Abstract

Central Nervous System (CNS) vasculitis is the most common life-threatening complication of coccidioidal meningitis. It is manifested by cerebral ischemia, hemorrhage, and infarction. We report a case of CNS vasculitis in a patient receiving chemotherapy and review of the literature on coccidioidal meningitis. The patient was treated with combination antifungal therapy and a short course of high dose corticosteroids with a modest improvement in her neurological examination after initiation of steroids.

Keywords: Coccidioidal meningitis, Fungal meningitis, Steroid, Cerebral vasculitis, Disseminated coccidioidomycosis

1. Introduction

Fungal meningitis is a rare cause of meningitis and results from the spread of fungi to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The most common causes of fungal meningitis include, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Coccidioides immitis/posadasii. HIV/AIDS, Solid Organ Transplantation, high dose steroid use, malignancy, and other primary and secondary immunosuppressed states are associated with a higher risk of Coccidioides meningitis than in immunocompetent patients. [1], [2], [3] We present a case of meningitis with cerebral infarction from vasculitis as one of the manifestations of coccidioidal meningitis in a patient with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL).

2. Case

A 23-year-old woman with a history of B-cell ALL and CNS involvement presented to the emergency department with severe headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, worsening mental status, and fever for approximately one week. She had received intrathecal methotrexate a month prior to admission. Her other chemotherapy regimen included 6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, and prednisone 100 mg oral daily for 5 days at the start of the month. The patient did not have a prior history of coccidioidomycosis and no prior coccidioides serological testing. Moreover, her medical history included diabetes mellitus, deep vein thrombosis, and depression. Past surgical history included an insertion of Omaya reservoir nine months before admission for intrathecal chemotherapy, which was removed due to postoperative complications including altered mental status, intracranial, and ventricular hemorrhage. On admission, the patient was obtunded: opening eyes to verbal and tactile stimuli, following simple commands intermittently, but was otherwise unable to perform more thorough testing. Neurological Examination showed intact strength and sensation in the right upper and lower extremities, but diminished strength in the left upper extremity and left lower extremity on plantar flexion (4/5). She had diminished reflexes in upper extremities 1+ throughout bilaterally, and 0 in lower extremities bilaterally, with flexor plantar reflexs. Dysmetria was noted on the left during finger to nose.

Lumbar punctures were performed on hospital days 1, 8, 22 and 23 and the results are summarized in Table 1. Blood cultures were negative. She was initially administered intravenous vancomycin, meropenem, fluconazole, and acyclovir. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed extensive small vessel deep infarctions involving both cerebral hemispheres, the midbrain and cerebellum (see Fig. 1, Fig. 2). A right distal portion infarct of the middle cerebral artery was present. Serum Coccidioides antibodies (IgM and IgG) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (EIA) were positive. The patient was administered liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) and was continued on intravenous fluconazole (800 mg daily).

Table 1.

Cerebral spinal fluid analysis results on hospital days (HD) 1,8, 22, and 23.

| Opening pressure (mm Hg) | Glucose level (mg/dL) | Total Protein (mg/dL) | Red Blood Cells (cells/mm^3) | White Blood Cell Count (cells/mm^3) | CSF Coccidioides Ab titer by Complement Fixation | CSF Coccidioides antigen (ng/uL) | CSF culture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD 1 | 45 | 22 | 71 | 167 | 1130 | < 1:2 | 7.57 | Positive for Coccidioides immitis |

| HD 8 | 48 | 215 | 31,600 | 33 | 1.71 | Positive for Coccidioides immitis | ||

| HD 22 | 99 | 39 | 605 | 11 | 1:4 | Negative | ||

| HD 23 | 1.18 | Negative |

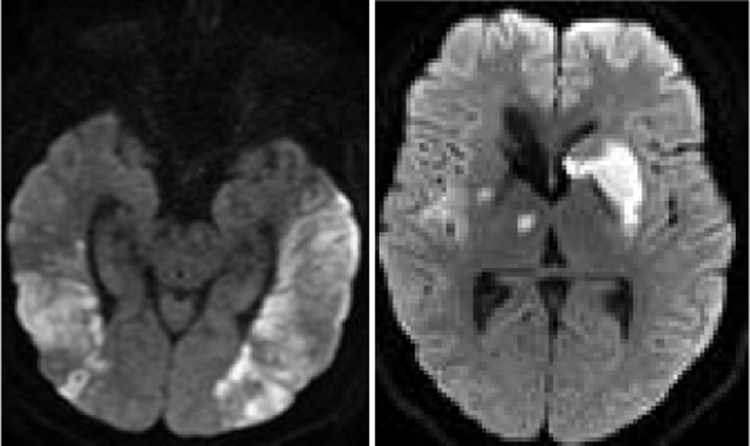

Fig. 1.

Axial diffusion weighted MR images show restricted diffusion in multiple vascular distributions within the brain consistent with infarctions.

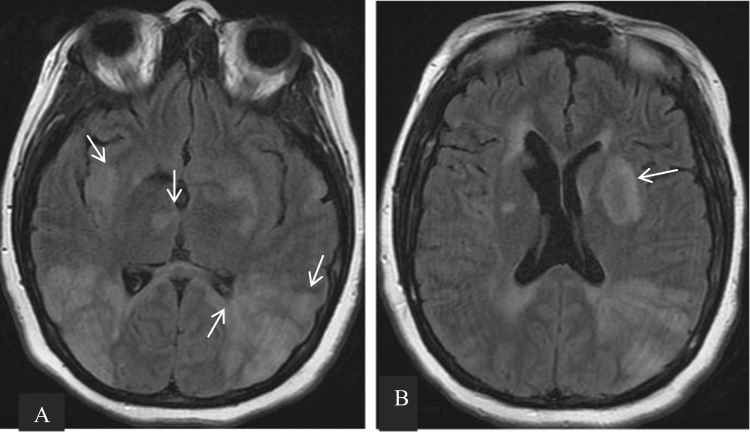

Fig. 2.

Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR image demonstrates (A) bilateral but asymmetric cortical/subcortical and basal ganglia hyperintensities. (B) Focal lesions show high signal foci that have a typical peripheral hypointense rim.

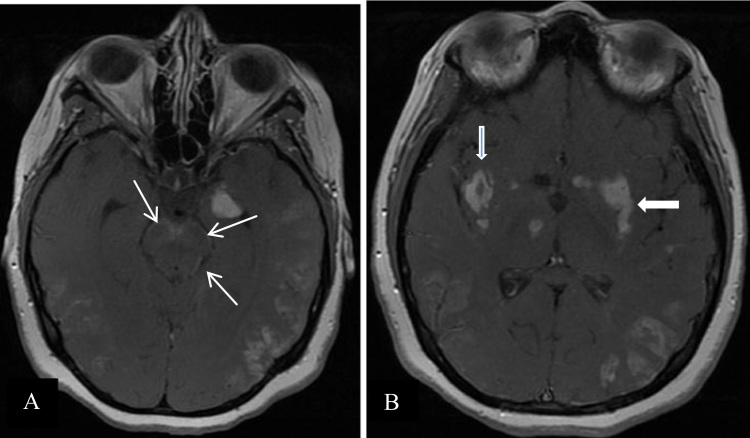

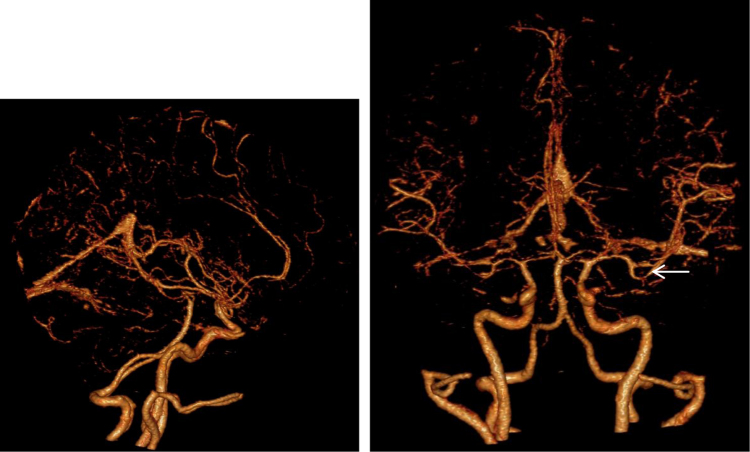

On day 8, due to the lack of clinical response and mental status deterioration, a repeat lumbar puncture (see Table 1) and MRI/ magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) were done. MRI/MRA showed: subacute infarcts involving the bilateral temporoparietal lobes, left lentiform nucleus, left medial temporal lobe, portions of the caudate head on hemisphere, right thalamus, right basal ganglia, and right insular cortex (See Fig. 2). Characteristic enhancing basilar leptomeninges and ring-like irregular enhancing focal lesions were also seen (See Fig. 3). A CT angiogram of the head and neck confirmed suspicion for vasculitis by demonstrating caliber variation of several intracranial vessels (See Fig. 4). Her neurological exam had deteriorated.

Fig. 3.

Axial T1-weighted gadolinium -enhanced MR image shows characteristic (A) diffuse enhancing basilar leptomeninges (white thin arrows) and (B) ring-like and irregular enhancement of focal lesions (thick white arrows).

Fig. 4.

CT Angiogram illustrates caliber variation of several intracranial vessels, most specifically M2 branches of the left middle cerebral artery (white arrow) indicative of vasculitis.

Micafungin and prednisone (60 mg daily) were added (on day 14 and 17, respectively) after a discussion at a multidisciplinary conference. A repeat lumbar puncture was performed (see Table 1). CSF studies showed improvement, but clinically the patient remained unchanged. She had no immediate response to steroids and they were tapered gradually. Micafungin and amphotericin were also discontinued. Fluconazole was continued and switched to oral 400 mg twice a day. Patient was discharged approximately 3 months out from her initial presentation. Prior to discharge, she displayed mild improvements in her neurological exam. She would open her eyes to verbal stimuli and was able to say short two-three word sentences. She was able to follow simple commands intermittently. Her strength had improved to 4/5 in all of her extremities; however, she still had severe cognitive deficits and significant impairments of activities of daily living.

3. Discussion

Coccidioidomycosis is the most common cause of fungal meningitis in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Western Texas. [4] Primary coccidioidomycosis affects the lung, but may spread to other organs in 0.6% of the cases. [5] Patients with dissemination are severely sick and treated with amphotericin B and/or a triazole antifungal. The use of an echinocandin in combination with amphotericin B deoxycholate has also been shown to increase survival and decrease tissue burdens of Coccidioides in mice models. [6].

The most common presentation of CNS disease is headaches, decreased cognition, and basilar meningitis. [7], [8] In a retrospective analysis of 60 patients with coccidioidal meningitis by Mathisen et al., headache was the most common presenting symptom (approximately 80% of patients) and signs of increased intracranial pressure (nausea/vomiting, papilledema) were seen in about 50% of patients - which were initial complaints of the patients. [9] MRI post-contrast can show enhancement of cervical subarachnoid space, basilar, sylvian, and interhemispheric cisterns with focal parenchymal signal abnormalities indicating ischemia or infarction. [10].

Complications of meningitis related to coccidioidomycosis include hydrocephalus, infarction, vasculitis, and abscess. Vasculitis is life threatening and is characterized by cerebral infarction due to inflammatory changes in the walls of small and medium size cerebral arteries and veins leading to vascular insufficiency and neurologic deficiencies resembling stroke. [11] Venous and dural thrombosis are rare, but have been reported. Williams PL et al., reported 10 cases of vasculitis due to coccidioidal meningitis. [12] The time to onset was less than 1 month in 5 cases, 1–2 months in 3 cases, and greater than 2 months in 2 cases. Drake et al. reported 71 cases of coccidioidal meningitis with 31% of those cases showing parenchymal brain lesions which most were believed to be secondary to vasculitis. [8].

Choice of therapy providing the most favorable outcome in coccidioidal CNS vasculitis resulting in infarction remains unsettled. Initially patients were treated with amphotericin B administered into the subarachnoid space. [13] This was prior to discovering that azoles could be used to treat meningeal disease. [14] The minimum dose is 400 mg daily, but higher doses are preferred initially −800 mg was used in our patient. The lipid preparation of amphotericin B has been shown to increase benefit in animal studies to treat coccidioidomycosis meningitis. [15] Limited data exist regarding the use of caspofungin, duration of therapy and the role of steroids in the treatment of vasculitis in patients with coccidioidal meningitis. [1], [2].

Currently, the use of steroids in the setting of vasculitic infarction is controversial although the updated Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis do mention their use. [2] Prior to a 2014 retrospective study by Thompson et al., there were no clinical studies showing clear efficacy of steroid use in the management of coccidioidal meningitis, but rather only anecdotal evidence, case reports, and expert opinion. Some experts have noted improvement with high dose glucocorticosteroids. Williams et al. reported using intravenous dexamethasone in conjunction with amphotericin B, typically within hours to days of onset of symptoms, with one reported case showing brief clinical improvement. [12] Thompson et al. showed in a multicenter retrospective study that adjunctive corticosteroid therapy, given after a documented cerebrovascular accident (CVA) attributed to coccidioides meningitis, reduced the rate of subsequent CVAs and was well tolerated with few adverse events.[16] Kern Medical Center uses dexamethaxone with a gradual taper. [5] In our case, the patient did eventually show minor improvements in mental status after the initiation of steroids, although she did not return to her baseline mental status and continues to display significant cognitive deficits.

Response to therapy can be monitored by CF titer and lumbar punctures should be obtained every six to twelve weeks. A low (<=1:4) or undetectable titer suggests control of disease. [7] However, vasculitic complications may occur despite stable cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) parameters. [12] MRI should be used to establish a baseline and monitor the course of illness especially if new neurological symptoms occur. The incidence of abnormalities detectable by imaging studies has been reported to be as high as 93% for patients with coccidioidal meningitis. [10] At the University of Arizona, it is suggested to perform imaging at the time of diagnosis, at 3 month, 6 months, and 1 year, and every 6 months thereafter until clinical and imaging stability is achieved. MR angiography can be included to evaluate for vasculitis. [17].

It is recommended that these patients be on triazole therapy for life, given the high relapse rate when therapy is discontinued. [18] The efficacy of steroids for vasculitis is unclear and needs to be further studied. Coccidioidal meningitis has a high morbidity and mortality and should be considered in the differential in immunocompromised patients who present with altered mental status or meningitis-like symptoms and live or traveled to an endemic region. Furthermore, patients should be screened for coccidioidomycosis prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, and fluconazole prophylaxis may be considered in patients actively receiving treatment for hematologic malignancies or solid organ transplantation with positive serology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgements

Banner University Medical Center Tucson, Department of Infectious Diseases.

References

- 1.Williams P.L. Vasculitic complications associated with coccidioidal meningitis. Semin Respir. Infect. 2001;16(4):270–279. doi: 10.1053/srin.2001.29319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galgiani J.N., Ampel N.M., Blair J.E. Infectious diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63(6):e112–e146. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC.GOV (Internet). Atlanta: Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Inc., 2015 (updated 2014 April 1). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/meningitis/fungal.html.

- 4.Galgiani J.N. Coccidioidomycosis: a regional disease of national importance-rethinking approaches for control. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;130(4 Pt 1):293–300. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4-199902160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson R.H., Einstein H.E. Coccidioidal meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;42(1):103–107. doi: 10.1086/497596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez G.M., Gonzalez G., Najvar L.K. Therapeutic efficacy of caspofungin alone and in combination with amphotericin B deoxycholate for coccidioidomycosis in a mouse model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:1341–1346. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.N.M. Ampel, The Treatment of Coccidioidomycosis, Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, 57, Sep 2015, 51-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Drake K.W., Adam R.D. Coccidioidal meningitis and brain abscesses: analysis of 71 cases at a referral center. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1780–1786. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34b69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathisen G., Shelub A., Truong J. Coccidioidal eningitis: clinical presentation and management in the Fluconazole Era. Medicine. 2010;89(5):251–284. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181f378a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrobel C.J., Meyer S., Johnson R.H. MR findings in acute and chronic coccidioidomycosis meningitis. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1992;13(4):1241–1245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair J.E. Coccidioidal meningitis: update on epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2009;11(4):289–295. doi: 10.1007/s11908-009-0043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams P.L., Johnson R., Pappagianis D. Vasculitic and encephalitic complications associated with Coccidioides immitis infection of the central nervous system in humans: report of 10 cases and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992;14(3):673–682. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.3.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einstein H.E., Holeman Jr.C.W., Sandidge L.L. Coccidioidal meningitis—the use of amphotericin B in treatment. Calif. Med. 1961;94(6):339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galgiani J.N., Catanzaro A., Cloud G.A. Fluconazole therapy for coccidioidal meningitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993;119(1):28–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemons K.V., Sobel R.A., Williams P.L. Efficacy of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) against coccidioidal meningitis in rabbits. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46(8):2420–2426. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2420-2426.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson G. Adjunctive corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of Coccidioidal meningitis. IDWeek 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cid/cix318. (Oct 11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erly W., Labadie E., Williams P.L. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis complicated by vasculitis: a cause of fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage in two cases. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1605–1608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewsnup D.H., Galgiani J.N., Graybill J.R. Is it ever safe to stop azole therapy for Coccidioides immitis meningitis? Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124(3):305–310. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-3-199602010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]