Abstract

Cancer progression is a global burden. The incidence and mortality now reach 30 million deaths per year. Several pathways of cancer are under investigation for the discovery of effective therapeutics. The present study highlights the structural details of the ubiquitin protein ‘Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D4’ (UBE2D4) for the novel lead structure identification in cancer drug discovery process. The evaluation of 3D structure of UBE2D4 was carried out using homology modelling techniques. The optimized structure was validated by standard computational protocols. The active site region of the UBE2D4 was identified using computational tools like CASTp, Q-site Finder and SiteMap. The hydrophobic pocket which is responsible for binding with its natural receptor ubiquitin ligase CHIP (C-terminal of Hsp 70 interacting protein) was identified through protein-protein docking study. Corroborating the results obtained from active site prediction tools and protein-protein docking study, the domain of UBE2D4 which is responsible for cancer cell progression is sorted out for further docking study. Virtual screening with large structural database like CB_Div Set and Asinex BioDesign small molecular structural database was carried out. The obtained new ligand molecules that have shown affinity towards UBE2D4 were considered for ADME prediction studies. The identified new ligand molecules with acceptable parameters of docking, ADME are considered as potent UBE2D4 enzyme inhibitors for cancer therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12154-016-0164-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Active site, ADME, Cancer, Homology modelling, Protein-protein docking, Virtual screening

Introduction

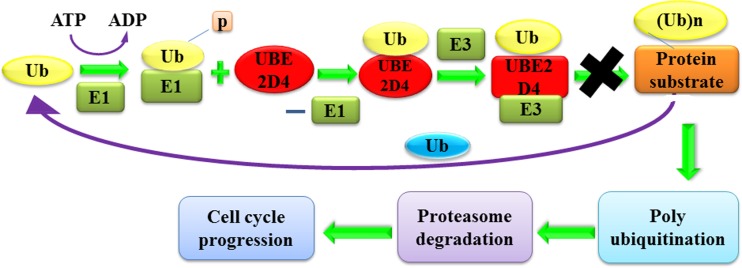

Cancer is a complex disease, which involves uncontrolled cell differentiation and proliferation that lead to death [1, 2]. Cancer is a leading cause of death, accounting for 8.2 million deaths worldwide announced by the WHO. Ubiquitin-proteasome degradation process plays a crucial role in the cell cycle progression and formation of cancer tumours [3, 4]. In the G-phase of cell cycle, the negative regulation of cyclin-dependent kinases, affects the ubiquitination and phosphorylation process that leads to tumour formation [5, 6]. The system of ubiquitin degradation of protein involves covalent attachment with their substrate proteins. The conjugated proteins form a catalytic proteasome complex, i.e. the 26s proteasome [7–9]. The conjugation of ubiquitin to the substrates proceeds via a three-step mechanism. In the initial step, ubiquitin is activated (Fig. 1), in an ATP-consuming reaction, by ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, forming the high energy thioester bond [10, 11]. In the second step, the activated ubiquitin is transferred to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2. Finally, the ubiquitin ligase E3 enzyme catalyses the E2 and transfers the ubiquitin to its natural polyubiquitination reactions and subsequent proteasome degradation [12–14]. In this ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D4 (UBE2D4) or (E2) interacts with the ubiquitin ligase CHIP (C-terminal of Hsp 70 interacting protein) (E3), involved in the polyubiquitination reaction and cell cycle progression [15] (Fig. 1). The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D4 (UBE2D4) is a ubiquitin carrier protein, consisting of 147 amino acid residues. The alternate names of the UBE2D4 enzyme are E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme D4, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme HBUCE1 and the ubiquitin-protein ligase D4. The UBE2D4 binds with the ubiquitin ligase CHIP and is involved in the regulation of the cellular functions and control of the cell cycle activities that promote proliferation in cancer cells [16, 17]. The development of new chemical entities targeting UBE2D4 is a new strategy in the cancer medicinal chemistry research.

Fig. 1.

Bio-chemical pathway of UBE2D4 and its role in cancer progression. Ubiquitin proteasomal degradation process involves binding of ubiquitin with ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) in the presence of ATP to form a thio-ester bond. Activated ubiquitin is transferred to UBE2D4 enzyme maintaining thio-ester bond with the elimination of E1 enzyme. This reaction is followed by covalent attachment of UBE2D4 with an ubiquitin CHIP- ligase (E3) which results in polyubiquitination reaction and leads to cell cycle progression

The present study includes the 3D structural evaluation of UBE2D4, its active site identification and virtual screening at the active site with a huge library of molecules to identify the ligand molecules as its inhibitors. The pharmacokinetic properties of the identified ligand molecules are predicted using in silico techniques. The ligand molecules with acceptable ADME properties may be considered as potential drug candidates for cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Computational methods

All computational analyses were executed on Intel® core™ i5 3rd generation with 8GB RAM running in Windows-based operating system. The software used in virtual screening and docking study is Schrödinger suite software (http://www.schrodinger.com/). All the results were visualized and analysed using Accelrys discovery studio 3.5 (Accelrys Software Inc., 2012 Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer v 3.5. San Diego, CA), PyMOL1.3 (http://www.pymol.org) and Maestro (Maestro v 9.1 Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2012).

Homology modelling of UBE2D4 protein

Template selection and sequence alignment

The 3D structure of the UBE2D4 enzyme is experimentally not reported either in X-ray or NMR studies. The 3D model of the UBE2D4 is generated using homology modelling technique. Homology modelling plays an important role in determining the 3D structure of the proteins with unknown secondary structure [18, 19]. The FASTA sequence of UBE2D4 enzyme is retrieved from the ExPASy/UniProt proteomic server [20, 21]. The amino acid sequence of the UBE2D4 enzyme is subjected to the BLASTp [22, 23], Jpred3 [24] and Domain Fishing [25] server tools, to identify the homologous proteins as a template. The template is identified based on the sequence, secondary structure and domain similarity. The template is selected based on a statistical measurement, e-value [23]. A low e-value indicates high sequence similarity of the target protein with that of the template. The sequence alignment of the UBE2D4 with the template protein is carried out using CLUSTAL W server [26] to identify the structurally conserved regions. In the CLUSTALW server, the Gonnet matrix scoring function is used to refine the alignment using classical distance measurements [27].

Model generation and validation

The three-dimensional (3D) model of the protein is generated using MODELLER 9.11 [28], an automated homology modelling programme. The model is generated using optimization of spatial restraints from the alignment of the protein sequence with the template [29]. Thirty-two initial models of protein are generated using MODELLER 9.11, and the model with the least modeller objective function is considered for the structural refinement studies [30]. The energy minimization of the UBE2D4 3D model is carried out using the Protein Preparation wizard [31] in the Schrödinger suite by OPLS_2005 force field [32, 33]. In the minimization process, the bond orders are assigned, hydrogens are added to all the atoms in the system and the water molecules are removed. The refined and energy minimized UBE2D4 model is validated using PROCHECK [34, 35], ProSA [36, 37] and VERIFY_3D [38, 39] server tools. The model is validated for the stereochemical quality, local model quality and overall model quality. The stereochemical quality of the protein model is evaluated by the phi (Φ) and psi (ψ) angles of amino acids in Ramachandran plot using PROCHECK [40, 41]. The ProSA server is used to assess the quality of the model based on the statistical analysis of all the available protein structures in PDB with the same sequence length [42]. The ProSA server gives the z-score that indicates an overall model quality and ProSA energy profile plot that gives local model quality of the protein. The z-score measures the total energy of the structure with respect to the energy distribution derived from the conformations of its own amino acid sequence number deposited in the PDB. The VERIFY_3D server assesses the quality of the 3D structure of the protein in terms of stereochemistry and energetics by 1D sequence profiling [43]. The protein model compares its own sequence with the 3D environment of atoms from the same protein. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of UBE2D4 structure for super imposition with that of its template is calculated using Swiss PDB viewer (SPDBV_4.1.0) [44]. The secondary structure details of the validated UBE2D4 model are predicted using PDB Sum server and analysed using Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer (Accelrys Software Inc., 2012 Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer v 3.5. San Diego, CA).

Active site prediction

The active site residues of the UBE2D4 protein are identified using CASTp [45], Q-site Finder [46] and SiteMap [47] tools. The protein-protein docking of the UBE2D4 with its natural substrate ubiquitin ligase CHIP is carried out using PatchDock server [48] to identify the binding site region and residues in the UBE2D4 protein. CASTp is used to identify the binding cavities and pockets in the protein structure [49]. The Q-site Finder server identifies the energetically favourable binding sites in the protein structure [50]. The SiteMap module of the Schrödinger suite identifies the potential druggable binding sites in the protein structure and determines the binding site points on the protein surface that are merged into larger sites [51].

Virtual screening and pharmacokinetic properties calculation

Virtual screening is a method applied to identify new chemical entities and structural scaffolds for a protein target [52, 53]. The virtual screening process is carried out in virtual screening work flow of the Schrödinger suite. The virtual screening method involves three consecutive steps, namely (i) receptor grid generation, (ii) ligand preparation and (iii) ligand docking. Considering the active site region, a grid is generated for the protein UBE2D4, at its active site region using the Glide module (Glide, version 5.6, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2010) of the Schrödinger suite for the virtual screening study. The molecular structural databases in SDF (standard data format) file format are retrieved from ChemMine [54] and Asinex Database (www.asinex.com). The small structural ligand molecules are subjected to the LigPrep module [55] (LigPrep, version 5.6, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2010) of the Schrödinger suite for ligand preparation, which is set to generate five stereo isomeric structures per ligand using OPLS_2005 force field. For each ligand, multiple ionization states, tautomers, stereoisomers and five low energy conformers are generated at pH 7.0 ± 2.0. The active site grid and the prepared molecular ligand structures are subjected to the glide module for the ligand and receptor docking [56]. In the Glide module, the ligand molecules are filtered in three hierarchical levels, namely, high throughput virtual screening (HTVS), standard precision (SP) and extra precision (XP) [57] using OPLS_2005 force field. Finally, the ligand molecules are sorted based on the high glide score and glide energy.

Glide score is a glide’s scoring function measured based on the ChemScore. Glide score calculates the ligand binding energy in the 3D complex model. The Glide score was calculated using the following equation:

where H-bond = Hydrogen bonds, Lipo = Hydrophobic interactions, Metal = Metal binding terms, Site = polar binding site, Coul = Coulomb forces, vdW = van der Waals forces, Bury P = Penalty for buried polar groups and Rot Bond = Freezing rotatable bonds.

The glide energy is used to calculate the free energy of binding, for set of ligands to the receptor. The energies of the docked complexes are calculated using OPLS_2005 force filed and generalized-Born/surface area (GB/SA) continuum solvent model. The free energy of binding ΔG is calculated using the following equation:

where E complex, E protein and E ligand are the minimized energies of the protein-ligand docked complex, the protein and the ligand, respectively.

where G solv (Complex), G solv (protein) and G solv (ligand) are the surface area energies of the complex, protein and ligand, respectively.

where G SA (Complex), G SA (protein) and G SA (ligand) are the solvation free energies of the complex, protein and ligand, respectively.

The solvent accessible surface area (SASA) [58] of the protein before and after docking is calculated with default parameters using Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer. The protein-ligand docked structures are analysed and visualized using Accelrys Discovery Studio and PyMoL 1.3 [59]. The pharmacokinetic properties like absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) [60] are calculated using the QikProp [61] (QikProp, version 3.3, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2010) module of the Schrödinger suite.

Results and discussion

UBE2D4 protein modelling and validation

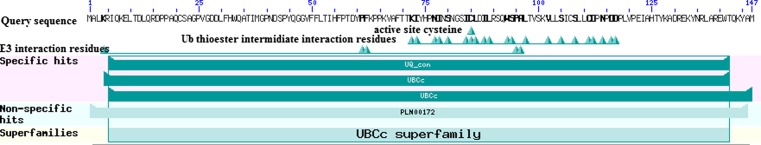

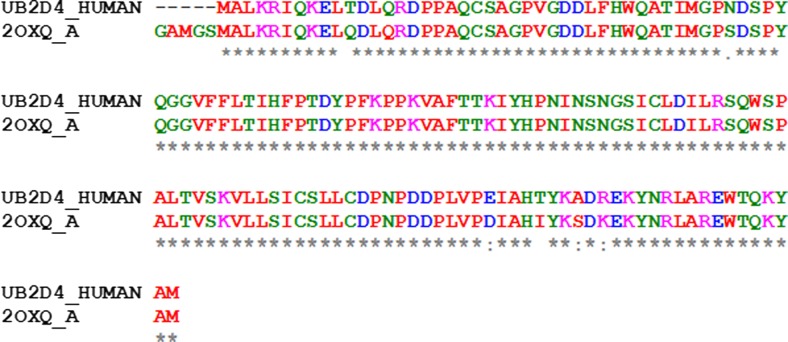

Homology modelling technique uses atomic coordinates of similar proteins which are experimentally determined, to predict the 3D model of a target protein [62]. The function of the protein can be inferred on the basis of its sequence similarity to a protein of known function [63]. The more similar the sequence is, the more similar the function of the proteins. Having 100% sequence identity yet preforming different roles according to their expression in different cellular and nuclear regions [64, 65] is biologically important for disease pathogenesis. The FASTA amino acid sequence of UBE2D4 was retrieved from the ExPASy/UniProt proteomics server (http://www.uniprot.org/). The UniProt accession code of the UBE2D4 enzyme is Q9Y2X8. The UBE2D4 protein consists of 147 amino acids and belongs to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme family. The template selection was carried out by submitting the FASTA sequence of the protein to BLASTp (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), JPred3 and Domain Fishing server tools. The template (PDB ID: 2OXQ) was selected based on sequence similarity, secondary structure similarity, domain similarity and statistical e-values (Table 1). Similar UBC conserved domain is expressed in all the members of ubiquitin conjugating enzyme family as observed in the BLAST server (Fig. 2). UBC domain of the E2s binds non-covalently to the ubiquitin and is implicated in the ubiquitin proteasome degradation process. The sequence alignment of the UBE2D4 with other E2s is carried out using CLUSTALW server to define the structurally conserved regions. The sequence similarity between the catalytic domain of UBE2D4 and the other E2s is shown in the supplementary fig S1. Pairwise sequence alignment of the UBE2D4 sequence with its template 2OXQ_A was carried out using CLUSTALW server as shown in Fig. 3. The aligned sequence was subjected to the 3D model generation. The sequence similarity of the UBE2D4 protein with its template is 95%.

Table 1.

Comparison of the template search results obtained from various servers for UBE2D4 protein

| S. no. | Name of the protein database server | Parameters (s) considered for template selection | e-value | PDB code of protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BLAST | Sequence position specificity | 1e−104 | 2OXQ_A |

| 2 | Jpred3 | Secondary structure prediction, solvent accessibility and coiled-coil region prediction | 5e−83 | 2OXQ_A |

| 3 | Domain Fishing | Domains in protein sequence | 4e−45 | 2OXQ_A |

The similarity and identity of the corresponding templates to the target protein as e-values were obtained from the BLAST, Jpred3 and Domain Fishing servers. The template 2OXQ_A was selected based on the e-value

Fig. 2.

Putative conserved domains and conserved motifs of the UBE2D4 protein. PLN00172 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme; provisional, UBCc ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, catalytic (UBCc) domain. Basic local alignment search tool illustrates that the UBE2D4 contains domains like, ubiquitin (Ub) thio-ester intermediate interaction domains, E3 interaction domains present in the UBc domain

Fig. 3.

Alignment of UBE2D4 protein with template sequences. Pair wise sequence alignment carried out with CLUSTALW server. The conserved residues are represented as asterisk and highly similar residues as colon, similar residues as period. Alignment of UBE2D4 with the template protein gives 95% sequence similarity

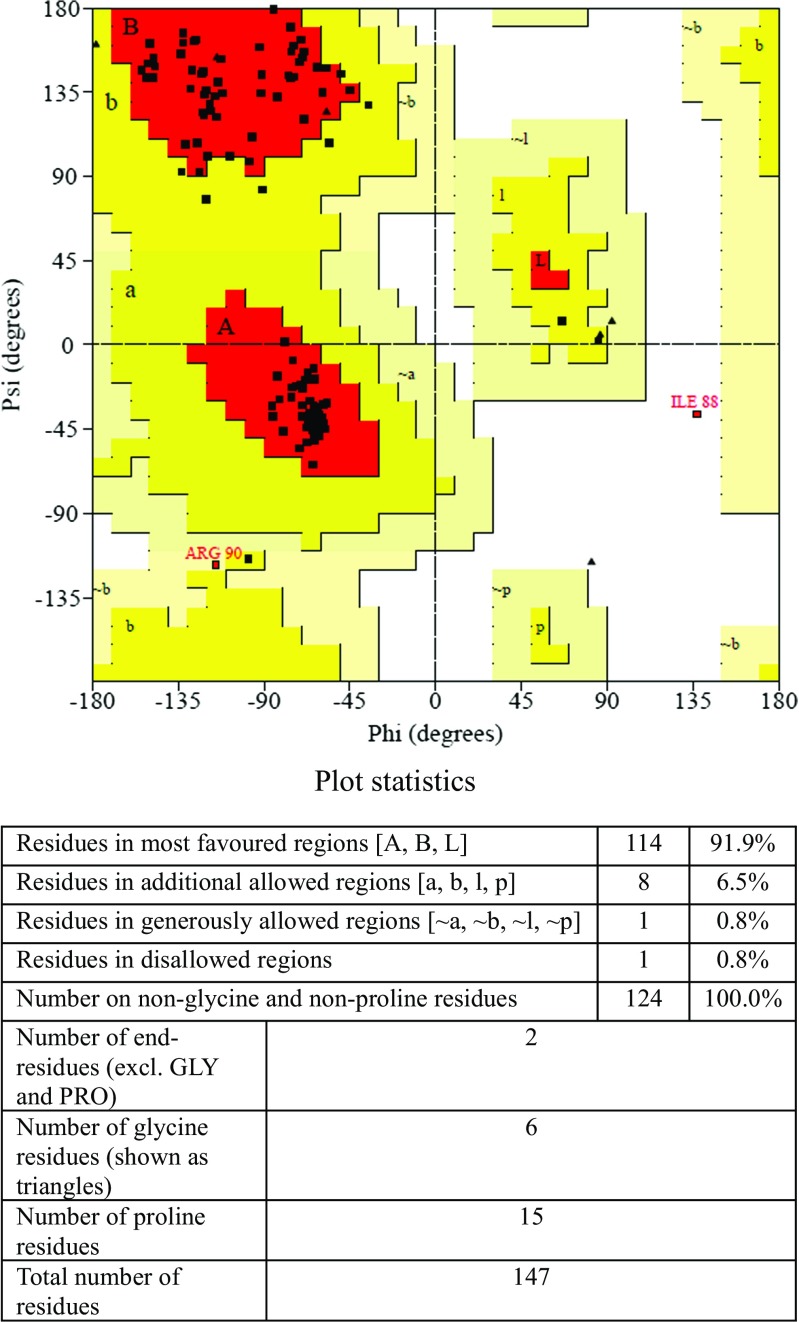

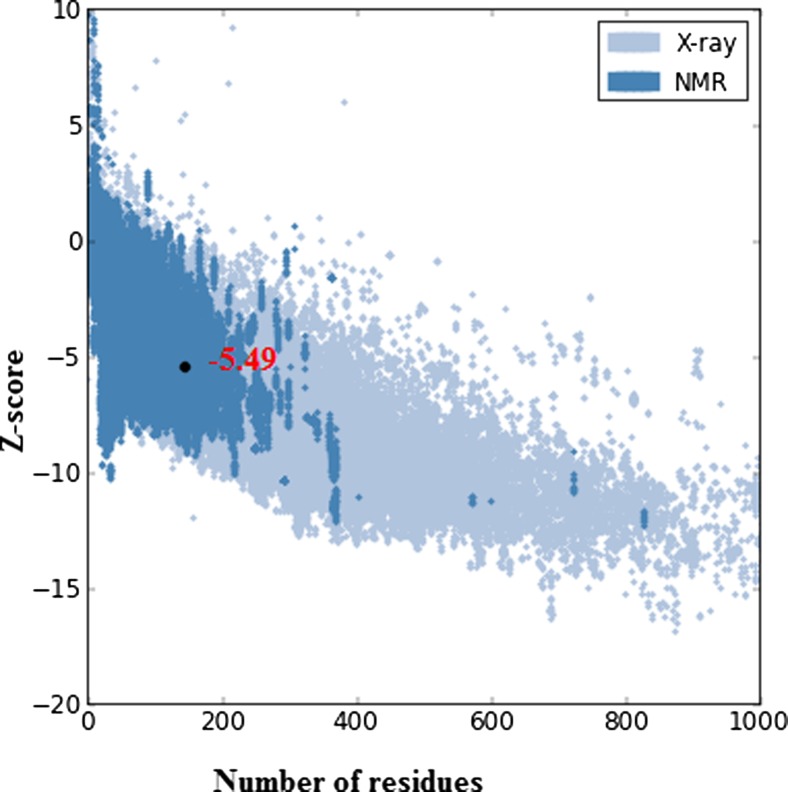

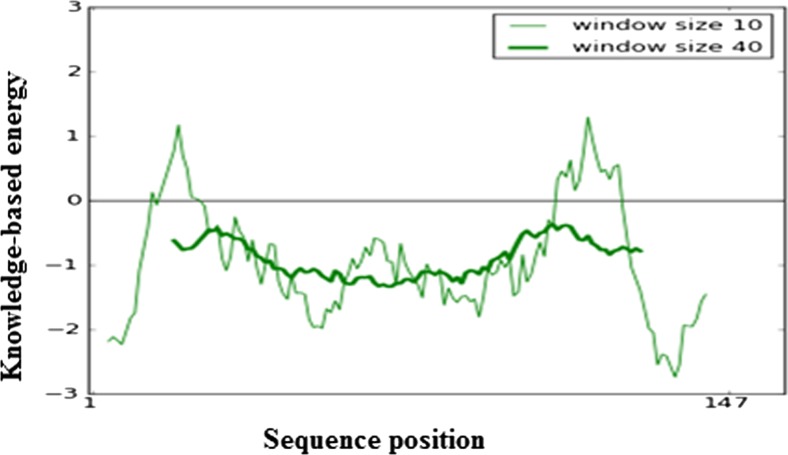

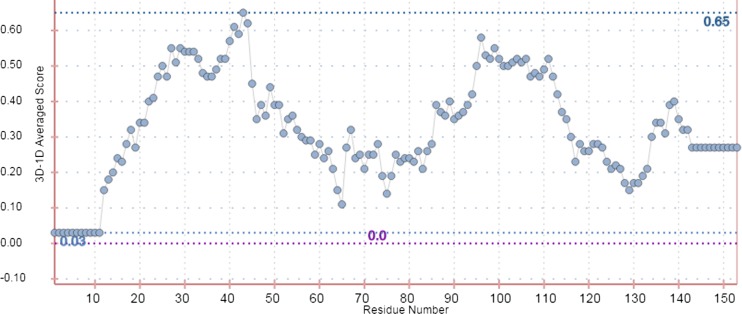

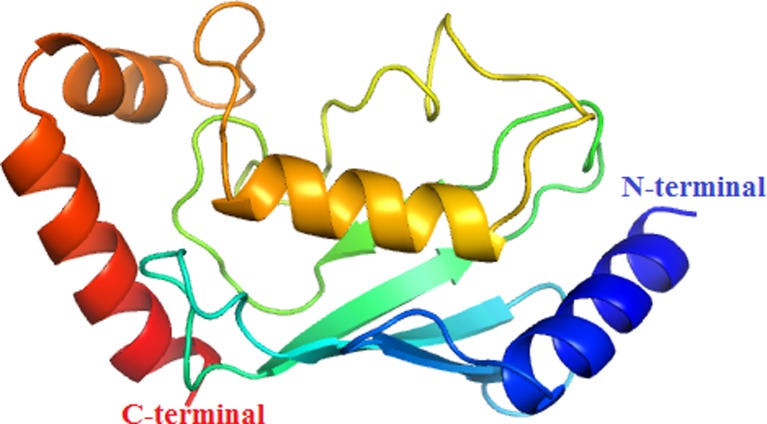

Thirty-two models were generated by the MODELLER 9.11 programme, and the model with the lowest MODELLER objective function was selected for validation studies. The UBE2D4 structure was energy minimized and optimized using protein preparation wizard in Schrödinger suite. The energies of the protein UBE2D4 calculated before and after energy minimization were 2.2 × 102 and −2.5 × 102 kcal/mol, respectively. Stereochemical quality of the energy minimized and refined 3D structure of the UBE2D4 was analysed by Ramachandran plot in PROCHECK server [35]. The Ramachandran contour plot provides the phi (Φ) versus psi (ψ) angles of amino acid residues which form the backbone of the protein and their stereochemical quality [36]. The plot statistics indicate that 91.9% of the residues are present in the most favoured regions, 6.5% of the residues in the additional allowed regions, 0.8% residues in the generously allowed regions and 0.8% of the residues in the disallowed region (Fig. 4). The model has ≥90% of the amino acid residues present in allowed regions represents a good quality model. Similar protocols were followed as reported recently in drug discovery process and lead identification [66–68]. The UBE2D4 model has 91.9% of the amino acid residues present in the allowed regions, and hence, it is a good quality model. The overall quality of the UBE2D4 protein was measured using ProSA server [37] (Fig. 5). ProSA server gives a z-score value of −5.49 for UBE2D4 model predicting the 3D model of the protein to be a good quality model. Amino acid residues with negative ProSA energies are reliable, and most of the amino acid residues of the UBE2D4 model are with negative energies as shown in Fig. 6. The VERIFY_3D server checks the stereochemistry of the model. VERIFY_3D server determines a scoring function to assess the quality of the UBE2D4 model. 85% residues of UBE2D4 protein have shown a score more than 0.2 that indicates the quality of the predicted model to be reliable (Fig. 7). The variation of the RMSD value of the validated UBE2D4 protein structure with its template PDB ID: 2OXQ is 0.14 Å, which is in the permissible range for a protein, i.e. ≤2 Å. The UBE2D4 model is validated by the superimposition of UBE2D4 model with other 26 crystal structures of E2s (5, 6). The RMSD values for the UBE2D4 to that other 26 E2 crystal structures are calculated in the Swiss-PDB Viewer (SPDBV_4.1.0) (Supplementary Table S1) [7], which are in the range of the acceptable RMSD value, i.e. ≤2 Å. Hence, the generated model is a good quality model. The validated 3D model of the protein UBE2D4 is shown in the Fig. 8. The secondary structure of UBE2D4 consists of four α helices and four β strands, and their corresponding amino acid residues are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Ramachandran plot of UBE2D4 protein. The red-coloured field in the plot indicates energetically the most favoured region. The yellow field represents the additionally allowed region, the light yellow represents the generously allowed and the white field indicates the disallowed region

Fig. 5.

ProSA z-score plot of the UBE2D4 protein. ProSA plot—the energy profile of UBE2D4 obtained using ProSA web server analysis showing z-score of −5.49. The ProSA–web z-scores of all protein chains in PDB determined by X-ray crystallography are shown in light blue and by NMR spectroscopy in dark blue

Fig. 6.

ProSA energy profile of UBE2D4 protein. The ProSA analysis of the model shows maximum residues in the negative energy region. The negative ProSA energies of UBE2D4 protein indicate a reliable arrangement of amino acids in the 3D structure

Fig. 7.

The VERIFY_3D profile of UBE2D4 protein. VERIFY_3D analyzes the compatibility of an atomic UBE2D4 model (3D) with its own amino acid sequence (1D). The scores of a sliding 21-residue window (from −10 to +10) are added and plotted for individual 147 residues. 85% of the residues have an average 3D–1D score >0.2

Fig. 8.

The 3D model of the UBE2D4 protein. The 3D structure of the UBE2D4 protein, which shows four alpha helices and four beta sheets

Table 2.

Details of the secondary structure of the UBE2D4 protein showing α-helices and β-strands

| S. no. | Start residue | End residue | No. of residues | Amino-acid sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) The α-helices in UBE2D4 protein | ||||

| 1 | Ala2 | Arg15 | 14 | ALKRIQKELTDLQR |

| 2 | Val99 | Cys111 | 13 | VSKVLLSICSLLC |

| 3 | Pro121 | Ala129 | 9 | PEIAHTYKA |

| 4 | Arg131 | Ala146 | 16 | REKYNRLAREWTQKYA |

| b) The β-strands in UBE2D4 protein | ||||

| 1 | Cys21 | Pro25 | 5 | CSAGP |

| 2 | His32 | Met38 | 7 | HWQATIM |

| 3 | Val49 | His55 | 7 | VFFLTHI |

| 4 | Lys66 | Phe69 | 4 | KVAF |

The UBE2D4 protein has 4α-helices and 4β-strands identified using PDBsum server

Active site prediction

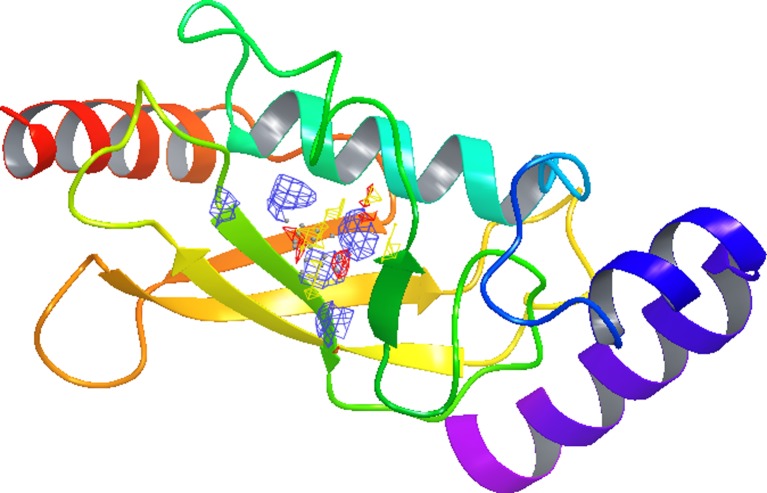

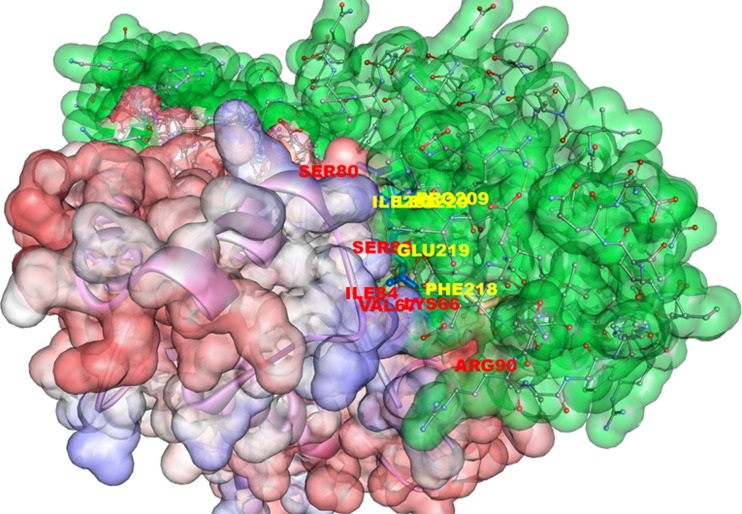

An enzyme or protein active site is defined as the region where it binds with its natural substrate and is involved in the catalytic reaction [69]. Identification of catalytic residues is an important step to know the function of enzymes [70]. The binding site regions and the active site residues were identified using CASTp, Q-site Finder and SiteMap tools; the results of which are shown in the Tables 3 and 4. The CASTp server tool [45] was used to identify the pockets and voids in the UBE2D4 protein structure. CASTp server provides the binding site of the UBE2D4 and its respective amino acid residues, with emphasis on mapping of surface pockets and interior voids. The UBE2D4 binding site residues are ILE 54, VAL 67, CYS 85, LEU 86, ASP 87, LEU 89, ARG 90, VAL 99, VAL 102, LEU 103 and ASP 117 identified from the CASTp server, and the residues present in the binding region are shown in Table 3. The Q-site Finder [46] was used to identify the ligand binding site in the UBE2D4 protein. The ligand binding site of UBE2D4 protein consists of the residues, PRO 64, PRO 65, LYS 66, VAL 67, ILE 84, CYS 85, LEU 86, ASP 87, LEU 89, ARG 90 and ASP 117. The Q-site Finder server uses the interaction energy between the UBE2D4 protein and a simple van der Waals probe to locate energetically favourable binding sites. The Q-site Finder server gives the probe binding sites in UBE2D4 protein with a single cluster that is within 1.6 Å. The SiteMap module identifies the hydrogen bond acceptor, hydrogen bond donor, hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions in the UBE2D4 protein (Fig. 9), and their volumes are as shown in the Table 4. The binding site region of UBE2D4 identified from the SiteMap consists amino acids, namely ALA 35–GLY 39, GLY 48–HIS 55, PRO 65–SER 91 and ILE 106. The protein-protein docking of the UBE2D4 and its natural substrate ubiquitin ligase CHIP was carried out using PatchDock server. PatchDock is a molecular docking tool used to identify the binding residues in the UBE2D4 protein. The active site residues, LYS 66, VAL 67, SER 80, SER 83, ILE 84 and ARG 90 of UBE2D4 protein were observed to participate in the formation of docked complex with the ubiquitin ligase CHIP (Fig. 10). All the active site residues are present in the ubiquitin binding domain (Fig. 2). Similar protocols were also reported earlier for the identification of the active site in the proteins [71–74].

Table 3.

UBE2D4 protein binding cavities identified using the CASTp and Q-site Finder servers

| S. no. | CASTp | Q-site Finder | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (Å3) | Residues | Volume (Å3) | Residues | |

| 1 | 51.50 | CYS 85, LEU 86, ASP 87, LEU 89, ARG 90, ASP 117 |

87 | ILE 84, CYS 85, LEU 86, ASP 87, LEU 89, ARG 90, ASP 117 |

| 2 | 15.60 | ILE 54, VAL 67, VAL 99, VAL 102, LEU 103 |

121 | PRO 64, PRO 65, LYS 66, VAL 67, SER 83, ILE 84, LEU 89, ARG 90 |

The binding cavities were identified using CASTp and Q-site Finder servers based on the hydrophobicity and the ligand binding site prediction, respectively

Table 4.

Putative active site region in UBE2D4 protein predicted using SiteMap

| Nature of binding | Area (Å2) |

|---|---|

| Hb acceptor | 113.34 |

| Hb donor | 150.5 |

| Hydrophilic | 284.45 |

| Hydrophobic | 30.4 |

| Surface | 504.9 |

The SiteMap module of the Schrödinger suite was used to identify the binding sites of the protein

Fig. 9.

The binding site region in UBE2D4 protein predicted using SiteMap. The UBE2D4 protein is represented in solid ribbon form. The active site shown in mesh fashion represents hydrogen bond acceptors in red, hydrogen bond donors in blue and hydrophobic region in yellow

Fig. 10.

Protein-protein docking of UBE2D4 and its natural substrate ubiquitin ligase CHIP. The protein-protein docking (molecular surface figure) of the UBE2D4 with its natural substrate ubiquitin ligase CHIP was carried out using PATCH DOCK server. The UBE2D4 protein active site residues LYS 66, VAL 67, SER 80, SER 83, ILE 84 and ARG 90 bind with the ubiquitin ligase CHIP

Virtual screening studies

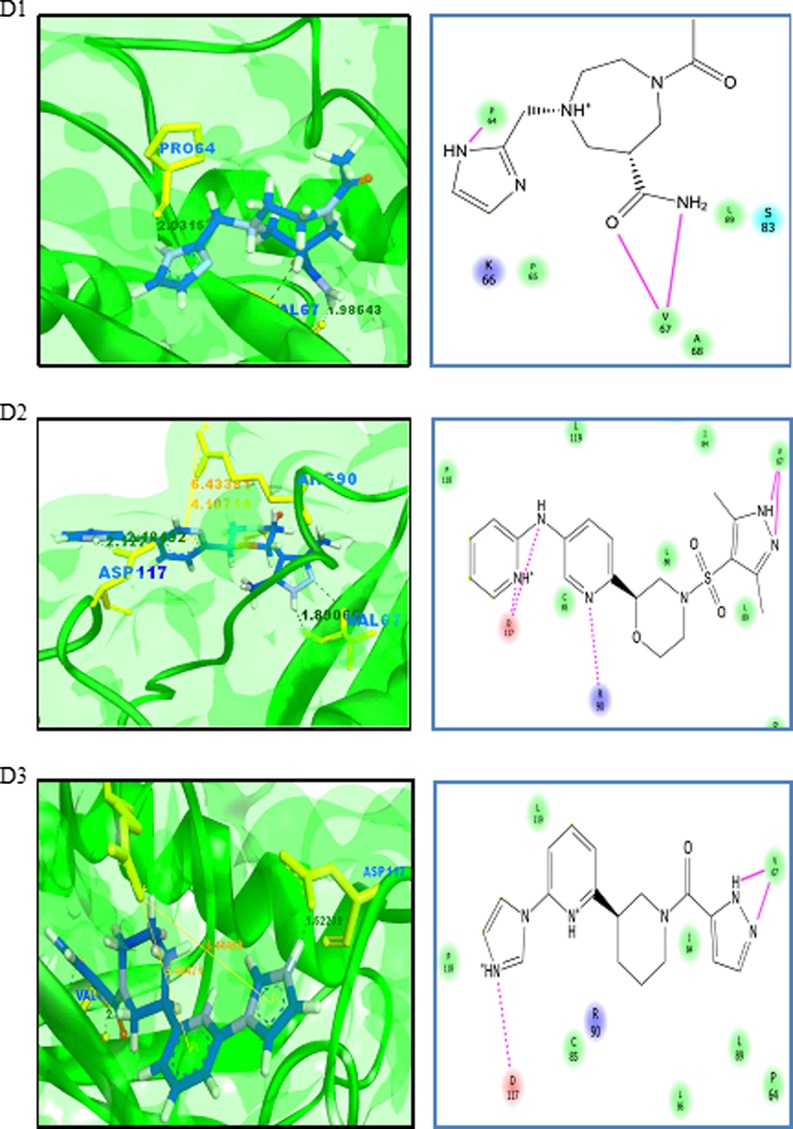

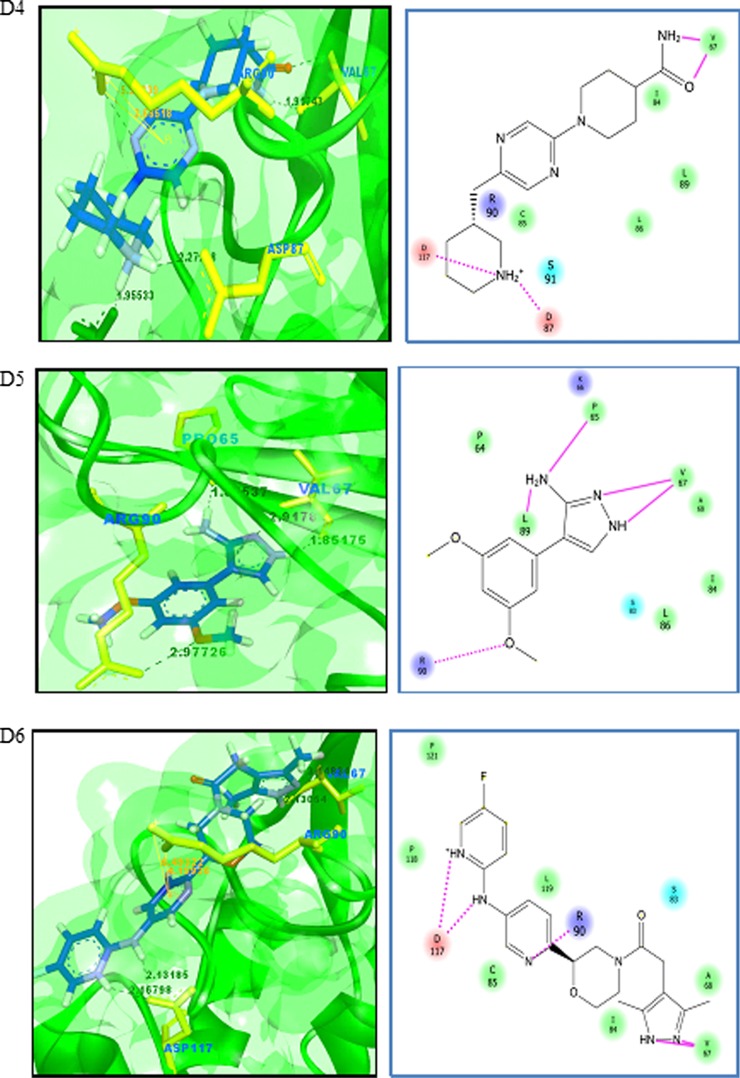

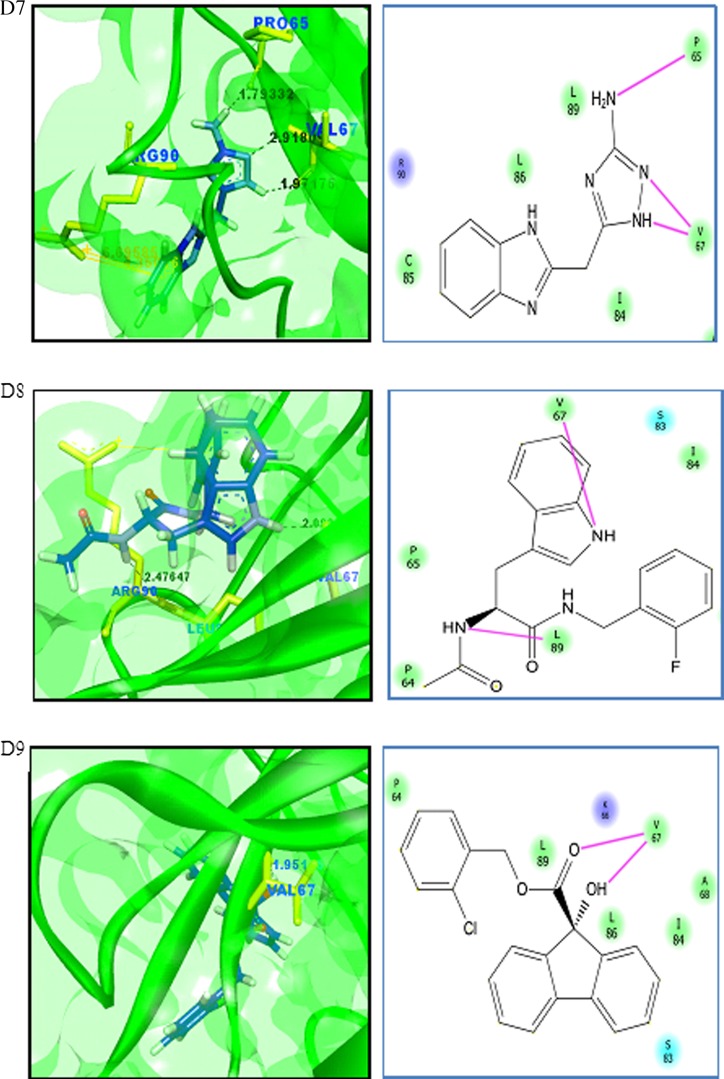

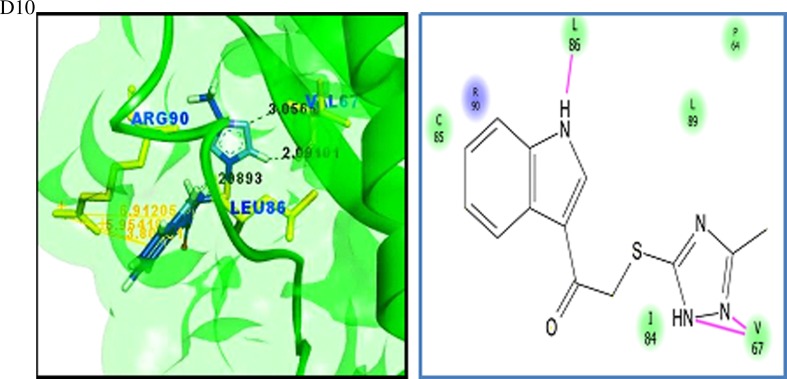

Virtual screening is a computational method used to identify novel chemical structures that selectively bind to the target protein using standard protocols [75, 76]. A grid was generated at the active site region using the Glide module of the Schrödinger suite. Active site grid with 80 Å × 80 Å × 80 Å dimensions was considered for the site-directed virtual screening studies. The LigPrep module for ligand preparation was used for the preparation of the ligand database. The CB_Div set database contains 20,000 molecules, and the ligand structures obtained after the ligand preparation are 33,927. The Asinex BioDesign structural database contains the 48,291 molecular structures, and the ligands obtained after ligand preparation are 218,722 molecules. The prepared ligand structures and the protein active site grid were subjected to the virtual screening workflow. The ligands were docked flexibly through HTVS/SP/XP modes of the Glide module in Schrödinger suite that uses OPLS_2005 force filed. In each stage, 10% of the molecules were filtered, and finally, XP docked complexes were obtained. The HTVS mode filtered the subjected ligands from CB_Div Set and Asinex BioDesign and 4209 and 26,182 ligands were obtained as output, respectively. Resultant docked ligand complexes from XP mode were 42 and 261 ligands from the databases CB_Div Set and Asinex BioDesign. A total of 303 docked complexes were obtained from the virtual screening. A sample of ten docked complexes is shown in Fig. 11 (D1 to D10). The protein-ligand complexes were prioritized based on the glide score and glide energy (Table 5). The ligand molecules show a glide score ranging from −8.80 to −6.54. The docked complexes show hydrogen bond interaction and pi-cation interaction, and their bond lengths were analysed using Accelrys Discovery Visualizer and shown in Table 5.

Fig. 11.

Binding interactions of UBE2D4 protein with the ligand molecules. The protein is represented in green solid ribbon form and the ligand in blue stick form. The hydrogen bond interactions are represented in black and Pi–cation interactions in orange. UBE2D4 protein amino acid residues are represented in green yellow sticks. The interactions in the protein-ligand complex are explained by the 2D diagram (D1 to D10). The non-ionic interactions of the ligand molecules with protein amino acid residues are shown in pink lines

Table 5.

The structures of ligands and the intermolecular interactions between the ligand molecules and UBE2D4 protein in the docked complexes

The top 10 ligand molecules obtained in the virtual screening were screened in the extra precession (XP) mode of the Glide module in Schrodinger suite, against the other E2 enzymes, namely UBE2D2, UBE2D3, UBE2V2 and UBE2N. The docking study shows the interactions in the UBC domains of the E2s, similar to that of UBE2D4 (Supplementary Table S2). The ligands D1 to D10 do not show specific and selective binding in the catalytic domain of other 4 E2 enzymes (UBE2D2, UBE2D3, UBE2V2 and UBE2N). The ligands D1 to D10 do not show specific and selective binding in the catalytic domain of other four E2 enzymes mentioned here. Hence, the ligands bind specifically towards the UBE2D4, which is unique.

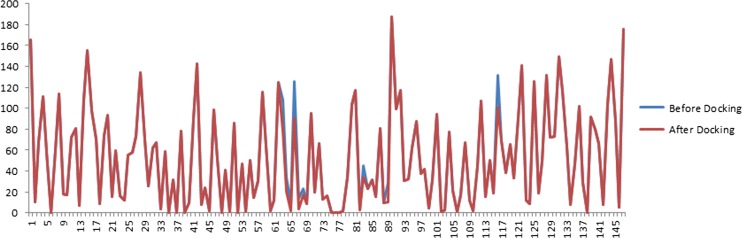

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) and pharmacophore analysis

The SASA values of the ligand and protein structure were calculated and analysed using Accelrys Discovery Visualizer 3.5. The SASA values before and after docking are shown in Fig. 12. The active site residues that have shown decreased SASA values are PRO 64, VAL 67, ASP 84, ARG 90 and ASP 117. The amino acids with hydrophobic nature like proline, valine, charged aspartic acid and arginine form an active site region with an 80 Å3 volume in UBE2A protein. The identified UBE2A protein active site residues are PRO 64, VAL 67, ASP 84, ARG 90 and ASP 117 that are involved in the ubiquitin ligase docking study.

Fig. 12.

SASA graph of the UBE2D4 protein before and after docking. The decreased SASA values of the UBE2D4 protein active site is shown in the graph. The residues PRO 64, VAL 67, ASP 84, ARG 90 and ASP 117 show less surface accessibility after docking. The maroon line after docking and the blue line represents before docking

The docked ligand molecules show a similar binding pattern with heterocyclic nitrogen containing ring structures, actively involved in binding with the protein (Table 5 and Fig. 11). The majority of the ligand molecules consist of the pyridine, piperidine and azol moieties as pharmacophoric groups in their structures (Table 5). The ligand molecules D1, D3, D6, D7 and D10 contain the azol rings as a common structural scaffold. The ligand molecules D2 and D6 consist of the pyridine ring structure, and other ligand molecules such as D4, D5, D8 and D9 contain similar heterocyclic ring structures. The pyridine, piperidine and azol scaffolds are shown in our study to act as selective pharmacophores for binding with UBE2D4 protein. The heterocyclic nitrogen compounds are reported earlier to play a vital role in cancer drug discovery process [77].

Pharmacokinetic properties analysis

QikProp is used to evaluate the pharmacologically desirable properties of the ligand molecules with new scaffolds and their analogues as compared to that for known drugs [60]. The ADME properties of the ligands were predicted to evaluate the molecules for the druggability (59). All the ligand molecules show ADME properties within the acceptable range as shown in Table 6. These ligand molecules adhere to the Lipinski’s rule of five [78] and Jorgenson’s rule of three [79]. The ligand structures exhibit the properties in the acceptable range of Lipinski’s rule of five (molecular weight <500, QPlogPo/w <5, hydrogen bond donor ≤5 and hydrogen bond acceptor ≤10) [60]. These ligand molecules may be considered for design of cancer drugs.

Table 6.

ADME or pharmacokinetic predictions of the docked molecules of CB_Div Set and Asinex BioDesign virtual library using QikProp

| S. no. | CNS | Mol. wt | Donor HB | Accept HB | QPlog Po/w | Qplog BB | % Human oral absorption | Rule of three | Rule of five |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | −1 | 256.31 | 3.00 | 9.00 | −1.83 | −0.83 | 35.35 | 1 | 0 |

| D2 | −2 | 444.48 | 1.00 | 8.70 | 2.40 | −1.25 | 85.03 | 1 | 0 |

| D3 | −1 | 322.36 | 1.00 | 6.50 | 2.47 | −0.87 | 88.73 | 0 | 0 |

| D4 | 0 | 303.40 | 3.00 | 6.50 | 0.67 | −0.66 | 60.57 | 0 | 0 |

| D5 | −1 | 219.24 | 3.00 | 3.50 | 1.33 | −0.61 | 86.25 | 0 | 0 |

| D6 | −1 | 410.45 | 2.00 | 8.20 | 2.35 | −0.91 | 85.04 | 1 | 0 |

| D7 | −2 | 214.22 | 4.00 | 4.50 | 0.37 | −1.23 | 69.46 | 0 | 0 |

| D8 | −1 | 353.39 | 2.25 | 4.25 | 3.00 | −0.66 | 90.65 | 0 | 0 |

| D9 | 0 | 350.80 | 1.00 | 2.75 | 4.86 | −0.34 | 100.00 | 0 | 0 |

| D10 | −1 | 272.32 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 2.60 | −0.83 | 90.14 | 0 | 0 |

The ADME permissible ranges are as follows: CNS −2(inactive) +2(active), Mol wt (130–725), Donor HB (0.0–6.0), Accept HB (2.0–20.0), QPlog Po/w (−2.0 to 6.5), QPlog BB (−3.0 to −1.2), %Human oral absorption >80% high, <25% low, Rule of three (3), Rule of five (4)

Conclusion

The 3D structure of the UBE2D4 is generated and evaluated using homology modelling methods. The evaluated 3D model is validated stereochemically using standard computational protocols. The active site of the protein was identified, and the residues that are involved in the binding with the substrates are predicted. The active site residues of UBE2D4, namely PRO 65, LYS 66, VAL 67, ASP 84, ARG 90 and ASP 117, are important for binding with its natural substrate. The ligand molecules obtained from virtual screening contain pyridine, piperidine and azol ring scaffolds, which may act as the pharmacophore. The interactions of these ligand structures in the predicted active site of the protein UBE2D4 show consistency in binding pattern between the binding residues and the amine and carbonyl functional group of the ligands. The ligand structures exhibit acceptable range of predicted ADME properties. Several ligand scaffold structures are reported in our study, which may be considered as drug candidates for later stage of cancer drug discovery.

Electronic supplementary material

Alignment of the UBE2D4 sequence with the other E2 sequences. The alignment file was generated using CLUSTALW server tool. The UBC domain of UBE2D4 is conserved in all the E2s. The UBE2D4 conserved domain sequence starts from LYS 4 and ends with THR 142 amino acid residue. (GIF 7718 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 100 kb)

Acknowledgements

The author VR acknowledges the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India, for the financial support (File No: 09/132(0821)/2012-EMR-I). The authors VR, RKD, RV, SPV and RR acknowledge the Principal and Head, Department of Chemistry, University College of Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad, for providing facilities to carry out this work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical standards

The authors state that no human studies and no animal studies were carried out for this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Pittet JM. The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:447–462. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng M, Chen Y, Xiao W, Sun R, Tian Z. NK cell-based immunotherapy for malignant diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:230–252. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciechnover A. The unravelling of the ubiquitin system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:322–324. doi: 10.1038/nrm3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nalepa G, Rofle M, Harper WJ. Drug discovery in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:596–613. doi: 10.1038/nrd2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarita Rajender P, Ramasree D, Bhargavi K, Vasavi M, Uma V. Selective inhibition of proteins regulating CDK/cyclin complexes: strategy against cancer—a review. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2010;30:206–213. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2010.488649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciechanover A. Proteolysis: from the lysosome to ubiquitin and the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:79–87. doi: 10.1038/nrm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muratani M, Tansey PT. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrm1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedford L, Lowe J, Dick LR, Mayer RJ, Brownell JE. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation and the ubiquitin-proteasome system as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:29–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu R, Hochstrasser M. Recent progress in ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like protein (Ubl) signalling. Cell Res. 2016;26:389–390. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mani A, Gelmann EP. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and its role in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4776–4789. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye Y, Rape M. Building ubiquitin: E2 enzymes at work. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:755–764. doi: 10.1038/nrm2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berndsen CE, Wolberger C. New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:301–307. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Severe N, Dieudonne FX, Marie PJ. E3 ubiquitin ligase-mediated regulation of bone formation and tumorigenesis. Cell Death Disease. 2013;4:1–10. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Z, Kohli E, Devlin IK, Bold M, Nix CJ, Misra S. Interactions between the quality control ubiquitin ligase CHIP and ubiquitin conjugating enzymes. BMC Struct Biol. 2008;8:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang J, Ballinger CA, Wu Y, Dai Q, Cyr DM, Hohfeld J, Patterson C. CHIP is a U-box-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase identification of Hsc70 as a target for ubiquitinylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42938–42944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kajiro M, Hirota R, Nakajima Y, Kawanowa K, So-ma K, Ito I, Yamaguchi Y, Ohie S, Kobayashi Y, Seino Y, Kawano M, Kawabe Y, Takei H, Hayashi S, Kurosumi M, Murayama A, Kimura K, Yanagisawa J. The ubiquitin ligase CHIP acts as an upstream regulator of oncogenic pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:312–319. doi: 10.1038/ncb1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavasotto NC, Phatak SS. Homology modeling in drug discovery: current trends and applications. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillisch A, Pineda FL, Hilgenfeld R. Utility of homology models in the drug discovery process. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:659–669. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alpi E, Griss J, da Silva AW, Bely B, Antunes R, Zellner H, Rios D, O’Donovan C, Vizcaino JA, Martin MJ. Analysis of the tryptic search space in UniProt databases. Proteomics. 2015;15:48–57. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:20–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye J, McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: improvements for better sequences analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christian C, Jonathan DB, Geoffrey JB. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:197–201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Contreras-Moreira B, Bates PA. Domain fishing: a first step in protein comparative modeling. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1141–1142. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.8.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonnet GH, Cohen MA, Benner SA. Exhaustive matching of the entire protein sequence database. Science. 1992;256:1443–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1604319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2014;47:5.6.1–5.6.32. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0506s47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson M, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling and its applications to drug discovery. Annu Rep Med Chem. 2004;39:259–276. doi: 10.1016/S0065-7743(04)39020-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banks JL, Beard HS, Cao Y, Cho AE, Damm W, Farid R, Felts AK, Halgren TA, Mainz DT, Maple JR, Murphy R, Philipp DM, Repasky MP, Zhang LY, Berne BJ, Friesner RA, Gallicchio E, Levy RM (2005) Integrated modeling program, applied chemical theory (IMPACT). J Comput Chem 26:1752–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Shivakumar D, Williams J, Wu Y, Damm W, Shelley J, Sherman W. Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the OPLS force field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:1509–1519. doi: 10.1021/ct900587b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorgensen WL, Tirado-Rives J. The OPLS (optimized potentials for liquid simulations) potential functions for proteins, energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;110:1657–1666. doi: 10.1021/ja00214a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHEK: a program to check the stereo chemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou AQ, O’Hern CS, Regan L. Revisiting the Ramachandran plot from a new angle. Prot Sci. 2011;20:1166–1171. doi: 10.1002/pro.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:407–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sippl MJ. Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:355–362. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalman M, Ben-Tal N. Quality assessment of protein model-structures using evolutionary conservation. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1299–1307. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. Assessment of protein models with three dimensional profiles. Nature. 1992;356:83–85. doi: 10.1038/356083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris AL, MacArthur MW, Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins. 1992;12:345–364. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang F, Han W, YD W. Influence of side chain conformations on local conformational features of amino acids implication for force field development. J Phys Chem. 2010;114:5840–5850. doi: 10.1021/jp909088e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sippl MJ. Knowledge-based potentials for proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0959-440X(95)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bowie JU, Luthy R, Eisenberg D. A method to identify protein sequences that fold into a known three-dimensional structure. Science. 1991;253:164–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1853201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:162–173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Seng TJ, Binkowski A, Trupaz Y, Liang J. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:116–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laurie AT, Jackson RM. Q-site finder: an energy-based method for the prediction of protein-ligand sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1908–1916. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halgren T. Identifying and characterizing binding sites and assessing druggability. J Chem Inf Mod. 2009;49:377–389. doi: 10.1021/ci800324m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:363–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binkowski TA, Naghibzadeh S, Liang J. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3352–3355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang J, Edelsbrunner H, Woodward C. Anatomy of protein pockets and cavities: measurement of binding site geometry and implications for ligand design. Prot Sci. 1998;7:1884–1897. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halgren TA. New method for fast and accurate binding site identification and analysis. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;69:146–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reddy AS, Priyadarshini PS, Kumar PP, Pradeep HN, Sastry GN. Virtual screening in drug discovery—a computational perspective. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2007;8:329–351. doi: 10.2174/138920307781369427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitchen DB, Decornez H, Furr JR, Bajorath J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:935–949. doi: 10.1038/nrd1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Girke T, Cheng LC, Raikhel N. ChemMine. A compound mining database for chemical genomics. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:573–577. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen IJ, Folopee N. Drug-like bioactive structures and conformational coverage with the LigPrep/ConfGen suite: comparison to programs MOE and catalyst. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50:822–839. doi: 10.1021/ci100026x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elokely MK, Doerksen JR. Docking challenge: protein sampling and molecular docking performance. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:1934–1945. doi: 10.1021/ci400040d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic encloser for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durham E, Dorr B, Woetzel N, Staritzbichler R, Meiler J. Solvent accessible surface area approximations for rapid and accurate protein structure prediction. J Mol Model. 2009;15:1093–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00894-009-0454-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lill MA, Danielson ML. Computer-aided drug design platform using PyMOL. J Comput Aid Mol Des. 2011;25:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ioakimids L, Thoukydidis L, Mirza A, Naeem S, Reynisson J. Benchmarketing the reliability of QikProp. Correlation between experimental and predicted values. QSAR Comb Sci. 2008;27:445–456. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200730051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwede T. Protein modelling: what happened to the “protein structure gap”. Structure. 2013;21:1531–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee D, Redfern O, Orengo C. Predicting protein function from sequence and structure. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:995–1005. doi: 10.1038/nrm2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whisstock JC, Lesk AM. Prediction of protein function from protein sequence and structure. Q Rev Biophys. 2003;36:307–340. doi: 10.1017/S0033583503003901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watson JD, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Predicting protein function from sequence and structural data. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dumpati R, Dulapalli R, Kondagari B, Ramatenki V, Vellanki S, Vadija R, Vuruputuri U. Suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 as a drug target for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a structure-guided approach. Chemistry Select. 2016;1:2502–2514. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sasikala D, Jeyakanthan J, Srinivasan R. Structural insights on identification of potential lead compounds targeting WbpP in vibrio vulnificus through structure-based approaches. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2016;36:515–530. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2015.1132237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vadija R, Mustyala KK, Niambigari N, Dulapalli R, Dumpati RK, Ramatenki V, Vellanki SP, Vuruputuri U. Homology modeling and virtual screening studies of FGF-7 protein—a structure-based approach to design new molecules against tumor angiogenesis. J Chem Biol. 2016;9:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s12154-016-0152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yahalom R, Reshef D, Wiener A, Frankel S, Kalisman N, Lerner B, Keasar C. Structure-based identification of catalytic residues. Proteins. 2011;79:1952–1963. doi: 10.1002/prot.23020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartlett GJ, Porter CT, Borkakoti N, Thornton JM. Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:105–121. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mustyala KK, Malkhed V, Chittireddy VRR, Vuruputuri U. Identification of small molecular inhibitors for efflux protein: DrrA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2016;9:190–202. doi: 10.1007/s12195-015-0427-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh T, Biswas D, Jayaram B. AADS—an automated active site identification, docking and scoring protocol for protein targets based on physicochemical descriptors. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:2515–2527. doi: 10.1021/ci200193z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramatenki V, Potlapally SR, Dumpati RK, Vadija R, Vuruputuri U. Homology modeling and virtual screening of ubiquitin conjugation enzyme E2A for designing a novel selective antagonist against cancer. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2015;35:536–549. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2014.969375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Malkhed V, Mustyala KK, Potlapally SR, Vuruputuri U. Identification of novel leads applying in silico studies for mycobacterium multidrug resistant (MMR) protein. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2014;32:1889–1906. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2013.842185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sliwoski G, Kothiwale S, Meiler J, Lowe EW., Jr Computational methods in drug discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;66:334–395. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lionta E, Spyrou G, Vassilatis DK, Cournia Z. Structure-based virtual screening for drug discovery: principles, applications and recent advances. Curr Top Med Chem. 2014;14:1923–1938. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140929124445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martins P, Jesus J, Santos S, Raposo LR, Roma-Rodrigues C, Baptista PV, Fernandes AR. Heterocyclic anticancer compounds: recent advances and the paradigm shift towards the use of nanomedicine’s tool box. Molecules. 2015;20:16852–16891. doi: 10.3390/molecules200916852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lipinski AC. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Congreve M, Carr R, Murray C, Jhoti H. A ‘rule of three’ for fragment-based lead discovery? Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:876–877. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Alignment of the UBE2D4 sequence with the other E2 sequences. The alignment file was generated using CLUSTALW server tool. The UBC domain of UBE2D4 is conserved in all the E2s. The UBE2D4 conserved domain sequence starts from LYS 4 and ends with THR 142 amino acid residue. (GIF 7718 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 100 kb)