Abstract

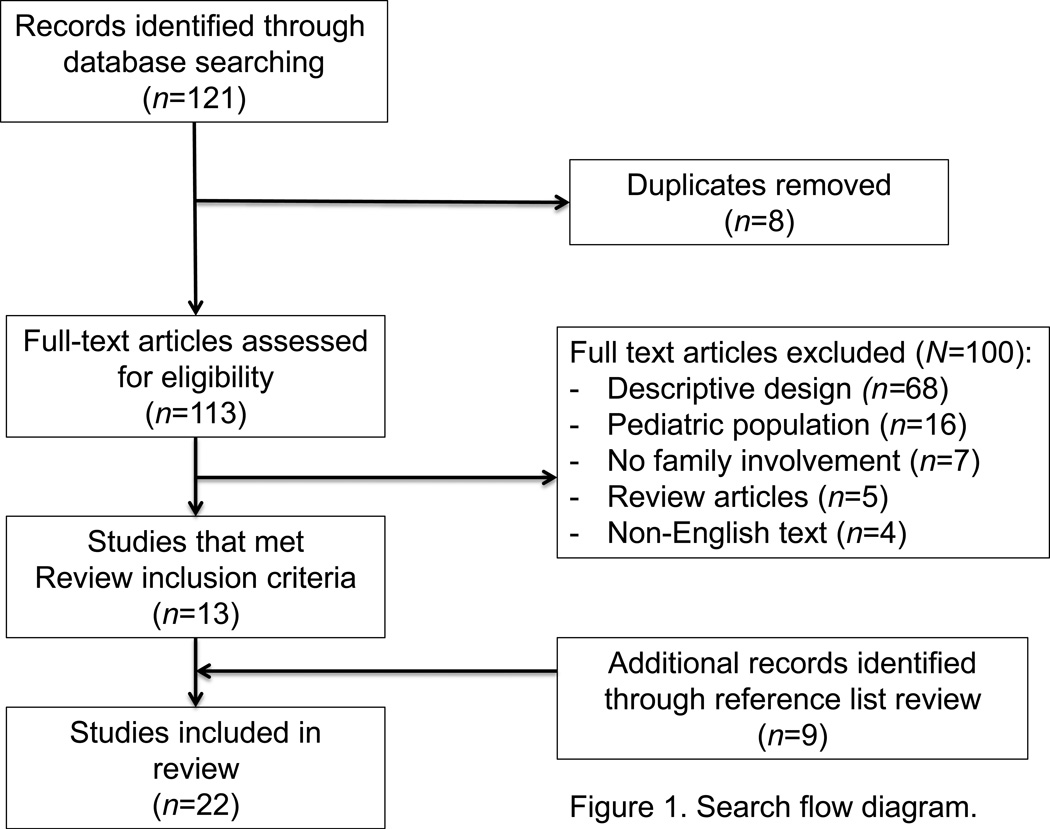

Determining effective decision support strategies that enhance quality of end-of-life decision-making in the intensive care unit is a research priority. This systematic review identified interventional studies describing the effectiveness of decision support interventions administered to critically ill patients or their surrogate decision-makers. We conducted a systematic literature search using PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane. Our search returned 121 articles, 22 of which met the inclusion criteria. The search generated studies with significant heterogeneity in the types of interventions evaluated and varied patient and surrogate decision-maker outcomes, which limited the comparability of the studies. Few studies demonstrated significant improvements in the primary outcomes. In conclusion, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of end-of-life decision support for critically ill patients and their surrogate decision makers. Additional research is needed to develop and evaluate innovative decision support interventions for end-of-life decision-making in the intensive care unit.

Keywords: end of life, decision-making, intensive care unit, critically ill adults, critical care, surrogate decision makers, intervention

For many Americans, an admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) marks the advancement of a chronic condition and the need for end-of-life decision-making. Although an increasing number of Americans wish to die at home, one out of five Americans die while receiving life-sustaining care in an ICU (Curtis, Engelberg, Bensink, & Ramsey, 2012; Institute of Medicine, 2015; Kahn et al., 2015). The ICU has progressively become the apex of life-sustaining and end-of-life care. However, patients, their families, and critical care clinicians have a limited evidence base on how to effectively provide decision support to critically ill patients and their families faced with end-of-life healthcare decisions.

State of Science: End-of-Life Decision-Making in the ICU

With such a high occurrence of cognitive impairment and grim outcomes that preclude the critically ill patient from participating in their own healthcare decisions, the onus of healthcare decision-making often falls on the patient’s family or close friends. These individuals are commonly referred to as surrogate decision makers (SDMs). However, serving as an SDM can prove difficult for several reasons. First, prior studies show that the elicitation of preferences through advance directives is a barrier to end-of-life decision making because only 10% of patients admitted to the ICU possess advance directives (Tillyard, 2007). In addition, recent data indicates that approximately 70% of community-dwelling adults possess advance directives, but their effectiveness in promoting shared decision-making is questionable (Silveira, Kim, & Langa, 2010). Nevertheless, when patient preferences are known, the process of making these critical decisions is profoundly burdensome on the SDM; surrogates require a high degree of emotional and informational support (Braun, Beyth, Ford, & McCullough, 2008; Nelson, Kinjo, Meier, Ahmad, & Morrison, 2005; Wendler & Rid, 2011). To feel supported, SDMs need to believe the patient is receiving appropriate care, see the patient on a regular basis, and receive frequent, honest updates from the patient care providers (Jacob et al., 2016; Obringer, Hilgenberg, & Booker, 2012).

Making healthcare decisions for a decisionally impaired, critically ill patient can have long-standing consequences for SDMs and patients, especially when the SDMs’ decisional needs are unmet. SDMs are asked to make complex, preference-based healthcare decisions which often evokes strong feelings of uncertainty, regret, stress, guilt, depression, and anxiety that linger for months after the patient’s hospitalization or death (Azoulay et al., 2005; Hickman, Daly, & Lee, 2012; Hickman & Douglas, 2011; McAdam, Fontaine, White, Dracup, & Puntillo, 2012; Petrinec, Mazanec, Burant, Hoffer, & Daly, 2015; Wendler & Rid, 2011). In addition, the transition of SDMs to a family caregiver role can yield negative consequences for their physical and mental health, as this new delineation as a family caregiver and its functions demonstrate a profound burden (Schulz & Sherwood, 2008). Furthermore, when the emotional and decisional needs of SDMs are not sufficiently met, SDMs are likely to experience heightened states of psychological morbidity and poor quality of decision making that predispose patients and their SDMs to health care that is inconsistent with their values and preferences (Institute of Medicine, 2015).

To facilitate shared decision-making and assist SDMs with the formulation of complex healthcare decisions, scientists and clinicians have spent the last two decades developing decision support interventions. Decision support is defined as a process that prepares individuals and promotes an environment that facilitates informed decision-making (Murray, Miller, Fiset, O’Connor, & Jacobsen, 2004; O’Connor et al., 1998). Often, decision support is provided in the form of decision aids, which are “defined as interventions designed to help people make specific and deliberative choices among options (including the status quo) by providing (at the minimum) information on the options and outcomes relevant to a person’s health status” (O’Connor, Bennett, & Stacey, 2009). Thus, decision aids can serve as a promising method to provide decision support to SDMs who are faced with authorizing decisions related to life-sustaining preferences. Per White (2011), to optimize decision-making amongst SDMs, the clinical team must be effective communicators, accepting, supportive, and embedded in a system that promotes prompt and consistent multi-disciplinary communication. Furthermore, White (2011) describes the ideal SDM as an individual who can regulate his or her emotions and comprehend the medical situation appropriately to authorize decisions that align with the patient’s values. Past decision support interventions have modified the healthcare team and/or process of providing decision support; however, these studies report mixed outcomes, failing to consistently provide benefit to patients and/or families. (Azoulay et al., 2002; Burns et al., 2003; Connors et al., 1995; Daly et al., 2010; Lilly et al., 2000).

In response to reviews of the extant literature by Scheunemann and McDevitt (2011) and Nelson, Bassett, Boss, and Brasel (2010), Aslakson, Cheng, and colleagues (2014) provided a rigorous systematic examination of palliative care interventions within the ICU. In their publication, Aslakson, Cheng, and colleagues (2014) conceptualize palliative care as the provision of patient and family-centered care that focuses on the anticipation and alleviation of suffering, which is a definition consistent with the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (2004). In the ICU, palliative care is recognized as an essential component of ICU care, regardless of diagnosis or prognosis (Aslakson, Curtis, & Nelson, 2014; Nelson et al., 2011). Although palliative care is often a component of end-of-life care within the ICU, the reverse is not always the case. Furthermore, a recent statement from the Task Force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine highlights the unique challenges posed by the geographical, societal, and cultural differences regarding end-of-life care around the world and encourages relevant stakeholders and thought-leaders to “develop national guidelines and recommendations within each country” (Myburgh et al., 2016). Therefore, a focused systematic review of existing decision support interventions designed for ICU patients and their family members is warranted.

Purpose

Thus, the purpose of this article is to present a synthesis of the theoretical and methodological attributes of decision support interventions targeting SDMs of the critically ill at the end of life. The results of this systematic review of the literature are intended to inform the conceptualization of future decision support interventions and clinical trials in this field of science.

Methods

Design

This study is designed as a systematic review of the relevant literature on end-of-life decision support interventions for critically ill adult patients and their surrogate decision makers. The study eligibility criteria, search strategy, and data extraction plan were determined a priori. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was used as a template in the organization of this systematic review (Liberati, Altman, & Tetzlaff, 2009).

Study Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Studies that were included in this systematic review: (1) included subjects (e.g., critically ill adult patients (aged >18 years) or surrogate decision makers), (2) had a quasi-experimental or experimental design, and (3) evaluated an end-of-life decision support intervention to improve outcomes of critically ill patients or their surrogate decision makers. We defined end-of-life decision support interventions as any information, communication, or psychological support interventions delivered to patients or their surrogate decision makers aimed to improve the quality of their decision-making while in the ICU.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were excluded from this review: (1) were systematic reviews or had a qualitative or descriptive research design, (2) did not involve critically ill adults or their surrogate decision makers, (3) were not published in English, or (4) not available as a full-text publication.

Search Strategy

This review of the literature sought to identify evidence-based interventions that related to the execution or support of decision-making in the ICU. A methodical search was conducted in December 2015 of the following databases: PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Cochrane Library. Using a consistently comprehensive search strategy, the terms “intensive care unit,” “adult,” and “decision-making” were mapped toward their respective Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and CINAHL heading; furthermore, for the PubMed and CINAHL databases, the root “interven” was truncated and included within the database search with the Boolean operator “AND.” Within the Cochrane Library, the MeSH phrases “decision-making” and “intensive care units” were searched. Our search of the Cochrane databases did not yield any relevant reviews. Our search strategy did not initially limit articles by language, geographic location, publication type, or publication date to ensure a thorough representation of the extant literature. An ancillary hand search of the initial articles’ reference lists included within the final review and secondary reference lists of prospectively discovered articles was completed to minimize selection bias and yield a thorough query of the relevant articles.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Author Pignatiello conducted the initial query of the research databases. Ancillary reference and abstract reviews of primary articles were then conducted by Pignatiello, Hickman, and Hetland to ensure a thorough, unbiased representation within the finalized manuscript list.

Results

Search Results

Our search strategy (Figure 1) yielded 121 studies: 105 (87%) studies were extracted from PubMed and 16 (13%) were recovered from the CINAHL. Of the 16 studies generated from the CINAHL, eight were duplicates from the original PubMed query. Of the 113 available manuscripts, 13 met our initial inclusion criteria. In addition to the 13 primary studies identified within the initial query, nine additional manuscripts were identified through title and abstract screening of primary article reference lists as eligible studies for this review. In total, 22 publications met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. One study (Connors et al., 1995) yielded multiple publications subanalyzing the data set; however, only the primary publication summarizing the overall discoveries of the study was included within this review.

Figure 1.

Search flow diagram

Of the 100 excluded manuscripts from our primary literature search, 68 (68%) were excluded due to lack of experimental design; of these 68, five implemented a qualitative research design (7%) and three (4%) implemented a retrospective design. The remaining 16 (16%) were studies involving pediatric populations, seven did not address family decision support or use a decision support intervention (7%), five (5%) were review articles, and four (4%) were non-English publications.

Risk of bias assessment

Consistent with parameters relevant to the conduct of a systematic review, a risk of bias assessment was performed for the included studies. Using guidelines discussed within the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention, the authors (Pignatiello, Hickman) evaluated each of the included studies and report the risks of bias within each study in Table 3 (Higgins & Green, 2011).

Table 3.

Assessment of bias of included studies (N=22)

| Study | Random Sequence Generation (Selection Bias) |

Allocation Concealment (Selection Bias) |

Participant Blinding (Detection Bias) |

Assessor Blinding (Detection Bias) |

Incomplete Outcome Data (Attrition Bias) |

Selective Reporting (Reporting Bias) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahrens, Yancey, & Kollef (2003) | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Azoulay et al. (2002) | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Burns et al. (2003) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Unclear Risk | High Risk | Low Risk |

| Campbell & Guzman (2003) | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Char, Evans, Malvar, & White (2010) | Low Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Connors et al. (1995) | Low Risk | High Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | Low Risk |

| Cox et al. (2012) | High Risk | High Risk | High Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Daly et al. (2010) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | Low Risk |

| Dowdy, Robertson, & Bander (1998) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Dowling & Wang (2005) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Unclear Risk | Low Risk |

| Hatler, Grove, Strickland, Barron, & White (2012) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Kaufer, Murphy, Barker, & Mosenthal (2008) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Kodali et al. (2014) | High risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Lamba, Murphy, McVicker, Harris Smith, & Mosenthal (2012) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Lautrette et al. (2007) | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | Low Risk |

| Lilly et al. (2000) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| McCannon et al. (2012) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Mosenthal et al. (2008) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | High Risk | Low Risk |

| Norton et al. (2007) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Schneiderman et al. (2003) | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Shelton, Moore, Socaris, Gao, & Dowling (2010) | High Risk | High Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Wilson et al. (2015) | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

Note. This table presents risk of bias assessments utilizing the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Green, 2011).

Description of End-of-Life Decision Support Interventions

Research design

The studies included in this review (Table 1) were heterogeneous in design. Six studies were randomized prospective studies (Azoulay et al., 2002; Char, Evans, Malvar, & White, 2010; Connors et al., 1995; Lautrette et al., 2007; Schneiderman et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2015). Connors et al. (1995) conducted a two-phase study: Phase 1 was a prospective observational study, whereas Phase 2 was a cluster randomized controlled clinical trial. The remaining 16 studies were quasi-experimental and included study designs such as comparative cohort and single-arm interventional. No studies incorporated blinding of involved personnel or outcome evaluators.

Table 1.

Description of study methods

| Study | Intervention | Inclusion Criteria | Study Design, Population, and Follow-Up Period. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahrens, Yancey, & Kollef (2003) | Referral to a “communication team” |

Patients who possessed at least one of the following: 1) AIDS diagnosis with CD4 <40/µL 2) Conditions associated with unacceptable quality of life 3) Imminent demise 4) Lethal condition 5) Mechanical ventilation for more than three days 6) NYHA class IV heart failure (ejection fraction less than 20%) |

Design: Non-randomized, controlled trial; N=151 (Control=108; Intervention=43) Population: One MICU No structured follow up period |

| Azoulay et al. (2002) | Family information leaflet | Anticipated ICU length of stay >48 hours |

Design: Randomized controlled trial; N=175 (Control=87; Intervention=88) Population: 17 M/SICUs, 15 MICUs, and 2 SICUs Follow up: between three and five days after study enrollment. |

| Burns et al. (2003) | Social worker interviewed families and provided feedback to clinical team |

All admitted ICU patients eligible | Design: Non-randomized, controlled trial; N=873 (Control=701; Intervention=172). Population: Four SICUs and three MICUs at four teaching hospitals Follow up: Seven days after study enrollment or ICU discharge |

| Campbell & Guzman (2003) | Proactive support approach to end-of-life care |

Patients with global cerebral ischemia (GCI) after cardiac arrest and/or multiple organ system failure (MOSF) |

Design: Retrospective /Prospective comparative cohort study; N=43 (retrospective=40 (MOSF=22; GCI=18); prospective=41 (MOSF=21; GCI=20)) Population: One MICU Follow up: 24 hours before and after a change in patient code status |

| Char, Evans, Malvar, & White (2010) | Two versions of a simulated physician- family cnd-of-life conference |

Surrogate decision makers with any ICU patient |

Design: Randomized controlled trial; N=169 (Numeric version=83; Qualitative=86) Population: Two M/SICUs, one NICU, and one CICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Connors et al. (1995) | Physicians provided with prognostic reports, patient outcome desires, functional disability reports; nurses served as liaison between families and physicians to elicit preferences, improve understanding, and facilitate advance care planning |

Advanced stage of one or more of following illnesses: 1) Acute respiratory failure 2) Multiple organ system failure with sepsis/malignancy 3) Coma 4) Chronic obstructive lung disease 5) Congestive heart failure 6) Cirrhosis 7) Metastatic colon cancer 8) Non-small cell lung cancer |

Design: Phase 1: Prospective, observational study; N=4301 Phase 2: Cluster, randomized, controlled, clinical trial; N=4804 (control=2152; intervention=2652) Population: ICUs from five medical centers across the United States Follow up: Phase 1 – between days 2 and 7, 6 and 15, and 4 to 10 weeks after patient death Phase II – Prognostic measures: study days 2, 4, 8, 10, 15, and 26 Study nurse measures: study day 3 and continuously until patient death or six months later |

| Cox et al. (2012) | Prolonged mechanical ventilation decision aid |

1) At least 18 years of age 2) Identified as most involved in medical decision making 3) Mechanically ventilated for at least ten days |

Design: Phase 1: Methodological development of decision aid Phase 2: Prospective before/after design N=27 surrogates (before=10; after=17) Population: One Surgical, one trauma, one neurological, one cardiac, and one medical ICU within two academic medical centers Follow up: Within two days after occurrence of family meeting |

| Daly et al. (2010) | Intensive Communication Structure (ICS) |

1) 72 hours MV 2) Lack of decisional capacity OR Glasgow Coma Scale <6 3) Not on MV prior to admission 4) Having an identified surrogate decision maker |

Design: Non-randomized, controlled trial; N=481 (control=135; experimental=346) Population: Two MICU, two SICU, and one NICU from two medical centers within the same city Follow up: At least weekly after initial meeting |

| Dowdy, Robertson, & Bander (1998) | Ethics consultation service | More than 96 hours of MV | Design: Non-randomized, controlled trial; N=99 (baseline=37; control=31; proactive=31) Population: One hospital ICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Dowling & Wang (2005) | Critical Care Family Assistance Program |

Individuals with a family member at study site ICU |

Design: Non-randomized pre/post intervention trial; N=330 Population: Two different hospital ICUs Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Hatler, Grove, Strickland, Barron, & White (2012) | Surrogacy information and decision-making tool and SDM pamphlet for patients/family members |

1) At least 96 hours of MV OR 2) ICU LOS of at least seven days |

Design: Non-randomized, pre/post intervention trial; N=203 (pre- intervention=105; post- intervention=98) Population: One NICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Kaufer, Murphy, Barker, & Mosenthal (2008) | Palliative-care emphasis intervention |

Family of patients who died in the ICU |

Design: Non-randomized pre/post- intervention trial; N=88 (pre- intervention=43; post- intervention=45) Population: One MICU Follow up: 2–16 months after patient death |

| Kodali et al. (2014) | Family communication pathway |

Neurosurgical ICU patients’ next of kin |

Design: Quasi-experimental, pre/post intervention design (pre- intervention=26; post- intervention=86) Population: Unspecified ICU Follow up: 2–6 weeks after patient discharge |

| Lamba, Murphy, McVicker, Harris Smith, & Mosenthal (2012) | Structured palliative care program |

Liver transplant service patients | Design: Prospective, observational, pre/post-study; N=183 (baseline=79; intervention=104; baseline deaths=21, intervention deaths=31) Population: One SICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Lautrette et al. (2007) | Structured end-of-life family conferences and bereavement brochure |

Physician prognosis of patients imminent death |

Design: Randomized controlled trial; N=126 (control=63; intervention=63) Population: One MICU and one SICU Follow up: 90 days after patient death |

| Lilly et al. (2000) | Intensive communication intervention |

All adults admitted to the study ICU |

Design Prospective, non-blinded, change-of-practice intervention; N- 530 (pre-intervention=134; intervention=396) Population: One MICU Follow up: Daily |

| McCannon et al. (2012) | Decision support CPR video |

SDM of patients who were: 1) >50 years old 2) Unable to make medical decisions 3) Likely to survive >24 hours |

Design: Quasi-experimental, pre-post intervention; N=50 (pre- intervention=23; post- intervention=27) Population: One MICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Mosenthal et al. (2008) | Palliative care bundle | All adults admitted to the trauma- SICU |

Design: Prospective, observational, pre/post-study; N=633 (baseline=266; intervention=367) Population: Trauma SICU Follow up: Three days after study enrollment |

| Norton et al. (2007) | Palliative care consultations |

One of following: 1) ICU admission following current hospital stay ≥ 10 days 2) Greater than 80-years-old with at least two life-threatening co- morbidities 3) Active stage IV malignancy 4) Post cardiac arrest 5) Intracerebral hemorrhage requiring mechanical ventilation |

Prospective, pre/post nonequivalent control design; N=191 (usual care=65; intervention=126) Population: One MICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Schneiderman et al. (2003) | Ethics consultation | Identified by nursing rounds as adult patients with a potential for value laden treatment decision conflicts |

Prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial; N=546 (usual care=270; intervention=276) Population: Adult ICUs at seven United States’ hospitals Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Shelton, Moore, Socaris, Gao, & Dowling (2010) | Family support coordinator | Anticipated LOS ≥ 5 days | Quasi-experimental pre/post-test design; N=227 (pre=114; post=113) Population: One SICU Follow up: No structured follow up period |

| Wilson et al. (2015) | Video including a simulated hospital code blue and an explanation of resuscitation preference options |

Patients and/or surrogate decision makers of patients within 48-hours of ICU admission |

Randomized, unblinded trial; N=200 (100 usual care and 100 video group) Population: One MICU Follow up: No structured follow up |

Note. NYHA = New York Heart Association; LOS = length of stay; ICU = intensive care unit; MOSF = multi-organ system failure; GCI= global cerebral ischemia; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; MICU = medical intensive care unit; SICU = surgical intensive care unit; NICU = neurological intensive care unit; CICU = cardiac intensive care unit

Setting

All studies except for Lautrette et al. (2007) were completed within the United States. Seven studies were held within medical ICUs (MICUs), three were held within surgical ICUs (SICU), two studies were held within a neurological ICU (NeuroICU), six studies were held between a combination of MICU, SICU, NeuroICU, and/or cardiac ICU, and five studies did not specify the type of ICU in which the study was held. Thirteen studies were implemented in a single hospital ICU, while the remaining studies were conducted in multiple ICUs; seven of these studies were conducted in at least two different hospital systems.

Study population

Study quality was heterogeneous with respect to participants. Fifteen of the 23 studies had a sample population greater than 100 participants. Age of patients in the study ranged from 39–73 years (Cox et al., 2012; Mosenthal et al., 2008); 34–66% of the patients were male (Kodali et al., 2014; Shelton, Moore, Socaris, Gao, & Dowling, 2010) and ICU length of stay (LOS) ranged from 4–213 days (Campbell & Guzman, 2003; Kodali et al., 2014). Family members’ age ranged from 44–70 years (Cox et al., 2012); 26–77% were female (Azoulay et al., 2002; Lautrette et al., 2007); and these family members were either the spouse (36–50%) or child (25–61%) (Azoulay et al., 2002; Lautrette et al., 2007; McCannon et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2015). The reviewed studies used multiple criteria for eligibility. These criteria included enrolling all patients/family members receiving care in an ICU (Burns et al., 2003; Char et al., 2010; Daly et al., 2010; Kaufer, Murphy, Barker, & Mosenthal, 2006; Kodali et al., 2014; Lamba, Murphy, McVicker, Smith, & Mosenthal, 2012; Lilly et al., 2000; Mosenthal et al., 2008), enrolling subjects who met a established length of time for LOS or mechanical ventilation (Azoulay et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2012; Daly et al., 2010; Dowdy, Robertson, & Bander, 1998; Hatler, Grove, Strickland, Barron, & White, 2012; Norton et al., 2007; Shelton et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2015), or enrolling subjects based on certain diagnostic/prognostic criterion or an established level of patient decisional impairment (Ahrens, Yancey, & Kollef, 2003; Campbell & Guzman, 2003; Connors et al., 1995; Lautrette et al., 2007; McCannon et al., 2012; Schneiderman et al., 2003).

Description of decision support interventions

Similar to the systematic review by Aslakson et al. (2014), interventions in this review were commonly consultative or integrative in design. Consultative studies implemented the direct assistance of a palliative care, ethics, or social work team (Ahrens et al., 2003; Burns et al., 2003; Campbell & Guzman, 2003; Dowdy et al., 1998; Kaufer et al., 2006; Lamba et al., 2012; Norton et al., 2007; Schneiderman et al., 2003). These studies used a set of inclusion criteria that triggered the initiation of consultative services to enhance patient and SDM outcomes. Integrative studies included interventions that target the decision-making processes of critical care clinicians, critically ill patients, and their families (Azoulay et al., 2002; Char et al., 2010; Connors et al., 1995; Cox et al., 2012; Daly et al., 2010; Dowling & Wang, 2005; Kodali et al., 2014; Lautrette et al., 2007; Lilly et al., 2000; McCannon et al., 2012; Shelton et al., 2010). Integrative interventions were commonly emphasized as proactive implementation of communication structures that assist with preference elicitation and SDM inclusion in the decision-making process, which were achieved by the utilization of supportive teams, pamphlets, videos, and care bundles (Table 1).

Results

The following sections describe the evaluated outcomes and associated results of the reviewed studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of study outcome measures and findings

| Study | Measured Outcomes | Significance | Non-Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahrens, Yancey, & Kollef (2003) |

|

|

|

| Azoulay et al. (2002) |

|

|

|

| Burns et al. (2003) |

|

|

|

| Campbell & Guzman (2003) |

|

|

|

| Char, Evans, Malvar, & White (2010) |

|

|

|

| Connors et al. (1995) |

|

None |

|

| Cox et al. (2012) |

|

|

|

| Daly et al. (2010) |

|

|

|

| Dowdy, Robertson, & Bander (1998) |

|

|

|

| Dowling & Wang (2005) |

|

|

|

| Hatler, Grove, Strickland, Barron, & White (2012) |

|

|

|

| Kaufer, Murphy, Barker, & Mosenthal (2008) |

|

|

|

| Kodali et al. (2014) |

|

|

|

| Lamba, Murphy, McVicker, Harris Smith, & Mosenthal (2012) |

|

|

|

| Lautrette et al. (2007) |

|

|

|

| Lilly et al. (2000) |

|

|

|

| McCannon et al. (2012) |

|

|

|

| Mosenthal et al. (2008) |

|

|

|

| Norton et al. (2007) |

|

|

|

| Schneiderman et al. (2003) |

|

|

|

| Shelton, Moore, Socaris, Gao, & Dowling (2010) |

|

|

|

| Wilson et al. (2015) |

|

|

|

Note. LOS = length of stay; ICU = intensive care unit; MOSF = multi-organ system failure; GCI = global cerebral ischemia; DNR = do not resuscitate; CMO = comfort measure orders; CPR = cardio-pulmonary resuscitation; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; TISS = Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System Points; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder

Clinical Outcomes

Length of stay

Of the reviewed interventions, patient length of stay (LOS) was the most consistently evaluated patient outcome, with more than 50% of the studies in the review evaluating LOS as an outcome. Four studies consistently reported statistically significant effects on both hospital and/or ICU LOS; these studies enhanced communication methods (Ahrens et al., 2003; Kodali et al., 2014), provided proactive ethics consultations (Schneiderman et al., 2003), or provided family members with a decision-making tool (Hatler et al., 2012). Four studies reported mixed outcomes regarding hospital and/or ICU LOS, with interventions using proactive support to family members through designated communication structures (Campbell & Guzman, 2003; Lilly et al., 2000), palliative care consultations (Norton et al., 2007), or decision support aids (Cox et al., 2012)—these studies demonstrated both significant and nonsignificant effects. Finally, five studies demonstrated no significant effects on hospital and/or ICU LOS as a result of their interventions, which included interventions that targeted family communication (Connors et al., 1995; Daly et al., 2010; Shelton et al., 2010) and used focused family conferences to elicit patient and family treatment preferences (Lamba et al., 2012; Lautrette et al., 2007).

Mortality

Another commonly reported clinical outcome within our review, patient mortality, was evaluated by 30% of the studies. However, studies that evaluated the influence of their intervention on mortality failed to yield a consistent influence. For example Daly et al.'s (2010) and Lilly et al.'s (2000) “intensive communication structure” resulted in statistically significant decreases in patient mortality for individuals who survived to discharge; however, mortality within both studies was not always associated with the patient’s acuity of illness. Alternatively, communication-based interventions by Ahrens et al., (2003), Connors et al., (1995), and Kodali et al., (2014), as well as Norton et al.'s (2007) and Schneiderman et al.'s (2003) proactive consultation services, failed to result in statistically significant reductions in patient hospital and/or ICU mortality.

Mechanical ventilation days

Though not as commonly evaluated, mechanical ventilation days (MVD) were evaluated in 13% of the studies as a metric associated with family decision-making. The only study to significantly influence length of mechanical ventilation was Schneiderman et al.'s (2003) use of proactive ethics consultations, which decreased length of mechanical ventilation by 1.7 days. Conversely, Daly et al.'s (2010) “intensive communication structure” and decision support aids from Cox et al. (2012) and Hatler et al. (2012) resulted in a statistically nonsignificant influence on patient MVD.

Cost and resource utilization

The influence of decision support interventions on care costs and resource utilization was evaluated by seven studies within our review. Ahrens et al.'s (2003) proactive communication team reported a statistically significant decrease in hospital variable direct charges per case (~$8,500), hospital variable indirect charges per case (~$2,900), and hospital fixed charges per case (~$3,100). Furthermore, the use of decision support interventions by Cox et al. (2012) and Hatler et al. (2012) decreased hospital costs by $68,000 and $64,000, respectively. Subsequently, patients with multisystem organ failure receiving comfort measures in Campbell & Guzman's (2003) proactive end-of-life support experienced a statistically significant increase in hospital costs. The remaining studies, which used proactive informative services (Connors et al., 1995), ethics consultations (Dowdy et al., 1998), and family support liaisons (Shelton et al., 2010) had a nonsignificant influence on costs of care.

Decisional Outcomes

Treatment decisions

Nearly 45% (10/23) of the studies evaluated treatment decisions. The use of proactive support services, such as a social workers, end-of-life conferences, or ethics consultations, yielded statistically significant effects on the focus of the patient’s care plan, from aggressive medical treatment to medical care primarily focused on symptom management (Burns et al., 2003; Campbell & Guzman, 2003; Dowdy et al., 1998). Alternatively, the use of palliative care for liver transplant patients (Lamba et al., 2012) and end- of-life conferences along with a bereavement brochure (Lautrette et al., 2007), reported a mixed influence of their intervention on the elicitation of treatment preferences and transition to alternative treatment plans within each study, respectively. The remaining interventions, which provided prognostic reports to physicians (Connors et al., 1995), a communication structure (Daly et al., 2010), decision aids (Cox et al., 2012), and educational CPR videos (McCannon et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2015), had no significant influence on the initiation of DNR orders or code status adjustment and/or treatment preferences such as the receipt of a tracheostomy or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube.

Care concordance

Another commonly used method to evaluate treatment outcomes among families of critically ill patients was to evaluate the decisional or prognostic concordance between family members and members of the healthcare team. Notably, the SUPPORT trial (Connors et al., 1995) had no effect on physician knowledge of patient resuscitation preferences; furthermore, the comparison of qualitative and quantitative prognostic reports did not influence family members’ personal prognostic estimates or enhance understanding of the physician’s prognosis, and understanding of physician’s prognosis measurements required the family to hypothesize the assumed chance of survival from the physician’s perspective (Char et al., 2010). However, enhancing communication and providing family members with decision support significantly decreased family/physician nonconsensus days (Lilly et al., 2000) and family/physician discordance related to one-year patient outcomes (Cox et al., 2012).

Intrapersonal Factors

Family comprehension

Approximately 20% of the studies in our review evaluated comprehension as a metric of effectiveness associated with the family decision-making interventions. The use of decision or information pamphlets yielded significant increases in surrogate comprehension of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment regimen (Azoulay et al., 2002; Cox et al., 2012). Similarly, the use of educational videos related to CPR resulted in significant increases in surrogate CPR knowledge (McCannon et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2015). Cox et al., (2012), McCannon et al., (2012) and Wilson et al. (2015) used previously validated and reliable measures of comprehension, whereas, Azoulay et al. (2002) used a comprehension measure they had used in a prior study (Azoulay et al., 2000).

Emotional/cognitive influence

Two of the studies in this review evaluated the influence of their decision support interventions on associated emotional or cognitive outcomes. Family members in Cox et al.'s (2012) prolonged mechanical ventilation decision support intervention reported a statistically significant decrease in a valid and reliable measure of decisional conflict, yet a nonsignificant increase in physician trust. Using reliable and valid measures, family members assigned to the intervention group of Lautrette et al.'s (2007) study reported statistically significant decreases in symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (24%), anxiety (22%), and depression (27%) at 90 days after study enrollment.

Interpersonal Factors

Satisfaction

Approximately 25% of the studies used valid and reliable measures of satisfaction as an associated outcome. The majority of these studies, which used various interventions such as information leaflets (Azoulay et al., 2002), proactive social work consultations (Burns et al., 2003), and focused family communication interventions, had non-significant effect on satisfaction levels (Dowling & Wang, 2005; Kodali et al., 2014). The remaining two studies reported mixed effects of the intervention on satisfaction. A varying percentage of family members exposed to proactive palliative care reported statistically significant higher levels of satisfaction with coordination of care (20%), information comprehension (29%), honesty of information (24%), completeness of information (29%), decision-making inclusion (57%), decision-making process (30%), and amount of health care given to patient (31%) (Kaufer et al., 2006). Similarly, family members in contact with a designated “family support liaison” reported increased satisfaction associated with comprehension, the care the patient received, and the compassion of the ICU team (Shelton et al., 2010).

Communication

Almost one-third of the studies in this review evaluated family members’ perceived level of communication. The interventions yielding a statistically significant influence on communication used proactive communication techniques (Dowdy et al., 1998; Kaufer et al., 2006), enhanced communication through designated family support personnel or the use of conferences (Dowling & Wang, 2005; Lautrette et al., 2007; Shelton et al., 2010), or used a supportive decision aid (Cox et al., 2012). Alternatively, Wilson et al.'s (2015) video simulation intervention had no influence on the patient or family’s desire to discuss the patient’s code status and Kodali et al.'s (2014) “family communication pathway” was not associated with an increase in family conference occurrence. However, comparison among the differences in communication is limited by the inconsistent use of valid and reliable measures across studies.

Discussion

This systematic review of the literature provides a focused synopsis of clinical trials that offer decision support interventions to family members of critically ill patients. The authors have identified 22 decision support interventions designed for family members making end-of-life decisions for a critically ill patient. Based on the published data from these 22 clinical trials, three main areas for future improvement in this domain of scientific inquiry have been recognized: (a) improve scientific rigor and decrease heterogeneity of study design, (b) use theoretical frameworks to guide intervention development and evaluation, and (c) develop a consensus on a standardized set of patient and family outcomes sensitive to the effects of decision support interventions delivered in this context.

The findings of this study identified a salient theme: a significant lack of homogeneity in the research design and methods used to evaluate the effectiveness of decision support interventions targeting family members of the critically ill. Heterogeneity in study design and outcomes makes study comparison difficult. Overall, the rigor of design within the reviewed studies was weak, as only six studies (Azoulay et al., 2002; Char et al., 2010; Connors et al., 1995; Lautrette et al., 2007; Schneiderman et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2015) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The remaining study designs ranged from retrospective comparative cohort design to nonrandomized controlled trials. However, it is important to note that the use of controlled trials in such a high-stake situation, such as a decision about end-of-life care, might be considered unethical, as individuals could potentially benefit from receiving a decision support intervention.

Of the few RCTs, measured outcomes were inconsistent; the six studies evaluated numerous outcomes, which included comprehension, family satisfaction, decision concordance, preference elicitation, LOS, resource utilization, family member symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression, mortality, family member knowledge, and communication. In addition to heterogeneity of evaluated outcomes, the inclusion criteria necessary for participation varied substantially across studies. Some studies included family members of all patients in the ICU, whereas other studies were more specific and determined a minimum requirement for length of mechanical ventilation, a specific clinical diagnosis, or used the judgment of a healthcare professional to determine appropriateness for study inclusion. Nevertheless, with the expansive variation of inclusion criteria, study design, and outcome measurements, it is not surprising that the outcomes across studies were inconsistent and heterogeneous.

Furthermore, no studies mentioned the development of its intervention from the use a theoretical framework. Without the use of a theoretical framework, it is difficult to ascertain which components of the intervention contributed to the observed outcomes and understand why particular components of an intervention were effective or ineffective (Glanz & Bishop, 2010) Despite the limitations demonstrated by existing decision support interventions for end-of-life decision-making in the ICU, the authors make several recommendations for scientists and healthcare providers providing end-of-life decision support interventions to improve outcomes for ICU patients and their family members.

To facilitate and improve study comparisons, clinicians and scientists would benefit from using similar, if not identical, inclusion criteria for evaluation of their decision support interventions. The majority of the studies in this review included the family members of patients who would be categorized as chronically critically ill (CCI) (Carson, 2012). While not universally defined, chronic critical illness syndrome is commonly identified within individuals who survive the initial insult of acute critical illness, but fail to recover to their pre-illness baseline (Carson & Bach, 2002; Kahn et al., 2015). Outcomes within the CCI are especially poor, with one-year mortality rates commonly exceeding 50% (Wiencek & Winkelman, 2010). Thus, the onset of chronic critical illness often elicits the need to clarify preferences for care at the end of life; however, with the majority of the CCI experiencing persistent cognitive impairment, family members are often required to authorize these end-of-life decisions (T. D. Girard, 2012; Nelson et al., 2006; Pandharipande et al., 2013). Therefore, to proactively support patients and families during such a trying period, Wiencek and Winkelman (2010) recommend identifying patients who require continuous mechanical ventilation for greater than 72 hours, as these patients are at high risk for developing the associated sequelae of chronic critical illness.

To further improve the evaluation of future end-of-life decision support interventions, the authors recommend the use of consistent decision support intervention outcome metrics. According to Murray and colleagues (2004), effective decision support elicits the authorization of a high-quality decision resulting in a high-quality decisional outcome. Therefore, outcomes associated with high decision quality may relate to knowledge, expectations, preference elicitation, decisional conflict, and satisfaction with the decision and decision-making process. Thus, outcomes associated with decision quality may include decision-making self-efficacy, level of distress from the consequences of the decision, decision regret, satisfaction with outcome of the decision, and the appropriate use of resources as a result of the decision (Murray et al., 2004). The consistent use of these outcomes when evaluating the influence of decision support interventions will allow for subsequent improvement and tailoring of interventions to enhance the specific features associated with decision quality and decision outcomes. Moreover, the specification and implementation of theoretical frameworks will enhance the evaluation of future decision support interventions.

Furthermore, aligning with recommendations set forth by a recent report from the Institute of Medicine (2015), end-of-life decision support should be patient and family-centered; thus, future decision support interventions should be tailored to the unique needs of the family members involved. The authors identify a significant dearth in the current state of the science involving end-of-life decision support interventions; they all fail to account for the unique neurocognitive, behavioral, and emotional mechanisms that have been demonstrated to influence decision-making (Dolan, 2002; Evans & Stanovich, 2013; Heatherton, 2011; Lerner, Li, Piercarlo, & Kassam, 2015; Starcke & Brand, 2012). Decision-making in the ICU is complex, eliciting unique cognitive and emotional burdens within the family members involved in this process (Vig, Taylor, Starks, Hopley, & Fryer-Edwards, 2006; Wendler & Rid, 2011). Thus, future end-of-life decision support interventions should evaluate the unique neurocognitive, behavioral, and emotional factors that would directly and indirectly influence the effect of the decision support intervention; furthermore, the authors recommend future interventions should refrain from using a “one size fits all” approach. Instead, clinicians and scientists should develop decision support interventions that are adaptable to the needs of the individual receiving the intervention. When the unique needs of patients and family members are met, outcomes are improved (Obringer et al., 2012).

This review has several limitations. The lack of sample randomization, follow up attrition, outcome blinding that can introduce bias that reflects the authors’ interpretation of the current state of the science. Furthermore, despite the use of key terms in multiple databases and the use of ancillary reference reviews, it is possible that the authors failed to identify key studies evaluating the effects of end-of-life decision support interventions within the ICU. Finally, the review was conducted in December of 2015; therefore, it is possible that the authors failed to include relevant studies that surfaced during the interim period when the review was constructed.

In conclusion, this systematic review of the literature describes the design, methods, and outcomes of clinical trials of end-of-life decision support interventions for patients and family members in the ICU. The results do not indicate a clearly effective way of supporting patients and families during this trying period. Overall heterogeneity of study design and lack of scientific rigor prevented the authors from making a recommendation regarding the type of end-of-life decision support intervention patients and family members should receive within the ICU. However, the authors offer several recommendations to advance the state of the science and outcomes of critically ill patients and their decision makers.

In alignment with recommendations from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), future research in this area should make use of bio-behavioral explanatory paradigms that account for the unique emotional, behavioral, and biological components of decision-making (NINR, 2011). Standardized sets of patient and family outcomes that are sensitive to the effects of decision support interventions; novel research designs, such as multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART); and the recruitment of large and diverse populations of patients and SDMs are needed to advance the science of decision support in the context of end-of-life decision making (Collins, Murphy, & Strecher, 2007). The use of more rigorous study designs, theoretical frameworks, and measures will strengthen the conclusions drawn from future studies (Weldring & Smith, 2013). As the American population continues to age, the need for effective guidance for patients at the end of life and their decision makers is paramount (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). To that end, this systematic review of the literature identifies several key areas for future improvement for end-of-life decision-making in the ICU.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: This publication was made possible by a grant 72118 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), as well as grants NR014213, NR015750 and NR013569 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the RWJF, the NINR, or the NIH.

Contributor Information

Grant Pignatiello, Case Western Reserve University.

Ronald L. Hickman, Jr., Case Western Reserve University.

Breanna Hetland, Case Western Reserve University.

References

- Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: Implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. American Journal of Critical Care. 2003;12(4):317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2014;42(11):2418–2428. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, Galusca D, Smith TJ, Pronovost PJ. Evidence-based palliative care in the intensive care unit: A systematic review of interventions. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014;17(2):219–235. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, Schlemmer B. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Critical Care Medicine. 2000;28(8):3044–3049. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Jourdain M, Bornstain C, Wernet A, Le Gall J-R. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002;165:438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Schlemmer B. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun UK, Beyth RJ, Ford ME, McCullough LB. Voices of African American, Caucasian, and Hispanic surrogates on the burdens of end-of-life decision making. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:267–274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0487-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JP, Mello MM, Studdert DM, Puopolo AL, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Results of a clinical trial on care improvement for the critically ill. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(8):2107–2117. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069732.65524.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123(1):266–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson SS. Definitions and epidemiology of the chronically critically ill. Respiratory Care. 2012;57(6):848–858. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson SS, Bach PB. The epidemiology and costs of chronic critical illness. Critical Care Clinics. 2002;18(3):461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Char SJL, Evans LR, Malvar GL, White DB. A randomized trial of two methods to disclose prognosis to surrogate decision makers in intensive care units. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;182(7):905–909. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Murphy S, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. American Journal of Preventive. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Approaching Death. Institute of Medicine. Vol. 32. Washington DC: The National Academics Press; 2004. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, Fulkerson WJ, Goldman L, Knaus WA, Lynn J, Oye RK. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Hough CL, Kahn JM, White DB, Carson SS. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Critical Care Medicine. 2012;40:2327–2334. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182536a63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Bensink ME, Ramsey SD. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Can we simultaneously increase quality and reduce costs? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;186(7):587–592. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1020CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly BJ, Douglas SL, O’Toole E, Gordon NH, Hejal R, Peerless J, Hickman R. Effectiveness trial of an intensive communication structure for families of long-stay ICU patients. Chest. 2010;138(6):1340–1348. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan RJ. Emotion, cognition, and behavior. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2002;298(5596):1191–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1076358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy MD, Robertson C, Bander JA. A study of proactive ethics consultation for critically and terminally ill patients with extended lengths of stay. Critical Care Medicine. 1998;26(2):252–259. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling J, Wang B. Impact on family satisfaction: The critical care family assistance program. Chest. 2005;128(3 Suppl):76S–80S. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3_suppl.76S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Stanovich KE. Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(3):223–241. doi: 10.1177/1745691612460685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard K, Raffin TA. The chronically critically ill: To save or let die? Respir Care. 1985;30(5):339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard TD. Brain dysfunction in patients with chronic critical illness. Respiratory Care. 2012;57(6):947–957. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatler CW, Grove C, Strickland S, Barron S, White BD. The effect of completing a surrogacy information and decision-making tool upon admission to an intensive care unit on length of stay and charges. Journal of Clinical Ethics. 2012;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF. Neuroscience of self and self-regulation. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62(1):363–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman RL, Daly BJ, Lee E. Decisional conflict and regret: consequences of surrogate decision making for the chronically critically ill. Applied Nursing Research. 2012;25(4):271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman RL, Douglas SL. Impact of chronic critical illness on the psychological outcomes of family members. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2011;21(1):80–91. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c930a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0. London, England: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Retrieved from http://handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. 2015 doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00005. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&q=Dying+in+America%3A+Improving+Quality+and+Honoring+Individual+Preferences+Near+the+End+of+Life&btnG=&as_sdt=1%2C36&as_sdtp=#0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob BM, Horton C, Rance-ashley S, Field T, Patterson R, Johnson C, Frobos C. Needs of patients’ family members in an intensive care unit with continuous visitation. American Journal of Critical Care. 2016;25(2):118–125. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2016258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob DA. Family members’ experiences with decision making for incompetent patients in the ICU: A qualitative study. American Journal of Critical Care. 1998;7(1):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, Cox CE, Hough CL, White DB ProVent Study Group. The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States. Critical Care Medicine. 2015;43(2):282–287. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufer M, Murphy P, Barker K, Mosenthal A. Family satisfaction following the death of a loved one in an inner city MICU. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2008;25(4):318–325. doi: 10.1177/1049909108319262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodali S, Stametz R, Clarke D, Bengier A, Sun H, Layon AJ, Darer J. Implementing family communication pathway in neurosurgical patients in an intensive care unit. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2014;13(4):961–967. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, Harris Smith J, Mosenthal AC. Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant service patients: Structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2012;44(4):508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, Azoulay E. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [Erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 2007 Jul 12;357(2):203] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner J, Li Y, Piercarlo V, Kassam K. Emotion and decision making. Psychology 66. 2015;45(1–3):133–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leske JS. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: A follow-up. Heart Lung. 1986;15(2):189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal. 2009;151(4) doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. W-65-W-94. Retrieved from http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=744698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, Haley KJ, Massaro AF, Wallace RF, Cody S. An intensive communication intervention for the critically Ill. American Journal of Medicine. 2000;109(6):469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam JL, Fontaine DK, White DB, Dracup Ka, Puntillo Ka. Psychological symptoms of family members of high-risk intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Critical Care. 2012;21:386–393. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012582. quiz 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCannon JB, O’Donnell WJ, Thompson BT, El-Jawahri A, Chang Y, Ananian L, Volandes AE. Augmenting communication and decision making in the intensive care unit with a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video decision support tool: A temporal intervention study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15(12):1382–1387. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: A descriptive study. Heart Lung. 1979;8(2):332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, Lavery R, Retano A, Livingston DH. Changing the culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. Journal of Trauma. 2008;64(6):1587–1593. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174f112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MA, Miller T, Fiset V, O’Connor A, Jacobsen MJ. Decision support: helping patients and families to find a balance at the end of life. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2004;10(6):270–277. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.6.13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myburgh J, Abillama F, Chiumello D, Dobb G, Jacobe S, Kleinpell R, Dunstan GR. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Report from the Task Force of World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Journal of Critical Care. 2016;34:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J, Bassett R, Boss R, Brasel K. Models for structuring a clinical initiative to enhance palliative care in the intensive care unit: A report from the IPAL-ICU Project (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU) Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(9):1765–1772. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e8ad23. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3267548/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, Lustbader DR, Mosenthal AC, Mulkerin C The IPAL-ICU Project™. Integrating palliative care in the ICU: The nurse in a leading role. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2011;13(2):89–94. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e318203d9ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JE, Kinjo K, Meier DE, Ahmad K, Morrison RS. When critical illness becomes chronic: Informational needs of patients and families. Journal of Critical Care. 2005;20(1):79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JE, Tandon N, Mercado AF, Camhi SL, Ely EW, Morrison RS. Brain dysfunction: Another burden for the chronically critically ill. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(18):1993–1999. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Nursing Research. NINR bringing science to life – Strategic plan. 2011 Retrieved from https://www.ninr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/ninr-strategic-plan-2011.pdf.

- Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(6):1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM, Bennett C, Stacey D. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. CD001431. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2/full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, Elmslie T, Jolly E, Hollingworth G, Drake E. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: Decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling. 1998;33(3):267–279. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obringer K, Hilgenberg C, Booker K. Needs of adult family members of intensive care unit patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(11–12):1651–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman BJM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: The older population in the United States. Economics and Statistics Administration, US Department of Commerce. 2014;1964:1–28. Retrieved from census.gov. [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. The Kansas. 2004 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.611. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15573672. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Ely EW. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(14):1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrinec AB, Mazanec PM, Burant CJ, Hoffer A, Daly BJ. Coping strategies and posttraumatic stress symptoms in post-icu family decision makers. Critical Care Medicine. 2015;43(6):1205–1212. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheunemann L, McDevitt M. Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: A systematic review. CHEST. 2011;139(3):543–554. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0595. Retrieved from http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/article.aspx?articleid=1087773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, Dugan DO, Blustein J, Cranford R, Young EWD. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Sherwood P. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. The American Journal of Nursing. 2008;108(9 Suppl):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton W, Moore CD, Socaris S, Gao J, Dowling J. The effect of a family support intervention on family satisfaction, length-of-stay, and cost of care in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(5):1315–1320. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d9d9fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(13):1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcke K, Brand M. Decision making under stress: A selective review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36(4):1228–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillyard ARJ. Ethics review: “Living wills” and intensive care--An overview of the American experience. Critical Care (London, England) 2007;11(4):219. doi: 10.1186/cc5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Beyond substituted judgment: How surrogates navigate end-of-life decision-making. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54(11):1688–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldring T, Smith SMS. Patient-Reported Outcomes (pROs) and patient-Reported Outcome Measures (pROMs) Health Services Insights. 2013;6:61–68. doi: 10.4137/HSI.S11093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: The effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154(5):336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DB. Rethinking interventions to improve surrogate decision making in intensive care units. American Journal of Critical Care. 2011;20(3):252–257. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiencek C, Winkelman C. Chronic critical illness: Prevalence, profile, and pathophysiology. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2010;21(1):44–61. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c6a162. quiz 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ME, Krupa A, Hinds RF, Litell JM, Swetz KM, Akhoundi A, Kashani K. A video to improve patient and surrogate understanding of cardiopulmonary resuscitation choices in the icu: A randomized controlled trial. Critical Care Medicine. 2015;43(3):621–629. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]