cohort analysis consecutively enrolled a series of patients with AP who were admitted to the emergency department at our hospital between 1 July 2013 and 18 August 2015. A diagnosis of AP required two of three features: (1) prolonged abdominal pain characteristic of AP, (2) threefold elevation of serum amylase and/or lipase levels above the normal range, and (3) characteristic findings of AP on abdominal ultrasonography and/or CT scan.1 Mild AP (MAP) was defined as an absence of organ failure and an absence of local or systemic complications.1 Moderately SAP (MSAP) was defined as no evidence of persistent organ failure, but the presence of local or systemic complications and/or organ failure that resolved within 48 hours. SAP was defined as persistent organ failure (>48 hours).1 Patients with recurrent pancreatitis were enrolled only at first admission. Patients with traumatic pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, diabetes mellitus, tumour or liver failure were excluded.

The prognostic information we focused on included overall survival and the severity of the disease. All enrolled patients were followed for 100 days or until death. All clinical data were retrieved from medical records. For patients with AP, 100 days of prognostic information (survival or non-survival) was obtained by checking medical records or by contacting the patients' family members.

Ethics statement

Each participant provided written informed consent after being provided with an explanation of the study by phone, letter or email. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles contained within the Declaration of Helsinki.

Demographic information and laboratory analysis

Demographic information, including age, sex, aetiology and complication, was collected from medical records. Pretreatment laboratory data, including complete blood counts, serum CRP, albumin and amylase, were obtained during the emergency visit. An XE-2100 haematology autoanalyser (Sysmex Corp, Kobe, Japan), a Hitachi 7600 chemistry analyser (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) and Roche reagents (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) were used in the laboratory.

We assessed the prognostic value of general inflammation-based prognostic markers (NLR, CRP, RDW, PNI and LMR) for predicting the mortality of AP. Additionally, their ability to predict the severity of AP (SAP or not SAP) was assessed. NLR and LMR were ratios of two types of blood cell. PNI=albumin (g/L)+5×total lymphocyte count (109/L).

Statistical analysis

Variables are expressed as mean±SD or median (range) and categorical data as percentages, as appropriate. Differences between the two groups were assessed using an independent sample t-test, Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 test, as appropriate. Multiple comparisons were performed by one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis H tests, as appropriate. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to assess whether the inflammation markers were independent factors for predicting SAP in patients with AP by unadjusted and adjusted models successively. Patients with AP were randomly divided into estimation and validation cohorts by random number generators. The accuracy of each marker to predict mortality was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (+LR) and negative likelihood ratio (−LR) were calculated. +LR represents the ratio of the true-positive rate to the false-positive rate. −LR represents the ratio of the false-negative rate to the true-negative rate. These two parameters, which are not influenced by prevalence rate, are stable and objective for assessing diagnostic value. Combination models were developed using binary logistic regression analyses. Overall survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival rates were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the significance and independence of the relationship of each marker and mortality. The variables with a p value <0.1 in univariate analysis were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 359 patients with AP (197 MAP, 76 MSAP and 86 SAP) were enrolled in the study. The predefined probability of type I error was 0.05 (α=0.05), and the sample size was large enough to guarantee 0.90 of test power (β=0.1). Forty-five patients were excluded from the analysis, including those with traumatic pancreatitis (n=1), autoimmune pancreatitis (n=5), diabetes mellitus (n=7), tumour (n=7), liver failure (n=2) or incomplete medical records or who were lost to follow-up (n=23). Tables 1 and 2 show the baseline characteristics of the patients. There were no significant differences in age (p=0.352), aetiology (p=0.875) or sex (p=0.919) among the three groups (MAP, MSAP and SAP). As the illness worsened, CRP, RDW and NLR gradually increased, but PNI decreased (all p<0.05; table 1). LMR decreased significantly (p<0.001) in patients with MSAP compared with patients with MAP, but there was no significant difference between patients with MSAP and patients with SAP (p=0.883).

Table 1.

Demographics and laboratory findings in patients with acute pancreatitis

| Variables | (1) MAP (n=197) | (2) MSAP (n=76) | (3) SAP (n=86) | p Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All groups | 1 vs 2 | 2 vs 3 | ||||

| Age (years) | 51.43±16.00 | 48.47±13.28 | 50.69±14.61 | 0.352 | 0.446 | 1.000 |

| Male (%) | 108 (54.8%) | 41 (53.9%) | 49 (57.0%) | 0.919 | 0.896 | 0.699 |

| Aetiology (1/2/3/4)% | 52%/12%/11%/25% | 51%/16%/13%/20% | 47%/15%/14%/24% | 0.875 | 0.664 | 0.892 |

| WCC (×109/L) | 11.5 (3.1–32.0) | 14.1 (4.5–36.8) | 16.05 (5.9–38.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.278 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/L) | 1.1 (0.2–9.4) | 1.0 (0.2–2.6) | 0.80 (0.2–2.9) | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.089 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 202 (21–502) | 193 (58–548) | 163 (27–540) | 0.004 | 0.376 | 0.046 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.29±5.07 | 34.38±6.39 | 29.99±5.35 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 53.9 (0.7–386) | 133.6 (3.2–436.5) | 196.1 (27.1–426.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 398 (13–5191) | 222 (27–3845) | 581 (16–2377) | 0.141 | 0.083 | 0.056 |

| RDW (%) | 12.8 (11.4–19.2) | 13.0 (11.3–16.3) | 13.7 (11.7–23.6) | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.014 |

| NLR | 8.46 (1.33–55) | 14.60 (1.73–60) | 19.65 (3.57–53.67) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.020 |

| LMR | 1.88 (0.28–13.33) | 1.03 (0.29–5.33) | 1.14 (0.22–6.32) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.883 |

| PNI | 44.53±6.63 | 39.36±6.71 | 34.55±6.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (36.0%) | <0.001 | – | <0.001 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median (range).

Aetiology (1/2/3/4)%, 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent gallstone, alcohol, hypertriglyceridaemia and other aetiologies, respectively.

1 vs 2, MAP group versus MSAP group; 2 vs 3, MSAP group versus SAP group.

CRP, C reactive protein; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; MAP, mild acute pancreatitis; MSAP, moderately severe acute pancreatitis; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width; SAP, severe acute pancreatitis; WCC, white cell count.

Table 2.

Demographics and laboratory findings in survivors and non-survivors of acute pancreatitis

| Variables | Survivors (n=328) | Non-survivors (n=31) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.84±14.88 | 58.90±15.60 | 0.001 |

| Male (%) | 179 (54.6%) | 19 (61.3%) | 0.472 |

| Aetiology (1/2/3/4)% | 50%/13%/12%/25% | 58%/19%/10%/13% | 0.346 |

| WCC (×109/L) | 12.85 (3.1–38.4) | 18.5 (6.5–29.3) | 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes (×109/L) | 1.08 (0.17–9.40) | 0.60 (0.30–1.60) | <0.001 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 197 (21–548) | 159 (27–376) | 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35.95±6.30 | 30.44±5.54 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 98.6 (0.7–436.5) | 239.2 (27.1–398.2) | <0.001 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 343.5 (13–5191) | 909 (16–2377) | 0.010 |

| RDW (%) | 13 (11.3–19.2) | 13.8 (12.6–23.6) | <0.001 |

| NLR | 10.47 (1.33–60.0) | 25.0 (8.67–53.67) | <0.001 |

| PNI | 41.71±7.50 | 34.00±6.35 | <0.001 |

| LMR | 1.51 (0.22–13.33) | 1.13 (0.24–2.26) | <0.001 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median (range).

Aetiology (1/2/3/4)%, 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent gallstone, alcohol, hypertriglyceridaemia and other aetiologies, respectively.

CRP, C reactive protein; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width; WCC, white cell count.

Compared with survivors of AP, non-survivors were older (p=0.001) and had higher CRP (p<0.001), amylase (p=0.010), RDW (p<0.001) and NLR (p<0.001). Conversely, lymphocyte count (p<0.001), platelets (p=0.001), albumin (p<0.001), LMR (p<0.001) and PNI (p<0.001) were lower in non-survivors than in survivors (table 2).

The relationship between markers and severity of AP

The multivariate logistic regression models revealed that high CRP (>110 vs ≤110 mg/L, adjusted OR=8.251, 95% CI 3.897 to 17.468, p<0.001), RDW (>13.0% vs ≤13.0%, adjusted OR=2.533, 95% CI 1.365 to 4.702, p=0.003) and low PNI (<41.1 vs ≥41.1, adjusted OR=7.753, 95% CI 3.400 to 17.680, p<0.001) were independent factors for predicting SAP in patients with AP (table 3).

Table 3.

ORs of prognostic factors for predicting SAP in patients with AP

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| NLR (>11.36 vs ≤11.36) | 3.707 (2.173 to 6.326) | <0.001 | 3.578 (2.082 to 6.149) | <0.001 | 1.463 (0.711 to 3.010) | 0.301 |

| CRP(>110 vs ≤110 mg/L) | 9.867 (5.116 to 19.030) | <0.001 | 12.609 (6.304 to 25.218) | <0.001 | 8.251 (3.897 to 17.468) | <0.001 |

| RDW (>13.0% vs ≤13.0%) | 3.368 (2.003 to 5.663) | <0.001 | 3.529 (2.076 to 5.998) | <0.001 | 2.533 (1.365 to 4.702) | 0.003 |

| PNI (<41.1 vs ≥41.1) | 9.951 (5.055 to 19.589) | <0.001 | 11.356 (5.665 to 22.766) | <0.001 | 7.753 (3.400 to 17.680) | <0.001 |

| LMR (<1.43 vs ≥1.43) | 2.564 (1.539 to 4.271) | <0.001 | 2.552 (1.524 to 4.274) | <0.001 | 0.722 (0.355 to 1.471) | 0.370 |

Model 1: unadjusted model.

Model 2: adjusted for age, gender and amylase.

Model 3: NLR was adjusted for age, gender, amylase, CRP, RDW, PNI and LMR; CRP was adjusted for age, gender, amylase, NLR, RDW, PNI and LMR; RDW was adjusted for age, gender, amylase, CRP, NLR, PNI and LMR; PNI was adjusted for age, gender, amylase, NLR, CRP, RDW and LMR; LMR was adjusted for age, gender, amylase, NLR, CRP, RDW and PNI.

AP, acute pancreatitis; CRP, C reactive protein; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width; SAP, severe acute pancreatitis.

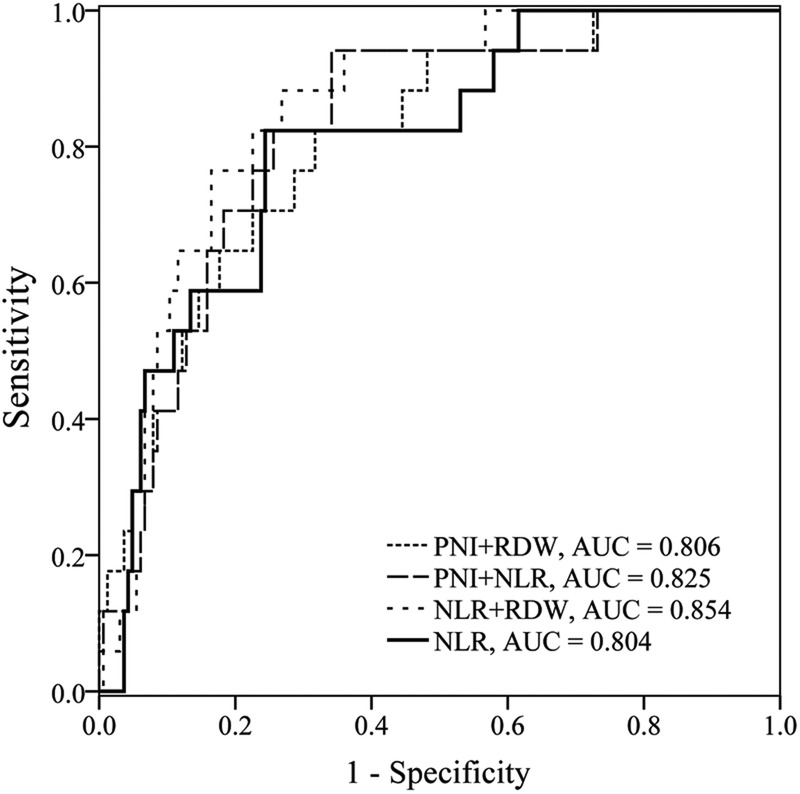

The markers' power for predicting 100 days mortality

The enrolled 359 patients with AP were randomly grouped into two cohorts: the estimation cohort (n=181) and the validation cohort (n=178). No significant difference was observed between the estimation and the validation cohorts in all characteristics (see online supplementary table S1). ROC curves of the estimation cohort were constructed to evaluate the ability of each marker to predict 100 days mortality in AP. Table 4 shows the area under the ROC curves (AUC) and optimal cut-off values. The ability of NLR to predict mortality (AUC=0.804, p<0.001) was good; those of PNI (AUC=0.769, p<0.001), CRP (AUC=0.774, p<0.001), RDW (AUC=0.769, p<0.001) and LMR (AUC=0.744, p<0.001) were fair. The NLR had the largest AUC, and RDW and PNI had the highest sensitivity and specificity, respectively. Therefore, these three markers were selected for combination. The AUC for NLR+PNI, NLR+RDW and PNI+RDW were 0.825 (95% CI 0.761 to 0.877), 0.854 (95% CI 0.794 to 0.902) and 0.806 (95% CI 0.741 to 0.861), respectively (figure 1). There were no significant differences in AUC for combined index and NLR (p=0.699, p=0.167 and p=0.975, respectively).

Table 4.

Discriminatory ability of inflammation-based markers for predicting mortality in patients with AP

| Index | AUC (95% CI) | p Value* | Cut-off† | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | +LR | −LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort | |||||||

| NLR | 0.804 (0.738 to 0.859) | <0.001 | 16.64 | 82.4 | 75.6 | 3.38 | 0.23 |

| CRP | 0.774 (0.706 to 0.833) | <0.001 | 162.2 mg/L | 76.5 | 73.8 | 2.92 | 0.32 |

| RDW | 0.769 (0.700 to 0.828) | <0.001 | 13.0% | 94.1 | 54.3 | 2.06 | 0.11 |

| PNI | 0.769 (0.701 to 0.828) | <0.001 | 33.1 | 58.8 | 88.4 | 5.08 | 0.47 |

| LMR | 0.744 (0.674 to 0.806) | <0.001 | 1.40 | 82.4 | 57.3 | 1.93 | 0.31 |

| Validation cohort | |||||||

| NLR | 0.851 (0.790 to 0.900) | <0.001 | 16.64 | 85.7 | 73.8 | 3.27 | 0.19 |

| CRP | 0.753 (0.683 to 0.815) | <0.001 | 162.2 mg/L | 71.4 | 65.2 | 2.06 | 0.44 |

| RDW | 0.708 (0.635 to 0.773) | 0.001 | 13.0% | 85.7 | 50.0 | 1.71 | 0.29 |

| PNI | 0.791 (0.724 to 0.848) | <0.001 | 33.1 | 42.9 | 88.4 | 3.70 | 0.65 |

| LMR | 0.677 (0.603 to 0.745) | 0.015 | 1.40 | 78.6 | 49.4 | 1.55 | 0.43 |

| Overall | |||||||

| NLR | 0.823 (0.780 to 0.861) | <0.001 | 16.64 | 83.9 | 74.4 | 3.27 | 0.22 |

| CRP | 0.762 (0.714 to 0.805) | <0.001 | 162.2 mg/L | 74.2 | 69.8 | 2.46 | 0.37 |

| RDW | 0.742 (0.693 to 0.786) | <0.001 | 13.0% | 90.3 | 49.7 | 1.80 | 0.19 |

| PNI | 0.781 (0.734 to 0.822) | <0.001 | 33.1 | 51.6 | 88.4 | 4.46 | 0.55 |

| LMR | 0.710 (0.660 to 0.757) | <0.001 | 1.40 | 77.4 | 54.0 | 1.68 | 0.42 |

*The p value is comparing the AUC with 0.5.

†The cut-off values were derived from a training cohort.

−LR, negative likelihood ratio; +LR, positive likelihood ratio; AP, acute pancreatitis; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CRP, C reactive protein; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Figure 1.

ROC curves analysis for predicting mortality by NLR and combined markers in the estimation cohort. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Demographics and laboratory findings in estimation and validation cohorts

bmjopen-2016-013206supp_table.pdf (183.6KB, pdf)

For NLR, the optimal cut-off value for mortality prediction was 16.64, with a sensitivity of 82.4% and specificity of 75.6%. RDW had the highest sensitivity (94.1%) and lowest −LR (0.11), so it was a reliable predictive index for excluding mortality in patients with AP. PNI had the highest specificity (88.4%) and +LR (5.08), so it was most suitable for use as a confirmed index among the indexes assessed.

In the validation cohort, AUCs for NLR, CRP, RDW, PNI and LMR were 0.851 (95% CI 0.790 to 0.900), 0.753 (95% CI 0.683 to 0.815), 0.708 (95% CI 0.635 to 0.773), 0.791 (95% CI 0.724 to 0.848) and 0.677 (95% CI 0.603 to 0.745), respectively. There were no significant differences in AUC for NLR, CRP, RDW, PNI and LMR between the estimation and validation cohorts (p=0.477, p=0.809, p=0.437, p=0.782 and p=0.455, respectively).

Survival analysis

Patients with AP were stratified into groups by cut-off values. Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate the relationships between inflammation-based prognostic markers and overall survival of patients with AP (figure 2A−E). Elevated NLR (p<0.001), CRP (p<0.001) and RDW (p<0.001) were associated with increased probability of death. Conversely, decreased PNI (p<0.001) and LMR (p=0.001) were associated with decreased overall survival.

Figure 2.

Relationship between inflammation-based prognostic markers and overall survival in patients with acute pancreatitis. A, B, C, D and E show the relationship between NLR, CRP, RDW, PNI and LMR, and overall survival in patients with acute pancreatitis, respectively. CRP, C reactive protein; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width.

According to the cut-off values for the factors, low NLR (≤16.64), low CRP (≤162.2 mg/L), low RDW (≤13.0%), high PNI (>33.1) and high LMR (>1.40) were selected as references. Univariate analysis and Cox regression revealed that age (p<0.001), amylase (p=0.001), NLR (p<0.001), PNI (p<0.001), CRP (p<0.001), RDW (p<0.001) and LMR (p=0.002) were associated with AP mortality (table 5). These factors were evaluated using multivariate Cox regression. Age (HR=4.039, 95% CI 1.873 to 8.713, p<0.001), NLR (HR=4.726, 95% CI 1.627 to 13.726, p=0.004), CRP (HR=3.503, 95% CI 1.534 to 7.999, p=0.003), RDW (HR=3.139, 95% CI 1.277 to 7.714, p=0.013) and PNI (HR=2.641, 95% CI 1.248 to 5.590, p=0.011) were independently associated with mortality of AP (table 5).

Table 5.

Prognostic factors of overall survival in patients with acute pancreatitis by univariate and multivariate analyses

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Age (>63 vs ≤63 years) | 5.384 (2.653 to 10.925) | <0.001 | 4.039 (1.873 to 8.713) | <0.001 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 0.767 (0.372 to 1.579) | 0.471 | ||

| Amylase (>618 vs ≤618 U/L) | 3.544 (1.699 to 7.526) | 0.001 | 2.173 (0.965 to 4.891) | 0.061 |

| NLR (>16.64 vs ≤16.64) | 13.130 (5.041 to 34.205) | <0.001 | 4.726 (1.627 to 13.726) | 0.004 |

| CRP (>162.2 vs ≤162.2 mg/L) | 6.127 (2.740 to 13.701) | <0.001 | 3.503 (1.534 to 7.999) | 0.003 |

| RDW (>13.0% vs ≤13.0%) | 4.929 (2.022 to 12.017) | <0.001 | 3.139 (1.277 to 7.714) | 0.013 |

| PNI (≤33.1 vs >33.1) | 6.912 (3.414 to 13.991) | <0.001 | 2.641 (1.248 to 5.590) | 0.011 |

| LMR (≤1.40 vs >1.40) | 3.797 (1.636 to 8.813) | 0.002 | 1.036 (0.403 to 2.659) | 0.942 |

CRP, C reactive protein; LMR, lymphocyte–monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; RDW, red cell distribution width.

Discussion

AP is an inflammatory disease, with mortality arising mainly from organ failure or infected pancreatic necrosis.4 Our study estimated the prognostic value of various inflammation-based prognostic markers for predicting mortality of AP. According to classifications of AUC,20 21 the ability of the NLR to predict mortality was good, while those of PNI, CRP, RDW and LMR were fair. Cox regression analysis revealed that age, NLR, PNI, CRP and RDW were independently associated with mortality of AP. Additionally, PNI, CRP and RDW were independently associated with the occurrence of SAP in patients with AP.

NLR, CRP, RDW and PNI are inexpensive, convenient and readily available in clinical settings. From examination of AUC, NLR had the best performance. With an NLR>16.64 at the time of admission, the risk of dying increased 3.726-fold compared with NLR≤16.64. RDW was the most reliable marker for excluding death in patients with AP, owing to its lowest −LR (0.11). PNI had the highest specificity (88.4%) and +LR (5.08), so it was most suitable to be a confirmed index among the indexes assessed. However, fluctuations in the NLR and CRP can be influenced by the use of antibiotics; therefore, NLR and CRP are not suitable for patients undergoing intensive use of antibiotics. Similarly, blood transfusion and parenteral nutrition may affect RDW and PNI, respectively, so the predictive value of RDW and PNI in these patients was discounted.

In AP, inflammation propagates and promotes tissue destruction via activation of a cascade of inflammatory cytokines, proteolytic enzymes and oxygen-free radicals.19 22 Neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes are the three main types of white cell counts (WCC). Neutrophils play a key role in the development of local tissue destruction and systemic complications of SAP.23 Depletion of neutrophils has been associated with an improved prognosis of AP.23 The percentage of immature neutrophilic granulocytes might be used clinically as a simple early predictor of an adverse outcome in SAP.24 Additionally, recent studies revealed that the extent of lymphopaenia was associated with disease severity.25–27 Lymphopaenia has been reported to have independent prognostic value for some diseases,19 26–29 including AP. Takeyama et al28 found that impairment of cellular immunity caused by peripheral lymphocyte apoptosis was linked to the subsequent development of infectious complications in AP. Monocytes produce various cytokines and inflammatory mediators that further amplify inflammatory cell recruitment into the pancreas as well as distant organs such as the lungs.30 Similar to neutrophils, a protective effect was also found by depleting macrophages in a mouse model of AP.31 Theoretically, NLR and LMR, which combine two opposing parameters, should be more accurate than either parameter alone. We found that the NLR had the greatest prognostic value of all the factors we evaluated. It is, however, important to apply the NLR with caution in clinical settings. Broad-spectrum antibiotics with good tissue penetration, which are essential medicines in the treatment of SAP, can affect WCC by reducing inflammation. Thus, the prognostic value of NLR in AP is uncertain if the effect of antibiotic treatment is not taken into account.32 For this reason, the neutrophil and lymphocyte counts used in this study were from the first complete blood cell count conducted during the emergency visit. We confirmed that the enrolled patients were untreated at that time; consequently, our results are most likely applicable to untreated patients. Unlike for the NLR, the predictive ability of the LMR was only fair, and was not independently associated with overall survival in AP.

Serum albumin is a negative acute phase response reactant, and reflects the body's nutritional status. Albumin <25 g/L was an independent prognostic factor related to a poor prognosis of AP.33 Variation of albumin within 24 hours has been identified as a risk factor for a poor prognosis of critically ill patients in the early stages of SAP.34 The PNI, which includes serum albumin and lymphocyte count, is an independent predictor of poor overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.35 To the best of our knowledge, few studies have reported on the application of PNI for predicting mortality of AP, but we found that it was an independent prognostic factor, and was suitable as a confirmed marker.

Numerous studies have reported RDW as a strong independent prognostic factor in various diseases and conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer and critical illnesses.18 36–38 Our results are consistent with the study by Yao and Lv,18 who reported a significant association between RDW and mortality of patients with AP. Additionally, we found that RDW was most suitable as a reliable excluding marker among the markers we assessed. The mechanisms underlying the association between RDW and mortality in AP remain unclear. The obvious metabolic abnormalities in non-survivors of AP, including inflammation, oxidative stress, poor nutritional status and persistent organ failure, lead to deregulation of red blood cell homoeostasis involving both impaired erythropoiesis and abnormal red blood cell survival.38 RDW reflects these impairments in homoeostasis, but only further research can confirm this speculation.

The prognostic markers evaluated in this study are direct or combined markers of systemic inflammation that are based on routine, inexpensive and readily available laboratory tests. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the prognostic value of these markers for predicting mortality in patients with AP simultaneously. Additionally, suitable excluding and identifying markers were found.

Some potential limitations of the study should be noted. Although we have taken special care to avoid sources of bias and confounding, some potential bias may still exist in this retrospective, single-centre study. Information available at the beginning of the study may have affected the selection of the study participants, although the medical records and laboratory data were collected separately by two people. The reasons for incomplete medical records or why patients were lost to follow-up (n=23) are not known. These patients were excluded from the analyses. As a result, a larger prospective study is needed to validate the results. Second, only the first set of admission blood results were investigated. Since factors change with time, they should be surveyed in the future because of the rapid onset of inflammation. Third, the typical prediction models, such as the APACHE II score, should be included in future research. Fourth, for better validity, +LR should be near 10, and −LR should be 0.2. Unfortunately, no marker examined had perfect +LR and −LR simultaneously. Therefore, the markers should be selected with caution based on particular needs. The marker with the higher +LR was more suitable to confirm death, while the marker with the lower −LR was more suitable to exclude death. Appropriate judgement based on the available information will be more reliable; however, these markers are still valuable based on their acceptable AUC. Finally, we only described the association of each of the predictors with mortality of AP; the underlying mechanisms need to be investigated.

In conclusion, we found that age, NLR, PNI, CRP and RDW were independently associated with overall survival of AP. NLR had the best overall performance, RDW was suitable as a reliable marker to exclude death, and PNI was a good predictive marker for death. When applying these markers, any possible influence from therapy should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Edanz Group for helping edit the English of the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: RG and YL designed the experiments. RG and YL contributed to the data collection. YZ conducted the data analysis. YL, RG and LF wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This work was financially supported by grants from the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY15H190002) and the Department of Education Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (Y201330146).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision. The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires two of the following three features: and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013;62:102–11. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maheshwari R, Subramanian RM. Severe acute pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis. Crit Care Clin 2016;32:279–90. 10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Boni M et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: a review of the interventions. Int J Surg 2016;28(Suppl 1):S163–71. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M et al. Organ failure and infection of pancreatic necrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:813–20. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger EP, Forsmark CE, Layer P et al. Determinant-based classification of acute pancreatitis severity: an international multidisciplinary consultation. Ann Surg 2012;256:875–80. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256f778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papachristou GI, Muddana V, Yadav D et al. Comparison of BISAP, Ranson's, APACHE-II, and CTSI scores in predicting organ failure, complications, and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:435–41; quiz 42 10.1038/ajg.2009.622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mounzer R, Langmead CJ, Wu BU et al. Comparison of existing clinical scoring systems to predict persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1476–82; quiz e15–6 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bezmarevic M, Mirkovic D, Soldatovic I et al. Correlation between procalcitonin and intra-abdominal pressure and their role in prediction of the severity of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2012;12:337–43. 10.1016/j.pan.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang CJ, Chen J, Phillips AR et al. Predictors of severe and critical acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:446–51. 10.1016/j.dld.2014.01.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunziker S, Celi LA, Lee J et al. Red cell distribution width improves the simplified acute physiology score for risk prediction in unselected critically ill patients. Crit Care 2012;16:R89 10.1186/cc11351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita A, Onoda H, Imai N et al. Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2012;107:988–93. 10.1038/bjc.2012.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teng JJ, Zhang J, Zhang TY et al. Prognostic value of peripheral blood lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with solid tumors: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2016;9:37–47. 10.2147/OTT.S94458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L, Lou Y, Chen Y et al. Prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:1034–40. 10.1111/ijcp.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith RA, Bosonnet L, Raraty M et al. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent significant prognostic marker in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg 2009;197:466–72. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D et al. An inflammation-based prognostic score (mGPS) predicts cancer survival independent of tumour site: a Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Br J Cancer 2011;104:726–34. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D et al. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2633–41. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zampieri FG, Ranzani OT, Sabatoski V et al. An increase in mean platelet volume after admission is associated with higher mortality in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care 2014;4:20 10.1186/s13613-014-0020-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao J, Lv G. Association between red cell distribution width and acute pancreatitis: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004721 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suppiah A, Malde D, Arab T et al. The prognostic value of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in acute pancreatitis: identification of an optimal NLR. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:675–81. 10.1007/s11605-012-2121-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem 1993;39:561–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 3: receiver operating characteristic plots. BMJ 1994;309:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felderbauer P, Muller C, Bulut K et al. Pathophysiology and treatment of acute pancreatitis: new therapeutic targets--a ray of hope? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2005;97:342–50. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue J, Sharma V, Habtezion A. Immune cells and immune-based therapy in pancreatitis. Immunol Res 2014;58:378–86. 10.1007/s12026-014-8504-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu L, Chen G, Xia Q et al. Use of band cell percentage as an early predictor of death and ICU admission in severe acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 2010;57:1543–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts—rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy 2001;102:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Jager CP, van Wijk PT, Mathoera RB et al. Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Crit Care 2010;14:R192 10.1186/cc9309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Tulzo Y, Pangault C, Gacouin A et al. Early circulating lymphocyte apoptosis in human septic shock is associated with poor outcome. Shock 2002;18:487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeyama Y, Takas K, Ueda T et al. Peripheral lymphocyte reduction in severe acute pancreatitis is caused by apoptotic cell death. J Gastrointest Surg 2000;4:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pezzilli R, Billi P, Beltrandi E et al. Circulating lymphocyte subsets in human acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 1995;11:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay C, Imrie CW, Baxter JN. Mononuclear phagocyte activation and acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1996;219:32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saeki K, Kanai T, Nakano M et al. CCL2-induced migration and SOCS3-mediated activation of macrophages are involved in cerulein-induced pancreatitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1010–20.e9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Binnetoglu E, Akbal E, Gunes F et al. The prognostic value of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in acute pancreatitis is controversial. J Gastrointest Surg 2014;18:885 10.1007/s11605-013-2435-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalvez-Gasch A, de Casasola GG, Martin RB et al. A simple prognostic score for risk assessment in patients with acute pancreatitis. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:e43–8. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Zhang ZW, Wang B et al. Relationship between early serum albumin variation and prognosis in patients with severe acute pancreatitis treated in ICU. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2013;44:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinato DJ, North BV, Sharma R. A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI). Br J Cancer 2012;106:1439–45. 10.1038/bjc.2012.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lappegard J, Ellingsen TS, Vik A et al. Red cell distribution width and carotid atherosclerosis progression. The Tromso Study. Thromb Haemost 2015;113:649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekler A, Tenekecioglu E, Erbag G et al. Relationship between red cell distribution width and long-term mortality in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Anatol J Cardiol 2015;15:634–9. 10.5152/akd.2014.5645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A et al. Red blood cell distribution width: A simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2015;52:86–105. 10.3109/10408363.2014.992064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Demographics and laboratory findings in estimation and validation cohorts

bmjopen-2016-013206supp_table.pdf (183.6KB, pdf)