Abstract

The association between the quality of people’s close relationships and their physical health is well-established. But from a psychological perspective, how do close relationships impact physical health? This article summarizes recent work seeking to identify the relationship processes, psychological mediators and moderators of the links between close relationships and health, with an emphasis on studies of married and cohabitating couples. We begin with a brief review of a recent meta-analysis of the links between marital quality and health. We then describe our strength and strain model of marriage and health, homing in on one process—partner responsiveness—and one moderator—adult attachment style—to illustrate ways in which basic relationship science can inform our understanding of how relationships impact physical health. We conclude with a brief discussion of promising directions in the study of close relationships and health.

Keywords: marriage, health, marital quality, relationships, cortisol

There is a long tradition of studies investigating the links between social relationships and health. This area of research received a shot in the arm with House, Landis and Umberson’s article “Social Relationships and Health,” which appeared in Science in 1988. That paper used several epidemiological studies to illustrate a consistent link between stronger social ties and greater longevity. The authors concluded that “social relationships, or the relative lack thereof, constitute a major risk factor for health—rivaling the effects of well-established risk factors such as cigarette smoking, blood pressure, blood lipids, obesity, and physical activity” (p. 541). That claim was definitively supported in a meta-analysis of over 300,000 participants across 148 studies, indicating a 50% increased likelihood of survival for people with stronger social bonds (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Thus, the question of whether social relationships impact physical health has been answered with a resounding “yes.” But from a psychological perspective, how do social relationships impact physical health?

A logical place that researchers have looked for answers to this “how” question is social psychology. Over the past three decades, relationship scientists have made numerous breakthroughs in identifying factors that lead to intimate, satisfying and committed relationships. At the same time, there has been considerable theoretical and empirical work on the mechanisms linking social relationships to health (Cohen, 1988; Lewis & Rook, 1999; Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009; Pietromonaco, Uchino, & Dunkel Schetter, 2013; Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996). However, much of the existing theoretical work is based primarily on broad social networks, including family, friends, and acquaintances. Yet research in social psychology suggests the possibility that our closest relationships—those with a spouse or long-term romantic partner—have particularly potent effects on health. Moreover, a growing literature on the development of close relationships provides us with a blueprint for addressing the psychological processes by which relationships are linked to physical health.

The goal of this article is to provide a concise summary of the work that we (and others) have been doing to identify the relationship processes, psychological mediators and moderators of the links between close relationships and health, with a particular focus on long-term romantic relationships. We begin with a brief review of a recent meta-analysis of the links between marital quality and health. We then describe our strength and strain model of marriage and health, homing in on one process—partner responsiveness—and one potentially important moderator—adult attachment style—to illustrate ways in which basic relationship science can inform our understanding of how relationships impact physical health. We conclude with a brief discussion of promising directions in the study of close relationships and health.

Meta-Analysis of Marital Quality and Health

A recent meta-analysis showed robust associations between the quality of people’s marriages and their physical health (Robles, Slatcher, Trombello, & McGinn, 2014), including lower risk of mortality. Although the reported effect sizes generally would be considered small by conventional psychology standards (r’s between .07 and .21, depending on the type of health outcome), they are similar to the effect sizes of typical behavior intervention targets (e.g., increasing fruit and vegetable intake, decreasing sedentary activity) for improving health.

Perhaps most surprising about our meta-analysis was how little we could glean about the specific aspects of marriage that matter most for physical health—positive aspects (e.g., intimacy, understanding), negative aspects (e.g., conflict, hostility), or both. Further, almost no studies examined moderators of the links between marital quality and health. Below, we describe our theoretical model, which provides a starting point for investigating the mediators and moderators of marriage-health links.

The Strength and Strain Model

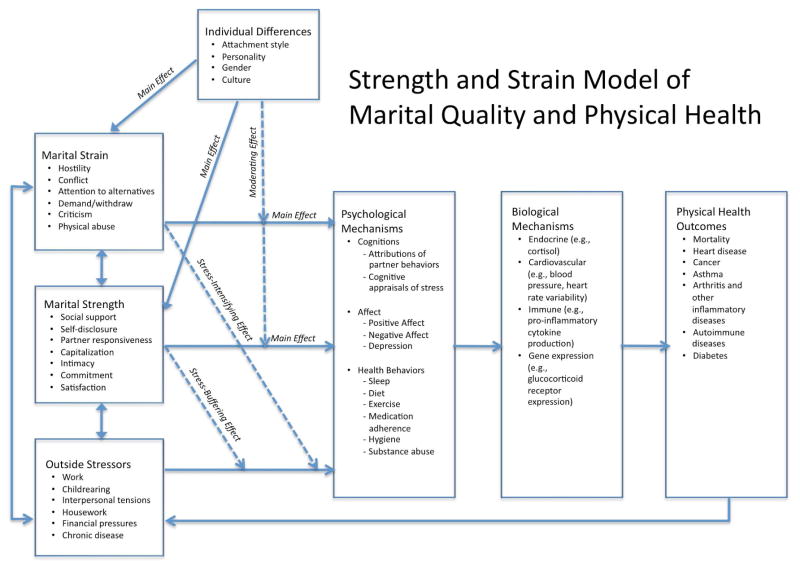

The theoretical model that guides our work (shown in Figure 1) illustrates the hypothesized effects of marital quality on physical health (originally described in Slatcher, 2010 but refined here). In this model, marital strengths (positive aspects of marriage) and marital strains (negative aspects of marriage) both have main effects on health, as well as moderating effects on links between outside stressors (e.g., work stress) and health. Our model shares many common elements with earlier models of marriage and health (e.g., Burman & Margolin, 1992; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001), models of stress and marriage (e.g., Karney & Bradbury, 1995), and models of social support and health (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Uchino, et al., 1996), with a key difference that we use the term “strength” over the more widely used “support.” The term strength is meant to capture the range of positive processes in relationships (e.g., intimacy, capitalization, support) that have increasingly been the focus of relationship scientists (Reis & Gable, 2003). It is this greater emphasis on positive relationship processes (beyond just social support in stressful contexts) in our model that distinguishes it from most prior models of marriage and health. Although both marital strain and marital strength are proposed to moderate the effects of outside stressors on health, only marital strength should buffer, or protect, against the negative health effects of stress – whereas marital strain should intensify, or exacerbate those effects. This model also presupposes that individual differences, including gender, personality traits, and attachment style should moderate the effects of marital quality on health. However, as indicated by our recent meta-analysis (Robles, et al., 2014), almost no studies have tested moderators. The field is thus ripe for consideration of these factors. Below, we describe a process (partner responsiveness) and a moderator (adult attachment style) as examples of key parts of the strength and strain model.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model illustrating how marital quality influences physical health directly via psychological and biological pathways and indirectly via its moderating influence on the effects of outside stressors (either stress-intensifying or stress-buffering). Also included in the model are individual difference factors, which can moderate the health effects of relationship processes or, alternatively, can directly impact relationship processes (main effects).

Partner Responsiveness, Attachment, and Health

Partner responsiveness refers to the extent to which individuals are caring, understanding, and validating of their partners (Reis, 2013). Numerous influential relationship theories (attachment theory, interdependence theory, social support theory) ascribe a central role to partner responsiveness in linking relationships to health and well-being. Among these, attachment theory is probably the one that most prominently features responsiveness as the core aspect of close relationships “from the cradle to the grave” (Bowlby, 1988). Perceiving partners—the prototypical attachment figures in adulthood (Hazan & Shaver, 1987)—as responsive brings a sustained sense of security, which in turn is thought to promote health and well-being in the long-run. Failures to perceive partners as responsive, on the other hand, leads to two types of attachment insecurities. Attachment anxiety (characterized by worries of rejection and abandonment) is linked to inconsistent partner responsiveness where the partner is sometimes responsive and sometimes not, or responsive only to persistent distress signals and excessive reassurance seeking (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Attachment avoidance (characterized by discomfort with depending on relationship partners) is linked to consistent partner unavailability and unresponsiveness (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Both attachment insecurities are thought to increase the likelihood of later physical health problems.

Recent work investigating attachment-related health effects using diverse methodologies (e.g., experiments, longitudinal follow-ups, daily experience designs) has shown that differences in partner responsiveness are likely to influence later health by way of regulating physiological responses to stress, promoting health behaviors, reducing pain, and moderating the effectiveness of social support.

Alteration of Stress Regulatory Systems

Prior developmental work showed that maternal responsiveness leads to changes in functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis (HPA), the body’s major stress-regulation system, and its hormonal product, cortisol during childhood (Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007). Is such a long-term fine-tuning of the HPA system possible in adulthood? If romantic partners are capable of inducing such long-term changes, then this would probably be one of the most critical pathways through which close relationships affect later health. Our research group investigated this question in a large sample of married and cohabiting adults in a 10-year longitudinal study. We found that partner responsiveness predicted a “healthier” diurnal cortisol profile (as indicated by steeper declines in daytime cortisol) a decade later (Slatcher, Selcuk, & Ong, 2015). This long-term association between responsiveness and diurnal cortisol was partially mediated by a psychological mechanism, namely negative affect, as suggested in Figure 1. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only evidence so far in humans suggesting the exciting possibility that adult romantic relationships may lead to long-term changes in the HPA axis, potentially resulting in beneficial changes in cortisol production and thus, physical health.

Immune Functioning

Our findings indicate that relationships with unresponsive partners may be linked to dysregulated cortisol profiles. This is particularly true for anxiously attached individuals, whose chronic worries about abandonment and intense signaling of distress to get partner support result in increased cortisol production in daily life (Jaremka, et al., 2013). Overproduction of cortisol, in turn, is associated with alterations in the immune system. Recent work has linked attachment anxiety with indicators of weaker immune functioning, including lower T-cell counts (involved in activating immune cells and responding to infections) (Jaremka, et al., 2013), higher levels of latent herpesvirus reactivation (Fagundes, et al., 2014), and exacerbated inflammatory response to cardiac surgery (Kidd, et al., 2014), suggesting that failures to perceive one’s partner as responsive may lead to impairments in the immune system.

Health Behaviors

The associations between partner responsiveness and health behaviors have not been studied extensively, but attachment theory can guide future investigations of relationship effects on health behaviors. An excellent example is research on adult sleep (Troxel, 2010). High quality sleep requires down-regulation of arousal and anxiety, which is precisely what partner responsiveness serves to alleviate. Recent data from our group indicates that partner responsiveness indirectly predicts increased subjective sleep quality and objective (actigraph-assessed) sleep efficiency through decreased anxious arousal (Selcuk, Stanton, Slatcher, & Ong, 2016). Corroborating these findings, both types of insecure attachment styles have also been linked to poorer sleep (Adams, Stoops, & Skomro, 2014).

Pain Regulation

Responsive interactions with partners result in the release of endogenous opioids, which not only instill a sense of security and contentment but also reduce feelings of pain (Machin & Dunbar, 2011). Indeed, one of the first studies on the health implications of partner responsiveness showed that greater partner responsiveness predicts lower knee pain three months after knee replacement surgery (Khan, et al., 2009). Conversely, failure to appraise partner behaviors as responsive, as in the case of those who are anxious or avoidantly attached, increases vulnerability to developing chronic pain (Meredith, Ownsworth, & Strong, 2008).

Moderation of Received Support

A counterintuitive research finding is that receiving support from loved ones is sometimes associated with poorer well-being (Bolger, Zuckerman, & Kessler, 2000) and physical health outcomes, including early mortality (Uchino, 2009). In a recent examination of partner responsiveness in moderating the association between partner support and physical health, we found that received partner support predicted a higher risk for all-cause mortality a decade later for individuals who perceived their partner as unresponsive (Selcuk & Ong, 2013). However, this paradoxical association disappeared for individuals who perceived their partner as responsive.

In sum, accumulating evidence has started to uncover a network of processes linking partner responsiveness to health. Importantly, studies also indicated that partner responsiveness has a discriminant role in predicting health-related biology, since the effects of responsiveness hold even after partialling out potential confounds, including other positive or negative aspects of relationships (Slatcher, et al., 2015), psychological symptoms (Selcuk & Ong, 2013; Slatcher, et al., 2015), personality traits and physical health indicators (e.g., chronic symptoms; Selcuk & Ong, 2013).

We should note that much of the work reviewed here focused on middle or older adults with established long-term relationships, when much of the protective health benefits are realized. Early-stage romantic relationships, which are more commonly studied in young adulthood, do not always demonstrate the typical characteristics of full-blown attachment bonds (e.g., partners being secure bases for each other; Zeifman & Hazan, 2008). We speculate that although perceptions of responsiveness in early-stage relationships would promote the development of attachment and intimacy, the effects on health are likely to be conferred over a much longer time period. Of course only future empirical work will tell whether and how the health effects of romantic relationships change with age and relationship development.

Moving Forward with Greater Interdisciplinary Integration

Although many relationship researchers (including ourselves) were influenced by developmental attachment theory, work on childhood and romantic attachment have progressed relatively separately from each other. Integration of these fields will help us better understand lifespan effects of relationships on health. Early life stress, particularly unresponsive caregiving, is associated with insecure attachment (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978), which in turn affects developing stress neurobiology and health (Loman & Gunnar, 2010). Growing evidence shows that these early effects extend well into adulthood (e.g., Taylor, Karlamangla, Friedman, & Seeman, 2011). Early caregiving environment not only shapes later health but also later romantic attachment experiences (Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, & Holland, 2013). The question, then, is whether romantic attachment experiences would in turn affect offspring care and health, a possibility that has not yet been studied much. To help bridge this gap, we have started examining the implications of partner responsiveness for the health of offspring. For instance, we found that mothers’ avoidant attachment to their partner was negatively associated with maternal responsiveness toward their toddlers (Selcuk, et al., 2010) and in another study, with responsiveness toward their adolescent children (Stanton, et al., 2016). Notably, maternal responsiveness, in turn, predicted greater (“healthier”) glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in youth with asthma (Stanton, et al., 2016), showing how partner responsiveness may affect not only one’s own health-related biology but also that of one’s offspring.

Another future step is for social and clinical psychologists to bring together their expertise in basic relationship processes and intervention science, respectively, in randomized trials investigating health effects of marital interventions. Interventions aiming at improving attachment security by removing the barriers in front of partners’ responsive behaviors toward each other have already been shown to be effective in alleviating marital distress over time (Johnson, et al., 2013) and such interventions targeting marital strains and strengths may lead to beneficial psychological and physiological changes conducive to a healthier and longer life.

Research in the area of close relationships and health is in an early stage of development, and objective measures of health and biomarkers of disease processes are still limited. However, preliminary evidence suggests that close relationships play an important role in our physical health and that the social psychology literature can provide answers to questions of what the psychological mediators and moderators of relationship-health links might be.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R01 HL114097, awarded to Richard B. Slatcher.

Contributor Information

Richard B. Slatcher, Wayne State University

Emre Selcuk, Middle East Technical University.

References

- Adams GC, Stoops Ma, Skomro RP. Sleep tight: Exploring the relationship between sleep and attachment style across the life span. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2014;18:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: Assessed in the strange situation and at home. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:953. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: An interactional perspective. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:39–63. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology. 1988;7:269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundes CP, Jaremka LM, Glaser R, Alfano CM, Povoski SP, Lipari AM, et al. Attachment anxiety is related to Epstein-Barr virus latency. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2014;41:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Owen MT, Holland AS. Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:817–838. doi: 10.1037/a0031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremka LM, Glaser R, Loving TJ, Malarkey WB, Stowell JR, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Attachment anxiety is linked to alterations in cortisol production and cellular immunity. Psychological Science. 2013;24:272–279. doi: 10.1177/0956797612452571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Moser MB, Beckes L, Smith A, Dalgleish T, Halchuk R, et al. Soothing the threatened brain: Leveraging contact comfort with emotionally focused therapy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79314–e79314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability. A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan CM, Iida M, Stephens MAP, Fekete EM, Druley JA, Greene KA. Spousal support following knee surgery: Roles of self-efficacy and perceived emotional responsiveness. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54:28–32. doi: 10.1037/a0014753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Poole L, Leigh E, Ronaldson A, Jahangiri M, Steptoe A. Attachment anxiety predicts IL-6 and length of hospital stay in coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2014;77:155–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology. 1999;18:63. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, Gunnar MR. Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin AJ, Dunbar RIM. The brain opioid theory of social attachment: A review of the evidence. Behaviour. 2011;148:985–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith P, Ownsworth T, Strong J. A review of the evidence linking adult attachment theory and chronic pain: Presenting a conceptual model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:407–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:501–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco PR, Uchino B, Dunkel Schetter C. Close relationship processes and health: Implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychology. 2013;32:499–513. doi: 10.1037/a0029349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT. In: Relationship well-being: The central role of perceived partner responsiveness. Hazan C, Campa MI, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Gable SL. Toward a positive psychology of relationships. In: Keyes CLM, Haidt J, editors. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:140–187. doi: 10.1037/a0031859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk E, Günaydin G, Sumer N, Harma M, Salman S, Hazan C, et al. Self-reported romantic attachment style predicts everyday maternal caregiving behavior at home. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk E, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness moderates the association between received emotional support and all-cause mortality. Health Psychology. 2013;32:231–235. doi: 10.1037/a0028276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk E, Stanton SC, Slatcher RB, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness predicts improved sleep quality through reduced anxiety. 2016 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Slatcher RB. Marital functioning and physical health: Implications for social and personality psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010;4:455–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00273.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slatcher RB, Selcuk E, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness predicts diurnal cortisol profiles 10 years later. Psychological Science. 2015;26:972–982. doi: 10.1177/0956797615575022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton SCE, Zilioli S, Briskin JL, Imami L, Tobin ET, Wildman DE, et al. Mothers’ attachment is linked to their children’s anti-inflammatory gene expression via maternal warmth. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1948550616687125. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Karlamangla AS, Friedman EM, Seeman TE. Early environment affects neuroendocrine regulation in adulthood. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;6:244–251. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM. It’s more than sex: exploring the dyadic nature of sleep and implications for health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:578–586. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181de7ff8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman D, Hazan C. Pair bonds as attachments: Reevaluating the evidence. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 436–455. [Google Scholar]

Recommended Readings

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Seminal article on the links between social relationships and health. 1988. See References. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. An excellent review of the biological processes underlying the associations between psychosocial factors and health. 2009. See References. [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM. A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of the past 50 years of research on the links between marital quality and physical health. 2014. See References. [Google Scholar]

- Slatcher RB. Review article that introduced the strength and strain model. 2010. See References. [Google Scholar]