Abstract

The middle ear conducts sound to the cochlea for hearing. Otitis media (OM) is the most common illness in childhood. Moreover, chronic OM with effusion (COME) is the leading cause of conductive hearing loss. Clinically, COME is highly associated with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia, implicating significant contributions of cilia dysfunction to COME. The understanding of middle ear cilia properties that are critical to OM susceptibility, however, is limited. Here, we confirmed the presence of a ciliated region near the Eustachian tube orifice at the ventral region of the middle ear cavity, consisting mostly of a lumen layer of multi-ciliated and a layer of Keratin-5-positive basal cells. We also found that the motile cilia are polarized coordinately and display a planar cell polarity. Surprisingly, we also found a region of multi-ciliated cells that line the posterior dorsal pole of the middle ear cavity which was previously thought to contain only non-ciliated cells. Our study provided a more complete understanding of cilia distribution and revealed for the first time coordinated polarity of cilia in the epithelium of the mammalian middle ear, thus illustrating novel structural features that are likely critical for middle ear functions and related to OM susceptibility.

Otitis media (OM), or inflammation of the middle ear, is the most commonly cited reason for visits to pediatricians1. Chronic otitis media with effusion (COME) is the leading cause of conductive hearing loss2,3,4,5. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic condition, about one in 10,000–30,000 individuals, which affects the function of motile cilia, and manifests as persistent secretion retention and chronic infection in the middle ear, nose and facial sinuses6,7,8,9. About 50% of the pediatric PCD cases were first suspected in ENT clinics during visits for COME6,7,9,10,11,12. The significant association between COME and PCD implicates the predilection of cilia dysfunction to COME and conductive hearing loss.

Despite the potentially significant role that cilia may play in middle ear function and pathology, ciliation in the middle ear epithelium is not well understood13,14,15,16,17. A recent study used genetic tracing tools to illustrate the dual origin of the epithelium lining the mammalian middle ear cavity, and determined the developmental timeline of the maturation of the middle ear cavity in mice17,18,19. While the epithelial cells lining the dorsal region of the middle ear cavity are derived from neural crests, the epithelium covering the ventral region of the middle ear cavity is formed from the endoderm-originated 1st pharyngeal pouch17,18,19. Examination of the expression of acetylated α-tubulin, which is enriched in cilia axonemes, and of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provided general divisions of ciliated and non-ciliated regions in the middle ear epithelium17. These data together suggest that the epithelium derived from the endoderm which covers the ventral region of the middle ear cavity near the Eustachian tube orifice is ciliated, while the epithelium derived from the neural crests which lines the dorsal region of the middle ear cavity is not ciliated17.

The polarity or the orientation of motile cilia critically underlies normal cilia functions20,21,22,23,24,25. In the trachea, motile cilia adorn the surface of epithelial cells and are uniformly oriented, which drives a directional outward flow that is critical for mucociliary clearance23,26,27. In the brain ventricles, motile cilia are also uniformly oriented to drive a directional cerebrospinal fluid flow that provides directional cues for brain development and is required for normal spine curvature23,28,29,30,31. The uniform orientation of motile cilia in these tissues is a manifestation of planar cell polarity (PCP)26,32,33,34,35,36, which refers to the coordinated polarization of cells along the plane of the tissue. The polarity and the beating direction of each cilium are dictated by the position and orientation of the basal body21,23,27,37,38. The basal body is a mother centriole-derived nine triplet (9 × 3) microtubule structure that acts as the foundation to the motile cilia axoneme, which consists of nine doublet (9 × 2) microtubules along with a central microtubule pair (9 × 2 + 2)21,37. In addition to the microtubules, the basal body consists of an appendage structure, the basal foot, which marks the orientation of the cilium and is composed of specific proteins that are electron dense on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs21,27,38,39. The polarity information of the motile cilia in the middle ear epithelium is unknown.

Here, we report on the distribution of cilia and the polarity of cilia in the mature mouse middle ear epithelium. We confirmed that the epithelium near the Eustachian tube orifice, which is developed from the endoderm-originated 1st pharyngeal pouch17, is ciliated. We found that these cilia are coordinately oriented toward the Eustachian tube orifice. Surprisingly, we also found a second population of ciliated cells in the epithelium lining the middle ear cavity. This second population of ciliated epithelial cells cover the dorsal region of the middle ear cavity within the epithelium derived from neural crests17. This population of ciliated cells have the same composition of Keratin 5-posive basal cells and Keratin 5-negative multi-ciliated cells normally observed in the multi-ciliated mucosa40,41,42,43, including the middle ear ciliated epithelium near the Eustachian tube orifice. The cells in the non-ciliated epithelial regions are Keratin 5-positive. They form a thin, singular layer of cells which line the middle ear cavity between the two regions of ciliated cells at the ventral and dorsal poles of the middle ear cavity. These results provide new insights into the potential functions of cilia in the middle ear, and point to the importance of not only cilia but also cilial polarity in both the normal functioning and pathogenesis of the middle ear.

Results

Dual populations of ciliated cells in the mouse middle ear epithelium

During development, the endoderm-originated 1st pharyngeal pouch extends to give rise to the epithelial layer of the Eustachian tube and the epithelial lining of the ventral region of the middle ear cavity, or the tympanic cavity, in mice17. The epithelial lining of the dorsal region of the middle ear cavity is derived from neural crest cells that fuse with the ruptured extending Eustachian tube during development17. By postnatal day 17 (P17) in mice, the formation of the middle ear cavity is complete. The fully formed middle ear cavity is covered with epithelial cells derived from both neural crests and the endoderm at its dorsal and ventral regions, respectively17.

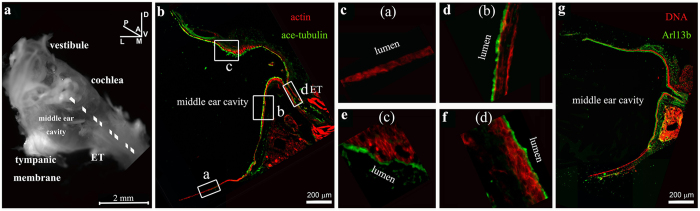

We examined ciliation in mature mouse middle ears (Figs 1 and 3, S1). We isolated temporal bones from P30-P120 mice, decalcified the samples, prepared oblique transverse cryosections of the temporal bones (Fig. 1a), and stained the sections with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin that was enriched in cilia axoneme44 (Figs 1b–f and 2, S1) and an antibody against Arl13b (Fig. 1g) that was localized to the cilia axoneme45. As expected17, the epithelium lining the ventral region of the middle ear cavity near the Eustachian tube orifice and the epithelium of the Eustachian tube were positive for acetylated α-tubulin and ciliated (Fig. 1b,d,e), while areas away from the Eustachian tube orifice (Figs 1b,c and 2, S1) were not ciliated. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) similarly revealed that the epithelium lining of the ventral region of the middle ear cavity near the Eustachian tube was ciliated (Fig. 3a–c).

Figure 1. Cilia in the ventral region of the epithelial lining of the middle ear.

(a) A dissected right temporal bone illustrates the relative position of the Eustachian tube (ET), the inner ear (cochlea and vestibule), the middle ear cavity, and the tympanic membrane. The cryosection plane is denoted by the dashed line. The inner ear is on the other side the medial wall of the middle ear cavity and is dorsal to the Eustachian tube, while the tympanic membrane is on the lateral side of the middle ear cavity. The vestibular structure is dorsal to the cochlea in the inner ear. The orientation designations are: L-lateral; M-medial; V-ventral; D-dorsal; A-anterior; P-posterior. Scale: 2 mm. (b–g) Temporal bone cryosections staining with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin (green) and phalloidin (red) for actin (b–f), or an antibody against Arl13b (green) and Hoechst for DNA (red) (g). Panels c-f represent the larger views of the boxed regions (a–d) in b, in the epithelium of the middle ear at the areas of the tympanic membrane (a), ventral regions near the ET (b) and (c), or in the ET (d). The ciliated areas consist of a lumen staining for acetylated α-tubulin that is enriched in the cilia axoneme. The ciliation pattern in the middle ear revealed by acetylated α-tubulin staining (b) was validated by Arl13B staining (g), which marks the axoneme. Scale (b,g): 200 μm.

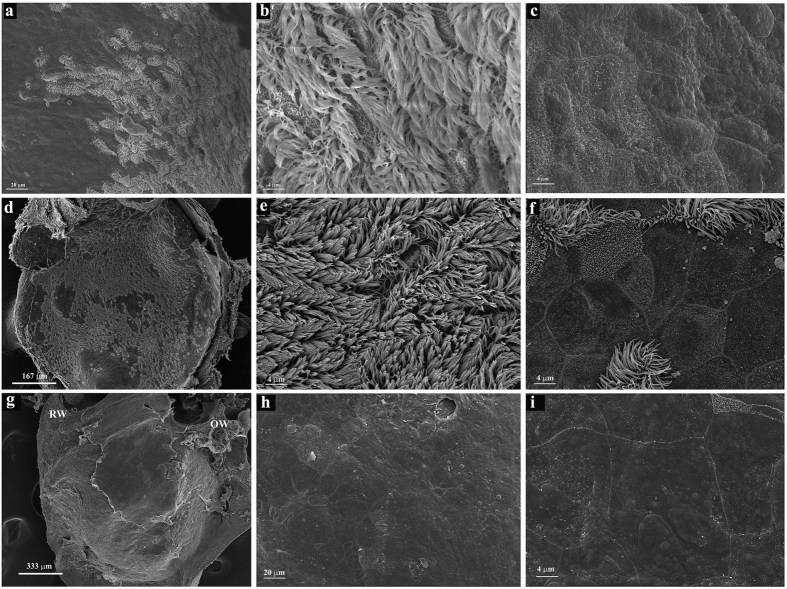

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy of the middle ear epithelium.

(a–c) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the middle ear from an adult mouse (4 months old) near the orifice of the Eustachian tube, which is located outside the right bottom corner of the image (a). The region consists of mostly multi-ciliated cells (b), and is bordered by non-ciliated cells on the lateral wall of the tympanic or middle ear cavity (c). Scale bars: 20 μm (a), 4 μm (b,c). (d–f) SEM of the posterior dorsal roof regions of the middle ear cavity above the round window. Extensive ciliation was observed in the region (d–f). Scale bars: 167 μm (d), 4 μm (e), 4 μm (f). (g–i) The region lining the promontory of the cochlea, or the bulging of the medial wall of the tympanic cavity produced by the cochlea, which is medial and ventral to the dorsal roof of the middle ear cavity, is not ciliated and shares similarity to the non-ciliated region on the lateral wall of the tympanic cavity. The round window (RW) is posterior to the oval window (OW). The roof region dorsal to the round window is the region shown in (d–f). Scale bars: 333 μm (g), 20 μm (h), 4 μm (i).

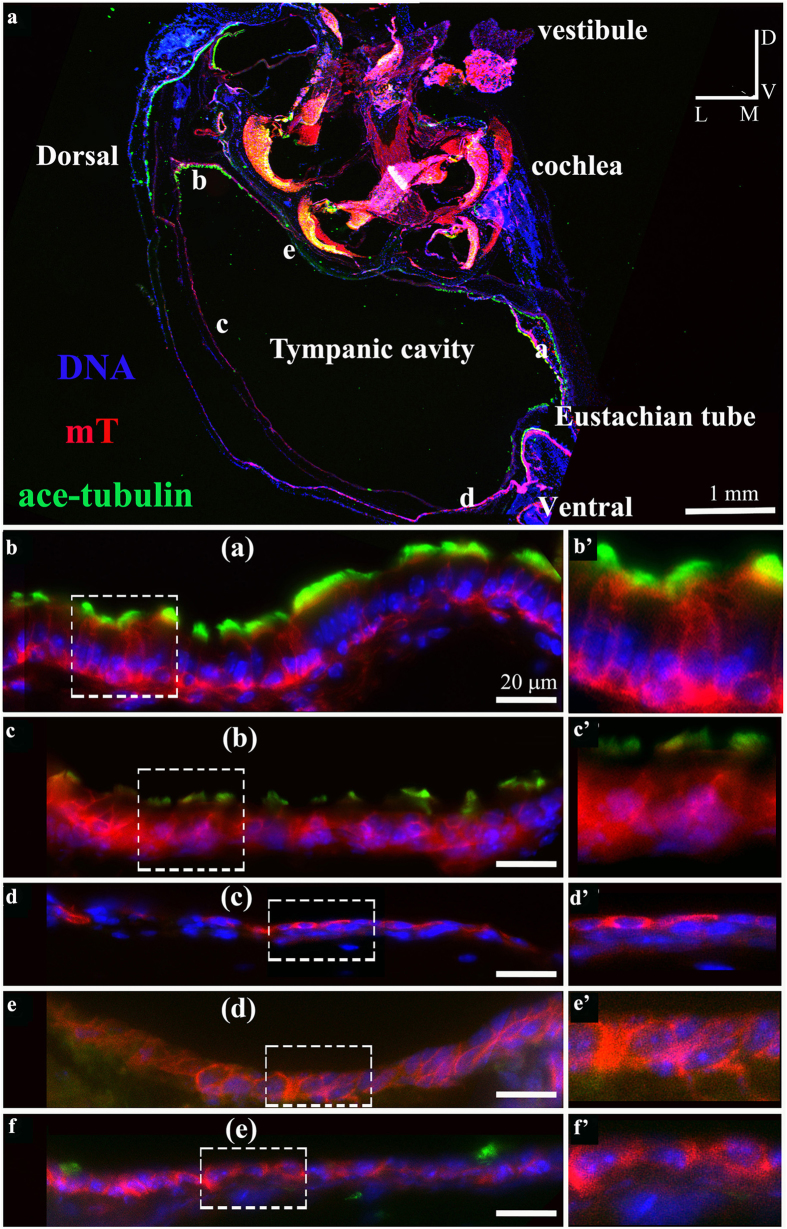

Figure 2. Dual ciliated regions in the epithelium that lines the middle ear cavity.

(a–f) A temporal bone from an adult mouse expressing the red fluorescent protein membrane Tomato protein (mT) was cryo-sectioned and staining for cilia using an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin (green) and DNA (Hoechst, blue). Ciliation was detected in both the ventral region and the dorsal region of the epithelium that lines the middle ear cavity. Panels (b) to (f) correspond to regions (a–e) in (a). (b’)–(f’) are larger views of the boxed regions in corresponding (b)–(f). The presence of cilia in the dorsal region was verified by examination of serial sections (Fig. S1). Scale: 1 mm (a) and 20 μm (b–f). The orientation designations in (a) are: L-lateral; M-medial; V-ventral; D-dorsal.

The epithelial cells that line the ventral region of the middle ear cavity near the Eustachian tube derive from the endoderm during development17. Our data on ciliation patterns in this region is consistent with that found in previous reports14,16, which point to the idea that endoderm-derived cells in the middle ear epithelium are ciliated17. It is thought that the epithelial cells lining the dorsal region of the middle ear cavity, which derive from neural crest cells, are not ciliated17. Surprisingly, however, we observed ciliation in this region (Fig. 2). We verified ciliation in the epithelium that lines the dorsal region of the middle ear cavity by examination of multiple serial sections (Fig. S1), and SEM (Fig. 3d–i). The epithelium lining the dorsal roof of the middle ear cavity above the round window is extensively ciliated (Fig. 3d–f), while the epithelial cells lining the medial wall of the middle ear cavity are not ciliated (Fig. 3g–i).

Coordinated orientation of cilia in the mouse middle ear epithelium

In the respiratory epithelium of the trachea, motile cilia are aligned uniformly to generate a directional beating motion across the mucosal tissue for clearance21,22,46. Although the polarity of the motile cilia in the nasal epithelium has not been examined directly, their motility and kinetics47,48,49,50,51 suggest that cilia in the nasal respiratory epithelium are likely also aligned to generate synchronized beating waves for mucociliary clearance functions. Accordingly, it has been generally accepted that the cilia in the respiratory epithelia share common structural features - coordinated motility or polarity of the cilia in the respiratory epithelia – to allow for clearance functions. However, as with the nasal respiratory epithelium, the polarity of the cilia in the middle ear has not been directly examined.

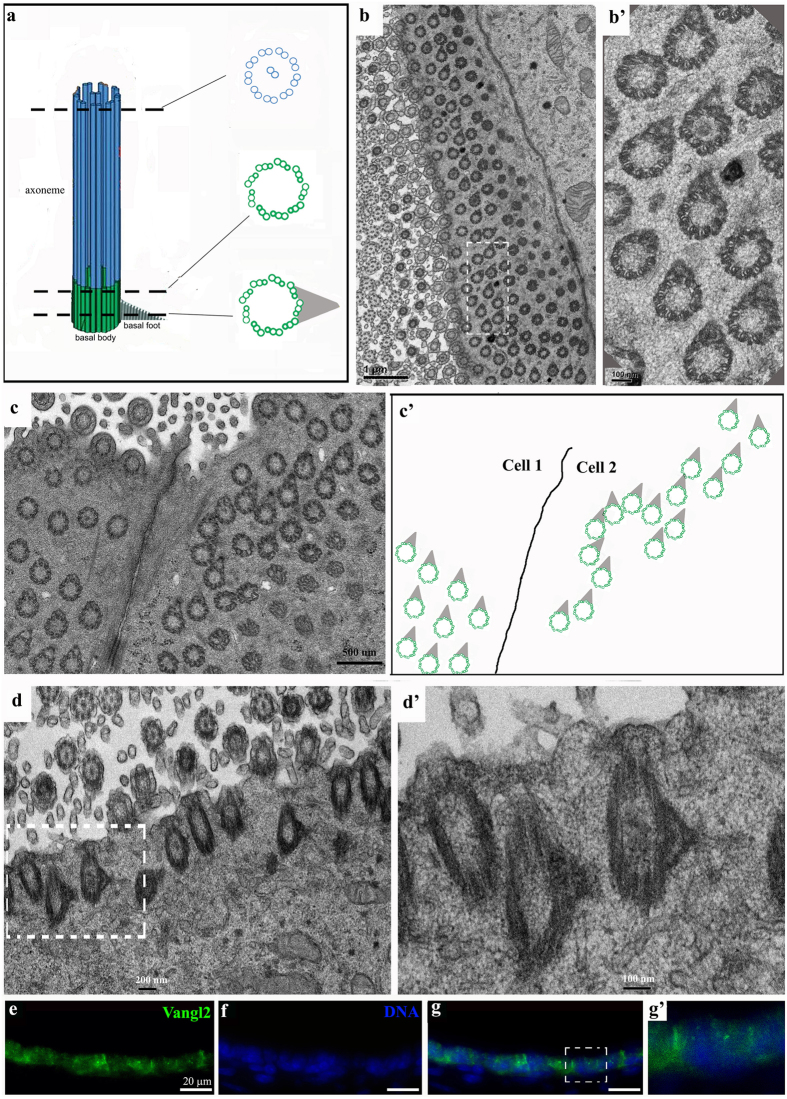

The polarity of motile cilia could be visualized by TEM of the electron dense accessory proteins in the basal foot of the basal body21,27,37 (Fig. 4a). We processed mouse temporal bones for thin sections along the horizontal plane and the vertical plane of the epithelium, and examined the sections using TEM (Fig. 4). The core microtubule structure in the axoneme portion of the motile cilia consist of nine doublets as well as a central pair, or 9 × 2 + 2 microtubules, while the microtubule structure in the basal body consists of nine triplets without the central pair, or 9 × 3 + 0 microtubules52 (Fig. 4a). Moreover, at the basal foot level, the basal body appears as a ring of nine triplets with an electron-dense triangle as visualized by TEM (Fig. 4). As revealed by TEM through the horizontal plane of the epithelium, the motile cilia in the middle ear epithelium near the Eustachian tube are oriented toward the same direction (Fig. 4b,b’). Similarly, the motile cilia in the middle ear epithelium at the dorsal roof of the middle ear cavity are also oriented toward the same direction (Fig. 4c,c’). The uniform orientation of motile cilia was also observed in TEM of vertical sections (Fig. 4d,d’).

Figure 4. Planar cell polarity of the motile cilia in the middle ear.

(a) Diagram of microtubules and the basal body of a motile cilium. The ciliary axoneme consists of nine tubulin doublets and a central pair of tubulin doublets that is the hallmark of a motile cilium. The basal body is made up of nine tubulin triplets. At the level of the basal foot, accessory proteins compose a triangular electron-dense structure on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) graphs, which marks the orientation of the cilium. (b–d) Horizontal (b,b’,c,c’) and vertical (d,d’) TEM micrographs of the middle ear epithelium. TEM through the basal foot level revealed that cilia are oriented toward the same direction (b–d). b’ and d’ are a large view of the boxed regions in (b and d) respectively. (c’) marks the orientation of basal feet when their orientation was visible in c. Scale bars: 1 μm (b), 100 nm (b’), 500 nm (c), 200 nm (d) and 100 nm (d’). (e–g) A cryosection of the middle ear staining with an antibody against Vangl2 (green) and DNA (Hoechst, blue). (g’) is a larger view of the boxed region in (g). Vangl2 is enriched at the apical cortex. Scale: 20 μm.

The coordinated orientation of cells or cilia is a manifestation of planar cell polarity (PCP), and involves a set of conserved genes known as core PCP genes20,32,53. In particular, Vangl2 has been shown to be involved in all known PCP processes20,32,54,55. For PCP regulation in epithelial tissues, Vangl2 and other membrane or membrane-associated essential PCP proteins form membrane complexes at the cell-cell junction to coordinate the polarity of neighboring cells36,56,57,58. Indeed, Vangl2 is expressed in the middle ear epithelium (Fig. 4e–g,g’), and Vangl2 protein was localized to the apical cell-cell contacts in the ciliated epithelial cells in the middle ear (Fig. 4g’).

Keratin 5 labels the basal cells of the ciliated regions, Goblet cells, and the non-ciliated cells in the middle ear epithelium

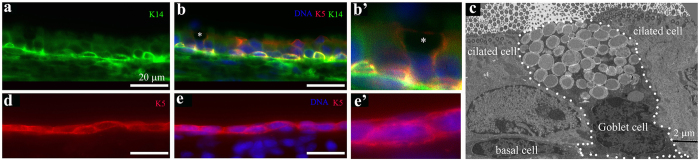

The cells lining the middle ear cavity appear to consist of two general epithelial types. The first is the ciliated epithelium, consisting mostly of a lumen layer of multi-ciliated cells and a basal layer of cells, while the second is the non-ciliated epithelium, consisting of a thin layer of squamous cells (Figs 1 and 3, S1). In the trachea and nasal mucosal epithelia, the basal layer of cells (aka “basal cells”), express the precursor-specific intermediate filament protein Keratin 5 and act as the precursor or the stem cells of the epithelia to give rise to and replenish the terminally differentiated multi-ciliated cells40,41,42,43. Similarly, Keratin 5 was observed in the basal cells of the ciliated epithelium in the middle ear (Fig. 5a,b and b’). It is also expressed in the Goblet cells within the ciliated region (Fig. 5a,b, and b’). Goblet cells were identified by their distinct stratified and goblet-shaped morphology in cryo-sections (Fig. 5a,b,b’) and by the presence of numerous secretory vesicles on TEM graphs (Fig. 5c). It is noted that previous studies have reported various characterizations of secretory cells in the middle ear epithelium, including Goblet cells and dark granulated cells59,60. Moreover, Keratin 5 is also expressed in the non-ciliated squamous epithelial cells in the middle ear (Fig. 5d,e,e’). Interestingly, while Keratin 14 is also expressed in the basal cells (Fig. 5a,b,b’) and the non-ciliated epithelial cells17, it is not in the Goblet cells (Fig. 5a,b,b’).

Figure 5. Keratin 5 positive cells in the epithelium lining of the middle ear cavity.

(a–c) A cross section in the ciliated epithelium of the middle ear cavity, showing the presence of basal cells that are positive for Keratin 5 (K5, red)) and Keratin 14 (K14, green) (a,b,b’). DNA was stained by Hoechst (blue). (b’) is a larger view of a region in (b) marked by a * that appears to be a Goblet cell. Note that K5 also labeled the apparent Goblet cell while K14 did not. A TEM graph of the ciliated epithelium region revealed the high resolution cellular structure of the epithelium, consisting of the basal, ciliated, and Goblet cells (c). Note the distinct “goblet”-shaped morphology (b,b’,c) and the presence of numerous secretory vesicles in the Goblet cell (c). Note also that the Goblet cells do not contain cilia basal bodies or axoneme (b,b’,c), while thinner sections of microvilli of the Goblet cell are visible (c). Scale: 20 μm (a,b); 2 μm (c). (d–e) A cross section in the non-ciliated epithelium of the middle ear cavity, revealing a single layer of squamous epithelial cells that are positive for Keratin 5. (e’) is a larger view of a region in (e) Scale: 20 μm.

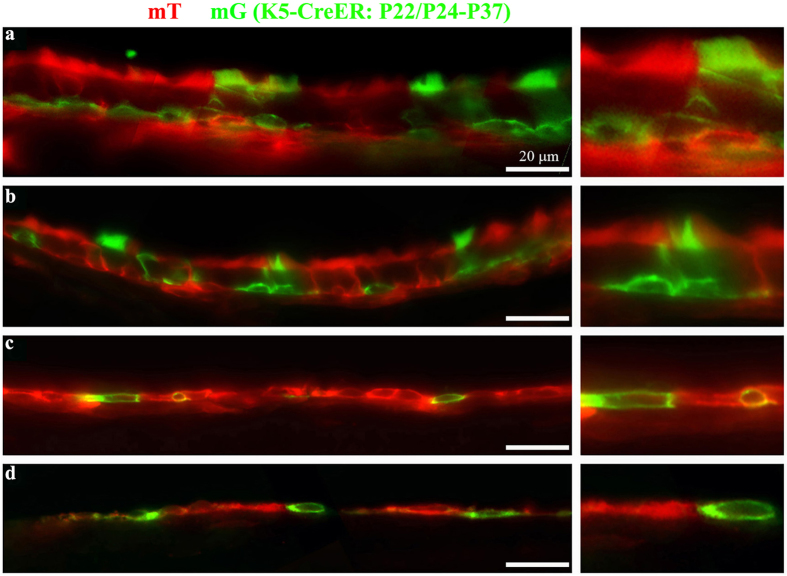

We further used the Keratin 5-CreER line61 crossed with a reporter line, mT/mG62, to verify the presence of Keratin 5+ cells and trace Keratin 5+ cells in both the ciliated and non-ciliated epithelia (Fig. 6). We injected tamoxifen at P22 and P24, and collected the temporal bones at P37. The activation of CreER upon tamoxifen injections results in the conversion of membrane Tomato protein (mT) to membrane GFP (mG) in Keratin 5+ cells61,62. We observed GFP+ -basal cells and GFP+-ciliated cells in both ciliated regions of the epithelium lining the middle ear cavity (Fig. 6a,b). We also observed GFP+ cells in the non-ciliated regions (Fig. 6c,d). The data confirmed that Keratin 5+ basal cells give rise to ciliated cells in the two ciliated regions in the middle ear (Fig. 6a,b), and that Keratin 5+ squamous cells in the single cell layer of the non-ciliated epithelium of the middle ear replenish the epithelial cells in those regions (Fig. 6c,d).

Figure 6. Keratin 5 positive cells replenish the ciliated and non-ciliated cells in the epithelium that lines the middle ear cavity.

(a–d) Mice positive for Keratin 5 (K5) Cre-ER and mT/mG transgenes were injected with Tamoxifen at postnatal days 22 (P22) and P24. The temporal bones were collected at P37 and processed for visualization of the native mT and mG signals. Panels a-d represent regions in the epithelium from the ventral region near the orifice of the Eustachian tube (a), the dorsal ciliated region (b), the non-ciliated region against the inner ear (c), and the non-ciliated region against the tympanic membrane (d). Note that the basal cells are with a flat morphology at the basal layer of the epithelium, and that some ciliated cells are green, indicating their K5-positive origin. Scale: 20 μm.

Discussion

Motile cilia can provide motility for the cells, or generate a directional flow of the media across the tissues to provide directional cues or carry out clearance functions20,21,23,25. In the respiratory epithelium of the trachea, motile cilia are uniformly orientated to generate an outward flow for mucociliary clearance27. Cilia dysfunctions have been implicated in a number of conditions, including neonatal respiratory distress, chronic nasal congestion, bronchiectasis and sinusitis, and chronic otitis media with effusion6,7,8,10,11,12,63,64,65,66. Despite the significant association and likely contributory role of cilia in OM6,7,11,12,63,66,67, the most common childhood disease, only a sparse number of studies examined ciliation in the epithelium that lines the middle ear cavity and thus have provided only a partial understanding of ciliation in the middle ear13,14,16,17,68,69,70. Moreover, the orientation of the cilia, which is the structural feature of cilia critical to their motility output and clearance function, has not even been studied. In this study, we characterize ciliation in the epithelium that lines the middle ear cavity, and examine the orientation of these motile cilia of the middle ear.

We confirmed the presence of ciliation in the epithelial region near the orifice of the Eustachian tube at the ventral side of the middle ear (Figs 1 and 3, S1). We showed that this epithelium is made of typical Keratin 5+ basal cells and the lumen layer of multi-ciliated cells (Figs 5 and 6), and that the Keratin 5+ basal cells give rise to the lumen layer of ciliated cells (Fig. 6). Furthermore, we showed for the first time that the motile cilia in the region are aligned toward the general direction of the opening of the Eustachian tube (Fig. 4), and the planar cell polarity (PCP) protein Vangl2 is expressed in the ciliated epithelium (Fig. 4).

Moreover, we also identified a new population of ciliated cells in the epithelium lining the middle ear cavity. We found that the epithelial region at the dorsal roof of the middle ear cavity above the oval window is also ciliated via the examination of multiple serial sections (Figs 1 and 2, S1, 5, 6). The ciliated epithelium in the dorsal region also consists of Keratin 5+ basal cells and a lumen layer of multi-ciliated cells, and the Keratin 5+ basal cells give rise to the lumen ciliated cells (Figs 5 and 6). It would be of interest to explore the capability and time course of replenishment of ciliated cells by Keratin 5+ basal cells during pathology of the middle ear. Cell lineage determination using neural crest-specific and endoderm-specific Cre mouse strains in combination with a reporter strain indicated that the epithelium in the dorsal region derive from the neural crests while the epithelium in the ventral region originates from the endoderm17. Our data suggested that the neural crest derived epithelium in the middle ear could also develop into a typical mucosal epithelium that consists of a basal cell layer and a ciliated cell layer. Alternatively, the dorsal roof region above the round window is a continuation of the endoderm-derived epithelial region, as the determination of the exact boundaries of the two-lineage-derived epithelia may not be available due to limitations of markers and lineage tracing tools.

The significance of dual regions or extended regions of ciliated cells in the middle ear cavity at two poles of the middle ear cavity is perhaps two-fold. Firstly, the normal functions of the middle ear cavity include balancing air pressure and conducting sound signals to the inner ear71,72. The presence of motile cilia at the two poles of the middle ear cavity may present mechanical advantages for the efficacy of air flow and middle ear ossicle conductance of mechanical sound signals. Secondly, the same mechanical advantage afforded by the presence of cilia at the two poles of the middle ear cavity may also be beneficial for fluid and pathogen clearance from the middle ear.

In addition to functions associated with cilia motility, cilia in the human airway epithelia could also function in chemosensory-based defense mechanisms73,74,75. It will be of great interest to determine whether cilia in the middle ear also express chemosensory receptors and whether the two populations of ciliated cells in the middle ear have differential expressions of chemosensory receptors and act differentially in chemosensory related mechanisms.

The demonstration of motile cilia PCP in the middle ear points to the possibility that defective PCP signaling may lead to respiratory diseases and chronic OM with effusion, which is commonly associated with PCD and other ciliopathy diseases6,7,12,64,65,66,76,77. Our study supports the justification to expand upon the capacity of current tests for PCD and other ciliopathy-related diseases, which are considered to significantly underestimate the cases, to include the ability to reveal defects in PCP genes and cilia polarity10,65,77,78. The inclusion of PCP and cilia polarity genes in the genetic and pathological-morphological tests will likely lend support to the idea of PCP genes as a novel class of susceptibility genes for COME and other respiratory diseases, caused by a reduction or ablation of mucociliary functions of the motile cilia.

Methods

Animals

Wild type mice, mice carrying a mT/mG transgene or the Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)/Luo/J (Jackson Laboratory stock#: 007576; mT/mG)62, and mice carrying K5-Cre-ERT2 transgene or Tg(KRT5-cre/ERT2)2lpc/JeldJ (Jackson Laboratory stock#: 018394; K5-Cre-ERT2)61 were used. Animal care and use was in accordance with NIH guidelines and was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University.

Dissection of temporal bones, decalcification, and cryo-sectioning

The temporal bones of mice were dissected, and fixed in 4% PFA. The fixed temporal bones were decalcified in 10% EDTA for 24 hours or longer at 4° C. The decalcified samples were cryo-protected in 30% sucrose, embedded in OCT, and sectioned at 12 μm in thickness along an oblique transverse plane as diagramed in Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry on cryosections

Immunostaining and imaging were performed as previously described36,79. Briefly, the sections were rehydrated, blocked with 10% donkey serum at room temperature for 30 minutes or longer, incubated with primary antibodies in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST) overnight at 4° C, washed in PBST for three times at room temperature, incubated with appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hour or longer, and mounted in Fluro-G (SouthernBiotech) for imaging. An inverted Olympus IX71 microscope or Zeiss confocal microscope was used for imaging.

The primary antibodies used were mouse against acetylated α-tubulin (Sigma, Cat#: T7451, 1:400), rabbit against Arl13b (gift from Tamara Caspary, Emory University, USA, 1:500)45, rabbit against Keratin 5 (BioLegend, Cat#: 905501, 1:500), mouse against Keratin 14 (ThermoFisher, Clone LL004, Cat#: MS-115-P0, 1:1000), and sheep against Vangl2 (R&D systems, Cat#: AF4815, 1:200). For staining with antibodies against Keratin 5, Keratin 14, and Vangl2, the sections were pretreated with an antigen retrieve procedure by incubating the sections in 10 mM citric buffer (pH 6.0) in a steamer for 10 minutes. In addition, Hoechst (ThermoFisher, Cat#: 33342, 1:10000) staining of DNA was included in most staining procedures to outline the cell layers in epithelia.

The antibody specificity for each of the antibodies for the specific cellular compartment(s) was confirmed using the corresponding pre-immune serum and by staining with cochleae and respiratory epithelia in the nose and trachea, in which the specificity of these antibodies has been demonstrated in numerous published studied including the studies using antibodies against Vangl280, acetylated α-tubulin and Arl13b36,45, and Keratin 5 and Keratin 1442,81,82.

Keratin 5-positive cell tracing

Animals carrying K5-CreERT;mT/mG were injected with Tamoxifen at postnatal day 22 (P22) and P24. Animals were sacrificed at P37. Temporal bones were collected and processed for cryosection and imaging of mT and mG native signals of the sections.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Temporal bones were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Samples were then washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer followed by the post fixation with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 hour. After washing with de-ionized water, samples were dehydrated through an ethanol series and eventually placed in 100% ethanol. Samples were then placed into labeled specimen capsules and transferred to a sample holder filled with fresh 100% dry ethanol. The sample holder was placed into a pre-chilled Polaron E3000 critical point drying (CPD) unit and sealed. The CPD unit was filled with liquid carbon dioxide, which gently flowed through the chamber until the ethanol had been replaced with liquid carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide was brought to its critical point of 1073 psi and 31 °C and allowed to gently bleed away. The dry samples were secured to labeled SEM stubs and sputter coated with 15 nm gold palladium using a Denton Vacuum Desk II sputter coater. The samples were imaged using a Topcon DS150 field emission scanning electron microscope at 10 kV.

For TEM, temporal bones were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Samples from older mice were decalcified in 10% EDTA for a few days after fixation. Samples were then washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour. After washing with de-ionized water, samples were dehydrated through an ethanol series to 100% ethanol, infiltrated with Eponate 12 resin (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA), placed in labeled Beam capsule with resin, and then polymerized in a 60 °C oven. Ultrathin sections were cut at 70–80 nanometer thick on a Leica UltraCut Sultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL). Grids with ultrathin sections were stained with 5% uranyl acetate and 2% lead citrate. Ultrathin sections were imaged on a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Gatan US1000 CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Luo, W. et al. Cilia distribution and polarity in the epithelial lining of the mouse middle ear cavity. Sci. Rep. 7, 45870; doi: 10.1038/srep45870 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions W.W.L., J.T., H.Y., K.K. performed experiments. W.W.L. and P.C. planned the project and the experiments, discussed the results, and completed the manuscript. P.C. directed and supervised the entire project. J.D.L., F.L.C., N.W.T., X.L., and D.D.R. participated in discussion of the project and the manuscript. F.L.C., X.L., and D.D.R. also provided financial support for the project.

References

- Schilder A. G. et al. Otitis media. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16063 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman M. Conductive deafness in children. N Z Med J 65, 118–119 (1966). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handzic J. et al. Hearing in children with otitis media with effusion--clinical retrospective study. Coll Antropol 36, 1273–1277 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Zaidi S. S., Pasha H. A., Suhail A. & Qureshi T. A. Frequency of Sensorineural hearing loss in chronic suppurative otitis media. J Pak Med Assoc 66(Suppl 3), S42–S44 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehudai N., Most T. & Luntz M. Risk factors for sensorineural hearing loss in pediatric chronic otitis media. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 79, 26–30 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie P. H. et al. Presentation of primary ciliary dyskinesia in children: 30 years’ experience. Journal of paediatrics and child health 51, 722–726 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L. C. & Birman C. S. The impact of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia on the upper respiratory tract. Paediatric respiratory reviews 18, 33–38 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zariwala M. A., Knowles M. R. & Leigh M. W. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. In GeneReviews(R) (eds R. A. Pagon, et al.) (Seattle (WA); 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Fretzayas A. & Moustaki M. Clinical spectrum of primary ciliary dyskinesia in childhood. World journal of clinical pediatrics 5, 57–62 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M., Milian L., Armengot M. & Carda C. Gene mutations in primary ciliary dyskinesia related to otitis media. Current allergy and asthma reports 14, 420 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruliere-Escabasse V. et al. Otologic features in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Archives of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery 136, 1121–1126 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer J. U. et al. ENT manifestations in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: prevalence and significance of otorhinolaryngologic co-morbidities. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268, 383–388 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D. J. Functional morphology of the lining membrane of the middle ear and Eustachian tube: an overview. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 83, Suppl 11, 15–26 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D. J. Functional morphology of the mucosa of the middle ear and Eustachian tube. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 85, 36–43 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Morphology and ciliary motion of mucosa in the Eustachian tube of neonatal and adult gerbils. PLoS One 9, e99840 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. & Lim D. J. Development of the mucociliary system in the eustachian tube and middle ear: murine model. Yonsei Med J 33, 64–71 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H. & Tucker A. S. Dual origin of the epithelium of the mammalian middle ear. Science 339, 1453–1456 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthwal N. & Thompson H. The development of the mammalian outer and middle ear. Journal of anatomy 228, 217–232 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete D. M. & Noden D. M. Developmental biology. A transition in the middle ear. Science 339, 1396–1397 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirao B. et al. Coupling between hydrodynamic forces and planar cell polarity orients mammalian motile cilia. Nat Cell Biol 12, 341–350 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunimoto K. et al. Coordinated ciliary beating requires Odf2-mediated polarization of basal bodies via basal feet. Cell 148, 189–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. F. & Kintner C. Cilia orientation and the fluid mechanics of development. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20, 48–52 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier A. & Azimzadeh J. Multiciliated Cells in Animals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B., Jacobs R., Li J., Chien S. & Kintner C. A positive feedback mechanism governs the polarity and motion of motile cilia. Nature 447, 97–101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford J. B. Planar cell polarity signaling, cilia and polarized ciliary beating. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22, 597–604 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladar E. K. & Axelrod J. D. Dishevelled links basal body docking and orientation in ciliated epithelial cells. Trends Cell Biol 18, 517–520 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladar E. K., Lee Y. L., Stearns T. & Axelrod J. D. Observing planar cell polarity in multiciliated mouse airway epithelial cells. Methods Cell Biol 127, 37–54 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota Y. et al. Planar polarity of multiciliated ependymal cells involves the anterior migration of basal bodies regulated by non-muscle myosin II. Development 137, 3037–3046 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata S. et al. Loss of Dishevelleds disrupts planar polarity in ependymal motile cilia and results in hydrocephalus. Neuron 83, 558–571 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying G. et al. Centrin 2 is required for mouse olfactory ciliary trafficking and development of ependymal cilia planar polarity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 34, 6377–6388 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D. T. et al. Zebrafish models of idiopathic scoliosis link cerebrospinal fluid flow defects to spine curvature. Science 352, 1341–1344 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B. et al. The PCP pathway instructs the planar orientation of ciliated cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Curr Biol 19, 924–929 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momose T., Kraus Y. & Houliston E. A conserved function for Strabismus in establishing planar cell polarity in the ciliated ectoderm during cnidarian larval development. Development 139, 4374–4382 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw W. Y. & Devenport D. Planar cell polarity: global inputs establishing cellular asymmetry. Curr Opin Cell Biol (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A. J. et al. Disruption of Bardet-Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature genetics 37, 1135–1140 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. et al. Ciliary proteins link basal body polarization to planar cell polarity regulation. Nature genetics 40, 69–77 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G. 3rd & Reiter J. F. A primer on the mouse basal body. Cilia 5, 17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegg M. et al. Flattop regulates basal body docking and positioning in mono- and multiciliated cells. eLife 3 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanos B. E. et al. Centriole distal appendages promote membrane docking, leading to cilia initiation. Genes & development 27, 163–168 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musah S., Chen J. & Hoyle G. W. Repair of tracheal epithelium by basal cells after chlorine-induced injury. Respir Res 13, 107 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole B. B. et al. Tracheal Basal cells: a facultative progenitor cell pool. The American journal of pathology 177, 362–376 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock J. R. et al. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 12771–12775 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch K. G. et al. A subset of mouse tracheal epithelial basal cells generates large colonies in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286, L631–642 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G. & Fuller M. T. Monoclonal antibodies specific for an acetylated form of alpha-tubulin recognize the antigen in cilia and flagella from a variety of organisms. The Journal of cell biology 101, 2085–2094 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary T., Larkins C. E. & Anderson K. V. The graded response to Sonic Hedgehog depends on cilia architecture. Developmental cell 12, 767–778 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegan P. S., Ostertag E., Geurts A. M. & Mooseker M. S. Myosin Id is required for planar cell polarity in ciliated tracheal and ependymal epithelial cells. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 72, 503–516 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempeneers C., Seaton C. & Chilvers M. A. Variation of ciliary beat pattern in 3 different beating planes in healthy subjects. Chest (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liote H., Zahm J. M., Pierrot D. & Puchelle E. Role of mucus and cilia in nasal mucociliary clearance in healthy subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 140, 132–136 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee C. S. et al. Ciliary beat frequency in cultured human nasal epithelial cells. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110, 1011–1016 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipor I., Palmer J. N., Cohen A. S. & Cohen N. A. Quantification of ciliary beat frequency in sinonasal epithelial cells using differential interference contrast microscopy and high-speed digital video imaging. Am J Rhinol 20, 124–127 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaari J. et al. Regional analysis of sinonasal ciliary beat frequency. Am J Rhinol 20, 150–154 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. F. Basal bodies platforms for building cilia. Current topics in developmental biology 85, 1–22 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovina A., Superina S., Voskas D. & Ciruna B. Vangl2 directs the posterior tilting and asymmetric localization of motile primary cilia. Nat Cell Biol 12, 407–412 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K. et al. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science 329, 1337–1340 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibar Z. et al. Ltap, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila Strabismus/Van Gogh, is altered in the mouse neural tube mutant Loop-tail. Nature genetics 28, 251–255 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian D. et al. Wnt5a functions in planar cell polarity regulation in mice. Dev Biol 306, 121–133 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nature genetics 37, 980–985 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montcouquiol M. et al. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature 423, 173–177 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D. J., Paparella M. M. & Kimura R. S. Ultrastructure of the eustachian tube and middle ear mucosa in the guinea pig. Acta Otolaryngol 63, 425–444 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussl B. & Lim D. J. Secretory cells in the middle ear mucosa of the guinea pig. Cytochemical and ultrastructural study. Arch Otolaryngol 89, 691–699 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indra A. K. et al. Temporally-controlled site-specific mutagenesis in the basal layer of the epidermis: comparison of the recombinase activity of the tamoxifen-inducible Cre-ER(T) and Cre-ER(T2) recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 4324–4327 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M. D., Tasic B., Miyamichi K., Li L. & Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593–605 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Shao C., Song Y., Bai C. & He L. Clinical analysis of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia in mainland China. The clinical respiratory journal (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald D. A. & Shapiro A. J. When to suspect primary ciliary dyskinesia in children. Paediatric respiratory reviews 18, 3–7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie P., Fitzgerald D. A., Jaffe A., Birman C. S. & Morgan L. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: overlooked and undertreated in children. Journal of paediatrics and child health 50, 952–958 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagel S. D., Davis S. D., Campisi P. & Dell S. D. Update of respiratory tract disease in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 8, 438–443 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen T. N., Alanin M. C., von Buchwald C. & Nielsen L. H. A longitudinal evaluation of hearing and ventilation tube insertion in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 89, 164–168 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F. et al. Otitis media in a mouse model for Down syndrome. International journal of experimental pathology 90, 480–488 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C. et al. Otitis media in a new mouse model for CHARGE syndrome with a deletion in the Chd7 gene. PLoS One 7, e34944 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarts J. D. et al. Panel 2: Eustachian tube, middle ear, and mastoid--anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology, and pathogenesis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 148, E26–36 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs J. C. & Tucker A. S. Development and Integration of the Ear. Current topics in developmental biology 115, 213–232 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. J. Structure and function of the mammalian middle ear. II: Inferring function from structure. Journal of anatomy 228, 300–312 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. S., Ben-Shahar Y., Moninger T. O., Kline J. N. & Welsh M. J. Motile cilia of human airway epithelia are chemosensory. Science 325, 1131–1134 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey R. M., Lee R. J. & Cohen N. A. Taste Receptors in Upper Airway Immunity. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 79, 91–102 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. J. & Cohen N. A. Bitter and sweet taste receptors in the respiratory epithelium in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 92, 1235–1244 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coren M. E., Meeks M., Morrison I., Buchdahl R. M. & Bush A. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: age at diagnosis and symptom history. Acta Paediatr 91, 667–669 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlink E., Hogg C., Carr S. B. & Bush A. Clinical phenotype and current diagnostic criteria for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Expert Rev Respir Med, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaretto F. et al. Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia by a Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Panel: Molecular and Clinical Findings in Italian Patients. J Mol Diagn 18, 912–922 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon-Heszele M. F., Ren D., Reynolds A. B., Chi F. & Chen P. Regulation of cochlear convergent extension by the vertebrate planar cell polarity pathway is dependent on p120-catenin. Development 139, 968–978 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs B. C. et al. Prickle1 mutation causes planar cell polarity and directional cell migration defects associated with cardiac outflow tract anomalies and other structural birth defects. Biol Open 5, 323–335 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K. U., Reynolds S. D., Watkins S., Fuchs E. & Stripp B. R. In vivo differentiation potential of tracheal basal cells: evidence for multipotent and unipotent subpopulations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286, L643–649 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R. B. et al. p63 regulates olfactory stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Neuron 72, 748–759 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.