Highlights

-

•

The Rives-Stoppa technique is an excellent repair in midline incisional hernia.

-

•

Prospective comparative analysis between retromuscular Self-gripping mesh and PPL fixed with sutures.

-

•

Self-gripping mesh is related to less postoperative pain the first 48 h after repair.

-

•

There were more postoperative hematomas in Non-Progrip group.

-

•

There were no differences in hernia recurrence in both groups.

Keywords: Incisional hernia, Mesh repair, Self-gripping mesh, Rives-Stoppa repair, Rives technique

Abstract

Background

Rives-Stoppa repair is widely accepted technique in large midline IH, and appears to be advantageous compared to other surgical techniques concerning complications and recurrence rates. The aim of this case series study was to analyze 1-year outcomes in patients with IH treated with Progrip self-gripping mesh compared to polypropylene (PPL) mesh fixed with sutures during the Rives-Stoppa technique.

Methods

Between June 2014 and June 2015, we performed a prospective comparative non-randomized (case series) analysis between 25 patients with IH using retromuscular Progrip self-gripping mesh and 25 patients with retromuscular PPL mesh fixed with sutures, under Rives-Stoppa repair. All intraoperative and perioperative morbidities were reported with particular attention to wound infection, seroma or hematoma formation, duration of hospital stay, presence of abdominal wall pain (VAS) and recurrence during long-term follow-up.

Results

Mean operative time in Progrip group was shorter than Non-Progrip group (101 ± 29.5 versus 121 ± 39.8 min). In Progrip group, the only postoperative complication was seroma in two patients; however, in Non-Progrip group, we reported seroma in three patients, and hematoma in 4 patients (p = 0.03). The median hospital stay was shorter in Progrip group (5.8 ± 2.2 days versus 6.6 ± 2.9 days). Mean VAS score in the first 48 h was higher in Non-Progrip group than Progrip group (4.9 ± 2.1 versus 8.1 ± 2)(p = 0.01). The median follow-up was 13 months (range 12–20 months) and none of the 50 patients had a hernia recurrence.

Conclusions

In Rives-Stoppa repair, retromuscular Progrip mesh causes less postoperative pain in the first 48 h and lower rate of hematoma than PPL mesh fixed with sutures in the short term follow-up.

1. Introduction

Incisional hernias (IH) are a common problem in abdominal surgery that contributes to chronic pain, decreased quality of life, and significant healthcare costs [1]. IH develop in 4% to 11% of patients after abdominal operations and may occur with a high frequency in cases of postoperative wound infection [2].

With the development of new prosthetic materials, minimally invasive techniques and improvement of open surgical procedures, it has been debated which type of technique is the best for IH repair. The Rives-Stoppa technique is widely accepted for repair of large IH, especially in midline, and appears to be more advantageous compared to other surgical techniques concerning postoperative complications and recurrence rates [3], [4], [5]. This repair has achieved several objectives: a tension-free closure due to extensive overlap between the prosthesis and the fascial edges, and the mesh placement next to the vascular-rich rectus muscles facilitates tissue incorporation and promotes resistance to prosthesis infection [6], [7]. Although the use of retromuscular mesh can reduce the recurrence rates to 1–15%, it may also cause complications, such as seroma, hematoma and chronic pain [8]. Causes of recurrence and postoperative pain after Rives-Stoppa repair are multifactorial and may be related to mesh placement technique, mesh type, or mesh fixation method. So, it is hypothesized that chronic pain is associated with suture-related nerve entrapment or suture-induced nerve irritation due to fixation of the mesh by sutures.

A self-gripping mesh (ProGrip™, Covidien, Trevoux, FRA) has been developed to achieve secure, long-term abdominal wall reinforcement without the need for additional permanent fixation. This mesh combines the properties of a lightweight mesh with a surface coverage of absorbable, polylactic acid micro-hooks for mesh fixation to the tissue. Promising clinical outcomes have been reported with this mesh in inguinal hernia [9], [10], but only two studies in literature are available regarding the use of a self-gripping mesh in IH repair [11], [12]. No published series have compared the use of this mesh with other type of fixation of polypropylene (PPL) prosthesis in patients with IH under Rives-Stoppa repair.

Therefore, the objectives of the study were to evaluate the safety and feasibility of the Parietex™ Progrip mesh in a retromuscular position, and to analyze 1-year outcomes in patients with IH, treated with this mesh compared to PPL mesh fixed with sutures in the Rives-Stoppa technique.

2. Methods

This work has been reported in line with the process criteria [13].

2.1. Patients

Between June 2014 and June 2015, a prospective cohort (case series) study with 50 consecutive patients with midline IH underwent Rives-Stoppa repair was performed at a tertiary Universitary Hospital. We carried out a comparative analysis between 25 patients using retromuscular Progrip self-gripping mesh and 25 patients with retromuscular PPL mesh fixed with sutures. The main entry criteria were adults with midline hernia classified as M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, plus W2, according to European Hernia Society (EHS) classification [14], which required primary elective repair. Exclusion criteria included lateral hernia (L1, L2, L3 or L4), signs of infection, strangulated or irreducible hernia, and emergency situations.

All hernias were diagnosed based on clinical examination and a CT scan was performed in all patients. Demographic variables including patient́s age and sex were collected. The following data were analysed: Body Mass Index (BMI), smoking, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, American Society of Anaesthesiologists score (ASA), hernia characteristics, number/type of previous repairs, indication of repair, defect size and mesh size. All intraoperative and perioperative morbidities were reported with particular attention to wound infection, prosthesis infection, seroma or hematoma formation, duration of hospital stay and presence of abdominal wall pain during long-term follow-up. We reported postoperative complications by Clavien-Dindo classification [15]. Pain was measured by visual analogue scale (VAS) on the first days after surgery during the patient́s hospitalization, and in the first and third months of follow-up. Number of analgesics during this period was also recorded. Long-term readmission or referral to another hospital were checked through the hospital database. Main outcomes included pain severity from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst imaginable pain) scale (VAS), adverse events, and hernia recurrence.

This study was approved by the our Hospitaĺs Ethics Committee.

2.2. Procedures

The Rives-Stoppa technique was used in all procedures [16]. All patients were evaluated preoperatively by an anaesthesiologist, and respiratory tests were carried out in some cases. All patients underwent abdominal repair under general anesthesia with antibiotic and thromboembolic prophylaxis, and abdominal bandage during the immediate postoperative period. Five surgeons dedicated to hernia repair and members of Unit of the Abdominal Wall Surgery performed all surgical repairs.

Each operation started with a limited midline incision, excising the previous scar back to healthy skin and exposing the hernia sac and its associated fascial defect. Herrnia sac dissection was performed in all patients, followed by lysis of intraperitoneal adhesions; this sac was preserved whenever possible to provide another layer of autogenous tissue interposed between intraperitoneal contents and the posterior surface of the prosthesis. In case of multiple defects, all individual ones were connected to create one defect. The abdominal fascial level between the rectus muscle and the posterior sheath (or, when below the arcuate line, the transversalis fascia) was dissected to create space for the mesh, usually 5–10 cm from the margins of hernia. During the dissection we tried to preserve epigastric vessels and nervous pedicle. Dissection was carried out laterally to, at least, the midclavicular line or even further laterally underneath the external or internal oblique muscles to the anterior axillary line, depending on the size of the hernia and the presence or condition of the ipsilateral rectus muscle. The posterior fascia and peritoneum were closed using a slowly absorbable suture.

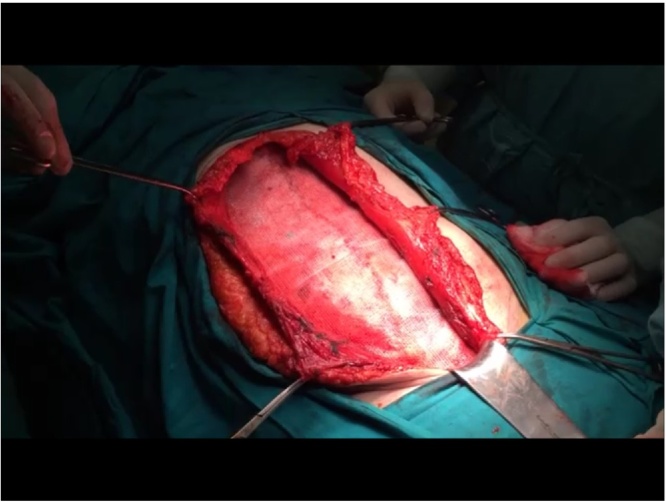

In one group of patients (Non-Progrip group), a PPL mesh was placed using sublay technique over the posterior sheath of the abdominis rectus muscle and was minimally fixated in four quadrants through the muscle with non-absorbable sutures. In another group (Progrip group), the self-adhesive mesh was placed over the closed posterior fascia but underneath the abdominal rectus and oblique muscles (Fig. 1). No additional sutures or tackers were used to fixate the mesh in this group.

Fig. 1.

Progrip mesh in retromuscular position during Rives-Technique repair.

The anterior fascia was closed using a slowly absorbable suture. In all cases two Jackson-Pratt drainage tubes were used, one placed retromuscular and another in a supraaponeurotic position. Drains were removed once the output had decreased markedly.

Standard postoperative care included patient controlled analgesia for pain management and perioperative subcutaneous heparin. Patients were followed up at 1, 3, 6 months and 1 year after surgery, including patient interview and physical examination, by the operating surgeon.

2.3. Data analysis

Statistical analysis were performed with the SPSS statistical software package (IBM SPSS for Windows, Version 21.0). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (± SD) or range, and categorical variables were presented as n (%). Univariate analysis was performed using “t-Student” to explore quantitative variables and “Chi square” (or Fisher test) if they were dichotomous. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 50 patients with IH were treated by the Rives-Stoppa technique at a tertiary Hospital between June 2014 and June 2015. Table 1 shows demographic variables in both groups. Among the 50 patients, there were 27 women (54%) and 23 men (46%). The median age was 54.9 years (range 34–71).

Table 1.

Demographics in both groups.

| Variables | Progrip Group N = 25 |

Non-Progrip Group N = 25 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 53.6 ± 25.5 | 55.3 ± 21.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 (44) | 12 (48) |

| Female | 14 (56) | 13 (52) |

| BMI | ||

| >30 | 3 (12) | 4 (16) |

| ≤30 | 22 (88) | 21 (84) |

| Smoking | ||

| yes | 4 (16) | 3 (12) |

| no | 21 (84) | 22 (88) |

| ASA classification | ||

| I | 12 (48) | 8 (32) |

| II | 12 (48) | 14 (56) |

| III | 1 (4) | 3 (12) |

| Previous abdominal wall hernia repair | ||

| yes | 4 (16) | 5 (20) |

| no | 21 (84) | 20 (80) |

| Hernia defect location (EHS class.) | ||

| M2M3M4W2 | 12 (48) | 11 (44) |

| M3M4W2 | 12 (48) | 13 (52) |

| M3W2 | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Mean hernia defect size (cm2) | 86 ± 28 | 85 ± 22 |

The median total BMI was 28.1 kg/m2 (range: 24.7–31.3 kg/m2). At the time of repair, 7 patients (14%) reported smoking and twenty patients (40%) were ASA class I, twenty-six (52%) were class II and four (8%) was class III.

All IH were located on the abdominal midline, classified according to EHS types in M3W2, M3M4W2 or M2M3M4W2. The mean hernia defect size was 86 ± 28 cm2 in Progrip group versus 85 ± 22 cm2 in Non-Progrip group. Forty-one patients were diagnosed with an IH and nine (36%) had a recurrence after previous hernia repair.

Mean operative time in Progrip group was shorter than Non-Progrip group (101 ± 29.5 versus 121 ± 39.8 min)(Table 2). In 22 procedures, the size of the mesh was 30 × 15 cms; in the other 28 cases, a smaller mesh of 20 × 15 cms was placed in order to gain a minimum overlap of 5 cm. All complications were grade 1 according to Clavien-Dindo classification. In Progrip group, the only postoperative complication was seroma in two patients, which was treated with percutaneous punction in one case, and in another patient, with conservative management. However, in Non-Progrip group, we reported seroma in three patients, and hematoma in 4 patients (p = 0.03): one of this group needed a reoperation to solve the hematoma.

Table 2.

Intraoperative and postoperative variables in both groups.

| Variables | Progrip Group N = 25 |

Non-Progrip Group N = 25 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average operative time | 101 ± 29.5 | 121 ± 39.8 | NS |

| Type of Prosthesis | PROGRIP | PPL | |

| Prosthesis size | |||

| Standard (20x15 cms) | 16(55.6) | 12 (44.4) | NS |

| Large (30x15 cms) | 9 (44.4) | 13 (55.6) | |

| Postoperative complications (grade 1)* | |||

| TOTAL | 2 (11.1) | 7 (27.3) | 0.03 |

| Seroma | 2 (11.1) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Hematoma | – | 4 (16.2) | |

| Infection | – | – | |

| Neuralgia | – | – | |

| Recurrence (follow-up 13 months) | – | – | NS |

| Pain score during hospitalization | |||

| VAS < 48 h from surgery | 4.9 ± 2.1 | 8.1 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| VAS > 48 h from surgery | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ± 3.5 | |

| Pain score during ambulatory follow-up | |||

| First month | 2.1 ± 1 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | NS |

| Third month | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 1 | |

| Six month | 0 | 0 | |

| Median Hospital stay(days) | 5.8 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 2.9 | NS |

*Postoperative complications according to Clavien Dindo classification.

The median hospital stay was shorter in Progrip group (5.8 ± 2.2 days versus 6.6 ± 2.9 days). One patient had an extended hospital stay of 9 days because of postoperative ileus, treated conservatively. Mean VAS score in the first 48 h was higher in Non-Progrip group than Progrip group (4.9 ± 2.1 versus 8.1 ± 2)(p = 0.01) (Table 2). The median follow-up was 13 months (range 12–20 months) and patient follow-up compliance through 1 year was 100%. None of the 50 patients had a hernia recurrence, and there were no infectious complications directly related to the used prosthesis. No patient was readmitted during this period. After 2-month follow-up, all patients had returned to normal daily activities.

4. Discussion

This prospective study of 50 consecutive patients with IH is the first one to compare outcomes between a self-gripping prosthesis and a PPL mesh fixed with sutures in the Rives-Stoppa technique. According to our results, Progrip mesh placed in a retromuscular position causes less postoperative pain in the first 48 h and lower rate of hematoma than PPL mesh fixed with sutures in the short term follow-up.

Our experience, developed through different techniques, shows that the Rives-Stoppa technique offers guaranties for optimal repair of midline IH with low recurrence and complication rates. This repair uses a strategically placed mesh with wide overlap of the hernia defect to create a tension-free closure and optimize tissue incorporation of the mesh into the abdominal wall. This procedure allows good cosmetic results [4]: skin necrosis is rare because the plane dissection is minimal in the suprafascial area, with minimum subcutaneous dissection. It is also preserved the functionality and integrity of the abdominal wall, and mesh placement between the posterior sheath and abdominal muscles uses intraabdominal pressure to ensure its fixing in this location [7]. Additionally, placement of the prosthesis adjacent to the highly vascularised rectus abdominis muscle may also minimize the possibility of infection [17]; mesh infection can be a devastating complication that inevitably leads to hernia recurrence if mesh explantation is necessary. Therefore, a sublay mesh protects the mesh from exposure from superficial wound complications, intra-abdominal adhesions, and contamination.

Self-gripping implants are promoted to combine the advantages of atraumatic fixation with improved handling and reduced costs. These meshes in open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair have already shown promising results, including lower infection rates, less chronic pain and lower recurrence rates [9], [10], [11], [12], [18], [19], [20], [21]. Our study demonstrates that the ProGrip mesh is a safe and effective treatment option to facilitate durable open repair of IH. These outcomes compare favourably to previous studies in similar patient populations. Recently published data show a significant reduction in pain after inguinal hernia repair in the first week postoperatively [22]. A case series of 21 patients with IH treated with open repair using ProGrip mesh reported excellent outcomes through 6 months follow-up [12]. Same results were obtained with the use of Progrip mesh in 28 patients with IH who underwent Rives-Stoppa repair [11]. Verhelst et al. reported that 23 patients (82%) did not have any pain at their final outpatient clinic visit; none of the 28 patients developed a recurrence during 1 year follow-up.

In our study, self-gripping mesh was well tolerated and reduced a little bit early postoperative pain within the first 48 h, without increasing the risk of early recurrence. However, there were no significant differences in the late postoperative pain in the first, third and sixth months or in the rate of recurrence between both study groups. Causes of postoperative pain are multifactorial and may include inflammatory reaction to mesh, iatrogenic nerve injury or entrapment, or issues related to mesh tension due to additional suture or tack fixation [23]. Our experience suggests that the use of a self gripping mesh using retromuscular technique offers a durable repair without the need for additional permanent fixation that may cause persistent pain. In Non-Progrip group, we fixated minimally the PPL mesh in the sublay position with a non-absorbable suture to facilitate the prosthesis placement. We think this fixation does not contribute to the repair consistency, but this gesture would be able to cause the possibility of the postoperative pain [24]. This is consistent with what has been described in the open inguinal hernia procedure using Progrip mesh [9], [19], [20], [21], [25]. There is also evidence that some postoperative discomforts in ventral hernia surgery are caused by fixation sutures or staples [22]. In our study, suture-fixed meshes showed a significantly higher pain score on the postoperative days, and these differences remained valid during the first 48 postoperative hours. However, there were no differences in pain score during ambulatory follow-up.

The use of a self-gripping mesh has also proved to be a safe procedure, as five patients in this study had a mesh related adverse event. Postoperative hematoma was the most frequent complication in Non-Progrip group (16.2%). This is slightly higher compared to previously reported rates (4–15%) for hematoma in open IH repair [6], [8]. This finding could be caused by the accidental damage during mesh fixation with sutures due to high vascularization of the rectus muscle, especially epigastric vessels and its branches. There were no important differences about postoperative seroma findings in both groups; our group kept all drains during the whole hospitalization period to minimize probability of its formation, regardless of the study group.

Duration of surgery with self-fixating meshes is shorter [11], [12]. Because the studies in groin hernia repair show a reduction in duration of the surgical procedure, it is expected that the use of this self-gripping mesh in open IH repair may also reduce it significantly. According to our results, the operative time is lower, which is a considerable fact with regard to economic as well as the beneficial aspects for the patients.

Although previous studies have also demonstrated a wide variation of recurrence rates 0–30% for IH repair using mesh in retro-muscular position, sublay repair had the highest probability of having the lowest rate of hernia recurrence and surgical site infection [7]. In our serie of 50 cases, we had no hernia recurrence with a mean follow-up of 13 months. Therefore, after our analysis, the possibility of recurrence does not depend on the type of fixation of the mesh, although all risk factors have not been studied and they were not our objective of study.

A limitation of this study is that the follow-up of Progrip mesh was relatively short compared to other studies with a longer follow-up [18], [19], [20], [21]. Although one-year follow-up is too short a period to detect recurrences, the authors think most adverse events like postoperative complications and recurrences due to the use of the self-gripping mesh will occur in the first 3–6 months. Also, this current analysis is limited for not being randomised: although the technique was developed prospectively, the choice of Progrip or PPL mesh depended on the surgeon's preference. Thus, there are surgeons in our Unit that use self-gripping mesh preferentially in other hernia repairs, like groin hernia, and other surgeons prefer using PPL with sutures fixation methods.

In conclusion, Rives-Stoppa repair using a self-gripping mesh is a viable treatment option in patients with IH. This study shows that the Progrip mesh placed in a retromuscular position causes less postoperative pain in the first 48 h and lower rate of hematoma than PPL mesh fixed with sutures in the short term follow-up. However, longer-term randomized data are required to assess better the benefits of this approach compared with the other available techniques.

Conflicts of interest

No.

Source of funding

No.

Ethical approval

No.

Research registration

1319.

Author contributions

José Bueno-Lledó, Ph.D. – Author; study design.

Antonio Torregrosa, Ph.D. – Data collection.

Brenda Arguelles, M.D. – Data collection and data analysis.

Fernando Carbonell, Ph.D. – Writing.

Providencia García, M.D. – English traduction.

Santiago Bonafé, M.D. – Writing.

José Iserte, M.D. – English traduction.

Guarantor

Jose Bueno-Lledó.

References

- 1.Poulose B.K., Shelton J., Phillips S., Moore D., Nealon W., Penson D., Beck W., Holzman M.D. Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: making the case for hernia research. Hernia. 2012;16:179–183. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz U.A., Winkler M.S., Hartel R.W., Fleischhacker A., Wiegering A., Isbert C., Jurowich C., Heuschmann P., Germer C.T. Importance of recurrence rating, morphology, hernial gap size, and risk factors in ventral and incisional hernia classification. Hernia. 2014;1:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer J.J., Harris M.T., Gorfine S.R., Kreel I. Rives-Stoppa procedure for repair of large incisional hernias: experience with 57 patients. Hernia. 2002;6:120–123. doi: 10.1007/s10029-002-0071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iqbal C.W., Pham T.H., Joseph A., Mai J., Thompson G.B., Sarr M.G. Long-term outcome of 254 complex incisional hernia repairs using the modified Rives-Stoppa technique. World J. Surg. 2007;31:2398–2404. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger J.W., Luijendijk R.W., Hop W.C., Halm J.A., Verdaasdonk E.G., Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann. Surg. 2004;240(4):578–583. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141193.08524.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrabi M., Jangjoo A., Tavoosi H., Kahrom M., Kahrom H. Long-term outcome of Rives-Stoppa technique in complex ventral incisional hernia repair. World J. Surg. 2010;34:1696–1701. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McLanahan D., King L.T., Weems C., Novotney M., Gibson K. Retrorectus prosthetic mesh repair of midline abdominal hernia. Am. J. Surg. 1997;173:445–449. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timmermans L., de Goede B., van Dijk S.M., Kleinrensink G.J., Jeekel J., Lange J.F. Meta-analysis of sublay versus onlay mesh repair in incisional hernia surgery. Am. J. Surg. 2014;207(6):980–988. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van‘t Riet M., Steyerberg E.W., Nellensteyn J. Meta-analysis of techniques for closure of midline abdominal incisions. Br. J. Surg. 2002;89:1350–1356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders D.L., Nienhuijs S., Ziprin P., Miserez M., Gingell-Littlejohn M., Smeds S. Randomized clinical trial comparing self-gripping mesh with suture fixation of lightweight polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. Br. J. Surg. 2014;101:1373–1382. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chastan P. Tension-free open hernia repair using an innovative self-gripping semi-resorbable mesh. Hernia. 2009;13:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verhelst J., de Goede B., Kleinrensink G.J., Jeekel J., Lange J.F., Van Eeghem K.H.A. Open incisional hernia repair with a self-gripping retromuscular Parietex mesh: a restrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2015;13:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopson S.B., Miller L.E. Open ventral hernia repair using Progrip self-gripping mesh. Int. J. Surg. 2015;23:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rammohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P., the PROCESS group The PROCESS statement: preferred reporting of case series in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muysoms F., Miserez M., Berrevoet F. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13(4):407–414. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0518-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dindo D., Demartines N., Clavien P.A. Classification of surgical complications. A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rives J., Pire J.C., Flament J.B., Palot J.P. Major incisional hernias. In: Chevrel J.P., editor. Surgery of the Abdominal Wall. Springer Verlag New York; Berlin, Heildelberg: 1987. pp. 116–144. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albino F.P., Patel K.M., Nahabedian M.Y., Sosin M., Attinger C.E., Bhanot P. Does mesh location matter in abdominal wall reconstruction? A systematic review of the literature and a summary of recommendations. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013;132:1295–1304. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingsnorth A., Gingell-Littlejohn M., Nienhuijs S., Schule S., Appel P., Ziprin P., Eklund A., Miserez M., Smeds S. Randomized controlled multicenter international clinical trial of self-gripping ParietexProGrip polyester mesh versus lightweight polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: interim results at 3 months. Hernia. 2012;16:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0900-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birk D., Hess S., Garcia-Pardo C. Low recurrence rate and low chronic pain associated with inguinal hernia repair by laparoscopic placement of ParietexProGrip mesh: clinical outcomes of 220 hernias with mean follow-up at 23 months. Hernia. 2013;17:313–320. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronka K., Vironen J., Kossi J., Hulmi T., Silvasti S., Hakala T., Ilves I., Song I., Hertsi M., Juvonen P., Paajanen H. Randomized multicenter trial comparing glue fixation self-gripping mesh, and suture fixation of mesh in Lichtenstein hernia repair (FinnMesh study) Ann. Surg. 2015;262:714–720. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porrero J.L., Castillo M.J., Perez-Zapata A., Alonso M.T., Cano-Valderrama O., Quiros E., Villar S., Ramos B., Sanchez-Cabezudo C., Bonachia O., Marcos A., Perez B. Randomised clinical trial: conventional Lichtenstein vs hernioplasty with self-adhesive mesh in bilateral inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia. 2015;19:765–770. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapischke M., Schulze H., Caliebe A. Self-fixating mesh for the Lichtenstein procedure—a prestudy. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2010;395:317–322. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batabyal P., Haddad R.L., Samra J.S., Phil D., Wickins S., Sweeney E., Hugh T.J. Inguinal hernia repair with Parietex ProGrip mesh causes minimal discomfort and allows early return to normal activities. Am. J. Surg. 2016;211:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franneby U., Sandblom G., Nordin P., Nyren O., Gunnarsson U. Risk factors for long-term pain after hernia surgery. Ann. Surg. 2006;244(2):212–219. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000218081.53940.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paajanen H. Do absorbable mesh sutures cause less chronic pain than nonabsorbable sutures after Lichtenstein inguinal herniorraphy? Hernia. 2002;6:26–28. doi: 10.1007/s10029-002-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]