Abstract

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department with lower respiratory tract infection and febrile neutropaenia. He was recently discharged following a 50-day hospital stay with newly diagnosed microscopic polyangiitis, complicated by pulmonary haemorrhage and severe renal dysfunction requiring renal replacement therapy, plasma exchange and immunosuppression (cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone). High risk of pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) led to an escalation in treatment from prophylactic to therapeutic oral co-trimoxazole, alongside broad-spectrum antibiotics. The patient suffered from severe and protracted hypoglycaemia, complicated by a tonic–clonic seizure 7 days after escalation to therapeutic co-trimoxazole. Endogenous hyperinsulinaemia was confirmed and was attributed to co-trimoxazole use. Hypoglycaemia resolved 48 hours after discontinuation of co-trimoxazole. PCP testing on bronchoalveolar lavage was negative. Owing to the prescription of heavy immunosuppression in patients with vasculitis and the subsequent risk of PCP warranting co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, we believe that the risk of hypoglycaemia should be highlighted.

Background

Drug-induced hypoglycaemia is a well-described phenomenon. A recent systematic review of 448 studies found an association with 164 drugs.1 The common non-diabetic drugs associated with hypoglycaemia are quinolones, pentamidine, quinine, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors and insulin-like growth factor.1 The link between hypoglycaemia and co-trimoxazole has previously been identified. The sulfamethoxazole component of co-trimoxazole (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) is similar in structure to a class of insulin secretagogues—the sulfonylureas. Hypoglycaemia induced by co-trimoxazole is thought to be secondary to hyperinsulinaemia (via stimulation of pancreatic β-cells), as suggested by elevation in levels of C peptide and serum insulin.2 Risk factors for this adverse effect include old age, renal dysfunction, prolonged fasting/malnutrition and excessive dosage.2

Published literature documenting this link include case reports involving the elderly population, chronic renal insufficiency, drug interactions in the diabetic and non-diabetic population, and the immunosuppressed population (HIV/AIDS and renal transplantation). We present a case of reversible co-trimoxazole-induced hypoglycaemia in a 69-year-old man with severe microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Case presentation

A 69-year-old man with a background of bronchiectasis with fibrotic change, previous tuberculosis and an effort tolerance of 100 yards originally presented with stage III acute kidney injury (AKI), streaky haemoptysis and tachycardia (120 bpm). His serum creatinine was 1083 µmol/L (<120) with urea 46 mmol/L (<6), bicarbonate 9 mmol/L (22–28) and haemoglobin 75 g/L.

He was diagnosed with MPA with lung and kidney involvement requiring a period of invasive positive pressure ventilation and renal replacement therapy in the critical care unit. Acute treatment consisted of plasma exchange (10 cycles), cyclophosphamide infusion (4 cycles) and methylprednisolone. Intravenous cyclophosphamide was switched to azathioprine because of repeated infections prior to discharge and a tapering course of prednisolone was prescribed. Discharge serum creatinine was 232 µmol/L.

Thirteen days after discharge, the patient re-presented with a lower respiratory tract infection, AKI and febrile neutropaenia (0.1×109/L). Initial management consisted of suspending azathioprine, increasing the dose of prednisolone, and prescribing piperacillin/tazobactam as per local guidelines. Pneumocystis pneumonia was suspected due to ongoing hypoxia, desaturation on exertion and worsening radiographic changes. This led to the prescription of therapeutic oral co-trimoxazole (2880 mg twice daily, adjusted for renal dysfunction) while awaiting bronchial washings.

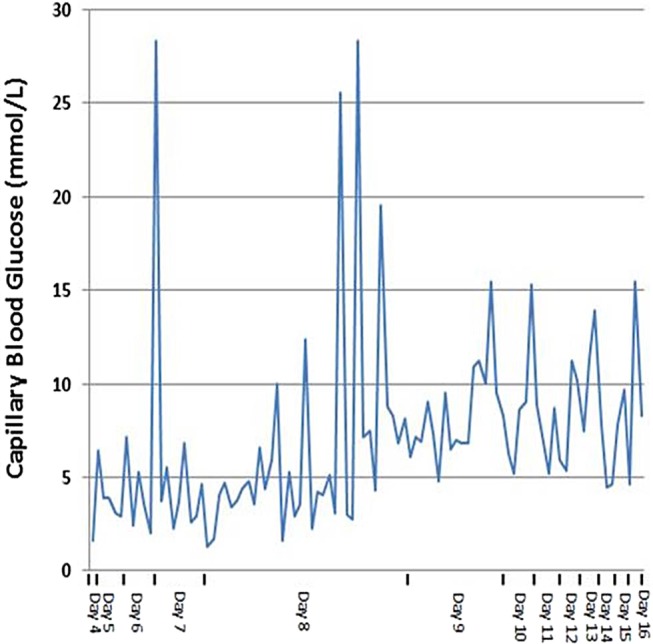

The first episode of symptomatic hypoglycaemia was noted 4 days after initiation (blood glucose 1.6 mmol/L; figure 1). Over the next 72 hours recurrent episodes were noted and a continuous 5% dextrose infusion was started.

Figure 1.

Changes in capillary blood glucose level from initial hypoglycaemic episode (day 4) to discharge (hypoglycaemic seizure—day 7, co-trimoxazole withdrawal—day 7).

After 7 days of oral co-trimoxazole the patient suffered a tonic–clonic seizure which terminated following administration of diazepam. Blood glucose was 3.1 mmol/L at the time of onset. Glycaemic control remained unstable dropping rapidly between boluses of 50 mL 50% dextrose and repeated doses of intramuscular glucagon. Co-trimoxazole was identified as a potential cause and was subsequently discontinued. Infusion of 20% dextrose was required to maintain blood glucose >7.0 mmol/L over the following 48 hours.

Investigations

Blood count and clinical chemistry, other than recovering neutropaenia, resolving AKI and raised inflammatory markers were unremarkable. Septic screen, pneumocystis PCR, atypical pneumonia serology, cytomegalovirus serology and influenza A/B PCR were negative. HIVp24 and hepatitis B/C serology were also negative.

Biochemistry confirmed drug-induced hyperinsulinaemia as the likely cause as shown below.

Blood glucose: <3.0 mmol/L

C peptide: 4250 pmol/L

Serum insulin: 690 pmol/L

Random cortisol: 240 nmol/L

Urinary sulfonylurea screen was negative and brain imaging did not identify any structural cause for seizures.

Following the discontinuation of co-trimoxazole the patient's supplementary glucose requirements fell within 48 hours, regaining full glycaemic control. He was discharged after a full recovery to baseline functional status.

Outcome and follow-up

Once discharged, no further episodes of hypoglycaemia were reported and the patient was listed for routine outpatient follow-up with the nephrology team.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, there have been 21 published cases of hypoglycaemia in adults associated with the use of co-trimoxazole (including that reported here).3–20 Following a comprehensive literature review published in the 2006 Lancet, Strevel et al,15 a further seven cases have been identified. One of the recent report includes a case of hypoglycaemia in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome making our case the second observation of this adverse effect in this specific patient population (vasculitis).20

Renal impairment appears to be the strongest risk factor for hypoglycaemia due to co-trimoxazole use in the patient without diabetes, owing to the renal excretion of this drug.15 21 Of the 21 cases, 16 had proven renal impairment (namely chronic kidney disease; however, this adverse effect was also observed in cases with AKI in the context of normal baseline renal function).19 While our case does conform to this notion, it should be noted that we observed this adverse effect while our patient's serum creatinine was improving, and that the dose prescribed was adjusted for renal impairment.

Time to hypoglycaemia in our case was 4 days, with seizure activity noted at day 7. This is consistent with the literature; Strevel et al15 concluded that the median time to hypoglycaemia in the cases published before 2006 was 7 days, and in the further seven cases published since we calculate the median time to onset as 6 days. While our case might not present the most rapid onset hypoglycaemia, we believe that it is however one of the more severe and protracted cases reported. Our case is 1 of 10 cases that required >12 hours of intravenous glucose therapy (48 hours) and one of the few that required administration of glucagon—Forde et al.19 Just one other case, since the extensive review published in 2006, describes hypoglycaemia that persisted for 48 hours.17

The seizure complicating hypoglycaemia in our case is the sixth to be described.15 We were able to obtain adequate blood samples during this episode to allow further biochemical assessment. We demonstrate a raised C peptide and serum insulin level during an episode of symptomatic hypoglycaemia. In all cases, C peptide and serum insulin were measured, they were either noted to be elevated or inappropriately normal.15–20

It is hypothesised that the hypoglycaemia induced by co-trimoxazole is due to the sulfamethoxazole component's structural similarity with the sulfonylureas, hence causing hyperinsulinaemia secondary to β-cell stimulation.2 Interestingly, we present co-trimoxazole-induced hypoglycaemia despite a normal random cortisol and concomitant prescription of a corticosteroid (prednisolone), which in theory should be protective against this adverse effect owing to its promotion of insulin resistance.20 This phenomenon was also described by Senanayake et al,20 who also report a reduction in serum glucose parallel to a reduction in steroid dosage, further suggesting the sulfonylurea-like effect of co-trimoxazole.2

Our case, like the majority of others, required complete withdrawal of treatment to allow for restoration of normoglycaemia. A full recovery to normal glycaemic control was observed prior to discharge.

We believe that, although the reported incidence of severe hypoglycaemia secondary to co-trimoxazole appears to be low, the clinical significance of this adverse effect should be emphasised given that the administration of this agent in large doses is targeted to the very patient population at highest risk of hypoglycaemia. This is the second reported case of this adverse effect in a patient with vasculitis, and owing to the likely comorbid status and heavy immunosuppression this patient population receive—we believe that the significance of this case should be highlighted.

Learning points.

When prescribing co-trimoxazole in patients with renal impairment, consider whether dose adjustment to allow for renal dysfunction is required as these patients appear to be at highest risk of hypoglycaemia.15

The patients that are considered for co-trimoxazole therapy are usually those at the highest risk of this adverse effect, and therefore awareness is crucial and monitoring should be considered.2

Although the hypoglycaemia secondary to co-trimoxazole appears to be reversible, it can be profound and refractory in its initial stages posing a significant risk to life.

Footnotes

Contributors: TEC and AM were involved in design of work, and literature search and data collection. TEC was involved in drafting the article. AM and NN were involved in critical revisions of the article. AM was involved in final approval of the article to be submitted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Wang AT et al. Clinical review: drug-induced hypoglycemia: a systematic review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:741 10.1210/jc.2008-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson JK. Meyler's side effects of metabolic drugs. Elsevier, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arem R, Garber AJ, Field JB. Sulfonamide-induced hypoglycemia in chronic renal failure. Arch Intern Med 1983;143:827–9. 10.1001/archinte.1983.00350040217036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frankel MC, Leslie BR, Sax FL et al. Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole-related hypogylcemia in a patient with renal failure. N Y State J Med 1984;84:30–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portesky L, Moses AC. Hypoglycemia associated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole therapy. Diabetes Care 1984;7:508–9. 10.2337/diacare.7.5.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKnight JT, Gaskins SE, Pieroni RE et al. Severe hypoglycaemia associated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy. J Am Board Fam Pract 1988;1:143–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan DW, Oyston J. Sulphonylureas and hypoglycaemia. BMJ 1988;296:1328 10.1136/bmj.296.6632.1328-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schattner A, Rimon E, Green L et al. Hypoglycemia induced by co-trimoxazole in AIDS. BMJ 1988;297:742 10.1136/bmj.297.6650.742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansoor GA, Nicholson GD. Hypoglycaemia in chronic renal failure. West Indian Med J 1992;41:41–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JA, Kappel JE, Sharif MN. Hypoglycemia secondary to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole administration in a renal transplant patient. Ann Pharmacother 1993;27:304–6. 10.1177/106002809302700309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee AJ, Maddix DS. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-induced hypoglycemia in a patient with acute renal failure. Ann Pharmacother 1997;31: 727–32. 10.1177/106002809703100611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathews WA, Manint JE, Kleiss J. Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole-induced hypoglycemia as a cause of altered mental status in an elderly patient. J Am Board Fam Pract 2000;13:211–12. 10.3122/15572625-13-3-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes CA, Chik CL, Taylor GD. Co-trimoxazole-induced hypoglycemia in an HIV-infected patient. Can J Infect Dis 2001;12:314–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonc EN, Turul T, Yordam N et al. Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole induced prolonged hypoglycemia in an infant with MHC class II deficiency: diazoxide as a treatment option. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2003;16: 1307–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strevel EL, Kuper A, Gold WL. Severe and protracted hypoglycaemia associated with co-trimoxazole use. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:178–82. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70414-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosini JM, Martinez E, Jain R. Severe hypoglycemia associated with use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in a patient with chronic renal insufficiency. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:593–4. 10.1345/aph.1K558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunnari G, Celesia BM, Bellissimo F et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated severe hypoglycaemia: a sulfonylurea-like effect. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010;14:1015–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caro J, Navarro-Hidalgo I, Civera M et al. Severe, long-term hypoglycemia induced by co-trimoxazole in a patient with predisposing factors. Endocrinol Nutr 2012;59:146–8. 10.1016/j.endonu.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forde DG, Aberdein J, Tunbridge A et al. Hypoglycaemia associated with co-trimoxazole use in a 56-year-old Caucasian woman with renal impairment. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012:pii: bcr2012007215 10.1136/bcr-2012-007215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senanayake R, Mukhtar M. Cotrimoxazole-induced hypoglycaemia in a patient with Churg-Strauss syndrome. Case Rep Endocrinol 2013;2013:415810 10.1155/2013/415810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paap CM, Nahata MC. Clinical use of trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole during renal dysfunction. DICP 1989;23:646–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]