Abstract

Nanosecond ligand exchange dynamics at metal sites within proteins is essential in catalysis, metal ion transport, and regulatory metallobiochemistry. Herein we present direct observation of the exchange dynamics of water at a Cd2+ binding site within two de novo designed metalloprotein constructs using 111mCd perturbed angular correlation (PAC) of γ-rays and 113Cd NMR spectroscopy. The residence time of the Cd2+-bound water molecule is tens of nanoseconds at 20 °C in both proteins. This constitutes the first direct experimental observation of the residence time of Cd2+ coordinated water in any system, including the simple aqua ion. A Leu to Ala amino acid substitution ~10 Å from the Cd2+ site affects both the equilibrium constant and the residence time of water, while, surprisingly, the metal site structure, as probed by PAC spectroscopy, remains essentially unaltered. This implies that remote mutations may affect metal site dynamics, even when structure is conserved.

Interactions of water molecules with proteins and nucleic acids play a critical role in biomolecular structure, function, and dynamics.1–6 In particular, significant effort has been expended toward understanding the dynamics of water molecules interacting with the surface and interior organic constituents of proteins.7–14 Metalloproteins constitute about one-third of all known proteins,15 and ligand exchange reactions at the metal sites involving exogenous ligands, e.g. water molecules, represent the key elementary steps in metalloenzyme catalyzed reactions, regulatory biochemical processes, and transport of metal ions across cell membranes. By approaching the issue from the viewpoint of the chemistry of metal ions in aqueous solution, the Eigen–Wilkins mechanism highlights the rate of water exchange in the first coordination sphere as a central property, affecting the mechanism and kinetics of formation of metal ion complexes.16–19 Although significant progress has been made since these groundbreaking insights, it is interesting to note that all estimates of water exchange kinetics for the divalent group 12 metal ions (Zn2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+) rely on ligand substitution experiments; i.e. no direct experimental determination has been reported, except for an estimate of the Zn2+ coordinated water proton residence time of 0.1–5 ns in 2.58 molal Zn(ClO4)2 solution using incoherent quasi-elastic neutron scattering (IQENS).20 Several biologically relevant metal ions are expected to display nanosecond ligand exchange dynamics,17,18 but spectroscopic characterization of dynamics on the nanosecond to microsecond time scale6,9,21–23 is not trivial. For diamagnetic metal ions, which are often critically important for Lewis Acid assisted catalysis, the paucity of experimental data is due to the fact that ligand exchange dynamics on the relevant nanosecond time scales is inaccessible by most experimental techniques, although, in an elegant NMR study by Denisov and Halle, the residence time of a Ca2+-bound water molecule in Calbindin D9k was determined within a broad range of 5 ns–7 µs.22 Clearly then, an experimental underpinning of water dynamics at protein metal sites is essential.

De novo designed peptides provide simplified biological constructs where metal binding sites can be incorporated by careful design, and the factors controlling the structural and dynamical properties of the ligand(s) bound to the metal ion can be assessed.24 The TRI family of peptides (general sequence Ac-G-(LaKbAcLdEeEfKg)4-G-NH2) that self-assemble into parallel three-stranded α-helical coiled coils (3SCC) is among the most extensively studied systems with abundant spectroscopic, structural, and kinetic data available.25–30 Substitution of Leu residues with soft, metal coordinating Cys residues renders preorganized homoleptic thiol-rich metal binding sites at the interior of the coiled coils suitable for binding a variety of heavy metals including Cd2+.25–32 Herein, we report direct determination of exchange rates of a water molecule bound to Cd2+ ion within the two 3SCC peptides TRIL16C and TRIL16CL23A (Figure 1).

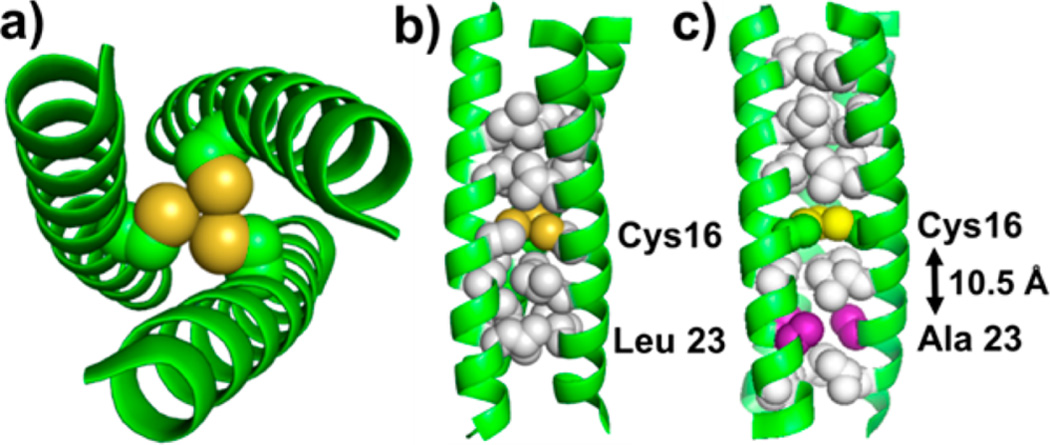

Figure 1.

Models of 3SCC used in this study. (a) N → C terminus view of TRIL16C showing the three Cys residues at the metal site. (b) TRIL16C oriented perpendicular to the helical axis. Cys16 and the closest Leu layers are shown explicitly. (c) TRIL16CL23A with indication of the Leu23Ala substitution (purple). Protein backbone is shown as green cartoon, thiol groups of Cys as yellow spheres, and Leu layers as white spheres. The model was generated using a 3SCC (Coil Ser) PDB ID 3H5G30 and PyMol.33

Previous work on Cd(TRIL16C)3− showed a single 113Cd NMR resonance at 625 ppm, yet the 111mCd PAC data indicated the presence of two coexisting Cd2+ complexes: a pseudotetrahedral CdS3O (O = exogenous water) species and a trigonal planar CdS3 species,34 which was supported by quantum chemical calculations.35,36 From these analyses, it was concluded that the two species CdS3O and CdS3 are in rapid chemical exchange on the NMR time scale (ms), but in slow exchange on the PAC time scale (ns). The water exchange reaction is illustrated in Figure 2, and a temperature series of PAC data is shown in Figure 3.

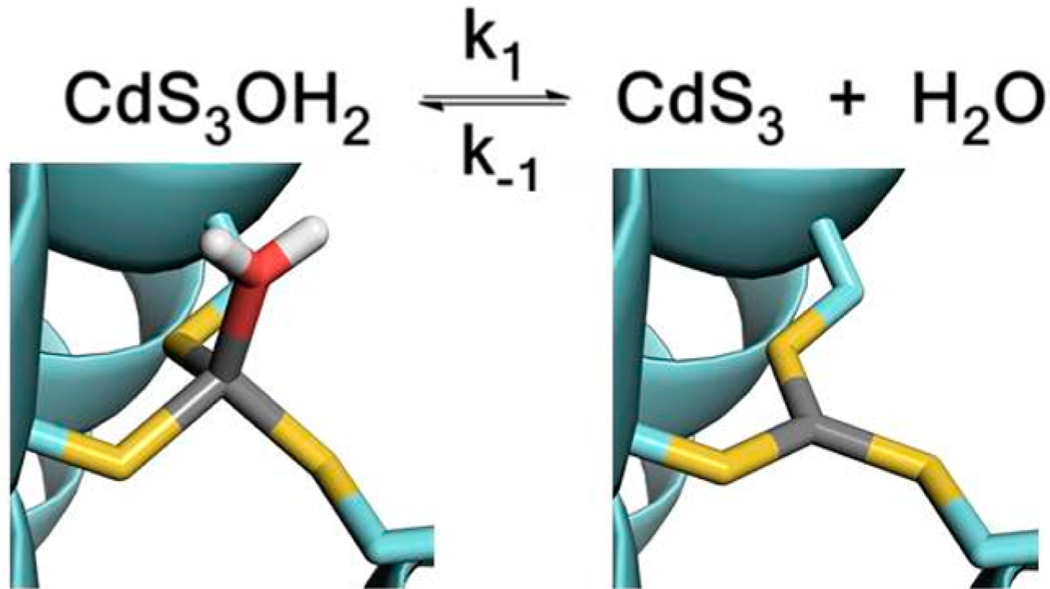

Figure 2.

Schematic of the water exchange reaction. The peptide backbone is shown in pale blue, Cys in pale blue and yellow sticks, Cd2+ in gray, and water in red and white. The Cd2+ binding sites were modeled based on the structure of CSL9C (PDB ID 3LJM).27

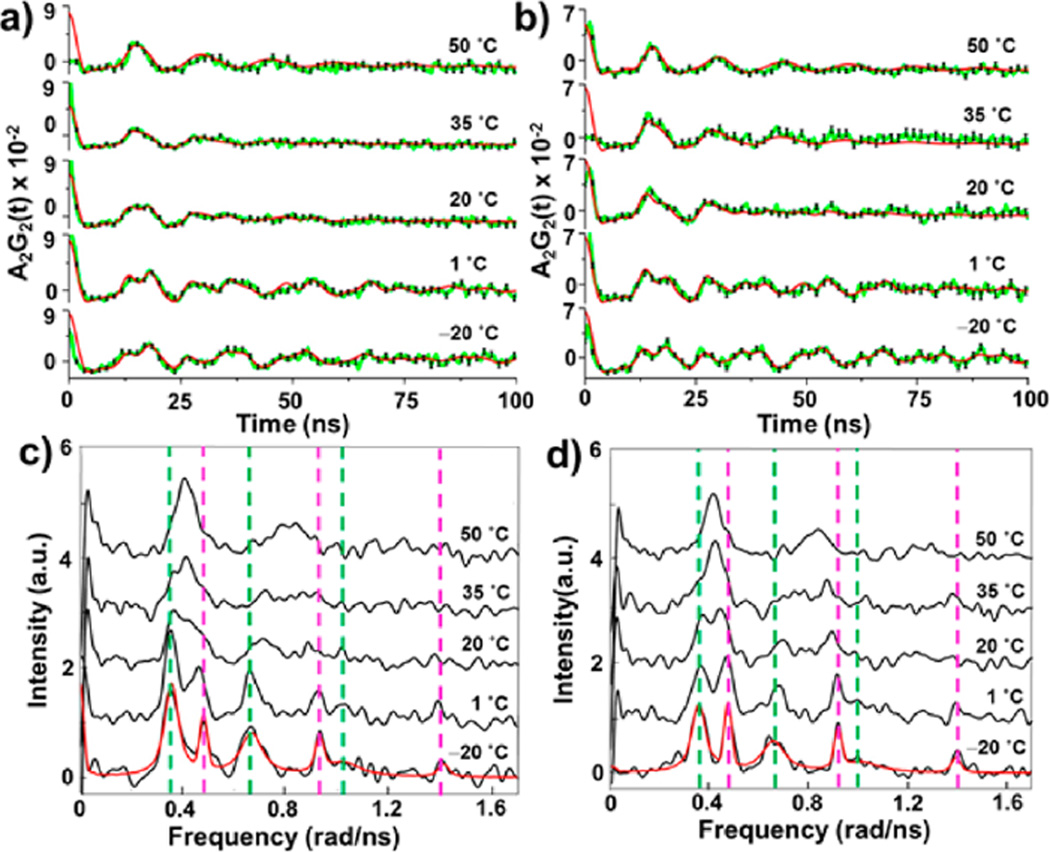

Figure 3.

111mCd PAC spectra at different temperatures for TRIL16C (a) and TRIL16CL23A (b). Experimental data are shown as green lines connecting data points, fits as red lines, and error bars as black lines. Fourier transformed 111mCd PAC spectra for TRIL16C (c) and TRIL16CL23A (d) at different temperatures. Experimental data are shown as black lines. Fits to the data at −20 °C for both peptides are shown as red lines. Each coordination geometry gives rise to one NQI, appearing as three peaks in the spectra. Representative signals from the CdS3O and CdS3 species are indicated with green and magenta vertical lines, respectively.

The PAC spectra at −20 °C indicate the expected presence of two nuclear quadrupole interactions (NQIs), reflecting the coexistence of CdS3O and CdS3 species, and that the water exchange is taking place in the slow exchange regime with ~100 ns or a longer lifetime of the two species. The PAC signals for both CdS3 and CdS3O are resolved at −20 °C and, therefore, used to determine the static NQI parameters for the two species for both peptides (Table S1).

The two sets of signals reflecting CdS3O and CdS3 species are discernible up to 1 °C for both peptides with the onset of some extent of line broadening, indicating that the water exchange is occurring in the slow to intermediate exchange regime. At 20 °C, the two signals begin to merge into a broad signal, and at 35 °C they coalesce to a single broad signal with large line widths, indicating water exchange on the intermediate time scale. With a further increase in temperature to 50 °C one signal with a smaller line width is observed, indicating that the water exchange is approaching the fast exchange regime. Another qualitative observation, which indirectly demonstrates changes in the water residence time upon the L23A substitution, is the following: The amplitude, A, of signals in PAC spectroscopy directly reflects the species population, and the amplitude of the CdS3 signal increases from the spectrum (recorded at −20 °C and at 1 °C) for the TRIL16C peptide to that recorded for TRIL16CL23A, and vice versa for the CdS3O signal (Figure 3). That is, the equilibrium constant, K, for water dissociation (Figure 2) is increased upon L23A substitution. We hypothesize that removal of steric bulk by replacing the Leu23 with Ala stabilizes the CdS3 structure in TRIL16CL23A as compared to TRIL16C. While it is possible to stabilize the CdS3 or CdS3O metal site structure selectively by altering the first or second coordination sphere by steric control of the hydrophobes ~5 Å from the metal binding site in other TRI peptide derivatives,37,38 our results here show that even the Leu23Ala substitution ~10 Å away affects the relative population of the CdS3 or CdS3O species. More importantly in the context of the current work, the increase of the equilibrium constant, K, upon the L23A substitution demonstrates that the rates (k1 and k−1) must also change, in a manner so as to increase K = k1/k−1. The quantitative assessment of the rates based on the PAC data is addressed in the following section.

The data sets at temperatures 1 to 50 °C were analyzed using the two NQIs derived at −20 °C and simulations modeling the effect of exchange dynamics on the PAC spectra, with only the lifetimes of the CdS3 and CdS3O species as variables (Table 1). The details of the data analysis may be found in the Supporting Information and Tables S1–S4. The remarkable agreement of the fits with the 111mCd PAC experimental data (Figure 3 a,b) indicates that water exchange dynamics is indeed the origin of the observed changes of the spectroscopic signal with temperature. This is the first unambiguous demonstration of exchange dynamics at a biomolecular metal site using PAC spectroscopy, the first precise determination of nanosecond metal site dynamics in a biomolecule for any diamagnetic metal ion, and the first direct observation of water exchange dynamics for any of the divalent group 12 metal ions in general,16–18 except for the above-mentioned IQENS experiments.20

Table 1.

Lifetimes of the CdS3O (τ1) and CdS3 (τ−1) Species Derived from the 111mCd PAC Dataa

| TRIL16C | TRIL16CL23A | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t [°C] | τ1 [ns] | τ−1 [ns] | τ1 [ns] | τ−1 [ns] |

| 1 | 55 | 40 | 44 | 45 |

| 20 | 30 | 23 | 25 | 29 |

| 35 | 17 | 16 | 13 | 15 |

| 50 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 7 |

The statistical standard deviation of the lifetimes is ~1 ns, but does not include errors due to assumptions in the model (see the SI).

The residence time of the water molecule bound to Cd2+ is 30 ns for TRIL16C and 25 ns for TRIL16CL23A at 20 °C Table 1), as derived from the PAC data. A broad range of rate constants for ligand binding to Cd2+ ion in solution has been observed (105 – 5 × 109 M−1 s−1),39 possibly indicating that the rate depends on the type of ligand as well as the water exchange rate. In the protein, the water exchange clearly occurs via a dissociative mechanism, because the CdS3 species is explicitly observed. This is contrary to the Cd2+ aqua ion, for which a negative volume of activation has been determined for bipyridine binding, indicating an associative exchange mechanism.40 These observations indicate that the mechanism and kinetics of water association with and dissociation from the metal site in proteins may be fine-tuned by using suitably designed protein scaffolds. The fine-tuning may be achieved directly by limiting the ingress and egress of water through the protein matrix, or indirectly by changing the metal site spectator ligands (in this case thiolates) or the coordination number. However, here we demonstrate that even more subtle changes in the amino acid sequence ~10 Å away from the metal site can also affect the water exchange rate, because the Leu23Ala substitution in TRIL16CL23A causes a systematic decrease of the residence time (τ1) of the metal ion bound water molecule, compared to TRIL16C. The lifetime of the species without coordinating water (τ−1) is less systematically affected (Table 1). These results suggest that either the CdS3O structure is destabilized relative to the CdS3 structure upon the L23A substitution or the transition state of the water dissociation reaction is stabilized, or a combination of both. The fact that the Leu23Ala substitution also shifts the equilibrium toward the CdS3 structure (vide supra) provides further support of the destabilization of the CdS3O structure in TRIL16CL23A. Thus, even remote mutations can affect the dynamics at metal sites in proteins, indicating that the first and second coordination sphere are not the only factors that affect the physical and chemical properties.

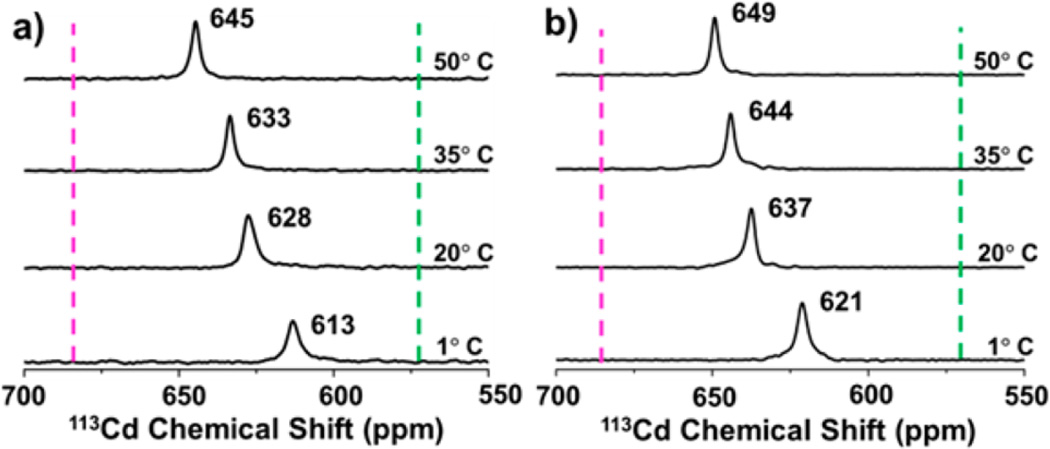

We next tested whether 113Cd NMR spectroscopy support the interpretation of the PAC data in terms of changes in equilibrium population of CdS3 and CdS3O species as a function of temperature. Single resonances are observed for both peptides at all temperatures (Figure 4), indicating that the CdS3O and CdS3 species are in fast exchange on the NMR time scale.

Figure 4.

113Cd NMR spectra of TRIL16C (a) and TRIL16CL23A (b) with indication of representative chemical shifts observed for pure CdS3O (green vertical lines) and CdS3 (magenta vertical lines) species.41.

The reference chemical shifts for pure CdS3 and CdS3O species are 684 ppm for TRIL16Pen (CdS3) and 574 ppm for TRIL12AL16C (CdS3O), respectively.41 The relative population of the two species determined by PAC spectroscopy then allows for prediction of the chemical shift for the two species in rapid exchange. At 1 °C the PAC data display a relative population of 34% (CdS3) and 66% (CdS3O) for TRIL16C and 41% (CdS3) and 59% (CdS3O) for TRIL16CL23A, respectively (Table S1). Thus, the predicted 113Cd NMR resonances are 611 and 619 ppm for TRIL16C and TRIL16CL23A, respectively, in excellent agreement with the experimentally observed chemical shifts of 613 and 621 ppm (Figure 4). Therefore, the 113Cd NMR data provide an independent test of the interpretation of the PAC data in terms of water exchange dynamics. A more downfield chemical shift is observed for both peptides with increasing temperature, reflecting a change in the population of the two species, shifting the equilibrium toward the CdS3 species. The same trend is observed in the PAC spectroscopic data (Table 1), further corroborating the interpretation. That is, both the NMR and PAC data indicate an increase of the equilibrium constant, K, for the water dissociation reaction (Figure 2) with increasing temperature. This implies that dissociation of water from the metal site is an exothermic process, as expected.

111mCd PAC spectroscopy is very sensitive to structural changes at the probe site.36 Thus, it is noteworthy that the static NQI parameters for both the CdS3O and the CdS3 species are highly similar in TRIL16C and TRIL16CL23A (Table S1). Accordingly, the PAC data indicate that the metal site structure is essentially unchanged by the Leu23Ala amino acid substitution, yet both the equilibrium constant and the kinetics of water exchange are altered. This observation implies that even when structure is conserved, the thermodynamics and kinetics of processes at metal sites, and therefore potentially also the function, may change. This elucidation of remote site control of water exchange adds to the comprehensive literature indicating the importance of dynamics for protein function.42 Moreover, our findings suggest a potentially very important caveat when interpreting data on site directed mutagenesis of natural metalloproteins. While the overall structure may appear unaltered, the water exchange dynamics could be perturbed even by changes several residues away from the metal center. Similarly, remote mutations have been shown to perturb the active site dynamics and catalytic properties of other proteins.43,44

By using simplified, designed proteins and a spectroscopic technique of the appropriate time scale, we have demonstrated that ns ligand exchange rates can be determined directly for water binding to metals in well-defined α-helical coiled coils and that these exchange reactions may be controlled even by mutations several residues from the metal center. The methodology presented here is limited mainly by the relatively narrow selection of PAC isotopes.36,45

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

L.H. thanks The Danish Council for Independent Research | Natural Sciences, and the Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation, Denmark, for the NICE grant. V.L.P. thanks the National Institutes of Health for financial support of this research (ES012236).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

- Materials and Methods and details of data analysis (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levitt M, Park H. Structure. 1993;1:223–226. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hummer G. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:906–907. doi: 10.1038/nchem.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler D. Nature. 2005;437:640–647. doi: 10.1038/nature04162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qvist J, Persson E, Mattea C, Halle B. Faraday Discuss. 2009;141:131–144. doi: 10.1039/b806194g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denisov VP, Peters J, Horlein HD, Halle B. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nsb0696-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson E, Halle B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1774–1787. doi: 10.1021/ja0775873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellissent-Funel M-C, Hassanali A, Havenith M, Henchman R, Pohl P, Sterpone F, van der Spoel D, Xu Y, Garcia AE. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:7673–7697. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King JT, Arthur EJ, Brooks CL, III, Kubarych KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:188–194. doi: 10.1021/ja407858c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross MR, White AM, Yu F, King JT, Pecoraro VL, Kubarych KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10164–10176. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang K-Y, Kingsley CN, Sheil R, Cheng C-Y, Bierma JC, Roskamp KW, Khago D, Martin RW, Han S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5392–5402. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nucci NV, Pometun MS, Wand AJ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:245–249. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia M, Yang J, Qin Y, Wang D, Pan H, Wang L, Xu J, Zhong D. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:5100–5105. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood K, Frölich A, Paciaroni A, Moulin M, Härtlein M, Zaccai G, Tobias DJ, Weik M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4586–4587. doi: 10.1021/ja710526r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal SK, Peon J, Zewail AH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1763–1768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042697899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreini C, Bertini I, Cavallaro G, Holliday G, Thornton J. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:1205–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richens DT. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1961–2002. doi: 10.1021/cr030705u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helm L, Merbach AE. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1923–1960. doi: 10.1021/cr030726o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helm L, Nicolle GM, Merbach AE. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2005;57:327. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eigen M, Wilkins RG. Adv. Chem. Ser. 1965;49:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmon P, Bellissent-Funel M-C, Herdman G. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 1990;2:4297. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen DF, Westler WM, Kunze MBA, Markley JL, Weinhold F, Led JJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4670–4682. doi: 10.1021/ja209348p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denisov VP, Halle B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:8456–8465. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zang C, Stevens JA, Link JJ, Guo L, Wang L, Zhong D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2846–2852. doi: 10.1021/ja8057293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh D, Pecoraro VL. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:7902–7915. doi: 10.1021/ic048939z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu F, Cangelosi VM, Zastrow ML, Tegoni M, Plegaria JS, Tebo AG, Mocny CS, Ruckthong L, Qayyum H, Pecoraro VL. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:3495–3578. doi: 10.1021/cr400458x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Touw DS, Nordman CE, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:11969–11974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701979104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakraborty S, Touw DS, Peacock AFA, Stuckey J, Pecoraro VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13240. doi: 10.1021/ja101812c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakraborty S, Iranzo O, Zuiderweg ERP, Pecoraro VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6191–6203. doi: 10.1021/ja210510g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iranzo O, Chakraborty S, Hemmingsen L, Pecoraro VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:239–251. doi: 10.1021/ja104433n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peacock AFA, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7371–7374. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruckthong L, Zastrow ML, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:11979–11988. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zastrow ML, Peacock AFA, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Nat. Chem. 2011;4:118–123. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Palo Alto, California, USA: DeLano Scientific; 2005. http://www.pymol.org. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matzapetakis M, Farrer BT, Weng T-C, Hemmingsen L, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8042–8054. doi: 10.1021/ja017520u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemmingsen L, Stachura M, Thulstrup PW, Christensen NJ, Johnston K. Hyperfine Interact. 2010;197:255–267. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hemmingsen L, Sas KN, Danielsen E. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:4027–4062. doi: 10.1021/cr030030v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peacock AFA, Hemmingsen L, Pecoraro VL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:16566–16571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806792105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee K-H, Cabello C, Hemmingsen L, Marsh ENG, Pecoraro VL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:2864–2868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkins RG. Kinetics and Mechanism of Reactions of Transition Metal Complexes. 2nd. Weinheim, FRG: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ducommun Y, Laurenczy G, Merbach AE. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:1148–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danielsen E, Jorgensen L, Sestoft P. Hyperfine Interact. 2002;142:607–626. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shukla D, Hernández CX, Weber JK, Pande VS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:414–422. doi: 10.1021/ar5002999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacewicz A, Trzemecka A, Guja KE, Plochocka D, Yakubovskaya E, Bebenek A, Garcia-Diaz M. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saen-Oon S, Ghanem M, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Biophys. J. 2008;94:4078–4088. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zacate MO, Favrot A, Collins GS. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:225901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.225901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.