Abstract

Objective:

Although there is a clear association between early use of alcohol and short- and long-term adverse outcomes, it is unclear whether consumption of minor amounts of alcohol (less than a full drink) at a young age is prognostic of risk behaviors in later adolescence.

Method:

Data were taken from 561 students enrolled in an ongoing prospective web-based study on alcohol initiation and progression (55% female; 25% White non-Hispanic). Based on a combination of monthly and semiannual surveys, we coded whether participants sipped alcohol before sixth grade and examined associations between early sipping and alcohol consumption by fall of ninth grade, as well as other indices of problem behavior. Participants also reported on the context of the first sipping event.

Results:

The prevalence of sipping alcohol by fall of sixth grade was 29.5%. Most participants indicated that their first sip took place at their own home, and the primary source of alcohol was an adult, usually a parent. Youth who sipped alcohol by sixth grade had significantly greater odds of consuming a full drink, getting drunk, and drinking heavily by ninth grade than nonsippers. These associations held even when we controlled for temperamental, behavioral, and environmental factors that contribute to proneness for problem behavior, which suggests that sipping is not simply a marker of underlying risk.

Conclusions:

Our findings that early sipping is associated with elevated odds of risky behaviors at high school entry dispute the idea of sipping as a protective factor. Offering even just a sip of alcohol may undermine messages about the unacceptability of alcohol consumption for youth.

Although the minimum legal drinking age in the United States is 21 years, initiation of alcohol use typically occurs well before then (Grunbaum et al., 2004; Newes-Adeyi et al., 2005). Data from the 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey indicate that nationwide, one fifth of students in Grades 9–12 drank alcohol for the first time before age 13 years, roughly corresponding to the middle-school years (Eaton et al., 2012); similar rates were observed in 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data, with 16% reporting lifetime alcohol use by age 13 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). Even among very young adolescents ages 9–12 years (“tweens”), drinking prevalence is alarmingly high, with 10%, 16%, and 29% of fourth, fifth, and sixth graders, respectively, reporting having tried more than a sip of alcohol (Donovan et al., 2004). Early alcohol consumption is concerning, because alcohol use may have acute and prolonged neurobiological effects specific to the adolescent brain (Brown et al., 2000; Clark et al., 2008; Monti et al., 2005) and may interfere with the development of skills and behaviors necessary to negotiate the transition to adulthood (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). Considerable research has documented an association between early onset of alcohol use and a variety of short- and long-term adverse outcomes, including alcohol problems and use disorders (e.g., Dawson et al., 2007; Labouvie et al., 1997), other substance use (Labouvie et al., 1997; McGue et al., 2001), risky sexual behaviors (Stueve & O’Donnell, 2005), lower school achievement (McGue et al., 2001), unintentional injury (Hingson et al., 2000), and suicidality (Cho et al., 2007; Swahn et al., 2008).

Based on the risks associated with early drinking onset, some researchers have advocated for the development of programs targeted at increasing age at first drink, and delaying alcohol use onset is an objective for Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Although raising the minimum legal drinking age from age 18 to 21 has led to reductions in drinking and alcohol-related traffic fatalities (DeJong & Blanchette, 2014; Subbaraman & Kerr, 2013), evidence for the success of other programs targeted at delaying age at initiation is less compelling (Spoth et al., 2008). That there is no precise, shared understanding of what is meant by drinking onset makes direct comparisons across research studies challenging (Rolando et al., 2012).

First use of alcohol has been operationalized in several ways, including any use/trying of alcohol, even just a sip (e.g., Andrews et al., 2003; D’Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Geels et al., 2013; Gruber et al., 1996; Jackson et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 1997), any use without parental permission (e.g., Oxford et al., 2001; Sung et al., 2004; Trucco et al., 2011), use other than at a religious ceremony (Morean et al., 2012), alcohol use beyond a sip or a few sips/taste (e.g., Gunn & Smith, 2010; Guttmannova et al., 2011; Malone et al., 2012; Mason et al., 2011; Scholes-Balog et al., 2013; Warner & White, 2003), and “most or all” of a drink of alcohol (Jackson, 1997). These definitions either confound sip with full drink or imply that a few sips is a trivial amount that does not merit explicit investigation. Yet, even a few sips of alcohol can constitute a meaningful experience for naive drinkers who may experience ethanol’s physical and psychological effects after drinking as little as half a drink (Donovan, 2009). Whereas the prevalence of alcohol use disorders is close to zero among children and very young adolescents (Young et al., 2002), consumption of alcohol in this age group is not uncommon (Donovan et al., 2004; Jackson, 1997; Simons-Morton, 2004).

What remains unclear is whether consumption of minor amounts of alcohol (i.e., less than a full drink) at a young age is prognostic of risk behaviors in later adolescence. On the one hand, sipping/tasting alcohol may simply be an early manifestation of an underlying problem behavior syndrome, consistent with problem behavior theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). In rejection of social norms, some youth may engage in a cluster of risky behaviors (e.g., substance use, conduct problems, aggressiveness, and attention problems) and may have traits related to impulsivity (Kendler et al., 2003; Masse & Tremblay, 1997; McGue et al., 2001). Early exposure to alcohol may be an important trigger for problem behavior, changing the presentation of psychological dysregulation in childhood from an externalizing disorder to alcohol use during adolescence (Clark, 2004). Thus, sipping of alcohol during childhood and heavier consumption and substance use in later adolescence may both reflect a disposition for problem behavior.

In contrast, consumption of small amounts of alcohol may be relatively benign, for example, during times when trying alcohol is an opportunistic behavior associated with a specific event at which it is available. Sipping alcohol in the family context (e.g., at a family celebration) is believed by some to be protective by “inoculating” youth against future problem drinking (Jackson et al., 2012). Early experimentation with alcohol, however, might set a young adolescent on the path to later substance use and substance-related problems. Youth may perceive positive social reactions to consuming alcohol from peers or adults and may be more attentive to social norms about drinking. The literature consistently supports socialization processes at work in alcohol use initiation, with greater alcohol use among those with higher perceived and actual parental alcohol use and favorable parental attitudes toward use (e.g., Jackson 1997; Kosterman et al., 2000; Power et al., 2005; Spijkerman et al., 2007); this was recently demonstrated for sipping/tasting specifically (Donovan & Molina, 2014). Alcohol use in the household plays a key role in a child’s early development of alcohol-related schemas and attitudes toward drinking behavior (Zucker et al., 1995); drinking behavior is then maintained by ongoing expectations (Aas et al., 1998). In addition, once a child has tried alcohol, he or she may have greater awareness of ready access to alcohol in the household or elsewhere, and the child may find the effects of alcohol reinforcing (e.g., liking the taste of alcohol).

In the only study to explore the association between sipping and future risk behaviors, Donovan and Molina (2011) found that sipping was predictive of later alcohol use: Youth who reported sipping or tasting alcohol by age 10 were significantly more likely than nonsippers to initiate drinking (not just a sip or taste) by age 14 (33% vs. 21%, respectively). Thus, there is a need for continued research into whether sipping alcohol is prognostic of future problem behavior.

Overview

The goal of the present study was to examine whether sipping at a young age, before middle school, is significantly associated with problem behavior in later adolescence, by the first semester of high school. We extended work by Donovan and Molina (2011) by exploring additional problem behavior outcomes beyond early initiation of drinking: whether the participant got drunk, engaged in heavy episodic drinking, and engaged in (any) other substance use. To explore whether sipping is simply a marker of underlying risk for problem behavior, we also conducted analyses controlling for childhood externalizing behavior, impulsive personality traits, biological history of alcoholism, and alcohol use in the home environment. In addition, because little is known about the context of the first sipping experience, we descriptively report information about the beverage, how it was obtained, where the sipping took place, and whether the youth made further attempts to sip alcohol; this last might be construed as a subsequent milestone to initial sipping.

Method

Participants

The sample was from an ongoing 3-year prospective study on alcohol initiation and progression among early adolescents, a group who largely had not yet initiated alcohol use but who were expected to show developmental progression through increasingly severe alcohol involvement (see Jackson et al., 2014). Participants were 1,023 students in six Rhode Island middle schools (one urban, two rural, three suburban), with data collected in five cohorts enrolled 6 months apart. The sample comprised roughly equal numbers of sixth, seventh, and eighth graders (33%, 32%, and 35%, respectively) and was 52% female, 24% non-White (5% Black, 3% Asian, 2% American Indian, 8% mixed race, 6% other), and 12% Hispanic.

Procedure

Youth who were interested in participating and from whom we had written informed parental consent were invited to attend a 2-hour in-person group orientation session where project staff reviewed the expectations of the project, explained how the students would engage with the project over the project period, and collected contact information and assent from each student. Following the orientation, participants completed a 45-minute computerized baseline survey. At this time, participants were provided with a unique user ID, created their own personal password, and were given a project notebook to keep, which provided project contact information, frequently asked questions, incentive information, a standard drink visual, and fun facts and trivia.

Over the course of the study, participants were assessed over a 3-year period, with five semiannual (every 6 months) surveys over the first 2 years (alternating fall and spring) and a follow-up survey 1 year later. In addition, participants completed a shorter (10- to 15-minute) monthly survey for the first 2 years (24 surveys total). These assessments were conducted using web-based surveys. Participants were provided with multiple reminders (mailed card, email, text, phone calls) that alerted them that the survey was open, and access was granted with the ID and password provided at baseline. During the orientation sessions, emphasis was placed on finding a private location with Internet access to take the survey.

Because the goal of the present study was to predict alcohol and other substance use outcomes measured at the beginning of high school, it was necessary for the sample used here to have completed an assessment in the fall of ninth grade. Due to the design of the study, a subset of participants did not receive an assessment at this time (planned missingness) and were excluded here. Thus, the present study contains those participants (n = 561) who provided data for the ninth-grade fall assessment. These individuals did not differ from those not included on lifetime consumption of a full drink of alcohol at baseline but were less likely to be White (25% White vs. 32% non-White, p < .05) and were more likely to be female (55% female vs. 48% male, p < .05).

Measures

Demographics.

At baseline, gender, grade (sixth, seventh, or eighth), and race/ethnicity (recoded into White, non-Hispanic [reference group]; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; and other, non-Hispanic) were collected. Race/ethnicity was coded into White versus non-White for the present study.

Sipping by sixth grade.

Participants were asked at each monthly and semiannual assessment whether they had ever had a sip of alcohol, not including consumption as part of a religious service. If this item was endorsed, participants provided their age at the time of the sip. To determine if a student sipped before Grade 6, we used the minimum of all reported ages at first sip and subtracted it from age at the Fall Grade 9 assessment. If the difference was 3 years or more, the student was coded as sipping before sixth grade.

Alcohol and other substance use outcomes.

At each assessment, participants reported whether they had ever consumed a full drink of alcohol (not including consumption as part of a religious service), had ever been drunk, and had ever consumed three or more drinks per occasion (heavy episodic drinking [HED]). We used the maximum values across all monthly assessments and semiannual surveys that fell at or before the Fall Grade 9 assessment to form binary variables for each of the three drinking outcomes. Lifetime substance use was a binary variable reflecting whether the respondent endorsed ever smoking a full cigarette, using marijuana, or using other illicit drugs, taken from the semiannual survey that fell at the Fall Grade 9 assessment.

Potential confounds.

Externalizing was a mean across 35 items, taken from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1979). Parents were asked to report about their child’s behavior problems over the prior 6 months. Items were on a 3-point scale: not true (as far as you know) (0) to very true or often true (2).

To assess family (parental) history of alcoholism, parents were asked to indicate whether their child’s biological father or biological mother have/had a drinking problem. A binary variable was created in which one or more biological parents was scored as 1, and no biological parent was scored as 0.

Parental alcohol use was measured using the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) that assesses excessive alcohol consumption, drinking behavior, adverse psychological reactions, and alcohol-related problems. A mean was taken across items. Item responses varied across item but ranged from never/no (0) to four or more times a week/daily or almost daily/during the last year (4).

Personality.

Three domains of personality were taken from the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Lynam et al., 2006): sensation seeking, positive urgency, and negative urgency (six items each; α = .84, α = .85, and α = .85, respectively). Sensation seeking is interest in and tendency to pursue activities that are exciting and novel, negative urgency is the tendency to act rashly in response to high negative affect, and positive urgency is the tendency to act rashly in response to high positive affect (Cyders et al, 2007). Response options ranged from agree strongly (1) to disagree strongly (4). Scores were averaged across items in each subscale.

Context of the first sipping event.

The first time a respondent reported ever having (at least) a sip of alcohol, we obtained information about the context surrounding the first sip, including the participant’s age, type of alcoholic beverage, whether the participant continued to drink the beverage, to whom the beverage belonged, how the beverage was obtained, and where the sipping took place. In addition, participants indicated whether they remembered the first drink or whether somebody told them about it. Last, participants reported whether (since the first sip) their parents or other adults had offered a sip of their alcohol beverage and whether they had ever attempted to obtain alcohol from a parent/adult, either by asking for a sip or by intentionally taking sips without the adult’s knowledge.

Analytic plan

Logistic regression models were used to predict each outcome from whether the participant had sipped before sixth grade. To avoid confounding of sipping and consuming a full drink, we conservatively removed the portion (n = 23, 3.6%) of the sample that reported having had a full drink by the fall of sixth grade (or were missing on this variable); thus the final sample size for these analyses was n = 538.

Results

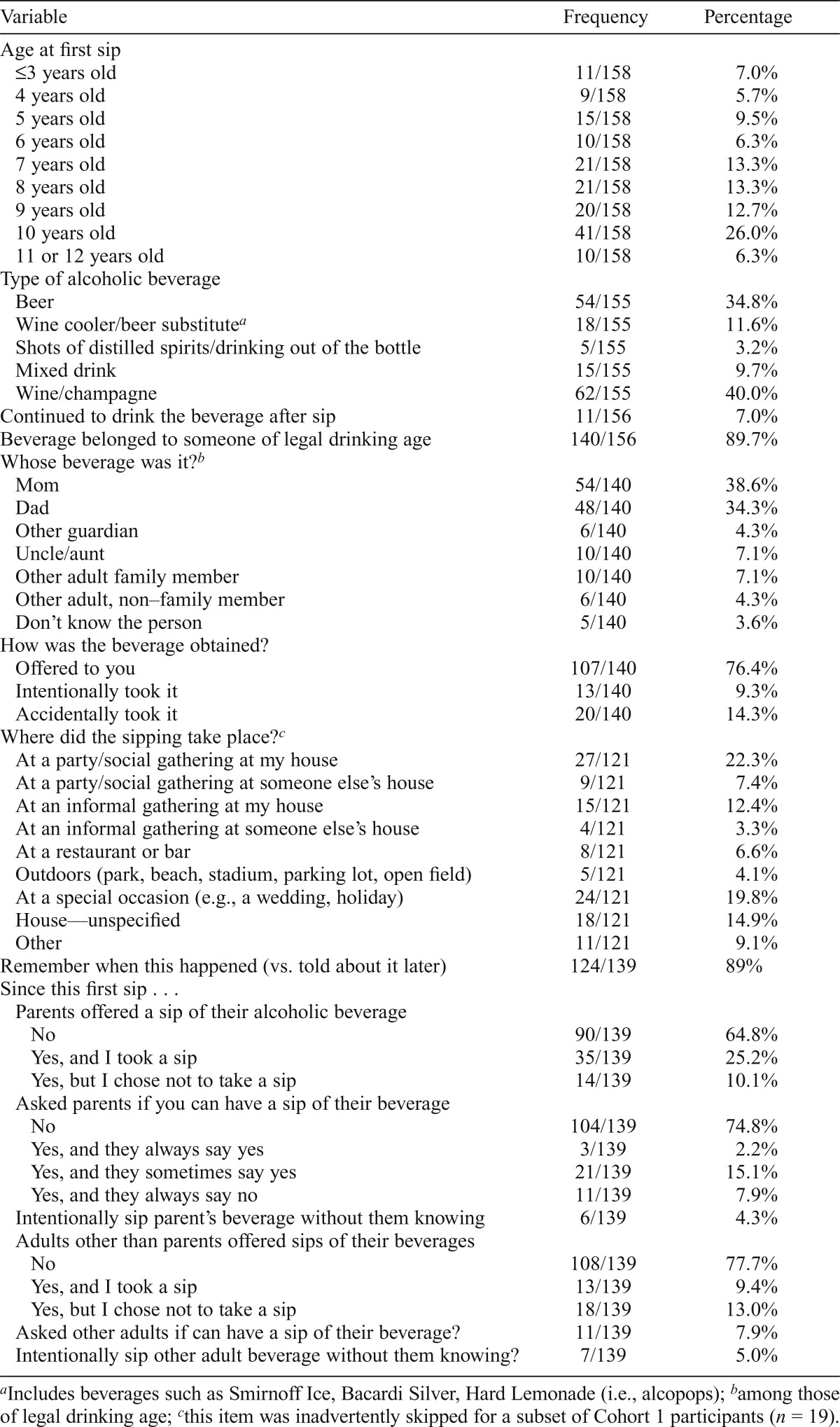

Context of first sip

The prevalence of having sipped alcohol by the fall of Grade 6 was 29.4% (158 of 538 respondents). The mean self-reported age at the respondent’s first sip was 7.61 years (SD = 2.63). The most commonly reported types of alcohol consumed at this first sipping occasion were wine (40.0%) and beer (34.8%), with very few (3%) having reported consuming distilled spirits (Table 1). Only 7% reported continuing to drink the beverage after the sip. Respondents reported that the primary source of alcohol was an adult, with nearly three quarters being the mother or father and only 8% of sources being a non–family member. Many participants indicated that their first sip took place at their own home, either at a party or social gathering or an informal event. Twenty percent reported that their first sip took place on a special occasion, such as a wedding or during a holiday. Nearly all participants recalled the experience, with only 11% being told about it by somebody else.

Table 1.

Context of first sip (n = 158)

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

| Age at first sip | ||

| ≤3 years old | 11/158 | 7.0% |

| 4 years old | 9/158 | 5.7% |

| 5 years old | 15/158 | 9.5% |

| 6 years old | 10/158 | 6.3% |

| 7 years old | 21/158 | 13.3% |

| 8 years old | 21/158 | 13.3% |

| 9 years old | 20/158 | 12.7% |

| 10 years old | 41/158 | 26.0% |

| 11 or 12 years old | 10/158 | 6.3% |

| Type of alcoholic beverage | ||

| Beer | 54/155 | 34.8% |

| Wine cooler/beer substitutea | 18/155 | 11.6% |

| Shots of distilled spirits/drinking out of the bottle | 5/155 | 3.2% |

| Mixed drink | 15/155 | 9.7% |

| Wine/champagne | 62/155 | 40.0% |

| Continued to drink the beverage after sip | 11/156 | 7.0% |

| Beverage belonged to someone of legal drinking age | 140/156 | 89.7% |

| Whose beverage was it?b | ||

| Mom | 54/140 | 38.6% |

| Dad | 48/140 | 34.3% |

| Other guardian | 6/140 | 4.3% |

| Uncle/aunt | 10/140 | 7.1% |

| Other adult family member | 10/140 | 7.1% |

| Other adult, non—family member | 6/140 | 4.3% |

| Don’t know the person | 5/140 | 3.6% |

| How was the beverage obtained? | ||

| Offered to you | 107/140 | 76.4% |

| Intentionally took it | 13/140 | 9.3% |

| Accidentally took it | 20/140 | 14.3% |

| Where did the sipping take place?c | ||

| At a party/social gathering at my house | 27/121 | 22.3% |

| At a party/social gathering at someone else’s house | 9/121 | 7.4% |

| At an informal gathering at my house | 15/121 | 12.4% |

| At an informal gathering at someone else’s house | 4/121 | 3.3% |

| At a restaurant or bar | 8/121 | 6.6% |

| Outdoors (park, beach, stadium, parking lot, open field) | 5/121 | 4.1% |

| At a special occasion (e.g., a wedding, holiday) | 24/121 | 19.8% |

| House—unspecified | 18/121 | 14.9% |

| Other | 11/121 | 9.1% |

| Remember when this happened (vs. told about it later) | 124/139 | 89% |

| Since this first sip … | ||

| Parents offered a sip of their alcoholic beverage | ||

| No | 90/139 | 64.8% |

| Yes, and I took a sip | 35/139 | 25.2% |

| Yes, but I chose not to take a sip | 14/139 | 10.1% |

| Asked parents if you can have a sip of their beverage | ||

| No | 104/139 | 74.8% |

| Yes, and they always say yes | 3/139 | 2.2% |

| Yes, and they sometimes say yes | 21/139 | 15.1% |

| Yes, and they always say no | 11/139 | 7.9% |

| Intentionally sip parent’s beverage without them knowing | 6/139 | 4.3% |

| Adults other than parents offered sips of their beverages | ||

| No | 108/139 | 77.7% |

| Yes, and I took a sip | 13/139 | 9.4% |

| Yes, but I chose not to take a sip | 18/139 | 13.0% |

| Asked other adults if can have a sip of their beverage? | 11/139 | 7.9% |

| Intentionally sip other adult beverage without them knowing? | 7/139 | 5.0% |

Includes beverages such as Smirnoff Ice, Bacardi Silver, Hard Lemonade (i.e., alcopops);

among those of legal drinking age;

this item was inadvertently skipped for a subset of Cohort 1 participants (n = 19).

Although very few youth (9%) purposely took their first sip on their own initiative, subsequent to the first sip, 25% went on to ask their parents if they could have a sip of their beverage; we note that this occurred during the elementary school years (i.e., before the fall Grade 6 assessment). There were no sex differences in any of the context variables in Table 1, with the exception that girls were less likely than boys to obtain the beverage from someone of legal drinking age (85% vs. 97%, p < . 05).

Prediction of risk behaviors by sipping

The prevalence of consuming a full drink by the fall of ninth grade was 11.5% (62/538), getting drunk was 3.9% (21/538), engaging in HED also was 3.9% (21/538), with 2.6% (14/538) reporting both. The prevalence of engaging in any substance use by ninth grade was 9.8% (52/532).

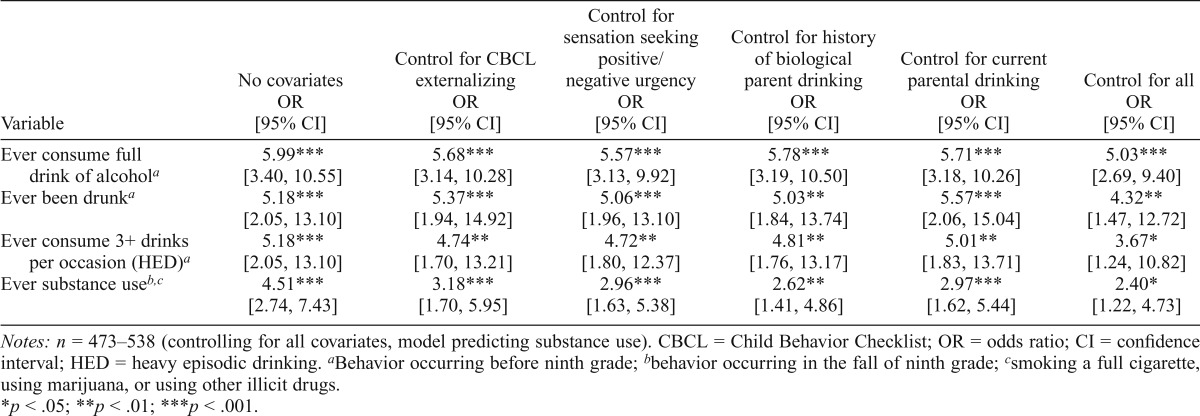

As shown in Table 2 (first data column), youth who sipped alcohol by fall of sixth grade had significantly greater odds of consuming a full drink by ninth grade; 26.0% of sippers consumed a full drink versus 5.5% of nonsippers. In addition, sippers had significantly greater odds of getting drunk and engaging in HED by ninth grade than nonsippers, 8.9% versus 1.8% for both outcomes, with 5.5% of the sippers reporting both getting drunk and HED versus 1.3% of nonsippers. Sippers also had significantly greater odds of reporting any substance use by ninth grade, with 17.3% reporting some substance use versus 6.6% of nonsippers.

Table 2.

Prediction of risk behaviors in ninth grade by whether a participant had sipped alcohol by sixth grade

| Variable | No covariates OR [95% CI] | Control for CBCL externalizing OR [95% CI] | Control for sensation seeking positive/negative urgency OR [95% CI] | Control for history of biological parent drinking OR [95% CI] | Control for current parental drinking OR [95% CI] | Control for all OR [95% CI] |

| Ever consume full drink of alcohola | 5 99*** [3.40, 10.55] | 5.68*** [3.14, 10.28] | 5.57*** [3.13, 9.92] | 5.78*** [3.19, 10.50] | 5.71*** [3.18, 10.26] | 5.03*** [2.69, 9.40] |

| Ever been drunka | 5.18*** [2.05, 13.10] | 5.37*** [1.94, 14.92] | 5.06*** [1.96, 13.10] | 5.03** [1.84, 13.74] | 5.57*** [2.06, 15.04] | 4.32** [1.47, 12.72] |

| Ever consume 3+ drinks per occasion (HED)a | 5.18*** [2.05, 13.10] | 4.74** [1.70, 13.21] | 4.72** [1.80, 12.37] | 4.81** [1.76, 13.17] | 5.01** [1.83, 13.71] | 3.67* [1.24, 10.82] |

| Ever substance useb,c | 4.51*** [2.74, 7.43] | 3.18*** [1.70, 5.95] | 2.96*** [1.63, 5.38] | 2.62** [1.41, 4.86] | 2.97*** [1.62, 5.44] | 2.40* [1.22, 4.73] |

Notes: n = 473–538 (controlling for all covariates, model predicting substance use). CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; HED = heavy episodic drinking.

Behavior occurring before ninth grade;

behavior occurring in the fall of ninth grade;

smoking a full cigarette, using marijuana, or using other illicit drugs.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

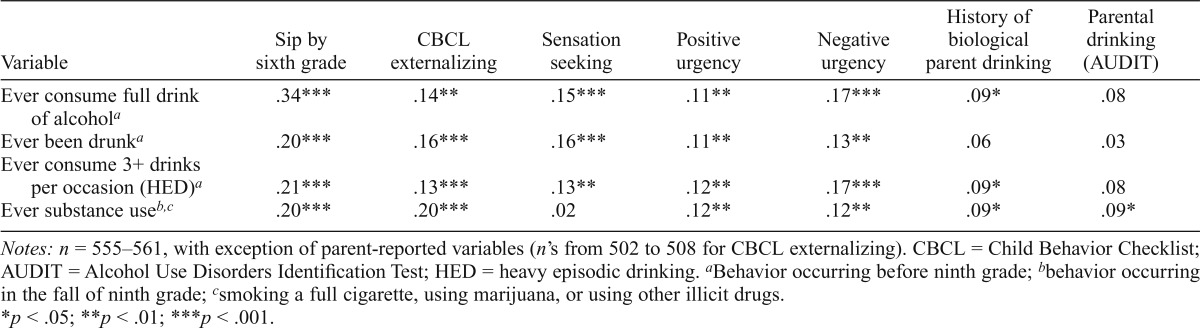

Next, we repeated our analyses, controlling for the following confounding variables: Child Behavior Checklist externalizing, impulsivity (sensation seeking, positive urgency, and negative urgency), history of alcoholism in the biological parent, and current parental drinking (AUDIT score). Table 3 presents correlations between sipping by sixth grade and these potential confounders and alcohol and other substance use by ninth grade. Importantly, early sipping has the highest correlation with outcome variables. When we controlled for the potential confounders, individually and together (in the final column; Table 2), associations between sipping and outcomes were robust: Although odds ratios were reduced in magnitude, for the most part, the associations were still large and highly significant, suggesting that sipping has a unique association with alcohol and other substance use over and above these indices of problem behavior.

Table 3.

Correlations between outcome variables, sipping by sixth grade, and potential confounders

| Variable | Sip by sixth grade | CBCL externalizing | Sensation seeking | Positive urgency | Negative urgency | History of biological parent drinking | Parental drinking (AUDIT) |

| Ever consume full drink of alcohola | .34*** | .14** | .15*** | .11** | .17*** | .09* | .08 |

| Ever been drunka | .20*** | .16*** | .16*** | .11** | .13** | .06 | .03 |

| Ever consume 3+ drinks per occasion (HED)a | .21*** | .13*** | .13** | .12** | .17*** | .09* | .08 |

| Ever substance useb,c | .20*** | .20*** | .02 | .12** | .12** | .09* | .09* |

Notes: n = 555–561, with exception of parent-reported variables (n’s from 502 to 508 for CBCL externalizing). CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; HED = heavy episodic drinking.

Behavior occurring before ninth grade;

behavior occurring in the fall of ninth grade;

smoking a full cigarette, using marijuana, or using other illicit drugs.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Ancillary analyses were conducted controlling for sex, race (White vs. non-White), and school (using five dummy-coded variables). Results were virtually identical with respect to both parameters and significance values. Last, across all models, there were no significant interactions with sex, ethnicity (White vs. non-White), or school.

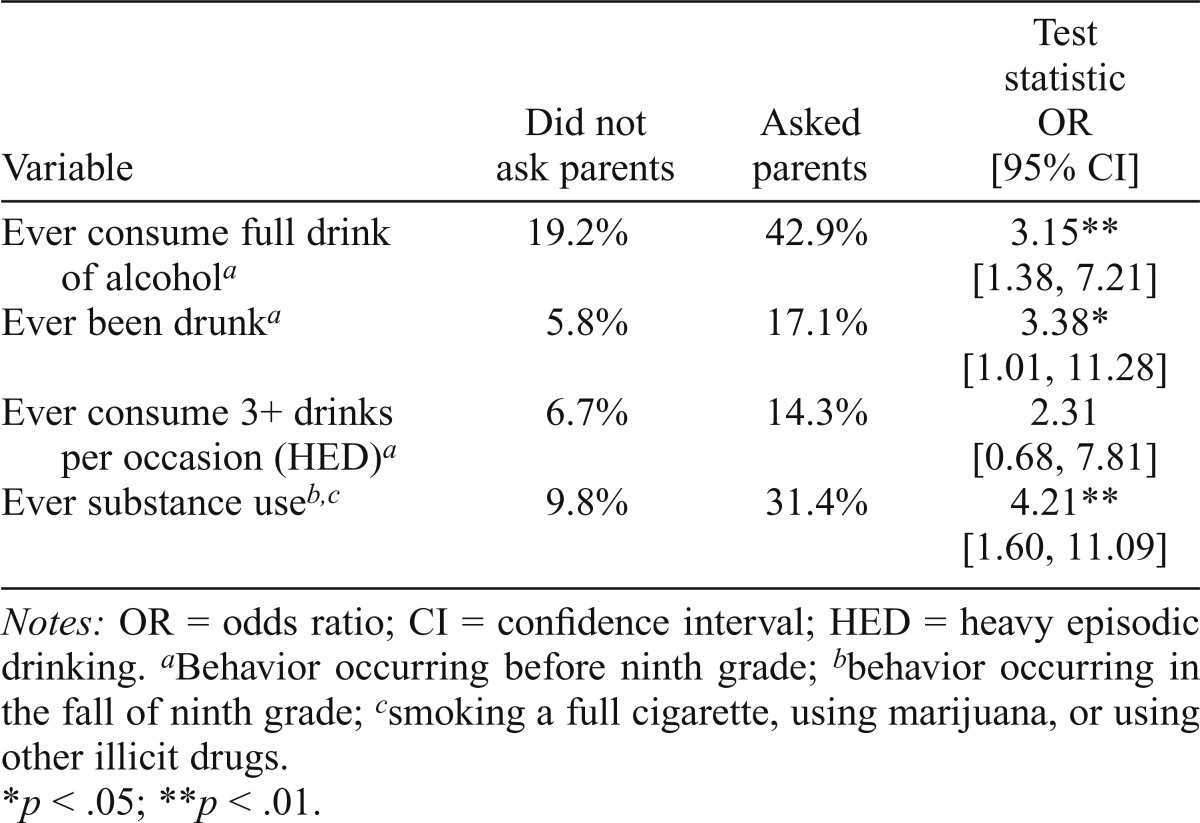

In addition, we conducted one last set of analyses exploring whether ninth-grade outcomes varied as a function of what could be construed as a subsequent milestone to sipping: asking parents for a sip of their alcoholic beverage. As Table 4 shows, odds of consuming a full drink and getting drunk by ninth grade were greater for those who made such a request. Further, nearly one third reported use of a substance other than alcohol, compared with fewer than 10% of those who did not make a request.

Table 4.

Prediction of risk behaviors as a function of whether the participant had proceeded to ask parents for a drink of their beverage among those who sipped (n = 137)

| Variable | Did not ask parents | Asked parents | Test statistic OR [95% CI] |

| Ever consume full drink of alcohola | 19.2% | 42.9% | 3.15** [1.38, 7.21] |

| Ever been drunka | 5.8% | 17.1% | 3.38* [1.01, 11.28] |

| Ever consume 3+ drinks per occasion (HED)a | 6.7% | 14.3% | 2.31 [0.68, 7.81] |

| Ever substance useb,c | 9.8% | 31.4% | 4.21** [1.60, 11.09] |

Notes: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; HED = heavy episodic drinking.

Behavior occurring before ninth grade;

behavior occurring in the fall of ninth grade;

smoking a full cigarette, using marijuana, or using other illicit drugs.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Discussion

The focus of this study was on a very early drinking milestone, the consumption of a sip of alcohol. Our study addressed a gap in the literature by examining whether sipping is prognostic of future problems, focusing on youth at the very earliest stage of alcohol involvement, a time when little drinking has occurred yet when personal norms accepting of sipping are beginning to emerge (Prins et al., 2011). Nearly one third of respondents reported having consumed, before middle school, at least a sip of alcohol that was not taken as part of a religious service, with a very young average age (Mage = 7.6 years) at first sip among these early sippers. In showing that early sipping is associated with elevated odds of risky behaviors at high school entry, our findings dispute the idea of sipping as a protective factor. We also describe the social setting in which early sipping occurs, moving beyond the preliminary evidence that sipping is likely to occur in the family context (Donovan & Molina, 2008) by investigating such aspects of the environment as drinking location, type of alcohol, and the source of alcohol.

Beer and wine were the most frequently endorsed beverage type for first sip(s) of alcohol. This stands in contrast to literature that indicates that distilled spirits are the most frequently consumed type of alcohol by adolescents, at least among high-schoolers (Cremeens et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2011), but is consistent with Donovan and Molina (2008), who also found wine to be the most commonly endorsed beverage type for sipping/tasting. Distilled spirits may not appeal or are not available to children and pre-adolescents. A subgroup of respondents endorsed drinking a beer substitute/wine cooler (alcopops), a relatively new product of the alcohol industry that is targeted to youth, particularly to young girls (Mart, 2011).

For this early milestone of sipping, nearly all respondents reported obtaining the alcohol from an adult over age 21, consistent with other studies on drinking sources (Foley et al., 2004; Jones-Webb et al., 1997; Wagenaar et al., 1996). Our study adds to the literature showing that parents are a frequently cited source of alcohol for pre-adolescents (either knowingly or not) (Gilligan et al., 2012; Ward & Snow, 2011). A small number of our participants intentionally took sips from adult beverages without the adult knowing (this was true for both first sip and subsequent drinks), with a similar portion sipping the beverage accidentally. This is consistent with work showing that very few elementary-schoolers who tried alcohol did so without their parents’ knowledge (Andrews et al., 2003). Donovan and Molina (2008) concluded that exposure to alcohol may be more opportunistic than deliberate, with youth living in households where parents drink and alcohol is available. We agree, although in contrast to our own findings; in their study, one third of mothers and more than half of fathers did not even know that their child had ever had a sip or a taste of alcohol, perhaps because the youth “snuck” a sip or was given a sip by another adult family member. But consistent with Donovan and Molina, our findings and those of Andrews et al. (2003) suggest that sipping alcohol is likely more strongly influenced by family behavior (i.e., parents offering the sip) and context than by youth “sneaking” early drinks. In addition, one in five respondents in our study reported that their first sip occurred at a special occasion such as a wedding or holiday, a percentage similar to that reported by Gilligan et al. (2014) in an Australian sample of youth age 12.

More than one third of respondents reported that their first experience sipping alcohol before middle school occurred at home (either a formal or informal gathering), consistent with prior literature showing that adolescents who start to drink at home/at a family gathering tend to have earlier ages at first use (Warner & White, 2003). Drinking outside the home is associated with riskier drinking in older adolescents, perhaps because of lack of social guardians and proscriptive norms regarding socially appropriate behavior (Forsyth & Barnard, 2000; Wells et al., 2005), or because adolescents do not feel comfortable drinking in the presence of their parents (Van Der Vorst et al., 2010). Thus, supervised drinking in the home may be associated with a lower risk relative to drinking outside the home; indeed, the degree to which childhood sipping/tasting of alcohol within a family context is protective has been a topic of recent debate.

A recent study by Jackson and colleagues (2012) concluded that a substantial proportion of parents believe that children can benefit from sipping drinks with alcohol, as it will remove the “forbidden fruit” appeal of alcohol and the taste will serve as a deterrent. Parents may rationalize that they are teaching their children to drink responsibly, thereby reducing risk of alcohol-related consequences (Livingston et al., 2010). However, permission to drink at home (Jackson et al., 1999; van der Vorst et al., 2010) and explicit provision of alcohol (Komro et al. 2007; McMorris et al., 2011; Shortt et al., 2007) are prospectively associated with greater levels of adolescent alcohol use, heavy use, drunkenness, and drinking intentions. Our results contribute to this literature by showing that sipping before middle school (compared with not sipping) was clearly associated with subsequent alcohol use, that youth who had sipped and then subsequently asked parents for a sip of their beverage showed elevated alcohol use, and that sipping at home was associated with other substance use beyond alcohol use. It may be that sipping and subsequently seeking alcohol from parents is a stepping stone to subsequent problem behavior.

Importantly, our findings suggest that early sipping of alcohol is not simply a marker for an underlying psychosocial disposition for problem behavior. Even accounting for temperamental, behavioral, and environmental factors that contribute to proneness for problem behavior, sipping was still strongly associated with subsequent alcohol and other substance use. Similarly, sipping was still predictive of more extreme alcohol outcomes even controlling for current parental alcohol use and history of alcoholism in biological parents, variables that might confer risk for substance use via environmental and genetic influences (Zucker, 2006). It is interesting to note that although genetic influences have been found to be lower for initiation than for heavy use or alcohol dependence (Hopfer et al., 2003), a study by Maes et al. (1999) showed that heritability estimates were very high when use without permission was specified. Present study findings better support the notion that early exposure to alcohol contributes to future drinking via altered norms or cognitions, a greater perception of alcohol’s availability, and/or increased risk because of the reinforcing properties of alcohol itself.

Our findings underscore the importance of advising parents to provide clear, consistent messages about the unacceptability of alcohol consumption for youth. Offering even a sip of alcohol may undermine such messages, particularly among younger children who tend to have more concrete thinking and may be unable to understand the difference between drinking a sip and drinking several drinks. In addition, parents should be encouraged to secure and monitor alcohol in the home (Friese et al., 2011), and given our reports of accidental consumption, parents should monitor their own beverages—children may intentionally or, as our data show, inadvertently take a sip. Of note, children who report having been asked by adults in the home to fetch or pour alcohol are shown to have greater odds of sipping alcohol (Jackson et al., 2013). Messages to parents about keeping their children from sipping alcohol may need to be provided via preventive intervention or community education, particularly because some parents report feeling pressured by other adults to allow their children to have sips of alcohol at social events (Gilligan & Kypri, 2012).

Limitations and future direction

Some study limitations must be noted. Our sample is drawn from a subset of schools in a single geographic region and thus is not representative of the United States. However, for the most part, our sample was reflective of the racial/ethnic distribution of each of the schools, as well as other sociodemographic characteristics. Although there was reasonable racial/ethnic heterogeneity in the sample, there were low numbers of Asian, American Indian, and mixed race/ethnicity participants, and the “other” category comprises these different groups, which typically have very different profiles of drinking. We failed to observe any interactions with sex or race/ethnicity, although we only contrasted Whites and non-Whites because of limited power in this selected sample. There is evidence that White youth are more likely to have obtained alcohol from their parents (Friese & Grube, 2008), and Latino youth are more likely than Whites or Blacks to receive alcohol from a nonrelative adult (Foley et al., 2004). This is a future area to explore.

Present study findings also may be biased toward younger users, given the age of our sample; findings may differ for youth who first gain experience with alcohol at an older age. The prominence of parents as a source of alcohol significantly decreases with children’s age (Hearst et al., 2007), with older adolescents more likely to use commercial sources (Forster et al., 1995; Harrison et al., 2000); thus, future work should look at the context of initial sipping at older ages. In addition, endorsement of sipping was based on self-reported use. However, studies suggest that self-report measures of alcohol consumption can be valid in youth (Donovan et al., 2004; Smith et al., 1995), particularly when using web-based data collection (Turner et al., 1998). Last, some participants reported very young ages at first sip (i.e., younger than 6 years). When we re-estimated our models excluding the 36 respondents who reported an age at first drink younger than age 6, however, both parameter values and significance were very similar to those identified with these respondents included (results available on request).

Despite these limitations, this study highlights the importance of focusing on this earliest drinking milestone. We hope that the present study findings will stimulate future research that characterizes early alcohol behavior and considers its importance with regard to subsequent problem behavior.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01 AA016838 (to Kristina M. Jackson).

References

- Aas H. N., Leigh B. C., Anderssen N., Jakobsen R. Two-year longitudinal study of alcohol expectancies and drinking among Norwegian adolescents. Addiction. 1998;93:373–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9333736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. M. The Child Behavior Profile: An empirically based system for assessing children’s behavioral problems and competencies. International Journal of Mental Health. 1979;7:24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. A., Tildesley E., Hops H., Duncan S. C., Severson H. H. Elementary school age children’s future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. A., Tapert S. F., Granholm E., Delis D. C. Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents: Effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H., Hallfors D. D., Iritani B. J. Early initiation of substance use and subsequent risk factors related to suicide among urban high school students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1628–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. B. The natural history of adolescent alcohol use disorders. Addiction, 99, Supplement. 2004;2:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. B., Thatcher D. L., Tapert S. F. Alcohol, psychological dysregulation, and adolescent brain development. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremeens J. L., Miller J. W., Nelson D. E., Brewer R. D. Assessment of source and type of alcohol consumed by high school students: Analyses from four states. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2009;3:204–210. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31818fcc2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T., Spillane N. S., Fischer S., Annus A. M., Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., McCarthy D. M. Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents’ substance use: The impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Li T.-K. Impact of age at first drink on stress-reactive drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W., Blanchette J. Case closed: Research evidence on the positive public health impact of the age 21 minimum legal drinking age in the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2014;17:108–115. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2014.s17.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E. Estimated blood alcohol concentrations for child and adolescent drinking and their implications for screening instruments. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e975–e981. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E., Leech S. L., Zucker R. A., Loveland-Cherry C. J., Jester J. M., Fitzgerald H. E., Looman W. S. Really underage drinkers: Alcohol use among elementary students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:341–349. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113922.77569.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E., Molina B. S. G. Children’s introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E., Molina B. S. G. Childhood risk factors for early-onset drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:741–751. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E., Molina B. S. G. Antecedent predictors of children’s initiation of sipping/tasting alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:2488–2495. doi: 10.1111/acer.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton D. K., Kann L., Kinchen S., Shanklin S., Flint K. H., Hawkins J., Wechsler H the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2011. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2012, June 8;61(4):1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley K. L., Altman D., Durant R. H., Wolfson M. Adults’ approval and adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:345.e17–345.e26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster J. L., Murray D. M., Wolfson M., Wagenaar A. C. Commercial availability of alcohol to young people: Results of alcohol purchase attempts. Preventive Medicine. 1995;24:342–347. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth A., Barnard M. Preferred drinking locations of Scottish adolescents. Health & Place. 2000;6:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese B., Grube J. Differences in drinking behavior and access to alcohol between Native American and white adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2008;38:273–284. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.3.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese B., Grube J. W., Seninger S., Paschall M. J., Moore R. S. Drinking behavior and sources of alcohol: Differences between Native American and White youths. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:53–60. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geels L. M., Vink J. M., Van Beijsterveldt C. E. M., Bartels M., Boomsma D. I. Developmental prediction model for early alcohol initiation in Dutch adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:59–70. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C., Kypri K. Parent attitudes, family dynamics and adolescent drinking: Qualitative study of the Australian Parenting Guidelines for Adolescent Alcohol Use. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:491–503. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C., Kypri K., Johnson N., Lynagh M., Love S. Parental supply of alcohol and adolescent risky drinking. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2012;31:754–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C., Toumbourou J. W., Kypri K., McElduff P. Factors associated with parental rules for adolescent alcohol use. Substance Use & Misuse. 2014;49:145–153. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.824471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E., DiClemente R. J., Anderson M. M., Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum J. A., Kann L., Kinchen S., Ross J., Hawkins J., Lowry R., Collins J. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2003 (Abridged) Journal of School Health. 2004;74:307–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn R. L., Smith G. T. Risk factors for elementary school drinking: Pubertal status, personality, and alcohol expectancies concurrently predict fifth grade alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:617–627. doi: 10.1037/a0020334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmannova K., Bailey J. A., Hill K. G., Lee J. O., Hawkins J. D., Woods M. L., Catalano R. F. Sensitive periods for adolescent alcohol use initiation: Predicting the lifetime occurrence and chronicity of alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:221–231. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P. A., Fulkerson J. A., Park E. The relative importance of social versus commercial sources in youth access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:39–48. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearst M. O., Fulkerson J. A., Maldonado-Molina M. M., Perry C. L., Komro K. A. Who needs liquor stores when parents will do? The importance of social sources of alcohol among young urban teens. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R. W., Heeren T., Jamanka A., Howland J. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1527–1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer C. J., Crowley T. J., Hewitt J. K. Review of twin and adoption studies of adolescent substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:710–719. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046848.56865.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. Initial and experimental stages of tobacco and alcohol use during late childhood: Relation to peer, parent, and personal risk factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C., Ennett S. T., Dickinson D. M., Bowling J. M. Letting children sip: Understanding why parents allow alcohol use by elementary school-aged children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166:1053–1057. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C., Ennett S. T., Dickinson D. M., Bowling J. M. Attributes that differentiate children who sip alcohol from abstinent peers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:1687–1695. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9870-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C., Henriksen L., Dickinson D. Alcohol-specific socialization, parenting behaviors and alcohol use by children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:362–367. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Roberts M. E., Colby S. M., Barnett N. P., Abar C. C., Merrill J. E. Willingness to drink as a function of peer offers and peer norms in early adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:404–414. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R., Jessor S. Problem behavior and psychosocial development. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. C., Greenland K. J., Webber L. S., Berenson G. S. Alcohol first use and attitudes among young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1997;6:359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R., Snowden L., Herd D., Short B., Hannan P. Alcohol-related problems among Black, Hispanic and White men: The contribution of neighborhood poverty. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:539–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. S., Jacobson K. C., Prescott C. A., Neale M. C. Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for use and abuse/dependence of cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants, and opiates in male twins. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:687–695. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro K. A., Maldonado-Molina M. M., Tobler A. L., Bonds J. R., Muller K. E. Effects of home access and availability of alcohol on young adolescents’ alcohol use. Addiction. 2007;102:1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R., Hawkins J. D., Guo J., Catalano R. F., Abbott R. D. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E., Bates M. E., Pandina R. J. Age of first use: Its reliability and predictive utility. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:638–643. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston J. A., Testa M., Hoffman J. H., Windle M. Can parents prevent heavy episodic drinking by allowing teens to drink at home? Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1105–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D. R., Smith G. T., Whiteside S. P., Cyders M. A. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior (Technical Report) West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University; 2006. Retrieved from http://www1.psych.purdue.edu/∼dlynam/uppspage.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Maes H. H., Woodard C. E., Murrelle L., Meyer J. M., Silberg J. L., Hewitt J. K., Eaves L. J. Tobacco, alcohol and drug use in eight- to sixteen-year-old twins: The Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:293–305. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone P. S., Northrup T. F., Masyn K. E., Lamis D. A., Lamont A. E. Initiation and persistence of alcohol use in United States Black, Hispanic, and White male and female youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mart S. M. Alcohol marketing in the 21st century: New methods, old problems. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46:889–892. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.570622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W. A., Toumbourou J. W., Herrenkohl T. I., Hemphill S. A., Catalano R. F., Patton G. C. Early age alcohol use and later alcohol problems in adolescents: Individual and peer mediators in a binational study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:625–633. doi: 10.1037/a0023320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masse L. C., Tremblay R. E. Behavior of boys in kindergarten and the onset of substance use during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:62–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130068014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M., Iacono W. G., Legrand L. N., Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. II. Familial risk and heritability. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris B. J., Catalano R. F., Kim M. J., Toumbourou J. W., Hemp-hill S. A. Influence of family factors and supervised alcohol use on adolescent alcohol use and harms: Similarities between youth in different alcohol policy contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:418–428. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P. M., Miranda R., Jr., Nixon K., Sher K. J., Swartzwelder H. S., Tapert S. F., Crews F. T. Adolescence: Booze, brains, and behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:207–220. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153551.11000.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean M. E., Corbin W. R., Fromme K. Age of first use and delay to first intoxication in relation to trajectories of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems during emerging adulthood. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:1991–1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newes-Adeyi G., Chen C. M., Williams G. D., Faden V. B. NIAAA Surveillance Report No. 74: Trends in Underage Drinking in the United States, 1991–2003. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005; 2005. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance74/Underage03.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford M. L., Harachi T. W., Catalano R. F., Abbott R. D. Preadolescent predictors of substance initiation: A test of both the direct and mediated effect of family social control factors on deviant peer associations and substance initiation. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:599–616. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power T. G., Stewart C. D., Hughes S. O., Arbona C. Predicting patterns of adolescent alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:74–81. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins J. C., Donovan J. E., Molina B. S. G. Parent–child divergence in the development of alcohol use norms from middle childhood into middle adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:438–443. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolando S., Beccaria F., Tigerstedt C., Törrönen J. First drink: What does it mean? The alcohol socialization process in different drinking cultures. Drugs: Education, Prevention, & Policy. 2012;19:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la Fuente J. R., Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes-Balog K. E., Hemphill S., Reid S., Patton G., Toumbourou J. Predicting early initiation of alcohol use: A prospective study of Australian children. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48:343–352. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.763141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Maggs J. L. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortt A. L., Hutchinson D. M., Chapman R., Toumbourou J. W. Family, school, peer and individual influences on early adolescent alcohol use: First-year impact of the Resilient Families programme. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2007;26:625–634. doi: 10.1080/09595230701613817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M. B., Naimi T. S., Cremeens J. L., Nelson D. E. Alcoholic beverage preferences and associated drinking patterns and risk behaviors among high school youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B. G. The protective effect of parental expectations against early adolescent smoking initiation. Health Education Research. 2004;19:561–569. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., McCarthy D. M., Goldman M. S. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R., van den Eijnden R. J. J. M., Overbeek G., Engels R. C. M. E. The impact of peer and parental norms and behavior on adolescent drinking: The role of drinker prototypes. Psychology & Health. 2007;22:7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R. L., Randall G. K., Trudeau L., Shin C., Redmond C. Substance use outcomes 5 1/2 years past baseline for partnership-based, family-school preventive interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A., O’Donnell L. N. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:887–893. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman M. S., Kerr W. C. State panel estimates of the effects of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol consumption for 1950 to 2002. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37, Supplement. 2013;1:E291–E296. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sung M., Erkanli A., Angold A., Costello E. J. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity on the development of substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn M. H., Bossarte R. M., Sullivent E. E., III Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:297–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco E. M., Colder C. R., Wieczorek W. F. Vulnerability to peer influence: A moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C. F., Ku L., Rogers S. M., Lindberg L. D., Pleck J. H., Sonenstein F. L. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Substance abuse. Washington, DC: Author; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=40. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst H., Engels R. C. M. E., Burk W. J. Do parents and best friends influence the normative increase in adolescents’ alcohol use at home and outside the home? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:105–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar A. C., Toomey T. L., Murray D. M., Short B. J., Wolfson M., Jones-Webb R. Sources of alcohol for underage drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:325–333. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B. M., Snow P. C. Factors affecting parental supply of alcohol to underage adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:338–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner L. A., White H. R. Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38:1983–2016. doi: 10.1081/ja-120025123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S., Graham K., Speechley M., Koval J. J. Drinking patterns, drinking contexts and alcohol-related aggression among late adolescent and young adult drinkers. Addiction. 2005;100:933–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.001121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S. E., Corley R. P., Stallings M. C., Rhee S. H., Crowley T. J., Hewitt J. K. Substance use, abuse and dependence in adolescence: Prevalence, symptom profiles and correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:309–322. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker R. A. Alcohol use and the alcohol use disorders: A developmental-biopsychosocial systems formulation covering the life course. In: Cicchetti D., Cohen D. J., editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 620–656. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker R. A., Kincaid S. B., Fitzgerald H. E., Bingham C. R. Alcohol schema acquisition in preschoolers: Differences between children of alcoholics and children of nonalcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:1011–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]