Abstract

Objective:

Despite high rates of college cannabis use, little work has identified high-risk cannabis use events. For instance, Mardi Gras (MG) and St. Patrick’s Day (SPD) are characterized by more college drinking, yet it is unknown whether they are also related to greater cannabis use. Further, some campuses may have traditions that emphasize substance use during these events, whereas other campuses may not. Such campus differences may affect whether students use cannabis during specific events. The present study tested whether MG and SPD were related to more cannabis use at two campuses with different traditions regarding MG and SPD. Further, given that Campus A has specific traditions regarding MG whereas Campus B has specific traditions regarding SPD, cross-campus differences in event-specific use were examined.

Method:

Current cannabis-using undergraduates (N = 154) at two campuses completed an online survey of event-specific cannabis use and event-specific cannabis-related problems.

Results:

Participants used more cannabis during MG and SPD than during a typical weekday, typical day on which the holiday fell, and a holiday unrelated to cannabis use (Presidents’ Day). Among those who engaged in event-specific use, MG and SPD cannabis use was greater than typical weekend use. Campus differences were observed. For example, Campus A reported more cannabis-related problems during MG than SPD, whereas Campus B reported more problems during SPD than MG.

Conclusions:

Specific holidays were associated with more cannabis use and use-related problems. Observed between-campus differences indicate that campus traditions may affect event-specific cannabis use and use-related problems.

Cannabis use remains high on college campuses. Almost one third of undergraduates report having used in the past year (Kilmer et al., 2006; Mohler-Kuo et al., 2003), and approximately 25% of first-year past-year undergraduate cannabis users meet criteria for a cannabis use disorder (Caldeira et al., 2008). College cannabis use is related to a range of risky behaviors including drinking and driving, other substance use, and risky sex (Bell et al., 1997; Caldeira et al., 2008; Everett et al., 1999; Poulson et al., 2008). Further, cannabis use adversely affects brain development among young adults (Ashtari et al., 2009) and negatively affects memory and motivation (Caldeira et al., 2008; Kouri et al., 1995).

Despite the clear risks associated with college cannabis use, little research has identified high-risk cannabis use situations. Although accumulating evidence indicates that specific events are associated with greater college student drinking (Del Boca et al., 2004; Greenbaum et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2006; Lefkowitz et al., 2012; Neighbors et al., 2011), we know of only three studies testing whether cannabis use increases during specific events. Cannabis use was greater during Spring Break than it was in the month before Spring Break (Ragsdale et al., 2012), 30% of past-year abstainers used cannabis during a music festival (Hesse et al., 2010), and college students did not appear more likely to use cannabis to celebrate Halloween (Miller et al., 1993). However, it remains unclear whether cannabis use increases during other high-risk holidays. Similarly, we know of no studies identifying whether cannabis-related impairment increases during high-risk holidays. Such information could inform treatment and prevention interventions.

Likewise, little research has identified factors related to event-specific cannabis use. Some campuses may have traditions that emphasize substance use during specific holidays, whereas other campuses may not. Such campus differences may affect whether students use cannabis during specific holidays. Mardi Gras (MG) and St. Patrick’s Day (SPD) are holidays related to heavy episodic college drinking (Neighbors et al., 2007), yet we know of no studies examining whether campuses with different holiday traditions differ in their event-specific cannabis use.

The current study sought to fill these gaps. First, we tested whether students, regardless of campus, would report more cannabis use on MG and SPD compared with a typical weekday or weekend day, a typical day of the week on which the holiday occurred, and a holiday not typically characterized by substance use (Presidents’ Day). Second, we compared two campuses with different traditions regarding specific holidays (MG, SPD) on students’ event-specific cannabis use and use-related problems. Campus A is located in southern Louisiana and has specific campus traditions regarding MG, whereas Campus B is located in the Midwest and has specific campus traditions regarding SPD. Thus, these campuses were compared with regard to event-specific cannabis use and use-related problems to test the following: (a) whether Campus A students would report more cannabis use and use-related problems during MG than Campus B whereas Campus B students would report more cannabis use and use-related problems during SPD than those of Campus A, and (b) whether Campus A students reported more cannabis use and use-related problems during MG than SPD and whether Campus B students reported more cannabis use and use-related problems during SPD than MG.

Method

Participants and procedures

The institutional review boards at each campus approved this study, and informed consent was obtained before data collection. Participants were recruited from undergraduate psychology courses and received research credit for their participation. Participants completed an online survey administered via surveymonkey.com from March 31, 2014, to April 30, 2014, soon after the events of interest (MG, SPD). Participants at both campuses completed the same measures.

Eligibility criteria at both sites were identical and included being at least 18 years of age and endorsing cannabis use during the monitoring period. Two participants’ data from Campus A were excluded because of questionable validity (detailed below). Participants reporting greater than 3 SD above the mean for their university’s cannabis use during the timeframe assessed were excluded (Campus A n = 1; Campus B n = 1). The campuses did not differ on the percentage of outliers, χ2(1, n = 154) = 0.40, p = .528. The total sample consisted of 154 (58.4% female) current cannabis users (see Table 1 for demographic information by campus).

Table 1.

Descriptive variables for each campus

| Variable | Campus A (n = 108) M (SD) or % | Campus B (n = 46) M (SD) or % | F or χ2 | p | d or Cramer’s ϕ |

| Age, in years | 20.47 (1.39) | 20.37 (1.29) | 0.18 | .669 | .07 |

| Sex, % male | 29.6 | 69.6 | 21.18 | .000 | .37 |

| Race, % White | 80.6 | 84.8 | 0.39 | .534 | .05 |

| Grade point average | 3.08 (0.48) | 3.14 (0.46) | 0.49 | .487 | .12 |

| % in fraternity/sorority | 37.0 | 23.9 | 2.51 | .113 | .13 |

| Family income, $a | 155,331 (496,249) | 107,717 (147,482) | 0.41 | .525 | .13 |

| Past-month cannabis use frequencyb | 8.81 (8.93) | 5.83 (7.58) | 3.92 | .050 | .36 |

| Past-month drinking frequencyb | 10.03 (8.00) | 10.00 (6.25) | 0.00 | .983 | .00 |

| Tobacco use, % smokers | 28.7 | 17.4 | 2.18 | .140 | .12 |

In U.S. dollars;

number of days in the last 28 days.

Campus A.

Participants were 108 undergraduates from a large public university in southern Louisiana. Mardi Gras (French for “Fat Tuesday”) day is the day before Ash Wednesday. The name refers to the practice of consuming high-calorie food on this Tuesday in preparation for fasting of some religions during Lent, which begins on Ash Wednesday. MG season includes a series of carnival celebrations (characterized by parades, parties, etc.) that take place between the Christian holidays Epiphany (January 6) and MG day. Campus A has several traditions related specifically to MG. The campus’s school colors are thought to have been derived from the colors that characterize MG. Celebrations in the region in which Campus A is located tend to culminate during the last week of the MG season; thus, Campus A suspends classes for 2.5 days the week of MG. Campus A does not suspend classes for SPD.

Campus B.

Participants were 46 undergraduates from a midwestern university. Although Campus B officially begins celebrating SPD 10 days before March 17, approximately 6 months before SPD, students begin selling various memorabilia (e.g., t-shirts) on campus across from a statue of St. Patrick next to a sign counting down the “daze” until SPD. In addition, classes are suspended for the 2 days before SPD. Campus B does not suspend classes for MG.

Measures

Timeline Followback (TLFB).

Each campus received versions of the self-report TLFB (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) on which important campus events, federal holidays (e.g., Presidents’ Day), and other campus (e.g., campus closures) and local (e.g., parades) events specific to each campus were labeled. Each assessment timeframe was from February 1–March 28, 2014, and thus included assessment of MG, SPD, and Presidents’ Day at both campuses. Participants reported the number of “joints” (i.e., cannabis cigarettes as opposed to something cigar-sized or bigger) used per day. The TLFB is considered a reliable and valid self-report measure of cannabis use (O’Farrell et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2014).

Marijuana Problems Scale–Event Specific (MPS-ES).

This measure was adapted from the original MPS (Stephens et al., 2000) for use in this study. The MPS-ES was used to assess 19 negative consequences related to cannabis use during the most recent MG and SPD. Endorsed items were summed to create a total number of cannabis-related problems. The original MPS has demonstrated adequate internal consistency in prior work (e.g., Buckner et al., 2010; Stephens et al., 2000). The MPS-ES demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the present sample (MPS-ES/MG α = .90; MPS-ES/SPD α = .90).

Past-month substance use.

Past-month cannabis use was assessed by asking, “During the last 28 days, on how many days did you use marijuana?” Past-month alcohol use was assessed by asking, “During the last 28 days, on how many days did you have any alcohol to drink?” Past-month tobacco use was assessed by asking, “Have you smoked cigarettes in the past month?”

Infrequency Scale.

To identify responders who provided random or grossly invalid responses, we included four questions from the Infrequency Scale (Chapman & Chapman, 1983). As in prior studies (e.g., Cohen et al., 2009), individuals who endorsed three or more infrequency items were excluded.

Data analytic strategy

First, analyses of variance and chi-square analyses were conducted to determine differences between Campus A and Campus B. Second, results from the Shapiro–Wilk’s Tests of Normality for the outcome variables indicated significantly nonnormal distributions (Wweekday = .66, Wweekend = .82, WMon. = .63, WTues. = .65, WMG = .66, WSPD = .62, WPD = .58, WVD = .76, df = 154, p < .001). Thus, negative binomial regressions with log-link functions were conducted to test whether cannabis use during MG and during SPD was greater than that reported during a typical weekday day, typical weekend day, typical Monday (for SPD, which occurred on a Monday in 2014), typical Tuesday (for MG given that MG occurs on a Tuesday), and Presidents’ Day. Separate models were conducted for each independent variable paired with each dependent variable. Third, negative binomial regressions were used to test whether campuses differed on event-specific use and use-related problems.

Results

Descriptives

Campus A students reported somewhat more past-month cannabis use, and Campus B had a greater percentage of male participants (Table 1).

Event-specific cannabis use

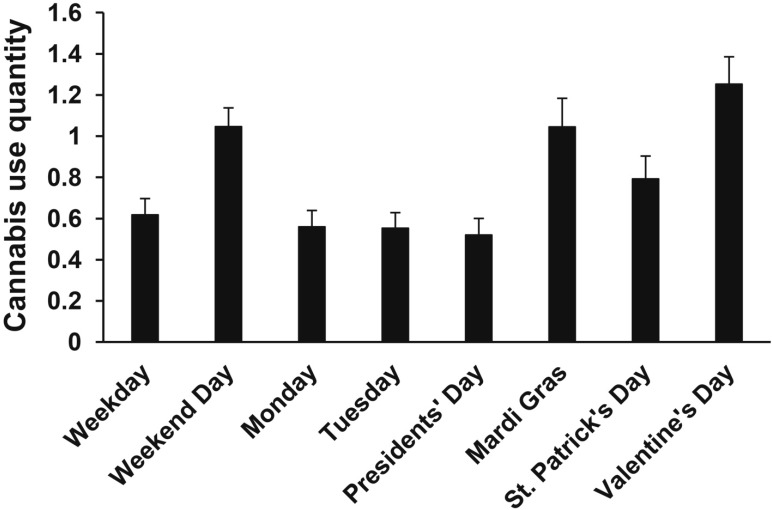

Given between-campus differences, campus was included as a covariate in these analyses. Figure 1 illustrates the mean cannabis use during specific days. Participants used more cannabis during typical weekends than typical weekdays, B = 0.58, SE = 0.08, p < .001.

Figure 1.

Mean cannabis use quantity per day

To confirm that Presidents’ Day was a non–cannabis-use holiday, use on Presidents’ Day was compared with a typical weekday, a typical weekend day, and a typical Monday. Participants reported using less cannabis on Presidents’ Day than they did on a typical weekday, B = 0.74, SE = 0.12, p < .001; a typical weekend day, B = 0.70, SE = 0.12, p < .001; and typical Monday, B = 0.77, SE = 0.07, p < .001.

Participants used more cannabis on MG than on a typical weekday, B = 0.61, SE = 0.144, p < .001; a typical Tuesday, B = 0.53, SE = 0.14, p < .001; and Presidents’ Day, B = 0.44, SE = 0.12, p < .001. Participants reported using slightly less cannabis on MG than on a typical weekend day, B = 0.66, SE = 0.12, p < .001. Among the 65 participants who used cannabis on MG, more cannabis was used during MG (M = 2.48 joints, SD = 2.48) than during a typical weekday (M = 1.23, SE = 1.24), B = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p = .038, and a typical weekend day (M = 1.75, SD = 1.27), B = 0.18, SE = 0.06, p = .003. MG cannabis users did not use significantly more cannabis on MG than they did during a typical Tuesday (M = 1.11, SD = 1.18), B = 0.09, SE = 0.07, p = .190, or Presidents’ Day (M = 1.06, SD = 1.27), B = 0.06, SE = 0.07, p = .379.

Participants used more cannabis during SPD than during a typical weekday, B = 0.64, SE = 0.10, p < .001; a typical weekend day, B = 0.63, SE = 0.09, p < .001; a typical Monday, B = 0.62, SE = 0.09, p < .001; and Presidents’ Day, B = 0.54, SE = 0.09, p < .001 (Figure 1). Among the 62 participants who used cannabis on SPD, more cannabis was used during SPD (M = 1.97, SD = 1.56) than during a typical weekday (M = 1.28, SD = 1.24), B = 0.29, SE = 0.06, p < .001; a typical weekend day (M = 1.76, SD = 1.31), B = 0.29, SE = 0.05, p < .001; a typical Monday (M = 1.18, SD = 1.23), B = 0.27, SE = 0.06, p < .001; and Presidents’ Day (M = 1.15, SD = 1.29), B = 0.20, SE = 0.06, p < .001.

One other holiday occurred during the period assessed—Valentine’s Day. Use on Valentine’s Day was compared to a typical weekday, a typical weekend day, and a typical Friday. Participants reported more cannabis use on Valentine’s Day than a typical weekday, B = 0.45, SE = 0.06, p < .001; a typical weekend day, B = 0.53, SE = 0.08, p < .001; a typical Friday (M = 1.20, SD = 1.24), B = 0.46, SE = 0.05, p < .001; and Presidents’ Day, B = 0.39, SE = 0.09, p < .001. Among the 84 participants who used cannabis on Valentine’s Day, their use on Valentine’s Day (M = 2.30, SD = 1.60) was greater than a typical weekday (M = 1.00, SD = 1.18), B = 0.21, SE = 0.05, p < .001; weekend day (M = 1.53, SD = 1.23), B = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p < .001; Friday (M = 1.75, SD = 1.31), B = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p < .001; and Presidents’ Day (M = 0.88, SD = 1.22), B = 0.14, SE = 0.05, p = .007.

Event-specific cannabis use by campus

Campus A students reported more cannabis use on MG (M = 1.30, SD = 1.87) than Campus B’s (M = 0.46, SD = 1.11), B = 1.04, SE = 0.33, p = .001. Contrary to expectation, Campus A also reported more cannabis use during SPD (M = 1.02, SD = 1.55) than Campus B (M = 0.26, SD = 0.61), B = 1.36, SE = 0.36, p < .001. Campus A reported significantly more cannabis use during MG than SPD, B = 0.44, SE = 0.07, p < .001. However, Campus B did not use significantly more during SPD than during MG, B = 0.17, SE = 0.55, p = .763.

As we predicted, among those students endorsing SPD use, Campus B’s (M = 7.00, SD = 7.09) reported more cannabis-related problems during SPD than Campus A’s (M = 2.66, SD = 3.11), B = 0.97, SE = 0.47, p = .040. Among those endorsing MG cannabis use, Campus A’s (M = 4.31, SD = 4.02) did not report more cannabis-related problems during MG than Campus B’s (M = 4.45, SD = 6.39), B = 0.03, SE = 0.37, p = .932. Campus A participants reported significantly more problems during MG than during SPD, B = 0.17, SE = 0.02, p < .001, and Campus B participants reported significantly more problems during SPD than during MG, B = 0.17, SE = 0.02, p < .001.

Discussion

The current findings extend prior work identifying Spring Break (Ragsdale et al., 2012) and musical festivals (Hesse et al., 2010) as events related to cannabis use in that cannabis use appears to vary as a function of specific event. Presidents’ Day was not associated with greater cannabis use (rather, it was associated with less use). Yet, cannabis use was greater during MG than during a typical weekday, a typical Tuesday, and Presidents’ Day. Among participants who used cannabis on MG, more cannabis was used during MG than during a typical weekend. Similarly, participants used more cannabis during SPD than during a typical weekday, a typical weekend day, a typical Monday, and Presidents’ Day. Interestingly, Valentine’s Day was also associated with more cannabis use. This is consistent with the finding that Valentine’s Day tends to be associated with more alcohol use (Neighbors et al., 2011). Given that cannabis tends to be used in social situations (Buckner et al., 2012), Valentine’s Day may be a high-risk cannabis use day because of the social nature of the holiday (e.g., romantic dates). Future work identifying the specific situations in which individuals are vulnerable to using cannabis on Valentine’s Day (e.g., during dates vs. during parties or other social gatherings) will be an important next step. In sum, MG, SPD, and Valentine’s Day appear to be high-risk holidays for cannabis use, and when students use cannabis on these days, use tends to be greater.

Campus differences in event-specific cannabis use were observed. Specifically, consistent with Campus A’s campus-wide traditions specific to MG, Campus A students reported greater cannabis use and use-related problems during MG than SPD. Consistent with Campus B’s campus-wide traditions specific to SPD, Campus B participants reported more cannabis-related problems during SPD than MG; despite not using more cannabis during SPD than Campus A, Campus B reported more cannabis-related problems during SPD than Campus A.

This is the first known study to examine event-specific cannabis-related problems. Consistent with the alcohol literature (Lewis et al., 2009), our data suggest that specific events may be high risk for cannabis-related impairment. This finding has important clinical implications, suggesting that therapists utilizing harm-reduction interventions may consider including skills to help students manage their use during high-risk holidays to minimize their experience of cannabis-related impairment.

There are limitations to this study that suggest the need for further research. First, relative to Campus A, Campus B had a smaller number of participants. Although this number is consistent with prior event-specific cannabis use research (Ragsdale et al., 2012), replication with larger, more diverse samples is necessary. Second, future work could benefit from multi-method (e.g., biological verification of cannabis use, prospective designs such as ecological momentary assessment) and multi-informant approaches. Third, the sample from Campus A was comprised of significantly more women than Campus B. Although men tend to use more cannabis (Stinson et al., 2006), Campus A participants reported more cannabis use during the time assessed. This may be because of more cannabis use by Campus A students during the MG season, which occurs from January 5 until MG day. Fourth, future work could benefit from testing whether April 20 (“4/20”) is also a high-risk cannabis use day.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tyler Renshaw, Ph.D., for consultation regarding statistical analyses.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grants 5R21DA029811-02 and 1R34DA031937-01A1. NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- Ashtari M., Cervellione K., Cottone J., Ardekani B. A., Sevy S., Kumra S. Diffusion abnormalities in adolescents and young adults with a history of heavy cannabis use. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R., Wechsler H., Johnston L. D. Correlates of college student marijuana use: Results of a US National Survey. Addiction. 1997;92:571–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner J. D., Crosby R. D., Silgado J., Wonderlich S. A., Schmidt N. B. Immediate antecedents of marijuana use: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2012;43:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner J. D., Ecker A. H., Cohen A. S. Mental health problems and interest in marijuana treatment among marijuana-using college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira K. M., Arria A. M., O’Grady K. E., Vincent K. B., Wish E. D. The occurrence of cannabis use disorders and other cannabis-related problems among first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman L. J., Chapman X P. Madison, WI: Unpublished test; 1983. Infrequency scale. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. S., Iglesias B., Minor K. S. The neurocognitive underpinnings of diminished expressivity in schizotypy: What the voice reveals. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;109:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca F. K., Darkes J., Greenbaum P. E., Goldman M. S. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett S. A., Lowry R., Cohen L. R., Dellinger A. M. Unsafe motor vehicle practices among substance-using college students. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 1999;31:667–673. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum P. E., Del Boca F. K., Darkes J., Wang C.-P., Goldman M. S. Variation in the drinking trajectories of freshmen college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:229–238. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M., Tutenges S., Schliewe S. The use of tobacco and cannabis at an international music festival. European Addiction Research. 2010;16:208–212. doi: 10.1159/000317250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer J. R., Walker D. D., Lee C. M., Palmer R. S., Mallett K. A., Fabiano P., Larimer M. E. Misperceptions of college student marijuana use: Implications for prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:277–281. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri E., Pope H. G., Jr., Yurgelun-Todd D., Gruber S. Attributes of heavy vs. occasional marijuana smokers in a college population. Biological Psychiatry. 1995;38:475–481. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00325-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. M., Maggs J. L., Rankin L. A. Spring break trips as a risk factor for heavy alcohol use among first-year college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:911–916. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz E. S., Patrick M. E., Morgan N. R., Bezemer D. H., Vasilenko S. A. State Patty’s day: College student drinking and local crime increased on a student-constructed holiday. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2012;27:323–350. doi: 10.1177/0743558411417866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. A., Lindgren K. P., Fossos N., Neighbors C., Oster-Aaland L. Examining the relationship between typical drinking behavior and 21st birthday drinking behavior among college students: Implications for event-specific prevention. Addiction. 2009;104:760–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. A., Jasper C. R., Hill D. R. Dressing in costume and the use of alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs by college students. Adolescence. 1993;28:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M., Lee X E., Wechsler H. Trends in marijuana and other illicit drug use among college students: Results from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. Journal of American College Health. 2003;52:17–24. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Atkins D. C., Lewis M. A., Lee C. M., Kaysen D., Mittmann A., Rodriguez L. M. Event-specific drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:702–707. doi: 10.1037/a0024051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Walters S. T., Lee C. M., Vader A. M., Vehige T., Szigethy T., DeJong W. Event-specific prevention: Addressing college student drinking during known windows of risk. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2667–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell T. J., Fals-Stewart W., Murphy M. Concurrent validity of a brief self-report drug use frequency measure. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:327–337. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulson R. L., Bradshaw S. D., Huff J. M., Peebles L. L., Hilton D. B. Risky sex behaviors among African American college students: The influence of alcohol, marijuana, and religiosity. North American Journal of Psychology. 2008;10:529–542. [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale K., Porter J. R., Zamboanga B. L., St. Lawrence J. S., Read-Wahidi R., White A. High-risk drinking among female college drinkers at two reporting intervals: Comparing spring break to the 30 days prior. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC. 2012;9:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. M., Sobell L. C., Sobell M. B., Leo G. I. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. C., Sobell M. B. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R. Z., Allen J. P., editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods (pp. 41–72) Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens R. S., Roffman R. A., Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson F. S., Ruan W. J., Pickering R., Grant B. F. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: Prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]