Abstract

A life stage perspective is necessary for development of age-appropriate strategies to address substance use disorders (SUDs) and related health conditions in order to produce better overall health and well-being. The current review evaluated the literature across three major life stages: adolescence, adulthood, and older adulthood.

Findings

1) Substance use is often initiated in adolescence, but it is during adulthood that prevalence rates for SUDs peak; and while substance involvement is less common among older adults, the risk for health complications associated with use increases. 2) Alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and, increasingly, prescription medications, are the most commonly misused substances across age groups; however, the use pattern of these and other drugs and the salient impact vary depending on life stage. 3) In terms of health outcomes, all ages are at risk for overdose, accidental injury, and attempted suicide. Adolescents are more likely to be in vehicular accidents while older adults are at greater risk for damaging falls. Adulthood has the highest rates of associated medical conditions (e.g., cancer, sexually transmitted disease, heart disease) and mental health conditions (e.g., bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, antisocial personality disorder).

Conclusion

Prolonged heavy use of drugs and/or alcohol results in an array of serious health conditions. Addressing SUDs from a life stage perspective with assessment and treatment approaches incorporating co-occurring disorders are necessary to successfully impact overall health.

Keywords: Substance use disorder, psychiatric disorder, medical condition, comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

Substance use is a major public health concern that affects every level of society. Individuals, families, communities, and overall government spending is impacted by the use of licit and illicit substances. Recent reports estimated that annual costs in the United States are approximately USD $193 billion for illicit drug use,1 USD $223 billion for excessive alcohol use,2 and USD $193 billion for tobacco use.3 These costs include lost wages and productivity, criminal activity, and healthcare expenses. The economic burden aside, public health efforts can benefit from a better understanding of the impact of substance use disorder (SUD) on physical and mental health. Particularly, examining SUDs and the constellation of associated health and mental health problems throughout the lifespan provides a full picture of how variations in drug use patterns and outcomes shift with age, on which the present article will focus.

Adolescence represents a time in biological and social development that is associated with increased risk-taking behaviors; as such, experimentation with drugs and alcohol often begins in adolescence.4 Young brains are still changing as synaptic pruning continues into early adulthood,5 making the possibility for long-term negative effects of substance involvement even more profound. On the other end of the age spectrum, older adults also represent an extremely vulnerable group. The physiological changes that occur as a result of the natural aging process result in an increased use of multiple medications, drug and alcohol sensitivity, and the likelihood of co-occurring health conditions; thus, the risk for and consequences of SUDs are magnified.6–8

The purpose of the current review is to synthesize the research findings to date that examine physical and mental health problems associated with substance use at different stages of life. The goal is not to provide an exhaustive list of studies, but to emphasize the changing needs across the lifespan of those suffering from comorbidities in order to inform development of care and future research. In addition to presenting general patterns of alcohol, tobacco, and licit/illicit drug use, common and troublesome medical and psychiatric conditions associated with SUDs among adolescents, adults, and older adults are discussed. While some substances can result in significant consequences that are both acute and chronic (e.g., alcohol), the negative impact of others (e.g., tobacco) are primarily observed only after prolonged use. Finally, recommendations regarding clinical implications and areas for future research are presented.

Developmental Framework and Life Stages

Focal to the current review is the integration of studies across developmental periods which link substance use and health conditions. Biogenetic, psychological, and sociocultural factors vary in influence depending upon proximal (e.g., family, peer group, work setting) and distal (e.g., broader cultural, sociohistorical events such as wars or economic recession) contextual events over the lifespan.9–12 By placing the current literature within a developmental-contextual framework, we highlight what Bronfenbrenner10 terms “ecological transitions.” These transitions are characterized as “whenever a person’s position in the ecological environment is altered as a result of change in role, setting, or both.”10 We have organized the reviewed studies based on life stages marked by major developmental transitions. While specific age groupings may vary somewhat from study to study, the majority of research investigates substance involvement within one of three seminal life stages: adolescence, adulthood, and older adulthood. Table 1 summarizes examples from principal domains of developmental transitions relevant to each of the three life stages.

Table 1.

Major domains of developmental transitions influencing substance use and physical and mental health conditions

| Biological and Cognitive | Identity and Relationships | Achievement and Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescence | ||

-Pubertal development/hormonal changes

|

-Increased autonomy from family

-Increased interest & involvement in sexual & romantic relationships -Increased awareness & adherence to gender roles & norms |

Increased personal responsibility in school (i.e., less individualized instructor attention in high school & college) -Increased financial autonomy (e.g., more likely to have part-time job, pay some bills) |

| Adulthood | ||

| -Sexual maturation & greater hormonal stability -Neurocognitive brain maturation, specifically prefrontal cortex

|

-Greater stability in romantic relationship, such as marriage -Formation & commitment to one’s own family (i.e., spouse & children) -Legal maturity

|

-Full-time work with financial independence & responsibility (i.e., pay bills for self & family) -Intergenerational responsibility

|

| Older Adulthood | ||

| -Hormonal decline (i.e., menopause & decreased testosterone) leading to decreased reproductive capabilities -Decrease in neurocognitive functioning in speed of processing, working |

-Decreased autonomy due to physical &/or cognitive limitations -Lessened connection to extended family (e.g., possible death of spouse and/or family members, children move from home) |

-Reduced employment or retirement

|

Substance Use Patterns

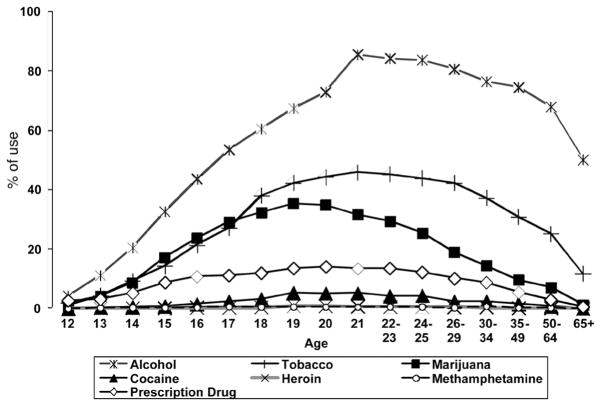

Large epidemiological surveys have shown alcohol, tobacco (i.e., cigarettes), and marijuana have the highest prevalence rates across all age groups.13 Figure 1 shows the percentage of people endorsing use in the past year (2011) for alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and prescription drug misuse (i.e., pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, sedatives). In early adolescence, prevalence rates of marijuana use were higher than tobacco; however, this appears to change in later teen years. Early adulthood shows the greatest amount of substance involvement, especially alcohol use. And while older adults are less likely to report past year substance use than most of their younger counterparts, prevalence rates for alcohol use remain relatively high.

Fig. 1.

Past-year substance use by age.

Source: Data from National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2011, N=58,397.13

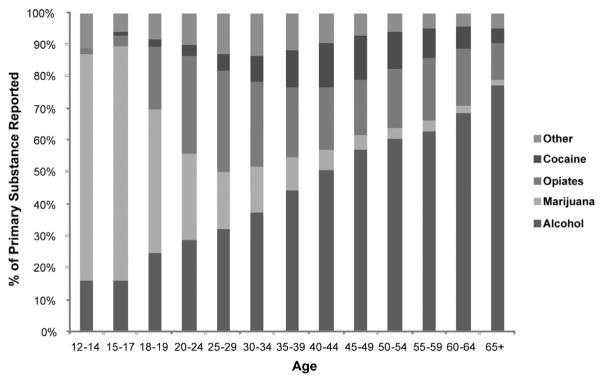

The Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS)14 presents US national-level data on demographic and substance abuse characteristics of admissions to treatment for abuse of alcohol and/or drugs. Figure 2 shows the distribution of primary substance of abuse reported at admission by age groups for treatment admissions in 2010. The majority of admissions are accounted for by four major substance groups: alcohol, marijuana, opiates, and cocaine. The remaining substances classified as “other” (methamphetamine, tranquilizers, sedatives, hallucinogens, PCP, inhalants, and “none specified”) are grouped due to low prevalence rates, particularly among youths and older adults. Adolescents largely seek treatment for marijuana use disorders, while older adults are largely in treatment for alcohol use disorders. The proportion of treatment admissions by drug group is most evenly distributed during adulthood.

Fig. 2.

Treatment admissions by age at admission and according to primary substance of abuse.

Source: Results from Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 2010, N=1,820,737.14

Of the almost two million treatment admissions reported by TEDS,14 less than 40,000 were accounted for by those 60 or over. While many adults “mature out” of heavy drinking and illicit drug use during the second half of life,15 prevalence rates among older adults are also affected by higher mortality rates among drug users. Epidemiological surveys are not based on longitudinal data sets and therefore do not track the course of drug involvement over time. Hser and colleagues’ 33-year follow-up study of narcotics addicts showed high rates of mortality among drug users, most commonly attributed to accidental poisoning or overdose.16 Premature mortality is believed to be a function of substance use and lifestyle.

DISCUSSION

Table 2 summarizes the substances and associated health conditions that are most prominently featured in the literature. Again, while not exhaustive lists, the mental and physical health problems highlighted here represent areas we believe are of great public health importance.

Table 2.

Summary substance use patterns and associated mental and physical health conditions by life stage

| Substance Use | Physical/Medical Conditions | Mental Health/Psychiatric Disorders |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescence | ||

| Alcohol Marijuana Tobacco Inhalants Psychotherapeutic Drugs

|

Accidental Injury

Poisoning/Overdose Sexually Transmitted Diseases Respiratory Problems

|

Suicidal Ideation/Behaviors Internalizing Disorders

|

| Adulthood | ||

| Alcohol Marijuana Tobacco Psychotherapeutic Drugs

Heroin Methamphetamine |

Poisoning/Overdose Sexually Transmitted Diseases Cancers Heart Disease/Hypertension/Stroke Reproductive Morbidity/Fetal Damage Diabetes Respiratory Problems

|

Suicidal Ideation/Behaviors Mood Disorders

|

| Older Adulthood | ||

| Alcohol Psychotherapeutic Drugs

Tobacco |

Accidental Injury Cirrhosis Heart Attack/Stroke Insomnia Cancers Diabetes |

Suicidal Ideation/Behaviors Depression/Bereavement Anxiety Disorders

Insomnia |

Adolescence

Although legal and practical barriers are most restrictive for teen users, substance use remains an area of concern due to the potentially hazardous short- and long-term consequences. The leading cause of accidental injury and death (e.g., automobile accidents, suicide) among adolescents is precipitated by substance use.17 Maladaptive behavioral patterns associated with later physical and mental health problems are formed and consolidated during this time.18–20 Thus, examination of substance use and outcomes among adolescents can help tailor interventions and maximize long-term benefits.

Physical Health/Medical Conditions

Adolescence is a period marked by significant developmental changes. As such, even moderate substance use can cause harm. Behaviors associated with drinking and drug use in teens contribute to increased risk for injury and violence.21 US national survey results indicate that within the month prior to survey, 24.1 percent of high school students reported being a passenger in a car when the driver had been drinking and 8.2 percent reported having driven a car themselves after consuming alcohol.21 An examination of older adolescents revealed that one in six college students reported drugged driving (i.e., illicit drugs or prescription drugs used non-medically) in the past year.22 The combination of limited driving experience and impaired motor skills results in increased rates of injuries and fatalities from traffic accidents.

Substance using adolescents also frequently engage in risky sexual behaviors.23,24 Among sexually active high school students, 22.1 percent report having used drugs or alcohol prior to their most recent sexual intercourse.24 Consequently, substance use and corresponding risky sexual behaviors have shown consistently strong associations with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among teens.23,25,26 Unprotected sex and history of sex with multiple partners is more likely among both social and chronic substance users well into late adolescence.27–29 Recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data24 show the magnitude of this risk, with young people accounting for over a quarter of new HIV infection cases; almost 60 percent of those infected did not know their HIV status. Yan and colleagues30 examined the relationship between substance use and HIV/STD-related sexual risk behaviors more closely. In their national sample of sexually active teens living in rural US settings, they found that smoking three or more days in the past month was significantly associated with not using condoms. Recent and lifetime drug and alcohol use were related to having multiple sexual partners. It appears that substance use and risky sexual behavior represent part of a constellation of reckless behaviors, some of which are normative while others are the result of social deficits.30,31

Adolescents diagnosed with an SUD show more acute and potentially chronic health problems than teens without SUD. Nonmedical use of prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications accounted for approximately half of emergency department (ED) visits for drug abuse or misuse in the US in 2011; among youth aged 12–17, the proportion of those seeking emergency medical care due to pharmaceutical misuse exceeds that of alcohol (301 ED visits versus 160 ED visits per 100,000 population).32 The risk for substantial harm is increased when medications are abused with one another and/or alcohol.

Specific, chronic health problems can be difficult to detect in a younger population; however, Mertens, Flisher, Fleming and Weisner33 found that prevalence rates for one-fourth of the comorbid medical conditions examined were greater among substance-using teens. In particular, asthma and pain-related diagnoses surfaced as common and costly health conditions among the patient group. Myers and Brown34,35 found that independent of other drug involvement, respiratory problems continued from two to four years after substance abuse treatment for adolescent smokers. Although definitive causal relationships across medical conditions are difficult to discern, continued substance involvement can exacerbate symptoms, and for some, lead to more severe, life-threatening disorders.

Mental Health/Psychiatric Disorders

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors directly link mental health to physical well-being. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among American youth age 10–19.36,37 Although substance use is not always the “cause” of suicidal ideation or attempts, it is a significant risk factor.38 Teens with SUDs have been found to be about three times more likely to make a suicide attempt as compared to non-drug-using adolescents.39 In a study examining data from a community sample of youth, suicide attempts were strongly associated with alcohol abuse and dependence, even after controlling for depression.40 These findings highlight the need to better understand the role that substance use and abuse plays in suicidal thoughts and actions, both in the presence and absence of mental health conditions.

Among clinical samples, high rates of comorbidity exist during adolescence.41 Approximately 70–80 percent of youths presenting to treatment are dually diagnosed.42 Comorbidity patterns, however, vary by substance type, severity of SUD, and psychiatric disorder.43 For instance, while internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression) are prevalent in both clinical and general adolescent populations,44,45 many studies indicate gender differences in co-occurrence for mood disorders. Specifically, rates of depression are higher for girls than boys with SUDs.43,46–48 Shrier and colleagues49 examined this further by assessing psychiatric symptoms among youth with sub-diagnostic substance use problems within a primary care setting. They found that girls exhibiting substance use problems were more likely to report symptoms of mood disturbance. Anxiety symptomology has been found to be highly prevalent for both adolescent boys and girls with diagnostic or problematic use,43,49 with about seven percent of youths with an SUD meeting criteria for any anxiety disorder within the past year.43

While the exact sequencing of psychiatric symptoms and substance use can vary by individual, there is some evidence that externalizing disorders typically precede SUDs.50–53 Disorders such as Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Conduct Disorder (CD), and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are characterized by their childhood or adolescent onset and constellation of disruptive and maladaptive behaviors.54 Externalizing symptoms have been associated with sub-diagnostic drug and alcohol use for both male and female adolescents,49,51 suggesting an association between behavioral disturbance and problematic use prior to full SUD criteria. However, epidemiologic data indicate that SUDs are associated with greater odds of comorbid CD and ODD.43 Taken together, the evidence suggests the co-occurrence of substance use, problematic or diagnostic, and socially harmful behaviors may be interacting and possibly exacerbating one another.43,55 While limited social responsibilities during adolescence may restrict the impact of these behaviors, the combination of ongoing substance involvement and maladaptive behavior can set the stage for greater impairment as youth move into adulthood.

Adulthood

Referring once again to Bronfenbrenner’s10 developmental framework, the ecological transition from adolescence to adulthood is marked by profound changes. Prevalence rates for drugs and alcohol increase during late adolescence;17 however, most individuals transition out of this drinking and drug use pattern.56,57 The multilevel developmental contextual approach recognizes that a move into SUD is influenced by multiple factors within a dynamic, probabilistic process.58

Physical Health/Medical Conditions

The impact of SUDs on physical health is most easily seen in terms of acute effects. Intoxication, misuse, and overdose can be life-threatening and result in medical emergencies. In 2011, the majority of ED visits in the US related to illicit drugs was accounted for by adults (21–64 years).32 Young adults had the highest rates of medical emergencies involving marijuana, heroin, and amphetamine/methamphetamines in comparison to other age groups. However, a recent morbidity and mortality report reveals that opioid analgesic poisoning was related to more deaths than heroin or cocaine, the majority of which were aged 35–54.59 Prescription medication misuse poses as much of a threat to health as traditional street drugs. Unfortunately, the consequences of non-medical use of prescription drugs may continue to rise as the younger generations with access to pharmaceuticals ages and social acceptance of medication sharing continues.

In addition to acute problems, SUDs can result in general health deterioration and specific, ongoing conditions. In a 14-year prospective study of young adults reporting “good” or better health at intake, baseline hard drug use was significantly associated with subsequent self-rated health decline as compared to never using.60 They found even if drug use stopped, the decline continued. The authors identified tobacco use as a significant factor for lack of restored health. These results are consistent with national studies in which 77–93 percent of clients in SUD treatment settings use tobacco products61 and over 50 percent die of tobacco-related causes.62 The combination of multiple substances substantially increases the risk for health problems. For instance, while cancers of the mouth and throat are seven and six times greater for tobacco and alcohol users respectively, the risk is 38 times more for those who use both substances.63 Cigarette smoking in particular has been linked to 90 percent of all cases of lung cancer and accounts for approximately one-third of all cancer deaths.64 While the research regarding marijuana smoking and lung cancer remains inconclusive,65 there is evidence for increased risk of respiratory illnesses among regular marijuana smokers.66,67

Several substances (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, heroin, prescription stimulants, methamphetamine) have been linked to increased risk for cardiovascular problems and heart disease.64 As a stimulant, cocaine immediately and directly impacts blood pressure; thus, the resulting increased risk for heart attack and cardiac arrest seems an obvious one.64,68 There is, however, a strong and consistent relationship between long-term alcohol use and hypertension as well.69–71 In fact, heavy drinking is purported to be the most common cause of secondary hypertension.72,73 Although it appears these effects are often reversible with sustained abstinence, blood pressure quickly returns to elevated levels upon relapse.73,74 Over time, continued use and hypertension increase the risk for cereborvascular accidents, with binge drinking being a significant risk factor for all subtypes of stroke.75 The physical and mental impairment from stroke is potentially large and irreversible; thus, cardiovascular health is an important issue in individual and public health.

Substance use also increases risk for infectious disease. Drug and needle sharing practices can lead to infection of HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), and other blood-borne pathogens. Injection drug users (IDUs) are the highest risk group for acquiring HCV; approximately 70 to 80 percent of new HCV cases in the US each year are among IDUs.76–78 Similarly, injection drug use, both directly and indirectly, is a significant contributor to the spread of HIV. More than one-third of AIDS cases in the US are due to IDUs, people who have sex with IDUs, and children born to mothers who have contracted HIV through drug use practices.79 HIV and HCV infection rates specifically among crack cocaine users is also accounted for by sharing of pipes among users with open mouth sores, increased risky sexual behavior, and sex work (i.e., trading sex for crack or money).80–82 Similarly, methamphetamine use, whether injected, snorted, or smoked, is associated with increased risk for HIV and other STDs, particularly among men who have sex with men.83 Regardless of sexual orientation, however, sexual risk practices such as reduced condom use, being high during sex, and having multiple sexual partners is prevalent among methamphetamine users.84,85 Once contracted, the course of sexually transmitted infectious disease carries with it a long-term, cost-heavy burden for treatment.

Mental Health/Psychiatric Disorders

Adults diagnosed with an SUD and comorbid mental health disorder are at increased risk for poor health, social dysfunction, incarceration, poverty, and homelessness.86,87 Anxiety disorders represent some of the most commonly co-occurring disorders, with significant associations between any anxiety disorder and any drug dependence.88–90 Among the general US population, 30 percent of those meeting criteria for any lifetime drug use disorder had at least one anxiety disorder.88 In particular, sedative, opioid, and tranquilizer use disorders have shown a strong association with anxiety disorders.90,91 Women have demonstrated greater comorbidity between these specific SUDs and anxiety disorders, especially social and specific phobias.88,91 Although epidemiologic surveys cannot definitively support the self-medication hypothesis, some speculate that the calming effects of these drugs play a role in their link to comorbid anxiety.

Although post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is also classified as an anxiety disorder, its fundamental component of resulting from a traumatic event sets it apart. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the general population is estimated to be less than eight percent;92,93 however, the lifetime prevalence rate of PTSD among adults with a drug or alcohol use disorder ranges from a quarter to a half in clinical samples.94,95 The relationship between trauma and SUDs is believed to be bidirectional. Heavy drug and alcohol use places individuals at risk for victimization; and conversely, those who have experienced a traumatic event often cope with the symptoms (e.g., insomnia, hyperarousal, intrusive thoughts) by using drugs and alcohol.90,96,97 Ouimette and colleagues97 demonstrated the impact that PTSD symptoms and substance use have on one another by monitoring dually diagnosed out-patients for 26 weeks. Results indicated that PTSD symptoms and alcohol and cocaine symptoms fluctuated concurrently week to week. These findings and high rates of comorbidity speak to the need for assessments and treatments that address both.

Mood disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar I and II, have consistently demonstrated most common co-occurrence with SUDs among adults.88,90,98,99 Individuals meeting criteria for MDD are approximately twice as likely to have SUD as those with no mood disorder diagnosis.90,98,100,101 The risk of a comorbid SUD is even greater among those with bipolar disorder, with estimates indicating a seven times greater likelihood.90 In a 20-year prospective study by Merikangas and colleagues,102 results indicated that people who reported symptoms of mania, but did not meet full diagnostic criteria for bipolar I or II, were at an increased risk for developing an alcohol use disorder. Furthermore, those diagnosed as bipolar II showed even greater risk for developing an alcohol use disorder or benzodiazepine use problem. Of particular concern is the increased risk for suicide attempts and completion within this population.103 The stronger association between mood disorders and SUDs among women has potentially grave implications beyond the individual.88 Mental health status and associated impairment can affect child rearing and the family environment when mothers suffer from comorbidity.104

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is commonly discussed in the literature because of its significant and consistent relationship with SUDs.88,105 ASPD is more often diagnosed in men and is defined by a failure to conform to social norms and a persistent disregard for the rights of others.54 Compared to the general public, prevalence rates of ASPD are higher among prisoners and those in drug and alcohol treatment settings.106,107 The co-occurrence of these disorders is associated with greater severity and poorer prognosis; substance use is initiated earlier and the progression into dependence occurs more quickly.108 Substance use combined with the pervasive impulsivity and aggression characteristic of ASPD can result in problematic family relationships and increased recidivism among those who have been criminally convicted.106,109 Treating ASPD patients is often challenging. Establishing a good therapeutic alliance is difficult and many refuse services or terminate early unless required by an external source (e.g., condition of parole).110 The transition into later adulthood for these individuals is likely to be a difficult one, with little positive social support and poor health.

Older Adulthood

Although Bronfenbrenner’s10 developmental framework focuses more on understanding how a child’s interaction with the external world shapes internal processes and behaviors, ecological systems continue to influence functioning as adults age. Older adults tend to experience fewer traditional responsibilities, such as full-time employment or parenthood; however, the natural aging process brings other notable social, cognitive, and physiological challenges. And while substance use generally declines in later adulthood, even small amounts of drug and alcohol use can have serious consequences. Physical aging and commonly used medications can result in increased sensitivity to the effects of substance use,8,111 elevating the risk for impairment and accidental death.112

Physical Health/Medical Conditions

Substance use disorders in older adults may be a continuation of excessive drug and alcohol use initiated while younger, but for some, substance use begins during times of transition or loss. For instance, health declines that accompany older age may lead to reduced independence or associated pain; drug and alcohol use therefore provides an emotional escape from boredom and loneliness.113 Unfortunately, the combination of existing chronic conditions and substance use or misuse can result in exponentially negative effects on physical health.113,114 Older adults are more likely to experience adverse events from psychoactive medications, and due to the increased likelihood of older adults being prescribed multiple medications, the risk for serious drug interactions is high and often requires emergency medical care.115–117 Additionally, prescription medication use, such as regular use or misuse of sedatives and benzodiazepines, has been associated with increased risk for falls in older populations.116,118 When alcohol is combined with prescription medications, the effects appear even more detrimental. In a national study of Medicare beneficiaries, heavy drinking more than doubled the risk for hip fractures.111 All of these can lead to costly hospital admissions and lengthy stays.

The impact of drugs and alcohol on blood pressure and insulin production can greatly increase the risk for heart attack and stroke. In a population-based cohort study of cardiovascular health among older adults, nine-year follow-up data demonstrated modestly lowered risk for stroke among light drinkers; however, alcohol consumption greater than six drinks per week was associated with increased risk.119 Although the relationship between cardiovascular health risks and alcohol use may be somewhat inconsistent, the link between tobacco use and heart and cerebrovascular disease is very clear, with smoking being a major risk factor in these leading causes of death among those 60 and over.120,121 The increased prevalence of smoking and non-medical use of prescription drugs among older adults who drink more heavily places this group at high risk for premature death. Unfortunately, however, few interventions are tailored to older adults and may fail to address their specific needs and concerns.

Substance-using older adults are at increased risk for organ damage and various cancers. In particular, the ten-year risk for developing breast cancer among women age 60 and over is more than double than that of their 40-year-old counterparts; regular alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking are considered significant and controllable risk factors for the disease.122 Similarly for men, risk for colorectal and prostate cancer quickly increases with age, with substance involvement amplifying risk.120,122 Additionally, although women are more sensitive to the effects of long-term alcohol use, alcoholic men are approximately two to six times more likely to be diagnosed with cirrhosis in comparison with alcoholic women.123,124 Thus, gender appears to be an important factor in determining the health needs of older adults.

Mental Health/Psychiatric Disorders

Mental health disorders are associated with significant disability in older adults. Mental capacity can compromise quality of life, increase mortality, and decay physical health.125 Multiple cognitive deficits, most prominently memory difficulties, that are severe enough to cause significant impairment in functioning are classified as dementia.54 While chronic alcohol use can be detrimental to memory function and at times result in Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome,126,127 some evidence indicates limited alcohol intake may be protective against developing dementia as adults age. A recent meta-analysis on alcohol consumption and cognitive decline in older adults showed moderate drinking was associated with a reduced risk for dementia.128 Conversely, even small amounts of alcohol can potentially intensify the effects of many commonly used prescription (e.g., benzo-diazepines) and over-the-counter medications (e.g., antihistamines).129,130 Resulting confusion can impact even simple tasks like personal hygiene and self-grooming, making independent living less possible.129–131 Since individual differences appear to be even greater among older adults, physician-monitoring of substance use and misuse is of increased importance for overall safety.

Like all stages of life, older adults are at risk for depression and anxiety. Among older adults meeting criteria for panic disorder, approximately 36.7 percent are comorbid for current MDD.132 In a survey among older adults admitted for SUD treatment, anxiety and depression were cited as the top reasons for misusing substances.133 Older women are particularly high risk for comorbidity; they receive twice the number of prescription medications as men, making them vulnerable to drug misuse.130,134 More severe depressive symptoms, especially those caused by bereavement, can result in suicide attempts. Rates of completed suicide are most prevalent among older white men who drink heavily after the loss of their spouse.135 In terms of ecological transitions, the loss of loved ones and erosion of independence are the hallmarks of older adulthood. Both can have significant impacts on mood and functioning.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Adolescents may only see the beginnings of emerging medical and psychiatric complications, either resulting from or exacerbating their substance use, and therefore issues of comorbidity may not be adequately assessed or addressed in treatment. Further, substance use or psychotherapeutic misuse may not be identified as a primary problem among older adults during doctor visits. Physicians and patients may assume medical and mental health symptoms are the result of normal aging and therefore not assess substance involvement.136 Despite the prevalence of SUDs among adult men and women, most never receive formal treatment.137 The majority of those who do seek out services do so through self-help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous); they report lack of health care coverage and not being ready to stop using as the top reasons for not receiving treatment.32

In order to address this gap in care, healthcare systems should have improved integrated care for mental health, medical conditions, and SUDs. Increased training for physicians in how to assess for SUDs and mental health disorders could help them better identify and refer patients in need of specialized services. Patients’ reluctance to reduce or stop using may be better combated if physicians were able to adequately identify and communicate how substance use was impacting specific health conditions. Personal relevance along with a more complete picture of how behaviors affect well-being may assist in promoting and sustaining behavioral change.

Additionally, integrated care for SUDs and health conditions will require ongoing assessment and support. Just as medication adherence is monitored through the use of self-management tools (e.g., pill boxes, alarms), frequency and quantity of drug, alcohol, and tobacco use must also be regularly assessed by the individual as well as during doctor visits. As technology advances, self-regulation tools are being increasingly adapted into smartphone applications and web-based formats. These can range from simple recordings of daily or weekly use and mental or physical health symptoms, to interactive phone apps or websites that patients can access if in need of support or information. Both are useful and economical adjuncts to help healthcare professionals and individuals monitor health behaviors and symptoms over the long-term. Drug and alcohol use and misuse can occur at any age with negative consequences; therefore, ways to provide empirically supported treatments and individualized care are necessary across all life stages.

In order to achieve these goals, future research would benefit from longitudinal studies to monitor relapse and remission, and explore the changes in risk and protective factors as people age. Teens have parental monitoring to help deter them from using drugs and alcohol, but older adults are likely to have fewer social contacts so variations in their substance use patterns may go unnoticed. Additional studies are needed to explore differences in drug and alcohol use among other populations and diverse settings, such as third-world countries, assisted living/nursing facilities, and women. Finally, it is important that SUDs research utilizes a developmental-contextual framework in order to acknowledge and understand how external variables (e.g., war, economic recession, information/technology age, social media) influence drug and alcohol use, perceptions of substance use, and mental and physical well-being.

SUMMARY

The physical, emotional, and social needs and resources of individuals change as they grow older. Internal (e.g., neurocognitive, hormonal) and external (e.g., parenthood, occupational responsibilities) factors influence shifts in substance involvement over time and subsequently, wield great influence over health status. For many adolescents, the developmental move into adulthood results in a natural decrease in substance use; however, for some, adulthood moves them from “gateway” drugs into more disordered use of illicit drugs. While older adults may appear to be the least likely to misuse substances, our large aging population, combined with increased physical vulnerability and the common use of multiple pharmaceuticals, makes them a group with rising needs for intervention services. In fact, tracking developmental changes over the lifespan highlights the need for specialized services not only for SUDs, but for coordinated care attending to the associated mental and physical health problems. As described within this review, these issues do not exist in isolation. Older adults may experience decreased medication effectiveness or risk for hip fracture because of alcohol use; and among adults, stopping substance use may be hindered by unmanaged PTSD or depression symptoms. Although health consequences of use may be mild or not immediate for many teens, the initiation of regular substance involvement during adolescence can greatly impact neurological development and lead to more disordered use in adulthood. Regardless of whether the psychiatric or medical condition preceded or resulted from substance use, it appears that continued involvement in drinking, smoking, and/or using drugs exacerbates symptoms and potentially strains healthcare services.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support from Center for Advancing Longitudinal Drug Abuse Research (P30DA016383 from NIDA; PI: Hser).

Acronyms List

- ASPD

Antisocial personality disorder

- CD

Conduct disorder

- ED

Emergency department

- HCV

Hepatitis C

- IDU

Injection drug user

- MDD

Major depressive disorder

- ODD

Oppositional defiant disorder

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- STD

Sexually transmitted diseases

- SUD

Substance use disorder

- TEDS

Treatment Episode Data Set

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center. The economic impact of illicit drugs use on American society. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Justice; Apr, 2011. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. Available from URL: http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44731/44731p.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouchery E, Harwood H, Sacks C, Simon C, Brewer R. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:516–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. [Accessed 16 September 2013];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008 57:1226–8. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5745a3.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown SA, Tapert SF. Adolescence and the trajectory of alcohol use: basic to clinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:234–44. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore AA, Giuli L, Gould R, Zhou K, Reuben D, et al. Alcohol use, comorbidity, and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:757–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore AA, Whiteman EJ, Ward KT. Risks of combined alcohol/medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moos RH, Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS. High-risk alcohol consumption and late-life alcohol use problems. Am J Pub Health. 2004;94:1985–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baltes PB. Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: on the dynamics between growth and decline. Develop Psych. 1987;23:611–26. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerner RM, Kauffman MB. The concept of development in contextualism. Develop Rev. 1985;5:309–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sameroff AJ. The societal context of development. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Contemporary Topics in Developmental Psychology. New York (NY): Wiley; 1987. pp. 273–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Sep, 2012. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Available from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/2k11results/nsduhresults2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National admissions to substance abuse treatment services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Jun, 2012. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2000–2010. DASIS Series S-61, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4701. Available from URL: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/TEDS2010N/TEDS2010NWeb.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menninger JA. Assessment and treatment of alcoholism and substance-related disorders in the elderly. B Menninger Clin. 2002;66:166–84. doi: 10.1521/bumc.66.2.166.23364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin D. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor (MI): Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Feb, 2012. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. Available from URL: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman HL. Adolescent and social development: a global perspective. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:588–94. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90191-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jessor R. Adolescent development and behavioral health. In: Matarazzo JD, Perry CL, editors. Behavioral Health: A Handbook of Health Enhancement and Disease Prevention. New York (NY): Wiley; 1984. pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson AC, Leffert N, Graham B, Alwin J, Ding A. Promoting mental health during the transition to adolescence. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health Risks and Developmental Transitions during Adolescence. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 471–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arria AM, Garnier-Dykstra LM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, O’Grady KE, Wish ED. Persistent nonmedical use of prescription stimulants among college students: possible association with ADHD symptoms. J Attention Disorders. 2011;15:347–56. doi: 10.1177/1087054710367621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, McCombs S. Exposure to violence and associated health-risk behaviors among adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1238–42. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.11.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: HIV infection, testing, and risk behavior among youths - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:971–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kingree JB, Braithwaite R, Woodring T. Unprotected sex as a function of alcohol and marijuana use among adolescent detainees. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:179–85. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowry R, Holtzman D, Truman BI, Kann L, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ. Substance use and HIV-related sexual behaviors among US high school students: are they related? Am J Pub Health. 1994;84:1116–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1035–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riehman KS, Wechsberg WM, Francis SA, Moore M, Morgan-Lopez A. Discordance in monogamy beliefs, sexual concurrency, and condom use among young adult substance-involved couples: implications for risk of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:677–82. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218882.05426.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tapert SF, Aarons GA, Sedlar GR, Brown SA. Adolescent substance use and sexual risk-taking behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:181–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan AF, Chiu YW, Stoesen CA, Wang MQ. STD-/HIV-related sexual risk behaviors and substance use among US rural adolescents. J Nat Med Assoc. 2007;99:1386–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: one-year follow-up of a school-based prevention intervention. Prev Sci. 2001;2:1–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010025311161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; May, 2013. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Available from URL: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mertens JR, Flisher AJ, Fleming MF, Weisner CM. Medical conditions of adolescents in alcohol and drug treatment: comparison with matched controls. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers MG, Brown SA. Smoking and health in substance abusing adolescents: a two year follow-up. Pediatrics. 1994;93:561–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers MG, Brown SA. Cigarette smoking four years following treatment for adolescent substance abuse. J Adolesc Subst Abuse. 1997;7:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kochanek KD, Kirmeyer SE, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129:338–48. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin JA, Kung HC, Mathews TJ, Hoyert DL, Strobino DM, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2006. Pediatrics. 2008;121:788–801. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–10. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bukstein OG, Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Baugher M, et al. Risk factors for completed suicide among adolescents with a lifetime history of substance abuse: a case-control study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:403–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu P, Hoven CW, Liu X, Cohen P, Fuller CJ, Shaffer D. Substance use, suicidal ideation and attempts in children and adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34:408–20. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.4.408.53733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storr CL, Pacek LR, Martins SS. Substance use disorders and adolescent psychopathology. [Accessed 4 February 2014];Pub Health Rev. 2012 34:442–84. Available from URL: http://www.publichealthreviews.eu/show/p/107. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaminer Y, Bukstein OG, editors. Adolescent Substance Abuse: Psychiatric Comorbidity and High Risk Behaviors. New York (NY): Taylor and Francis; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Rates of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among adolescents in a large metropolitan area. J Psych Res. 2007;41:959–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Couwenbergh C, van den Brink W, Zwart K, Vreugdenhil C, van Wijngaarden-Cremers P, van der Gaag RJ. Comorbid psychopathology in adolescents and young adults treated for substance use disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:319–28. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bukstein OG, Glancy LJ, Kaminer Y. Patterns of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagnosed adolescent substance abusers. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1992;31:1041–5. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGuinness TM, Dyer JG, Wade EH. Gender differences in adolescent depression. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2012;50:17–20. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20121107-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nolen-Hoeksema S. An interactive model for the emergence of gender differences in depression in adolescence. J Research Adolesc. 1994;4:519–34. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. Pediatrics. 2003;111:699–705. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Faraone SV, Weber W, et al. Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:21–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molina BS, Pelham WE., Jr Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT. Parsing the undercontrol/disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: a multilevel developmental problem. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5:248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington (DC): The Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Adolescent health behavior and conventionality-unconventionality: an extension of problem-behavior therapy. Health Psychol. 1991;10:52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White W. Recovery across the life cycle. Alcohol Treat Q. 2006;24:185–201. doi: 10.1300/J020v24n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Windle M. A multilevel developmental contextual approach to substance use and addiction. Biosocieties. 2010;5:124–36. doi: 10.1057/biosoc.2009.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paulozzi LJ, Annest J. Unintentional poisoning deaths—United States, 1999–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kertesz SG, Pletcher MJ, Safford M, Halanych J, Kirk K, et al. Illicit drug use in young adults and subsequent decline in general health: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:224–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richter KP, Gibson CA, Ahluwalia JS, Schmelzle KH. Tobacco use and quite attempts among methadone maintenance clients. Am J Pub Health. 2001;91:296–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. JAMA. 1996;275:1097–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Alert. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;71:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Accessed 2 July 2013];Medical Consequences of Drug Abuse. 2005 May; Available from URL: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/

- 65.Boffetta P, Hashibe M. Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncology. 2006;7:149–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Polen MR, Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Sadler M, Friedman GD. Health care use by frequent marijuana smokers who do not smoke tobacco. West J Med. 1993;158:596–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moore BA, Auguston EM, Moser RP, Budney AJ. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a U.S. sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:33–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kontos MC, Jesse RL, Tatum JL, Ornato JP. Coronary angiographic findings in patients with cocaine-associated chest pain. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00660-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chou SP, Grant BF, Dawson DA. Medical consequences of alcohol consumption—United States, 1992. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1423–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gutjahr E, Gmel G, Rehm JUR. Relation between average alcohol consumption and disease: an overview. Eur Addict Res. 2001;7:117–27. doi: 10.1159/000050729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xin X, He J, Frontini MG, Ogden LG, Motsamai OI, Whelton PK. Effects of alcohol reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2001;38:1112–7. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.093424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clark L. Alcohol-induced hypertension: mechanisms, complications, and clinical implications. J Natl Med Assoc. 1985;77:385–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klatsky AL, Gunderson E. Alcohol and hypertension: a review. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2:307–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Potter JF, Beevers DG. Pressor effect of alcohol in hypertension. Lancet. 1984;323:119–22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hillbom M, Saloheimo P, Juvela S. Alcohol consumption, blood pressure, and the risk of stroke. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:208–13. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0194-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bourgois P, Lettiere M, Quesada J. Social misery and the sanctions of substance abuse: confronting HIV risk among homeless heroin addicts in San Francisco. Social Problems. 1997;44:155–73. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koester S, Glanz J, Baron A. Drug sharing among heroin networks: implications for HIV and hepatitis B and C prevention. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:27–39. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1679-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koester S, Heimer R, Barón AE, Glanz J, Teng W. RE: “Risk of Hepatitis C virus among young adult injection drug users who share injection equipment”. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:376. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug-associated HIV transmission continues in the United States. Atlanta (GA): CDC; Mar 8, 2007. [Accessed 2 July 2013]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/idu.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Azevedo RCSD, Botega NJ, Guimaraes LAM. Crack users, sexual behavior and risk of HIV infection. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;29:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collins CL, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Marsh DC, Kretz PS, et al. Rationale to evaluate methodically supervised safer smoking facilities for non-injection illicit drug users. Can J Pub Health. 2004;95:344–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03404029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCoy CB, Lai S, Metsch LR, Messiah SE, Zhao W. Injection drug use and crack cocaine smoking: independent and dual risk behaviors for HIV infection. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Buchacz K, McFarland W, Kellogg TA, Loeb L, Holmberg SD, et al. Amphetamine use is associated with increased HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS. 2005;19:1423–4. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180794.27896.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 1998;168:93–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Celetano DD, Latimore AD, Mehta SH. Variations in sexual risks in drug users: emerging themes in a behavioral context. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:212–8. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kessler RC. The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:730–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Brien CP, Charney DS, Lewis L, Cornish JW, Post RM, et al. Priority actions to improve the care of persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders: a call to action. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:703–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:247–57. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goodwin RD, Stein DJ. Anxiety disorders and drug dependence: evidence on sequence and specificity among adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:167–73. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, Niv N, Moore AA. Gender and comorbidity among individuals with opioid use disorders in the NESARC study. Addic Behav. 2009;34:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.National Center for PTSD. Facts about PTSD. [Accessed 19 September 2013];Psych Central. 2006 Available from URL: http://psychcentral.com/lib/facts-about-ptsd/000662.

- 93.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mills KL, Lynskey M, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S. Post-traumatic stress disorder among people with heroin dependence in the Australian treatment outcome study (ATOS): prevalence and correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reynolds M, Mezey G, Chapman M, Wheeler M, Drummond C, Baldacchino A. Co-morbid posttraumatic stress disorder in a substance misusing clinical population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Riggs DS, Rukstalis M, Volpicelli JR, Kalmanson D, Foa EB. Demographic and social adjustment characteristics of patients with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: potential pitfalls to PTSD treatment. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1717–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ouimette P, Read JP, Wade M, Tirone V. Modeling associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and substance use. Addict Behav. 2010;35:64–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Merikangas KR, Herrell R, Swedsen J, Rossler W, Ajdacic-Gross V, Angst J. Specificity of bipolar spectrum conditions in the comorbidity of mood and substance use disorders: results from the Zurich cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:47–52. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dalton EJ, Cate-Carter TD, Mundo E, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL. Suicide risk in bipolar patients: the role of co-morbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:58–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hser YI, Lanza HL, Li L, Kahn E, Schulte M. Maternal mental health and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors: beyond maternal substance use disorders. 2013. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 2300 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet. 2002;359:545–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hare RD. Diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder in two prison populations. Am J Psych. 1983;140:887–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.7.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ford JD, Gelrnter J, DeVoe JS, Zhang W, Weiss RD, et al. Association of psychiatric and substance use disorder comorbidity with cocaine dependence severity and treatment utilization in cocaine-dependent individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mueser KT, Gottlieb JD, Cather C, Glynn SM, Zarate R, et al. Antisocial personality disorder in people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: clinical, functional, and family relationship correlates. Psychosis. 2012;4:52–62. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2011.639901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gabbard GO, Gunderson JG, editors. Review of Psychiatry. 1. Vol. 19. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. Psychotherapy for Personality Disorders; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Patterson TL, Jeste DV. The potential impact of the baby-boom generation on substance abuse among elderly persons. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1184–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yuan Z, Dawson N, Cooper GS, Einstadter D, Cebul R, Rimm AA. Effects of alcohol-related disease on hip fracture and mortality: a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Public Health. 2000;91:1089–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Royal College of Psychiatrists. College Report CR165. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; Jun, 2011. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. Our invisible addicts: first report of the Older Persons’ Substance Misuse Working Group of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Available from URL: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/cr165.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bucholz KK, Sheline Y, Helzer JE. The epidemiology of alcohol use, problems, and dependence in elders: a review. In: Beresford TP, Gomberg E, editors. Alcohol and Aging. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reid MC, Anderson PA. Geriatric substance use disorders. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:999–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sorock GS, Shimkin EE. Benzodiazepine sedatives and the risk of falling in a community dwelling cohort. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2441–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, McCormick D, Jain S, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1629–34. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sheahan SL, Coons SJ, Robbins CA, Martin SS, Hendricks J, Latimer M. Psychoactive medication, alcohol use, and falls among older adults. J Behav Med. 1995;18:127–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01857865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mukamal KJ, Chung H, Jenny NS, Kuller LH, Longstreth WT, et al. Alcohol use and risk of ischemic stroke among older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Stroke. 2005;36:1830–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177587.76846.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cox JL. Smoking cessation in the elderly patient. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14:423–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mamun AA, Peeters A, Barendregt J, Willekens F, Nusselder W, Bonneux L NEDCOM, The Netherlands Epidermiology and Demography Compression of Morbidity Research Group. Smoking decreases the duration of life lived with and without cardiovascular disease: a life course analysis of the Framingham Heart Study. Euro Heart J. 2004;25:409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 populations) Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Adams WL, Yuan Z, Barboriak JJ, Rimm AA. Alcohol-related hospitalizations in elderly people: prevalence and geographic variation in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:1222–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gramenzi A, Caputo F, Biselli M, Kuria F, Loggi E, et al. Review article: alcoholic liver disease – pathophysiological aspects and risk factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1151–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): DHHS; 1999. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. Available from URL: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/ResourceMetadata/NNBBHS. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Victor M, Adams RD, Collns GH. The Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome and Related Neurologic Disorders due to Alcoholism and Malnutrition. Vol. 30. Philadelphia (PA): FA Davis Company; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zuccala G, Onder G, Pedone C, Cesari M, Landi F, et al. Dose-related impact of alcohol consumption on cognitive function in advanced age: results of a multicenter survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1743–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Peters R, Peters J, Warner J, Beckett N, Bulpitt C. Alcohol, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2008;37:505–12. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Blow FC. Substance Abuse among Older Adults: Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Rockville (MD): USDHSS/PHS/SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; Jun, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Simoni-Wastila L, Yang HK. Psychoactive drug abuse in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:380–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:30–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.King-Kallimanis B, Gum AM, Kohn R. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders for older Americans in the national comorbidity survey-replication. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:782–92. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ad4d17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pedersen T. Depression, anxiety ups addiction among older. [Accessed 2 July 2013];Americans Psych Central. 2012 Apr 18; Available from URL: http://psychcentral.com/news/2012/04/18/depression-anxiety-ups-addiction-among-older-americans/37483.html.

- 134.National Institute of Mental Health Online. NIH Senior Health. [Accessed 2 July 2013];About anxiety disorders: anxiety disorders in older adults. 2010 Available from URL: http://nihseniorhealth.gov/anxietydisorders/toc.html.

- 135.Blow FC, Brockmann LM, Barry KL. Role of alcohol in late-life suicide. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, RTI International. The NSDUH report: illicit drug use among older adults. Rockville (MD): Center for Behavioral Health Statistics Quality and SAMHSA; Sep 1, 2011. [Accessed 4 February 2014]. Available from URL: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k11/WEB_SR_013/WEB_SR_013_HTML.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]