Abstract

AIM

To assess the occurrence of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) in pancreatic resections performed for focal pancreatic enlargement.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of medical records of all patients who underwent pancreatic resection for a focal pancreatic enlargement at our tertiary center from January 2000 to July 2013. The indication for surgery was suspicion of a tumor based on clinical presentation, imaging findings and laboratory evaluations. The diagnosis of AIP was based on histology findings. An experienced pathologist specialized in pancreatic disease reviewed all the cases and confirmed the diagnosis in pancreatic resection specimens suggestive of AIP. The histological diagnosis of AIP was set according to the international consensus diagnostic criteria.

RESULTS

Two hundred ninety-five pancreatic resections were performed in 201 men and 94 women. AIP was diagnosed in 15 patients (5.1%, 12 men and 3 women) based on histology of the resected specimen. Six of them had AIP type 1, nine were diagnosed with AIP type 2. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PC) was also present in six patients with AIP (40%), all six were men. Patients with AIP + PC were significantly older (60.5 vs 49 years of age, P = 0.045), more likely to have been recently diagnosed with diabetes (67% vs 11%, P = 0.09), and had experienced greater weight loss (15.5 kg vs 8.5 kg, P = 0.03) than AIP patients without PC. AIP was not diagnosed in any patients prior to surgery; however, the diagnostic algorithm was not fully completed in every case.

CONCLUSION

The possible co-occurrence of PC and AIP suggests that preoperative diagnosis of AIP does not rule out simultaneous presence of PC.

Keywords: Chronic pancreatitis, Pancreatic cancer, IgG4-related disease, Autoimmune pancreatitis, Malignancy

Core tip: In this retrospective study we confirmed that a considerable proportion of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for tumor suspicion have autoimmune pancreatitis. Furthermore, we show here the largest ever published group of patients with pancreatic cancer and autoimmune pancreatitis co-occurrence. The possible synchronous occurrence of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer implies major clinical consequences as the preoperative diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis might not rule out pancreatic cancer. Patients with autoimmune pancreatitis and patients with autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer differed in age at presentation, presence of diabetes and the extent of weight loss.

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a rare clinical entity with an estimated prevalence of 0.82-2.2/100000 inhabitants in Japan[1,2]. The prevalence of this disease in Western countries remains to be determined. AIP is diagnosed in only about 6% of patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis[3]. Within this group, AIP is defined by specific clinical, laboratory, radiological, and histological findings[4]. Currently, two subtypes of AIP are recognized. Type 1, also known as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, is considered a pancreatic manifestation of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. Type 2, idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis, is often associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Type 1 disease is characterized by sclerosing storiform fibrosis with a lymphoplasmatic infiltrate rich in IgG4-positive plasma cells, and elevated serum IgG4 levels[5]. Type 2 disease is characterized by disruption of the duct wall due to invasion by neutrophilic granulocytes, i.e., granulocytic epithelial lesions, absence of IgG4-positive plasma cells, and no serum elevation of IgG4. These characteristic changes may result in diffuse swelling or focal enlargement of the organ. Patients with AIP often present with jaundice, abdominal pain and focal pancreatic enlargement. The lack of specific symptoms makes the diagnosis of AIP difficult.

Diagnostic algorithms from Japan, South Korea and United States were proposed in 2006[6-8]. The international consensus diagnostic criteria (ICDC) published in 2011, unify the previous diagnostic strategies while respecting regional differences in clinical practice[4]. The ICDC are based on evaluation of the pancreatic parenchyma by imaging (CT, MRI), the structure of the pancreatic duct, histology, serology, involvement of other organs, and response to corticosteroid therapy. A typical, although not the most common, imaging finding is diffuse enlargement of the pancreas. This may be accompanied by delayed enhancement (sausage-like pancreas or rim-like enhancement); however, often only segmental or focal enlargement of the pancreas is seen, especially in AIP type 2[9,10]. Consequently, differentiating pancreatic cancer (PC) from AIP can be difficult and requires demonstration of a combination of clinical, serological, morphological and histological features. Despite the availability of well-defined diagnostic criteria, 6%-8% of patients with a pancreatic mass undergo unnecessary resection prior to a finding of autoimmune pancreatitis[11].

The aim of our study was to determine the proportion of patients at our center with AIP among those who had a pancreatic resection for a pancreatic mass and to define the clinical characteristics of this subgroup.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed medical records of all patients who underwent pancreatic resection for a focal pancreatic enlargement at the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine from January 2000 to July 2013. The indication for surgery was suspicion of a tumor based on clinical presentation, imaging findings and laboratory evaluations. Many patients were referred to our tertiary center for pancreatic surgery with a diagnostic workout already done in the referring hospital and with an established diagnosis of suspected pancreatic cancer.

The diagnosis of AIP was based on histology findings. An experienced pathologist (J.M.) specialized in pancreatic diseases (hundreds of PC and chronic pancreatitis cases reported) reviewed all the cases and confirmed the diagnosis in pancreatic resection specimens suggestive of AIP. The histological diagnosis of AIP was based on the ICDC criteria. In AIP type 1, the presence of storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and abundant IgG4-positive plasma cells was required, granulocytic epithelial lesions were indicative of AIP type 2[4].

The Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis of quantitative data and the Fisher’s exact test was used for qualitative data. A P-value of 0.05 was required for statistical significance. Data were analyzed by the center statistician using JMP 10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

The study was performed according to Declaration of Helsinki including the changes accepted in Soul, South Korea, during the 59th WMA General Assembly.

RESULTS

During the study period, we performed a total of 295 pancreatic resections in 201 men (68%) and 94 women (32%) with a median age of 61 (36-78) years. Pathological examination of the resected specimens revealed AIP in 15 patients (5.1%); 12 men and 3 women with a median age of 57 (35-67) years. A diagnosis of AIP was considered, but not confirmed, in two of these patients prior to pancreatectomy. In 13 of those patients (87%), the indication for resection was preoperative focal enlargement in the pancreatic head; two patients had an expansion of the tail. Six patients (40%), all men with a median age of 53 (46-67) years, were diagnosed with AIP type 1. Nine patients (60%), six men and three women with a median age of 58 (35-64) years had pathological findings consistent with AIP type 2.

In six patients (40%) with AIP (two AIP type 1 and four AIP type 2), a PC was also present in the resected tissue (Figure 1A-D). In five patients the cancer was localized in the head of the pancreas and in one patient the pancreatic tail was affected. The characteristics of AIP patients with and without PC are shown in Table 1. All patients with AIP and PC were men, and their median age was 60.5 (54-67) years. All patients with AIP + PC had a history of significant weight loss (median 15.5kg, range 8-50), which was greater than the weight loss present in the six AIP patients without PC (median 8.5kg, range 3-12, P = 0.03). Patients with AIP + PC were significantly older (median age 60.5 vs 49, P =0.045) and were more likely to have been diagnosed with recent-onset diabetes mellitus (within six months prior to resection) in the preoperative period (67% vs 11%, P = 0.09). History of smoking was similar in both groups (56% AIP patients vs 67% AIP + PC patients). There was not a statistically significant difference in the presence of jaundice between the groups. Histopathological findings in patients with AIP + PC are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Histological findings in resected pancreatic tissue in a patient with synchronous presence of type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. A: Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP), hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, original magnification × 40; B: AIP showing storiform fibrosis, HE staining, original magnification × 40; C: AIP with immunohistochemical staining of plasma cells for IgG4; D: Pancreatic cancer, HE staining, original magnification × 40.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis + pancreatic cancer n (%)

| AIP without PC | AIP with PC | P value | |

| Total | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | |

| AIP type 1 | 4 (44) | 2 (33) | |

| AIP type 2 | 5 (56) | 4 (67) | |

| Sex (males) | 6 (67) | 6 (100) | |

| Age | 49 (35-64) | 60.5 (54-67) | 0.045 |

| Smoking | 5 (56) | 4 (67) | |

| Recent onset of diabetes mellitus | 1 (11) | 4 (67) | 0.090 |

| History of another autoimmune disorder | 4 (44)1 | 0 | |

| History of pancreatic disease | 5 (56)2 | 1 (17)3 | |

| Jaundice | 3 (33) | 4 (67) | |

| Weight loss | 6 (67) | 6 (100) | |

| in kilograms | 8.5 (3-12) | 15.5 (8-50) | 0.030 |

| Location of lesion (head of the pancreas) | 8 (89) | 5 (83) | |

| Ca 19-9 (normal range 0-27 kU/L) | 35.2 (2.5-300) | 89.8 (19.8-110) |

1 × IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, 1 × IgG4-related sialadenitis, 1 × Crohn's disease, 1 × Autoimmune thyroiditis;

2 × Chronic pancreatitis, 3 × Acute pancreatitis;

1 × Chronic pancreatitis. Quantitative data are expressed as median (range), qualitative data as absolute values with percentages. AIP: Autoimmune pancreatitis; PC: Pancreatic cancer.

Table 2.

Histopathology findings in patients with type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis + pancreatic cancer

| Patient | Sex | Age | Periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate without granulocytic infiltration | Obliterative phlebitis | Storiform fibrosis | IgG4-positive cells |

| 2 | M | 67 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 47/HPF |

| 6 | M | 61 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 58/HPF |

HPF: High-power field.

Table 3.

Histopathology findings in patients with type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis + pancreatic cancer

| Patient | Sex | Age | Granulocytic infiltration of duct wall (GEL) | Granulocytic and lymphoplasmacytic acinar infiltrate | IgG4-positive cells |

| 1 | M | 54 | Yes | 4/HPF | |

| 3 | M | 63 | Yes | 2/HPF | |

| 4 | M | 58 | Yes | 7/HPF | |

| 5 | M | 60 | Yes | 4/HPF |

HPF: High-power field.

Six patients with AIP had a history of pancreatic disease - three had chronic pancreatitis (two with AIP and one with AIP + PC), and three patients with AIP alone had experienced an acute episode of pancreatitis of unspecified etiology. Four patients with AIP and none with AIP + PC had a history of other autoimmune diseases. Two patients with AIP type 1 had an involvement of other organs (IgG4-sclerosing cholangitis and sialadenitis) manifesting during postsurgical follow-up. One patient with AIP type 1 had autoimmune thyroiditis, and one patient with AIP type 2 had a history of Crohn’s disease.

In eleven patients (seven with AIP and four with AIP + PC), a fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the pancreatic lesion had been performed. Cytological examination of the aspirates from the AIP + PC patients was true positive in three and inconclusive in one. In those with AIP, the examination was true negative in four patients, false-positive in two, and inconclusive in one (Table 4).

Table 4.

Serum IgG4, imaging methods and fine needle aspiration biopsy results in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis + pancreatic cancer

| Sex | Age | Serum IgG4 (mg/dL) | CT | ERP | EUS | EUS-FNA | |

| AIP type 1 + PC | M | 67 | N/A | A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| M | 61 | N/A | A | CBD stricture; no wirsungography | Susp M | Inconclusive | |

| AIP type 1 | M | 46 | 81.5 | L2 | CBD stricture; no wirsungography | Ambigious | Negative |

| M | 57 | 81.5 | A | CBD stricture; no wirsungography | N/A | N/A | |

| M | 49 | N/A | A | Unsuccesful attempt for wirsungography | Cystic tumour; signs of CHP | Inconclusive | |

| M | 48 | 23.1 | L2 | N/A | Susp M | Negative | |

| AIP type 2 + PC | M | 54 | NR | L2 | N/A | Ambigious | Susp M |

| M | 63 | NR | A | N/A | Ambigious | Susp M | |

| M | 58 | NR | A | Wirsungolithiasis | N/A | N/A | |

| M | 60 | NR | A | N/A | Ambigious | Susp M | |

| AIP type 2 | F | 61 | NR | L2 | N/A | Susp M | Susp M |

| F | 64 | NR | A | Dilated PD; mucous secretion | Susp MD-IPMN | Negative | |

| M | 35 | NR | L2 | N/A | ambigious | Susp M | |

| F | 47 | NR | L2 | N/A | ambigious | Negative | |

| M | 53 | NR | A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

L2: Level 2 evidence of parenchymal imaging according to ICDC criteria; M: Male; F: Female; NR: Not relevant; N/A: Results not available or examination not done; A: Atypical-finding not suggestive of AIP; susp M: Findings suspected of malignancy; CHP: Chronic pancreatitis; CBD: Common bile duct; PD: Pancreatic duct; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasonography; EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy; CT: Computed tomography; AIP: Autoimmune pancreatitis; PC: Pancreatic cancer.

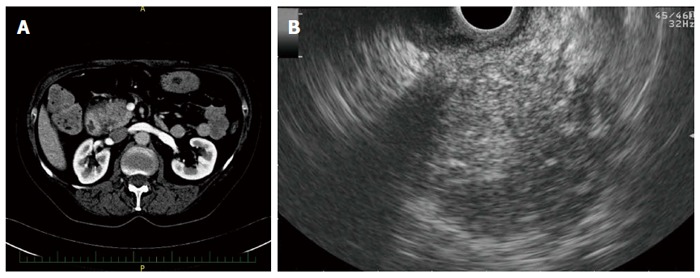

Knowing the final histological diagnosis, we retrospectively evaluated the medical histories, imaging findings, and laboratory results of patients with AIP + PC to assess the possibility of preoperative diagnosis of AIP using the current consensus criteria. None of the patients would have met the ICDC criteria preoperatively. Serum levels of IgG4 were not determined in the two patients with AIP type 1, and histology was not obtained in any of the AIP type 2 patients. Only one patient (with AIP type 2) had a CT finding suggestive of AIP, however malignant elements were found in the FNAB cytology. In the remaining five patients the CT findings would not have raised suspicion of AIP. Preoperative findings in both groups are shown in Table 4, Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Imaging findings in a patient with autoimmune pancreatitis. A: Hypodense lesion in the pancreatic head on computed tomography; B: Hypoechoic lesion of the pancreatic head on endoscopic ultrasonography.

Figure 3.

Imaging findings in a patient with autoimmune pancreatitis + pancreatic cancer. A: Hypodense lesion in the pancreatic head with a common bile duct (CBD) stent on computed tomography; B: Distal CBD stricture on endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography.

DISCUSSION

AIP and PC may present with similar manifestations, but have very different treatments. Typically, an older patient presents with abdominal pain and obstructive jaundice caused by a focal pancreatic lesion. If AIP is diagnosed, the mainstay of treatment is immunosuppression using corticosteroids, usually resulting in rapid regression of the expansion and alleviation of symptoms. This therapy spares the patient from a challenging surgical procedure associated with high morbidity and considerable mortality. On the other hand, if pancreatic cancer is the cause of symptoms, the only chance for survival is prompt surgical treatment. Such clinical cases represent a complex diagnostic dilemma. Precise differential diagnosis of AIP and PC is essential for the right treatment and prognosis of patients, but is sometimes extremely difficult, if not impossible, to determine. Serum markers of AIP (notably serum IgG4) are often helpful in diagnosis of both conditions[12]. However, IgG4 levels exceeding twice the upper limit of normal were found in a considerable proportion of patients with pancreatic cancer and thus this marker cannot be used alone to exclude the diagnosis of malignancy[13]. In cases where the presence of pancreatic cancer cannot be ruled out with certainty, pancreatic resection is indicated. The aim of our study was to evaluate the proportion of AIP in all patients undergoing resection for a suspected tumor. The finding of AIP in 5% of all resections in our patient series is in agreement with previously published data. The occurrence of AIP in patients resected for a suspected tumor has been shown to be around 6%-8%[11]. This high number reflects the similar presentation of both diseases and the difficult diagnostic algorithm of AIP.

The relatively high proportion of patients with type 2 AIP (60%) in our series might be explained by a higher prevalence of this subtype in our geographic region as well as more frequent presentation of type 2 AIP as a focal pancreatic lesion[14-16]. In addition, recognition of this subtype in the absence of a serological marker and extrapancreatic manifestations is more challenging. It can thus be assumed that this subtype will be found more often in patients with unrecognized AIP, and will not precisely match the characteristics of AIP patients in the general population.

An intriguing finding in our study is the high incidence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in patients with AIP, which reached 40%. In our opinion, this represents the largest ever published group of patients with co-occurrence of PC and AIP. Pancreatic cancer in patients with AIP has so far been documented only in individual cases[13,17-20]. Recently, two patients with both AIP and PC were described in a study that examined serum IgG4 level in 106 patients with histologically confirmed pancreatic cancer[13]. None of our patients was diagnosed with AIP or had ever been given immunosuppressive therapy before surgery. A retrospective analysis of all available data revealed that our AIP patients would not have met the ICDC criteria preoperatively. However, the diagnostic algorithm was not complete in any of them, as they were referred for surgery with an already established diagnosis of suspected pancreatic cancer. Nevertheless, it needs to be emphasized that some of our patients had been resected many years ago before AIP was thoroughly described and the ICDC criteria proposed.

Diagnosis of AIP accompanying PC based on histology is a major drawback of our study. We are aware that the nonspecific peritumoral pancreatitis adjacent to pancreatic neoplasms might share some histologic features with AIP type 1, i.e., by abundance of IgG4+ plasma cells, venulitis or periductal inflammation[21]. However, distribution of IgG4+ plasma cells in nonspecific peritumoral pancreatitis was shown to be patchy, in contrary to diffuse infiltration which is described in AIP[22,23]. All cases of AIP + PC were reviewed by a pathologist specialized in pancreatic diseases. Only cases with diffuse distribution of IgG4+ plasma cells (density > 50/HPF) and with the presence of all morphologic features of AIP type 1 were included in the study. This cutoff was shown to provide an excellent specificity in distinguishing AIP type 1 and peritumoral pancreatitis[21]. In AIP type 2 the granulocytic epithelial lesions were nosognostic for the disease.

The relationship between AIP and PC is poorly understood although several different explanations were formulated. The first one considers AIP as a precursor for pancreatic cancer due to chronic inflammation which leads to harboring of mutations and, over time, to development of cancer. Chronic pancreatitis is a well-known risk factor of pancreatic cancer, increasing the risk of cancer development by as much as 13.3-fold[24]. The cumulative risk of developing pancreatic cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis is estimated to be 4%[25]. A similar association in patients with AIP has not yet been demonstrated. However, in line with the case reports of pancreatic cancer in patients with AIP mentioned above, there are data that indirectly support this assumption. For example, Gupta et al[26] in a retrospective analysis of resected tissue of AIP patients, found a higher prevalence of premalignant lesions, i.e., pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN 1-2), in patients with AIP compared with patients with otherwise nonspecified chronic pancreatitis. In addition, they noted development of pancreatic cancer in two of 84 patients with AIP during a prospective 49-mo follow-up period. The high frequency of K-ras mutations found in pancreatic tissue of patients with AIP further supports the association of the two diseases[27].

Higher incidence of pancreatic cancer has scarcely been reported in prospectively followed cohorts of patients with AIP[28]. However, population studies are usually limited by a small number of patients due to the low incidence of the disease and also by short follow-up periods. Furthermore, prospectively followed patients with AIP are usually adequately treated with immunosuppression, unlike patients with unrecognized AIP or with pancreatitis of other etiologies. In such a scenario, one might speculate that suppression of inflammatory activity may reduce the risk of malignancy development in a similar way to that seen in inflammatory bowel disease[29]. An increased incidence of pancreatic cancer would then be expected in untreated patients or in those with an insufficient response to immunosuppressive treatment. Duration of follow-up is also an important factor. If patients with chronic pancreatitis of other etiologies develop pancreatic cancer, then it is usually in the interval of one to two decades after chronic pancreatitis is diagnosed[25]. There are patients suffering for years from unrecognized AIP in the absence of cardinal symptoms such as jaundice or typical radiological findings. Recently published data suggest that up to one third of patients with AIP can develop signs typical of advanced chronic pancreatitis of other etiologies (e.g., parenchymal atrophy or calcifications)[30,31].

Another consideration proposes AIP type 1 as a paraneoplastic phenomenon. This hypothesis is based on observation of a significantly higher incidence of malignancy in patients with IgG4-RD within the first year of follow-up compared to subsequent years[32,33]. The explanation would be that occult cancer may alter cell-mediated immunological responses and thus create an inflammatory environment favorable for onset of autoimmune disease - in this case AIP type 1 or any other IgG4-RD. However, these initial observations from Japanese authors were not further supported by western studies[34,35].

Despite the small number of patients in our study, we found three major differences between patients with AIP and AIP + PC, with one of them being statistically significant. The significantly higher age of patients with AIP + PC may be somewhat expected due to the mechanism of cancer development, presumed to be a long-term chronic inflammatory process. It is consistent with the concept of pancreatic cancer being a late complication of chronic pancreatitis, much like colorectal cancer being a late complication of ulcerative colitis. The higher proportion of recent onset diabetes in patients with AIP + PC compared with patients with AIP only is an interesting finding. Diabetes mellitus has been reported in 42%-78% of patients at the onset of AIP, however it persisted in only 10% of the AIP patients following corticosteroid treatment of the acute inflammation[36]. In our study, recent-onset diabetes was present in only 11% patients with AIP. New onset diabetes mellitus as a symptom of pancreatic cancer has been documented in numerous studies[37]. However, its use in the differential diagnosis of cancer and chronic pancreatitis is difficult, because diabetes is a common complication of advanced chronic pancreatitis of non-autoimmune etiology. In our study only six patients without PC had weight loss as opposed to all patients with PC. Weight loss in patients with AIP and PC was much greater than in those who had AIP without PC (15.5 kg vs 8.5 kg, P = 0.03). Even though exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and weight loss are not uncommon in patients with AIP[38], a severe weight loss should raise suspicion for a possible presence of pancreatic cancer.

The possible synchronous occurrence of AIP and PC implies major clinical consequences. Our data indicate that distinguishing these two entities becomes even more challenging, as the preoperative diagnosis of AIP does not rule out pancreatic cancer. Even patients with an established diagnosis of AIP must thus be treated and followed with caution.

A shortcoming of our study, beyond its small size and retrospective nature, is the fact that the selection of patients was based on histological examination of resected tissue. Our hospital is a tertiary center that performs many resections as a service for regional gastroenterology facilities. Consequently, the opportunity to change the diagnostic algorithm, which is often not fully completed, is sometimes limited. Finally, the natural course of pancreatic cancer is so unfavorable that all our patients have already died. Consequently, they could not be revaluated.

Autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer may have similar presentations and their distinction is often difficult. We evaluated all patients who underwent pancreatic resection for a focal pancreatic enlargement and found that a considerable proportion of the resected patients had autoimmune pancreatitis. Furthermore, we found that some patients with autoimmune pancreatitis also had pancreatic cancer, demonstrating the eventuality of synchronous presence of PC in patients with proven AIP. Our results show that those with AIP and cancer were older, more likely to have recent-onset diabetes and had a greater weight loss than those with AIP only. Definitive confirmation of these initial observations will require additional prospective studies with a larger number of patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a distinct form of chronic pancreatitis characterized by specific clinical, laboratory, radiological and histological findings. AIP may mimic pancreatic cancer (PC), as it often presents with obstructive jaundice and focal pancreatic enlargement.

Research frontiers

Due to similar manifestation of AIP and PC, a lot of attention was given to the differentiation of the two conditions, as the precise differential diagnosis is essential for the right treatment and prognosis of patients. However, because the diagnosis of AIP is complex, many AIP patients undergo unnecessary surgery rather than immunosuppressive treatment. Chronic inflammatory process is a well-known risk factor of malignancy, as described in chronic pancreatitis and PC. A similar association in patients with AIP and PC has been suggested but not demonstrated. There are only a few cases of PC in AIP patients reported in the literature.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In the presented study, we show that a considerable proportion of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for a cancer suspicion may have AIP. However, we also showed that patients with AIP may have synchronous presence of pancreatic cancer. Those with AIP and PC were older, have been more often recently diagnosed with diabetes, and have experienced a greater weight loss than those without PC. The presented group of patients with PC and AIP co-occurrence is, to our knowledge, the largest ever published.

Applications

The possible synchronous occurrence of AIP and PC implies major consequences, as diagnosing AIP in a patient with focal pancreatic enlargement may not rule out the presence of pancreatic cancer. The knowledge of characteristics distinguishing the two groups of patients might aid in the differential diagnosis.

Terminology

Pancreatic cancer is usually an adenocarcinoma derived from pancreatic ductal cells; autoimmune pancreatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory disease of the pancreas defined by a combination of the following features: frequent presentation with obstructive jaundice accompanied with diffuse or focal organ swelling, rapid response to steroids, as well as by histological finding of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and fibrosis of the pancreas. Based on laboratory results, clinical profiling and histology, it is classified into type 1 and type 2.

Peer-review

“Simultaneous occurrence of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in patients resected for focal pancreatic mass” is an interesting paper.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Czech Republic

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee with multi-center competence of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) and Thomayer Hospital (TN).

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no financial relationship to disclose.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: December 29, 2016

First decision: January 10, 2017

Article in press: March 2, 2017

P- Reviewer: Castanon MS, Gonzalez-Ojeda A, Lin J, Manenti A, Pezzilli R S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Nishimori I, Tamakoshi A, Otsuki M. Prevalence of autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan from a nationwide survey in 2002. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 18:6–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2043-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanno A, Nishimori I, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hirota M, Kuriyama S, Tsuji I, Shimosegawa T. Nationwide epidemiological survey of autoimmune pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas. 2012;41:835–839. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182480c99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickartz T, Mayerle J, Lerch MM. Autoimmune pancreatitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:314–323. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Mino-Kenudson M, Kim MH, Klöppel G, Lerch MM, Löhr M, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas. 2011;40:352–358. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182142fd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klöppel G, Lüttges J, Löhr M, Zamboni G, Longnecker D. Autoimmune pancreatitis: pathological, clinical, and immunological features. Pancreas. 2003;27:14–19. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Naruse S, Tanaka S, Nishimori I, Ohara H, Ito T, Kiriyama S, Inui K, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria of autoimmune pancreatitis: revised proposal. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:626–631. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KP, Kim MH, Kim JC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune chronic pancreatitis revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2487–2496. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Vege SS, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1010–106; quiz 934. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sah RP, Chari ST. Autoimmune pancreatitis: an update on classification, diagnosis, natural history and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frulloni L, Scattolini C, Falconi M, Zamboni G, Capelli P, Manfredi R, Graziani R, D’Onofrio M, Katsotourchi AM, Amodio A, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: differences between the focal and diffuse forms in 87 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2288–2294. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugumar A, Chari S. Autoimmune pancreatitis: an update. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:197–204. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morselli-Labate AM, Pezzilli R. Usefulness of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis and follow up of autoimmune pancreatitis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:15–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bojková M, Dítě P, Dvořáčková J, Novotný I, Floreánová K, Kianička B, Uvírová M, Martínek A. Immunoglobulin G4, autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis. 2015;33:86–90. doi: 10.1159/000368337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart PA, Kamisawa T, Brugge WR, Chung JB, Culver EL, Czakó L, Frulloni L, Go VL, Gress TM, Kim MH, et al. Long-term outcomes of autoimmune pancreatitis: a multicentre, international analysis. Gut. 2013;62:1771–1776. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, Sugumar A, Clain JE, Levy MJ, Pearson RK, Smyrk TC, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:140–148; quiz e12-13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamisawa T, Chari ST, Giday SA, Kim MH, Chung JB, Lee KT, Werner J, Bergmann F, Lerch MM, Mayerle J, et al. Clinical profile of autoimmune pancreatitis and its histological subtypes: an international multicenter survey. Pancreas. 2011;40:809–814. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182258a15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghazale A, Chari S. Is autoimmune pancreatitis a risk factor for pancreatic cancer? Pancreas. 2007;35:376. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318073ccb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukui T, Mitsuyama T, Takaoka M, Uchida K, Matsushita M, Okazaki K. Pancreatic cancer associated with autoimmune pancreatitis in remission. Intern Med. 2008;47:151–155. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loos M, Esposito I, Hedderich DM, Ludwig L, Fingerle A, Friess H, Klöppel G, Büchler P. Autoimmune pancreatitis complicated by carcinoma of the pancreatobiliary system: A case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2011;40:151–154. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f74a13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandrasegaram MD, Chiam SC, Nguyen NQ, Ruszkiewicz A, Chung A, Neo EL, Chen JW, Worthley CS, Brooke-Smith ME. A case of pancreatic cancer in the setting of autoimmune pancreatitis with nondiagnostic serum markers. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:809023. doi: 10.1155/2013/809023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhall D, Suriawinata AA, Tang LH, Shia J, Klimstra DS. Use of immunohistochemistry for IgG4 in the distinction of autoimmune pancreatitis from peritumoral pancreatitis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deshpande V, Chicano S, Finkelberg D, Selig MK, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge WR, Colvin RB, Lauwers GY. Autoimmune pancreatitis: a systemic immune complex mediated disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1537–1545. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213331.09864.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Notohara K, Levy MJ, Chari ST, Smyrk TC. IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:23–28. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg A, Domellöf L. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Morselli-Labate AM, Maisonneuve P, Pezzilli R. Pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis; aetiology, incidence, and early detection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta R, Khosroshahi A, Shinagare S, Fernandez C, Ferrone C, Lauwers GY, Stone JH, Deshpande V. Does autoimmune pancreatitis increase the risk of pancreatic carcinoma?: a retrospective analysis of pancreatic resections. Pancreas. 2013;42:506–510. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31826bef91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamisawa T, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Horiguchi S, Hayashi Y, Yun X, Yamaguchi T, Sasaki T. Frequent and significant K-ras mutation in the pancreas, the bile duct, and the gallbladder in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2009;38:890–895. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b65a1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikeura T, Miyoshi H, Uchida K, Fukui T, Shimatani M, Fukui Y, Sumimoto K, Matsushita M, Takaoka M, Okazaki K. Relationship between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a single-center experience. Pancreatology. 2014;14:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maire F, Le Baleur Y, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Couvelard A, Voitot H, Sauvanet A, Hentic O, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, et al. Outcome of patients with type 1 or 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:151–156. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruyama M, Watanabe T, Kanai K, Oguchi T, Asano J, Ito T, Ozaki Y, Muraki T, Hamano H, Arakura N, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis can develop into chronic pancreatitis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:77. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiokawa M, Kodama Y, Yoshimura K, Kawanami C, Mimura J, Yamashita Y, Asada M, Kikuyama M, Okabe Y, Inokuma T, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:610–617. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asano J, Watanabe T, Oguchi T, Kanai K, Maruyama M, Ito T, Muraki T, Hamano H, Arakura N, Matsumoto A, et al. Association Between Immunoglobulin G4-related Disease and Malignancy within 12 Years after Diagnosis: An Analysis after Longterm Followup. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2135–2142. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hart PA, Law RJ, Dierkhising RA, Smyrk TC, Takahashi N, Chari ST. Risk of cancer in autoimmune pancreatitis: a case-control study and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2014;43:417–421. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huggett MT, Culver EL, Kumar M, Hurst JM, Rodriguez-Justo M, Chapman MH, Johnson GJ, Pereira SP, Chapman RW, Webster GJ, et al. Type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis is associated with extrapancreatic organ failure, malignancy, and mortality in a prospective UK cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1675–1683. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimori I, Tamakoshi A, Kawa S, Tanaka S, Takeuchi K, Kamisawa T, Saisho H, Hirano K, Okamura K, Yanagawa N, et al. Influence of steroid therapy on the course of diabetes mellitus in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: findings from a nationwide survey in Japan. Pancreas. 2006;32:244–248. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202950.02988.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pannala R, Basu A, Petersen GM, Chari ST. New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:88–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buijs J, Cahen DL, van Heerde MJ, Rauws EA, de Buy Wenniger LJ, Hansen BE, Biermann K, Verheij J, Vleggaar FP, Brink MA, et al. The Long-Term Impact of Autoimmune Pancreatitis on Pancreatic Function, Quality of Life, and Life Expectancy. Pancreas. 2015;44:1065–1071. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]