Abstract

Objectives

This study investigated the prevalence and correlates of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) use in Taiwan.

Design and setting

We studied a nationally representative random sample in the 2015 Taiwan Adult Smoking Behavior Survey.

Participants

This study included 26 021 participants aged 15 years or older (51% women, 79% non-smokers, 16% aged 15–24 years), after excluding 31 persons (0.1%) who had missing information on e-cigarette use.

Primary outcome measures

The prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes was calculated in the overall sample and by smoking status (current, former and never) or age (15–24, 25–44 and ≥45 years). We performed multivariable log-binomial regression to assess correlates of ever having used e-cigarettes among all participants and separately for subgroups by smoking status and age.

Results

Approximately 3% of all participants had ever used e-cigarettes. The prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes was high in current smokers (14%) and people aged 18–24 years (7%). E-cigarette use was particularly common in people aged 15–24 years who were current (49–52%) or former (22–39%) smokers. Ever having used e-cigarettes was positively associated with tobacco smoking (adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR): 21.5, 95% CI 15.4 to 29.8, current smokers; aPR: 8.3, 95% CI 15.2 to 13.1, former smokers), younger age and high socioeconomic status. Age remained a significant factor of ever having used e-cigarettes across smoking status groups. Among non-smokers, men had a 2.4-fold (95% CI 1.5 to 3.8) greater prevalence of e-cigarette use than women.

Conclusions

E-cigarette use was uncommon in the general population in Taiwan, but prevalence was high among smokers and young people. This study highlights challenges that e-cigarettes pose to tobacco control, which warrant high priority action by policymakers and public health professionals. E-cigarette regulations should focus on young people.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, Smoking and tobacco, Young adult, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH, Taiwan

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study with a nationally representative sample in Taiwan investigating the prevalence and correlates of e-cigarette use.

This was a cross-sectional survey with only one question that assessed ever having used e-cigarettes. Respondents may have under-reported e-cigarette use. Information about specific e-cigarette products, such as their flavour or design, was unavailable.

The time trend and change of e-cigarette use warrant further research.

The relatively small sample size of adolescents and young adults may restrict the application of our findings.

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes or vapour) have changed tobacco smoking behaviours and contemporary concepts of tobacco control. E-cigarettes deliver a nicotine aerosol by heating a solution that usually contains nicotine, propylene glycol, glycerol and flavouring agents.1 2 E-cigarette use has increased substantially,3 4 especially among young adults in most,4–11 but not all, countries.12 Marketed as alternatives to conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes lower users' exposure to toxins by delivering nicotine without burning tobacco.1 13 14 However, data on the long-term health effects of chemicals in e-cigarette aerosols are lacking.2 13 15 16 Furthermore, concerns have been raised about diacetyl and acetyl propionyl in solutions of certain e-cigarette products.17

E-cigarettes may hinder tobacco control efforts. E-cigarette use has been associated with a lower likelihood of quitting smoking among cigarette smokers,18 and might be a gateway for non-smokers to initiate tobacco smoking,1 particularly among adolescents or young adults.1 19–21 The prevalence of e-cigarette use may differ between smokers and non-smokers and between younger and older adults. A meta-analysis study has demonstrated that smoking status is a determinant of e-cigarette use,22 and the behaviour of e-cigarette use is also greatly influenced by age.10 22 It is essential for public health professionals and policymakers to understand the epidemiology of e-cigarette use and relevant correlates within each subgroup of age and smoking status.

E-cigarette use is increasing in the USA,6 Canada5 and Europe.7 Epidemiological studies in Asia have suggested a relatively low prevalence of e-cigarette use: prevalence in Hong Kong was 2.3% in 2014,11 and <1% in Indonesia and Malaysia in 2011.12

No laws in Taiwan are specifically designed to regulate e-cigarettes and the Taiwan government has not yet approved any nicotine-containing e-cigarettes. Only nicotine-free products can be sold legally, but these nicotine-free products cannot claim to be smoking cessation aids, and cannot be sold in a form resembling tobacco products. There are no published studies on e-cigarette use in Taiwan. Such research is essential for tobacco control and policy design.

The current study used a 2015 Taiwanese national survey of individuals aged 15 years and older to: (1) describe the epidemiology of e-cigarette use overall and by smoking status; and (2) investigate the prevalence of e-cigarette use in relation to socioeconomic characteristics in each subgroup of smoking status and age.

Methods

Taiwan Adult Smoking Behaviour Survey data

The Adult Smoking Behavior Survey, 2015 was an annual computer-assisted telephone surveillance conducted by the Health Promotion Administration in Taiwan, to survey a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalised individuals aged 15 years or older.23 The sampling frame was the residential telephone directory of 25 administrative districts. The survey sample size for each district was probability proportional to the district population size. Within each district, the random digit dialling principle was followed to select the telephone number; the prefix of the telephone numbers was selected first, and the last two digits of the selected area codes were randomly selected. Once the call was picked up, an individual aged 15 years or older was randomly selected to answer the survey. A computer-assisted telephone interviewing system was used to elicit participants' demographic data, as well as information about the smoking behaviours, environmental tobacco smoke exposure and awareness of tobacco control interventions. At least 1068 telephone interviews were conducted for each administrative district except for Lianjiang County, where only 300 interviews were conducted due to its small population size. The response rate of the 2015 Adult Smoking Behavior Survey was 70.7%, resulting in 26 052 respondents who participated in the survey. Nationally representative estimates were produced using sampling weight, based on the sex, age, education level and population size of each district in 2014. Informed consent was waived.

Variables

Ever having used e-cigarettes

Ever versus never having used e-cigarettes was assessed by the question: ‘Have you ever used an e-cigarette?’. Of 26 052 respondents, 31 (0.1%) who provided the answer ‘I don't know’ to the question were excluded, resulting in 26 021 respondents eligible for calculation of the prevalence of e-cigarette use.

Smoking status

Smoking status categories included: never smoker, former smoker and current smoker. Current smokers were defined as those who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes and reported smoking every day, or some days, in the 30 days preceding the interview. People who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes but had not smoked in the past 30 days were designated as former smokers. Never smokers comprised people who had never smoked or had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes. Ever smokers included former and current smokers.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

Demographic variables included age in category (15–17, 18–24, 25–44, 45–64 and ≥65 years), sex, marital status and residing in municipal areas (six major cities: Kaohsiung, New Taipei, Taichung, Tainan, Taipei and Taoyuan). Socioeconomic variables included education level, employment status and monthly household income (in New Taiwan Dollar, NTD).

Statistical analysis

We described demographic characteristics for the overall population and for three smoking subgroups: current, former and never smokers. Distributions of characteristics by smoking status were compared by χ2 test. We estimated the prevalence and 95% CIs of ever using e-cigarettes by demographic and socioeconomic variables for the overall population and for each smoking subgroup. Prevalence ratios and 95% CIs were estimated using multivariable log-binomial regression models for prevalence of ever using e-cigarettes in relation to sociodemographic factors in the overall population and by three smoking subgroups. These regression models included smoking status (for the entire population only), age groups, sex, residing in municipal area, marital status, education level and monthly household income. We also performed stratified analyses by smoking status (ever or never smokers) and age groups to investigate factors associated with e-cigarette use for each subgroup. The final sample for regression modelling included 25 112 respondents after we excluded 909 respondents who had missing information on age (n=766), marital status (n=159) or education level (n=106).

Analyses were conducted in STATA V.12.1 (StataCorp. 2011, College Station, Texas, USA). The ‘svy’ command was used for sampling weight and ‘svy: proportion’ command was used to estimate 95% CIs of e-cigarette use prevalence.

Results

Sample characteristics

The study sample included 26 021 respondents after excluding 31 persons (0.1%) who had missing information on e-cigarette use. Among the study sample, approximately half were women, and the majority were aged 25–64 years (67.7%), resided in municipalities, were married, were employed and had an education of high school or above (table 1). Approximately one-third of respondents self-reported a monthly household income between NTD 20 001 and 60 000 and one-third NTD 60 001 or more. Demographics of never smokers differed from current and former smokers. Compared with current or former smokers, never smokers were more likely to be women (63.0% vs 8.4–10.1%), younger than 25 years (18.9% vs 2.0–6.6%), reside municipally (43.5% vs 38.4–40.1%), be unmarried (44.3% vs 24.2–41.6%) and have a college or higher education level (46.0% vs 26.6–31.7%) (all p<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents in Taiwan Adult Smoking Behavior Survey, 2015, overall and by smoking status

| Smoking status |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire population (n=26 021) |

Current smokers (n=2573) | Former smokers (n=2817) | Never smokers (n=20 621) | ||

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p Value |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| 15–17 | 958 (3.7) | 13 (0.4) | 3 (0.1) | 942 (4.7) | |

| 18–24 | 1894 (12.0) | 107 (6.2) | 24 (1.9) | 1763 (14.2) | |

| 25–44 | 6376 (33.4) | 799 (44.5) | 337 (20.3) | 5239 (33.3) | |

| 45–64 | 10 792 (34.3) | 1218 (39.4) | 1406 (50.3) | 8166 (31.5) | |

| ≥65 | 5235 (13.6) | 404 (8.3) | 988 (24.9) | 3839 (13.0) | |

| Missing | 766 (2.9) | 32 (1.2) | 59 (2.5) | 672 (3.3) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 14 398 (50.9) | 281 (10.1) | 204 (8.4) | 13 907 (63.0) | |

| Male | 11 623 (49.2) | 2292 (89.9) | 2613 (91.6) | 6714 (37.0) | |

| Residing in municipal area | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 16 369 (57.5) | 1698 (61.6) | 1830 (59.9) | 12 834 (56.5) | |

| Yes | 9652 (42.5) | 875 (38.4) | 987 (40.1) | 7787 (43.5) | |

| Married | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 9238 (42.0) | 955 (41.6) | 593 (24.2) | 7685 (44.3) | |

| Yes | 16 624 (57.4) | 1609 (58.2) | 2206 (75.2) | 12 805 (55.0) | |

| Missing | 159 (0.6) | 9 (0.2) | 18 (0.6) | 131 (0.7) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||

| Middle school or below | 7468 (27.0) | 808 (32.5) | 980 (35.1) | 5674 (25.0) | |

| High school | 7728 (30.5) | 976 (40.8) | 833 (32.5) | 5914 (28.6) | |

| College or above | 10 719 (42.1) | 785 (26.6) | 989 (31.7) | 8944 (46.0) | |

| Missing | 106 (0.4) | 4 (0.1) | 15 (0.6) | 86 (0.4) | |

| Employed | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 12 947 (44.4) | 837 (26.0) | 1405 (41.4) | 10 700 (47.8) | |

| Yes | 13 074 (55.6) | 1736 (74.0) | 1412 (58.6) | 9921 (52.2) | |

| Monthly household income (NTD) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤20 000 | 3882 (11.9) | 385 (11.1) | 540 (15.9) | 2954 (11.6) | |

| 20 001–60 000 | 8785 (33.7) | 951 (38.7) | 905 (33.4) | 6926 (33.0) | |

| 60 001–100 000 | 4899 (19.9) | 475 (18.8) | 515 (19.2) | 3909 (20.2) | |

| ≥100 001 | 3584 (13.8) | 382 (15.7) | 431 (15.4) | 2771 (13.3) | |

| Unknown | 4871 (20.7) | 380 (15.8) | 426 (16.1) | 4061 (22.0) | |

E-cigarette use in the overall population

The prevalence of ever using e-cigarettes in the total population was 2.7% (95% CI 2.5% to 3.0%; table 2): highest among current smokers (14.2%, 95% CI 12.4% to 16.0%) and below 1.0% among never smokers. Participants aged 18–24 years had the highest prevalence (6.5%, 95% CI 5.2% to 7.9%) compared with people of other age groups. Overall, men (4.6%) had a greater prevalence than women (0.9%); however, among current smokers, men and women appeared to have a similar prevalence of e-cigarette use (14.1% in men and 15.3% in women). Participants with a monthly household income above NTD 100 001 (4.5%) also had a higher prevalence of e-cigarette use, compared with those with a lower monthly household income (0.8–3.6%).

Table 2.

Prevalence (95% CI) of ever having used e-cigarettes, overall and by smoking status, among participants in Taiwan Adult Smoking Behavior Survey, 2015

| Entire population (n=26 021) |

Current smokers (n=2573) |

Former smokers (n=2817) |

Never smokers (n=20 621) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (95% CI) |

Prevalence (95% CI) |

Prevalence (95% CI) |

Prevalence (95% CI) |

|||||

| Ever having used e-cigarettes | 2.7 | (2.40 to 2.99) | 14.2 | (12.38 to 16.02) | 3.2 | (2.23 to 4.19) | 0.8 | (0.59 to 0.92) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 15–17 | 2.2 | (1.15 to 3.19) | 52.4 | (21.99 to 82.87) | 22.4 | (0.00 to 64.28) | 1.5 | (0.67 to 2.32) |

| 18–24 | 6.5 | (5.16 to 7.91) | 49.3 | (38.52 to 60.11) | 39.1 | (17.20 to 61.03) | 2.9 | (1.99 to 3.91) |

| 25–44 | 3.8 | (3.12 to 4.39) | 16.8 | (13.64 to 19.92) | 7.3 | (3.90 to 10.74) | 0.6 | (0.39 to 0.88) |

| 45–64 | 1.5 | (1.20 to 1.82) | 8.1 | (6.23 to 10.01) | 1.6 | (0.81 to 2.36) | 0.1 | (0.06 to 0.24) |

| ≥65 | 0.4 | (0.21 to 0.58) | 3.1 | (1.16 to 4.95) | 0.6 | (0.15 to 1.06) | 0.1 | (0.00 to 0.16) |

| Missing | 0.2 | (0.00 to 0.49) | 2.6 | (0.00 to 7.75) | 0.8 | (0.00 to 2.30) | n/a | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 0.9 | (0.66 to 1.09) | 15.3 | (10.05 to 20.58) | 7.7 | (2.78 to 12.67) | 0.4 | (0.24 to 0.52) |

| Male | 4.6 | (4.03 to 5.13) | 14.1 | (12.14 to 16.01) | 2.8 | (1.83 to 3.76) | 1.4 | (1.01 to 1.78) |

| Residing in municipal area | ||||||||

| No | 2.4 | (2.09 to 2.80) | 12.3 | (10.17 to 14.35) | 3.1 | (1.88 to 4.27) | 0.6 | (0.42 to 0.81) |

| Yes | 3.0 | (2.54 to 3.54) | 17.3 | (14.00 to 20.62) | 3.4 | (1.75 to 5.07) | 0.9 | (0.64 to 1.24) |

| Married | ||||||||

| No | 4.0 | (3.44 to 4.60) | 19.1 | (15.79 to 22.49) | 8.3 | (4.94 to 11.64) | 1.4 | (1.05 to 1.76) |

| Yes | 1.7 | (1.46 to 2.03) | 10.6 | (8.68-12.58) | 1.6 | (0.92 to 2.28) | 0.2 | (0.14 to 0.34) |

| Missing | 1.0 | (0.00 to 2.40) | 21.8 | (0.00 to 49.30) | n/a | n/a | ||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Middle school or below | 1.2 | (0.76 to 1.65) | 6.6 | (3.94 to 9.25) | 0.6 | (0.00 to 1.33) | 0.2 | (0.02 to 0.34) |

| High school | 3.7 | (3.04 to 4.26) | 16.9 | (13.84 to 19.95) | 3.7 | (1.90 to 5.49) | 0.6 | (0.33 to 0.80) |

| College or above | 3.0 | (2.52 to 3.44) | 19.4 | (15.72 to 23.08) | 5.7 | (3.37 to 7.96) | 1.2 | (0.87 to 1.52) |

| Missing | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||

| Employed | ||||||||

| No | 1.6 | (1.26 to 1.91) | 10.8 | (7.92 to 13.68) | 2.5 | (1.16 to 3.79) | 0.7 | (0.43 to 0.91) |

| Yes | 3.6 | (3.12 to 4.04) | 15.4 | (13.15 to 17.62) | 3.7 | (2.34 to 5.12) | 0.8 | (0.60 to 1.07) |

| Monthly household income (NTD) | ||||||||

| ≤20 000 | 0.8 | (0.39 to 1.19) | 5.4 | (2.48 to 8.37) | 0.8 | (0.00 to 2.00) | 0.1 | (0.00 to 0.19) |

| 20 001–60 000 | 2.3 | (1.79 to 2.73) | 10.9 | (8.22 to 13.55) | 2.6 | (1.20 to 4.00) | 0.6 | (0.31 to 0.82) |

| 60 001–100 000 | 3.6 | (2.87 to 4.32) | 18.8 | (14.44 to 23.10) | 4.1 | (1.67 to 6.57) | 1.2 | (0.71 to 1.73) |

| ≥100 001 | 4.5 | (3.50 to 5.57) | 23.3 | (17.49 to 29.07) | 2.1 | (0.54 to 3.73) | 1.3 | (0.75 to 1.88) |

| Unknown | 2.4 | (1.76 to 3.05) | 14.0 | (9.23 to 18.82) | 6.8 | (2.87 to 10.73) | 0.6 | (0.32 to 0.95) |

Current and former smokers were more likely than never smokers to report ever having used e-cigarettes (table 3). Participants younger than 45 years had a greater prevalence ratio of ever using e-cigarettes relative to the 45–64 years age group, after adjusting for smoking status, sex, residing in municipal areas and other socioeconomic variables. Ever using e-cigarette was also associated with not being currently married, having a college or higher education and monthly household income ≥NTD60 001. Sex, employment status or residing in municipal areas was not associated with ever having used e-cigarettes.

Table 3.

Adjusted prevalence ratios for ever having used e-cigarettes, overall and by tobacco smoking status, in Taiwan, 2015

| Entire population (n=25 112) |

Ever smokers (n=5276) |

Never smokers (n=19 843) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smokers | 1.0 | (Reference) | n/a | n/a | ||

| Former smokers | 8.3 | (5.21 to 13.1) | n/a | n/a | ||

| Current smokers | 21.5 | (15.4 to 29.8) | n/a | n/a | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 15–17 | 4.4 | (2.53 to 7.68) | 7.0 | (3.71 to 13.4) | 8.5 | (2.96 to 24.1) |

| 18–24 | 5.2 | (3.73 to 7.26) | 6.1 | (4.24 to 8.67) | 10.7 | (4.11 to 28.1) |

| 25–44 | 2.1 | (1.57 to 2.81) | 2.4 | (1.75 to 3.23) | 2.7 | (1.21 to 5.80) |

| 45–64 | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| ≥65 | 0.4 | (0.22 to 0.66) | 0.3 | (0.18 to 0.56) | 0.5 | (0.09 to 3.03) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| Male | 1.3 | (0.96 to 1.87) | 1.0 | (0.70 to 1.36) | 2.4 | (1.48 to 3.80) |

| Residing in municipal area | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| Yes | 1.2 | (0.94 to 1.41) | 1.1 | (0.90 to 1.45) | 1.4 | (0.91 to 2.19) |

| Married | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| Yes | 0.7 | (0.54 to 0.89) | 0.7 | (0.50 to 0.84) | 0.6 | (0.32 to 1.13) |

| Education level | ||||||

| Middle school or below | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| High school | 1.5 | (0.97 to 2.30) | 1.5 | (0.97 to 2.42) | 0.7 | (0.19 to 2.28) |

| College or above | 1.6 | (1.04 to 2.51) | 1.4 | (0.90 to 2.31) | 1.1 | (0.32 to 4.05) |

| Employed | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| Yes | 0.9 | (0.70 to 1.17) | 1.0 | (0.72 to 1.29) | 1.3 | (0.73 to 2.25) |

| Monthly household income (NTD) | ||||||

| ≤60 000 | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) | 1.0 | (Reference) |

| ≥60 001 | 1.6 | (1.22 to 1.97) | 1.5 | (1.12 to 1.94) | 1.8 | (1.09 to 3.09) |

| Unknown | 1.1 | (0.81 to 1.50) | 1.2 | (0.86 to 1.73) | 0.9 | (0.45 to 1.70) |

PR, prevalence ratio.

E-cigarette use by smoking status

Stratified by smoking status, age remained associated with ever having used e-cigarettes, with a high prevalence among people aged 24 years or younger. For example, the prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes was 49.3% (95% CI 38.5% to 60.1%) among current smokers aged 18–24 years and 39% among former smokers of the same age (table 2). Compared with people aged 45–64 years, those aged 18–24 years had a 6-fold to 10-fold higher prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes, irrespective of smoking status (table 3). Among current and former smokers, men and women had a similar prevalence ratio of ever having used e-cigarettes; yet among never smokers, men were more than twice as likely as women to self-report ever having used e-cigarettes. Associations between ever having used e-cigarettes and socioeconomic variables were not observed in smoking subgroups, except that education in current or former smokers and monthly household income in current smokers were each associated with ever having used e-cigarettes.

Associations of e-cigarette with other characteristics by age and different smoking status

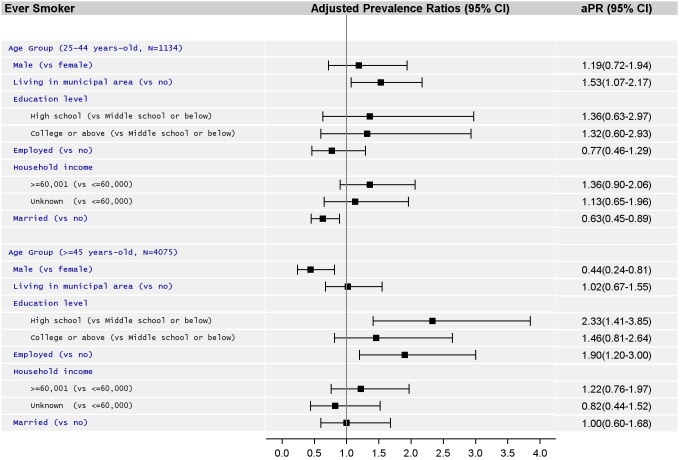

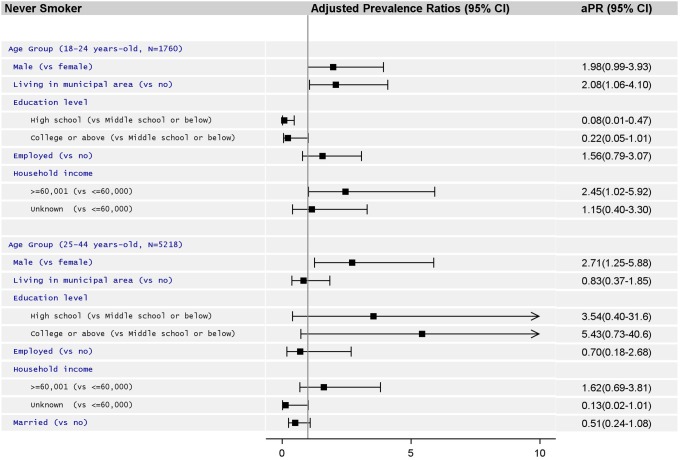

Ever having used e-cigarettes in association with age and smoking status prompted us to perform analyses stratified by three age groups (18–24, 25–44, ≥45 years) in ever smokers and in never smokers (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence ratio (95% CI) for e-cigarette use among ever smokers aged 25–44 years and 45 years or older.

Figure 2.

Prevalence ratio (95% CI) for e-cigarette use among never smokers aged 18–24 and 25–44 years.

Among ever smokers aged 25–44 years, marriage was associated with a lower prevalence of ever using e-cigarettes while those who lived in a municipal area had a greater prevalence (figure 1). Ever smoking men aged 25–44 years were less likely to self-report ever using e-cigarettes, which was not observed in other subgroups. Among never smokers aged 18–24 years, having a higher education level was associated with a decreased prevalence of ever using e-cigarettes, while living in a municipal area and having a higher household income were associated with increased prevalence (figure 2). Non-smoking men aged 25–44 years were 2.71 times more likely than women aged 25–44 years to ever use e-cigarettes. We did not perform the stratified analysis for ever smokers aged 18–24 years due to the small sample size. Results of never smokers aged 45 years or older were all non-significant (see online supplementary table S1).

Prevalence of e-cigarette use among age groups with different smoking status

bmjopen-2016-014263supp_table.pdf (259.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

In 2015, 2.7% of a nationally representative sample of Taiwan residents aged 15 years or older reported that they had ever used e-cigarettes. This prevalence was similar to that of Hong Kong (2.3% in 2014)11 and other Asian countries,12 but lower than the rate of 12.6% in the USA in 2014.6 Smoking status was the main determinant of ever having used e-cigarettes. Similar to countries where e-cigarette use is common,6 7 the prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes was <5% among individuals who were never and former smokers. In current smokers, the prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes was 14.2% in Taiwan, lower than the prevalence among smokers in Europe (20.3%, 2012),7 Australia (23.7%, 2013) and the UK (43.3%, 2013).8 The low prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes in Taiwan could be partly due to the relatively low tobacco smoking rates (30% in men and 4% in women, 2015)24 and a restricted e-cigarette market. Of note, the prevalence among young smokers in Taiwan was as high as that in the western countries: 38–50% of former and current smokers aged 15–24 years had ever used e-cigarettes, suggesting that young adults in Taiwan who have ever smoked tend to experiment with e-cigarettes.6 7 The high prevalence in the young population signals the need for regulations in Taiwan and worldwide.

E-cigarette may create nicotine dependency and initiate tobacco smoking among individuals who never smoked, particularly in adolescents.21 Among individuals aged 15–17 years in this study, up to 50% of smokers and 1.5% of individuals who never smoked had ever used e-cigarettes. These findings suggested that ∼49 000 smoking and 12 100 non-smoking adolescents have ever used e-cigarettes in Taiwan, given the reported smoking rate of 10.4%23 among 900 000 adolescents aged 15–17 years in 2015.25 More importantly, a prospective cohort of non-smoking adolescents has shown a 16% increase in initiation of tobacco smoking after 12 months among individuals who have ever used e-cigarettes (25% vs 9%).19 We estimate that 2000 adolescents in Taiwan may potentially initiate tobacco smoking. E-cigarette regulations and public education regarding nicotine dependency, particularly targeting adolescents, will be essential for tobacco control.

E-cigarette policies and regulations vary around the world. According to the Institute for Global Tobacco Control, e-cigarette sales are banned in 26 countries and there are age or other restrictions on their purchase in 38 countries.26 In Taiwan, several existing laws apply to e-cigarettes based on their nicotine content or shape; however, regulations are not applicable to e-cigarettes that contain no nicotine, claim no therapeutic properties or do not resemble cigarettes. Some concerns have been raised. First, the safety of chemicals in aerosols or solutions remains to be established.2 13 15 Second, e-cigarette use in public may weaken the effect of smoke-free policies,1 20 decrease the quitting motivation of smokers1 and potentially diminish the denormalisation of smoking.1 Impacts of e-cigarette use on tobacco smoking in populations with a low smoking prevalence, such as Taiwan, warrant prospective investigation.

E-cigarette use is more prevalent among people with high socioeconomic status in Asia,12 but not in Europe.7 Likewise, people in Taiwan with higher education levels or high household incomes, especially former and current cigarette smokers, are more likely to self-report ever using e-cigarettes. This pattern is consistent with the observation that people with high socioeconomic status tend to adopt new technology or knowledge quickly. In addition, our study suggests that women and men who have ever smoked had a similar likelihood of trying e-cigarettes, although men had a higher rate than women overall.

This study reported the prevalence of ever having used e-cigarettes in a nationally representative sample in Taiwan. Previous studies have mostly reported the prevalence of e-cigarette use within specific regions. With a larger sample size, we were able to report prevalence stratified by smoking status and age groups. This study has some notable limitations. First, information about specific e-cigarette products, such as their flavour, content, solution or design, was unavailable. Second, the relatively small sample size of adolescents and young adults may limit the generalisation of these findings. Third, this was a cross-sectional survey with only one question that assessed ever having used e-cigarettes. Respondents may have under-reported e-cigarette use.

E-cigarettes may pose some challenges to tobacco control. For example, the correlates of ever having used e-cigarettes differed by smoking status and age and seemed to vary by country. Regulations of e-cigarettes should be based on country-specific research. Furthermore, e-cigarettes may serve as a gateway to initiating tobacco smoking in the young population.19 In this study, 1.5% of never smokers aged 15–17 years in Taiwan, ∼12 100 adolescents, had ever used e-cigarettes. They may be susceptible to tobacco smoking.

Conclusion and public health implications

This national representative study in Taiwan suggests that people with higher education level and income are more likely to use e-cigarettes. Among smokers, women have a prevalence of using e-cigarettes similar to or even greater than that of men. The overall rate of ever having used e-cigarettes in Taiwan is lower than that in western countries; however, adolescents and young adults have the highest prevalence of ever using e-cigarettes—almost half of the ever-smokers aged 15–24 years reported having tried e-cigarettes. The emergence of e-cigarettes may have raised new challenges for tobacco control. Public health administrators and policy developers need to implement preventive measures against nicotine dependence among e-cigarette users, especially in the younger population. Future investigations of regular e-cigarette use, changes in tobacco smoking behaviours among e-cigarette users as well as underlying reasons for high prevalence of e-cigarette use among young adults are needed to guide public policy.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to drafts and approved the final version of the paper. H-CC and P-YC conceived the study and were in charge of the major work of manuscript writing. Y-WT and M-NS contributed to data acquisition, led the study design and revised the article for important intellectual content. Y-TW undertook the data analysis and contributed to results interpretation. H-CC, P-YC and Y-TW wrote the article. All authors had full access to all of the data and take responsibility for its integrity and accuracy in the analysis; P-YC is the guarantor of this manuscript on behalf of his coauthors. Imad Sawaya, MS, provided language editing and proofreading.

Funding: National Yang-Ming University received research funding from the tobacco health and welfare surcharges by the Health Promotion Administration for the project titled “International Collaborative Project for the Evaluation of Medical Services for Smoking Cessation (G1031227-105)”.

Disclaimer: The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect the official policy of the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. The study sponsor had no role in the study design, data analysis or interpretation and the researchers were independent of the sponsor in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of National Yang-Ming University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Electronic nicotine delivery systems|Report by WHO. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Sixth session Moscow: Russian Federation, 13–18 October 2014. http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6_10-en.pdf. (accessed 17 Aug 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation 2014;129:1972–86. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King BA, Patel R, Nguyen KH et al. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:219–27. 10.1093/ntr/ntu191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM et al. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1195–202. 10.1093/ntr/ntu213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid JL, Rynard VL, Czoli CD et al. Who is using e-cigarettes in Canada? Nationally representative data on the prevalence of e-cigarette use among Canadians. Prev Med 2015;81:180–3. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:715–19. 10.1093/ntr/ntv237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vardavas CI, Filippidis FT, Agaku IT. Determinants and prevalence of e-cigarette use throughout the European Union: a secondary analysis of 26 566 youth and adults from 27 Countries. Tob Control 2015;24:442–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yong HH, Borland R, Balmford J et al. Trends in E-Cigarette awareness, trial, and use under the different regulatory environments of Australia and the United Kingdom. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1203–11. 10.1093/ntr/ntu231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinnunen JM, Ollila H, El-Amin Sel T et al. Awareness and determinants of electronic cigarette use among Finnish adolescents in 2013: a population-based study. Tob Control 2015;24:e264–70. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll Chapman SL, Wu LT. E-cigarette prevalence and correlates of use among adolescents versus adults: a review and comparison. J Psychiatr Res 2014;54:43–54. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang N, Chen J, Wang MP et al. Electronic cigarette awareness and use among adults in Hong Kong. Addict Behav 2016;52:34–8. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palipudi KM, Mbulo L, Morton J et al. Awareness and current use of electronic cigarettes in Indonesia, Malaysia, Qatar, and Greece: findings from 2011–2013 Global adult tobacco surveys. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:501–7. 10.1093/ntr/ntv081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng T. Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2014;23(Suppl 2):ii11–17. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J et al. Associations between E-Cigarette type, frequency of use, and quitting smoking: findings from a longitudinal online panel survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1187–94. 10.1093/ntr/ntv078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown CJ, Cheng JM. Electronic cigarettes: product characterisation and design considerations. Tob Control 2014;23(Suppl 2):ii4–10. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etter JF, Bullen C. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette users. Addict Behav 2014;39:491–4. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farsalinos KE, Kistler KA, Gillman G et al. Evaluation of electronic cigarette liquids and aerosol for the presence of selected inhalation toxins. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:168–74. 10.1093/ntr/ntu176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:116–28. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA 2015;314:700–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bostean G, Trinidad DR, McCarthy WJ. E-Cigarette use among never-smoking California students. Am J Pub Health 2015;105:2423–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman BN, Apelberg BJ, Ambrose BK et al. Association between electronic cigarette use and openness to cigarette smoking among US young adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:212–18. 10.1093/ntr/ntu211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang M, Wang JW, Cao SS et al. Cigarette smoking and electronic cigarettes use: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:1 10.1155/2016/7014857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare R.O.C. (Taiwan). Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) 2015. Taipei Taiwan. 2016. http://tobacco.hpa.gov.tw/Content.aspx?MenuId=580&CID=29701 (accessed 16 Aug 2016).

- 24.Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare R.O.C. (Taiwan). Taiwan Tobacco Control Annual Report 2015, Taipei, Taiwan, 2016. http://health99.hpa.gov.tw/media/public/pdf/21806.pdf (accessed 16 Aug 2016).

- 25.Department of Statistics, Ministry of the Interior R.O.C. (Taiwan). Statistical yearbook of interior 2015 Yearly Bulletin of Interior Statistics. Taipei Taiwan. 2016 http://statis.moi.gov.tw/micst/stmain.jsp?sys=100 (accessed 16 Aug 2016).

- 26.Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Country laws regulating e-cigarettes: a policy scan. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2016. http://globaltobaccocontrol.org/node/14052 (accessed 16 Aug 2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Prevalence of e-cigarette use among age groups with different smoking status

bmjopen-2016-014263supp_table.pdf (259.1KB, pdf)