Abstract

Background

Biologically, hydrogen (H2) can be produced through dark fermentation and photofermentation. Dark fermentation is fast in rate and simple in reactor design, but H2 production yield is unsatisfactorily low as <4 mol H2/mol glucose. To address this challenge, simultaneous production of H2 and ethanol has been suggested. Co-production of ethanol and H2 requires enhanced formation of NAD(P)H during catabolism of glucose, which can be accomplished by diversion of glycolytic flux from the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas (EMP) pathway to the pentose-phosphate (PP) pathway in Escherichia coli. However, the disruption of pgi (phosphoglucose isomerase) for complete diversion of carbon flux to the PP pathway made E. coli unable to grow on glucose under anaerobic condition.

Results

Here, we demonstrate that, when glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Gnd), two major enzymes of the PP pathway, are homologously overexpressed, E. coli Δpgi can recover its anaerobic growth capability on glucose. Further, with additional deletions of ΔhycA, ΔhyaAB, ΔhybBC, ΔldhA, and ΔfrdAB, the recombinant Δpgi mutant could produce 1.69 mol H2 and 1.50 mol ethanol from 1 mol glucose. However, acetate was produced at 0.18 mol mol−1 glucose, indicating that some carbon is metabolized through the Entner–Doudoroff (ED) pathway. To further improve the flux via the PP pathway, heterologous zwf and gnd from Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Gluconobacter oxydans, respectively, which are less inhibited by NADPH, were overexpressed. The new recombinant produced more ethanol at 1.62 mol mol−1 glucose along with 1.74 mol H2 mol−1 glucose, which are close to the theoretically maximal yields, 1.67 mol mol−1 each for ethanol and H2. However, the attempt to delete the ED pathway in the Δpgi mutant to operate the PP pathway as the sole glycolytic route, was unsuccessful.

Conclusions

By deletion of pgi and overexpression of heterologous zwf and gnd in E. coli ΔhycA ΔhyaAB ΔhybBC ΔldhA ΔfrdAB, two important biofuels, ethanol and H2, could be successfully co-produced at high yields close to their theoretical maximums. The strains developed in this study should be applicable for the production of other biofuels and biochemicals, which requires supply of excessive reducing power under anaerobic conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13068-017-0768-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biohydrogen, Co-production of hydrogen and ethanol, Phosphoglucose isomerase deletion, Pentose-phosphate pathway, Escherichia coli

Background

Hydrogen (H2) is considered as a promising alternative to fossil fuel as it is an efficient energy carrier and produces zero carbon emission. Currently, H2 is produced by steam reforming process using natural gas, a non-renewable source. Therefore, as an alternative, biological H2 production by photolysis, photofermentation, or dark fermentation has been studied for decades due to its dependence on renewable energy source. Dark fermentation, owing to its rapidity and simplicity, usually is the preferred approach [1–3], though its theoretical H2 yield is low: typically <2 mol mol−1 glucose for mesophilic bacteria such as Escherichia coli [4] and <4 mol mol−1 glucose for strict anaerobes such as Clostridia, Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, Pyrococcus furiosus, and others [5–7]. To improve H2 production yield in E. coli, introduction of heterologous pathways such as ferredoxin- or NAD(P)H-dependent H2 production pathways has been attempted. The heterologous pathways, though functional in E. coli, have been shown to be highly inefficient and, as such, non-conducive to practical improvements in H2 yield [8]. In the case of strict anaerobes, higher yield, close to 4 mol mol−1 glucose, have been reported [9], albeit still not high enough to be commercially interesting. Due to the lack of a genetic tool box and/or the difficulty for gene manipulation, serious pathway engineering in strict anaerobes is yet to be attempted. As alternative means of addressing dark fermentation’s low H2 production yield, hybrid processes such as dark plus photofermentation, hythane process (production of H2 in the first stage and methane in the second), etc., have been studied [10–12]. Albeit efficient and feasible on the laboratory scale, these hybrid processes’ industrial application is highly challenging due to complicated reactor configurations and/or operation. We have suggested, as an alternative, a simple process by which H2 and ethanol are co-produced in a single bioreactor [13]. Ethanol in fact is a good liquid biofuel, and can easily be separated from gaseous H2. Co-production of ethanol with H2, moreover, can significantly increase the energy recovery of dark fermentation and, thereby, make H2 production from glucose more attractive [14].

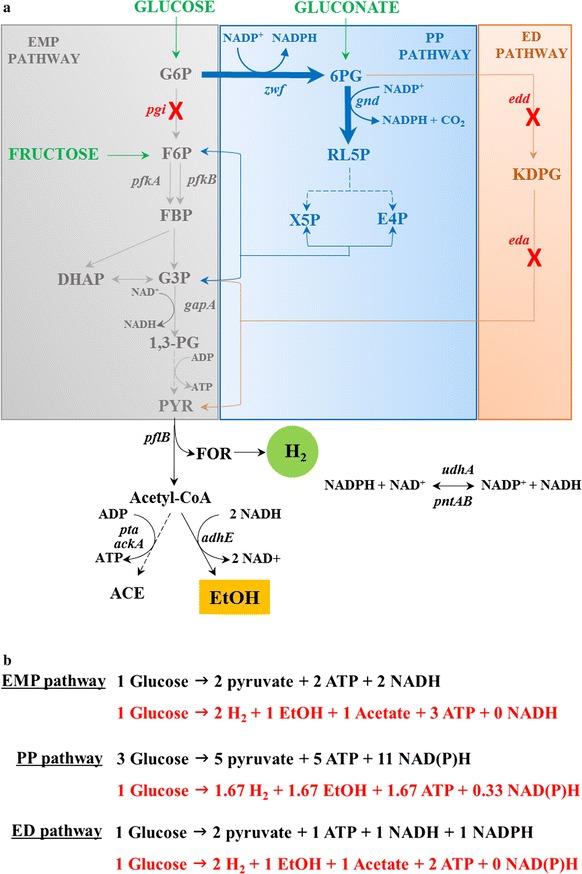

Under typical anaerobic conditions, E. coli metabolizes most of the glucose through the EMP pathway, producing H2 at 2 mol mol−1 glucose along with ethanol and acetate each at 1 mol mol−1 glucose (Fig. 1). Co-production of ethanol with H2 requires the production of ethanol instead of acetate, which entails conversion of the two molecules of acetyl-CoA produced from one molecule of glucose to two molecules of ethanol, without producing acetate. This requires additional NAD(P)H generation during glycolysis. For this purpose, use of a more reduced carbon source than glucose, such as glycerol, has been studied [15] for the production of equimolar H2 and ethanol without acetate. However, with glucose as the carbon source, the theoretical maximum yield of ethanol cannot exceed 1 mol per mol of glucose, because the EMP pathway generates only 2 mol NADH per mol of glucose. However, if glucose is exclusively metabolized through the PP pathway, 3.67 mol NAD(P)H per mol of glucose can be generated, which, in theory, enables co-production of ethanol and H2, each at 1.67 mol mol−1, without acetate [13]. To this end, blockage of the EMP pathway by deletion of phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi) has been attempted; unfortunately though, the Δpgi strain could not grow anaerobically. In response, for co-production of H2 and ethanol, alternative, phosphofructokinase-1 (PfkA) deletion mutants have been developed and studied (Fig. 1) [14, 16]. The ΔpfkA strains could grow well after long adaptation to anaerobic conditions [14] and produced significant amounts of H2 and ethanol (~1.8 mol H2 mol−1 and ~1.40 mol ethanol mol−1) when Zwf and Gnd, the key enzymes of the PP pathway, were overexpressed. However, due to the active expression of pfkB, which encodes for isozyme of PfkA, up to 30% of the glucose was metabolized through the EMP pathway in the ΔpfkA strains, thus resulting in substantial acetate production (~0.15 mol mol−1) [14].

Fig. 1.

a Pathway engineering for promotion of carbon flux through PP pathway. The EMP and ED pathways were disrupted by deleting pgi, edd, and eda (red crosses), and the PP pathway was activated by the overexpression of zwf and gnd (bold blue arrows). b Theoretical carbon and energy balance of EMP, PP (non-cyclic), and ED pathway of base strain (SH5) for co-production of H2 and ethanol. Genes: pgi—phosphoglucose isomerase, pfk—phosphofructokinase, gapA—glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, pta—phosphotransacetylase, ackA—acetate kinase, adhE—alcohol dehydrogenase, zwf—glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, gnd—6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, edd—Entner–Doudoroff dehydratase, eda—Entner–Doudoroff aldolase, udhA—soluble transhydrogenase, pntAB—membrane-bound transhydrogenase. Metabolites: G6P—Glucose-6-phosphate, F6P—fructose-6-phosphate, FBP—fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, DHAP—dihydroxyacetone phosphate, G3P—glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, 1,3-PG—1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, PYR—pyruvate, FOR—formate, H2—hydrogen, AcCoA—acetyl-CoA, ACE—acetate, EtOH—ethanol, 6PG—6-phosphogluconate, RL5P—ribulose-5-phosphate, X5P—xylose-5-phosphate, E4P—erythrose-4-phosphate, KDPG—2-Keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate

In the present study, we determined that Δpgi mutants can grow anaerobically when Zwf and Gnd are overexpressed. Consequently, we investigated complete blockage of the carbon flux through the EMP pathway and the concomitantly improved co-production of H2 and ethanol. Also, to address the two major disadvantages of Zwf and Gnd of E. coli—their dependence on NADP+ as the cofactor and serious inhibition of their activities by NADPH at the enzyme level—expressions of heterologous Zwf and Gnd from other microorganisms have been studied. We also attempted deletion of the ED pathway for operation of the PP pathway as the sole glycolytic route. Our results demonstrate that Δpgi mutants can grow under anaerobic conditions and co-produce H2 and ethanol at near-theoretical yields. Additionally, the data obtained show that the developed strains can be used as an interesting platform when generation of considerable reducing power is needed in anaerobic glucose metabolism [17, 18].

Methods

Strains, plasmids, and materials

The Escherichia coli BW25113 mutant strain (SH5) from our previous study [19] was used as a base strain in this work. Restriction and DNA-modifying enzymes were obtained from New England Bio-Labs (Beverly, MA, USA). The Miniprep and DNA gel extraction kits were purchased from Qiagen (Mannheim, Germany). The primers were synthesized by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea). The yeast extract (Cat. 212750) and Bacto™ tryptone (Cat. 211705) were acquired from Difco (Becton–Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Unless indicated otherwise, all of the other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Construction of recombinant E. coli strains

For overexpression of Zwf and/or Gnd, the plasmids pEcZ, pEcG, and pEcZG from our previous study were utilized [14]. Gene deletion was performed using either the λ-Red recombinase (deletion of pgi) or pKOV system (deletion of edd, udhA, and pntAB) [20, 21]. Briefly, for deletion using λ-Red recombinase, hybrid complementary primers for pgi of E. coli BW25113 and the antibiotic cassette (FRT-kan-FRT) in pKD4, were used. The amplified FRT-kan-FRT cassette was inserted to SH5 harboring pKD46 plasmid by electroporation. The resulting kanamycin-resistant E. coli SH5 containing FRT-kan-FRT in the pgi region was isolated using antibiotic resistance screening and PCR with the locus-specific primers. For deletion using pKOV system, recombinant pKOV plasmid was made with PCR-amplified upstream and downstream 500 bp of the target gene. This recombinant plasmid was used to perform double recombination and remove the target gene using sucrose (sacB-dependent) as selection pressure. The heterologous zwf and gnd were codon optimized and synthesized by GenScript (NJ, USA) (Additional file 1: Table S1). All the genes for overexpression were cloned in pDK7 vector and overexpressed under the control of the tac promoter [22]. The list of strains constructed in this study is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Description | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| SH5 | BW25113 ΔhycA ΔhyaAB ΔhybBC ΔldhA ΔfrdAB | Kim et al. [19] |

| SH5Δpgi | SH5Δpgi | This study |

| SH5Δpgi_Z | SH5Δpgi harboring pEcZ | |

| SH5Δpgi_ZG | SH5Δpgi harboring pEcZG | |

| SH5Δpgi_ZGU | SH5Δpgi harboring pEcZGU | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z L G E | SH5Δpgi harboring pLmZ-EcG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z Z G E | SH5Δpgi harboring pZmZ-EcG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z E G C | SH5Δpgi harboring pEcZ-CgG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z L G C | SH5Δpgi harboring pLmZ-CgG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z Z G C | SH5Δpgi harboring pZmZ-CgG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z E G G | SH5Δpgi harboring pEcZ-GoG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z L G G | SH5Δpgi harboring pLmZ-GoG | |

| SH5Δpgi_Z Z G G | SH5Δpgi harboring pZmZ-GoG | |

| SH5ΔpgiΔedd | SH5Δpgi Δeddeda | |

| SH5ΔpgiΔedd_G | SH5ΔpgiΔedd harboring pEcG | |

| SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG | SH5ΔpgiΔedd harboring pEcZG | |

| SH5ΔpgiΔedd_Z L G G | SH5ΔpgiΔedd harboring pLmZ-GoG | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDK7 | Expression vector | Kleiner et al. [22] |

| pEcZ | pDK7 carrying zwf of E. coli BW25113 | Sundara Sekar et al. [14] |

| pEcZG | pDK7 carrying zwf, gnd of E. coli BW25113 | |

| pEcZGU | pDK7 carrying zwf, gnd, udhA of E. coli BW25113 | This study |

| pLmZ-EcG | pDK7 carrying zwf of L. mesenteroides and gnd of E. coli BW25113 | |

| pZmZ-EcG | pDK7 carrying zwf of Z. mobilis and gnd of E. coli BW25113 | |

| pEcZ-CgG | pDK7 carrying zwf of E. coli BW25113 and gnd of C. glutamicum | |

| pLmZ-CgG | pDK7 carrying zwf of L. mesenteroides and gnd of C. glutamicum | |

| pZmZ-CgG | pDK7 carrying zwf of Z. mobilis and gnd of C. glutamicum | |

| pEcZ-GoG | pDK7 carrying zwf of E. coli BW25113 and gnd of G. oxydans | |

| pLmZ-GoG | pDK7 carrying zwf of L. mesenteroides and gnd of G. oxydans | |

| pZmZ-GoG | pDK7 carrying zwf of Z. mobilis and gnd of G. oxydans | |

Culture conditions

Luria-Bertani broth was used to culture the cells for genetic engineering and culture maintenance work. Production studies were performed in modified M9 medium containing 5.0 g L−1 glucose or gluconate, 1.0 g L−1 yeast extract, 3.0 g L−1 Na2HPO4, 1.5 g L−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g L−1 NH4Cl, 0.25 g L−1 NaCl, 0.25 g L−1 MgSO4, and 0.01 g L−1 CaCl2. Kanamycin (50 µg mL−1) and chloramphenicol (25 µg mL−1) were added to the medium for culturing of the recombinant strains. The medium was also supplemented with 0.2 mg L−1 NiSO4, 1.4 mg L−1 FeSO4, 0.2 mg L−1 Na2SeO3, 0.2 mg L−1 Na2MoO4, and 8.8 mg L−1 cysteine HCl for supporting the synthesis of co-production-related enzymes. The cells were cultured anaerobically with 50 mL of M9 medium in 165 mL serum bottles. The serum bottles with the media were flushed with argon for 15 min to create the anoxic condition for fermentation. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in an orbital shaker rotating at 200 rpm. The expressions of Zwf and Gnd were induced by the addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), unless stated otherwise.

Total RNA isolation and real-time PCR

The recombinant strains were induced with IPTG and harvested during the late exponential growth phase. RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen Inc., USA) was added to the cell pellets, which were stored at −80 °C to prevent RNA degradation. Total RNA was extracted using the Nucleospin® RNA isolation kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) and converted to cDNA using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, USA). The RT-PCR primers were designed using Primer Express® software. RT-PCR analysis was performed using the StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The experiment was conducted in duplicate using the SYBR Green method, and the relative mRNA was quantified by the ΔCT method [23]. rpoD was utilized as the endogenous control.

Determination of enzyme activities

The enzyme activities of Gnd and Zwf were measured as described in Moritz et al. [24], with slight modifications. Briefly, the enzyme activities were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.2 mM NADP+, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM glucose-6-phosphate or 6-phosphogluconate. The reduction of NADP+ was observed at 340 nm. The extinction coefficient (ε 340) of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1 was used for calculating the amount of NADPH formed in the assay. All measurements were performed at 30 °C.

Analytical methods

Cell growth was monitored by UV spectrophotometry (Lambda 20, Perkin Elmer, USA) measurement of the optical density (OD600) at 600 nm. Gases such as H2 and CO2 were measured by gas chromatography (DS6200 Donam Systems Inc., Seoul, Korea) equipped with a TCD detector. The stainless steel column of gas chromatography was packed with either Hayesep Q (for CO2 analysis, Alltech Deerfield, IL, USA) or Molecular Sieve 5A (for H2 analysis, Alltech Deerfield, IL, USA). Argon was used as the carrier gas and its flow rate was set at 30 mL min−1. The temperature of injector, column oven, and TCD detector was maintained at 90, 80, and 120 °C, respectively, during analysis. Glucose, ethanol, and all of the other metabolites were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent Technologies, HP, 1200 series) equipped with a refractive index (RID) and photodiode array (DAD) detectors. The post-fermentation medium was centrifuged and filtered, and samples were eluted through a 300 mm × 7.8 mm Aminex HPX-87H (Bio-Rad) column at 65 °C using 2.5 mM H2SO4. The protein concentrations of the samples used in the enzyme activities were determined by the Bradford method as described previously [25] using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Results and discussion

Growth of E. coli mutant lacking pgi under aerobic and anaerobic conditions

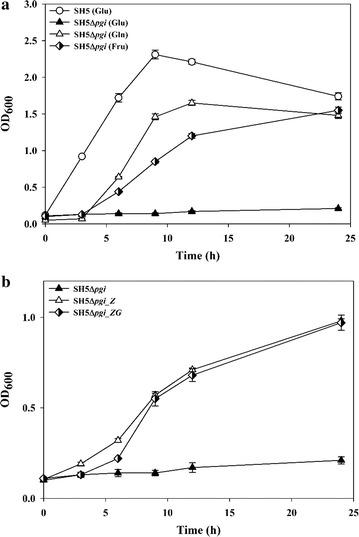

To completely block the carbon flux through the EMP pathway and divert it through the PP pathway, the pgi gene was deleted from the E. coli BW25113 mutant strain (designated as ‘SH5’), which has several deletions in such enzymes as uptake hydrogenases (hyaAB, hybBC), the negative regulator of formate-hydrogen lyase (hycA), lactate dehydrogenase (ldhA), and fumarate reductase (frdAB) [19]. The resulting mutant strain E. coli SH5Δpgi could grow well on glucose under aerobic conditions but not under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 2a). Laboratory adaptive evolution by repeated transfers in glucose medium under anaerobic condition was not successful (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). With fructose or gluconate as the carbon source, however, SH5Δpgi could grow well under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Fructose enters the EMP pathway through the fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) node, and gluconate enters the PP/ED pathways through the 6-phosphogluconate (6PG) node (Fig. 1). The growth capability of SH5Δpgi on either fructose or gluconate indicated that both the EMP pathway (after F6P) and the PP/ED pathway (after 6PG) functioned properly. In this light, we hypothesized that the lack of anaerobic growth of SH5Δpgi on glucose was caused by its inability to convert glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) to 6PG. We further posited that, when expressed from the chromosome, the activities of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) and/or 6-phosphogluconolactonase (Pgl), which are the enzymes directing G6P towards the PP or ED pathway, are very low [26].

Fig. 2.

Anaerobic growth of SH5, SH5Δpgi, and recombinant SH5Δpgi strains. a Growth of SH5 and SH5Δpgi on different carbon sources such as glucose (Glu), gluconate (Gln), and fructose (Fru). b Growth of SH5Δpgi, SH5Δpgi_Z, and SH5Δpgi_ZG with glucose as carbon source. Refer to Table 1 for the genotype of each strain

To confirm our hypothesis, zwf was homologously overexpressed by a multi-copy plasmid under the IPTG-inducible tac promoter. The resultant recombinant, SH5Δpgi_Z could grow well on glucose under anaerobic conditions, though rather slowly compared with its parental strain SH5 (Fig. 2b). In order to determine if gnd expression can further improve cell growth, SH5Δpgi_ZG was developed and tested. No difference from SH5Δpgi_Z was observed. It was concluded that the incapacity of E. coli Δpgi for anaerobic growth is rooted in the inefficient conversion of G6P to 6PG.

Co-production of H2 and ethanol by E. coli Δpgi

Co-production of H2 and ethanol was studied and compared among the strains of SH5, SH5Δpgi_Z, and SH5Δpgi_ZG (Table 2). The strains were induced with 0.1 mM IPTG, and the metabolites were analyzed at ~24 h of cultivation, when co-production was highest. SH5Δpgi_Z, as compared with SH5, showed improved production of all three major metabolites (H2, ethanol, and acetate); this was attributed to the lower cell growth of SH5Δpgi_Z (see Fig. 2) and the conversion of more glucose carbon to those metabolites. However, contrary to our expectation, the ratio of the production yield of ethanol to acetate did not increase in SH5Δpgi_Z relative to SH5 (Table 2). In fact, if the PP pathway, which generates more NAD(P)H, functions as the major glycolytic pathway in SH5Δpgi_Z, more ethanol and less acetate should be produced. It was expected that the ED pathway, rather than the PP pathway, was activated by the overexpression of zwf, which generates the same amount of NAD(P)H as the EMP pathway [13]. In comparison, when both zwf and gnd were overexpressed (SH5Δpgi_ZG), ethanol production was greatly improved to 1.44 mol mol−1 with a concomitant acetate reduction to 0.22 mol mol−1. We concluded that whereas the cell growth of the Δpgi mutant can be recovered by the overexpression of zwf alone, the activation of the PP pathway requires overexpression of both zwf and gnd. Subsequent experiments with gluconate as a carbon source re-confirmed the importance of gnd overexpression for activation of the PP pathway (Table 2). Ethanol production from gluconate by SH5Δpgi_Z was 0.68 mol mol−1, similar to that by SH5, while that by SH5Δpgi_ZG was 0.92 mol mol−1.

Table 2.

Co-production by recombinant SH5Δpgi strains overexpressing Zwf and Gnd

| Substrate | Strains | Yields of metabolites (mol mol−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Ethanol | Acetate | ||

| Glucose | SH5 | 1.44 ± 0.07 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 0.67 ± 0.04 |

| SH5Δpgi_Z | 1.81 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | |

| SH5Δpgi_ZG | 1.68 ± 0.06 | 1.44 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | |

| Gluconate | SH5 | 1.72 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 1.31 ± 0.03 |

| SH5Δpgi_Z | 1.70 ± 0.05 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | |

| SH5Δpgi_ZG | 1.69 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.85 ± 0.02 | |

Yields of metabolites were calculated from three individual experiments

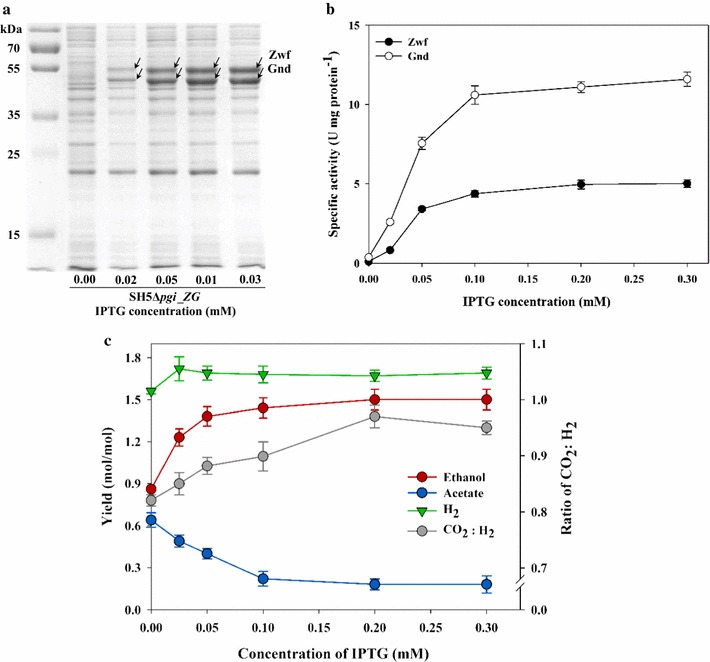

Although expression of zwf and gnd greatly improved ethanol production while reducing acetate production, the theoretical maximum yield of ethanol production (1.67 mol mol−1 glucose) was not achieved. To determine if ethanol production could be further improved, the expression levels of the two major enzymes, Zwf and Gnd, were varied by varying the IPTG concentration within the 0–0.3 mM range during the cultivation of SH5Δpgi_ZG (Fig. 3). With increasing IPTG concentration, production of Zwf and Gnd proteins (as analyzed by SDS-PAGE) and their enzymatic activities (from crude cell extract) increased almost linearly to 0.3 mM IPTG. Accordingly, while acetate production decreased, ethanol production and the CO2/H2 ratio gradually increased. This indicated that when Gnd activity is enhanced, the flux through the PP pathway becomes more prominent than the ED pathway [16]. However, the ethanol yield increase, or the decrease in acetate production, almost halted at ~0.1 mM IPTG; moreover, even at the highest IPTG concentration tested in this study, 0.3 mM, about 0.2 mol acetate mol−1 glucose was produced. This observation suggests that achieving the theoretical maximum ethanol production level is impossible by simply controlling the expression level of the current Zwf and Gnd, because the carbon flux through the PP pathway cannot be sufficiently enhanced. Here, it seems that either the enzyme kinetics or the competition between Gnd and Edd determines the carbon distribution at the 6PG node, the amount of NAD(P)H production, and/or the ethanol production yield. In any case, we could achieve high co-production yields, 1.69 mol H2 mol−1 glucose, and 1.50 mol ethanol mol−1 glucose, with SH5Δpgi_ZG at 0.2 mM IPTG.

Fig. 3.

Effect of inducer concentration on co-production of H2 and ethanol by SH5Δpgi_ZG. a SDS-PAGE analysis of Zwf (55 kDa) and Gnd (51 kDa) in soluble fraction. b Enzyme activity of Zwf and Gnd of SH5Δpgi_ZG induced with different IPTG concentrations. c Metabolite yields and ratios of CO2 to H2 evolution of SH5Δpgi_ZG induced with 0, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 mM IPTG

Next, RT-PCR analysis was performed to examine the changes in the gene expressions of the major glycolytic enzymes in SH5Δpgi_Z and SH5Δpgi_ZG (Table 3; Additional file 2: Appendix A). In both strains, transcription of pgi was not observed, confirming the removal of pgi. The zwf and/or gnd genes were highly expressed in SH5 Δpgi_Z and/or Δpgi_ZG, and their levels increased when the cells were induced with higher IPTG concentrations. We noticed that the expressions of pfkA and gapA increased as Zwf and Gnd were more expressed. We attributed these increased transcriptions to enhanced PP pathway flux, because the PP pathway is linked with the EMP pathway at F6P (pfkA) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P; gapA) nodes, and, with the ED pathway at G3P and pyruvate nodes [27]. Interestingly, transcription of adhE also significantly increased when the PP pathway was activated. In this regard, it has been reported that adhE transcription increases when the intracellular NAD(P)H level increases, and that this can enhance ethanol production [28]. Surprisingly in the present results, the expression level of udhA, encoding NADH:NADPH transhydrogenase that converts NADPH to NADH, did not change upon activation of the PP pathway. This raises the important question of whether NADPH is used directly or after being converted to NADH in the production of ethanol from acetyl-CoA (see “Limitations on PP pathway operation under anaerobic condition and expression of transhydrogenase”).

Table 3.

Relative transcription levels of key glycolytic enzymes in SH5Δpgi_Z and SH5Δpgi_ZG

| Gene | SH5Δpgi_Z (0.1 mM) | SH5Δpgi_ZG (0.1 mM) | SH5Δpgi_ZG (0.2 mM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pgi | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| zwf | 2090.91 ± 146.36 | 2693.55 ± 212.52 | 8001.77 ± 400.09 |

| gnd | 6.03 ± 0.21 | 2155.47 ± 73.18 | 6039.95 ± 259.79 |

| pfkA | 2.16 ± 0.11 | 3.59 ± 0.06 | 5.48 ± 0.13 |

| pfkB | 2.59 ± 0.13 | 1.29 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.03 |

| gapA | 34.12 ± 1.54 | 44.01 ± 0.96 | 80.95 ± 3.24 |

| edd | 1.41 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 |

| tktA | 12.20 ± 0.24 | 5.72 ± 0.12 | 7.28 ± 0.16 |

| pflB | 42.99 ± 1.38 | 21.51 ± 0.65 | 37.04 ± 0.74 |

| fhlA | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 |

| udhA | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.01 |

| adhE | 4.51 ± 0.05 | 7.22 ± 0.12 | 13.76 ± 0.47 |

The result was from three individual experiment repeats

rpoD was used as the endogenous control and the transcriptional level of rpoD was considered as 1

Construction and characterization of SH5ΔpgiΔedd, the strain using PP pathway as sole glycolytic route

The improved activity of Zwf and Gnd could not completely eliminate acetate production in SH5Δpgi_ZG. Therefore, to make the PP pathway the sole glycolytic route, the ED pathway was blocked by disruption of the edd and eda genes from SH5Δpgi. The resultant SH5 ΔpgiΔedd strain could grow on glucose under aerobic conditions but not at all under anaerobic conditions, even after overexpression of Zwf and Gnd (see Additional file 1: Fig. S2). This result, albeit disappointing, confirmed that the ED pathway is functioning in the SH5Δpgi_ZG strain and metabolizing a portion of the glucose.

The inability of SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG to grow on glucose under anaerobic condition is attributed to redox imbalance. According to the carbon and energy balance, when one glucose is fully metabolized through the PP pathway, 0.33 NADPH is generated along with 1.67 H2 and 1.67 ethanol [13] (Fig. 1b). The supplementation of yeast extract in the medium could have worsen the redox imbalance because it contains complex amino acids and some carbohydrates which can contribute to the regeneration of NAD(P)H. If excess NADPH is accumulated, the PP pathway will be blocked along with termination of cell growth. To prove this hypothesis, two experiments were carried out. First, SH5ΔpgiΔedd _ZG was grown on gluconate as the gluconate is more oxidized than glucose, and so no excess NADPH is accumulated. As expected, SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG could grow on gluconate, though the rate is very slow (see Additional file 1: Fig. S2). In the course of that growth, ethanol and acetate were produced at yields of 0.79 and 0.84 mol mol−1, respectively, which makes the gluconate metabolism redox-balanced. In the second experiment, SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG was grown on glucose but in the presence of nitrate (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Nitrate can be used as an external electron acceptor and regenerate NAD(P)+ under anaerobic conditions [29]. The results showed that the addition of nitrate recovered the growth of SH5ΔpgiΔedd even without the expression of Zwf and Gnd (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). The overexpression of Zwf and Gnd in the presence of nitrate increased the glucose consumption. However, neither H2 nor ethanol was produced; instead, acetate was the sole metabolite. In the presence of nitrate, E. coli oxidizes NAD(P)H to reduce nitrate and produce ATP. In summary, these two experiments strongly suggest that the redox imbalance and/or excessive NADPH generated by the PP pathway prevented SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG growth on glucose under anaerobic conditions.

It is possible to determine the minimal glucose flux to the ED pathway allowing for redox-balanced glucose metabolism using the carbon balance equation of PP and ED pathway (Fig. 1b) (see Additional file 1: Fig. S4). When NAD(P)H used for cell growth is ignored, the estimated minimal flux ratio of the ED pathway (i.e., ED flux/sum of PP and ED fluxes) is 0.14. If the minimal flux ratio of the ED pathway is below 0.14, the production and consumption of NAD(P)H cannot be matched by the production of ethanol and acetate. On the other hand, at any flux ratios above 0.14, combined production of acetate and ethanol makes the glucose metabolism redox-balanced and allows cells to grow.

Limitations on PP pathway operation under anaerobic condition and expression of transhydrogenase

According to the redox-balance analysis results plotted in Additional file 1: Fig. S4, the current SH5Δpgi_ZG had a higher ED flux (~0.32) than the ideal case (0.14). We speculate that despite high expression by the multi-copy plasmid, the enzymatic activities of Zwf and Gnd were low under the physiological conditions, and that this might be the reason why the flux ratio to the PP pathway did not increase above the 0.1 mM IPTG shown in Fig. 3. It is known that Zwf and Gnd of E. coli are almost exclusively NADP+ dependent and that their enzymatic activities are highly inhibited by NADPH [24, 30] (see Additional file 1: Table S2). Because the roles of Zwf and Gnd are so important, we cloned and characterized these enzymes from our own host E. coli BW25113 (Additional file 1: Fig. S5, Additional file 1: Table S2). The enzymes were expressed with a C-terminal His-tag and characterized after purification by Ni–NTA chromatography. Both of them were shown to be strictly dependent on NADP+, and no activity was observed with NAD+ as the cofactor. The specific activities and K m values of the purified Zwf and Gnd were similar to those that have been reported [30] (Additional file 1: Table S2). Additionally, we found that the two enzymes were inhibited by NADPH at similar levels (K i = ~ 40 μM) but not at all by NADH.

The problem associated with high intracellular NADPH concentration and consequent inhibition on Zwf and Gnd can be solved in two ways: by (1) reducing the NADPH concentration and/or (2) employing less NADPH-sensitive enzymes. To explore the first approach, we overexpressed UdhA, the soluble transhydrogenase for the conversion of NADPH to NADH. E. coli strains have two transhydrogenases, one soluble (udhA) and the other membrane bound (pntAB) [31]. Although both enzymes work reversibly, the former mainly catalyzes the reaction for the conversion of NADPH to NADH, and the latter, the reverse reaction [31]. To our disappointment, even after the overexpression of UdhA under a strong tac promoter, no improvement in ethanol production was observed in SH5Δpgi_ZG (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). Further, deletion of both udhA and pntA from SH5Δpgi_ZG did not affect cell growth or metabolite formation: SH5ΔpgiΔudhAΔpntA_ZG grew similar to SH5Δpgi_ZG and produced similar amounts of H2, ethanol, and acetate (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). These results are puzzling, because they indicate that the roles of the two transhydrogenases are negligible in glucose metabolism, and also that ethanol production in SH5Δpgi_ZG and other derived strains might be NADPH dependent. In any case, it is clear that overexpression of transhydrogenases cannot be the solution to the problem that necessitates reduction of intracellular NADPH levels and/or enhancement of carbon flux through the PP pathway.

Use of heterologous zwf and gnd

In another attempt to improve the carbon flux to the PP pathway, we overexpressed heterologous Zwf and Gnd which are less inhibited by NADPH. If such enzymes can use NAD+ as the cofactor, the reduction of the intracellular NADPH level would be also expected. For the Zwf and Gnd reported in the literature and enzyme databases, cofactor specificity, activity, and NADPH-dependent inhibition were analyzed and compared (Additional file 1: Table S2). The Zwf from Zymomonas mobilis (ZZ) had an approximately sevenfold higher activity than that of E. coli (ZE; note that the subscript ‘E’ was added to avoid confusion) [32]. Furthermore, it could use both NAD+ (K m, 210 µM) and NADP+ (K m, 40 µM), though preferring the latter more. The Zwf from Leuconostoc mesenteroides (ZL) also showed a sevenfold higher activity than that of ZE, and could use NAD+ as a cofactor, having a higher affinity (K m, 106 µM) than ZZ [33, 34]. Interestingly, the Gnd from Gluconobacter oxydans (GG) showed a higher affinity to NAD+ (K m, 64 µM) than to NADP+ (K m, 440 µM), whereas Gnd from Corynebacterium glutamicum (GC) showed a fivefold higher activity than that of E. coli (GE), though its use of NAD+ as a cofactor is not known [24, 35].

Next, different recombinant plasmids were constructed for the expression of heterologous Zwf (ZE, ZL, ZZ) and Gnd (GE, GG, GC) in various combinations and then introduced to SH5Δpgi to generate eight recombinant strains (Table 4). These recombinant SH5Δpgi strains were studied for the growth and production of H2 and ethanol with glucose as the carbon source. Except for SH5Δpgi_Z E G C and SH5Δpgi_Z E G G, the other (six) strains grew well and produced H2 similar to that of SH5Δpgi_Z E G E at 1.6 ± 0.1 mol mol−1 glucose. Those six recombinant strains also generated similar or higher amounts of ethanol than SH5Δpgi_ZG; among them, the SH5Δpgi_Z L G G strain, which expresses Zwf of L. mesenteroides and Gnd of G. oxydans, showed the highest ethanol production yield at 1.62 mol mol−1 glucose as well as the lowest acetate production yield at ~0.06 mol mol−1 glucose. It was considered that the high activity and dual-cofactor specificity of ZL along with the NAD+ dependence of GG were the main reasons for the improved performance of SH5Δpgi_Z L G G. The flux ratio of the ED pathway in this strain, moreover, was estimated to be close to the thermodynamically allowed lowest level, 0.14 (see Additional file 1: Fig. S4).

Table 4.

Co-production by recombinant SH5Δpgi and SH5ΔpgiΔedd strains overexpressing heterologous Zwf and Gnd

| Strains | Relative growth rate | Yield of metabolites (mol mol−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Acetate | ||

| Δpgi_ZG | +++ | 1.44 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.03 |

| Δpgi_ZLGE | ++ | 1.48 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| Δpgi_ZZGE | +++ | 1.49 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.01 |

| Δpgi_ZEGC | + | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| Δpgi_ZLGC | +++ | 1.46 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.01 |

| Δpgi_ZZGC | +++ | 1.32 ± 0.07 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

| Δpgi_ZEGG | + | 1.52 ± 0.09 | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| Δpgi_ZLGG | ++ | 1.62 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| Δpgi_ZZGG | ++ | 1.46 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| ΔpgiΔedd_ZLGaG | ++ | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.01 |

The result was from three individual experiment repeats

aΔpgiΔedd_ZLGG was grown on gluconate

The same plasmid expressing both Zwf of L. mesenteroides and Gnd of G. oxydans (pLmZ-GoG) was introduced to SH5ΔpgiΔedd to determine if these highly efficient Zwf and Gnd can enable its anaerobic growth. As expected, the resulting recombinant SH5ΔpgiΔedd_Z L G G could not grow anaerobically with glucose as the carbon source. This confirmed that redox imbalance does not permit use of the PP pathway as the sole glycolytic route of glucose metabolism under anaerobic conditions. The same SH5ΔpgiΔedd_Z L G G strain was also cultured on gluconate as the carbon source. In fact, it could grow much better than SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG (Additional file 1: Fig. S2), producing more ethanol (1.01 vs. 0.79 mol mol−1) and less acetate (0.40 vs. 0.85 mol mol−1). This result confirmed once again that the highly efficient Zwf (ZL) and Gnd (GG) can effectively activate the PP pathway.

The ΔpfkA strains could grow well after long adaptation to anaerobic growth [14] and produced good amounts of H2 and ethanol (~1.7 mol H2 mol−1 and ~1.40 mol ethanol mol−1) when Zwf and Gnd, the key enzymes of the PP pathway, were overexpressed. However, due to the active expression of pfkB which encodes for the isozyme of PfkA, up to 30% of glucose was metabolized through the EMP pathway in the ΔpfkA strains and substantial amount of acetate was produced (~0.15 mol mol−1). On the other hand, the Δpgi strains led us to understand the metabolic hurdles in achieving theoretical maximum yield. In addition, the usage of efficient Zwf and Gnd enzymes in the Δpgi strains led us to successfully achieve the theoretical maximum yield of H2 and ethanol (~1.6 mol mol−1 each).

Conclusions

The E. coliΔpgi mutant could grow on glucose under anaerobic conditions when Zwf was overexpressed, but when both Zwf and Gnd were overexpressed, diversion of the carbon flux through the PP pathway and efficient co-production of H2 and ethanol were possible. Operation of the PP pathway as the sole glycolytic route for glucose under anaerobic conditions, however, was not possible, due to the redox imbalance. When the EMP pathway was blocked by pgi deletion, there existed, for the ED pathway, a critical flux ratio (0.14) above which cell growth was possible. The flux distribution between the PP and ED pathways at the 6-phosphogluconate node, and the co-production yield of H2 and ethanol, were determined by the characteristics of Zwf and Gnd. When zwf from L. mesenteroides and gnd from G. oxydans, both of which use NAD+ and NADP+ as cofactors and are less inhibited by NADPH, were employed, the best co-production yield of H2 and ethanol (1.74 mol H2 mol−1 glucose; 1.62 mol ethanol mol−1 glucose), close to the theoretical maximum values (1.67 mol mol−1 glucose for each), resulted. Activation of the PP pathway, as presented in this work, will be found to be useful for developing efficient biocatalysts for other biofuels and biochemicals that require additional reducing power and need to be produced under anaerobic conditions.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Details of Zwf and Gnd used in this study. Table S2. Kinetic properties of Zwf and Gnd used in this study. Figure S1. Adaptive evolution for anaerobic growth of SH5Δpgi with glucose as substrate. Figure S2. Anaerobic growth of recombinant SH5ΔpgiΔedd strains on glucose (Glu) and gluconate (Gln). Refer to Table 1 for the genotype of each strain. Figure S3. Growth and acetate production yield of SH5ΔpgiΔedd and SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG on glucose in the presence of nitrate. Figure S4. Theoretical prediction of relation between dependence on ED pathway and ethanol and acetate production. Redox-imbalanced region denotes the production of excess NADPH than pyruvate. Figure S5. SDS-PAGE analyses of Zwf (55 kDa) and Gnd (51 kDa) in soluble fraction SH5_pDK7_zwf (Lane 1) and SH5_pDK7_gnd (Lane 2) and purified Zwf (Lane 3) and Gnd (Lane 4) by Ni–NTA chromatography. Figure S6. Growth and metabolites production yield of SH5Δpgi_ZGU and SH5ΔpgiΔudhAΔpntA_ZG on glucose.

Additional file 2: Appendix A. Raw data of RT-PCR analysis.

Authors’ contributions

BSS, ES, and SP designed the research. BSS and ES performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. The manuscript was revised and critical comments were provided by SP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was supported by C1 Gas Refinery Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2016M3D3A1A01913248). This work was also supported by the Advanced Biomass R&D Center (ABC) of Global Frontier Project funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (ABC-2011-0031361). The authors are grateful also to the BK21 Plus program at Pusan National University.

Abbreviations

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- ED

Entner–Doudoroff

- EMP

Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas

- H2

hydrogen

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside

- OD600

optical density

- Pgi

phosphoglucose isomerase

- PP

pentose-phosphate

Contributor Information

Balaji Sundara Sekar, Email: biobalaji.s@gmail.com.

Eunhee Seol, Email: seh16@pusan.ac.kr.

Sunghoon Park, Email: parksh@pusan.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Rittmann S, Herwig C. A comprehensive and quantitative review of dark fermentative biohydrogen production. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:115–133. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallenbeck PC. Fermentative hydrogen production: principles, progress, and prognosis. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34:7379–7389. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.12.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abo-Hashesh M, Wang R, Hallenbeck PC. Metabolic engineering in dark fermentative hydrogen production; theory and practice. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:8414–8422. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh YK, Raj SM, Jung GY, Park S. Current status of the metabolic engineering of microorganisms for biohydrogen production. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:8357–8367. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Huang H, Moll J, Thauer RK. NADP+ reduction with reduced ferredoxin and NADP+ reduction with NADH are coupled via an electron-bifurcating enzyme complex in Clostridium kluyveri. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5115–5123. doi: 10.1128/JB.00612-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeidan AA, Van Niel EW. A quantitative analysis of hydrogen production efficiency of the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor owensensis OLT. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010;35:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.11.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soboh B, Linder D, Hedderich R. A multisusbunit membrane-bound [NiFe] hydrogenase and an NADH-dependent Fe-only hydrogenase in the fermenting bacterium Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Microbiology. 2004;150:2451–2463. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veit A, Akhtar MK, Mizutani T, Jones PR. Constructing and testing the thermodynamic limits of synthetic NAD(P)H: H2 pathways. Microb Biotechnol. 2008;1:382–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2008.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhaart MR, Bielen AA, van der Oost J, Stams AJ, Kengen SW. Hydrogen production by hyperthermophilic and extremely thermophilic bacteria and archaea: mechanisms for reductant disposal. Environ Technol. 2010;31:993–1003. doi: 10.1080/09593331003710244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foglia D, Wukovits W, Friedl A, de Vrije T, Claassen P. Fermentative hydrogen production: influence of application of mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria on mass and energy balances. Chem Eng Trans. 2011;25:815–820. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hema R, Agrawal P. Production of clean fuel from waste biomass using combined dark and photofermentation. IOSR J Comput Eng. 2012;1:39–47. doi: 10.9790/0661-0143947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peixoto G, Pantoja-Filho JLR, Agnelli JAB, Barboza M, Zaiat M. Hydrogen and methane production, energy recovery, and organic matter removal from effluents in a two-stage fermentative process. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;168:651–671. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9807-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seol E, Ainala SK, Sundara Sekar B, Park S. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli strains for co-production of hydrogen and ethanol from glucose. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2014;39:19323–19330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.06.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundara Sekar B, Seol E, Raj SM, Park S. Co-production of hydrogen and ethanol by pfkA-deficient Escherichia coli with activated pentose-phosphate pathway: reduction of pyruvate accumulation. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:95–106. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0510-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazdani SS, Gonzalez R. Engineering Escherichia coli for the efficient conversion of glycerol to ethanol and co-products. Metab Eng. 2008;10:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seol E, Sundara Sekar B, Raj SM, Park S. Co-production of hydrogen and ethanol from glucose by modification of glycolytic pathways in Escherichia coli—from Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway to pentose phosphate pathway. Biotechnol J. 2015;11:249–256. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chemler JA, Fowler ZL, McHugh KP, Koffas MA. Improving NADPH availability for natural product biosynthesis in Escherichia coli by metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2010;12:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siedler S, Bringer S, Polen T, Bott M. NADPH-dependent reductive biotransformation with Escherichia coli and its pfkA deletion mutant: influence on global gene expression and role of oxygen supply. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:2067–2075. doi: 10.1002/bit.25271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Seol E, Oh YK, Wang GY, Park S. Hydrogen production and metabolic flux analysis of metabolically engineered Escherichia coli strains. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2009;34:7417–7427. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.05.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko Y, Ashok S, Seol E, Ainala SK, Park S. Deletion of putative oxidoreductases from Klebsiella pneumoniae J2B could reduce 1,3-propanediol during the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glycerol. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2015;20:834–843. doi: 10.1007/s12257-015-0166-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiner D, Paul W, Merrick MJ. Construction of multicopy expression vectors for regulated over-production of proteins in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other enteric bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1779–1784. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou S, Ainala SK, Seol E, Nguyen TT, Park S. Inducible gene expression system by 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:169–176. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0353-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moritz B, Striegel K, de Graaf AA, Sahm H. Kinetic properties of the glucose-6-phosphate and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenases from Corynebacterium glutamicum and their application for predicting pentose phosphate pathway flux in vivo. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:3442–3452. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruger NJ. The Bradford method for protein quantitation. In: Walker JM, editor. The protein protocols handbook, Chapter 4. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc.; 2009. p. 17–24.

- 26.Duffieux F, Van Roy J, Michels PA, Opperdoes FR. Molecular characterization of the first two enzymes of the pentose-phosphate pathway of Trypanosoma brucei. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconolactonase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27559–27565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stryer L, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL. The calvin cycle and pentose phosphate pathway. In: Biochemistry, Chapter 20, 7th edn. W. H. Freeman and Company New York; 1995. p. 589–614.

- 28.Leonardo MR, Dailly Y, Clark DP. Role of NAD+ in regulating the adhE gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6013–6018. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6013-6018.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashok S, Raj SM, Ko Y, Sankaranarayanan M, Zhou S, Kumar V, et al. Effect of puuC overexpression and nitrate addition on glycerol metabolism and anaerobic 3-hydroxypropionic acid production in recombinant Klebsiella pneumoniae ΔglpKΔdhaT. Metab Eng. 2013;15:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olavarría K, Valdés D, Cabrera R. The cofactor preference of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli–modeling the physiological production of reduced cofactors. FEBS J. 2012;279:2296–2309. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauer U, Canonaco F, Heri S, Perrenoud A, Fischer E. The soluble and membrane-bound transhydrogenases UdhA and PntAB have divergent functions in NADPH metabolism of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6613–6619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scopes RK, Testolin V, Stoter A, Griffiths-Smith K, Algar EM. Simultaneous purification and characterization of glucokinase, fructokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Zymomonas mobilis. Biochem J. 1985;228(3):627–634. doi: 10.1042/bj2280627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy HR, Vought VE, Yin X, Adams MJ. Identification of an arginine residue in the dual coenzyme-specific glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides that plays a key role in binding NADP+ but not NAD+ Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;326:145–151. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vought V, Ciccone T, Davino MH, Fairbairn L, Lin Y, Cosgrove MS, et al. Delineation of the roles of amino acids involved in the catalytic functions of Leuconostoc mesenteroides glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15012–15021. doi: 10.1021/bi0014610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tonouchi N, Sugiyama M, Yokozeki K. Coenzyme specificity of enzymes in the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway of Gluconobacter oxydans. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:2648–2651. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Details of Zwf and Gnd used in this study. Table S2. Kinetic properties of Zwf and Gnd used in this study. Figure S1. Adaptive evolution for anaerobic growth of SH5Δpgi with glucose as substrate. Figure S2. Anaerobic growth of recombinant SH5ΔpgiΔedd strains on glucose (Glu) and gluconate (Gln). Refer to Table 1 for the genotype of each strain. Figure S3. Growth and acetate production yield of SH5ΔpgiΔedd and SH5ΔpgiΔedd_ZG on glucose in the presence of nitrate. Figure S4. Theoretical prediction of relation between dependence on ED pathway and ethanol and acetate production. Redox-imbalanced region denotes the production of excess NADPH than pyruvate. Figure S5. SDS-PAGE analyses of Zwf (55 kDa) and Gnd (51 kDa) in soluble fraction SH5_pDK7_zwf (Lane 1) and SH5_pDK7_gnd (Lane 2) and purified Zwf (Lane 3) and Gnd (Lane 4) by Ni–NTA chromatography. Figure S6. Growth and metabolites production yield of SH5Δpgi_ZGU and SH5ΔpgiΔudhAΔpntA_ZG on glucose.

Additional file 2: Appendix A. Raw data of RT-PCR analysis.