Abstract

Objectives

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by loss of motor neurons, resulting in progressive muscle weakness, paralysis and death within five years of diagnosis. About 10% of cases are inherited, of which 20% are due to mutations in the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene. Riluzole, the only FDA approved ALS drug, prolongs survival by only a few months. Experiments in transgenic ALS mouse models have shown decreasing levels of mutant SOD1 protein as a potential therapeutic approach. We sought to develop an efficient AAV mediated RNAi gene therapy for ALS.

Methods

A single stranded AAV9 vector encoding an artificial microRNA against human SOD1 was injected into the cerebral lateral ventricles of neonatal SOD1G93A mice and impact on disease progression and survival assessed.

Results

This therapy extended median survival by 50% and delayed hindlimb paralysis, with animals remaining ambulatory until the humane endpoint, which was due to rapid body weight loss. AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice showed reduction of mutant human SOD1 mRNA levels in upper and lower motor neurons and significant improvements in multiple parameters including the numbers of spinal motor neurons, diameter of ventral root axons, and extent of neuroinflammation in the SOD1G93A spinal cord. Mice also showed previously unexplored changes in pulmonary function, with AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice displaying a phenotype reminiscent of patient pathophysiology.

Interpretation

These studies clearly demonstrate that an AAV9-delivered SOD1-specific artificial microRNA is an effective and translatable therapeutic approach for ALS.

Keywords: ALS, AAV, artificial RNAi, microRNA, gene therapy

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by loss of corticospinal (upper) and spinal (lower) motor neurons. The majority of ALS cases are of unknown etiology (sporadic ALS), but approximately ten percent of cases are inherited (familial ALS) resulting from mutations in a rapidly expanding set of genes (1). Twenty percent of familial ALS cases are caused by mutations in superoxide dismutase (SOD1), the first gene to be linked to ALS (2). Multiple pathways have been implicated in mutant SOD1 associated neurodegeneration, including mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress response, alterations in synaptic transport, glutamate excitotoxicity, and impairment of the proteasome and autophagy (3–5). Furthermore, it is now clear that non-neuronal cells such astrocytes and microglia are determinants of the rate of motor neuron degeneration in ALS (6–8). Although the exact molecular mechanisms of disease progression have not been fully elucidated, many research findings are consistent with the hypothesis that conformational instability and misfolding of the SOD1 protein are critical in the pathogenesis of mutant SOD1 mediated familial ALS, and possibly some cases of sporadic ALS.

Transgenic B6/SJL mice expressing high levels of mutant human SOD1G93A (hSOD1) are commonly used as an ALS mouse model (9) because it recapitulates human ALS pathophysiology, including motor neuron loss, axonal degeneration, muscle denervation, gliosis, and limb paralysis. Numerous approaches have been explored to silence SOD1 in vivo including viral vector mediated delivery of inhibitory short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (10) and artificial microRNA (amiR) (11), single chain antibodies (12), and antisense oligonucleotides (13, 14).The most successful therapeutic outcome to date was obtained with a rabies pseudotyped lentivirus vector encoding an shRNA against hSOD1 injected into multiple muscles in seven day old SOD1G93A mice, which subsequently survived approximately to 270 days of age (15). AAV vectors are exceptionally efficient for gene transfer to the central nervous system (CNS) where they mediate long-term gene expression with no apparent toxicity. AAV vectors delivered through an intracerebral ventricular (ICV) injection are exceptionally efficient at transducing diverse neuronal and non-neuronal cell populations throughout the CNS (16, 17). The latest generation of AAV vectors based on AAV9 and AAVrh10 capsids transduces multiple cell types in the spinal cord, including motor neurons, at high efficiency (18, 19). This broad tropism in the spinal cord is especially important, as misfolded hSOD1 is ubiquitously expressed (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes) and non-neuronal mutant hSOD1 expression adversely impacts outcome in this disease (20). In these studies, we investigated the therapeutic efficacy of an AAV9 vector encoding a hSOD1-specific amiR (amiRSOD1) infused into the cerebral lateral ventricles of neonate SOD1G93A mice.

Materials and Methods

Vector design

Our single-stranded AAV vector contains a chicken beta actin (CBA) promoter that drives the expression of a green fluorescent protein (GFP), followed by two tandem amiRSOD1s in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) between the GFP stop codon and the Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus Posttranscriptional Regulatory Element (WPRE). The amiRSOD1 targets the coding sequence of the human SOD1 gene, is based on the Invitrogen Block-iT PolII miR vector system, originally developed in the laboratory of David Turner (US Patent No 2004/0053876), and uses the endogenous murine miR-155 flanking sequences (21). The full tandem sequence is as follows, with the guide strand underlined and the spacer sequence in bold letters: CCTCTTGCTGAAGGCTGTATGCTGATGAACATGGAATCCATGCAGGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACCTGCATGGTCCATGTTCATCAGGACACAAGGCCTGTTACTAGCACTCACATTGGCCCA GATCCTCTGCTGAAGGCTGTATGCTGATGAACATGGAATCCATGCAGGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACCTGCATGGTCCATGTTCATCAGGACACAAGGCCTGTTACTAGCACTCACATTGGCC. The original cloning was done using annealed primers, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), restriction enzymes and ligation. The subsequent transfer of the tandem amiRSOD1s into our plasmid was done using PCR and InFusion PCR cloning (Clontech). AAV9-amiRSOD1 vector was prepared by triple transient transfection of 293T cells followed by purification using iodixanol gradient centrifugation as described (22). The vector titer was determined by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) with primers and probe to the polyadenylation signal as described in (16) and determined to be 2.5e13 vg/ml.

Mice

B6SJL-Tg(SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J (The Jackson Laboratory, stock# 002726) and non-transgenic (NTG) littermates were used in these experiments. Mice were housed with 12 hour light/dark cycles, and fed a standard lab diet. Mice were genotyped using RT-qPCR, using the Jackson Laboratory protocol. AAV9-amiRSOD1 vector was injected bilaterally into the cerebral lateral ventricles of postnatal day one mice as described (16). Post-natal day 0–1 mice received two microliters of undiluted vector stock per cerebral lateral ventricle. The therapeutic vector was injected in 22 neonatal ALS SOD1G93A mice. Untreated SOD1G93A mice (n=18), AAV9-treated NTG B6/SJL mice (n=12) and untreated NTG B6/SJL mice (n=12) were used as controls. SOD1G93A mice were observed weekly for paralysis, and sacrificed at the humane endpoint (EP), when no longer able to right themselves within 15 seconds of being placed on their side, or due to sudden weight loss and hunched posture. Mice were euthanized and organs were removed and immediately frozen, or fixed in 10% formalin, or 2.5% gluteraldehyde. Four mice from each group were sacrificed for histological and biochemical studies at 135 days, the median age of survival of untreated SOD1G93A mice. The remaining 18 AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice were followed until euthanized at the humane endpoint. AAV9-treated and untreated NTG B6/SJL mice (8 per group) were euthanized at 260 days, well past the age of the longest surviving AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mouse. Histological and biochemical studies were also performed in tissues from AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at endstage and 260 day-old NTG controls. All assays included at least 3 mice per group.

RT-qPCR

RNA was isolated with TRIzol® (Invitrogen) and Direct-zol RNA Mini Prep Kit (Zymogen), then transcribed into complementary DNA using the High Capacity RNA to cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems). RT-qPCR was carried out using Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) for human SOD1 (Hs00533490_m1), mouse SOD1 (Mm01344233_g1), mouse SLC25A12 (Mm00552467_m1), mouse GFAP (Mm01253033_m1), mouse Cybb (Mm01287743_m1) and mouse Tyrobp (Mm00449152_m1). Mouse HPRT (Mm01545399_m1) was used to normalize all genes since the Ct remained stable across groups as described (23), and as observed in our experiments.

Relative expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt based on the Livak and Schmittgen method (24). Standard deviation was calculated based on the ΔCt for each sample in a group. The positive and negative errors were calculated by 2− (ΔΔCt ± standard deviation). Results are reported as mean ± error.

Immunostaining

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin overnight, then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Tissues were then embedded in OCT (TissueTek), and floating sections were cryosectioned at 20μm. Tissues were permeabalized and blocked in 5% Normal Goat Serum in PBS with 0.5% TritonX for two hours. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in PBS with 3% Normal Goat Serum. Primary antibody incubation was done overnight, and dilutions were as follow: rabbit anti GFP (1:1000, Molecular Probes, A11122), mouse anti NeuN (1:1000, Chemicon, MAB 377), rabbit anti GFAP (1:500, Invitrogen, 18-0063), rabbit anti Iba1 (1:1000, Wako, 019-19741), goat anti ChAT (1:500, Millipore, AB144), rat anti Ctip2/Bcl11B (1:500, Abcam, ab18465, clone [25B6]). Secondary antibodies were used against the appropriate species: AlexaFluor 488, 555, 647 (1:1000, Invitrogen). DAB staining was performed with the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Ctip2 staining was performed as in (25). We assessed neuromuscular junction denervation status by immunostaining for pre- and post-synaptic markers, rabbit anti-neurofilament-200 (1:160, Sigma-Aldrich, N4142,) and α- bungarotoxin conjugated to Alexa-555 (1:50, Molecular probes, B35451), respectively. For all immunostaining analysis, at least 6 sections were imaged per mouse, with each section at least 160μm apart.

Electrophysiology and Electromyography

Electrophysiological recordings were performed as described (26). In summary, recordings for the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and motor unit number estimates (MUNEs) were obtained from the gastrocnemius after stimulation of the sciatic nerve, using a portable electrodiagnostic system (Cardinal Synergy). For the MUNE recordings, the incremental technique was used. Needle electromyography was performed as previously described (27). In summary, potentials were recorded from several sites of the hindlimb muscles with a concentric needle electrode, and scored from 0–5 with 0 being a normal muscle, and 5 being a muscle displaying fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves at all sites measured.

Plethysmography

Ventilation was quantified using whole-body plethysmography in unrestrained, unanesthetized mice. Mice were placed inside a 3.5″ × 5.75″ Plexiglas chamber which was calibrated with known airflow and pressure signals before data collection. Data were collected in 10-second intervals and the Drorbaugh and Fenn equation was used to calculate respiratory volumes including tidal volume and minute ventilation. During the acclimation and baseline period of 2 hours, mice were exposed to normoxic air (FiO2: 0.21; nitrogen balance). At the conclusion of the baseline period, the mice were exposed to a brief respiratory challenge, which consisted of a 10-minute hypercapnic exposure (FiCO2: 0.07; FiO2: 0.21; nitrogen balance).

Computerized tomography (CT) scan

CT scans were performed on a Bioscan NanoSPECT/CT in the Small Animal Imaging Core at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Image processing and measurements were done using DICOM software. Measurements were done on the region immediately above the diaphragm, as determined by the disappearance of the diaphragm from the CT scan image. Chest volume was measured by tracing the whole body in this region. The height of the area analyzed was of 1mm.

RNAscope

In situ hybridization was done using RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics), a fluorescent in situ hybridization technique that uses branched DNA probes. Probes were designed by ACD, to identify mRNA for human SOD1 (410061-C2), mouse ChAT (410071-C3), GFP (400281), and mouse Etv1 (433281-C3). Twenty-micron fresh frozen spinal cord and brain sections were used for multiplex in situ hybridization performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of Motor Neurons

Two different staining methods were used to quantify motor neurons in the spinal cord: ChAT or cresyl violet staining. ChAT-positive cells were counted in at least 12 ventral horns per mouse, for 4–6 mice per group. Cresyl violet positive cells > 250um2 in the ventral horn were considered motor neurons (28). Positive cells were counted in at least 6 ventral horns, for at least 5 mice per group. Cell size was determined using MetaMorph© software (Molecular Devices).

Quantification of ventral root axons

Ventral roots of the lumbar spinal cord were excised and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Nerves were processed and sectioned by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Electron Microscopy Core. The tissue was treated with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through graded alcohols and embedded in Epon plastic. Cross sections were cut on a microtome at 1μm thick, mounted, and stained with toluidine blue. Axonal diameter was analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). At least 4 mice were analyzed per group.

Statistics

Student’s t test or ANOVA was used to test the significance of differences in mean values, and the null hypothesis was rejected at P < 0.05. Statistical tests on animal survival were performed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank test. Graphpad Prism or Microsoft Excel was used to compute statistical analysis.

Study Approval

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Massachusetts Medical School approved all animal experiments.

Results

AAV9 delivered amiRSOD1 targets cells of the CNS and decreases hSOD1 gene expression

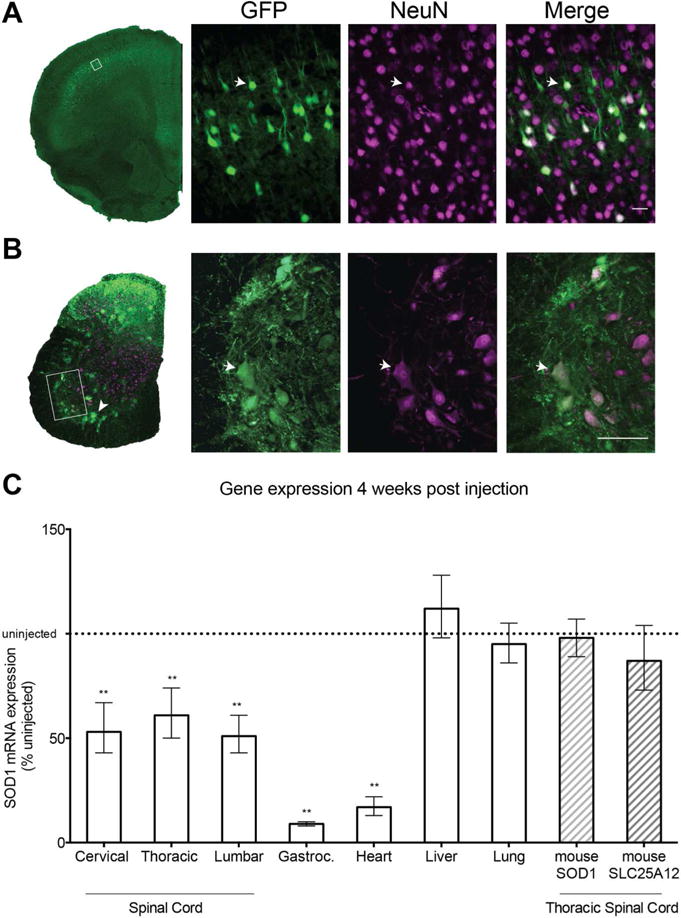

We first analyzed the CNS transduction profile of an AAV9-GFP vector delivered ICV in neonatal SOD1G93A mice at a total dose of 1×1011 vector genomes. Analysis of GFP expression at four weeks post-injection revealed transduced neurons in the motor cortex and ventral horn of the spinal cord (Fig 1, arrows). Based on location, size, and morphology, many of these GFP+ neurons are layer V cortical (Fig 1A) and spinal cord motor neurons (Fig 1B). It also appears that astrocytes or microglia were transduced in the spinal cord (Fig 1B, arrowhead), as gauged by the morphology of the cells and the lack of GFP/NeuN co-localization. This pattern of targeting (cortical and spinal motor neurons, glial cells) corresponds to the cell types most affected by ALS. We therefore investigated the therapeutic effectiveness of an AAV9 vector encoding an amiR against hSOD1 delivered ICV in neonatal SOD1G93A mice. We injected SOD1G93A mice at post-natal day 0–1 (P0-P1) and quantified hSOD1 mRNA levels at four weeks post injection (Fig 1C). Human SOD1 mRNA levels in spinal cord were reduced up to 50% with no significant difference between cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. In peripheral tissues, hSOD1 mRNA levels were reduced by more than 80% in heart and gastrocnemius muscle, but were unchanged in liver or lung. We also analyzed the levels of mouse SOD1 mRNA and found no changes in the thoracic spinal cord (Fig 1C). This was expected, since amiRSOD1 was designed to be human specific with four mismatches to the mouse SOD1 mRNA. To assess potential off-target effects of amiRSOD1 expression, we analyzed SLC25A12 mRNA levels in spinal cord as nucleotides 1 to 14 of the mature amiRSOD1 (ATGAACATGGAATC) are a perfect match to this mouse gene mRNA. Despite the high degree of homology, which includes the seed sequence of amiRSOD1 (nucleotides 2 to 8), there was no significant change in SLC25A12 mRNA levels in the spinal cord of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice compared to untreated controls (Fig 1C).

Figure 1. A single neonate ICV injection of AAV9 vectors transduces neurons in motor cortex and spinal cord, and reduces human SOD1 mRNA.

Immunofluorescence staining of brain (A) and spinal cord (B) sections with antibodies to GFP and NeuN revealed broad neuronal transduction. Boxes indicate locations of magnified regions. Arrows indicate double labeled cells. Arrowhead indicates non-neuronal transduced cells. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of gene expression. Human SOD1 mRNA was reduced by almost 50% at all three levels of the spinal cord, and more than 80% in the gastrocnemius and heart. No change was apparent in liver or lung. Endogenous mouse SOD1 and SLC25A12 mRNA levels were unchanged in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice. Dotted line indicates uninjected SOD1G93A mice. Scale bars, (A) 25μm, (B) 50μm. Data is represented as mean ± error; **p<0.005. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical comparison.

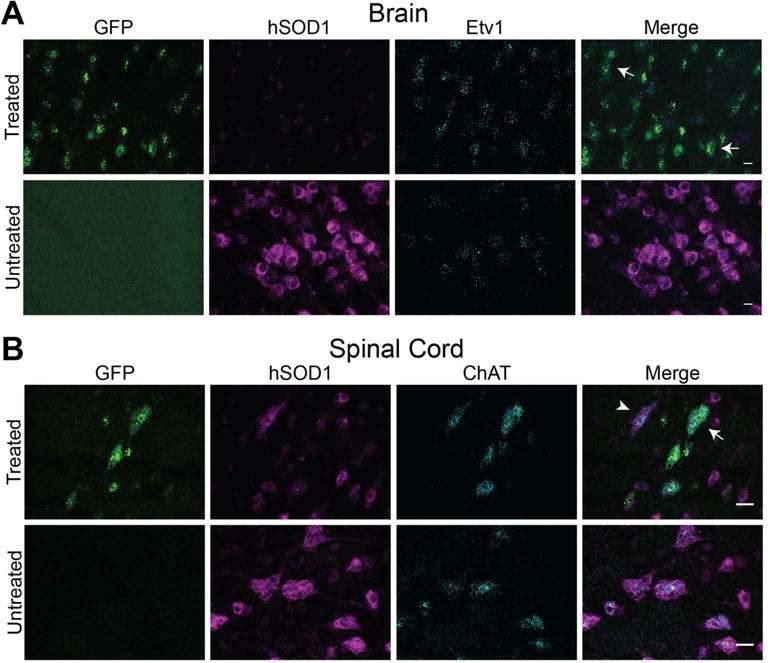

We also analyzed changes in hSOD1 mRNA levels in AAV9-transduced upper and lower motor neurons using multiplex fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNAscope). This technique provides detailed spatial information on changes in hSOD1 mRNA in specific cell populations such as spinal cord motor neurons and layer V upper motor neurons identified with probes specific for ChAT (choline acetyl transferase) or Etv1 (ets variant 1) (29), respectively (Fig 2). The intensity of hSOD1 mRNA signal was considerably reduced in cells expressing GFP mRNA both in motor cortex (Fig 2A) and spinal cord (Fig 2B). Furthermore, co-localization of GFP mRNA signal with probes specific for Etv1 and ChAT mRNAs confirms the transduction of both layer V cortical neurons (Fig 2A, arrows) and spinal cord motor neurons (Fig 2B, arrows) in AAV9-injected mice. Non-transduced ChAT-positive neurons (GFP-negative) show strong hSOD1 mRNA signal (Fig 2B, arrowhead).

Figure 2. SOD1 mRNA expression is reduced in AAV9-amiRSOD1 transduced cortical and spinal motor neurons.

Multiplex fluorescent in situ hybridization was used to assess changes in human SOD1 mRNA at the cellular level in the brain and spinal cord of AAV9-treated and untreated SOD1G93A mice at 4 weeks of age. Probes for GFP (green), and human SOD1 mRNA (magenta) were multiplexed with probes to genes in cortical (Etv1) or spinal cord (ChAT) motor neurons (cyan). Cells expressing GFP mRNA, indicating transduced cells, had reduced levels of hSOD1 mRNA, in both the brain (A) and spinal cord (B). Arrows indicate AAV9 transduced cells with reduced hSOD1 mRNA signal. Arrowhead indicates non-transduced cells, lacking GFP mRNA, and retaining high SOD1 mRNA signal in the spinal cord. Scale bars, (A) 10μm and (B) 25μm.

Neonatal treatment with AAV9-amiRSOD1 improves survival and delays the onset of paralysis in SOD1G93A mice

Based on the initial indications of efficient decrease of hSOD1 mRNA in upper and lower motor neurons we next assessed the therapeutic benefit of neonatal ICV injection of AAV9-amiRSOD1 vector in SOD1G93A mice. Litter matched SOD1G93A (n=22) and non-transgenic (NTG) control mice (n=12) were injected ICV with 1×1011 vg of AAV9-amiRSOD1. Control cohorts included untreated SOD1G93A (n=18) and NTG animals (n=12). A subset of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice were euthanized at 135 days (n=4) to assess disease status in these animals at the age corresponding to the median survival of untreated SOD1G93A mice. The remaining AAV9-treated SOD1G93A animals (n=18) were observed until the humane endpoint. NTG controls were also euthanized at 135 days (n=4), or at 260 days (n=8), past the age of the oldest surviving AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mouse.

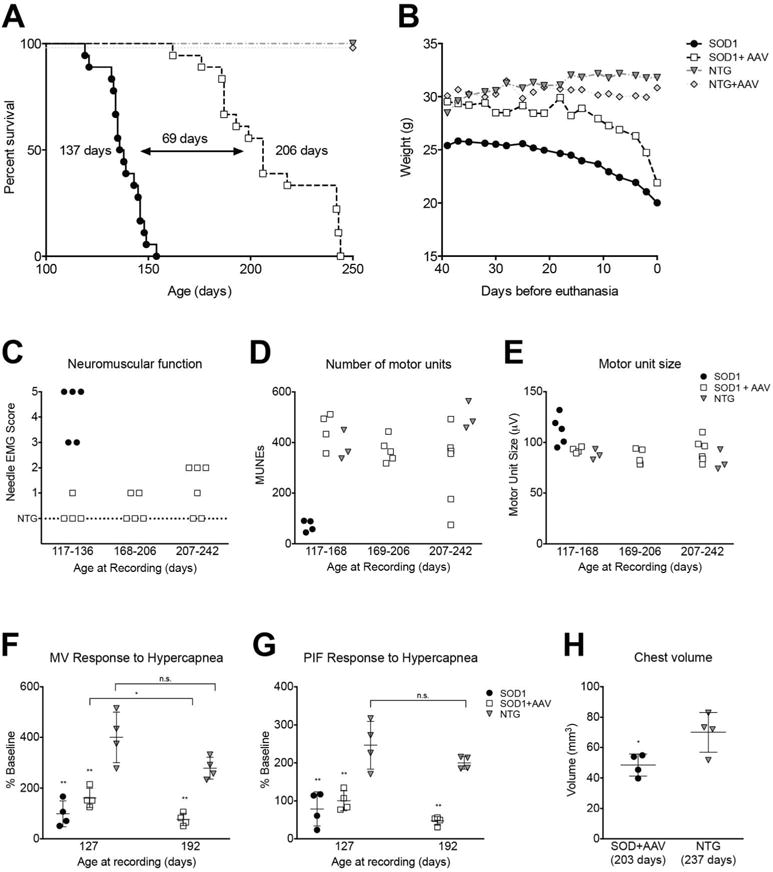

AAV9-amiRSOD1 treatment extended median survival by 50%, from 137 days for untreated SOD1G93A mice to 206 days (p<0.0001; Fig 3A). Untreated SOD1G93A mice develop hind limb paralysis (Movie S1A), but AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice do not show signs of paralysis or movement impairment (Movie S1B). Unexpectedly, AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice did not die from paralysis but instead were euthanized because of rapid weight loss (>15% body weight loss) and hunched appearance (Fig 3B). Even after weight loss the mice remained ambulatory and continued to display behaviors that require considerable limb strength, such as rearing and hanging from the wire food hopper (Movies S1C,D).

Figure 3. AAV9-amiRSOD1 treatment increases lifespan and improves neuromuscular function of SOD1G93A mice.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival plot shows a 69 day increase in median survival of AAV9-treated mice compared to untreated SOD1G93A littermates. Log-rank test, p<0.0001. (B) Average weights over the last 40 days before euthanasia show a sharp decline in the weight of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice, as compared to the steady decline in untreated SOD1G93A mice. Electrophysiological recordings revealed remarkable preservation of motor neuron function in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice as assessed by (C) needle electromyography scores, (D) number of motor units, and (E) motor unit size. Plethysmography recordings show a drop in response to hypercapnea in both (F) minute ventilation and (G) peak inspiratory flow in both AAV9-treated and untreated SOD1G93A mice, when compared to age matched NTG mice, indicating breathing impairment due to diaphragm dysfunction. Near the humane endpoint there is a significant decrease in (H) chest volume of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A compared to NTG mice. Each data point in (C–H) represents an individual animal. In (F–H) horizontal line and vertical bars represent mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical comparison. n.s., not significant.

In addition to observing the mice for limb paralysis, we also assessed neuromuscular function in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice and controls at different ages using quantitative electrophysiological measures (27, 30). Needle electromyography (EMG) assessed several critical muscle parameters including the presence of fibrillation potentials and the amplitude of the compound muscle action potential. The results were scored as 0 being normal to 5 being highly abnormal. The EMG scores of NTG control animals were zero while untreated SOD1G93A animals scored in the 3 to 5 range, corresponding to extensive acute muscle denervation (Fig 3C). In contrast, AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice scored 0 to 2 throughout the experiment. The scores of 2 were evident in only a subset of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice and only at older ages. Even at the latest time point analyzed (ranging from 207 to 242 days), some AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice had normal EMGs (scored zero).

We further assessed neuromuscular function by estimating the numbers and sizes of motor units (31). AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice maintained a normal number of motor units, and only a few mice, which had scored 2 on the EMG scale, showed a decrease at older ages (Fig 3D). We also quantified the motor unit size, which corresponds to the number of muscle fibers innervated; in ALS, this parameter can be a measure of axonal collateral re-innervation, which increases as motor neurons degenerate. Untreated SOD1G93A mice showed an increase in motor unit size compared to NTG controls while AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice maintained a normal motor unit size (Fig 3E). These quantitative measures of neuromuscular function were consistent with the absence of overt signs of paralysis in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice.

In ALS the most frequent cause of death is respiratory failure resulting from denervation of the diaphragm and the chest wall muscle. We therefore assessed pulmonary function on awake, spontaneously breathing animals. At 127 days, the AAV9-treated and untreated SOD1G93A mice had greater minute ventilation (MV) than NTG mice (p<0.05). However, when subjected to a respiratory challenge using hypercapnia both AAV9-treated and untreated SOD1G93A mice had a significantly attenuated MV response compared to NTG controls. By day 192, the AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice had a further decline in their MV response to the respiratory challenge compared to the day 127 recordings. Figure 3F,G illustrates the absolute change in MV (Fig 3F) and peak inspiratory flow (PIF) (Fig 3G) during hypercapnia relative to baseline in each group. PIF is reflective of diaphragm strength; progressive diaphragm weakness seems likely in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice since PIF values declined with age. Additionally, chest CT scans of >200 day old animals showed decreased chest volume in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice compared to NTG controls (Fig 3H).

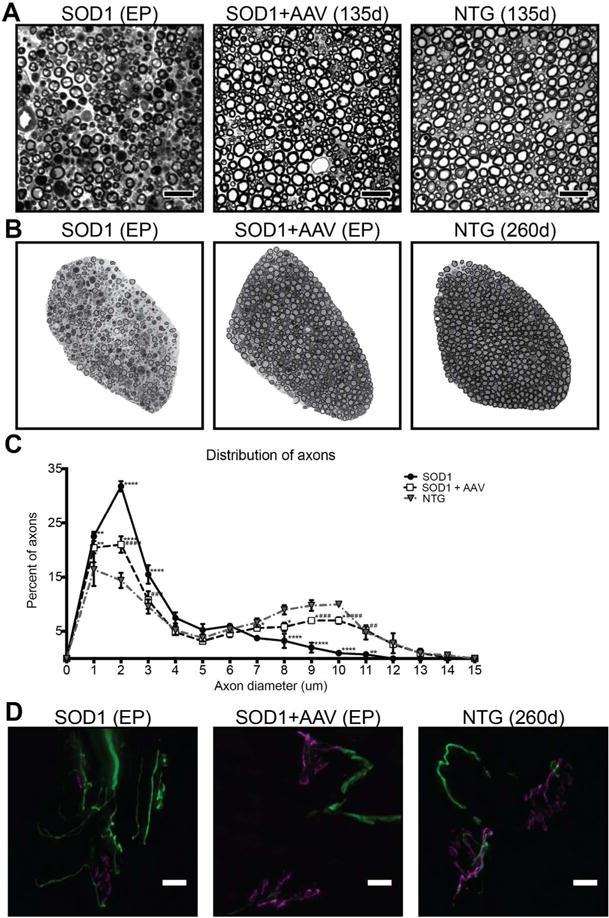

AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice have improved axonal integrity and motor neuron numbers

Next we evaluated axonal integrity in sciatic nerve and ventral roots of the lumbar spinal cord as gauged by the distribution of fiber sizes. On comparing the sciatic nerves of end-stage untreated SOD1G93A mice, AAV9-treated SOD1G93A and NTG mice at 135 days of age, we observed extensive axonal loss in untreated SOD1G93A mice, while the sciatic nerves of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A and NTG mice were indistinguishable (Fig 4A). We also analyzed lumbar ventral roots, which are composed solely of motor axons; it is well documented that the large caliber alpha axons degenerate in the ventral roots of ALS patients and SOD1G93A mice (32–35). We observed this degeneration in untreated SOD1G93A mice when compared to NTG mice as denoted by a shift in axonal size distribution towards small caliber axons (Fig 4B,C). The distribution of ventral root axon size in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at endpoint is between that in untreated SOD1G93A and NTG mice. The numbers of large and small diameter fibers in the ventral roots of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice is significantly different from untreated SOD1G93A mice and NTG controls (Fig 4C). Thus, AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice display remarkable preservation of axonal integrity. ALS has been described as a dying back neuropathy, a term that implies greater distal than proximal peripheral nerve degeneration. We therefore also assessed the integrity of neuromuscular junctions (NMJ) in all cohorts. AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at the humane endpoint revealed variable degrees of mild NMJ denervation, and overall distinctly less disorganization than detected in untreated SOD1G93A mice (Fig 4D).

Figure 4. AAV9-amiRSOD1 treatment preserves axons in sciatic nerve and lumbar ventral roots, and neuromuscular junctions.

(A) Cross sections of sciatic nerves of untreated SOD1G93A mice at endpoint were compared with AAV9-treated SOD1G93A, and NTG mice at 135 days. Representative toluidine blue stained sections showed degeneration only in untreated SOD1G93A mice. (B) Ventral roots of untreated SOD1G93A mice were compared with AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at their respective endpoints, and NTG mice at 260 days. Representative toluidine blue stained sections are shown for all three cohorts. (C) Quantitative analysis of ventral root axon fiber distribution in SOD1G93A mice showed loss of large diameter fibers with a shift toward small diameter fibers compared to NTG mice. AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice displayed a fiber distribution pattern between untreated NTG and SOD1G93A mice. (D) NMJs were analyzed in untreated and AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at their respective endpoints and in NTG mice at 260 days. Immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against neurofilament-200 (green) and α–bungarotoxin (magenta) revealed disorganized neuromuscular junctions in untreated SOD1G93A at endpoint. AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice had variable degrees of NMJ denervation, depending on the animal and NMJ analyzed. Scale bar, (A) 25μm, (D) 50μm. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. *,# p<0.05, **, ## p<0.01, ***, ### <0.005, ****, #### p<0.001. All animals were compare to compared to NTG mice (*), AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice were compared to untreated SOD1G93A mice (#). Dunnett’s multiple comparison test after two way ANOVA was used for statistical comparison.

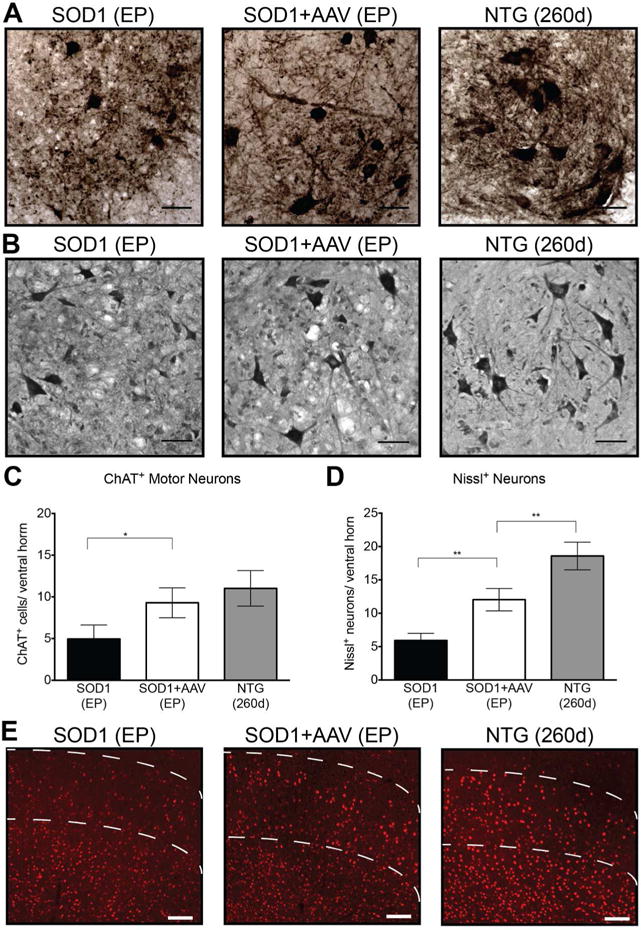

We also quantified the number of motor neurons in the ventral horn of lumbar spinal cord at endpoint by counting ChAT+ neurons. The end stage spinal cords of untreated SOD1G93A mice had a significant reduction in the number of ChAT+ neurons compared to control NTG mice (Fig 5A,C). In contrast, there was no statistical difference between end stage AAV9-treated SOD1G93A and NTG mice (Fig 5C). To account for the possibility that we were including ChAT+ neurons compromised by the disease we also quantified numbers of motor neurons using a Nissl stain (Fig 5B). Stained cells in the ventral horn with a cell body area >250μm2 were considered motor neurons (28). This method also showed a significantly higher number of motor neurons in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice compared to untreated SOD1G93A mice, albeit lower than in control NTG mice (Fig 5B,D). This confirms that our AAV treatment dramatically preserved motor neurons.

Figure 5. AAV9-amiRSOD1 treatment improves survival of spinal cord and corticospinal motor neurons.

Untreated SOD1G93A mice were compared with AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at their respective endpoints, and NTG mice at 260 days. Immunostaining for ChAT positive motor neurons (A) and Nissl-positive neurons (B) of the lumbar spinal cord showed significant preservation of motor neurons in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice when compared to untreated SOD1G93A mice. Motor neurons were quantified, defined as either ChAT-positive cells (C) or Nissl-positive cells larger than 250μm2 (D), in the ventral horn of the lumbar spinal cord. (E) Immunostaining for Ctip positive neurons of motor cortex showed preservation of neurons in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice when compared to untreated mice. Dotted lines represent region of layer V neurons. Scale bar, (A,B) 50 μm (E) 100μm. Data is represented as mean ± standard deviation. *p<0.005, **p<0.001. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical comparison.

Recently it has been shown that upper motor neurons undergo degeneration in SOD1G93A mice (36) as seen in human ALS. Therefore we analyzed the motor cortex of mice in all three cohorts for the presence of layer V motor neurons identified by immunofluorescence staining with a Ctip2-specific antibody (36, 37). A qualitative assessment suggests that there are lower numbers of neurons in the untreated SOD1G93A mice at endpoint compared to NTG mice, and that AAV9 treatment had a modest impact on survival of cortical layer V motor neurons. Thus, although a large number of cortical neurons were transduced, it was not sufficient to fully protect the whole layer V neuronal population (Fig 5E).

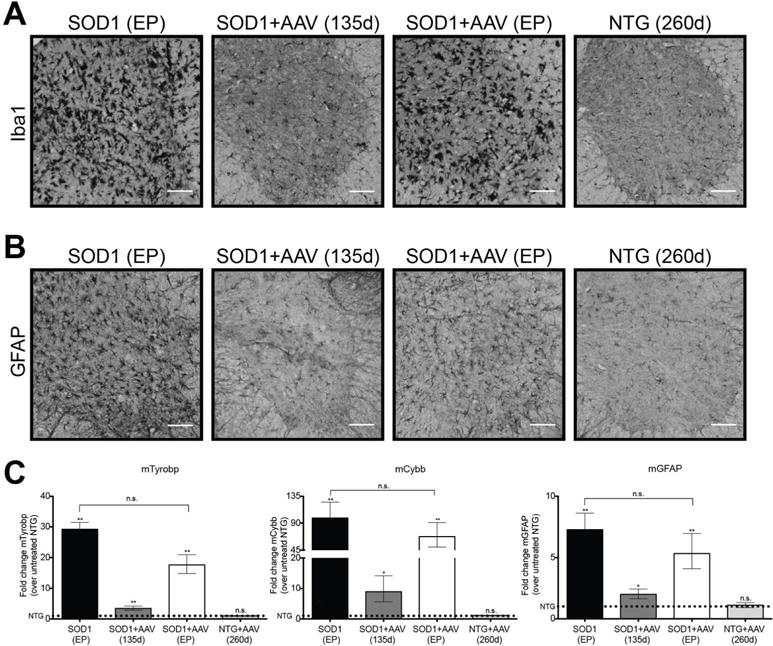

AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice show delayed onset of inflammation in the spinal cord

Motor neuron death in both human and mouse ALS is accompanied by a neuroinflammatory process characterized by activation of astrocytes and microglia. We assessed the levels of inflammatory markers in the lumbar spinal cord of our ALS mouse cohorts. The AAV9-mediated silencing of hSOD1 in the SOD1G93A mice markedly delayed the onset of microgliosis and astrocytosis (Fig 6). The spinal cord of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at 135 days of age showed a marginal increase in activated Iba1+ microglia (Fig 6A) and GFAP+ reactive astrocytes (Fig 6B) compared to NTG control animals at 260 days. A considerable increase in these markers was apparent by the humane endpoint (median age 206 days) of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice, but perhaps to a lower extent than observed in untreated SOD1G93A mice at their humane endpoint. To validate these observations using a quantitative assay, we performed RT-qPCR for genes up-regulated in activated microglia (Tyrobp, Cybb) (38) and reactive astrocytes (GFAP) (39). All three genes were significantly increased in the spinal cord of untreated SOD1G93A mice and to a lesser extent in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A animals at 135 days of age, but reached comparable levels by the humane endpoint. The expression levels of these three genes were unchanged by AAV9 treatment of NTG animals.

Figure 6. AAV9-amiRSOD1 treatment delays the onset of spinal cord inflammation in SOD1G93A mice.

The presence of inflammatory markers in the spinal cord of AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at 135 days and humane endpoint was compared to that in untreated SOD1G93A also at their humane endpoint, and NTG mice at 260 days of age. Immunohistochemistry for Iba1, a marker for activated microglia, (A) and for GFAP, a marker for astrogliosis (B), showed mild changes in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice at 135 days but a strong increase in these histological markers at the humane endpoint. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of genes up-regulated in activated microglia (Tyrobp, Cybb) and reactive astrocytes (GFAP) confirmed the histological findings. Statistical comparisons were made to age matched untreated NTG mice (dotted line), or to untreated SOD1G93A mice as shown with brackets. Scale bar, (A,B) 100μm. Data is represented as the mean ± error. *p<0.05, **p<0.005. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used for statistical comparison. n.s., not significant.

Discussion

In this study, we have explored gene silencing as a therapy for the SOD1G93A transgenic ALS mouse model. Using an AAV9-amiRSOD1 vector delivered ICV neonatally, we achieved a 50% increase in median survival, as well as a remarkable preservation of motor function. Surprisingly the end-stage for these animals was due to rapid weight loss and severe kyphosis, rather than limb paralysis. Even at end-stage, AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice retained the ability to rear and hang from the metal grates in the cage. The histological outcome measures in this study document that AAV9 treatment delayed but did not arrest disease progression.

The best improvements in lifespan in this ALS mouse model using a viral vector delivered shRNA against SOD1 were achieved with multiple intramuscular injections in P7 mice with a lentivirus vector (77% prolongation) (15) or a systemic injection in P0 mice with an AAV9 vector (39% prolongation) (40). To our knowledge the survival benefit we report here using AAV9 to deliver an artificial microRNA directed against hSOD1 is the largest yet achieved with any AAV gene therapy in SOD1G93A mice or rats.

The most common cause of death in ALS patients is respiratory failure, reflecting weakness of both the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles. This impaired breathing was also documented here in SOD1G93A mice. Physiological measurements of breathing during a respiratory challenge with hypercapnea revealed a significant decrease in minute ventilation in AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice compared to NTG mice, which continued to decline with age. The decreased response to the hypercapnic challenge is indicative of respiratory impairment, and implies an increase in breathing effort at rest, as is commonly seen in restrictive pulmonary disease of neuromuscular origin. Furthermore, the kyphotic posture of the AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice near the time of euthanasia is consistent with intercostal muscle and diaphragm weakness resulting in a smaller chest volume. This restriction of lung inflation further contributes to breathing impairment. In addition, the peak inspiratory force during the respiratory challenge, an indirect measure of diaphragm function, was significantly reduced compared to non-transgenic mice. Thus, our AAV9-treated mice display a respiratory phenotype at endpoint that is similar to the restrictive lung disease of ALS patients, and could potentially be the cause of death.

In our study, the rapid weight loss and severe kyphosis in the last days before AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice were euthanized was surprising, as the animals are typically euthanized due to paralysis, yet in our study they remained fully active and ambulatory. The electrophysiological parameters for most AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice remained largely within normal range until end-stage, at which point a few animals showed some evidence of hind limb weakness. These data combined with our analysis of spinal cord inflammatory markers and motor neuron counts indicate that AAV9 treatment delayed but did not prevent disease progression. It is conceivable that the greatly delayed but persistent disease process reflects the residual level of mutant hSOD1 expression in brain and spinal motor neurons. It is also likely a consequence of unabated hSOD1 expression in non-neuronal cells. Several studies document that expression of this protein in non-neuronal cells, such as microglia, astrocytes and oligodendroglia is sufficient to drive disease progression in the absence of neuronal expression (7, 41–43). As our treatment is in a neonatal setting, the non-integrating vector genomes are diluted over time in proliferating cells during post-natal development. This is seen with the liver and lung of our AAV9-treated mice, where we found no evidence of hSOD1 silencing, despite AAV9 tropism to these organs. Thus, it is likely that non-neuronal cells also lost expression of our amiRSOD1 during post-natal brain development, diminishing the efficacy of hSOD1 silencing in these cell types.

The therapeutic efficiency reported here might be a result of silencing hSOD1 expression in both cortical and spinal motor neurons. Silencing in both types of motor neurons was indicated by the in situ hybridization analysis of hSOD1 mRNA in these neuronal populations. Two recent publications suggest that simultaneous silencing of hSOD1 in both motoneuron populations is likely necessary to achieve the best survival outcomes. Foust et al showed that vascular administration of AAV9-shRNA vector in neonatal (P0) SOD1G93A mice was effective at silencing hSOD1 expression in the spinal cord and extended survival by 51.5 days, but mice still succumbed to hind limb paralysis. AAV9 vectors delivered systemically in neonatal mice are exceptionally efficient for gene transfer to spinal cord transducing a large percentage of neurons and glia. However the majority of transduced cells in the cerebral cortex are glia and endothelial cells (18, 44). Thus, a systemic neonate delivery of AAV9-shRNA is unlikely to have a major impact on hSOD1 expression in corticospinal motor neurons. Thomsen et al. showed that hSOD1 silencing selectively in cortical but not spinal motor neurons with an AAV9-shRNA vector extends survival of SOD1 rats by ~20 days (45), demonstrating that the status of the cortical motor neurons is a critical determinant of survival in this model. It is apparent from these articles that treatment of either population of motor neurons alone is beneficial, but not sufficient to substantially change the course of disease progression. By contrast, the ICV delivery route explored in our studies achieves efficient gene delivery to both corticospinal and spinal cord motor neurons; this is the likely basis for the robust and persisting improvement in motor function in our AAV9-treated mice. In addition to silencing of hSOD1 in CNS, it is likely that reduction of hSOD1 in skeletal muscle by >80% also contributed to the therapeutic effect since muscle-specific expression of mutant SOD1 triggers motor neuron loss in the spinal cord (46). However, it is unlikely that hSOD1 silencing in skeletal muscle is the distinguishing factor of our AAV gene therapy, since a systemic AAV9 infusion, such as that tested by Foust et al, would also reduce hSOD1 in the skeletal muscle (40).

A recent study showed that neonatal ICV infusion of AAV vectors encoding an amiR-SOD1 under the CMV or GFAP promoters extended survival of B6 SOD1G93A mice by 26% and 14%, respectively (47); the combined injection of both AAV vectors did not provide additional benefit. Moreover, while none of the mice in that study developed hind limb paralysis (they succumbed to infections and gastrointestinal complications), the survival outcomes were less robust than ours (50%). This is particularly striking because SOD1G93A mice in the B6/SJL background have a more severe phenotype than in a pure B6 background with median survivals of 129 and 167 days, respectively (48). Several design features in our single-stranded AAV9 vector may account for its efficacy such as the CBA promoter, our amiRSOD1 design or the WPRE element in the vector-derived mRNA. Presently we have no indication on which of these elements may be responsible for the superior therapeutic efficacy of our AAV9-amiRSOD1 vector.

The widespread gene delivery afforded by neonatal ICV delivery of AAV9-amiRSOD1 vector provides insight into therapeutic outcomes that may be achievable in adults. If a CNS transduction profile similar to that in neonates can be replicated in adults, we anticipate the therapeutic outcomes to be superior to those achieved by neonatal intervention. We specifically expect this, as in the adult brain fewer vector genomes will be lost in microglia and astrocytes due to cell division. This would result in sustained silencing of hSOD1 expression in these populations, and thus suppression, either partial or complete, of non-cell autonomous effects in disease progression. Large animal studies have already shown the ability of AAV9 to transduce the CNS using alternative delivery approaches, such as cisterna magna (49) and intrathecal infusions (50). Our particular amiR is not specific to any one mutant allele and thus can be used for all patients with an SOD1 mutation. Although it will reduce the levels of both wild type and mutant alleles it is unlikely that reduction of overall levels of SOD1 will be detrimental to patients, since SOD1 knock out mice to do not display any overt toxicities (51), and a phase I study using non-allele specific antisense oligonucleotides for ALS has proven safe (52). However, a potential consideration is the co-delivery of an amiR-resistant SOD1 to counteract any potential effects of excessive SOD1 reduction. Additionally, recent studies have show it is possible to design allele specific amiRs using single nucleotide differences between mutant and wild type alleles (53). As AAV delivery to the CNS has shown consistent safety in multiple clinical trials (54–56), our approach using an AAV mediated CSF delivery of a therapeutic artificial microRNA for SOD1 is directly translatable to the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1. AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice do not die from paralysis.

Movie S1A: Untreated SOD1G93A mouse at 135 days shows signs of hind limb paralysis.

Movies S1C, S1D: AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mouse at its humane endpoint (>200 days) is thin and has signs of kyphosis, but is still able to climb and hang from a metal food hopper.

Movie S1B: AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mouse at 198 days does not show signs of paralysis, or any movement impairment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Terence Flotte for intellectual contributions, as well as Dr. Owen Peters and Dr. Eric Danielson for technical support with nerve isolation, NMJ and ChAT staining, Kaitlin Wetmore for performing the plethysmography recordings, Lina Song for the original cloning of the amiRSOD1 sequence, and Stacy Maitland for producing the AAV vector. We would also like to acknowledge the UMMS electron microscopy core for performing nerve embedding, cutting and staining, and the UMMS small animal imaging core for performing all CT imaging.

We thank NINDS (NS088689 to CM and RHB, and NS079836 to RHB), the NICHD (HD077040 to MKE), the Parker B. Francis Fellowship (MKE), the ALS Therapy Alliance, the ALS Association, the Angel Fund, the Al-Athel Foundation, the Pierre L. de Bourgknecht ALS Research Foundation, Project ALS, P2ALS and ALS Finding A Cure (RHB).

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: CM has filed a patent for the artificial microRNA used in this publication, provisional application number 61/955, 189. RHB is a founder of AviTx, Inc., a virtual company that supports ALS research.

Author contributions

LS, MKE, CM, RHB and MSE contributed to study concept and design.

LS, SHT, GTC, JS, MKE, CM, RHB and MSE contributed to data acquisition and analysis.

LS, MKE, RHB and MSE contributed to drafting the text and figures.

References

- 1.Renton AE, Chio A, Traynor BJ. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17(1):17–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O’Regan JP, Deng HX, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362(6415):59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferraiuolo L, Higginbottom A, Heath PR, Barber S, Greenald D, Kirby J, Shaw PJ. Dysregulation of astrocyte-motoneuron cross-talk in mutant superoxide dismutase 1-related amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2011;134(Pt 9):2627–41. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foran E, Trotti D. Glutamate transporters and the excitotoxic path to motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2009;11(7):1587–602. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robberecht W, Philips T. The changing scene of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14(4):248–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haidet-Phillips AM, Hester ME, Miranda CJ, Meyer K, Braun L, Frakes A, Song S, Likhite S, Murtha MJ, Foust KD, et al. Astrocytes from familial and sporadic ALS patients are toxic to motor neurons. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29(9):824–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papadeas ST, Kraig SE, O’Banion C, Lepore AC, Maragakis NJ. Astrocytes carrying the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1G93A) mutation induce wild-type motor neuron degeneration in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(43):17803–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103141108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frakes AE, Ferraiuolo L, Haidet-Phillips AM, Schmelzer L, Braun L, Miranda CJ, Ladner KJ, Bevan AK, Foust KD, Godbout JP, et al. Microglia induce motor neuron death via the classical NF-kappaB pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuron. 2014;81(5):1009–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264(5166):1772–5. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarrott JM, Herranz-Martin S, Alrafiah AR, Shaw PJ, Azzouz M. Current developments in gene therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2015:1–13. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1044894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Yang B, Qiu L, Yang C, Kramer J, Su Q, Guo Y, Brown RH, Jr, Gao G, Xu Z. Widespread spinal cord transduction by intrathecal injection of rAAV delivers efficacious RNAi therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23(3):668–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel P, Kriz J, Gravel M, Soucy G, Bareil C, Gravel C, Julien JP. Adeno-associated virus-mediated delivery of a recombinant single-chain antibody against misfolded superoxide dismutase for treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2014;22(3):498–510. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RA, Miller TM, Yamanaka K, Monia BP, Condon TP, Hung G, Lobsiger CS, Ward CM, McAlonis-Downes M, Wei H, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for neurodegenerative disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116(8):2290–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI25424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Ghosh A, Baigude H, Yang CS, Qiu L, Xia X, Zhou H, Rana TM, Xu Z. Therapeutic gene silencing delivered by a chemically modified small interfering RNA against mutant SOD1 slows amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(23):15845–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800834200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ralph GS, Radcliffe PA, Day DM, Carthy JM, Leroux MA, Lee DC, Wong LF, Bilsland LG, Greensmith L, Kingsman SM, et al. Silencing mutant SOD1 using RNAi protects against neurodegeneration and extends survival in an ALS model. Nature medicine. 2005;11(4):429–33. doi: 10.1038/nm1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broekman ML, Comer LA, Hyman BT, Sena-Esteves M. Adeno-associated virus vectors serotyped with AAV8 capsid are more efficient than AAV-1 or -2 serotypes for widespread gene delivery to the neonatal mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2006;138(2):501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean JR, Smith GA, Rocha EM, Hayes MA, Beagan JA, Hallett PJ, Isacson O. Widespread neuron-specific transgene expression in brain and spinal cord following synapsin promoter-driven AAV9 neonatal intracerebroventricular injection. Neuroscience letters. 2014;576:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nature biotechnology. 2009;27(1):59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Li S, Wang H, Guo Y, Gessler DJ, Cao C, Su Q, Kramer J, Zhong L, Ahmed SS, et al. Global CNS transduction of adult mice by intravenously delivered rAAVrh.8 and rAAVrh.10 and nonhuman primates by rAAVrh.10. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2014;22(7):1299–309. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsberg K, Andersen PM, Marklund SL, Brannstrom T. Glial nuclear aggregates of superoxide dismutase-1 are regularly present in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta neuropathologica. 2011;121(5):623–34. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0805-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borel F, Gernoux G, Cardozo B, Metterville JP, Toro Cabreja GC, Song L, Su Q, Gao GP, Elmallah MK, Brown RH, Jr, et al. Therapeutic rAAVrh10 Mediated SOD1 Silencing in Adult SOD1(G93A) Mice and Nonhuman Primates. Human gene therapy. 2016;27(1):19–31. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zolotukhin S, Byrne BJ, Mason E, Zolotukhin I, Potter M, Chesnut K, Summerford C, Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene therapy. 1999;6(6):973–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timaru-Kast R, Herbig EL, Luh C, Engelhard K, Thal SC. Influence of Age on Cerebral Housekeeping Gene Expression for Normalization of Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction after Acute Brain Injury in Mice. Journal of neurotrauma. 2015;32(22):1777–88. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jara JH, Genc B, Cox GA, Bohn MC, Roos RP, Macklis JD, Ulupinar E, Ozdinler PH. Corticospinal Motor Neurons Are Susceptible to Increased ER Stress and Display Profound Degeneration in the Absence of UCHL1 Function. Cerebral cortex. 2015 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia RH, Yosef N, Ubogu EE. Dorsal caudal tail and sciatic motor nerve conduction studies in adult mice: technical aspects and normative data. Muscle & nerve. 2010;41(6):850–6. doi: 10.1002/mus.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miana-Mena FJ, Munoz MJ, Yague G, Mendez M, Moreno M, Ciriza J, Zaragoza P, Osta R. Optimal methods to characterize the G93A mouse model of ALS. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other motor neuron disorders : official publication of the World Federation of Neurology, Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. 2005;6(1):55–62. doi: 10.1080/14660820510026162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Hoecke A, Schoonaert L, Lemmens R, Timmers M, Staats KA, Laird AS, Peeters E, Philips T, Goris A, Dubois B, et al. EPHA4 is a disease modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in animal models and in humans. Nature medicine. 2012;18(9):1418–22. doi: 10.1038/nm.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groh A, Meyer HS, Schmidt EF, Heintz N, Sakmann B, Krieger P. Cell-type specific properties of pyramidal neurons in neocortex underlying a layout that is modifiable depending on the cortical area. Cerebral cortex. 2010;20(4):826–36. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shefner JM, Reaume AG, Flood DG, Scott RW, Kowall NW, Ferrante RJ, Siwek DF, Upton-Rice M, Brown RH., Jr Mice lacking cytosolic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase display a distinctive motor axonopathy. Neurology. 1999;53(6):1239–46. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shefner JM, Cudkowicz M, Brown RH., Jr Motor unit number estimation predicts disease onset and survival in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle & nerve. 2006;34(5):603–7. doi: 10.1002/mus.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer LR, Culver DG, Tennant P, Davis AA, Wang M, Castellano-Sanchez A, Khan J, Polak MA, Glass JD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: evidence in mice and man. Experimental neurology. 2004;185(2):232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo YS, Wu DX, Wu HR, Wu SY, Yang C, Li B, Bu H, Zhang YS, Li CY. Sensory involvement in the SOD1-G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2009;41(3):140–50. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.3.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen MD, Lariviere RC, Julien JP. Reduction of axonal caliber does not alleviate motor neuron disease caused by mutant superoxide dismutase 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(22):12306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seijffers R, Zhang J, Matthews JC, Chen A, Tamrazian E, Babaniyi O, Selig M, Hynynen M, Woolf CJ, Brown RH., Jr ATF3 expression improves motor function in the ALS mouse model by promoting motor neuron survival and retaining muscle innervation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(4):1622–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozdinler PH, Benn S, Yamamoto TH, Guzel M, Brown RH, Jr, Macklis JD. Corticospinal motor neurons and related subcerebral projection neurons undergo early and specific neurodegeneration in hSOD1G(9)(3)A transgenic ALS mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(11):4166–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arlotta P, Molyneaux BJ, Chen J, Inoue J, Kominami R, Macklis JD. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45(2):207–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu IM, Morimoto ET, Goodarzi H, Liao JT, O’Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, Muratet M, Carroll MC, Levy S, Tavazoie S, et al. A neurodegeneration-specific gene-expression signature of acutely isolated microglia from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Cell reports. 2013;4(2):385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vargas MR, Johnson JA. Astrogliosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: role and therapeutic potential of astrocytes. Neurotherapeutics: the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2010;7(4):471–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foust KD, Salazar DL, Likhite S, Ferraiuolo L, Ditsworth D, Ilieva H, Meyer K, Schmelzer L, Braun L, Cleveland DW, et al. Therapeutic AAV9-mediated suppression of mutant SOD1 slows disease progression and extends survival in models of inherited ALS. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2013;21(12):2148–59. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, Chalazonitis A, Jessell TM, Wichterle H, Przedborski S. Astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutated SOD1 release factors selectively toxic to motor neurons. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10(5):615–22. doi: 10.1038/nn1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang SH, Li Y, Fukaya M, Lorenzini I, Cleveland DW, Ostrow LW, Rothstein JD, Bergles DE. Degeneration and impaired regeneration of gray matter oligodendrocytes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16(5):571–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lobsiger CS, Cleveland DW. Glial cells as intrinsic components of non-cell- autonomous neurodegenerative disease. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10(11):1355–60. doi: 10.1038/nn1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Yang B, Mu X, Ahmed SS, Su Q, He R, Wang H, Mueller C, Sena-Esteves M, Brown R, et al. Several rAAV vectors efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier and transduce neurons and astrocytes in the neonatal mouse central nervous system. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19(8):1440–8. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomsen GM, Gowing G, Latter J, Chen M, Vit JP, Staggenborg K, Avalos P, Alkaslasi M, Ferraiuolo L, Likhite S, et al. Delayed disease onset and extended survival in the SOD1G93A rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis after suppression of mutant SOD1 in the motor cortex. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34(47):15587–600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2037-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong M, Martin LJ. Skeletal muscle-restricted expression of human SOD1 causes motor neuron degeneration in transgenic mice. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19(11):2284–302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dirren E, Aebischer J, Rochat C, Towne C, Schneider BL, Aebischer P. SOD1 silencing in motoneurons or glia rescues neuromuscular function in ALS mice. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2015;2(2):167–84. doi: 10.1002/acn3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heiman-Patterson TD, Sher RB, Blankenhorn EA, Alexander G, Deitch JS, Kunst CB, Maragakis N, Cox G. Effect of genetic background on phenotype variability in transgenic mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a window of opportunity in the search for genetic modifiers. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: official publication of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. 2011;12(2):79–86. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.550626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samaranch L, Salegio EA, San Sebastian W, Kells AP, Bringas JR, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS. Strong cortical and spinal cord transduction after AAV7 and AAV9 delivery into the cerebrospinal fluid of nonhuman primates. Human gene therapy. 2013;24(5):526–32. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer K, Ferraiuolo L, Schmelzer L, Braun L, McGovern V, Likhite S, Michels O, Govoni A, Fitzgerald J, Morales P, et al. Improving single injection CSF delivery of AAV9-mediated gene therapy for SMA: a dose-response study in mice and nonhuman primates. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2015;23(3):477–87. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reaume AG, Elliott JL, Hoffman EK, Kowall NW, Ferrante RJ, Siwek DF, Wilcox HM, Flood DG, Beal MF, Brown RH, Jr, et al. Motor neurons in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient mice develop normally but exhibit enhanced cell death after axonal injury. Nature genetics. 1996;13(1):43–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller TM, Pestronk A, David W, Rothstein J, Simpson E, Appel SH, Andres PL, Mahoney K, Allred P, Alexander K, et al. An antisense oligonucleotide against SOD1 delivered intrathecally for patients with SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase 1, randomised, first-in-man study. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(5):435–42. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monteys AM, Wilson MJ, Boudreau RL, Spengler RM, Davidson BL. Artificial miRNAs Targeting Mutant Huntingtin Show Preferential Silencing In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecular therapy Nucleic acids. 2015;4:e234. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bartus RT, Baumann TL, Siffert J, Herzog CD, Alterman R, Boulis N, Turner DA, Stacy M, Lang AE, Lozano AM, et al. Safety/feasibility of targeting the substantia nigra with AAV2-neurturin in Parkinson patients. Neurology. 2013;80(18):1698–701. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182904faa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandel RJ. CERE-110, an adeno-associated virus-based gene delivery vector expressing human nerve growth factor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Current opinion in molecular therapeutics. 2010;12(2):240–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tardieu M, Zerah M, Husson B, de Bournonville S, Deiva K, Adamsbaum C, Vincent F, Hocquemiller M, Broissand C, Furlan V, et al. Intracerebral administration of adeno-associated viral vector serotype rh.10 carrying human SGSH and SUMF1 cDNAs in children with mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA disease: results of a phase I/II trial. Human gene therapy. 2014;25(6):506–16. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie S1. AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mice do not die from paralysis.

Movie S1A: Untreated SOD1G93A mouse at 135 days shows signs of hind limb paralysis.

Movies S1C, S1D: AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mouse at its humane endpoint (>200 days) is thin and has signs of kyphosis, but is still able to climb and hang from a metal food hopper.

Movie S1B: AAV9-treated SOD1G93A mouse at 198 days does not show signs of paralysis, or any movement impairment.