Key Points

Integrin PSI domain has endogenous thiol-isomerase function.

Novel anti-β3 PSI antibodies inhibit PDI-like activity and platelet adhesion/aggregation, and have antithrombotic therapeutic potential.

Abstract

Integrins are a large family of heterodimeric transmembrane receptors differentially expressed on almost all metazoan cells. Integrin β subunits contain a highly conserved plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) domain. The CXXC motif, the active site of the protein-disulfide-isomerase (PDI) family, is expressed twice in this domain of all integrins across species. However, the role of the PSI domain in integrins and whether it contains thiol-isomerase activity have not been explored. Here, recombinant PSI domains of murine β3, and human β1 and β2 integrins were generated and their PDI-like activity was demonstrated by refolding of reduced/denatured RNase. We identified that both CXXC motifs of β3 integrin PSI domain are required to maintain its optimal PDI-like activity. Cysteine substitutions (C13A and C26A) of the CXXC motifs also significantly decreased the PDI-like activity of full-length human recombinant β3 subunit. We further developed mouse anti-mouse β3 PSI domain monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that cross-react with human and other species. These mAbs inhibited αIIbβ3 PDI-like activity and its fibrinogen binding. Using single-molecular Biomembrane-Force-Probe assays, we demonstrated that inhibition of αIIbβ3 endogenous PDI-like activity reduced αIIbβ3-fibrinogen interaction, and these anti-PSI mAbs inhibited fibrinogen binding via different levels of both PDI-like activity-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Importantly, these mAbs inhibited murine/human platelet aggregation in vitro and ex vivo, and murine thrombus formation in vivo, without significantly affecting bleeding time or platelet count. Thus, the PSI domain is a potential regulator of integrin activation and a novel target for antithrombotic therapies. These findings may have broad implications for all integrin functions, and cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions.

Introduction

Integrins are primary mediators of cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion, and play key roles in diverse fundamental biological processes, including embryo development, cell migration and differentiation, tumorigenesis, inflammation and immune response, atherosclerosis, hemostasis, and thrombosis.1-3 The integrin αIIbβ3 is essential for platelet adhesion and aggregation during hemostasis,3-6 and defects in αIIbβ3 may cause severe hemorrhage.7,8 Conversely, inappropriate platelet and integrin αIIbβ3 activation (such as at sites of atherosclerotic plaque rupture) may lead to thrombosis and myocardial infarction or stroke, the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide.9,10

To date, 24 distinct members of the heterodimeric integrin superfamily have been identified, assembled from 18 α and 8 β subunits.1 Integrins exist in several switchable conformations, ranging from a bent low-affinity state to an extended high-affinity ligand-binding state.2,3 These conformational changes are regulated by their extracellular regions, transmembrane domains, and cytoplasmic tails,11-16 and by the bidirectional “inside-out” and “outside-in” signals, which regulate cell function.1,2,17-19

Although significant progress has been made to understand integrin biology, the biochemical basis of the allosteric movements and mechanisms of integrin activation remain to be further elucidated. It has been suggested that cysteine-derived thiol/disulfide groups of the β subunit are implicated in the conformational rearrangements.11,12,20,21 Disruption of disulfide bonds in the plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI), epidermal-growth-factor (EGF), and β-tail domains affect activation states of αIIbβ3.22-24 Disulfide bond remodeling in a physiologic context is mediated primarily by thiol-isomerases, such as protein-disulfide-isomerase (PDI), ERp5, and ERp57.25-27 This oxidoreductase activity is derived from active CXXC thioredoxin motifs. Through both intra- and intermolecular disulfide bond exchanges, these thiol-isomerases play a critical role in the post-translational modification and stabilization of newly synthesized proteins as well as maintenance of their structure and biological functions.18,21 It has been observed that thiol-isomerases secreted to the platelet surface after platelet activation play a role in the activation of αIIbβ3.28-33 Interestingly, endogenous thiol-isomerase (PDI-like) activity of αIIbβ3 has also been reported,34 though the exact origin of this endogenous enzymatic activity and its role in integrin conformational switches have yet to be uncovered.

The PSI domain, a 54-amino-acid sequence located near the N-terminus of the β subunit, is highly conserved across the integrin family and species, suggesting an essential role in integrin function. The location of this domain, at the “knee” region of the integrin in association with the hybrid domain, may be particularly significant during integrin conformational changes.11,35-37 The functionality of the PSI domain to β3 integrin has been alluded to in studies in which a polymorphism at residue 33 may induce generation of alloantibodies that cause thrombocytopenias and bleeding disorders.38,39 This polymorphism predisposes to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.40 Interestingly, the PSI domain contains 7 cysteine residues, which have been implicated in restraining β2-integrin activation.41,42 Furthermore, substitution of residue Cys435, which abolishes the covalent link to Cys13 in the PSI domain,41 resulted in a constitutively active, ligand-binding conformation of αIIbβ3.24 However, to date the precise role of the PSI domain in integrins, along with its 7 cysteines residues, is largely unknown.

In the present study, we demonstrated that integrin PSI domain has endogenous thiol-isomerase activity. We developed β3 PSI domain–specific mouse anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which cross-react with platelets from humans and other species tested. These mAbs inhibited the thiol-isomerase activity of αIIbβ3 and αIIbβ3-fibrinogen interaction and, importantly, inhibited platelet adhesion/aggregation in vitro and thrombus formation in murine models without significantly affecting bleeding time or platelet count. These findings reveal the potential of β3 PSI domain as a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of thrombotic diseases. Because the PSI domain is highly conserved across the integrin family and different species, this discovery may significantly advance our understanding of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, as well as provide insights into multiple human diseases and future therapies.

Methods

All animal studies were approved by the Animal Care Committee, and all experimental procedures using human blood samples were approved by the Research Ethics Board, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Cloning and expression of PSI domain recombinant proteins of murine β3, human β1, and β2 integrins

Plasmids coding for glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-murine β3 PSI domain and its mutants were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). The mutants were generated by mutating cysteines in CXXC motifs: C13S/C16S (mutant 1) or C23S/C26S (mutant 2), or in both C13S/C16S/C23S/C26S (double-mutant [DM]). The GST-fusion proteins were purified with a GSTrap column (GE Healthcare, QC, Canada).43 Human β1- and β2-integrin PSI domain recombinant proteins (rPSI) were generated by inserting respective cDNA fragments into the same pGEX-4T-1 vectors (Thermo Scientific) for expression.

Cloning and expression of full-length human β3-integrin recombinant proteins

Plasmid coding for full-length human β3-integrin subunits was subcloned into a modified pEF-IRES-puro vector that fused to C-terminal segments containing 6×His tag. Full-length human β3 plasmids were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis for cysteine substitutions (C13A and C26A in β3 PSI domain). Constructs were transfected into HEK 293 cells and proteins were purified as previously described.44

Thiol-isomerase function assay

Thiol-isomerase activity was measured as previously described,34 with minor modifications. Briefly, reduced/denatured RNase (rdRNase; 1-10 µg) was incubated with PDI or the PSI recombinant proteins (± preincubation with anti-PSI mAb, bacitracin or 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) for 2 hours at room temperature, or the mutants in 0.1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM EDTA, overnight at room temperature. Then cytidine 2’,3′-cyclic monophosphate (0.1 mg/mL in 0.1 M 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) was added and absorbance was measured at 284 nm.

Incorporation of Na-(3-maleimidylpropionyl)-biocytin into rdRNase

The Na-(3-maleimidylpropionyl)-biocytin (MPB) incorporation was performed as previously described.45 Briefly, the wild-type or double-mutant full-length β3 (0.50 µM) was incubated with rdRNase (2 µg/mL) followed by labeling MPB (100 µM) for 30 minutes at room temperature. All reactions were performed in 20 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 0.14 M NaCl buffer, pH 7.4. The biotinylated proteins were detected by western blotting with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP).

Monoclonal antibody generation and characterization

Mouse anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies against β3-integrin PSI domain were generated from β3-deficient (β3−/−) mice immunized with rPSI as previously described,46,47 and characterized using flow cytometry, western blotting, and immunoprecipitation.

Biomembrane-Force-Probe detection of fibrinogen-αIIbβ3 integrin interactions

Biomembrane-Force-Probe (BFP) was performed as previously described.48,49 Briefly, the target (αIIbβ3-bearing bead) and the probe (fibrinogen-bearing bead) were repeatedly brought into contact with a ∼15 pN compressive force for a known contact time (tc) (0.1-5 s for adhesion frequency assay) that allowed for bond formation, and then retracted for adhesion detection. Adhesion and nonadhesion events were enumerated to calculate an adhesion frequency in 50 cycles for each probe-target pair. Three to five probe-target pairs were measured to render an average adhesion frequency (Pa) at each tc. The two-dimensional (2D) effective on-rate (mrmlAckon) and 2D off-rate (koff) can be derived by fitting the Pa vs tc curve with a previously established model, where mr and ml are the surface densities of receptors and ligands, respectively, which are constants in all BFP experiments given that the same batch of integrin and fibrinogen beads were used.50 Ac is the contact area of the target and probe beads. kon is the 2D on-rate. The 2D effective affinity (mrmlAcKa) is calculated as mrmlAckon/koff.

In vitro platelet aggregation and ex vivo perfusion chamber assays

Platelet aggregometry51,52 and perfusion chamber assays53-55 were performed as previously described, and as detailed in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site. Platelet aggregation was induced by different agonists as indicated. For the perfusion chamber assay, heparinized, fluorescently labeled human or murine whole blood was perfused over a collagen-coated surface at high or low shear rates.

In vivo thrombosis models

The laser-induced intravital microscopy thrombosis model was performed as previously described.52,54-56 Dynamic accumulation of fluorescently labeled platelets within the growing thrombi was captured and analyzed. The FeCl3 (5%)–injured carotid artery thrombosis model was also performed.53,57 The blood flow was monitored by a Doppler flow probe and the time to the cessation of the blood flow was recorded as occlusion time.

Tail bleeding time and platelet count assays

The bleeding time54,56 and platelet count47,58-60 assays were modified from the procedures previously described, and detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired or paired, two-tailed Student t test and one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

Additional materials and methods can be found in the supplemental Data.

Results

Integrin PSI domain has endogenous thiol-isomerase activity

Through analysis of the amino acid sequences of β3 integrin from various species, 2 CXXC motifs were found within the PSI domain. Interestingly, these CXXC sites are not only 100% conserved among different species, but also conserved in all β-integrin subunits. To determine whether integrin PSI domain has endogenous thiol-isomerase function, we generated recombinant murine β3 PSI domain protein (rPSI), as well as human integrin-β1 and -β2 rPSI. Using a reduced/denatured RNase assay, we demonstrated that murine β3 rPSI possesses concentration-dependent thiol-isomerase function, and that this activity was conserved in both human β1 and β2 rPSI (Figure 1A). Similar results were observed in an alternative thiol-isomerase activity (insulin turbidity) assay (supplemental Figure 1A). Notably, we found that the enzymatic activity of β3 rPSI was weaker than PDI (Figure 1B), which may represent its suboptimal structure and enzymatic activity in the recombinant protein.

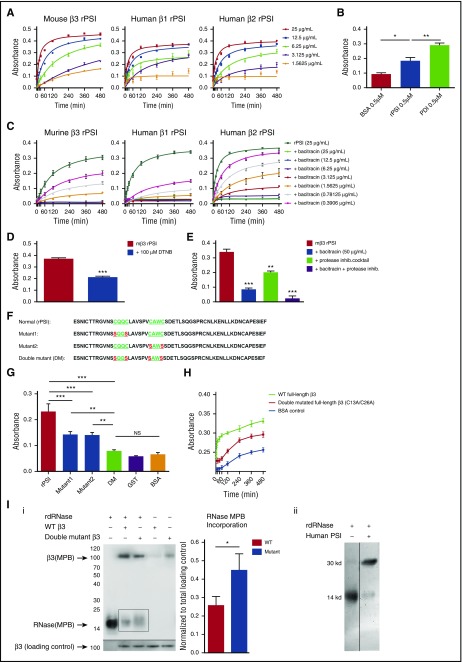

Figure 1.

Integrin PSI domain possesses endogenous thiol-isomerase activity. (A) Recombinant murine β3, human β1, and human β2 PSI domain (rPSI) demonstrated concentration-dependent thiol-isomerase function, as measured by the rdRNase refolding assay. (B) PDI-like function comparison between rPSI and PDI. The rPSI PDI-like activity was lower than PDI. (C) Bacitracin, a thiol-isomerase inhibitor, dose-dependently inhibited thiol-isomerase function of murine β3, human β1, and human β2 rPSI (25 μg/mL). (D) An alternative thiol-isomerase inhibitor, DTNB (100 μM), was used to further confirm the endogenous thiol-isomerase activity of the murine β3 (mβ3) PSI domain. (E) The inhibitory function of bacitracin was maintained in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail. (F) PSI amino-acid sequence analysis highlighting the CXXC motifs and illustrating the substitutions performed on the mutant proteins (red). (G) PSI single mutants (mutant1: C13S/C16S and mutant2: C23S/C26S, 12.5 μg/mL) and PSI double-mutant (DM PSI: C13S/C16S/C23S/C26S, 12.5 μg/mL) showed significantly less thiol-isomerase function compared with murine β3 rPSI. (H) Mutation of a cysteine located in each CXXC motif of the PSI domain (C13A and C26A [DM]) significantly decreased the thiol-isomerase activity of full-length human β3 recombinant protein. Absorbance at 284 nm is shown. (I) Full-length recombinant β3 integrin and human PSI domain catalyzed the formation of new disulfide bonds, induced rdRNase refolding, and decreased MPB incorporation into rdRNase: full-length wild-type or DM (C13A/C26A) β3 subunit (i), or recombinant human PSI domain (ii) was incubated with rdRNase, followed by incubation with MPB (100 μM) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The excess MPB was quenched by reduced glutathione (200 μM) for 30 minutes, and excess glutathione was quenched by iodoacetamide (400 µM) for 10 minutes at room temperature. The MPB-incorporated proteins were run on 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in nonreducing conditions. After transfer, the biotinylated proteins were detected by western blotting with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The figure is representative of 3 individual experiments. The square marks the area for density analysis of MPB in rdRNase with wild-type or DM full-length β3 integrin. Densitometry analysis showed a significant difference (P < .05) of MPB incorporation to rdRNase between wild-type and DM β3 integrin.

We found that bacitracin, a universal thiol-isomerase inhibitor, dose-dependently inhibited PDI-like function in rPSI (Figure 1C), and in purified αIIbβ3 integrin (supplemental Figure 1B). Furthermore, an alternative thiol-isomerase inhibitor, DTNB, also inhibited the thiol-isomerase activity of murine β3 rPSI (Figure 1D). To exclude the possibility of protease activity derived from bacitracin contaminants affecting our observations, we demonstrated that the thiol-isomerase inhibitory function of bacitracin was preserved in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Figure 1E and supplemental Figure 1C).

Both CXXC motifs are required for optimal thiol-isomerase activity of integrin PSI domain and full-length β3 integrin

We first generated 3 mutant murine β3 rPSI proteins lacking specific cysteine residues. A mutation of cysteines in either of the CXXC motifs—C13S/C16S (mutant 1) or C23S/C26S (mutant 2) (Figure 1F)—markedly decreased the thiol-isomerase function (Figure 1G). In the DM, thiol-isomerase activity was completely abolished (Figure 1G). To further assess the significance of the CXXC motifs in the whole integrin β subunit, we generated full-length human-β3-subunit recombinant protein in which both CXXC motifs of the PSI domain were mutated (C13A and C26A). We found that the thiol-isomerase activity of this mutated β3 subunit was significantly decreased (Figure 1H). To confirm the thiol-isomerase function of β3 PSI, we measured the incorporation of MPB into rdRNase to directly demonstrate disulfide bond shuffling/exchange. Our data showed that there was significantly less MPB incorporated into rdRNase after incubation with wild-type, full-length β3 recombinant protein, compared with the DM (C13A/C26A) (Figure 1Ii). MPB incorporation into rdRNase in the presence of the DM was less than rdRNase alone, indicating that thiol-isomerase activity is present in other domains. Furthermore, we confirmed that recombinant human β3 PSI catalyzed the formation of new disulfide bonds and decreased MPB incorporation in rdRNase (Figure 1Iii). These findings clearly demonstrated that the PSI domain and other domains of β3 integrin possess thiol-isomerase activity.

Thiol-isomerase inhibitors decreased ligand binding to purified αIIbβ3 integrin

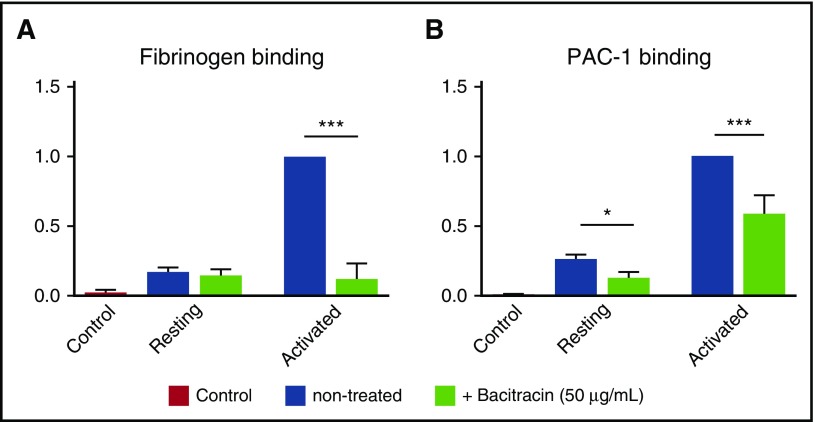

To elucidate whether endogenous thiol-isomerase activity affects integrin activation and ligand binding affinity, we examined the effects of bacitracin on the binding of fibrinogen and PAC-1 (a mAb that recognizes active human αIIbβ3 integrin) to purified human platelet β3 integrins, in a cell-free enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We found that bacitracin significantly decreased fibrinogen and PAC-1 binding to activated human β3 integrin (Figure 2A-B), and this effect is not caused by the direct interaction between bacitracin and fibrinogen or PAC-1 because no binding signal was observed in an ELISA with bacitracin-coated wells (supplemental Figure 1D). These data are consistent with earlier reports in β3 and other integrins,32,33,61 demonstrating that endogenous PDI-like activity of β3 integrin is important for integrin conformational changes, leading to integrin activation and ligand binding.

Figure 2.

Bacitracin, a thiol-isomerase inhibitor, inhibited αIIbβ3 activation of fibrinogen and PAC-1 binding. Fibrinogen and PAC-1 binding to activated human αIIbβ3 was inhibited by bacitracin. (A) Fibrinogen and bacitracin were added into a Mn2+-activated, purified, native human αIIbβ3 integrin precoated ELISA plate. After washing in PBS, anti-fibrinogen antibody was added, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. o-Phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) substrate was added and absorbance was measured at 492 nm. (B) PAC-1 and bacitracin were added into a Mn2+-activated, purified, native human αIIbβ3 integrin precoated ELISA plate. After washing in PBS, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was added. OPD substrate was added and absorbance was measured at 492 nm. Mean ± SEM; *P < .05, ***P < .001, n = 4-6 each.

Anti-β3 PSI monoclonal antibodies bind specifically to β3 integrin PSI domain and inhibit its PDI-like activity

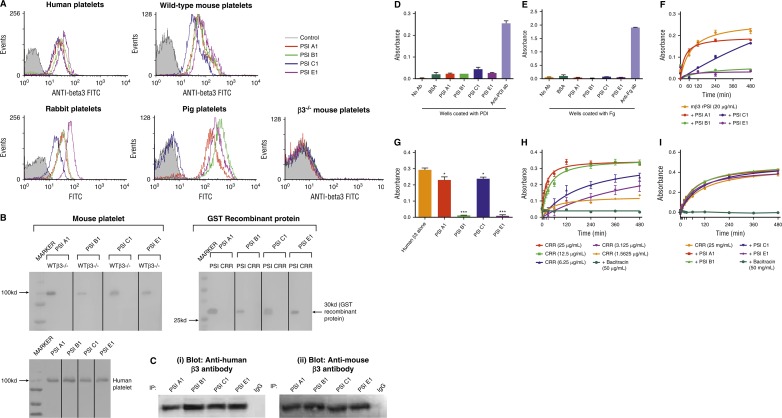

To further examine the role of the PSI domain in integrins, particularly β3 integrin in relation to its role in hemostasis and thrombosis, we generated 4 unique mouse anti-mouse mAbs against the PSI domain of β3 integrin: PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1. Using flow cytometry, we demonstrated that these antibodies bound to wild-type murine platelets, along with human, porcine, and rabbit platelets tested, but did not bind to murine β3−/− platelets (Figure 3A). These data indicate the specificity of the mAbs for β3 integrin and excluded the prospect of mAbs binding to other integrin β-subunits (eg, α2β1, α5β1, α6β1, α8β1 integrins) or other CXXC motif-containing proteins expressed on the platelet surface. Binding of the anti-PSI domain mAbs to human platelets was blocked by murine β3 rPSI, further confirming the specificity of the anti-PSI mAbs for the integrin PSI domain (supplemental Figure 2). Western blotting and immunoprecipitation demonstrated that these mAbs bound only to the β3 PSI domain but did not bind to other domains in the cysteine-rich region (CRR) of the β3-subunit (Figure 3B-C), ERp57, or β2 integrins (supplemental Figure 3). We also demonstrate that the mAbs do not cross-react with PDI or fibrinogen, using ELISA assay (Figure 3D-E). Because our mAbs can cross-react with β3 PSI domain from other species, these novel anti-PSI mAbs will be useful for animal models (eg, pigs, mice, rabbits) of different human diseases, including cardiovascular diseases.

Figure 3.

Anti-β3 PSI domain antibodies bind specifically to the PSI domain of β3 integrin. (A) Flow cytometry demonstrated that anti-β3 PSI mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) bound to β3 on platelets: wild-type or β3−/− murine platelets, human, pig, or rabbit platelets were incubated with PBS (control) or anti-PSI mAbs followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-mouse IgG. The binding was tested using flow cytometry. (B) The mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) recognize the linear epitope of β3-integrin PSI domain. The recombinant PSI domain or the lysates from wild-type or β3−/− platelet were loaded into a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in reducing conditions. After electrophoresis and transfer, the polyvinylidene fluoride membrane was cut and each strip was incubated with a different anti-PSI mAb, as indicated in the figure, followed by alkaline phosphatase (AP) or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. The binding was detected by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate-toluidine salt/nitro blue tetrazolium–purple liquid (for AP) or chemiluminescent substrate following manufacturers’ instructions. (C) Immunoprecipitation further demonstrated that anti-mouse β3 PSI domain mAbs specifically bound the β3-integrin PSI domain. The anti-PSI mAbs were used for the immunoprecipitation and the commercial anti-human (i) or anti-mouse β3 integrin (ii) antibodies were used for the western blot. NIT G, an anti-GPIb mAb, was used as a negative IgG control. 1 × 108 platelets were used. (D-E) Anti-PSI mAbs did not bind PDI (D) or fibrinogen (E). ELISA plate wells were coated with PDI (1 μg/mL) or fibrinogen (0.1 μg/mL) overnight. After blocking with bovine serum antigen (1 μg/mL) for 1 hour, anti-PSI mAbs (1 μg/mL), anti-PDI antibody (positive control), or anti-fibrinogen antibody (positive control) was added and incubated for 1.5 hours at 37°C. After addition of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, substrate was added and absorbance was measured at 492 nm. (F) Anti-PSI mAbs significantly inhibited mouse β3-integrin recombinant PSI thiol-isomerase function (mean ± SEM; absorbance after 480 minutes from different groups was compared; PSI A1 and PSI C1 vs rPSI: P < .05; PSI B1 and PSI E1 vs rPSI: P < .01; n = 3 each). (G) Anti-PSI mAbs (5 μg/mL) inhibited purified native human β3-integrin (40 μg/mL) thiol-isomerase function (mean ± SEM; *P < .05, ***P < .001; n = 3). (H-I) Anti-PSI mAbs did not inhibit CRR PDI-like activity. CRR has endogenous PDI-like activity (H). CRR was incubated with or without anti-PSI mAbs (5 μg/mL) followed by adding rdRNase overnight. The PDI-like activity was measured using rdRNase assay.

To further characterize these anti-PSI mAbs and their epitopes, we performed competitive binding assays using rPSI or mutants (mutant 1 [C13S/C16S], mutant 2 [C23S/C26S], or the DM). We demonstrated that neither mutant 1 nor the DM inhibited binding of our anti-PSI mAbs to platelets (supplemental Figure 4). Conversely, mutant 2 significantly decreased the binding of PSI A1, PSI C1, and PSI E1, to levels almost comparable with nonmutated rPSI (supplemental Figure 4i,iii,iv). These results suggest that the presence of an intact C13XXC16 motif is critical for these 3 mAbs to bind to the PSI domain of αIIbβ3 on platelets. In the case of PSI B1, neither mutant 1, mutant 2, nor the DM had any significant effect on its binding to platelets (supplemental Figure 4ii). These data demonstrated that PSI B1 binds to β3 PSI domain depending on both CXXC motifs, suggesting a unique epitope for this antibody.

To investigate the effects of our anti-PSI mAbs on the thiol-isomerase activity of the β3 PSI domain, murine β3 rPSI was incubated with anti-PSI mAbs, then incubated with rdRNase overnight and, subsequently, RNase refolding was measured. We found that mAbs PSI B1 and PSI E1 abrogated PDI-like function of the PSI domain (Figure 3F). MAbs PSI A1 and PSI C1 reduced the thiol-isomerase activity of murine β3 rPSI, albeit to a lesser extent (Figure 3F). Consistently, both PSI B1 and PSI E1 strongly inhibited the thiol-isomerase activity of purified human native β3 integrin, and PSI A1 and PSI C1 significantly (but to a lesser extent) reduced this activity (Figure 3G). Our mAbs had no effect on the thiol-isomerase activity of CRR recombinant protein, indicating that our mAbs do not cross-react with other CXXC containing proteins (Figure 3H-I). These anti-PSI mAbs did not inhibit the thiol-isomerase activity of β1 or β2 rPSI (data not shown), further demonstrating their specificity for β3 PSI domain.

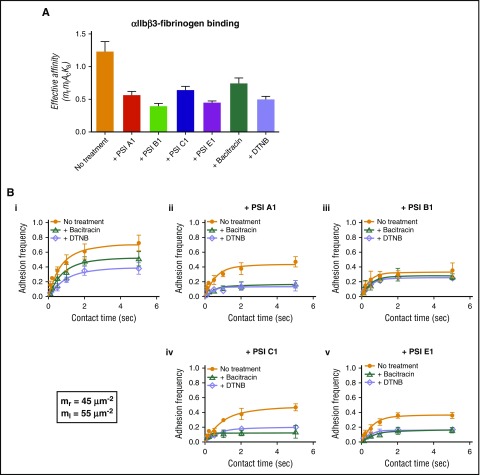

Anti-PSI mAbs significantly inhibited fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 in single-molecular BFP assays

To determine whether our anti-PSI mAbs affected fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3, we used the BFP assay. This allowed us to detect fibrinogen-αIIbβ3 interactions and the binding force. We first showed that bacitracin and DTNB inhibited fibrinogen binding, which is consistent with our ELISA data (Figure 2A) and suggests that the endogenous αIIbβ3 PDI-like function is important for its ligand binding. We also found that these anti-PSI mAbs significantly inhibited αIIbβ3-fibrinogen interactions (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Anti-PSI mAbs inhibited fibrinogen binding to purified human integrin αIIbβ3 as demonstrated by BFP technique. (A) A αIIbβ3-bearing bead and fibrinogen-bearing bead were repeatedly brought into contact with a ∼15 pN compressive force for 0.1-5 seconds, which allowed for bond formation, and was then retracted for adhesion detection. The effective affinity (mrmlAcKa) of αIIbβ3-fibronogen binding fitted and calculated from BFP adhesion frequency curves. (B) BFP detection of fibrinogen-αIIbβ3 binding in a purified system. BFP “Adhesion frequency vs Contact Time” plots integrin αIIbβ3 binding to fibrinogen. The experiments were performed in the absence of (orange) or presence of bacitracin (green) or DTNB (purple). (i-v) The antibodies PSI A1 (ii), PSI B1 (iii), PSI C1 (iv), or PSI E1 (v) were added into the experimental environment, respectively. The site densities of αIIbβ3 (mr) and fibrinogen (ml) are marked in the lower left corner. Mean ± SEM; *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n = 4.

To elucidate whether the decreased fibrinogen binding is caused by the inhibition of thiol-isomerase activity or a direct effect on αIIbβ3 conformational changes, we used bacitracin and DTNB, in combination with our anti-PSI mAbs in the BFP assays. We found that mAbs (PSI A1, PSI C1, or PSI E1) in combination with thiol-isomerase inhibitors (bacitracin or DTNB) decreased fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 more than either mAbs or thiol-isomerase inhibitors alone (Figure 4Bi,ii,iv,v). These data suggested that both inhibition of thiol-isomerase activity and mAb-blocked conformational changes synergistically attenuated the fibrinogen binding, and mAbs can further decrease αIIbβ3-fibrinogen binding beyond the thiol-isomerase activity (ie, steric hindrance of αIIbβ3-fibrinogen binding).

The mAbs PSI B1 and PSI E1 have significantly stronger anti–thiol-isomerase activity than PSI A1 and PSI C1 (Figure 3F-G); consistently, they have stronger inhibitory effect on αIIbβ3-fibrinogen interaction (Figure 4ABiii,v), suggesting that anti–thiol-isomerase activity partially contributed to their inhibitory effect. Interestingly, unlike PSI E1 as well as PSI A1 and PSI C1, the addition of bacitracin/DTNB did not further enhance the inhibitory effect of PSI B1 (Figure 4Biii), suggesting that PSI B1 binding not only blocks thiol-isomerase derived from the PSI domain itself but likely also inhibits the thiol-isomerase activities of other domains via intramolecular interactions. These data suggest that our anti-PSI mAbs exert their inhibitory effects via both thiol-isomerase activity–dependent and –independent mechanisms (ie, steric hindrance).

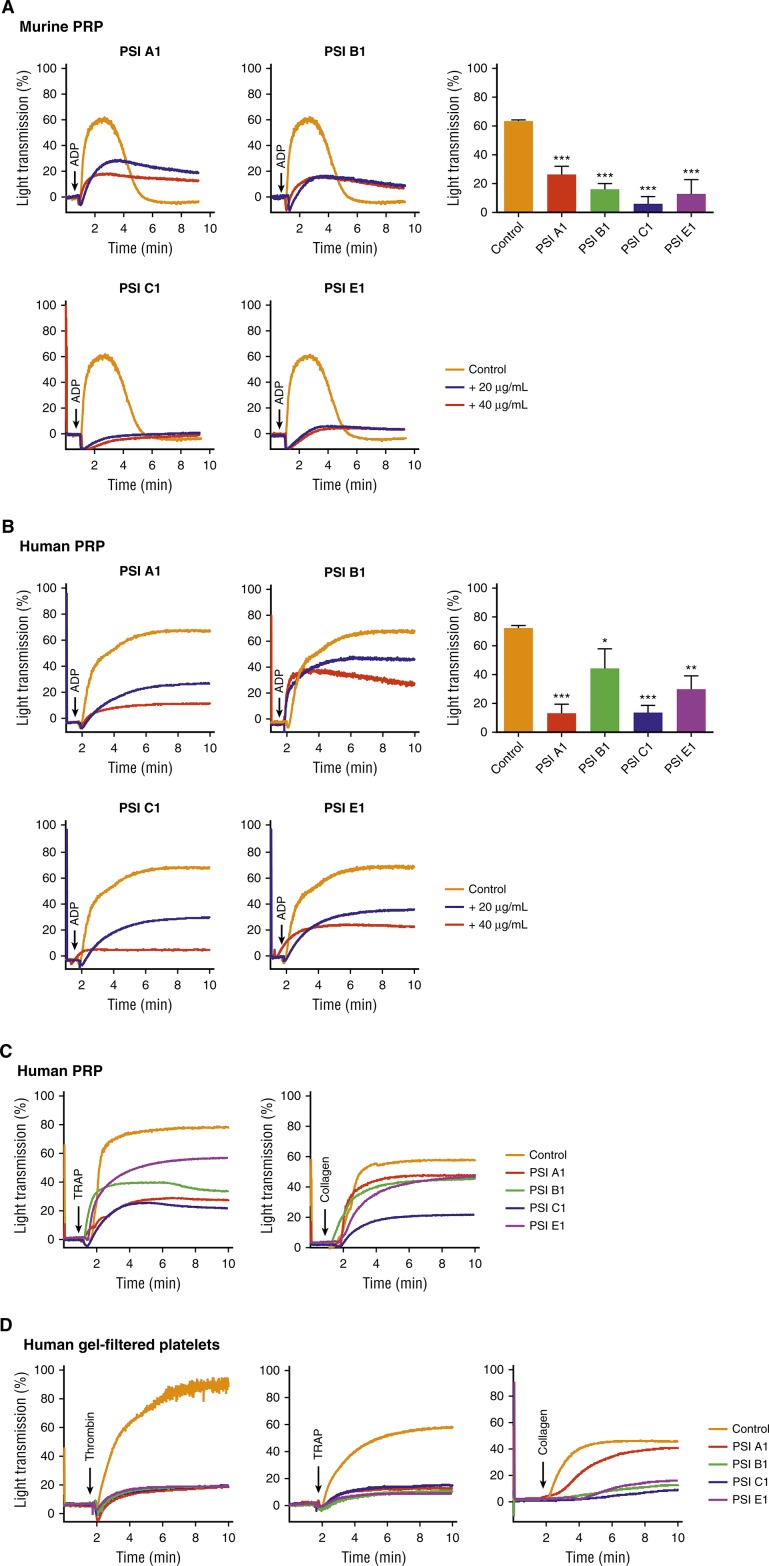

Anti-β3 PSI mAbs inhibited murine and human platelet aggregation in vitro and thrombus formation ex vivo

We performed studies to assess the role of anti-β3 PSI domain mAbs in platelet function. We found that platelet aggregation in both murine and human platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or gel-filtered platelets was significantly attenuated by all 4 anti-PSI mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) after stimulation with various agonists including adenosine diphosphate (ADP), collagen, thrombin, and thrombin receptor–activating peptide (TRAP) (Figure 5A-D). We observed that the inhibitory effect of these anti-PSI mAbs was not dependent on FcγRII because no significant difference was observed in the absence or presence of the Fcγ receptor blocker, IV.3. We also did not find a significant difference (supplemental Figure 5) between phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and IgG isotype control.

Figure 5.

Anti-β3 PSI domain monoclonal antibodies inhibited platelet aggregation in vitro. Murine or human PRP or gel-filtered platelet (2.5 × 108/mL) was incubated with anti-PSI mAb. Platelet aggregation was induced by agonist and monitored using aggregometer. (A) Anti-PSI mAbs (40 μg/mL) inhibited ADP (20 μM)-induced aggregation of murine PRP. (B) Anti-PSI mAbs also inhibited ADP (5 μM)-induced aggregation of human PRP. (C) Anti-PSI mAbs inhibited TRAP (250 μM) and collagen (10 μg/mL)-induced aggregation of human PRP (representative of n = 3-4). (D) Anti-PSI mAbs inhibited thrombin (1 U/mL), TRAP (250 μM), and collagen (10 μg/mL)–induced human gel-filtered platelet aggregation (representative of n = 3-4). Mean ± SEM; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

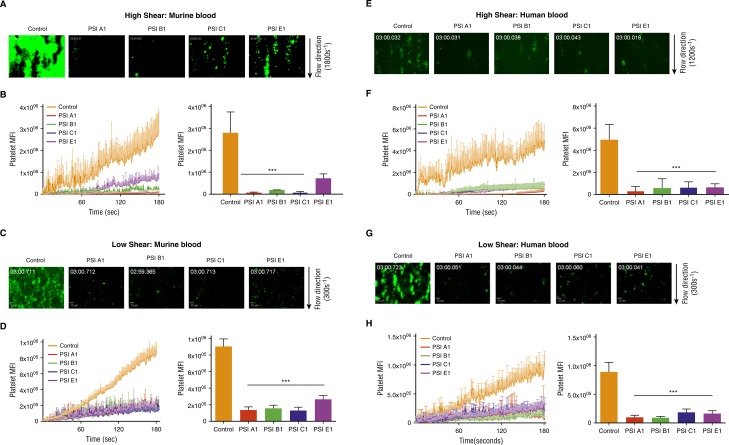

A perfusion chamber thrombosis model was used to evaluate whether anti-PSI mAbs affect thrombus formation under flow conditions. After perfusion over a collagen-coated surface, anti–PSI mAb pretreatment of murine blood dramatically inhibited platelet adhesion, aggregation, and thrombus growth at both high (1800s−1) and low (300s−1) shear (Figure 6A-D). Similar results were also observed with human blood at both high (1200s−1) and low (300s−1) shear (Figure 6E-H). Thus, these in vitro and ex vivo experiments clearly demonstrated that anti-PSI mAbs targeting the β3 PSI domain are significant inhibitors of thrombosis.

Figure 6.

Anti-β3 PSI mAbs inhibited thrombus formation in ex vivo perfusion chambers. Antibodies against PSI domain (10 μg/mL) were incubated with fluorescently labeled human or murine platelets and perfused over a collagen-coated surface (100 μg/mL). (A) Representative images at 3 minutes of murine platelets that were untreated (Control) or incubated with anti-PSI mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) (high shear: 1800s−1). (B) Pretreatment with anti-PSI mAbs inhibited murine platelet adhesion and thrombus formation at a shear rate of 1800s−1 (equivalent to flow in stenotic vessels) (mean ± SEM; ***P < .001 [at 3 min]; n = 3 each). (C) Representative images at 3 minutes of murine platelets that were untreated (Control) or incubated with anti-PSI mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) (low shear: 300s−1). (D) Pre-treatment with anti-PSI mAbs inhibited murine platelet adhesion and thrombus formation at a shear rate of 300s−1 (mean ± SEM; ***P < .001 [at 3 min]; n = 3 each). (E) Representative images at 3 minutes of human platelets that were untreated (control) or incubated with anti-PSI mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) (high shear: 1200s−1). (F) Pretreatment with anti-PSI mAbs inhibited human platelet adhesion and thrombus formation at a shear rate of 1200s−1 (equivalent to flow in stenotic vessels) (mean ± SEM; ***P < .001 [at 3 min]; n = 3 each). (G) Representative images at 3 minutes of human platelets that were untreated (Control) or incubated with anti-PSI mAbs (PSI A1, PSI B1, PSI C1, and PSI E1) (low shear: 300s−1). (H) Pretreatment with anti-PSI mAbs inhibited human platelet adhesion and thrombus formation at a shear rate of 300s−1 (mean ± SEM; ***P < .001 [at 3 min]; n = 3 each).

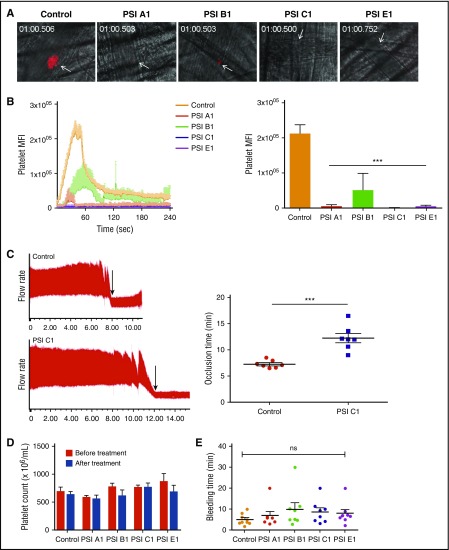

Anti-β3 PSI mAbs inhibited thrombosis in both small and large murine vessels in vivo

We used a laser-injury cremaster arteriole intravital microscopy model to quantitatively examine the effects of our anti-PSI mAbs on thrombosis. Consistent with our in vitro and ex vivo data, IV infusion of our anti-PSI mAbs (but not PBS or isotype control) markedly inhibited thrombosis (Figure 7A-B and supplemental Figure 6). To test the antithrombotic effect in large arteries, a carotid artery thrombosis model was used and vessel occlusion time after FeCl3 injury was also significantly postponed after treatment with a representative anti-PSI domain mAb, PSI C1 (Figure 7C). We confirmed that this observed inhibition of thrombosis and delayed vessel occlusion was not caused by the anti-PSI mAbs inducing platelet clearance or thrombocytopenia (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Anti-β3 PSI mAbs inhibited thrombus formation in in vivo murine thrombosis models without significantly affecting tail bleeding time and platelet counts. C57 mice were injected anti-PSI mAbs before injury. Thrombus formation was monitored and recorded using a computerized digital camera. (A) Representative images showing that thrombosis was induced by a laser injury to the cremaster arterioles. In untreated mice (Control), thrombi reached their maximal size ∼40 seconds after injury. (B) IV injection with anti-PSI mAbs (5 μg in 100 μL saline) 30 minutes before injury significantly inhibited thrombus formation and growth (mean ± SEM; ***P < .001; n = 3 each). (C) FeCl3 injury in a carotid artery thrombosis model. PSI C1 (5 μg in 100 μL saline) pretreatment inhibited carotid artery thrombus formation. Left panel: representative tracing of carotid artery flow after FeCl3 injury. Arrows indicate the time of vessel occlusion. Right panel: statistical analysis of vessel occlusion time (mean ± SEM; **P < .01; n = 7). (D) Anti-PSI mAbs did not induce a significant platelet clearance. Mice were injected with saline or anti-PSI mAbs or anti-native β3 mAbs (5 μg in 100 μL saline). Platelet count was checked 40 minutes after injection (mean ± SEM; NS; n = 3). This result is different from other anti-β3 polyclonal or monoclonal antibody (eg, JAN D1. 9D2 or M1; supplemental Figure S7)–induced platelet clearance.46 (E) Anti-PSI mAbs did not significantly increase tail bleeding time. Mice were injected with anti-PSI mAbs (5 μg in 100 μL saline). Forty minutes after treatment, the bleeding times of each group were compared (mean ± SEM; NS; n = 8-9).

Anti-β3 PSI mAbs did not significantly affect bleeding time and platelet count

Injection of effective dose (5 µg/mouse) of these anti-PSI antibodies did not prolong bleeding time, as evaluated by surgical tail transection (Figure 7E). Importantly, we also did not find a significant decreased platelet count at 40 minutes or 24 hours post-injection, which is markedly different from other anti-β3 integrin antibodies (supplemental Figure 7). These data suggest that these anti-PSI mAbs may have the potential to be developed as safe and effective antithrombotic agents.

Discussion

In this study, we have clearly demonstrated that integrin-β3 PSI domain contains endogenous thiol-isomerase activity, which can be inhibited by bacitracin, DTNB, and our anti–β3 PSI mAbs. We have also shown that, consistent with the highly conserved nature of the amino acid sequence of the integrin PSI domain, this endogenous isomerase function is conserved across different species and integrin-β subunits. We have demonstrated that mutation of the CXXC motifs of the β3 PSI domain abolishes the thiol-isomerase activity of the PSI domain, as well as markedly decreases the thiol-isomerase activity of the entire β3 subunit. Using ELISA and the single-molecular technique BFP, we clearly showed that inhibition of the endogenous PDI-like function significantly reduced fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3. Furthermore, we identified the PSI domain as a novel target for antithrombotic therapy because our newly developed anti-PSI mAbs inhibit the thiol-isomerase activity of β3 PSI domain, block fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3, and abrogate platelet adhesion, aggregation, and thrombus formation in vitro and in both arterioles and larger arteries in vivo.

There are redox-active CXXC motifs present in other domains in the cysteine-rich region of integrin-β subunits such as the hybrid domain and the EGF domains. However, in the current study, we demonstrated that our anti-PSI mAbs specifically recognize β3 PSI domain, although their sensitivities to the mutations of PSI domain CXXC motif vary (supplemental Figure 4). These mAbs do not recognize other regions in β3 integrins, different integrins on platelets or leukocytes, or thiol-isomerases (PDI or ERp57) tested (Figure 3 and supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, the effect of these mAbs is attributed to their specific interactions with β3 PSI domain. The following information suggests that their anti–thiol-isomerase function is part of their effect on αIIbβ3. These include: (1) inhibition of endogenous thiol-isomerase activity by bacitracin or DTNB decreased the binding of fibrinogen or PAC-1 to αIIbβ3 (Figure 2A-B and Figure 4A-B); (2) the thiol-isomerase function of PSI domain is an important part of the enzymatic activity of the entire β3 subunit (Figure 1H-I) that can be inhibited by these mAbs, which is consistent with the antiplatelet effects of these mAbs; and (3) the stronger the anti–thiol-isomerase activities by these mAbs, the stronger the inhibitory effect on αIIbβ3-fibrinogen binding in the pure BFP assays (Figure 4A-B). However, these anti-PSI mAbs can further inhibit αIIbβ3-fibrinogen interaction in the presence of sufficient concentrations of bacitracin or DTNB (Figure 4A-B), suggesting that these mAbs can also affect αIIbβ3 conformation beyond the thiol-isomerase activity (ie, both thiol-isomerase activity-dependent and -independent [steric hindrance] pathways).

It has been shown that disruption of disulfide bonds in the β3 PSI domain may affect its interaction with EGF domains and affect integrin functionality.23,24 Our BFP data for PSI B1 also suggest that completely or severely abolished thiol-isomerase function in PSI domain may affect the PDI-like activities in other regions (Figure 4A-B). Therefore, the thiol-isomerase activity of the PSI domain may be critical in the regulation of intramolecular interactions (eg, the hybrid and EGF domains), at the knee region of the integrin controlling the “swing-out” mechanism involved in integrin activation. This enzymatic activity may also be a key regulator of intermolecular interactions between integrins and integrin-associated proteins, along with other proteins present on the platelet surface, including thiol-isomerases and coagulation factors.30,62 Furthermore, this PSI domain thiol-isomerase activity leading to integrin conformational changes may induce intraplatelet signaling cascades triggering the secretion of additional platelet thiol-isomerases and enhancing platelet activation and thrombus formation.

PDI inhibitors have been proposed as a potential novel class of antithrombotics.63 However, because of the widespread distribution of PDI in the body, such therapies may result in off-target effects.64,65 Previous studies have shown that antibodies against PDI can cross-react with other PDI-like proteins, such as ERp5730; however, our anti-β3 PSI mAbs, interacting specifically with the β3 PSI domain, are likely able to reduce the clinical side effects. Furthermore, in our mouse models, treatment with the anti-PSI mAbs did not cause significant platelet clearance compared with other mAbs targeting integrin β3, and did not significantly prolong bleeding times. Notably, thrombosis is a complex multifactorial process, involving various cell types, including leukocytes and endothelial cells.5,6,66 Such cells also express integrins, and targeting the PSI domain of other β subunits may also have antithrombotic potential.

In addition to thrombosis, integrins are required for mediating interactions between almost all cells and their extracellular matrix components and are thus implicated in a diverse range of pathologic conditions such as tumorigenesis and metastasis, inflammation, atherosclerosis, and the entire process of thrombosis and macrophage-platelet interactions/embolus clearance.67-72 Targeting integrins is widely recognized and accepted as a potential therapy; however, to date, only a very limited number of integrin antagonists have achieved pharmacologic approval.73,74 Therefore, revealing the role of integrin PSI domains may not only be a considerable advance in the treatment of platelet-derived cardiovascular diseases but could also be a significant contribution to the general cell biology field and facilitate the exploitation of integrins as therapeutic targets for a wide range of conditions.

In summary, we have revealed the endogenous thiol-isomerase activity of the highly conserved PSI domain of the integrin family and uncovered a role for PSI domain in integrin activation and subsequent platelet function. Our novel mAbs inhibited this PDI-like activity of the PSI domain of β3 integrin, as well as platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Importantly, these processes were inhibited without significantly increasing platelet clearance and prolonging bleeding times. These findings not only demonstrate the antithrombotic therapeutic potential of the anti-β3 PSI domain mAbs, but also further elucidate the complex mechanisms of integrin activation. Because the CXXC motifs of the PSI domain are completely conserved across all integrin-β subunits and species, our discoveries should also have broad implications for the greater cell biology field, and may advance the treatment of multiple human diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Barry S. Coller (The Rockefeller University, New York) and Bruce Furie (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Massachusetts) for their valuable comments during this manuscript preparation, F. Patrick Ross (The Ohio State University, Ohio) for the generous gift of murine β3 integrin cDNA, and Reid C. Gallant and Alexandra H. Marshall (Keenan Research Center, St. Michael’s Hospital) for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP# 97918, MOP# 119540), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Ontario), and Canadian Foundation for Innovation; a National Natural Science Foundation of China grant (No. 31371163); and Fundamental Research Funds for the Shenzhen of China (GJHZ201404221516216). N.C. is a recipient of The Canadian Blood Services Postdoctoral Fellowship; M.X. is a recipient of State Scholarship Fund from China Scholarship Council and Ontario Trillium Scholarship, Canada; Y.W. is a recipient of Graduate Fellowship from Canadian Blood Services and Meredith & Malcolm Silver Scholarship in Cardiovascular Studies; X.R.X. is a recipient of the Heart and Stroke/Richard Lewar Centre of Excellence Studentship award and Meredith & Malcolm Silver Scholarship in Cardiovascular Studies; and Y.C. and C.Z. were supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI-044902).

Footnotes

Presented in part orally at the 2012 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology; 2013 Congress of International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis; Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology Scientific Sessions 2014; Platelets 2014–the 8th International Symposium; and highlights in plenary of 2015 Congress of International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: G.Z. planned and carried out experiments, analyzed data, and prepared manuscript; Q.Z. and E.C.R. carried out experiments, analyzed data, and prepared manuscript; N.C. carried out experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to preparation of the manuscript; Y.C. carried out the BFP experiments and analyzed data; X.R.X. carried out experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to preparation of the manuscript; M.X., Y.W., Y.H., L.M., Y.L., M.R., T.N.P.-P., C.L., T.W.S., X.L., and R.A. carried out experiments; P.C. designed and prepared recombinant proteins and mutants; C.Z. provided key equipment and analyzed data; J.A.W. analyzed data and contributed to preparation of the manuscript; R.O.H. provided the key β3−/− mice and valuable comments during the manuscript preparation; J.F. provided key equipment, analyzed data, and contributed to preparation of manuscript; and H.N. supervised the research, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Integrin β3 anti-PSI monoclonal antibodies are patented in the United States, Canada, and Europe (United States Patent Application No. 12/082 686; Canadian Patent application No. 2 628 900; European Patent Application No. 08153880.3).

Correspondence: Qing Zhang, Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510275, P.R. China; e-mail: lsszq@mail.sysu.edu.cn; and Heyu Ni, Canadian Blood Services Centre for Innovation, and Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, St. Michael's Hospital, University of Toronto, Room 421, LKSKI-Keenan Research Centre, 209 Victoria St, Toronto, ON M5B 1W8, Canada; e-mail: nih@smh.ca.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni H, Freedman J. Platelets in hemostasis and thrombosis: role of integrins and their ligands. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2003;28(3):257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bledzka K, Smyth SS, Plow EF. Integrin αIIbβ3: from discovery to efficacious therapeutic target. Circ Res. 2013;112(8):1189-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Gallant RC, Ni H. Extracellular matrix proteins in the regulation of thrombus formation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23(3):280-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu XR, Zhang D, Oswald BE, et al. . Platelets are versatile cells: new discoveries in hemostasis, thrombosis, immune responses, tumor metastasis and beyond. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2016;53(6):409-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurden AT, Fiore M, Nurden P, Pillois X. Glanzmann thrombasthenia: a review of ITGA2B and ITGB3 defects with emphasis on variants, phenotypic variability, and mouse models. Blood. 2011;118(23):5996-6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Andrews M, Yang Y, et al. . Platelets in thrombosis and hemostasis: old topic with new mechanisms. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12(2):126-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reheman A, Xu X, Reddy EC, Ni H. Targeting activated platelets and fibrinolysis: hitting two birds with one stone. Circ Res. 2014;114(7):1070-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ni H, Li A, Simonsen N, Wilkins JA. Integrin activation by dithiothreitol or Mn2+ induces a ligand-occupied conformation and exposure of a novel NH2-terminal regulatory site on the beta1 integrin chain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(14):7981-7987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan B, Smith JW. A redox site involved in integrin activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(51):39964-39972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkins JA, Li A, Ni H, Stupack DG, Shen C. Control of beta1 integrin function. Localization of stimulatory epitopes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(6):3046-3051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shandler SJ, Korendovych IV, Moore DT, et al. . Computational design of a β-peptide that targets transmembrane helices. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(32):12378-12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim C, Ye F, Hu X, Ginsberg MH. Talin activates integrins by altering the topology of the β transmembrane domain. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(5):605-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malinin NL, Plow EF, Byzova TV. Kindlins in FERM adhesion. Blood. 2010;115(20):4011-4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen B, Zhao X, O’Brien KA, et al. . A directional switch of integrin signalling and a new anti-thrombotic strategy. Nature. 2013;503(7474):131-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillson DA, Lambert N, Freedman RB. Formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds in proteins: protein disulfide-isomerase. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:281-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H, Lang S, Zhai Z, et al. . Fibrinogen is required for maintenance of platelet intracellular and cell-surface P-selectin expression. Blood. 2009;114(2):425-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essex DW, Li M. Redox control of platelet aggregation. Biochemistry. 2003;42(1):129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manickam N, Ahmad SS, Essex DW. Vicinal thiols are required for activation of the αIIbβ3 platelet integrin. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(6):1207-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamata T, Ambo H, Puzon-McLaughlin W, et al. . Critical cysteine residues for regulation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 are clustered in the epidermal growth factor domains of the beta3 subunit. Biochem J. 2004;378(Pt 3):1079-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mor-Cohen R, Rosenberg N, Landau M, Lahav J, Seligsohn U. Specific cysteines in beta3 are involved in disulfide bond exchange-dependent and -independent activation of alphaIIbbeta3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(28):19235-19244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun QH, Liu CY, Wang R, Paddock C, Newman PJ. Disruption of the long-range GPIIIa Cys(5)-Cys(435) disulfide bond results in the production of constitutively active GPIIb-IIIa (alpha(IIb)beta(3)) integrin complexes. Blood. 2002;100(6):2094-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen K, Lin Y, Detwiler TC. Protein disulfide isomerase activity is released by activated platelets. Blood. 1992;79(9):2226-2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Essex DW, Li M, Miller A, Feinman RD. Protein disulfide isomerase and sulfhydryl-dependent pathways in platelet activation. Biochemistry. 2001;40(20):6070-6075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jasuja R, Furie B, Furie BC. Endothelium-derived but not platelet-derived protein disulfide isomerase is required for thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2010;116(22):4665-4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holbrook LM, Watkins NA, Simmonds AD, Jones CI, Ouwehand WH, Gibbins JM. Platelets release novel thiol isomerase enzymes which are recruited to the cell surface following activation. Br J Haematol. 2010;148(4):627-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordan PA, Stevens JM, Hubbard GP, et al. . A role for the thiol isomerase protein ERP5 in platelet function. Blood. 2005;105(4):1500-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Ahmad SS, Zhou J, Wang L, Cully MP, Essex DW. The disulfide isomerase ERp57 mediates platelet aggregation, hemostasis, and thrombosis. Blood. 2012;119(7):1737-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Wu Y, Zhou J, et al. . Platelet-derived ERp57 mediates platelet incorporation into a growing thrombus by regulation of the αIIbβ3 integrin. Blood. 2013;122(22):3642-3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson A, O’Neill S, Kiernan A, O’Donoghue N, Moran N. Bacitracin reveals a role for multiple thiol isomerases in platelet function. Br J Haematol. 2006;132(3):339-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahav J, Jurk K, Hess O, et al. . Sustained integrin ligation involves extracellular free sulfhydryls and enzymatically catalyzed disulfide exchange. Blood. 2002;100(7):2472-2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Neill S, Robinson A, Deering A, Ryan M, Fitzgerald DJ, Moran N. The platelet integrin alpha IIbbeta 3 has an endogenous thiol isomerase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(47):36984-36990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao T, Takagi J, Coller BS, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432(7013):59-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni H, Wilkins JA. Localisation of a novel adhesion blocking epitope on the human beta 1 integrin chain. Cell Adhes Commun. 1998;5(4):257-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honda S, Tomiyama Y, Pelletier AJ, et al. . Topography of ligand-induced binding sites, including a novel cation-sensitive epitope (AP5) at the amino terminus, of the human integrin beta 3 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(20):11947-11954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zdravic D, Yougbare I, Vadasz B, et al. . Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21(1):19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vadasz B, Chen P, Yougbaré I, et al. . Platelets and platelet alloantigens: lessons from human patients and animal models of fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Genes Dis. 2015;2(2):173-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss EJ, Bray PF, Tayback M, et al. . A polymorphism of a platelet glycoprotein receptor as an inherited risk factor for coronary thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(17):1090-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. A novel adaptation of the integrin PSI domain revealed from its crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(39):40252-40254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zang Q, Springer TA. Amino acid residues in the PSI domain and cysteine-rich repeats of the integrin beta2 subunit that restrain activation of the integrin alpha(X)beta(2). J Biol Chem. 2001;276(10):6922-6929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohapatra S, Cao Y, Ni H, Salo D. In pursuit of the “holy grail”: recombinant allergens and peptides as catalysts for the allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy. 1995;50(25 Suppl):37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Q, Zhou YF, Zhang CZ, Zhang X, Lu C, Springer TA. Structural specializations of A2, a force-sensing domain in the ultralarge vascular protein von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(23):9226-9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgess JK, Hotchkiss KA, Suter C, et al. . Physical proximity and functional association of glycoprotein 1balpha and protein-disulfide isomerase on the platelet plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(13):9758-9766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, van der Wal DE, Zhu G, et al. . Desialylation is a mechanism of Fc-independent platelet clearance and a therapeutic target in immune thrombocytopenia. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma L, Simpson E, Li J, et al. . CD8+ T cells are predominantly protective and required for effective steroid therapy in murine models of immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2015;126(2):247-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosetti F, Chen Y, Sen M, et al. . A lupus-associated Mac-1 variant has defects in integrin allostery and interaction with ligands under force. Cell Reports. 2015;S2211-1247(15)00183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, Liu B, Ju L, et al. . Fluorescence biomembrane force probe: concurrent quantitation of receptor-ligand kinetics and binding-induced intracellular signaling on a single cell. J Vis Exp. 2015;(102):e52975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chesla SE, Selvaraj P, Zhu C. Measuring two-dimensional receptor-ligand binding kinetics by micropipette. Biophys J. 1998;75(3):1553-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang H, Reheman A, Chen P, et al. . Fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor-independent platelet aggregation in vitro and in vivo. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(10):2230-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reheman A, Gross P, Yang H, et al. . Vitronectin stabilizes thrombi and vessel occlusion but plays a dual role in platelet aggregation. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(5):875-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y, Shi Z, Reheman A, et al. . Plant food delphinidin-3-glucoside significantly inhibits platelet activation and thrombosis: novel protective roles against cardiovascular diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lei X, Reheman A, Hou Y, et al. . Anfibatide, a novel GPIb complex antagonist, inhibits platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo in murine models of thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111(2):279-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reheman A, Yang H, Zhu G, et al. . Plasma fibronectin depletion enhances platelet aggregation and thrombus formation in mice lacking fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2009;113(8):1809-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Reheman A, Spring CM, et al. . Plasma fibronectin supports hemostasis and regulates thrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4281-4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murphy AJ, Bijl N, Yvan-Charvet L, et al. . Cholesterol efflux in megakaryocyte progenitors suppresses platelet production and thrombocytosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):586-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen P, Li C, Lang S, et al. . Animal model of fetal and neonatal immune thrombocytopenia: role of neonatal Fc receptor in the pathogenesis and therapy. Blood. 2010;116(18):3660-3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li C, Piran S, Chen P, et al. . The maternal immune response to fetal platelet GPIbα causes frequent miscarriage in mice that can be prevented by intravenous IgG and anti-FcRn therapies. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(11):4537-4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ni H, Chen P, Spring CM, et al. . A novel murine model of fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: response to intravenous IgG therapy. Blood. 2006;107(7):2976-2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mou Y, Ni H, Wilkins JA. The selective inhibition of beta 1 and beta 7 integrin-mediated lymphocyte adhesion by bacitracin. J Immunol. 1998;161(11):6323-6329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laurindo FR, Pescatore LA, Fernandes DC. Protein disulfide isomerase in redox cell signaling and homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(9):1954-1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jasuja R, Passam FH, Kennedy DR, et al. . Protein disulfide isomerase inhibitors constitute a new class of antithrombotic agents. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(6):2104-2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karala AR, Ruddock LW. Bacitracin is not a specific inhibitor of protein disulfide isomerase. FEBS J. 2010;277(11):2454-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan MM, Simizu S, Lai NS, Kawatani M, Shimizu T, Osada H. Discovery of a small molecule PDI inhibitor that inhibits reduction of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6(3):245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Darbousset R, Thomas GM, Mezouar S, et al. . Tissue factor-positive neutrophils bind to injured endothelial wall and initiate thrombus formation. Blood. 2012;120(10):2133-2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lievens D, von Hundelshausen P. Platelets in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106(5):827-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu X, Lu D, Scully MF, Kakkar VV. The role of integrin-mediated cell adhesion in atherosclerosis: pathophysiology and clinical opportunities. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(22):2140-2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69(1):11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu XR, Gallant RC, Ni H. Platelets, immune-mediated thrombocytopenias, and fetal hemorrhage. Thromb Res. 2016;141(Suppl 2):S76-S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yougbaré I, Lang S, Yang H, et al. . Maternal anti-platelet β3 integrins impair angiogenesis and cause intracranial hemorrhage. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(4):1545-1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li J, van der Wal DE, Zhu L, et al. . Fc-independent phagocytosis: implications for IVIG and other therapies in immune-mediated thrombocytopenia. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;13(1):50-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu XR, Carrim N, Neves MA, et al. . Platelets and platelet adhesion molecules: novel mechanisms of thrombosis and anti-thrombotic therapies. Thromb J. 2016;14(Suppl 1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cox D, Brennan M, Moran N. Integrins as therapeutic targets: lessons and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(10):804-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]