Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to examine the association between levels of past and current alcohol consumption and all-cause and liver-related mortality among people living with HIV (PLWH).

Methods

A prospective cohort study of 1855 PLWH in Baltimore, MD was carried out from 2000 to 2013. We ascertained alcohol use by (1) self-report (SR) through a computer-assisted self interview, and (2) medical record abstraction of provider-documented (PD) alcohol use. SR alcohol consumption was categorized as heavy (men: > 4 drinks/day or > 14 drinks/week; women: > 3 drinks/day or > 7 drinks/week), moderate (any alcohol consumption less than heavy), and none. We calculated the cumulative incidence of liver-related mortality and fitted adjusted cause-specific regression models to account for competing risks.

Results

All-cause and liver-related mortality rates (MRs) were 43.0 and 7.2 per 1000 person-years (PY), respectively. All-cause mortality was highest among SR nondrinkers with PD recent (< 6 months) heavy drinking (MR = 85.4 deaths/1000 PY) and lowest among SR moderate drinkers with no PD history of heavy drinking (MR = 23.0 deaths/1000 PY). Compared with SR moderate drinkers with no PD history of heavy drinking, SR nondrinkers and moderate drinkers with PD recent heavy drinking had higher liver-related mortality [hazard ratio (HR) = 7.28 and 3.52, respectively]. However, SR nondrinkers and moderate drinkers with a PD drinking history of > 6 months ago showed similar rates of liver-related mortality (HR = 1.06 and 2.00, respectively).

Conclusions

Any heavy alcohol consumption was associated with all-cause mortality among HIV-infected individuals, while only recent heavy consumption was associated with liver-related mortality. Because mortality risk among nondrinkers varies substantially by drinking history, current consumption alone is insufficient to assess risk.

Keywords: alcohol consumption, all-cause mortality, HIV, liver-related mortality

Background

Alcohol use is prevalent among individuals living with HIV, and is associated with decreased medication adherence and lower viral suppression [1,2]. It is also associated with accelerated liver fibrosis among both HIV monoinfected and HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfected individuals [3–5]. Heavy/hazardous alcohol use, often defined in the literature dichotomously as either present or absent, has also been shown to be associated with increased overall [6–10] and liver-related [6,11] mortality among HIV-infected populations.

Although data support an overall increase in mortality among individuals with heavy/hazardous alcohol use, there are fewer studies on how past alcohol consumption or current moderate consumption affect overall and liver-related mortality among persons living with HIV (PLWH). Furthermore, among PLWH, it is unknown whether the relationship between alcohol use and overall and cause-specific mortality is U-shaped, as in the general population [12], or if the relationships differ. Finally, prior studies of liver-related mortality have not accounted for competing causes of death. To further clarify the relationship between alcohol consumption and liver-related mortality, we must account for the possibility of dying from other causes, which can be addressed using competing risk methodology.

Given the current state of the literature on alcohol use and overall and liver-related mortality, we examined the relationships between current and past alcohol use and (1) all-cause mortality and (2) liver-related mortality. We hypothesized that heavy alcohol use would be associated with an increase in both all-cause mortality and liver-related mortality. We used a competing risks analysis strategy to properly quantify the risk of mortality associated with moderate and heavy alcohol consumption.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a prospective cohort study of HIV-infected adults enrolled in the Johns Hopkins HIV Clinical Cohort (JHHCC). The JHHCC is a longitudinal cohort of PLWH receiving care in the Johns Hopkins HIV Clinic. Data are abstracted by trained staff at 6-month intervals and include demographic, clinical, and pharmacy data. Laboratory data are obtained electronically. A description of the data collection methods for the JHHCC has been published elsewhere [13].

In July 2000, an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) collecting patient-reported outcomes was added to the data collection procedures of the JHHCC [2]. The survey queries alcohol use, illicit drug use, cigarette use, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy over the prior 6 months. Written informed consent is obtained to enroll participants. The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included all individuals enrolling in the Johns Hopkins HIV Cohort between July 2000 and August 2012. All study participants with at least one ACASI subsequent to or within 1 year prior to their first medical record abstraction of alcohol use [median time between medical record abstraction and ACASI = 364 days; interquartile range (IQR) 204–731 days] were included in the study (n = 1904). Participants with missing baseline covariate information were excluded from the analysis. The final study sample included 1855 individuals.

Outcome variable

The primary outcome of interest was liver-related death, with competing outcomes defined as death from any other cause. Date of death was ascertained using the National Death Index (NDI) and the Social Security Death Index. Cause of death was obtained from autopsy reports and the NDI. Other sources of cause of death included medical record abstraction and provider report. Liver-related mortality was defined as a diagnosis of “chronic liver disease”, “cirrhosis”, “end-stage liver disease”, “oesophageal varices”, “viral hepatitis (including chronic hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis B)”, “malignant neoplasm of the liver”, “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “hepatic failure”, “hepatorenal syndrome”, “hepatic coma”, “hepatic encephalopathy”, “alcoholic liver disease”, and “portal hypertension” documented as the primary cause or one of the underlying causes of death in the documents above.

Ascertainment and categorization of alcohol use

We ascertained alcohol use by two methods: self-report on an ACASI and medical record abstraction of the participant's first clinic visit. On the ACASI, participants self-reported the average number of drinks consumed per typical drinking day and the number of days alcohol was consumed in a typical week over the past 6 months. Individuals’ drinking status was categorized using the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) definition for heavy/hazardous drinking: > 4 drinks per day or > 14 drinks per week for men and > 3 drinks per day or > 7 drinks per week for women [14]. Individuals consuming any alcohol less than this were classified as moderate drinkers, and those who reported no drinking were categorized as nondrinkers. This variable determined the self-reported current consumption measure used in the analysis.

As the second component of the alcohol categorization, we used data abstracted from the medical record by trained abstractors. As described previously [10], medical providers completed a standard history and physical form at each participant's first clinic visit. Trained coders then abstracted baseline alcohol use. Current alcohol use was defined as provider documentation of any use within the 6 months prior to clinic enrolment; past use was defined as use more than 6 months prior to enrolment but none in the past 6 months. Current alcohol use was then categorized as occasional or heavy. Heavy/hazardous drinking included quantities of > 3 or 4 drinks (for women and men, respectively) per occasion, or daily drinking of > 1 drink per day for women or > 2 drinks per day for men [14]. Based on medical record abstraction, drinking was categorized as: no history of heavy drinking, history of drinking > 6 months ago, or history of heavy drinking within the past 6 months. We did not create an occasional category, as this was not documented frequently by providers.

The combination of self-reported alcohol consumption and provider documentation of heavy drinking were used as the primary exposure for the analysis. We classified the exposure into seven categories: (1) self-reported non-drinker with documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months; (2) self-reported nondrinker with documented past drinking; (3) self-reported nondrinker with no history of heavy drinking; (4) self-reported moderate drinker with documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months; (5) self-reported moderate drinker with documented past drinking; (6) self-reported moderate drinker with no history of heavy drinking; (7) self-reported heavy drinker. All self-reported heavy drinkers were grouped into the same category without regard to provider documentation of drinking status.

Covariates

All covariates included in the analysis were measured at study baseline, defined as the date of clinic entry. Age was treated as a continuous variable modelled using cubic splines with two knots located at the 18th and 78th percentiles. Dichotomous covariates (abstracted from the medical record or from laboratory studies) included diabetes, HCV coinfection, antiretroviral therapy use, and viral suppression (HIV RNA ≤ 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL). Categorical variables included: sex [female, male men who have sex with men (MSM) or male non-MSM]; race (white, black or other); HIV risk factor status [injecting drug use (IDU), MSM, high-risk heterosexual or none]; and nadir CD4 count (< 200, 200–349, 350–500 or > 500 cells/mL). Smoking status and illicit drug use were obtained from the ACASI. Smoking status was dichotomous (ever/never) and illicit drug use was categorized as never, former or current.

Survival analysis structure

We conducted a time-to-event analysis with the time origin defined as the time at which individuals entered clinical care within the Johns Hopkins HIV clinic. People were not considered at risk until both the provider alcohol assessment and at least one ACASI had been completed; therefore, late entries were permitted in the analysis. Individuals exited the study upon death (from any cause) or loss to follow-up or were administratively censored on 20 March 2013.

Statistical analysis

The exposure was categorized into seven groups based on a combination of the ACASI self-reported alcohol consumption variable and the provider-documented heavy drinking variable, as described above. To control for potential confounding, inverse probability weights (IPWs) were used, which may be considered a way of multivariate standardization to the total sample [15–17]. IPWs standardize the observed population to a pseudo-population unconfounded by measured covariates by weighting each observation by the inverse of the conditional probability that the individual received the observed treatment. Confounding was addressed through weighting because the large number of confounders and relatively small number of events made it impractical to adjust for all covariates in a regression model. Weights were constructed by regressing the drinking variable on covariates using a multinomial logistic regression model [18]. All exposure and covariate measurements were taken at baseline and did not time-vary.

Crude and IPW-adjusted incidence rates were determined for all-cause mortality, liver-related mortality, and non-liver-related mortality. The incidence rates provide a basic understanding of the hazards and the cause-specific incidence rates may provide further information on the potential impact of competing events [19].

For all cause-mortality, a Cox proportional hazards model was used. We tested the proportionality hazard assumption and found evidence of global deviation from proportionality [20]. However, this deviation was quantitative in nature and not qualitative and therefore the hazard ratios (HRs) may be interpreted as time-averaged. A crude Cox proportional hazards model was fitted to the data with all-cause mortality as the outcome and baseline drinking status as a predictor. The crude model was then adjusted for potential confounders using the inverse probability weights described above. The IPW adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, HCV coinfection, antiretroviral therapy use, viral suppression, HIV risk factor, nadir CD4 count, smoking status and illicit drug use. Robust standard errors were utilized to account for the weights in the model.

Recent recommendations for competing risk methods are to examine both cause-specific HRs for the event and competing events and cumulative incidence functions for all events in order to have a better understanding of the event processes [21–23]. Therefore, cause-specific proportional hazards models were evaluated for both liver-related and non-liver-related causes of death. The cause-specific hazards and HRs may be interpreted as momentary forces acting to push individuals towards the corresponding event (i.e. liver-related mortality or non-liver-related mortality). Both crude models and IPW models were evaluated.

However, because the cause-specific HR may not be interpreted as having a direct relationship to the probability of event, we utilized a nonparametric estimator of the cumulative incidence function [21,22,24]. This provides the probability of the event occurrence as a function of time. The IPWs were used to weight the cumulative incidence functions to adjust for potential confounders. Furthermore, we utilized the subdistribution proportional hazards model to obtain subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) [25]. The SHRs are directly related to the cumulative incidence curves in competing risk analyses [21,23].

Results

The final study sample included 1855 individuals with a median age at clinic entry of 44.0 years (IQR 36.9-50.0 years). The majority of individuals were black (81%) and male (41% male non-MSM and 22% MSM). At clinic entry, 45% reported having hepatitis C, 8% had diabetes, 75% had ever been smokers, and 63% were either current or former users of illicit drugs. The most common HIV risk status was high-risk heterosexual (40%), followed by IDU (35%). Only 55% of individuals were taking antiretroviral therapy and 48% were virally suppressed, which may be explained by the ascertainment of these variables at clinic entry. Nadir CD4 count was < 200 cells/μL for 60% of the study sample. Providers documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months for 19% of the sample, and documented past drinking for 16% of the sample. Fifty-six per cent of individuals were self-reported nondrinkers. Baseline characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics categorized by audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) self-reported alcohol use

|

n (%) at baseline |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1855) | Heavy (n = 183) | Moderate (n = 633) | None (n = 1039) | P-value | |

| Provider-documented drinking [n (%)] | |||||

| Heavy, within 6 months | 354 (19.1) | 81 (44.3) | 130 (20.5) | 143 (13.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Any, > 6 months ago | 302 (16.3) | 14 (7.7) | 72 (11.4) | 216 (20.8) | |

| Never heavy use | 1199 (64.6) | 88 (48.1) | 431 (68.1) | 680 (65.5) | |

| Age [median (IQR)] | 44 (36.9–50.0) | 42.1 (36.0–48.1) | 42.8 (35.5–49.1) | 44.9 (38.1–50.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Race [n (%)] | |||||

| White | 292 (15.7) | 29 (15.9) | 120 (19.0) | 143 (13.8) | 0.1248 |

| Black | 1509 (81.4) | 148 (80.9) | 499 (78.8) | 862 (83.0) | |

| Other | 54 (2.9) | 6 (3.3) | 14 (2.2) | 34 (3.3) | |

| Sex [n (%)] | |||||

| Female | 681 (36.7) | 75 (41.0) | 161 (25.4) | 445 (42.8) | 0.0017 |

| Male, not MSM | 766 (41.3) | 70 (38.3) | 254 (40.1) | 442 (42.5) | |

| Male, MSM | 408 (22.0) | 38 (20.8) | 218 (34.4) | 152 (14.6) | |

| Hepatitis C [n (%)] | |||||

| Yes | 831 (44.8) | 82 (44.8) | 237 (37.4) | 512 (49.3) | 0.0011 |

| No | 1024 (55.2) | 101 (55.2) | 396 (62.6) | 527 (50.7) | |

| Diabetes [n (%)] | |||||

| Yes | 155 (8.4) | 16 (8.7) | 37 (5.9) | 102 (9.8) | 0.069 |

| No | 1700 (91.6) | 167 (91.3) | 596 (94.2) | 937 (90.2) | |

| Smoking status [n (%)] | |||||

| Ever | 1393 (75.1) | 155 (84.7) | 477 (75.4) | 761 (73.2) | 0.0031 |

| Never | 462 (24.9) | 28 (15.3) | 156 (24.6) | 278 (26.8) | |

| Illicit drug use [n (%)] | |||||

| Never | 690 (37.2) | 49 (26.8) | 218 (34.4) | 423 (40.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Former | 748 (40.3) | 63 (34.4) | 212 (33.5) | 473 (45.5) | |

| Current | 417 (22.5) | 71 (38.8) | 203 (32.1) | 143 (13.8) | |

| HIV risk factor [n (%)] | |||||

| IDU | 641 (34.6) | 63 (34.4) | 177 (28.0) | 401 (38.6) | < 0.0001 |

| MSM | 361 (19.5) | 35 (19.1) | 196 (31.0) | 130 (12.5) | |

| High-risk heterosexual | 739 (39.8) | 78 (42.6) | 225 (35.6) | 436 (42.0) | |

| None | 114 (6.2) | 7 (3.8) | 35 (5.5) | 72 (6.9) | |

| HIV medication use [n (%)] | |||||

| Yes | 1020 (55.0) | 69 (37.7) | 365 (57.7) | 586 (56.4) | 0.0012 |

| No | 835 (45.0) | 114 (62.3) | 268 (42.3) | 453 (43.6) | |

| Viral suppression [n (%)] | |||||

| Yes | 889 (47.9) | 55 (30.1) | 319 (50.4) | 515 (49.6) | 0.0005 |

| No | 966 (52.1) | 128 (70.0) | 314 (49.6) | 524 (50.4) | |

| Nadir CD4 count [n (%)] | |||||

| < 200 cells/mL | 1,120 (60.4) | 108 (59.0) | 370 (58.5) | 642 (61.8) | 0.5269 |

| 200-349 cells/mL | 438 (23.6) | 42 (23.0) | 156 (24.6) | 240 (23.1) | |

| 350-499 cells/mL | 163 (8.8) | 19 (10.4) | 54 (8.5) | 90 (8.7) | |

| ≥ 500 cells/mL | 134 (7.2) | 14 (7.7) | 53 (8.4) | 67 (6.5) | |

| Death [n (%)] | |||||

| Total | 304 (16.4) | 37 (20.2) | 71 (11.2) | 196 (18.9) | 0.0788 |

| Liver-related | 48 (2.6) | 8 (4.4) | 13 (2.1) | 27 (2.6) | |

| Non-liver-related | 256 (13.8) | 29 (15.9) | 58 (9.2) | 169 (16.3) | |

| Days between ACASI and enrolment [median (IQR)] | |||||

| 364 (204–731) | 388 (224–736) | 382 (204–778) | 350 (201–716) | 0.4137 | |

IDU, injecting drug use; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men.

All-cause mortality

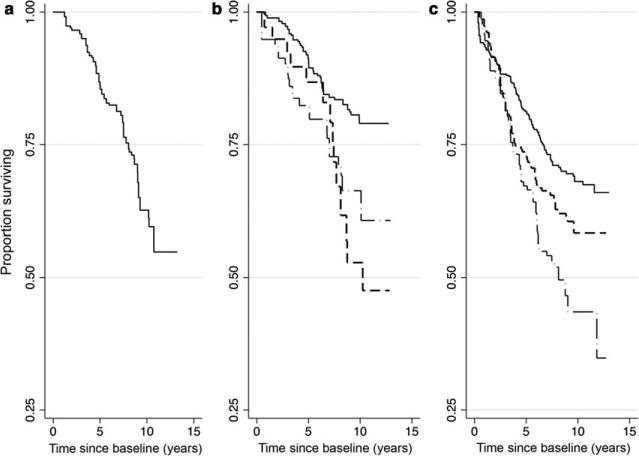

There were 304 deaths observed among the 1855 individuals during the study period. The all-cause mortality rate among the entire study population was 43.0 deaths per 1000 person-years. All-cause mortality was lowest among self-reported moderate drinkers with no history of heavy drinking (23.0 deaths per 1000 person-years) and highest among self-reported nondrinkers with provider-documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months (85.4 deaths per 1000 person-years). Figure 1 displays the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for each exposure category. The seven mortality curves were found to be statistically different based on a log-rank test (P = 0.0001). Table 2 displays the crude and adjusted cumulative mortality rates for each exposure category. Together, these data show a higher mortality rate among those with self-reported heavy drinking and those of all self-reported drinking statuses who had provider-documented drinking.

Fig. 1.

All-cause mortality stratified by self-reported drinking status that has been categorized using the NIAAA definition as heavy drinker (left panel), moderate drinker (middle panel) and nondrinker (right panel). Moderate drinkers and nondrinkers were further split into those with no provider documentation of heavy drinking (solid line), provider-documented drinking > 6 months ago (dashed line), and provider-documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months (dash-dot-dash line).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted all-cause, liver-related, and non-liver-related mortality rates (MRs) per 1000 person-years by alcohol category

| All-cause mortality |

Liver-related mortality |

Non-liver-related mortality |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACASI- reported* |

Medical record abstraction† |

Crude MR (95% CI) | Adjusted MR‡ (95% CI) |

Crude MR (95% CI) |

Adjusted MR‡ (95% CI) | Crude MR (95% CI) |

Adjusted MR‡ |

| Heavy | All responses§ | 43.0 (31.1–59.3) | 44.5 (31.9–63.5) | 9.3 (4.6–18.6) | 10 (4.8–24.3) | 33.7 (23.4–48.4) | 34.4 (23.4–52.5) |

| Moderate | No heavy drinking | 20.5 (14.9–28.3) | 23.0 (16.4–33.1) | 2.8 (1.2–6.7) | 3.4 (1.4–10.6) | 17.7 (12.5–25.1) | 19.7 (13.6–29.4) |

| Moderate | Heavy drinking within past 6 months | 37.4 (24.1–58.0) | 40.8 (26.1–66.5) | 11.2 (5.0–25.0) | 11.5 (5.0–32.2) | 26.2 (15.5–44.2) | 29.3 (17.2–53.5) |

| Moderate | Drinking > 6 months ago | 50.4 (29.8–85.1) | 50.4 (31.2–85.8) | 7.2 (1.8–28.8) | 6.7 (1.4–64.3) | 43.2 (24.5–76.1) | 43.8 (26.0–78.6) |

| None | No heavy drinking | 36.2 (29.9–43.9) | 36.1 (29.8–44.0) | 4.1 (2.4–7.3) | 3.8 (2.2–7.3) | 32.1 (26.2–39.3) | 32.2 (26.3–39.8) |

| None | Heavy drinking within past 6 months | 79.5 (58.3–108.4) | 85.4 (61.1–121.3) | 19.9 (10.7–37.0) | 24.3 (12.7–51.7) | 59.6 (41.7–85.3) | 61.1 (41.9–91.4) |

| None | Drinking > 6 months ago | 56.9 (43.2–74.8) | 59.8 (43.3–84.1) | 5.6 (2.3–13.4) | 3.6 (1.5–11.2) | 51.3 (38.4–68.5) | 56.3 (40.2–80.4) |

CI, confidence interval.

Self-reported alcohol consumption at study entry as reported in the audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI).

Drinking status at study entry as documented in the medical records.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, hepatitis C virus coinfection, antiretroviral therapy use, viral suppression, HIV risk factor, nadir CD4 count, smoking status and illicit drug use through the use of inverse probability weights.

All self-reported hazardous drinkers (as self-reported during ACASI) regardless of the hazardous drinking status recorded in the medical records.

Based on an adjusted Cox proportional hazards model, individuals who reported moderate drinking on the ACASI and had no history of heavy drinking had a statistically significantly lower hazard of mortality compared with all other drinking categories; this group served as the reference group for the model. Compared with this moderate-drinking group, self-reported non-drinkers with provider-documented recent heavy or past drinking had over 2.5 times the hazard for death [HR = 3.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.31–6.12 for those with heavy drinking within the past 6 months; HR = 2.61; 95% CI: 1.62–4.21 for those with past drinking]. Self-reported nondrinkers with no history of heavy drinking had a 50% higher hazard of death (HR = 1.57; 95% CI: 1.05–2.33). Both groups of self-reported moderate drinkers with provider-documented drinking and all self-reported heavy drinkers had approximately twice the hazard of mortality compared with the reference group HR = 1.82 (95% CI: 1.03–3.22) and HR = 2.23 (95% CI: 1.22–4.06) for self-reported moderate drinkers with recent heavy drinking and past drinking, respectively; HR = 1.93 (95% CI: 1.19–3.12) for all self-reported heavy drinkers] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazards of all-cause morality by alcohol category, adjusted*

| ACASI-reported† | Medical record abstraction‡ | HR† | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | No heavy drinking | Ref | ||

| None | No heavy drinking | 1.57 | 1.05–2.33 | 0.027 |

| None | Drinking > 6 months ago | 2.61 | 1.62–4.21 | < 0.001 |

| None | Heavy drinking within past 6 months | 3.76 | 2.31–6.12 | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | Drinking > 6 months ago | 2.23 | 1.22–4.06 | 0.009 |

| Moderate | Heavy drinking within past 6 months | 1.82 | 1.03–3.22 | 0.040 |

| Heavy | All responses§ | 1.93 | 1.19–3.12 | 0.008 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, hepatitis C virus coinfection, antiretroviral therapy use, viral suppression, HIV risk factor, nadir CD4 count, smoking status and illicit drug use.

Self-reported alcohol consumption at study entry as reported in the audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI).

Drinking status at study entry as documented in the medical records.

All self-reported heavy drinkers (as self-reported during ACASI) regardless of the drinking status recorded in the medical records.

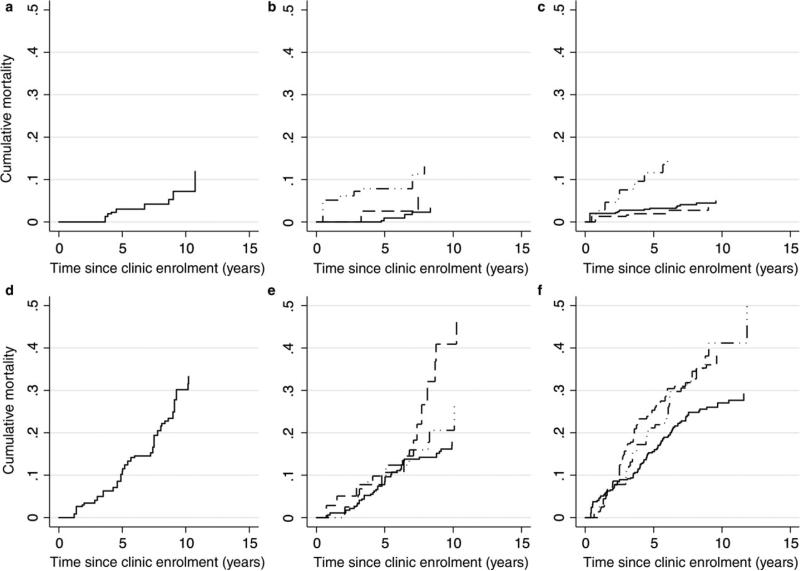

Liver-related mortality

Of the 304 total deaths, 48 were found to be liver-related. The liver-related mortality rate at 13 years post-study enrolment ranged from 3.4 per 1000 person-years (95% CI: 1.4–10.6 per 1000 person-years) among moderate drinkers without a heavy drinking history to 24.3 per 1000 person-years (95% CI: 12.7–51.7 per 1000 person-years) among current nondrinkers with provider-documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months. Incidence rates for all exposure categories are shown in Table 2 and cause-specific HRs from the Cox proportional hazards model are reported in Table 4. Briefly, the Cox model showed the lowest liver-related mortality among current self-reported moderate drinkers with no history of heavy drinking (reference group). The highest hazard for liver-related mortality occurred among current nondrinkers with a recent history of heavy drinking (HR = 7.28; 95% CI: 2.43–21.78). All self-reported heavy drinkers and self-reported moderate drinkers with a recent history of heavy drinking also had an increased hazard of liver-related mortality compared with the reference group (HR = 3.00 and 3.52, respectively). Self-reported moderate drinkers with a history of drinking > 6 months ago, nondrinkers with a history of drinking > 6 months ago and those who never drunk had a similar hazard of liver-related mortality compared with the reference group (HR = 2.00, 1.06 and 1.15, respectively; P > 0.4).

Table 4.

Cause-specific hazards of liver-related and non-liver-related mortality by alcohol category*

| Liver-related mortality |

Non-liver-related mortality |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACASI-reported† | Medical record abstraction‡ | HR† (95% CI) | P-value | HR† (95% CI) | P-value |

| Moderate | No heavy drinking | Ref | Ref | ||

| None | No heavy drinking | 1.15 (0.40–3.33) | 0.794 | 1.64 (1.06–2.52) | 0.025 |

| None | Drinking > 6 months ago | 1.06 (0.30–3.78) | 0.926 | 2.88 (1.73–4.80) | < 0.001 |

| None | Heavy drinking within past 6 months | 7.28 (2.43–21.78) | < 0.001 | 3.15 (1.83–5.42) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | Drinking > 6 months ago | 2.00 (0.38–10.46) | 0.413 | 2.27 (1.18–4.36) | 0.014 |

| Moderate | Heavy drinking within past 6 months | 3.52 (1.04–11.90) | 0.043 | 1.53 (0.79–2.97) | 0.21 |

| Heavy | All responses§ | 3.00 (0.93–9.65) | 0.065 | 1.75 (1.01–3.01) | 0.045 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, hepatitis C virus coinfection, antiretroviral therapy use, viral suppression, HIV risk factor, nadir CD4 count, smoking status and illicit drug use.

Self-reported alcohol consumption at study entry as reported in the audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI).

Drinking status at study entry as documented in the medical records.

All self-reported heavy drinkers (as self-reported during ACASI) regardless of the drinking status recorded in the medical records.

Following a similar trend to the Cox model, the competing risk regression model showed the highest liver-related mortality among individuals with current heavy drinking behaviour (SHR = 2.90; 95% CI: 0.91–9.30 for all self-reported heavy drinkers; SHR = 3.35; 95% CI: 0.99–11.35 for self-reported moderate drinkers with a recent history of heavy drinking; and SHR = 6.29; 95% CI: 2.09–18.96 for self-reported nondrinkers with a recent history of heavy drinking). The subdistribution hazard for liver-related mortality was not significantly increased among moderate drinkers and nondrinkers with a history of drinking > 6 months ago or among nondrinkers with no history of heavy drinking. The cumulative incidences of liver-related and non-liver-related mortality are shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Liver-related (top row) and non-liver-related (bottom row) cumulative mortality by self-reported drinking status that has been categorized using the NIAAA definition as heavy drinker (left panel), moderate drinker (middle panel) and nondrinker (right panel). Moderate drinkers and nondrinkers were further split into those with no provider documentation of heavy drinking (solid line), provider-documented drinking > 6 months ago (dashed line), and provider-documented heavy drinking within the past 6 months (dash-dot-dash line).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of PLWH enrolled in care, we found that heavy alcohol use, captured either by ACASI self-report or through provider documentation, was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality compared with moderate alcohol use. Self-reported or provider-documented heavy alcohol use was associated with increased risk of liver-related mortality compared with moderate alcohol use; however, past use (> 6 months prior to the visit) was not associated with an increased risk of liver-related mortality. These findings suggest that the risk of liver-related mortality may decrease among those who discontinue heavy alcohol use. This has clinical implications for treating individuals who exhibit hazardous drinking behaviour, as the risk of liver-related mortality could approach that of never-hazardous drinkers upon refraining from excess alcohol use.

Our finding that heavy alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality is consistent with findings of DeLorenze et al. [8] Using ICD-9 fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) diagnosis codes for alcohol abuse/dependence, they too found an association between alcohol abuse or dependence and all-cause mortality that persisted after adjusting for the presence of other substance abuse, HIV viral load, and standard demographic factors. DeLorenze et al. examined a population of commercially insured individuals with diagnosed substance use disorders in northern California. Their study population was 90% male and nearly 60% white. Our study extends their findings regarding all-cause mortality to a different study population (approximately 80% black and 60% male) who were exposed to all levels of alcohol use, including moderate use and no alcohol use. We found that moderate alcohol use was associated with a decreased risk for all-cause mortality in the absence of provider-documented heavy use, which is similar to previous findings for the overall population [12]. Because of the detrimental impact of even a moderate level of alcohol consumption on antiretroviral therapy adherence [1], liver fibrosis measured by fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) [4] and other proximal factors, it is important to discuss potential alcohol-associated harms among those with moderate alcohol use.

In addition to examining the association between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality, we had a particular interest in studying liver-related mortality. A recent study by Fuster et al. [26] examined both all-cause and liver-related mortality among PLWH and found that HCV infection was associated with an increase in both all-cause and liver-related mortality. However, their sample was limited to individuals with past and current alcohol problems and focused on the relationship between HCV coinfection and mortality. We extend these findings by examining all-cause and liver-related mortality among PLWH with all levels of alcohol consumption.

We found that the clinical assessment (documentation of heavy drinking in the previous 6 months) was the most significant predictor of liver-related mortality and was more strongly associated with the outcome than current self-reported alcohol consumption. The clinical assessment is most sensitive to severe heavy drinking, as clinicians may neglect to document heavy drinking among individuals whose consumption fluctuates between moderate and heavy [27]. However, it is unlikely that an individual would falsely report current heavy alcohol consumption. Therefore, lack of provider documentation of heavy drinking among those who self-report heavy consumption was probably an oversight rather than a meaningful omission and prompted our decision to combine all self-reported heavy drinkers into one category. Although patient under-reporting of alcohol consumption is likely to persist, providers could encourage greater openness by focusing on nonjudgmental, empathetic interactions such as those promoted in brief intervention approaches, thereby by reducing the stigma associated with self-reporting hazardous alcohol use and increasing the validity of self-reported consumption.

Although previous research has demonstrated an association between heavy alcohol consumption and an increased hazard of liver-related mortality among PLWH [6,11], these studies did not account for the competing nature of cause-specific mortality. In this study, we used a competing risk regression model to estimate the risk of liver-related mortality, accounting for the competing event of non-liver-related mortality. Properly accounting for competing events is important when an exposure is associated with both the event of interest and the competing event, as a standard survival model can provide incorrect inferences with regard to risk in these scenarios. The resulting risk estimates indicate the joint likelihood that an individual died and that the death was liver-related, whereas traditional methods inform us about the hazard of liver-related mortality under the assumption of no competing risks. Using competing risk methodology, we continued to find an increased hazard of mortality among heavy drinkers and former drinkers compared with moderate drinkers with no history of heavy drinking.

The individuals with the worst all-cause mortality were nondrinkers with a provider documentation of heavy drinking within the past 6 months. It is likely that the sickest nondrinkers only became nondrinkers after causing irreversible damage to their health status and died shortly after quitting their heavy drinking behaviour. Conversely, individuals with a history of drinking > 6 months ago did not have a significantly increased risk of liver-related mortality compared with nondrinkers who never drank heavily. This suggests that helping individuals with heavy drinking behaviour to stop drinking could improve liver-related outcomes for high-risk individuals. Finally, it is noteworthy that nondrinkers with no history of heavy drinking had significantly higher all-cause and non-liver-related mortality compared with moderate drinkers. This mirrors the U-shaped effect of alcohol on mortality that has been observed in previous studies [12]. The small number of liver-related deaths in the cohort probably prevented this pattern from being observable for liver-related mortality.

This analysis had several strengths. The longitudinal nature of the clinical cohort allowed for long follow-up, with a mean follow-up time of 4.2 years and a maximum of 12.5 years. The unique exposure categorization capitalized on the availability of both self-reported data and a clinical assessment. Also, the study cohort included both men and women, which allowed us to account for gender differences in the effect of alcohol on liver-related mortality.

There were limitations to this study. The number of liver-related deaths was small, which limited our ability to examine potential interactions within the data. A larger sample size would allow for stratification by hepatitis C status, which was also of interest in this analysis. Additionally, data analysed in this study came from a single clinic within Baltimore, which might not be representative of other urban areas. Finally, there is the potential for biased assessments of provider-documented alcohol use.

In conclusion, we found that any heavy alcohol consumption was associated with all-cause mortality among PLWH, while provider documentation of heavy alcohol use within the past 6 months was associated with liver-related mortality. Additionally, we found that mortality risk among self-reported nondrinkers varied substantially by past drinking history, indicating that self-reported current consumption alone is insufficient to assess mortality risk. Rather, a nuanced categorization of alcohol consumption using both self-report and provider assessment with determination of past and current use provides a more optimal method for examining the effects of alcohol on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [grant nos U24AA020801 (MEM and GC) and RO1AA016893 (GC, RDM and BL)], the National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant no. U01DA036935 (RDM, GC and BL)], and the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases [grant nos P30AI094189 (RDM and BL) and T32AI102623 (CC)].

Footnotes

This work was presented as an abstract at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, February 23, 2016.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucas GM, Gebo K, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Longitudinal assessment of the effects of drug and alcohol abuse on HIV-1 treatment outcomes in an urban clinic. AIDS. 2002;16:767–774. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharya R, Shuhart MC. Hepatitis C and alcohol: interactions, outcomes, and implications. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:242–252. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim JK, Tate JP, Fultz SL, et al. Relationship between alcohol use categories and noninvasive markers of advanced hepatic fibrosis in HIV-infected, chronic hepatitis C virus-infected, and uninfected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1449–1458. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muga R, Sanvisens A, Fuster D, et al. Unhealthy alcohol use, HIV infection and risk of liver fibrosis in drug users with hepatitis C. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonacini M. Alcohol use among patients with HIV infection. Ann Hepatol Off J Mex Assoc Hepatol. 2011;10:502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, Roberts MS, et al. Estimating the impact of alcohol consumption on survival for HIV+ individuals. AIDS Care. 2007;19:459–466. doi: 10.1080/09540120601095734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLorenze GN, Weisner C, Tsai AL, Satre DD, Quesenberry CP. Excess mortality among HIV-infected patients diagnosed with substance use dependence or abuse receiving care in a fully integrated medical care program. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hessol N, Kalinowski A, Benning L, et al. Mortality among participants in the multicenter AIDS cohort study and the women's interagency HIV study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:287–294. doi: 10.1086/510488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neblett RC, Hutton HE, Lau B, McCaul ME, Moore RD, Chander G. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected women: impact on time to antiretroviral therapy and survival. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:279–286. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcellin P, Pequignot F, Delarocque-Astagneau E, et al. Mortality related to chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C in France: evidence for the role of HIV coinfection and alcohol consumption. J Hepatol. 2008;48:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jayasekara H, English DR, Room R, MacInnis RJ. Alcohol consumption over time and risk of death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:1049–1059. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore RD. Understanding the clinical and economic outcomes of hiv therapy: the Johns Hopkins HIV clinical practice cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;17(Suppl. 1):S38–S41. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199801001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide. Vol. 35. Fam Pract News; 2005. p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, Matsuyama Y. Marginal structural models as a tool for standardization. Epidemiology. 2003;14:680–686. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000081989.82616.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernan MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology. 2000;11:561–570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robins J, Hernan M, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole SR, Hernán M a. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:656–664. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grambauer N, Schumacher M, Dettenkofer M, Beyersmann J. Incidence densities in a competing events analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1077–1084. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allignol A, Schumacher M, Wanner C, Drechsler C, Beyersmann J. Understanding competing risks: a simulation point of view. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:244–256. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole SR, Lau B, Eron JJ, et al. Estimation of the standardized risk difference and ratio in a competing risks framework: application to injection drug use and progression to AIDS after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:238–245ss. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine JP, Gray RJ, Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuster D, Cheng DM, Quinn EK, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection is associated with all-cause and liver-related mortality in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with alcohol problems. Addiction. 2014;109:62–70. doi: 10.1111/add.12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinson DC, Turner BJ, Manning BK, Galliher JM. Clinician suspicion of an alcohol problem: an observational study from the AAFP National Research Network. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:53–59. doi: 10.1370/afm.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]