Abstract

Objective:

In this article, the authors estimate implementation costs for illicit drug screening and brief intervention (SBI) and identify a key source of variation in cost estimates noted in the alcohol SBI literature. This is the first study of the cost of SBI for drug use only.

Method:

Using primary data collected from a clinical trial of illicit drug SBI (n = 528) and a hybrid costing approach, we estimated a per-service implementation cost for screening and two models of brief intervention. A taxonomy of activities was first compiled, and then resources and prices were attached to estimate the per-activity cost. Two components of the implementation cost, direct service delivery and service support costs, were estimated separately.

Results:

Per-person cost estimates were $15.61 for screening, $38.94 for a brief negotiated interview, and $252.26 for an adaptation of motivational interviewing. (Amounts are in 2011 U.S. dollars.) Service support costs per patient are 5 to 7.5 times greater than direct service delivery costs per patient. Ongoing clinical supervision costs are the largest component of service support costs.

Conclusions:

Implementation cost estimates for illicit drug brief intervention vary greatly depending on the brief intervention method, and service support is the largest component of SBI costs. Screening and brief intervention cost estimates for drug use are similar to those published for alcohol SBI. Direct service delivery cost estimates are similar to costs at the low end of the distribution identified in the alcohol literature. The magnitude of service support costs may explain the larger cost estimates at the high end of the alcohol SBI cost distribution.

The social costs of illicit drug use exceed $193 billion per year in the United States (US DOJ 2011). The costs include the costs of drug use disorders as well as costs associated with the use of drugs by those without a disorder. Despite these enormous costs, only 10% of patients with substance use disorders receive treatment (Bouchery et al., 2011; Pating et al., 2012; Sacks et al., 2013), spurring public health efforts to identify unhealthy substance use in health care and other settings. Screening and brief intervention (SBI) is a public health approach designed to identify and address substance use and its associated consequences. SBI was originally developed to address unhealthy alcohol use, and alcohol SBI has a well-established evidence base in primary care settings (Jonas et al., 2012). SBI for unhealthy alcohol use has been given a B grade for effectiveness by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. SBI is also included in the essential health benefits package as a part of the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010 (Moyer, 2013).

The evidence base for illicit drug SBI (for illegal drugs and prescription drugs used without a prescription or more than prescribed) is less established. However, federal policy efforts, such as the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s (2013) strategy and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) (2014) implementation grants, promote SBI for both illicit drug and unhealthy alcohol use. Cost is a potential barrier to the widespread implementation of SBI. A recent review established how much it costs to provide alcohol SBI (Bray et al., 2012), but little information exists on the costs of illicit drug SBI. Given tight budgets across potential public and private funders, an understanding of the implementation costs of illicit drug SBI is needed to support its dissemination.

The primary focus of this study was to estimate implementation costs for an SBI program targeted at illicit drug use. To our knowledge, no current cost estimates for standalone drug SBI exist. To date, a single study has estimated the implementation costs of a drug SBI in conjunction with alcohol SBI (Bray et al., 2014). A second contribution of this study is to separate out two components of implementation costs explicitly: direct service delivery costs and service support costs. Direct service delivery costs are costs that vary directly with each additional patient given a screen or brief intervention and are primarily the labor costs associated with the provider. Service support costs (e.g., information technology [IT] and ongoing clinical supervision costs) are costs that are required to support direct service delivery, and they vary at a level higher than that of the patient direct service delivery costs (e.g., IT costs that are incurred at the program level).

We estimated costs from a randomized clinical trial: Assessing Screening Plus brief Intervention’s Resulting Efficacy (ASPIRE). The primary objective of ASPIRE was to determine the efficacy and effectiveness of two models of brief intervention for decreasing drug use and consequences in a primary care setting. The interventions were integrated with an existing SBI program, Massachusetts SBI Referral and Treatment (MASBIRT), at Boston Medical Center and originally funded by SAMHSA. For ASPIRE, MASBIRT health educators called health promotion advocates (HPAs) screened patients using the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). ASSIST is a validated instrument that can identify use and discriminate between abuse and dependence of several substances: tobacco, alcohol, and multiple types of illicit drugs (Humeniuk et al., 2008). The first four questions of the ASSIST were asked to determine whether the respondent used any illicit substance; conditional on screening positive for illicit drug use, the full ASSIST was administered to assess severity and risk. Patients who screened positive for at least one illicit drug were then randomized to one of three programs: a list of resources, a brief negotiated interview (BNI), and an adaptation of motivational interviewing (AMI). The resources-only patients received a brief list of drug treatment and help-line resources. MASBIRT HPAs delivered a structured brief intervention to patients in the BNI condition. AMIs were delivered by master’s-level counselors. The BNI was designed to be a 10- to 15-minute intervention, whereas the AMI was intended to be a more intensive, less structured intervention, lasting 30–45 minutes with an optional second session. The study sample consisted of 528 patients. A full description of the study, including details regarding the intervention, and training and supervision of counselors, is presented elsewhere (Saitz et al., 2014). As reported in Saitz et al. (2014), no significant effects of the intervention were found on the primary outcome of the trial.

Method

A primary purpose of the cost estimates is to inform health care providers about the per-patient costs of implementing drug SBI. Thus, the cost estimates reflect the provider perspective. This perspective excludes patient costs (e.g., transportation, work leave) and societal costs (e.g., cost of outpatient care associated with a referral to another provider).

A hybrid costing methodology was used to estimate direct service delivery and service support costs for SBI in the ASPIRE study. The hybrid approach to costing is described in Bray et al. (2012) and consists of activity-based costing and non–activity-based costing methods. Activity-based costing works from the bottom up and measures the cost per activity that is associated with an intervention and then aggregates the cost of all activities to estimate costs. Non–activity-based costing works from the top down and estimates the total cost of providing a service and divides by the total amount of the service provided to estimate an average cost per service. Costs that were exclusively for research activities were not included.

Although we prefer to use activity-based costing when appropriate data are available, a hybrid approach was necessary because several ASPIRE activities were inseparable from the existing MASBIRT clinical program, and several sources of data needed to estimate the service support costs pre-dated the ASPIRE study. For those activities for which we could not separate ASPIRE and MASBIRT costs, we assumed that the average costs for ASPIRE and MASBIRT were the same.

For activity-based costing, the first step is to develop a taxonomy of all service-related activities. This was conducted through meetings with ASPIRE investigators and research staff. The second step is to identify the resources required for each activity and a price for each resource. The measurement of resources was conducted through three methods: direct observation, administrative data, and interviews with research and MASBIRT clinical staff. For some activities, direct observation was infeasible, and administrative data (e.g., training records) and interviews with program staff (e.g., clinical supervisors describing how often they spoke with counselors) were used to provide resource use estimates. Prices were obtained from administrative records and publicly available data sources and are converted to 2011 U.S. dollars.

Direct service delivery activities included screening, BNI, and AMI, which required labor, material, and space resources to implement. Screening time estimates were obtained using research assistant/HPA time diaries from 40 unique screens. BNI and AMI sessions were recorded, and each recording had an electronic time stamp (n = 198 for BNI and n = 196 for AMI). For the AMI group, a weighted average of the time of the initial and second sessions was used because not all patients received a second session. The materials used for screening, BNI, and AMI were color copies of the screening instrument and informational handouts. All screenings and interventions were conducted in 10-foot × 10-foot examination rooms.

Wage estimates were taken directly from administrative data for HPAs ($20.25 per hour). It was common for research assistants to screen potential ASPIRE patients, but, because screens could not be separated between ASPIRE and MASBIRT, the HPA wage was used for all screens. Research assistants are potentially paid at an artificially low rate and are unlikely to be used in a nonresearch setting. The AMI counselors were graduate psychology students with master’s degrees who were paid at an artificially low rate for master’s-level counselors. Therefore, Boston–Cambridge–Quincy metropolitan statistical area wages for master’s-level counselors taken from the Bureau of Labor Statistics were used in place of administrative data ($34.34 per hour) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). For copying costs, the per-page color copy cost of $0.08 from the General Services Administration Schedule 51-500 was used because reliable administrative data were unavailable (General Services Administration, 2010). For the price of space, the estimated market cost per square foot per hour for Class A office space was obtained from a national real estate firm for the Boston metropolitan statistical area ($35.77) (Grubb & Ellis, 2010). All prices were converted to 2011 U.S. dollars.

Seven distinct activities were included in service support costs: IT system maintenance, clinic session start-up, replenishment staff training, booster training, staff meetings, and two versions of ongoing clinical supervision. With the exception of clinic session start-up, non–activity-based costing was used to estimate service support costs. A challenge in estimating service support costs is that the ASPIRE study used existing MASBIRT infrastructure for screening and the provision of BNI. Only the AMI component was unique to ASPIRE.

The MASBIRT program used an IT system that was separate from existing hospital IT systems to identify and track patients systematically. Results from the ASSIST and other assessments were captured in the MASBIRT IT system, as were records of other services provided. To reduce redundant screenings, HPAs used a daily “hot list” of patients who were targeted for screening because they had never been screened or had not been screened in the last 6 months. IT system maintenance costs comprised the cost of a single, full-time IT staff member and a software license that was renewed annually. Wages for the IT staff member and the annual price of the software license were obtained from program administrative records. The total cost was calculated by multiplying the ASPIRE study period of 2.75 years by the annual price of labor and materials. The denominator used to calculate the average cost was 29,069: the total number of screens, BNIs, and AMIs provided through ASPIRE and MASBIRT during the ASPIRE study period in this setting. IT system service support costs are applied to screening, BNI, and AMI.

Clinic session start-up time estimates involve the following tasks: locating a room to conduct SBI, printing out a hot list of potential patients to screen, and locating the appropriate clinical examination room. Research assistants/HPAs kept a time diary for each task across 46 unique clinic session start-ups. An average time per start-up was calculated across HPAs and was multiplied by HPA wage to get a per-activity cost. The program averaged 22 clinic session start-ups per week over 130 weeks, for a total of 2,860 clinic session start-ups. Clinic session start-up service support costs are applied to screening, BNI, and AMI.

Replenishment staff training included the cost of training replacement staff for those who left and needed to be replaced and trained. There were seven group retrainings, and each training required 120 hours of a clinical supervisor’s time. Individual counselors required 120 hours of training. We estimated that 30 staff members were retrained through the seven retrainings. The total staff time spent in replenishment training was adjusted by the proportion of all MASBIRT screens and BNIs that occurred during the ASPIRE. The wage for the clinical supervisor was $36.25 per hour and was obtained from program administrative records. For the total cost, the clinical supervisor’s wage was multiplied by the adjusted hours (99) and was added to the product of the HPA wage and the adjusted total hours for HPAs (513). We estimated average costs over the 28,873 ASPIRE/MASBIRT screens and BNIs during the ASPIRE. Replenishment staff training service support costs are applied to screening and BNI; no replenishment training was required for AMI counselors.

Booster trainings were provided to HPAs to refresh SBI skills. These trainings were conducted quarterly, and each training was 1 hour long. The MASBIRT program had an average monthly staff count of 15, and we estimated that each received 4 hours of booster training per year over 2.75 years, resulting in 165 total hours of staff time. The total cost of booster training was obtained by multiplying total hours by the HPA wage. To calculate the average cost, the 28,873 ASPIRE/MASBIRT screens and BNIs during ASPIRE were used as the denominator. Booster training service support costs are applied to screening and BNI. Given the small number of AMI counselors, booster training was wrapped into clinical supervision for AMI counselors (described below).

Staff meetings were conducted monthly, lasted for 3 hours on average, and involved 15 HPAs and a clinical supervisor. The 3 hours per meeting were multiplied by 33 months to obtain the total amount of time spent per staff member (99 hours). For the total cost, the clinical supervisor’s wage was multiplied by the 99 hours spent in staff meetings and was added to the product of the HPA wage, the 15 counselors, and the 99 hours per staff member. We estimated average costs over the 28,873 ASPIRE/MASBIRT screens and BNIs during the ASPIRE. Staff meeting service support costs are applied to screening and BNI. Again, the costs of staff meetings for AMI counselors were wrapped into clinical supervision.

BNI clinical supervision occurred on a monthly basis for 2 hours and involved each of the 15 HPAs and a single clinical supervisor. These costs are applied only to BNIs; screening did not require clinical supervision. The total hours spent in BNI clinical supervision was 64.5 hours, which reflects weighting by the ratio of ASPIRE BNIs to total MASBIRT BNIs. A total cost for this service support activity was estimated by multiplying the sum of the HPA and clinical supervisor wages by the 64.5 total hours. To calculate the average cost, the 198 ASPIRE BNIs were used as the denominator.

AMI clinical supervision was more intensive, occurring on a weekly basis for 1.5 hours per week for each of the three master’s-level counselors supervised by the clinical supervisor. These costs are applied only to AMIs. The total hours spent in AMI clinical supervision was 630 hours. The total cost for this service support activity was estimated by multiplying the sum of the master’s-level counselor and clinical supervisor wages by the 630 total hours. To calculate the average cost, the 196 AMIs were used as the denominator.

Service support costs per patient were calculated by aggregating the average cost per patient for the relevant service support activities. The average service support cost per patient for screening included the average cost per patient for IT system maintenance, clinic session start-up, replenishment staff training, booster training, and staff meetings. BNI’s service support cost per patient includes the same four activities as the screening service support cost plus BNI ongoing clinical supervision costs. The service support cost for AMI per patient included IT system maintenance, clinic session start-up, and AMI ongoing clinical supervision. Because the AMI did not use HPAs, the service support activities pertaining to HPA booster training and staff meetings were excluded from the AMI service support cost.

To obtain the cost per patient for screening, BNI, and AMI, the direct service delivery cost per patient and the service support cost per patient were added together.

Results

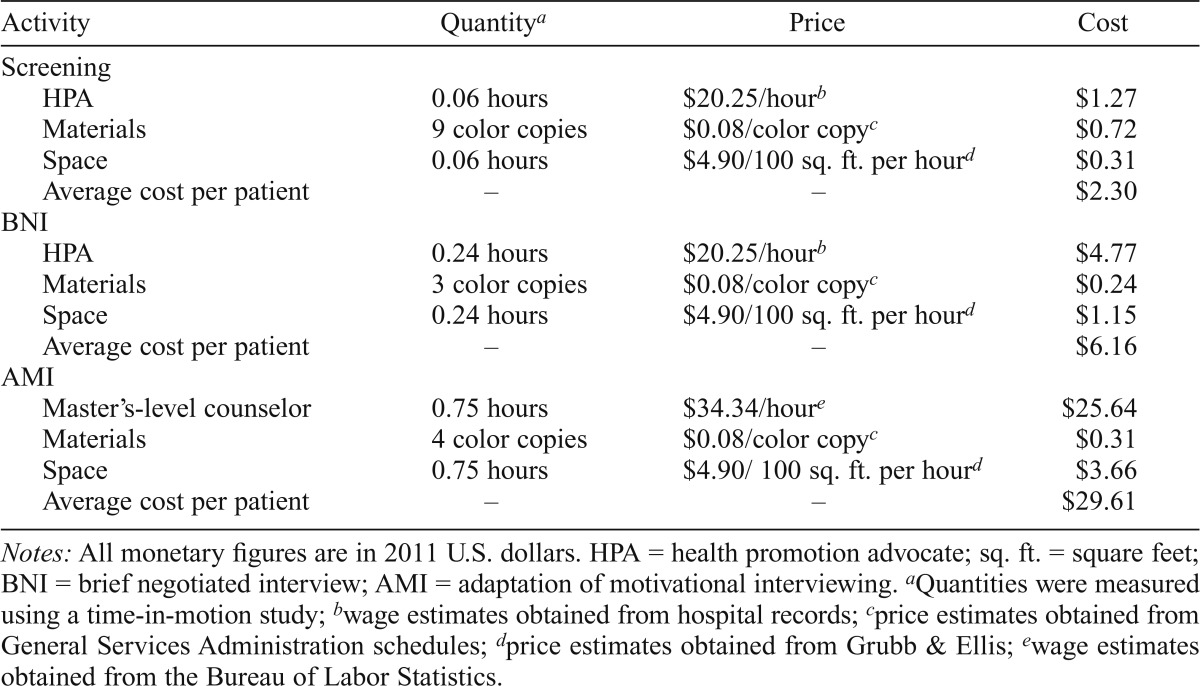

Table 1 presents detailed direct service delivery costs for screening, BNI, and AMI. The average cost per patient screened was $2.30, the average cost per patient receiving the BNI was $6.16, and the average cost per patient receiving the AMI was $29.61. The estimated time spent was 3.6 minutes for screening, 14.4 minutes for a BNI, and 45 minutes for an AMI. As expected, labor makes up the majority of the direct service delivery costs, accounting for approximately 55% of screening costs, 77% of BNI costs, and 87% of AMI costs. The master’s-level counselor that is required for AMI is more expensive than the HPA needed for BNI, and the AMI has a longer delivery time than the BNI (0.75 hours for AMI vs. 0.24 hours for BNI).

Table 1.

Detailed direct service delivery costs for drug screening and brief intervention

| Activity | Quantitya | Price | Cost |

| Screening | |||

| HPA | 0.06 hours | $20.25/hourb | $1.27 |

| Materials | 9 color copies | $0.08/color copyc | $0.72 |

| Space | 0.06 hours | $4.90/100 sq. ft. per hourd | $0.31 |

| Average cost per patient | – | – | $2.30 |

| BNI | |||

| HPA | 0.24 hours | $20.25/hourb | $4.77 |

| Materials | 3 color copies | $0.08/color copyc | $0.24 |

| Space | 0.24 hours | $4.90/100 sq. ft. per hourd | $1.15 |

| Average cost per patient | – | – | $6.16 |

| AMI | |||

| Master’s-level counselor | 0.75 hours | $34.34/houre | $25.64 |

| Materials | 4 color copies | $0.08/color copyc | $0.31 |

| Space | 0.75 hours | $4.90/100 sq. ft. per hourd | $3.66 |

| Average cost per patient | – | – | $29.61 |

Notes: All monetary figures are in 2011 U.S. dollars. HPA = health promotion advocate; sq. ft. = square feet; BNI = brief negotiated interview; AMI = adaptation of motivational interviewing.

Quantities were measured using a time-in-motion study;

wage estimates obtained from hospital records;

price estimates obtained from General Services Administration schedules;

price estimates obtained from Grubb & Ellis;

wage estimates obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

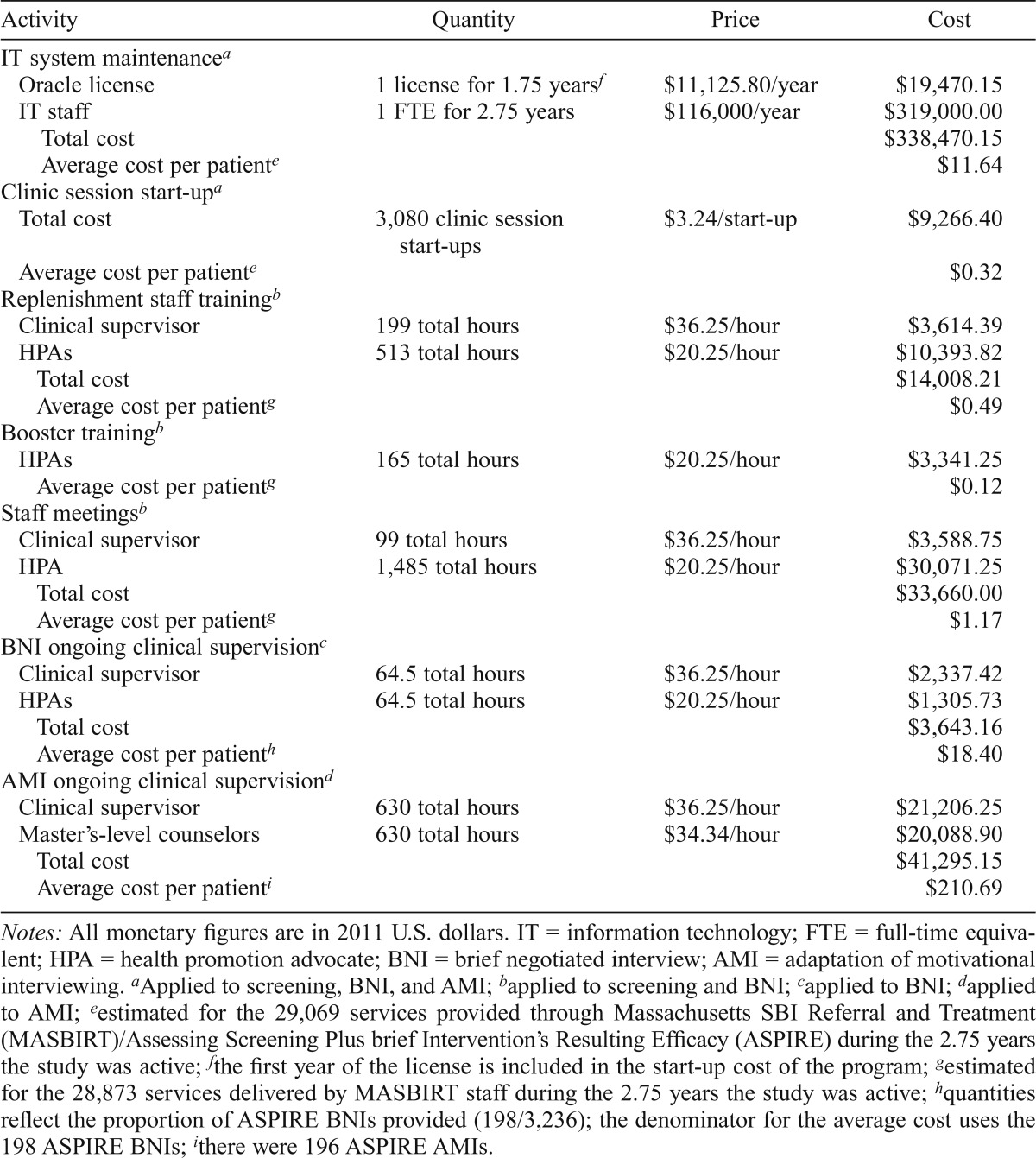

Table 2 reports detailed service support cost estimates. Booster training, clinic session start-up, replenishment staff training, and staff meetings were the least expensive service support activities, all costing $1.17 or less per patient. IT system maintenance and ongoing clinical supervision for the BNI were in the mid range, costing $11.64 and $18.40 per patient, respectively. Ongoing clinical supervision for the AMI was the most expensive at $210.69 per patient. Ongoing clinical supervision time for the AMI is almost 10 times greater than for BNI, which accounts for the substantially greater service support costs.

Table 2.

Detailed service support costs

| Activity | Quantity | Price | Cost |

| IT system maintenancea | |||

| Oracle license | 1 license for 1.75 yearsf | $11,125.80/year | $19,470.15 |

| IT staff | 1 FTE for 2.75 years | $116,000/year | $319,000.00 |

| Total cost | $338,470.15 | ||

| Average cost per patiente | $11.64 | ||

| Clinic session start-upa | |||

| Total cost | 3,080 clinic session start-ups | $3.24/start-up | $9,266.40 |

| Average cost per patiente | $0.32 | ||

| Replenishment staff trainingb | |||

| Clinical supervisor | 199 total hours | $36.25/hour | $3,614.39 |

| HPAs | 513 total hours | $20.25/hour | $10,393.82 |

| Total cost | $14,008.21 | ||

| Average cost per patientg | $0.49 | ||

| Booster trainingb | |||

| HPAs | 165 total hours | $20.25/hour | $3,341.25 |

| Average cost per patientg | $0.12 | ||

| Staff meetingsb | |||

| Clinical supervisor | 99 total hours | $36.25/hour | $3,588.75 |

| HPA | 1,485 total hours | $20.25/hour | $30,071.25 |

| Total cost | $33,660.00 | ||

| Average cost per patientg | $1.17 | ||

| BNI ongoing clinical supervisionc | |||

| Clinical supervisor | 64.5 total hours | $36.25/hour | $2,337.42 |

| HPAs | 64.5 total hours | $20.25/hour | $1,305.73 |

| Total cost | $3,643.16 | ||

| Average cost per patienth | $18.40 | ||

| AMI ongoing clinical supervisiond | |||

| Clinical supervisor | 630 total hours | $36.25/hour | $21,206.25 |

| Master’s-level counselors | 630 total hours | $34.34/hour | $20,088.90 |

| Total cost | $41,295.15 | ||

| Average cost per patienti | $210.69 |

Notes: All monetary figures are in 2011 U.S. dollars. IT = information technology; FTE = full-time equivalent; HPA = health promotion advocate; BNI = brief negotiated interview; AMI = adaptation of motivational interviewing.

Applied to screening, BNI, and AMI;

applied to screening and BNI;

applied to BNI;

applied to AMI;

estimated for the 29,069 services provided through Massachusetts SBI Referral and Treatment (MASBIRT)/Assessing Screening Plus brief Intervention’s Resulting Efficacy (ASPIRE) during the 2.75 years the study was active;

the first year of the license is included in the start-up cost of the program;

estimated for the 28,873 services delivered by MASBIRT staff during the 2.75 years the study was active;

quantities reflect the proportion of ASPIRE BNIs provided (198/3,236); the denominator for the average cost uses the 198 ASPIRE BNIs;

there were 196 ASPIRE AMIs.

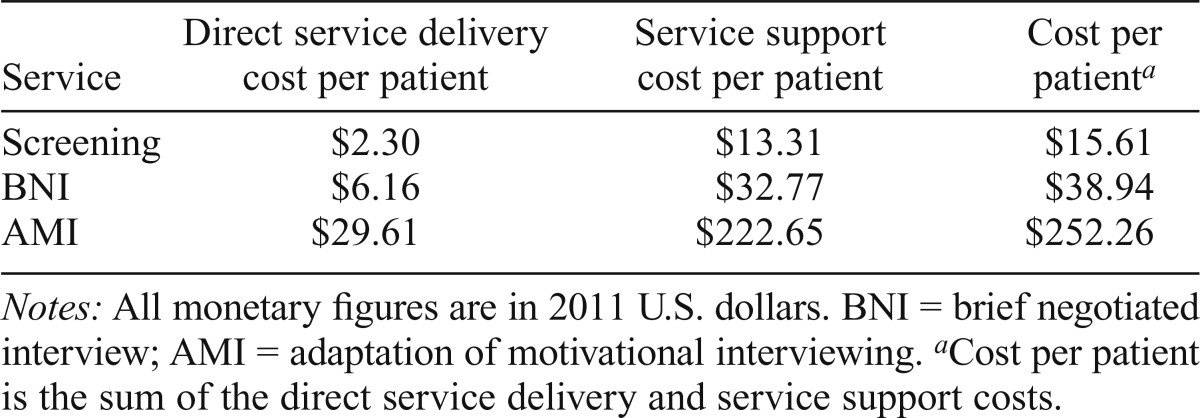

Table 3 presents the estimated cost per patient receiving screening, BNI, or AMI, which is the sum of the direct service delivery cost per patient and the service support cost per patient. For all activities, the service support costs are substantially larger than the direct service costs. For screening, IT system maintenance cost dominates the service support costs, accounting for $11.64 of the $13.31 service support costs. For BNI, ongoing clinical supervision and IT maintenance costs account for most of the $32.77 of the service support costs, and, for AMI, ongoing clinical supervision costs ($210.69) account for the vast majority of the service support costs ($222.65).

Table 3.

Average costs per service

| Service | Direct service delivery cost per patient | Service support cost per patient | Cost per patienta |

| Screening | $2.30 | $13.31 | $15.61 |

| BNI | $6.16 | $32.77 | $38.94 |

| AMI | $29.61 | $222.65 | $252.26 |

Notes: All monetary figures are in 2011 U.S. dollars. BNI = brief negotiated interview; AMI = adaptation of motivational interviewing.

Cost per patient is the sum of the direct service delivery and service support costs.

Discussion

This study estimated the cost of SBI for illicit drug use in a primary care setting. This article presents the per-patient implementation cost for screening, BNI, and AMI. As an extension, direct service delivery costs and service support costs are broken out for screening and for the two brief interventions: BNI and AMI. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the cost of SBI for drug use only.

Although all intervention cost studies must estimate the provider time (and the wage of the provider) required to perform the intervention, we paid particular attention to identifying the costs of services that are required to support and maintain the intervention. These costs include IT system maintenance costs, staff training for replacement staff, booster training, daily clinical session start-up costs, staff meetings, and ongoing clinical supervision.

Our estimated total costs per patient are $15.61 for screening—which is in the upper range of screening costs for alcohol screening as described in Bray et al. (2012)—and $38.94 for BNI, which is in the mid range of cost estimates for alcohol brief interventions in Bray et al. (2012). The estimated cost per patient for AMI, $252.26, is larger than any intervention cost estimate reported in Bray et al. (2012). As the BNI is similar to the typical brief intervention used in most alcohol SBI studies, we conclude that it is not more expensive to screen and perform a brief intervention for illicit drug use than it is for risky alcohol use.

We find that the direct service delivery cost estimates of screening and BNI are consistent with the costs at the low end of the distribution in Bray et al. (2012), and the direct service delivery cost estimate for AMI is in the mid range of costs. Our results clearly show that service support costs are an important part of SBI costs (especially ongoing clinical supervision costs), ranging from 5 to 7.5 times greater than direct service costs. To the extent that previous studies have ignored these costs, they have underestimated the true costs of providing SBI services. We speculate that much of the variation of alcohol SBI costs reflected in Bray et al. (2012) is explained by the authors’ differential inclusion of service support costs. Breaking out the different components of implementation costs sheds light on the wide distribution in Bray et al. (2012).

As noted, AMI costs substantially more than BNI when service support costs are taken into account—largely because of differences in ongoing supervision costs. In conjunction with the efficacy results that show no greater reduction in drug use for AMI versus BNI (Saitz et al., 2014), AMI is cost prohibitive and would not be considered to be an economically viable brief intervention option based on the ASPIRE efficacy results and the ASPIRE implementation model.

Estimates of service support costs may vary across sites, depending on potential differences in how the intervention is implemented. For example, in some programs, the incremental IT costs of adding SBI may be less than the $11.64 per patient estimated here because the nature and design of the IT system may accommodate IT system changes at a lower cost. Alternatively, some programs may choose to implement BNI and especially AMI with less clinical supervision than was done in the ASPIRE study. Although such a choice would certainly decrease brief intervention costs, reduced clinical supervision may affect the efficacy of the brief intervention.

The high service support costs for AMI may not be directly translatable beyond the current research study, but they should not be ignored or considered extremely unusual. ASPIRE staffing was maximized for patient coverage and fidelity and not necessarily for minimizing the average cost. Rather than having a single counselor covering all AMIs, multiple counselors were used for patient convenience. There is no guide on the appropriate level of supervision for AMI, and, although the protocol here may appear intensive, we felt that it was required to maintain fidelity. Efficiency gains through increased patient flow per counselor are possible.

The cost analysis has two primary limitations. First, the ASPIRE study relied on the patient flow and screening protocol from the MASBIRT program, which was originally funded by a SAMHSA grant. Although there are obvious gains from leveraging multiple sources of funding, our cost analysis faced the challenge of separating ASPIRE costs from MASBIRT costs. We attempted to separate these two programs, but some commingling of costs may still exist in our ASPIRE cost estimates.

Second, our cost study may not be generalizable to other sites. Although the direct service cost estimates are likely to be very similar across sites, we expect some variability associated with local wages and even greater variability across sites in how they implement their support services and the clinic size. Service support costs vary at the clinic level and depend, for example, on the number of HPAs employed and the patient flow. Increasing patient flow may require the hiring of additional HPAs. Thus, although the increased number of patients potentially lowers the average cost, the hiring of additional counselors may partially offset these potential economies of scale over a range of patients (see Cowell et al., in press, for a more comprehensive discussion of cost ramifications of staffing and patient flow).

Despite these limitations, our study provides guidance to policy makers on the costs of implementing SBI for drug use. By explicitly stating the key drivers for the direct service costs and the service support costs per patient, we provide policy makers with the ability to vary the resources and the price of those resources to estimate the cost of SBI for drug use in their own site with their specific implementation model.

The per-patient cost estimates can be used to estimate hypothetical program costs for the MASBIRT population during the 2.75 years of the ASPIRE study. Because MASBIRT did not provide AMIs, we did not estimate a program cost that includes AMI. Using patient flow from the full MASBIRT population during the ASPIRE study period, the program screened 25,637 patients and provided 3,236 BNIs during the study period. The screen positive rate was 12.6%, meaning that approximately eight patients were needed to be screened to deliver one BNI.

The total program costs over 2.75 years were $526,148, of which 76% were incurred through screening (including screening costs, we estimate a cost per BNI patient of $162.59). Although screening on a per-patient basis is much less expensive than other activities, it drives the program-level cost because all patients are screened. Even though BNI costs more than twice as much as the cost of a screen per patient, a much smaller patient population receives a BNI. Variation in the screen-positive rate may have a meaningful effect on program cost estimates. Holding all else constant, increasing the screen-positive rate to 20% increases the program costs to approximately $600,000 and reduces the share of screening costs to 66.7%. At a 30% screen-positive rate, there is close to a 50–50 split between screening and BNI costs. These calculations demonstrate the importance of considering both the cost per patient of drug SBI services and program-level parameters, such as the number of patients screened and the screen-positive rate.

In summary, this study estimates that the costs of implementing drug SBI are similar to those of alcohol SBI (Bray et al., 2012) and integrated alcohol/other drug SBI (Bray et al., 2014). Estimating different subcomponents of the implementation cost highlights that the key cost drivers are the time spent delivering brief intervention services and the service support costs; the key program-level cost drivers are the brief intervention model selected, the number screened, and the screen-positive rate. Future cost and cost-effectiveness studies of SBI should estimate costs for combined behavioral screening (alcohol, other drugs, and other health behaviors) and relate costs to measures of effectiveness.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA025068.

References

- Bouchery E. E., Harwood H. J., Sacks J. J., Simon C. J., Brewer R. D. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J. W., Zarkin G. A., Hinde J. M., Mills M. J. Costs of alcohol screening and brief intervention in medical settings: A review of the literature. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:911–919. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J. W., Mallonee E., Dowd W., Aldridge A., Cowell A. J., Vendetti J. Program- and service-level costs of seven screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment programs. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2014;5:63–73. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S62127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2010 Metropolitan and Non-metropolitan Area Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates: Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/oes/2010/may/oes_71650.htm#21-0000.

- Cowell A. J., Dowd W. N., Mills M. J., Bray J. W., Hinde J. M. Sustaining SBIRT in the wild: Simulating revenues and costs for substance abuse screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment programs. Addiction. in press doi: 10.1111/add.13650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Services Administration. GSA eLibrary: The Office, Imaging and Document Solution, Contractor Listing. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.gsaelibrary.gsa.gov/ElibMain/sinDetails.do?executeQuery=YES&scheduleNumber=36&flag=&filter=&specialItemNumber=51+100.

- Grubb & Ellis. Office market trends, Q4 2009, United States. 2010 Retrieved from www.centenn.com/o-09q4-national.pdf.

- Humeniuk R., Ali R., Babor T. F., Farrell M., Formigoni M. L., Jittiwutikarn J., Simon S. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103:1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas D. E., Garbutt J. C., Amick H. R., Brown J. M., Brownley K. A., Council C. L., Harris R. P. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157:645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer V. A. the Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159:210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. 2013 National Drug Control Strategy. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov//sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/ndcs_2013.pdf.

- Pating D. R., Miller M. M., Goplerud E., Martin J., Ziedonis D. M. New systems of care for substance use disorders: Treatment, finance, and technology under health care reform. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;35:327–356. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks J. J., Roeber J., Bouchery E. E., Gonzales K., Chaloupka F. J., Brewer R. D. State costs of excessive alcohol consumption, 2006. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45:474–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R., Palfai T. P. A., Cheng D. M., Alford D. P., Bernstein J. A., Lloyd-Travaglini C. A., Samet J. H. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: The ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312:502–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) 2014 Retrieved from http://beta.samhsa.gov/sbirt.

- United States Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center. The economic impact of illicit drug use on American society. 2011 Product No. 2011-Q0317-002. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44731/44731p.pdf.