Abstract

Objective:

Research consistently shows a positive association between racial discrimination and problematic alcohol use among African Americans, but little is known about the micro-processes linking this pernicious form of stress to drinking. One possibility is that the cumulative effects of discrimination increase individuals’ likelihood of negative-mood–related drinking. In the current study, we examined whether individual differences in lifetime perceived racial discrimination among African American college students moderate relations between daily negative moods and evening alcohol consumption in both social and nonsocial contexts.

Method:

Data came from an online daily diary study of 441 African Americans (58% female) enrolled at a historically black college/university. Lifetime discrimination was measured at baseline. For 30 days, students reported the number of drinks they consumed the night before both socially and nonsocially, as well as their daytime level of negative mood.

Results:

In support of the hypotheses, only men who reported higher (vs. lower) lifetime discrimination showed a positive association between daily negative mood and that evening’s level of nonsocial drinking. Contrary to expectation, women who reported higher (vs. lower) discrimination showed a negative association between daily negative mood and nonsocial drinking. Neither daily negative mood nor lifetime discrimination predicted level of social drinking.

Conclusions:

These findings provide further evidence that the cumulative impact of racial discrimination may produce a vulnerability to negative-mood–related drinking—but only for African American men. Importantly, these effects emerged only for nonsocial drinking, which may further explain the robust association between discrimination and problematic alcohol use.

In the past two decades, a compelling body of evidence has shown that individuals who experience more discrimination of any form exhibit worse mental and physical health than those who experience less discrimination (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Of particular interest, African Americans who report higher levels of perceived racial discrimination are more likely to exhibit drinking problems (Boynton et al., 2014; Gibbons et al., 2010; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2003). Although multiple theories have been proposed to explain why African Americans would respond to discrimination with problem drinking, rarely have micro-longitudinal data been used to explore the daily processes that might give rise to this maladaptive behavior. The current study asserts that racial discrimination, a pernicious form of chronic stress commonly experienced by African Americans of all ages (McLaughlin et al., 2010; Seaton et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2012), may engender drinking problems by conferring a vulnerability for negative-mood–related drinking. Alcohol consumption in response to negative moods, in turn, has been identified as an important predictor of alcohol problems independent of drinking levels (Cooper et al., 1995; Simons et al., 2005) and has been shown to have stronger associations with drinking problems among African Americans versus European Americans (Bradizza et al., 1999; Cooper et al., 1992). In the current study, we examined whether individual differences in lifetime perceived racial discrimination moderated relations between negative moods and alcohol consumption at the daily level of analysis. To test our hypotheses, we used data from a daily diary study (Gunthert & Wenze, 2012) of African American college students, a group that is diverse in terms of lifetime discrimination (Bynum et al., 2007; Swim et al., 2003) and may be at elevated vulnerability for drinking problems because of the high-risk nature of college alcohol use (Hingson et al., 2005; Rhodes et al., 2008).

One way in which racial discrimination may be linked to problematic alcohol use is through impaired self-regulation. According to Baumeister and colleagues’ strength model of self-regulation, individuals have a limited store of resources that are necessary to control one’s cognitions, emotions, and behaviors (Baumeister et al., 2007). Discriminatory interactions deplete individuals’ self-regulatory capacity, leaving them vulnerable to increased levels of negative mood and an inability to control their behavior (Richeson & Shelton, 2007). Although most prior research has focused on the syndrome of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological responses that occur during a specific episode of interracial contact, further evidence reveals that chronic exposure to discrimination impairs young African Americans’ levels of trait self-regulation (Gibbons et al., 2012). Chronically deficient self-regulation, in turn, may lead individuals to experience stronger negative moods in response to stress as well as increase their likelihood of engaging in negative-mood–related drinking when the opportunity arises.

Alternatively, chronic discrimination may produce deficiencies in African Americans’ coping abilities. Discrimination is profoundly stressful both psychologically and physiologically (Mays et al., 2007; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Pieterse et al., 2012), and racial discrimination has been found to have a more deleterious impact on alcohol use among African Americans who endorse drinking as a coping strategy versus African Americans who do not (Gerrard et al., 2012). Moreover, evidence suggests that drinking to cope may paradoxically increase negative mood as well as deplete self-regulatory resources (Armeli et al., 2014), a process that could trigger a maladaptive cycle in which coping skills are further deteriorated and alcohol use becomes a more primary means of coping. Although the goal of the current study was not to tease apart these alternative yet potentially complementary mechanisms, both provide a theoretical rationale for examining racial discrimination as a moderator of daily mood–drinking relations.

The deficits conferred by high levels of discrimination might be especially salient with regard to more maladaptive forms of alcohol use, such as nonsocial (i.e., without interacting with other people) or solitary drinking. Among college students, nonsocial drinking has been more strongly associated with both negative-mood–related drinking and drinking problems than has social drinking (Christiansen et al., 2002; Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013; Gonzalez et al., 2009; Mohr et al., 2005). Moreover, drinking in response to negative moods during adolescence has been shown to be associated with nonsocial alcohol use, which, in turn, predicts drinking problems approximately a decade later (Creswell et al., 2014). Chronic discrimination may be especially likely to produce higher levels of nonsocial (vs. social) drinking by shaping the way in which African Americans interact with the world. For example, individuals who report having experienced more (vs. less) lifetime discrimination are more likely to feel harassed, ignored, and treated unfairly during routine social interactions (Broudy et al., 2007). Negative interpersonal experiences, in turn, are also associated with nonsocial drinking (Mohr et al., 2005). Few studies, however, have examined nonsocial drinking among African Americans. Notably, evidence from a community sample showed that African American men were more likely to engage in nonsocial drinking than European American men and that doing so was more strongly associated with drinking quantity among the former group (Neff, 1997). It remains unknown, however, whether discrimination increases African Americans’ general propensity for nonsocial drinking, or specifically in response to negative moods.

Finally, we examined gender differences in the associations among racial discrimination, daily negative mood, and alcohol use. Both experimental and micro-longitudinal studies have demonstrated that men consume more alcohol in response to stress than do women (Armeli et al., 2000; Ayer et al., 2011; Nesic & Duka, 2006). Moreover, men appear less likely to experience the stress-dampening effects of alcohol (Ayer et al., 2011), which could lead to increased efforts to regulate mood via drinking (Armeli et al., 2014). Little of this work, however, has focused on African Americans, leaving open the question of whether gender differences generalize to this population. In addition, African American men perceive more racial discrimination than do African American women (Seaton et al., 2008), and men also appear more likely to engage in substance use as a response to this treatment (Boynton et al., 2014; Brodish et al., 2011; Brody et al., 2012). Together, these findings suggest that African American men will be more prone to negative-mood–related drinking than women, a difference that will be exacerbated among those who have experienced high levels of lifetime discrimination.

The current study is the first to examine whether individual differences in discrimination among African Americans moderate relations between daily negative mood and evening levels of drinking in social versus nonsocial contexts. Demonstrating that higher levels of discrimination are associated with negative-mood–related drinking could help shed light on the micro-processes linking discrimination to problematic alcohol use. To address these issues, we conducted a daily diary study of African American college students enrolled at a historically Black college/university (HBCU). Recruiting participants from an HBCU was ideal for maximizing power as well as external validity, as HBCU students are diverse with regard to academic performance and socioeconomic status (Kim & Conrad, 2006). Moreover, African American students at HBCUs report a wide range of alcohol-related problems, and drinking rates do not differ significantly between African American students at HBCUs versus those at other institutions (Meilman et al., 1995; Rhodes et al., 2008). We hypothesized that students who reported higher lifetime discrimination would show stronger associations between daily negative mood and that evening’s drinking levels than students reporting lower discrimination. Furthermore, we anticipated that these effects would be more pronounced for nonsocial versus social drinking. Finally, we hypothesized that men would show stronger relations between daily negative mood and alcohol use than would women, especially when they have experienced a high level of lifetime discrimination.

Method

Participants

All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at the study site and the corresponding authors’ institution. The baseline sample consisted of 741 undergraduates from an HBCU, of which 564 (76%) began the diary portion of the study. To be eligible, students must have consumed at least two drinks in the 30 days before prescreening. Students were excluded from analyses if they provided fewer than 14 of the 30 possible diary entries (n = 66), self-identified as other than Black/African American or African ancestry (n = 22), had ever sought treatment for alcohol issues (n = 5), or were missing scores for the discrimination measure (n = 30). These criteria resulted in a final sample for analysis of 441 students who completed 10,374 daily surveys (M = 23.5, SD = 4.6; 78% adherence rate). Participants were between 18 and 26 years old (M = 20.0, SD = 1.6), and the majority were female (58%). Comparing students in the initial cohort with those in the final sample revealed that noncompleters were more likely to be male, χ2(1) = 11.8, p < .001; no differences in attrition were found for age, year in school, lifetime discrimination, or baseline alcohol use.

Measures

Lifetime perceived racial discrimination was measured at baseline with the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). This scale has been well validated (Klonoff & Landrine, 1999) and has been associated previously with long-term changes in trait self-regulation (Gibbons et al., 2012). Students indicated how frequently they had encountered 17 different race-related discriminatory experiences in their lifetime (e.g., “How many times have you been treated unfairly by teachers or professors because you are Black?”) using the following scale: 1 (never), 2 (once in a while), 3 (sometimes), 4 (a lot), or 5 (all of the time). Items were averaged together (α = .93). In addition, for descriptive purposes, we calculated the number of events students reported having experienced in their lifetime (i.e., count of item reports > 1).

To control for the association between lifetime discrimination and prior drinking (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2010), we included baseline alcohol use as a covariate in our models. Specifically, participants reported the number of days in the past 30 days in which they consumed any alcohol, and in which they consumed four or more drinks (for women) or five or more drinks (for men) (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2004). To curtail skew in these measures, we recoded reports of 16 or more drinking days to a value of 16 (5.0% of sample) and reports of 11 or more heavy drinking days to a value of 11 (3.0% of sample). Participants also reported the typical number of drinks they consumed for each day of the week in the past 3 months, which were averaged together. These three measures were standardized and averaged (α = .85).

Evening alcohol use was measured by asking students each day how many alcoholic drinks they consumed the night before (i.e., between either yesterday’s survey or 6:00 p.m. and going to sleep). Separate items asked about social drinking (“with others/in a social setting”) and nonsocial drinking (“alone/not interacting with others”). Students responded using a 17-point scale from 0 to >15 drinks (recoded as 16). Daytime alcohol use (i.e., between waking and completing the daily survey) was measured in the same manner, but responses were combined and dichotomized because of the relative rarity of this behavior (0 = no daytime drinking, 1 = any daytime drinking). Students were reminded each day that a standard drink was defined as one 12-oz. beer or wine cooler, one 5-oz. glass of wine, or 1-oz. of distilled spirits.

Negative mood was measured by asking students to rate adjectives regarding how they felt from the time they awoke that day until taking the daily survey. Adjectives were chosen by the researchers based on the circumplex model of emotion (Larsen & Diener, 1992) and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Expanded (Watson et al., 1988), which has been used previously in a daily diary study of African American adults (Brondolo et al., 2008). Participants responded to items reflecting sadness (“sad,” “unhappy,” and “dejected”), anxiety (“anxious” and “nervous”), and anger (“angry” and “hostile”) using a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Ratings for each item were averaged together (α = .83; calculated across person-days).

Procedure

Undergraduate students were recruited at an HBCU from fall 2008 to fall 2011 via flyers, campus newspaper advertisements, emails, and face-to-face interactions. Interested students attended an introductory session, at which time they provided informed consent and were given login information for the secure website at which they could complete the baseline and daily diary surveys. Students participated in the diary study for 30 days and were compensated for both the baseline ($20) and daily surveys (up to $100 for perfect adherence, plus entry into a drawing with a 5% chance to win $100 for completing at least 25 surveys). Daily surveys could be accessed online between 2:30 p.m. (at which time an email reminder was sent to participants) and 7:00 p.m. This window approximated the time after students finished that day’s classes but before they were likely to begin evening activities. Students who missed the designated time for the daily survey could request to complete it up to noon the next day. In addition, to reduce the amount of missing outcome data, students who missed a survey were queried at their next login about their drinking behavior during the missed period. Given that drinking events are distinct, memorable, and occur at limited times of day (Gunthert & Wenze, 2012), it was expected that students could accurately report their drinking for up to 3 days earlier. Students provided 2,520 backfilled reports that included 761 evening social drinking episodes (24.1% of episodes) and 326 evening nonsocial drinking episodes (28.4% of episodes).

Analysis plan

To account for nesting of repeated-measures data within individuals, models were tested with generalized estimating equations (Hardin & Hilbe, 2003). These models are useful in that they include all available data from participants and handle nonnormal outcomes. Because both social and nonsocial number of drinks consumed were nonnormally distributed (i.e., positively skewed with only nonnegative integers as values), models were estimated with a negative binomial distribution and a log-link function (Coxe et al., 2009). Negative binomial models allow for overdispersion in the outcome as well as random, unexplained variation between participants. Exponentiation of slopes from these models can be interpreted as an index of effect size that describes a rate of change (Coxe et al., 2009). Specifically, for each 1-unit change in the predictor variable, the predicted count is multiplied by the exponentiated slope [exp(b)]. Positive associations, therefore, are indicated by an exp(b) > 1, and negative associations by an exp(b) < 1.

We conducted separate models predicting evening social and nonsocial drinking (reported for the previous evening on day t + 1) from that day’s level of negative mood (reported in the afternoon on day t). Individual-level predictors in these models included lifetime discrimination (grand-mean centered), baseline alcohol use, gender (-1 = male, 1 = female), age (centered at age 18), and year in school (dummy codes with first-year as the reference); additional daily predictors were weekend (0 = weeknight, 1 = Friday or Saturday night) and whether any daytime drinking had occurred (0 = no, 1 = yes). Daily mood was person-mean centered so that effects represented differences in drinking level based on deviations from each individual’s average mood over the study month (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Furthermore, the person-mean for daily negative mood was included as a predictor to allow us to separate within-person and between-person effects of daily mood on drinking (Curran & Bauer, 2011). Finally, we included a Daily Negative Mood × Discrimination × Gender interaction term (and all relevant two-way interactions) to test whether individuals who reported higher levels of discrimination showed stronger associations between daily negative mood and that evening’s level of drinking, and whether such relations differed between men and women. Interactions were probed using techniques recommended by Aiken and West (1991) to determine the significance of the simple slopes.

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for the study variables by gender. Although the average response for lifetime discrimination was approximately 2 on a 5-point scale (men: M = 2.09, SD = 0.74; women: M = 1.87, SD = 0.65), which corresponds to the label “once in a while,” students did report having experienced an average of approximately nine unique discriminatory events (men: M = 10.19, SD = 5.12; women: M = 8.69, SD = 5.05). Men reported more lifetime discrimination than did women, as well as heavier drinking behavior across all indicators (ps < .05) except number of heavy drinking days in the 30 days before baseline and average number of drinks per nonsocial drinking evening. Last, intraclass correlations were computed, which indicate the proportion of variance in each outcome explained by individual differences (Snijders & Bosker, 1999): social drinking = .35; nonsocial drinking = .64.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for primary study variables by gender

| Variable | Scale | Men (n = 186) M (SD) | Women (n = 255) M (SD) | p |

| Lifetime perceived racial discriminationa | 1–5b | 2.09 (0.74) | 1.87 (0.65) | .001 |

| Lifetime no. of discriminatory eventsa | 0–17 | 10.19 (5.12) | 8.69 (5.05) | .002 |

| No. of drinking days (past 30 days) | 0–30 | 7.13 (5.13) | 6.00 (4.54) | .015 |

| No. of heavy drinking days (past 30 days) | 0–30 | 3.40 (3.56) | 2.91 (3.46) | .142 |

| No. of drinks per day (past 3 months) | 0–10 | 1.41 (0.95) | 1.22 (0.93) | .034 |

| No. of social drinking evenings | 0–30 | 6.96 (4.78) | 5.75 (4.10) | .004 |

| No. of drinks per social drinking evening | 1–16 | 3.71 (1.94) | 3.10 (1.46) | <.001 |

| No. of nonsocial drinking evenings | 0–30 | 3.10 (4.12) | 1.69 (3.02) | <.001 |

| No. of drinks per nonsocial drinking evening | 1–16 | 2.67 (2.43) | 2.43 (1.98) | .300 |

Notes: No. = number.

Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996);

1 = never, 5 = all of the time.

Results from models predicting evening social drinking are displayed on the left side of Table 2. Students who were male, in their third year of college and beyond, and reported higher baseline alcohol use consumed significantly more social drinks over the study month. At the daily level, significantly more social drinking occurred on weekends and when daytime drinking had occurred. Most important, there were no significant associations between daily negative mood or lifetime discrimination and social drinking. Although a significant Daily Negative Mood × Gender interaction emerged, probing of the interaction revealed that the association between negative mood and social drinking was not significant for either gender.

Table 2.

Generalized estimating equations predicting evening number of social and nonsocial drinks

| Variable | Social drinks |

Nonsocial drinks |

||

| Exp(b) | [95% CI] | Exp(b) | [95% CI] | |

| Daily negative mooda | 0.99 | [0.86, 1.10] | 1.01 | [0.84, 1.22] |

| Genderb | 0.87*** | [0.80, 0.94] | 0.82** | [0.70, 0.95] |

| Lifetime discriminationc | 1.10 | [0.99, 1.23] | 0.98 | [0.79, 1.22] |

| Baseline alcohol use | 1.67*** | [1.53, 1.83] | 1.71*** | [1.46, 2.00] |

| Aged | 0.95 | [0.87, 1.02] | 1.16† | [0.98, 1.36] |

| 2nd year vs. 1st year | 0.95 | [0.75, 1.22] | 1.17 | [0.76, 1.79] |

| 3rd year vs. 1st year | 1.34* | [1.00, 1.80] | 0.80 | [0.42, 1.53] |

| 4th/5th year vs. 1st year | 1.63** | [1.20, 2.20] | 0.55† | [0.28, 1.08] |

| Aggregate negative mood | 1.18 | [0.93, 1.45] | 2.50*** | [1.85, 3.38] |

| Weekende | 5.98*** | [5.23, 6.83] | 2.82*** | [2.27, 3.51] |

| Daytime alcohol usef | 3.28*** | [2.57, 4.18] | 4.84*** | [3.46, 6.76] |

| Daily Negative Mood × Gender | 0.88* | [0.79, 0.98] | 0.91 | [0.76, 0.92] |

| Daily Negative Mood × Discrimination | 1.02 | [0.89, 1.17] | 0.96 | [0.76, 1.22] |

| Gender × Discrimination | 1.02 | [0.92, 1.13] | 1.12 | [0.92, 1.37] |

| Daily Negative Mood × Gender × Discrimination | 0.95 | [0.83, 1.09] | 0.67*** | [0.53, 0.85] |

Notes: Exp(b) = exponentiated slope; CI = confidence interval.

Person-mean centered;

male = -1, female = 1;

grand-mean centered;

centered at 18;

weekday = 0, weekend = 1;

no drinking = 0, drinking = 1.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

The pattern of results for nonsocial drinking, shown on the right side of Table 2, supported the hypotheses. Aggregate daily negative mood was significantly associated with evening nonsocial drinking, with a 1-unit increase in negative mood associated with a 150% increase in nonsocial drinks consumed over the study month. In addition, more nonsocial drinking occurred among men and students who reported higher baseline alcohol use, as well as on weekends and when daytime drinking had occurred. Again, neither daily negative mood nor discrimination was associated with evening nonsocial drinking, but these effects were qualified by a significant Daily Negative Mood × Lifetime Discrimination × Gender interaction.

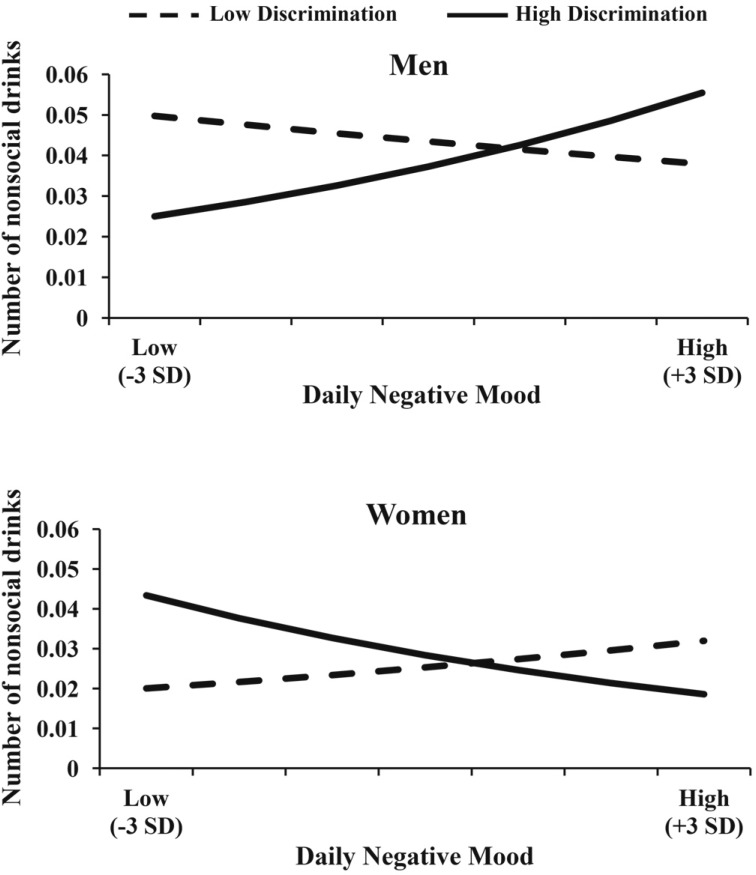

Probing of the interaction revealed that the Daily Negative Mood × Discrimination interactions were significant for both men, exp(b) = 1.43, p < .05, and women, exp(b) = 0.64, p = .01, although the pattern for women was in the opposite direction as hypothesized. Figure 1 displays these interactions separately for men and women, with the outcome scales converted into number of drinks consumed (i.e., exponentiated predicted values). Men who reported higher levels of lifetime discrimination consumed significantly more drinks in nonsocial settings on days when they experienced elevated levels of negative mood, exp(b) = 1.39, p < .03, whereas men who reported lower levels of discrimination showed no association, exp(b) = 0.92, p = .63. Contrary to expectation, women who reported higher levels of discrimination consumed significantly fewer nonsocial drinks on days when they experienced elevated negative mood, exp(b) = 0.71, p = .04. Women with lower levels of discrimination, however, drank more in nonsocial settings when they experienced a more negative mood, exp(b) = 1.70, p = .007.

Figure 1.

Daily Negative Mood × Lifetime Perceived Racial Discrimination × Gender interaction predicting evening number of nonsocial drinks consumed. High and low values for lifetime perceived racial discrimination represent +/- 1 SD from the mean, respectively. High and low values for daily negative mood represent +/- 3 SD from the mean, respectively. Predicted values were exponentiated to convert the outcome scale to number of nonsocial drinks consumed.

Discussion

Numerous studies have demonstrated associations between racial discrimination and problematic drinking among African Americans (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2010), but few have used micro-longitudinal data to examine daily processes that might explain this link. This is the first study to test whether lifetime perceived racial discrimination moderates relations between daily negative mood and evening levels of social and nonsocial drinking. As hypothesized, male African American college students who reported higher (vs. lower) levels of lifetime discrimination showed evidence of negative-mood–related drinking, but only in nonsocial contexts. Female African American students who reported higher discrimination, however, showed inverse associations between evening nonsocial drinking and daily negative mood, failing to support the hypotheses. Moreover, discrimination had no significant main or interactive effects related to levels of social drinking.

These findings are consistent with evidence that African American men are more responsive to discrimination in terms of substance use than are women (Boynton et al., 2014; Brodish et al., 2011; Brody et al., 2012) and that men, in general, are more likely to drink in response to stress (Armeli et al., 2000; Ayer et al., 2011; Nesic & Duka, 2006). These results also support previous theorizing regarding the impact of racial discrimination on alcohol use—that these chronic, stressful experiences lead to a greater likelihood of drinking in response to negative emotions, which may be due in part to long-term changes in self-regulation or coping capacity (Gerrard et al., 2012; Gibbons et al., 2012; Hatzenbueler et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2003). Moreover, the results for men suggest that the association between discrimination and problem drinking may be attributable to consuming more alcohol when not interacting with others, consistent with previously observed links between nonsocial drinking and drinking problems (e.g., Gonzalez & Skewes, 2013). Importantly, the observed relations between discrimination and negative-mood–related drinking cannot be attributed to previous alcohol use, which was controlled for in our models.

Women, however, showed the opposite pattern in which discrimination was inversely related to the within-person association between daily negative mood and that evening’s level of nonsocial drinking. Although this pattern was not predicted and requires replication, prior evidence indicates that African American women tend to be socialized with better coping responses to discrimination, such as seeking social support (Scott, 2004; Swim et al., 2003). In this case, women exposed to more lifetime discrimination may actually have been better trained to cope with negative mood than their female counterparts with less exposure who did show evidence of negative-mood–related drinking. However, women who reported higher levels of discrimination consumed more alcohol at lower levels of negative mood, a difference that may also be driven by the chronic-stress model described earlier, but in a more adaptive fashion (e.g., greater drinking for social or enhancement reasons when negative affect is low). These results leave many questions regarding relations between discrimination and alcohol use among African American women that require further study.

These findings speak to the potential importance of interventions, especially for men, which improve African Americans’ ability to cope with the long-term impact of racial discrimination. For example, African Americans who engage in more active coping report less stress in response to racial micro-aggressions (Torres et al., 2010). Another particularly effective coping method appears to be discussing discriminatory experiences with others, as this response is associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders (McLaughlin et al., 2010). A third approach that may buffer the deleterious effects of discrimination is to encourage individuals to focus on their racial identity. For example, ninth-grade African Americans who reported high racial centrality showed no association between perceived racial discrimination and psychological distress reported 2 years later (Sellers et al., 2003). In addition, African American young adults did not report an increase in willingness to use substances following a laboratory-based discriminatory experience if they engaged in a writing task that reaffirmed their racial identity (Stock et al., 2011). Although these findings are promising, conflicting studies have found that some elements of racial identity exacerbate the negative effects of discrimination (Burrow & Ong, 2010; Bynum et al., 2007). Thus, more research is required to determine how best to reduce the impact of discrimination on young African Americans and prevent the development of drinking problems.

There are several future directions worth exploring. We focused on racial discrimination as a risk factor for increased vulnerability for negative-mood–related drinking (i.e., a moderation hypothesis). Yet discrimination itself produces negative moods (Ong et al., 2009), which could lead to drinking as a coping response (Gerrard et al., 2012). This pattern of mediation has been demonstrated in longitudinal studies (e.g., Boynton et al., 2014; Gibbons et al., 2010) but has yet to be shown with micro-longitudinal data. However, we did not measure the source of negative moods and thus could not determine whether specific stressors, especially those related to race, showed unique associations with evening levels of alcohol use. Future studies, therefore, should measure racial discrimination at the daily level (i.e., daily hassles or micro-aggressions; Torres et al., 2010) to examine both moderation and mediation. Likewise, researchers should measure drinking problems at the daily level to test whether the micro-processes under investigation give rise specifically to problematic drinking.

In addition, we advise caution in generalizing these findings derived from a single HBCU; thus, replications are necessary at non-HBCUs as well as among African American noncollege young adults. Although drinking patterns are similar among African American college students regardless of type of institution (Meilman et al., 1995), other social factors (e.g., rates of discrimination) may vary among schools. Moreover, HBCUs are diverse in terms of students’ socioeconomic status (Kim & Conrad, 2006), a construct we did not measure and thus could not control for in our models. Future studies would be advised as well to examine these relations among individuals of varying ages and among other groups who experience discrimination in their everyday lives.

This study was the first to examine the moderating effects of lifetime racial discrimination on within-person associations between daily negative mood and both social and nonsocial alcohol use among a large sample of African American college students. Our findings provide evidence that the cumulative effects of a lifetime of discrimination may give rise to problematic drinking by way of shaping African American men’s response to negative moods, especially regarding alcohol use in nonsocial settings. African American women, however, showed an opposite pattern of results that requires further exploration. Future research should examine race-related stressors and problem drinking at the daily level of analysis to determine how day-to-day psychological processes may contribute to the emergence of alcohol-related problems and how this public health issue might best be remediated.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R21AA0175 84 and P20AA014643 and National Center for Research Resources Grants M01RR10284 and UL1RR031975. Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32AA007290 and P60AA03510. Ross E. O’Hara is now at Persistence Plus® LLC, Boston, MA.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S., Carney M. A., Tennen H., Affleck G., O’Neil T. P. Stress and alcohol use: A daily process examination of the stressor-vulnerability model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:979–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.5.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S., O’Hara R. E., Ehrenberg E., Sullivan T. P., Tennen H. Episode-specific drinking-to-cope motivation, daily mood, and fatigue-related symptoms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:766–774. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer L. A., Harder V. S., Rose G. L., Helzer J. E. Drinking and stress: An examination of sex and stressor differences using IVR-based daily data. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R. F., Vohs K. D., Tice D. M. The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton M. H., O’Hara R. E., Covault J., Scott D., Tennen H. A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among African American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:228–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradizza C. M., Reifman A., Barnes G. M. Social and coping reasons for drinking: Predicting alcohol misuse in adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:491–499. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodish A. B., Cogburn C. D., Fuller-Rowell T. E., Peck S., Malanchuk O., Eccles J. S. Perceived racial discrimination as a predictor of health behaviors: The moderating role of gender. Race and Social Problems. 2011;3:160–169. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9050-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G. H., Kogan S. M., Chen Y. F. Perceived discrimination and longitudinal increases in adolescent substance use: Gender differences and mediational pathways. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1006–1011. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E., Brady N., Thompson S., Tobin J. N., Cassells A., Sweeney M., Contrada R. J. Perceived racism and negative affect: Analyses of trait and state measures of affect in a community sample. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:150–173. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broudy R., Brondolo E., Coakley V., Brady N., Cassells A., Tobin J. N., Sweeney M. Perceived ethnic discrimination in relation to daily moods and negative social interactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow A. L., Ong A. D. Racial identity as a moderator of daily exposure and reactivity to racial discrimination. Self and Identity. 2010;9:383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum M. S., Burton E. T., Best C. Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American college freshmen: Is racial socialization a buffer? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:64–71. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen M., Vik P. W., Jarchow A. College student heavy drinking in social contexts versus alone. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. L., Frone M. R., Russell M., Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. L., Russell M., Skinner J. B., Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Coxe S., West S. G., Aiken L. S. The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:121–136. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell K. G., Chung T., Clark D. B., Martin C. S. Solitary alcohol use in teens is associated with drinking in response to negative affect and predicts alcohol problems in young adulthood. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:602–610. doi: 10.1177/2167702613512795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran P. J., Bauer D. J. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. K., Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M., Stock M. L., Roberts M. E., Gibbons F. X., O’Hara R. E., Weng C.-Y., Wills T. A. Coping with racial discrimination: The role of substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:550–560. doi: 10.1037/a0027711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F. X., Etcheverry P. E., Stock M. L., Gerrard M., Weng C.-Y., Kiviniemi M., O’Hara R. E. Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:785–801. doi: 10.1037/a0019880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F. X., O’Hara R. E., Stock M. L., Gerrard M., Weng C. Y., Wills T. A. The erosive effects of racism: Reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez V. M., Collins R. L., Bradizza C. M. Solitary and social heavy drinking, suicidal ideation, and drinking motives in underage college drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez V. M., Skewes M. C. Solitary heavy drinking, social relationships, and negative mood regulation in college drinkers. Addiction Research and Theory. 2013;21:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert K. C., Wenze S. J. Daily diary methods. In: Mehl M. R., Conner T. S., editors. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J. W., Hilbe J. M. Generalized estimating equations. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M. L., Corbin W. R., Fromme K. Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: A prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R., Heeren T., Winter M., Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. M., Conrad C. F. The impact of historically Black colleges and universities on the academic success of African-American students. Research in Higher Education. 2006;47:399–427. [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff E. A., Landrine H. Cross-validation of the Schedule of Racist Events. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H., Klonoff E. A. The Schedule of Racist Events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen R. J., Diener E. Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion. In: Clark M. S., editor. Emotion: Review of personality and social psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. K., Tuch S. A., Roman P. M. Problem drinking patterns among African Americans: The impacts of reports of discrimination, perceptions of prejudice, and “risky” coping strategies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:408–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays V. M., Cochran S. D., Barnes N. W. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K. A., Hatzenbuehler M. L., Keyes K. M. Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1477–1484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilman P. W., Presley C. A., Cashin J. R. The sober social life at the historically Black colleges. Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 1995;9:98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr C. D., Armeli S., Tennen H., Temple M., Todd M., Clark J., Carney M. A. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Newsletter. Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: Office of Research Translation and Communication; 2004. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Neff J. A. Solitary drinking, social isolation, and escape drinking motives as predictors of high quantity drinking, among Anglo, African American and Mexican American males. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1997;32:33–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic J., Duka T. Gender specific effects of a mild stressor on alcohol cue reactivity in heavy social drinkers. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2006;83:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong A. D., Fuller-Rowell T., Burrow A. L. Racial discrimination and the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:1259–1271. doi: 10.1037/a0015335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe E. A., Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse A. L., Todd N. R., Neville H. A., Carter R. T. Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59:1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0026208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes W. A., Peters R. J., Jr., Perrino C. S., Bryant S. Substance use problems reported by historically Black college students: Combined marijuana and alcohol use versus alcohol alone. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:201–205. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richeson J. A., Shelton J. N. Negotiating interracial interactions: Costs, consequences, and possibilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Scott L. D., Jr Correlates of coping with perceived discriminatory experiences among African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E. K., Caldwell C. H., Sellers R. M., Jackson J. S. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R. M., Caldwell C. H., Schmeelk-Cone K. H., Zimmerman M. A. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J. S., Gaher R. M., Correia C. J., Hansen C. L., Christopher M. S. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T., Bosker R. Multilevel analysis. London, England: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stock M. L., Gibbons F. X., Walsh L. A., Gerrard M. Racial identification, racial discrimination, and substance use vulnerability among African American young adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37:1349–1361. doi: 10.1177/0146167211410574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swim J. K., Hyers L. L., Cohen L. L., Fitzgerald D. C., Bylsma W. H. African American college students’ experiences with everyday racism: Characteristics of and responses to these incidents. Journal of Black Psychology. 2003;29:38–67. [Google Scholar]

- Torres L., Driscoll M. W., Burrow A. L. Racial microaggressions and psychological functioning among high achieving African-Americans: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:1074–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D., Clark L. A., Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., John D. A., Oyserman D., Sonnega J., Mohammed S. A., Jackson J. S. Research on discrimination and health: An exploratory study of unresolved conceptual and measurement issues. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:975–978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]