Abstract

Introduction

Overall, intra-arterial treatment (IAT) proved to be beneficial in patients with acute ischaemic stroke due to a proximal occlusion in the anterior circulation. However, heterogeneity in treatment benefit may be relevant for personalised clinical decision-making. Our aim is to improve selection of patients for IAT by predicting individual treatment benefit or harm.

Methods and analysis

We will use data collected in the Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands (MR CLEAN) trial to analyse the effect of baseline characteristics on outcome and treatment effect. A multivariable proportional odds model with interaction terms will be developed to predict the outcome for each individual patient, both with and without IAT. Model performance will be expressed as discrimination and calibration, after bootstrap resampling and shrinkage of regression coefficients, to correct for optimism. External validation will be conducted on data of patients in the Interventional Management of Stroke III trial (IMS III). Primary outcome will be the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at 90 days after stroke.

Ethics and dissemination

The proposed study will provide an internationally applicable clinical decision aid for IAT. Findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publications, conference presentations and in an online web application tool. Formal ethical approval was not required as primary data were already collected.

Trial registration numbers

ISRCTN10888758; Post-results and NCT00359424; Post-resultsc.

Keywords: ischaemic stroke, intra-arterial therapy, mechanical thrombectomy, prediction model, decision aid, personalised treatment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Multiple characteristics will be evaluated simultaneously to show clinically relevant heterogeneity in treatment benefit between patients.

Multivariable prediction modelling substantially increases statistical power compared with other approaches and is more robust, especially in small data sets.

We will use a relatively small cohort for the development of a prediction model.

Using a proportional odds model requires the assumption that the ORs are the same for each cut-off of the modified Rankin Scale.

Introduction

In 2015, five consecutive randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showed that intra-arterial treatment (IAT) improves functional outcome in patients with a proximal occlusion in the anterior circulation.1–6 This was a major breakthrough in the field, and IAT is now implemented in updated guidelines on acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) management.7

Ideally, IAT will be targeted at patients who are expected to have optimal benefit: personalised treatment. In this study protocol, we present seven steps for development and validation of a clinical decision aid to predict which individual patients with AIS will benefit most from IAT.8 9

Methods and analysis

Step 1: problem definition and data inspection

Problem definition

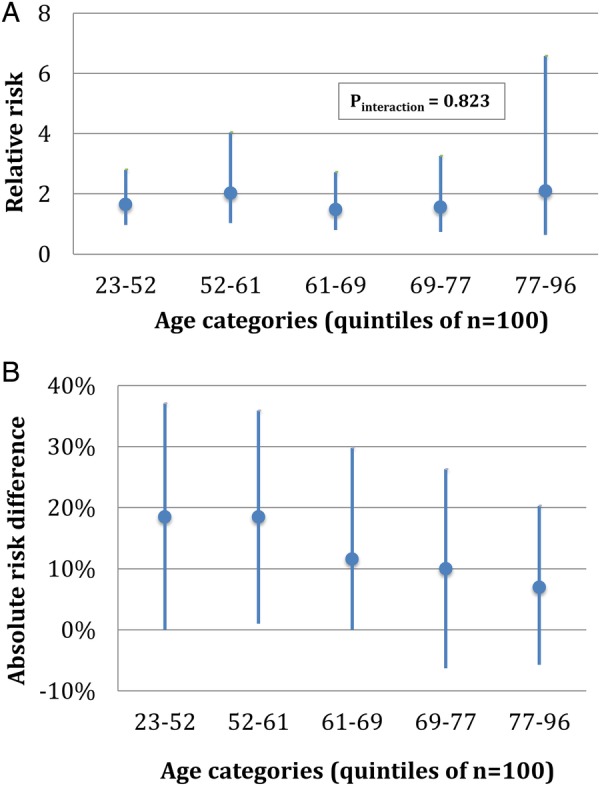

RCTs provide estimates of treatment effects for average patients. However, it is important to take potential heterogeneity of treatment effects into account. Clinically relevant differences in the absolute effect of a treatment can be caused by (1) differences in the relative treatment effect (predictive effects) and (2) differences in baseline risk on the outcome of interest (prognostic effects).10 11 For example, in the Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands (MR CLEAN) trial, there is no predictive effect of age; the relative treatment effect is constant across age subgroups.1 This is demonstrated by a non-significant test for interaction between age and treatment (figure 1A). However, variation in baseline risk on favourable outcome according to age results in a larger absolute treatment benefit in younger patients (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Relative risk (A) and absolute risk difference (B) for good functional outcome (mRS 0–2) in MR CLEAN sort by age. MR CLEAN, Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Conventional subgroup analyses are focused mainly on predictive effects and assess the effect of only one variable at a time. If predictive and prognostic effects of multiple characteristics are evaluated simultaneously in multivariable prediction modelling, it is likely that larger heterogeneity in treatment benefit between individual patients will be found. Our aim is to improve selection of patients for IAT by predicting treatment benefit or harm for individual patients with stroke.

Development data

We will use data of the MR CLEAN trial (n=500), which was a phase 3 multicentre clinical trial with randomised treatment group assignment, open-label treatment and blinded end point evaluation. IAT plus usual care (which could include intravenous administration of alteplase) was compared with usual care alone. IAT consisted of arterial catheterisation with a microcatheter to the level of occlusion and delivery of a thrombolytic agent, mechanical thrombectomy or both.1

Severity of stroke was assessed at baseline with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS; range 0–42). Baseline CT was evaluated with the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS; range 0–10). Baseline imaging (CT angiography) was used to determine the location of occlusion and to grade the quality of collateral flow to the ischaemic area with a four-point scale. Detailed information about the MR CLEAN trial can be found in the study protocol and the publication of the main results.1 12

End points of interest

The primary outcome will be the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death) at 90 days after stroke.13 We will provide estimates of treatment benefit as the absolute increase in probability on functional independence (defined as mRS 0–2) and survival (defined as mRS 0–5).

Step 2: coding of variables

As variables, we will use patient characteristics that are expected to predict outcome, or that are expected to interact with treatment, based on expert opinion and the recent literature (table 1). Non-linearity of continuous variables will be tested by comparing the two log likelihood of models with linear and restricted cubic spline functions.14

Table 1.

Patient characteristics that are expected to predict outcome (prognostic), or that are expected to interact with treatment (predictive)

| Per cent of data complete in MR CLEAN | Prognostic | Predictive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | |||

| Age6 15 | 100% | x | |

| Baseline NIHSS16 17 | 100% | x | |

| History of diabetes mellitus18 | 100% | x | |

| History of previous stroke19 | 100% | x | |

| History of atrial fibrillation20 | 100% | x | |

| Prestroke mRS score19 | 100% | x | |

| Systolic blood pressure21 | 100% | x | |

| IV treatment with alteplase22–24 | 100% | x | |

| Time from onset stroke to groin puncture25 26 | 100%* | x | x |

| Radiological | |||

| ASPECTS6 27 | 99.2% | x | |

| Location of intracranial occlusion on non-invasive vessel imaging28 29 | 99.8% | x | |

| Collateral score on CTA29 30 | 98.4% | x | x |

*Of patients undergoing intra-arterial treatment.

ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score; CTA, CT angiography; IV, intravenous; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; MR CLEAN, Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Timing of treatment is an essential predictor of outcome. Since time to randomisation was not a reliable indicator for time to treatment in the MR CLEAN trial and will not be applicable in clinical practice, we will use time from stroke onset to groin puncture. Since time to groin puncture is not observable in the control group, we will explore imputation approaches based on the correlation with time to randomisation. All other baseline variable values are more than 98% complete in the MR CLEAN data, so we choose simple imputation by the mean for continuous variables and simple imputation by the mode for categorical variables.

Steps 3 and 4: model specification and estimation

We will test the effect of variables on functional outcome and treatment effect with proportional odds regression modelling. All variables from table 1 will be tested for effect on outcome and interaction with treatment effect. Prognostic variables (main effects) and predictive variables (interaction effects) with a p value of 0.15 in univariable and multivariable analyses will be included in our final model. A p value of 0.15 was chosen to make the predictor selection less data driven and prevent overfitting.14 31 We will perform shrinkage of all regression coefficients with ridge regression to prevent overfitting of the model.14 Predicted probabilities for each of the mRS categories, with and without treatment, will be derived from the ordinal model. All statistical analyses will be performed within the computing environment R V.3.2.2 (The R Foundation)

Step 5: model performance

Model performance will be expressed in discrimination and calibration. Discrimination will be quantified with the c-statistic. The c-statistic is similar to the area under the curve for binary outcomes and estimates the probability that out of two randomly chosen patients, the patient with the higher predicted probability of a good outcome will indeed have a better outcome. Calibration refers to the agreement between predicted and observed risks and will be assessed graphically with validation plots, and expressed as calibration slope and an intercept. The calibration slope describes the relative overall effect of the variables in the validation sample, and is ideally equal to 1. The intercept indicates whether predictions are systematically too high or too low, and should ideally be 0.32 We will calculate a general c-statistic to express the performance of our ordinal model and additional calibration plots with specific c-statistics for the predictions of favourable functional outcome (mRS 0–2) and survival (mRS 0–5).

Step 6: model validity

The c-statistic will be internally validated with a bootstrap procedure (500 samples with replacement) to estimate the degree of optimism in parameter estimates.8 After penalisation of the regression coefficients, we will externally validate the model on data of patients in the Interventional Management of Stroke III trial (IMS III) with an occlusion in the anterior circulation on non-invasive vessel imaging.33 Coefficients of the final model will be fitted on the combined development and validation data sets.

After validation, we will assess whether the model can be used to discriminate between patients with low and high expected benefit by making individual predictions of outcome for all patients included in the development and validation data.

Step 7: model presentation

The final model will be digitally available for use in clinical practice, both for mobile devices and as a web application. It will provide predictions of all mRS categories for each individual patient, both with and without IAT.

Ethics and dissemination

Findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publications, conference presentations and in an online web application tool. Formal ethical approval was not required for this study as primary data were already collected.

Discussion

Compared with the current subgroup analyses on the effect of IAT, our modelling approach has multiple advantages. First, it accounts for the fact that patients have multiple characteristics that simultaneously affect the likelihood of treatment benefit.34 Thus, our model will show more clinically relevant heterogeneity in treatment benefit between patients. Second, a multivariable prediction model substantially increases statistical power to identify heterogeneity in treatment effects compared with other approaches.35 These include neural network and decision trees. We use regression modelling since it is considered more robust, especially in relatively small data sets.36 37

There are some differences between patients included in the MR CLEAN trial and the IMS III trial that may influence the external validity of our model. IMS III had different inclusion criteria, used older devices and older treatment paradigms than MR CLEAN. In order to overcome these limitations, we will use only those patients in IMS III with an occlusion in the intracranial anterior circulation on non-invasive vessel imaging. We will compare the baseline characteristics of the derivation and validation cohort and describe relevant differences that might lead to an underestimation or overestimation of the model performance. Interestingly, a substantial treatment effect in the IMS III patients with proven intracranial large vessel occlusion has been reported.38

Furthermore, even though the MR CLEAN trial has included most patients of the recent RCTs, the cohort remains relatively small for the development of a prediction model, especially for the selection of the main effect and interaction effects. We will reduce regression coefficients to prevent overfitting and also perform external validation. In the future, we will further validate and update our model in the pooled individual patient data of the Highly Effective Reperfusion evaluated in Multiple Endovascular Stroke Trials (HERMES) collaboration, harbouring data of all patients from recent randomised trials regarding IAT (over 1700 patients in total). Moreover, we aim to investigate the validity of our model predicting outcome after treatment in clinical practice. Our model will therefore be tested by applying it to recently treated patients in all Dutch neurovascular centres participating in the MR CLEAN Registry (mrclean-trial.org).

We will use a proportional odds model to analyse the full mRS score as outcome. Formally, this model requires the assumption that the ORs are the same for each cut-off of the mRS. However, previous studies have shown that even if the proportionality assumption is violated, proportional odds analysis is still more efficient than dichotomisation.39 In addition, all recent RCTs on the effect of IAT used the full mRS and analysed their results with proportional odds regression.

Conclusion

The proposed study will provide an internationally applicable clinical decision aid for the selection of patients for IAT. We consider this study an important next step towards personalised treatment of patients with AIS.

Footnotes

Contributors: MJHLM and EV were involved in literature search, study design, writing (authors contributed equally). BR and HFL were involved in study conception and design, and writing. EWS and DWJD were involved in study conception and design, and critical review of the manuscript. JPB, SDY, PK, OAB, YBWEMR, RJvO, WHvZ, CBLMM and AvdL were involved in study conception and critical review of the manuscript.

Competing interests: Erasmus MC received funds from Stryker®, Bracco Imaging® for consultations by DWJD. AMC received funds from Stryker® for consultations by CBLMM, YBWEMR and OAB. MUMC received funds from Stryker® and Codman® for consultations by WHvZ. JPB received study medication for intra-arterial tissue-type plasminogen activator supplied by Genentech. Catheters were supplied during early years of the IMS III trial by EKOS Corp, Concentric Medical, Cordis Neurovascular. He currently receives research monies to Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation Medicine from Genentech for Role on Steering Committee for A Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Activase (Alteplase) in Patients With Mild Stroke (PRISMS) trial. SDY research monies from Genentech for statistical role in the PRISMS trial. PKs department of Neurology received research support from Genentech, Inc for her role as lead principal investigator (PI) of the PRISMS trial and Penumbra, Inc for her role as neurology PI of the Assess the Penumbra System in the Treatment of Acute Stroke (THERAPY) trial; she has also received royalties from UpToDate, Inc and provided consultation for Grand Rounds Experts, St Jude’s and Biogen (DSMB).

Ethics approval: Medical and Ethical Review Committee Erasmus MC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D et al. . A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:11–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ et al. . Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1009–18. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell BC, Donnan GA, Lees KR et al. . Endovascular stent thrombectomy: the new standard of care for large vessel ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:846–54. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00140-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E et al. . Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2296–306. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A et al. . Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2285–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH et al. . Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016;387:1723–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J et al. . 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015;46:3020–35. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. New York: Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steyerberg EW, Vergouwe Y. Towards better clinical prediction models: seven steps for development and an ABCD for validation. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1925–31. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals: from randomised trials to presonalised medicine. London: Elsevier, 2007.

- 11.van Klaveren D, Vergouwe Y, Farooq V et al. . Estimates of absolute treatment benefit for individual patients required careful modeling of statistical interactions. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:1366–74. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fransen PS, Beumer D, Berkhemer OA et al. . MR CLEAN, a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke in the Netherlands: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:343 10.1186/1745-6215-15-343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC et al. . Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988;19:604–7. 10.1161/01.STR.19.5.604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E et al. . Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischaemic stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;379:2364–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60738-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broderick JP, Berkhemer OA, Palesch YY et al. . Endovascular therapy is effective and safe for patients with severe ischemic stroke: pooled analysis of interventional management of stroke III and multicenter randomized clinical trial of endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke in the Netherlands data. Stroke 2015;46:3416–22. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frankel MR, Morgenstern LB, Kwiatkowski T et al. . Predicting prognosis after stroke—a placebo group analysis from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Trial. Neurology 2000;55:952–9. 10.1212/WNL.55.7.952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luitse MJ, Biessels GJ, Rutten GE et al. . Diabetes, hyperglycaemia, and acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:261–71. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlinski M, Kobayashi A, Czlonkowska A et al. . Intravenous thrombolysis for stroke recurring within 3 months from the previous event. Stroke 2015;46:3184–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanák D, Herzig R, Král M et al. . Is atrial fibrillation associated with poor outcome after thrombolysis? J Neurol 2010;257:999–1003. 10.1007/s00415-010-5452-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr et al. . Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:870–947. 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581–7. 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E et al. . Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1317–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulder MJ, Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS et al. . Treatment in patients who are not eligible for intravenous alteplase: MR CLEAN subgroup analysis. Int J Stroke 2016;11:637–45. 10.1177/1747493016641969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P et al. . Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 2014;384:1929–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60584-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fransen PS, Berkhemer OA, Lingsma HF et al. . Time to reperfusion and treatment effect for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:190–6. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J et al. . Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. ASPECTS Study Group. Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score. Lancet 2000;355:1670–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02237-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puetz V, Dzialowski I, Hill MD et al. . Intracranial thrombus extent predicts clinical outcome, final infarct size and hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke: the clot burden score. Int J Stroke 2008;3:230–6. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2008.00221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan IYL, Demchuk AM, Hopyan J et al. . CT angiography clot burden score and collateral score: correlation with clinical and radiologic outcomes in acute middle cerebral artery infarct. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:525–31. 10.3174/ajnr.A1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkhemer OA, Jansen IG, Beumer D et al. . Collateral status on baseline computed tomographic angiography and intra-arterial treatment effect in patients with proximal anterior circulation stroke. Stroke 2016;47:768–76. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Harrell FE Jr et al. . Prognostic modelling with logistic regression analysis: a comparison of selection and estimation methods in small data sets. Stat Med 2000;19:1059–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR et al. . Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010;21:128–38. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM et al. . Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med 2013;368:893–903. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent DM, Rothwell PM, Ioannidis JP et al. . Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials 2010;11:85 10.1186/1745-6215-11-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S et al. . Multivariable risk prediction can greatly enhance the statistical power of clinical trial subgroup analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:18 10.1186/1471-2288-6-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Ploeg T, Austin PC, Steyerberg EW. Modern modelling techniques are data hungry: a simulation study for predicting dichotomous endpoints. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:137 10.1186/1471-2288-14-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Ploeg T, Nieboer D, Steyerberg EW. Modern modeling techniques had limited external validity in predicting mortality from traumatic brain injury. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;78:83–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demchuk AM, Goyal M, Yeatts SD et al. . Recanalization and clinical outcome of occlusion sites at baseline CT angiography in the Interventional Management of Stroke III trial. Radiology 2014;273:202–10. 10.1148/radiol.14132649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McHugh GS, Butcher I, Steyerberg EW et al. . A simulation study evaluating approaches to the analysis of ordinal outcome data in randomized controlled trials in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT Project. Clin Trials 2010;7:44–57. 10.1177/1740774509356580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]