Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to explore determinants of second pregnancy and underlying reasons among pregnant Chinese women.

Design

The study was a population-based cross-sectional survey.

Setting

16 hospitals in 5 provinces of Mainland China were included.

Participants

A total of 2345 pregnant women aged 18 years or above were surveyed face to face by investigators between June and August 2015.

Main outcome measures

The pregnancy statuses (first or second pregnancy) and reasons for entering second pregnancy.

Results

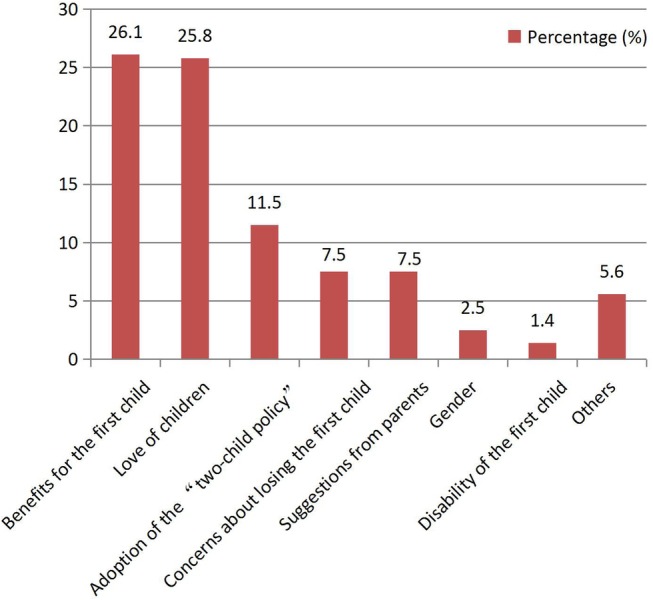

A total of 1755 (74.8%) and 590 (25.2%) women in their respective first and second pregnancies were enrolled in this study. The most common self-reported reasons for entering second pregnancy among participants included the benefits to the first child (26.1%), love of children (25.8%), adoption of the 2-child policy (11.5%), concerns about losing the first child (7.5%) and suggestions from parents (7.5%). Pregnant women with low (prevalence ratio (PR) 1.96; 95% CI 1.62 to 2.36) and moderate education level (PR 1.97; 95% CI 1.65 to 2.36) were more likely to have a second pregnancy than their higher educated counterparts. Income was inversely associated with second pregnancy. However, unemployed participants (PR 0.79; 95% CI 0.66 to 0.95) were less likely to enter a second pregnancy than those employed. Women with moderate education were 3 times more likely to have a second child following the ‘2-child policy’ than the low education level subgroup.

Conclusions

1 in every 4 pregnant women is undergoing a second pregnancy. The benefits of the firstborn or the love of children were the key drivers of a second pregnancy. Low socioeconomic status was positively associated with a second pregnancy as well. The new 2-child policy will have an influence on China's demographics.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH, SOCIAL MEDICINE, REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study includes a large number of participants living in five provinces in China and a face-to-face interview.

This study has implications in the implementation and enforcement of China's new universal two-child policy.

The main limitation is the relatively small number of participants from a rural area, which requires cautious interpretations of the study results, especially among rural women.

Introduction

Owing to the one-child policy, China has experienced low birth rates for three decades. Recent data indicated that the overall birth rate of the Chinese population declined from 2.106% in 1990 to 1.237% in 2014,1 which has led to long-term social and economic consequences.2 The one-child rule applies mainly to urban residents and government employees; thus, in rural areas, where ∼70% of the population resides, a second child is allowed after 5 years, especially if the firstborn is a girl.3 Along with the birth rate decline, rapid population ageing is becoming a public health problem in China. The percentage of people over 65 years of age increased from 5.6% in 1990 to 10.1% in 2014.4 Urbanisation and rapid ageing resulted in various problems such as urban resources relocation, poor air quality and social insecurity.5 The increasing number of ‘empty nest’ elderly (who live alone unaccompanied by any family member) has created huge demands for healthcare and other related services.6 Furthermore, the labour force supply has been declining.

Fertility desire or intention is an important factor influencing fertility trends.7 Fertility intention is associated with the economic, social and cultural environment within which the fertility awareness is cultivated, including family needs, motivation, intention and preferences.8 Procreation conception is often influenced by family social status, educational factors and fertility intention, which changes in adulthood to manifest as decreased or increased intended family size.9 Fertility rate and reproductive number are low in developed countries, and these are affected by the conflict between individual will and family decisions.10 The fertility intention of having a second child largely depends on the number of sons in South Asia.11 Son preference is prevalent among the Chinese, especially in rural areas.12 However, this reality has been changing with improvements in the social security and educational systems, as well as the infrastructure. Under the influence of the family planning policy beginning in the 1970s, the fertility preference of son preference is not prevalent anymore.13

‘Selective two-child policy’ was introduced at the end of 2013, and it allowed couples nationwide to have a second child if either parent is an only child. On 29 October 2015, the Chinese government announced a new universal two-child policy, allowing all couples to have a second child, and cancelled the rewards for having only one child and the extended maternity leave. In the short term, the two-child policy may significantly boost the service sector development, which in turn may guide investments towards more efficient and profitable areas. Furthermore, the policy may raise the percentage of newborns, which in the long run will significantly increase housing demand and consumption.14

However, whether people in China will respond to the new two-child policy and have a second child remains unknown. Understanding the determinants and the reasons for having a second child is important in several aspects including the implementation of the new universal two-child policy and health service planning. Nevertheless, no studies on this focus have been conducted in China. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore second pregnancy determinants and main reasons for the second pregnancy by addressing three research questions as follows: (1) What is your main reason for the second pregnancy?; (2) What are the second pregnancy determinants among pregnant Chinese women?; (3)What are the factors that affect the main reason for the second pregnancy?

Methods

Research methods

The study design and methods have been reported previously.15–17 All pregnant women visiting 16 hospitals in Chongqing, Chengdu, Zunyi, Liaocheng and Tianjin between June and August 2015 were invited to participate. We excluded women with serious complications or cognitive disorders. Chongqing, Chengdu and Zunyi are in South China, whereas Liaocheng and Tianjin are in North China. A total of 2400 women participated in the study with a response rate of 97.76%. All participants provided written consent.

Measurements

Outcome variable: Pregnancy status (first or second pregnancy). The definition of second pregnancy is dependent on the outcome of the first pregnancy (ie, live birth).

Sociodemographic variables

Age was recoded into three categories: 18–25, 26–35 and 36–45 years. Participants were asked about their residence (urban/rural), family income per capita (<¥4500, ¥4500–¥9000 and >¥9000) and employment status (rural migrant workers/urban and rural unemployed, unemployed/industrial workers of non-agricultural registered permanent residence/individual business/business services staff/civil servants/senior manager and middle-level manager in large and medium enterprises/private entrepreneur/professionals/clerks/students/others). On the basis of the Chinese hospital ranking system, hospital capacity/quality rank was recorded as high, medium and low. Women were also asked about their ethnicity (Han or minority) and whether she or her husband was an only child. Marital status was categorised as unmarried, first marriage, remarried and divorced/widowed. Pregnancy was divided into three trimesters. Education level was categorised as low (junior middle school or below), medium (senior high school, vocational or technical secondary school) and high (university).

In the multivariable analysis for second pregnancy determinants, employment status was categorised as manual (rural migrant workers/industrial workers of non-agricultural registered permanent residence/business services staff), non-manual (individual business/civil servants/senior manager and middle-level manager in large and medium enterprises/private entrepreneur/professionals/clerk/and students), unemployed and others.

The study indicated the following second pregnancy reasons:

Benefits for the first child: benefit for the growth and the future of the first child.

Love of children: love children.

Adoption of the ‘two-child policy’: ‘two-child policy’ is the most second pregnancy reason.

Concerns about losing the first child: parents who have lost their only child are known as Shidu parents in China. They are worried about losing the first child.

Suggestions from parents: parents strongly recommend having a second child.

Gender: son preference or girl preference was included.

Disability of the first child: the first child is disabled. They would like to have a healthy child.

Others: other reasons are those that are not listed in the above seven reasons.

Statistical analyses

Participant characteristics were summarised using frequencies and percentages and presented with descriptive analyses (means, SDs and percentages). The χ2 tests were used to compare the categorical variables. A Poisson model was applied in the multivariate analysis to assess the factors associated with the second pregnancy. In the Poisson regression analysis, prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs were calculated. The choice of the method of Poisson model is justified because of the high prevalence of the outcome (second pregnancy).18 Seven multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the common reasons for entering a second pregnancy: (1) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘benefits for the first child’ for entering a second pregnancy; (2) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘love of children’ for entering a second pregnancy; (3) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘adoption of the two-child policy’ for entering a second pregnancy; (4) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘concerns of losing the first child’ for entering a second pregnancy; (5) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘suggestions from parents’ for entering a second pregnancy; (6) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘gender’ for entering a second pregnancy; and (7) multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the sociodemographic factors related to the key reason for ‘disability of the first child’ as a reason for entering a second pregnancy, respectively. We included sociodemographic variables (nationality, single child, husband was a single child, marital status, education level, residence, income, job, age and hospital capacity level) with ‘key reasons for entering second pregnancy’ as the dependent variable in the regression model with backward elimination to retain those factors that were still significant. All statistics were performed using two-sided tests, and statistical significance was considered at p<0.05. All data analyses were performed using statistical software (SAS V.9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

A total of 1755 (74.8%) and 590 (25.2%) women in their respective first and second pregnancies were enrolled, 19.8% of whom lived in urban areas. Among the women aged 26–35 years, 67.2% and 70.3% of them were in their first and second pregnancies, respectively. For high education level, we had 72.8% and 52.9% of the women in their first and second pregnancies, respectively. About half of the pregnant women or their husbands were an only child themselves. Among the women in their second pregnancy, 438 (74.2%) were visiting high capacity hospitals and 26.4% had a low education level (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants by number of pregnancy (n, %)

| Variable | First pregnancy | Second pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 1755 (74.8) | 590 (25.2) |

| Hospital capacity level | ||

| High | 1386 (79.0) | 438 (74.2) |

| Medium | 202 (11.5) | 109 (18.5) |

| Low | 167 (9.5) | 43 (7.3) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 546 (31.1) | 78 (13.2) |

| 26–35 | 1180 (67.2) | 415 (70.3) |

| 36–45 | 29 (1.7) | 97 (16.5) |

| Nationality | ||

| Han nationality | 1690 (96.3) | 562 (95.3) |

| Minority | 65 (3.7) | 28 (4.8) |

| Single child | ||

| No | 960 (54.7) | 339 (57.5) |

| Yes | 795 (45.3) | 251 (42.5) |

| Husband was a single child | ||

| No | 847 (48.3) | 325 (55.1) |

| Yes | 908 (51.7) | 265 (44.9) |

| Marital status | ||

| First marriage | 1678 (95.6) | 527 (89.3) |

| Unmarried | 36 (2.1) | 13 (2.2) |

| Remarried | 25 (1.4) | 45 (7.6) |

| Divorced or widowed | 16 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) |

| Education level | ||

| Low | 246 (14.0) | 156 (26.4) |

| Medium | 232 (13.2) | 122 (20.7) |

| High | 1277 (72.8) | 312 (52.9) |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 314 (17.9) | 151 (25.6) |

| Urban | 1441 (82.1) | 439 (74.4) |

| Income | ||

| Low | 428 (24.4) | 183 (31.0) |

| Medium | 759 (43.3) | 230 (39.0) |

| High | 568 (32.4) | 177 (30.0) |

| Employment | ||

| Rural migrant workers | 59 (3.4) | 59 (10.0) |

| Urban and rural unemployed, half of the unemployed | 423 (24.1) | 130 (22.0) |

| Industrial workers of a non-agricultural registered permanent residence | 38 (2.2) | 12 (2.0) |

| Individual business | 117 (6.7) | 82 (13.9) |

| Business services staff | 122 (7.0) | 33 (5.6) |

| Civil servants | 326 (18.6) | 72 (12.2) |

| Senior manager and middle-level manager in large and medium enterprises | 70 (4.0) | 26 (4.4) |

| Private entrepreneur | 56 (3.2) | 31 (5.3) |

| Professionals | 194 (11.1) | 50 (8.5) |

| Clerk | 112 (6.4) | 27 (4.6) |

| Students | 14 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) |

| Others | 224 (12.8) | 67 (11.4) |

Education level was categorised as ≤primary school, junior middle school (basic education), ≥a senior high school (including vocational/technical secondary school and junior college), (secondary education) and ≥senior college and university (higher education).

The multivariable logistic regression model showed that marital status, education, employment status, income, age and hospital capacity level were associated with a second pregnancy. Compared with first marriage women, remarried women were about three times more likely to enter a second pregnancy (PR 1.63; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.07). Pregnant women with low (PR 1.96; 95% CI 1.62 to 2.36) and medium education levels (PR 1.97; 95% CI 1.65 to 2.36) were more likely to enter a second pregnancy than their higher educated counterparts. Moreover, pregnant women with medium income (PR 0.83; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.97) were less likely to enter a second pregnancy than their low-income counterparts. Similarly, age was associated with increased likelihood of entering a second pregnancy: the PR for a second pregnancy was 2.51, 3.41 (95% CI 2.01 to 3.14) and 6.03 (95% CI 4.70 to 7.73) for those aged 18–25, 26–35 and 36–45 years, respectively. Compared with women with non-manual jobs, the unemployed women (PR 0.79; 95% CI 0.66 to 0.95) were less likely to have second pregnancies. Compared with those being registered in a low ranking hospital, pregnant women who were admitted to a medium ranking hospital were more likely to enter a second pregnancy (PR 1.43, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.91). Furthermore, rural residence does not contribute to a higher second pregnancy rate (table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted prevalence ratios for second pregnancy according to sociodemographic factors among pregnant women

| Parameter | PR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | |||

| Han nationality | 1 | ||

| Minority | 1.08 | 0.81 to 1.43 | 0.597 |

| Single child | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.12 | 0.97 to 1.29 | 0.122 |

| Husband was a single child | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.86 to 1.14 | 0.848 |

| Marital status | |||

| First marriage | 1 | ||

| Unmarried | 1.18 | 0.74 to 1.89 | 0.495 |

| Remarried | 1.63 | 1.29 to 2.07 | <0.0001* |

| Divorced or widowed | 0.65 | 0.30 to 1.43 | 0.284 |

| Education level | |||

| High | 1 | ||

| Low | 1.96 | 1.62 to 2.36 | <0.0001* |

| Medium | 1.97 | 1.65 to 2.36 | <0.0001* |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 1 | ||

| Urban | 0.89 | 0.75 to 1.046 | 0.154 |

| Income | |||

| Low | 1 | ||

| Medium | 0.83 | 0.71 to 0.97 | 0.022* |

| High | 0.88 | 0.73 to 1.05 | 0.16 |

| Job | |||

| Non-manual | 1 | ||

| Manual | 0.9 | 0.75 to 1.09 | 0.294 |

| Unemployed | 0.79 | 0.66 to 0.95 | 0.011* |

| Others | 0.99 | 0.79 to 1.24 | 0.939 |

| Age | |||

| 18–25 years old | 1 | ||

| 26–35 years old | 2.51 | 2.01 to 3.14 | <0.0001* |

| 36–45 years old | 6.03 | 4.70 to 7.73 | <0.0001* |

| Hospital capacity level | |||

| Low | 1 | ||

| High | 1.12 | 0.86 to 1.456 | 0.418 |

| Medium | 1.43 | 1.07 to 1.91 | 0.016* |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05).

PR, prevalence ratios.

Among the pregnant women who were having a second pregnancy, the common reasons for entering a second pregnancy included: benefits for the first child (26.1%), love of children (25.8%), adoption of the two-child policy (11.5%), concerns about losing the first child (7.5%), suggestions from parents (7.5%), gender (2.5%) and disability of the first child (1.4%; figure 1).

Figure 1.

The common reasons for entering a second pregnancy.

The multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated that women with high education were less likely to be influenced by parents than those with low education (OR 0.16; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.39). Mothers who were an only child themselves (OR 0.36; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.80) or those living in urban areas (OR 0.52; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.99) tend to be less concerned about losing the first child as a reason for having a second child than their counterparts. Compared with Han Chinese women, women with minority backgrounds were 2.67 times more likely to have a second child because of their love for children. Compared with the low education level group, women with medium education levels were three times more likely to have a second child in adoption of the ‘two-child policy’. Parents who were an only child themselves were less likely to report ‘love of children’ as a reason for having a second child than their counterparts (table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression model for main reasons of the second pregnancy according to sociodemographic factors

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suggestions from parents | |||

| Education level | |||

| Low education | 1.00 | ||

| Medium education | 1.00 | 0.49 to 2.04 | 0.993 |

| High education | 0.16 | 0.07 to 0.39 | <0.000* |

| Concerns about losing the first child | |||

| Single child | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.36 | 0.16 to 0.80 | 0.012* |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 1.00 | ||

| Urban | 0.52 | 0.27 to 0.99 | 0.047* |

| Love children | |||

| Nationality | |||

| Han nationality | 1.00 | ||

| Minority | 2.67 | 1.18 to 6.04 | 0.018* |

| Single child | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.54 | 0.35 to 0.83 | 0.005* |

| Husband was a single child | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.37 to 0.85 | 0.006* |

| Disability of the first child | |||

| Nationality | |||

| Han nationality | 1.00 | ||

| Minority | 6.82 | 1.31 to 35.57 | 0.023* |

| Adopting the ‘two-child policy’ | |||

| Education level | |||

| Low education | 1.00 | ||

| Medium education vs low education | 3.08 | 1.41 to 6.70 | 0.005* |

| High education vs low education | 1.56 | 0.76 to 3.22 | 0.225 |

| Others | |||

| Nationality | |||

| Han nationality | 1.00 | ||

| Minority | 5.68 | 1.94 to 16.61 | 0.002* |

*Statistically significant (p<0.05).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study involving participants from five provinces in China, we found that one in every four pregnant women is entering a second pregnancy 1 year after the new second-child policy. Furthermore, low education and low income are positively associated with a second pregnancy among the respondents. Either parent being an only child was not associated with the likelihood of having a second child. The reasons for having a second pregnancy differ in sociodemographic factors.

The finding that only one in every four pregnant women is in their second pregnancy is beyond our expectation, given the large number of eligible women in China. The reasons for this result require further investigation. The rationale may be attributed to the ‘Demographic-Economic Paradox’, which states that economic development is the best contraceptive.19 Moreover, we hypothesise that changes in family size and high costs of education, housing and medical service are among the main motives for fewer women opting for a second pregnancy. Previous studies also show concern about ‘the costs of providing for children’ as a reason for not having a second child,20 given that parents traditionally pay for their children's education and housing. In some of the study areas, the cost of an apartment is almost 6.6 times in Sichuan province, 6.3 times in Chongqing, 5.1 times in Guizhou, 5.8 times in Shandong province and 10.0 times in Tianjin more than the average annual salary in 2015.21

One of the key findings of this study is the increased tendency of low socioeconomic status groups to have second pregnancies. Pregnant women with low and medium education levels were more likely to have second pregnancies than their higher educated counterparts. A previous study showed that women who graduated from college tend to have fewer children than those with high school degrees or lower education levels.22 Another study showed that although women with higher education were often expected to have more children than their less educated counterparts, the number of pregnancies was often less than in the low education level group.7 According to the literature,23 24 highly educated women were more frequently revising their birth intentions downwards of having more children than less educated women, especially when they were nearing the end of their fertile years. Given that the percentage of highly educated women has been increasing over time as their fertility birth rate has been declining in many European countries7 and in China, gaining more knowledge about the effect of education on fertility decision-making is of particular importance. Future research is required to determine the factors that affect fertility decision-making among highly educated women in China.

Compared with women with low income, those with medium income were less likely to have a second pregnancy. Low socioeconomic status groups were more likely to have a second pregnancy even if they are intensifying the poverty of life, with more pressure on feeding, healthcare, housing, education and pension after the second childbirth. A survey realised among women in two highly developed rural counties of China showed a negative association between income and number of children.25 This study found that poorer women tend to be more willing to have a second pregnancy, while higher socioeconomic status groups are less likely to give birth for a second time. This finding is averse to the quality promotion (especially in the aspect of education) of the entire population. In the past, the one-child policy implementation was difficult to implement in rural areas; however, the two-child policy may be challenging today and in the future in some developed areas and among high socioeconomic status groups. Future studies are necessary to address these potential problems. In China, the typical family structure is 4–2–1: four grandparents and two parents, with a single child who is expected to support both parents and grandparents.26 Owing to the typical family structure, husbands and wives need to support parents from both sides as they are raising their second child.

In this study, we found that living in a rural area does not contribute to a higher rate of second pregnancy. Previous studies showed that people in rural areas might be strongly influenced by traditional ideas; thus, women would be more affected by first child gender preference,12 in addition to the higher child mortality rate in rural areas compared with urban areas.2 Gender bias in family formation, such as sex-selective abortion, sex ratio imbalance and other phenomena, are well documented in China.27 However, under the influence of the family planning policy beginning in the 1970s, the fertility concept began to change with less focus or expectations of son preference.13 This study found that only 2.5% of respondents had a second child because of the firstborn's gender, which suggests that the fertility concept has changed in rural areas; as such, the difference in the ratio of the second child between rural and urban areas will be minimal.

This study found that age was associated with a greater likelihood of entering the second pregnancy. A high proportion of second pregnancy was seen among those aged 26–35 (70.3%) or 36−45 (16.5%) years. Possible reasons for the age of having a first child in China being on the rise may include economic development, the popularisation of superior education and higher employment pressures. Also, education and career were reported as important factors in the women's decisions to delay marriage and motherhood.28 Second, since the 1970s, when the family planning policy was implemented, most women who intended to have a second child were not allowed to do so. These women may have waited until the new two-child policy was implemented; that could be an explanation for so many older pregnant women.

This study was conducted only 1 year after the implementation of the new two-child policy ‘selective two-child policy’, which is a relatively short period for analysis. Many young women have no child or only one. Given the work and life pressures, child education concerns and so on, these women may be less willing to plan for a second pregnancy. The age at which women have their firstborn bears implications for schooling, labour force participation and overall family size. Compared with other western countries, the age of first pregnancy in China is lesser. Along with the USA, many other developed nations (eg, Italy, the Netherlands and Switzerland) have observed increases in average age at first pregnancy, with some countries averaging near 30 years of age.29 One concern about this phenomenon is the increased pregnancy risks associated with mother's older age. Furthermore, a previous study showed that many parents (35 years and older) may find child-rearing challenging (taking care of their infant, dealing with the issues of helping their adolescent children and taking care of their elderly parents) after the second childbirth.2

The only-child mother's desire to have a second baby is stronger than that of a non-only-child mother.13 Previous studies showed that fondness of the child, released pension pressure and family inheritance events are possible factors influencing an only-child mother to conceive the second child.17 Interestingly, an only-child parent was less likely to report love for children as a reason for having a second child than their counterparts. An only-child mother enjoyed love from parents alone; as such, they may also have the concept of taking comprehensive care of children ingrained deep in their minds, as well as the lack of suffering consciousness about losing a child.

An editorial concluded that in modern, economically developed China, the women's decisions tend to influence the size of Chinese families over the next generation more than the policymakers in Beijing.26 This study determined that only about 10% of the participants adopted the two-child policy. It also found that pregnant women with medium education levels were more likely to have a second pregnancy in accordance with the ‘two-child policy’ than pregnant women with low education levels. Further research studies are necessary to investigate how to enhance the acceptance and execution of the policy in the high socioeconomic status group.

This study includes limitations that should be further addressed. First, the reason behind the low proportion of women having a second pregnancy remains undetermined. Second, there may be a selection bias and the sample was not nationally representative. Not all pregnant women in the five cities attended the 16 selected hospitals. The sample consisted of pregnant women in five regions, namely Chongqing, Chengdu and Zunyi in South China, and Liaocheng and Tianjin in North China. In this study, city-fixed effects were not controlled in the regression models. City-fixed effects may exist, but we are not sure. Third, more than 90% of the respondents were Han Chinese; as such, the conclusion of this study may not apply to minorities; more than half of the respondents have high education levels. Thus, this study may be not applicable to low education level groups. Fourth, although we adjusted for several socioeconomic status-related variables (ie, residence, educational level and income), residual confounding can still affect the second pregnancy variable. Furthermore, we did not collect the information on the gender of the first child. Finally, only a small number of rural women were included in the study, and such an outcome may affect the representativeness of this population, requiring cautious interpretations of the study results, especially among rural women.

Conclusions

One in every four pregnant women is undergoing a second pregnancy. Women with low education and low income were more likely to have second pregnancies. Either parent being an only child was not associated with the likelihood of having a second child. Rural residence does not contribute to a higher second pregnancy rate. The new two-child policy will significantly influence the demographics in China. The findings have implications for the implementation and enforcement of China's new universal two-child policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the project sponsors, the Medjaden Academy and Research Foundation for Young Scientists and Summer Social Practice Project of School of Public Health and Management, Chongqing Medical University. They also thank team members for their support and contributions to this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Cesar Reis @drcesarreis

Contributors: All authors contributed to the overall conception and design of the study. XX contributed to the study design, data analysis, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. HaZ, YR, LW and YZ participated in the design of the study and helped draft the manuscript. MS, HuZ, LZ and CR contributed to the interpretation of study results and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project was supported by the Medjaden Academy and Research Foundation for Young Scientists (grant number MJR20150047). This study was also funded by the Summer Social Practice Project of School of Public Health and Management, Chongqing Medical University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (no. 2015008).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. China health and family planning statistical yearbook 2015. Beijing, China: Pecking Union Medical College Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong W, Xu DR, Caine ED. Challenges arising from China's two-child policy. Lancet 2016;387:1274 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30020-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J. Gender inequality, family planning, and maternal and child care in a rural Chinese county. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:695–708. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding QJ, Hesketh T. Family size, fertility preferences, and sex ratio in China in the era of the one child family policy: results from national family planning and reproductive health survey. BMJ 2006;333:371–3. 10.1136/bmj.38775.672662.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yufen T, Yu W. The population characteristics and problems in the process of China's urbanization. Popul Dev 2013;19:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. China country assessment report on ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2015. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/china-country-assessment/en/

- 7.Testa MR. On the positive correlation between education and fertility intentions in Europe: individual- and country-level evidence. Adv Life Course Res 2014;21:28–42. 10.1016/j.alcr.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Changhong Z. Logical conceptual model of child bearing ideology. J Nanjing Coll Popul Program Manag 2007;23:5–7+47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berrington A, Pattaro S. Educational differences in fertility desires, intentions and behaviour: a life course perspective. Adv Life Course Res 2014;21:10–27. 10.1016/j.alcr.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorbritz J. Germany: family diversity with low actual and desired fertility. Demogr Res 2008;19:557–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayaraman A, Mishra V, Arnold F. The relationship of family size and composition to fertility desires, contraceptive adoption and method choice in South Asia. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009;35:29–38. 10.1363/ifpp.35.029.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding W, Zhang Y. When a son is born. The impact of fertility patterns on family finance in rural China. China Econ Rev 2014;30:192–208. 10.1016/j.chieco.2014.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia Z. Fertility desire changes of Chinese after 1950s. Popul Econ 2009;04:24–28+33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiaobo Q. Two-child policy to balance demographics. China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2015-11/05/content_22374656.htm. (accessed 5 Nov 2015).

- 15.Wang L, Xu X, Baker P et al. Patterns and associated factors of caesarean delivery intention among expectant mothers in China: implications from the implementation of China's new National Two-Child Policy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:pii: E686 10.3390/ijerph13070686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu X, Rao Y, Abdullah AS et al. Preventive behaviours in avoiding indoor secondhand smoke exposure among pregnant women in China. Tob Control Published Online First: 18 Jul 2016. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053047 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu X, Liu S, Rao Y et al. Prevalence and sociodemographic and lifestyle determinants of anemia during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study of pregnant women in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:pii: E908 10.3390/ijerph13090908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barkat EK, Harbison SF, Robinson WC. Is development really the best contraceptive? A 20-year trial in Comilla district, Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Popul J 1990;5:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu F, Bao J, Boutain D et al. Online responses to the ending of the one-child policy in China: implications for preconception care. Ups J Med Sci 2016;14:227–34. 10.1080/03009734.2016.1195464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanghai E-house Institute. Ranking list of ratio of house price to income of 30 provinces of China. April 2016. http://www.yiju.org/news/2016517/n22721034.html

- 22.Yang Y, Morgan SP. How big are educational and racial fertility differentials in the U.S.? Soc Biol 2003;50:167–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iacovou M, Tavares LP. Yearning, learning, and conceding: reasons men and women change their childbearing intentions. Popul Dev Rev 2011;37:89–123. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liefbroer AC. Changes in family size intentions across young adulthood: a life-course perspective. Eur J Popul 2009;25:363–86. 10.1007/s10680-008-9173-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas NH, Mu A. Fertility and population policy in two counties in China 1980–1991. J Biosoc Sci 2000;32:125–40. 10.1017/S0021932000001255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun W, Gordon J, Pacey A. From one to two: the effect of women and the economy on China's One Child Policy. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2016;19:1–2 10.3109/14647273.2016.1168980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W. Son preference and educational opportunities of children in China— “I wish you were a boy!”. Gender Issues 2005;22:3–30. 10.1007/s12147-005-0012-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mother, 1970-2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews TJ, Hamilton BE. Delayed childbearing: more women are having their first child later in life. NCHS Data Brief 2009;21:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]