Abstract

Objective. To assess the development of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors for collaborative practice among first-year pharmacy students following completion of interprofessional education.

Methods. A mixed-methods strategy was employed to detect student self-reported change in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Validated survey tools were used to assess student perception and attitudes. The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was used to capture student reflections and provide peer discussion on the individual IPE sessions.

Results. The validated survey tools did not detect any change in students’ attitudes and perceptions. The NGT succeeded in providing a milieu for participating students to reflect on their IPE experiences. The peer review process allowed students to compare their initial perceptions and reactions and renew their reflections on the learning experience.

Conclusion. The NGT process has provided the opportunity to assess the student experience through the reflective process that was enriched via peer discussion. Students have demonstrated more positive attitudes and behaviors toward interprofessional working through IPE.

Keywords: pharmacy education, interprofessional education, reflective practice, nominal group technique

INTRODUCTION

Enhanced coordination of health care practitioners through interdisciplinary collaboration benefits patients by preventing fragmentation of care.1,2 Interprofessional teams improve the quality of patient care,3,4 with lower costs4,5 and decreased length of hospital stay.6 Interprofessional education (IPE), defined as “education expressly intended to promote the effective function of a health team involving the relevant health professions,”7,8 has received much focus globally as a means to achieve this collaborative practice. The Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) describes IPE as “occasions when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and quality of care.”9

Interprofessional education can take many guises, some of which may not be as effective as others in cultivating collaborative practice.10 Certain fundamental conditions have been claimed to be crucial for the success of IPE in achieving positive attitude change at the undergraduate level. The “contact hypothesis” outlines prerequisites of a physically and emotionally comfortable learning environment, such as ensuring that the setting and participants are positive and cooperative; there is institutional support and collaboration; members of the group are representative (eg, of a profession or social group), and of equal status and there should be positive feedback to students.11

In the development and evaluation of IPE initiatives, there are two learning theories that can be applied, namely the behaviorist and constructivist approaches. Hean and colleagues delineate how behaviorists focus more on the outcomes of learning expressed as behaviors.12 This theory has been largely excluded from literature describing IPE curriculum design.12 However, the Kirkpatrick model13 of evaluation of learning outcomes adapted by Barr and colleagues14 (Table 1), which is behaviorist in approach, has been used to measure the effectiveness of IPE programs.15,16

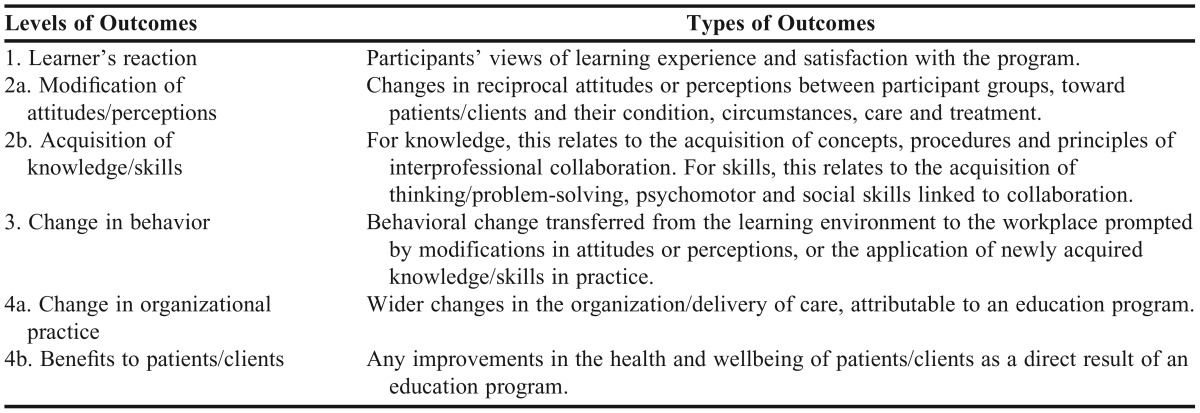

Table 1.

Classification of Interprofessional Outcomes as Designed by Kirkpatrick/Barr13,14

The measurement of change in student behavior within interprofessional working (level 3 in Table 1) is an example of a behaviorist approach to evaluation. This has traditionally been hard to identify and measure especially at the undergraduate stage12 except through the method of self-reporting by the student.15,17 More advanced levels of this outcome framework such as change in organizational practice (level 4a) and benefits to patients (level 4b) are problematic to use in measuring prequalification and require longitudinal evaluation.18 Constructivists focus on the process of learning or constructing knowledge and encompass a range of theories under two categories: cognitive and social constructivism. Hean and colleagues highlight that the use of various theories within currently published IPE literature has created an “un-navigable quagmire” and recommend that future researchers apply theories to soundly and robustly underpin practice, both in the design of IPE within curricula and in its subsequent evaluation.12 Other researchers agree that the lack of appropriate research around the effectiveness of IPE should be addressed through the application of more rigorous evaluative methods to comprehend the potential impact of IPE on professional practice and health outcomes.2,14 Walsh and colleagues recognize it is the methodological difficulties that have limited researchers’ ability to generate this evidence thus far.19

Members of CAIPE issued a report that extensively reviewed IPE evaluations, and suggested the need to use a range of methodologies in the investigation of interventions to strike a balance between evaluation of process and of outcome. Authors of this article also suggested qualitative techniques for the former and quantitative techniques for the latter. A scarcity of data exist to show how long changes in attitude or knowledge are sustained and how learning applies to practice post-IPE.10

We recognized the need both to evaluate the effectiveness of our IPE strategy and to contribute to the growing IPE evidence base. In this article, we describe our IPE initiatives by means of the learning theory that underpins them and categorize the expected learning outcomes using levels 1-3 of the Kirkpatrick/Barr model (Table 1).

METHODS

Interprofessional education is delivered as a strand throughout Durham University’s four-year master of pharmacy (MPharm) curriculum, which is described by Husband and colleagues.20 For the first two years of both the medicine and pharmacy undergraduate programs, students are located on the same campus. Interprofessional education starts within the second week of both programs, at a time when serendipitous and informal interprofessional encounters have taken place between new and returning medical and pharmacy students. Our curriculum developers have followed a strategy, as has been reported elsewhere, 21 that IPE should occur at the earliest opportunities in preregistration education to avoid students developing negative stereotypes and a preference for uniprofessional working over multiprofessional practice. In the United Kingdom, the single route to registration with the professional body for pharmacy is a 4+1 model where four years of undergraduate study are followed by one year of statutory training in employment. Once this is completed, a student may apply to join the pharmaceutical register. This approach is contrary to that advocated by Areskog,22,23 and Pirrie and colleagues24 who believe that IPE should be introduced after students have a clear comprehension of their professional roles.

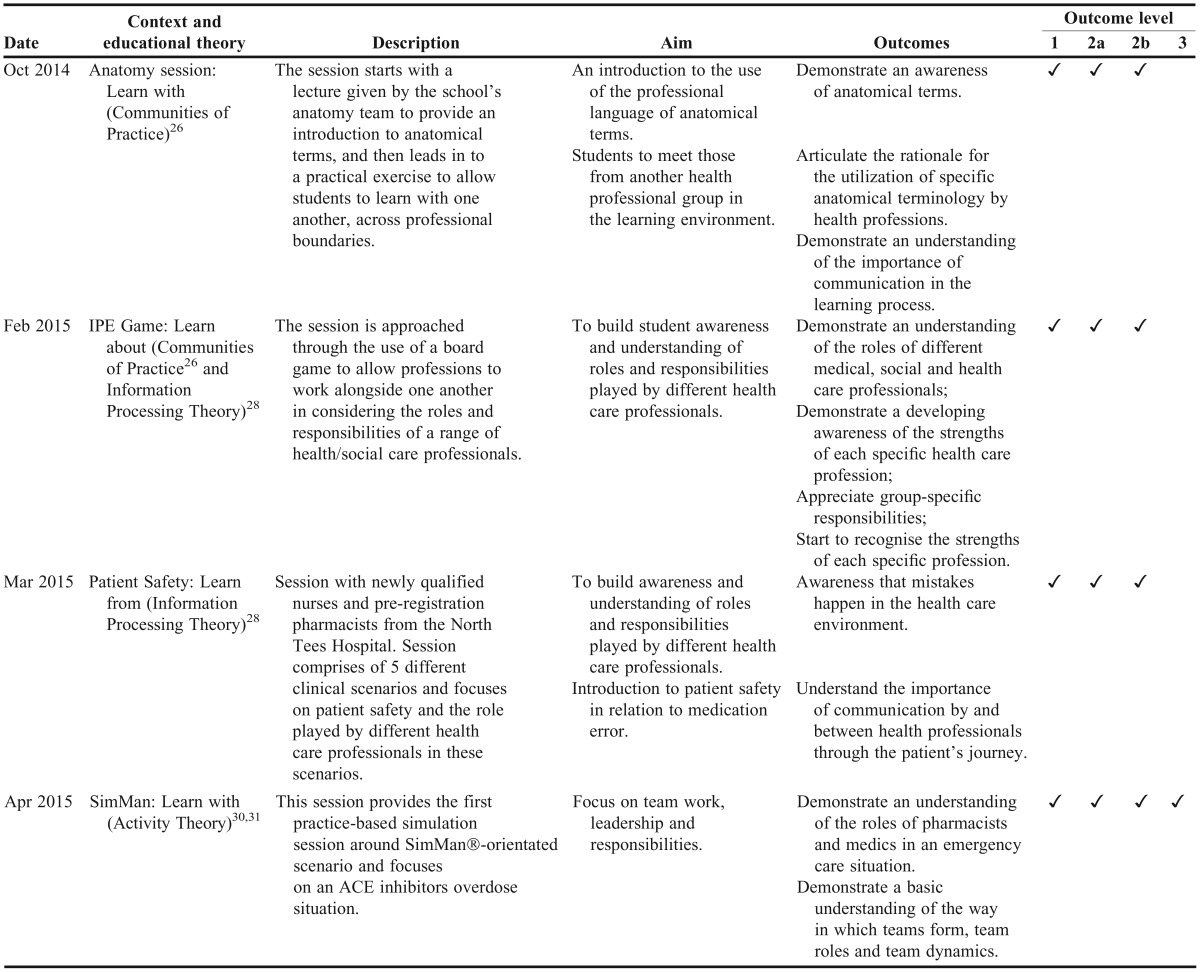

Four to five sessions each academic year existed within the structure, where interprofessional working was revisited with increasing levels of sophistication and complexity as students progressed, as aligned to the concept of the spiral curriculum.20 In designing the IPE sessions, there is no one ideal location for IPE within the curriculum; rather, there are many opportunities for enhancing learning through IPE. Sessions in level 1 (year 1) were mainly biprofessional, with all sessions including students from the undergraduate medicine program, and one session also including nurse practitioner students. In subsequent levels, students from other programs including social care, education (both from the same institution), and nurses (from a neighbouring institution) joined the pharmacy students.

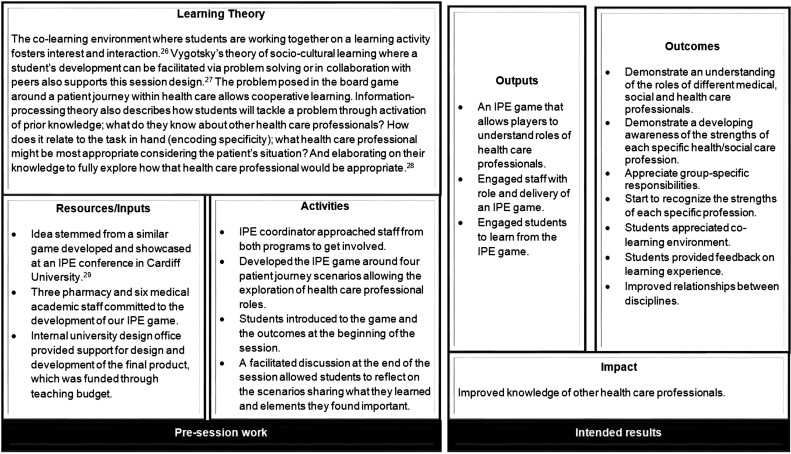

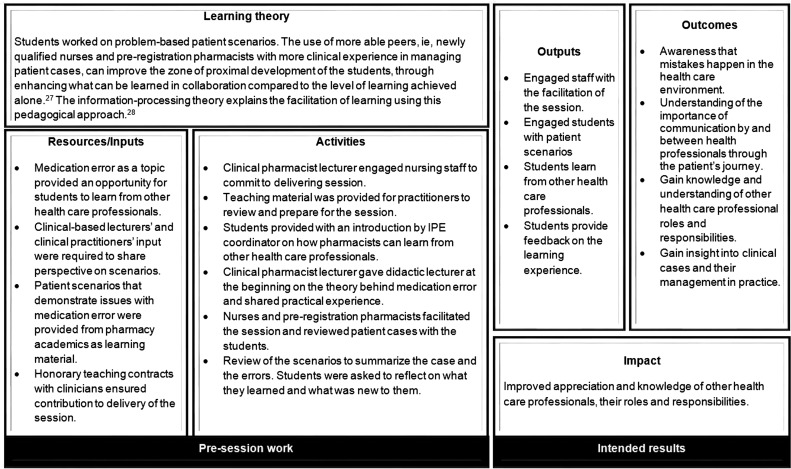

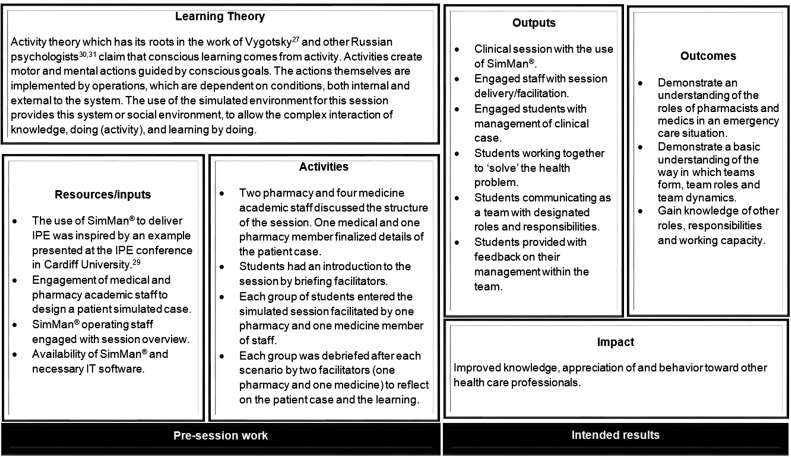

Year 1 of the pharmacy program hosted four IPE sessions, the descriptions of which, and associated aims and expected pedagogical outcomes categorized using the Kirkpatrick/Barr model are summarized in Table 2. Further to this, logic diagrams25 have been constructed to show how each session works and link outcomes with the session activities and processes, and the theoretical assumptions that underpin them (Appendix 1a-d). Logic models have been found to facilitate thinking, planning, and communication about intervention objectives and accomplishments, and have been adopted here for the clear description of each IPE session as an educational intervention.25

Table 2.

Learning Outcomes and Outcome Levels of Interprofessional Education Sessions

We used a mixed methods approach to explore the students’ learning experience and outcomes and the context in which learning occurs. We aimed to evaluate the IPE strategy within level 1 and better comprehend how implementation, causal mechanisms, and contextual factors shape learning and result in the outcomes experienced by students.

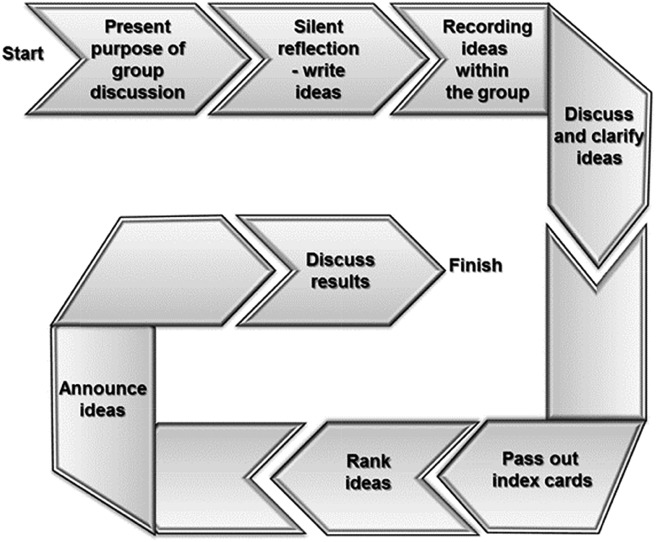

The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) is an evaluative methodology described as “semi quantitative and qualitative”32 in which responses from participants are based on a single topic. The NGT, which was initially developed for marketing research, has been employed in addressing potentially complex qualitative concepts and has become useful in examining education, policy, and research. The methodology requires direct participant involvement (in a small group setting) in a way that is nonhierarchical, and where all participants have an equal voice and all responses to the topic have equal validity.33 The steps with NGT are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An activity flow diagram for a nominal group discussion.

The NGT sessions were held after the second (IPE Game), third (Patient Safety) and fourth (SimMan®) IPE sessions. Students were briefed by the facilitator as to the purpose of the discussion and then asked to reflect in writing on their most recent IPE experience, and in particular to list negative and positive reactions. Rich data obtained through this method allowed aspects of context, implementation of delivery, and causal mechanisms to be explored from the student perspective. There has been debate as to what constitutes the optimal size group for NGT, with suggestions generally ranging from five to nine.33 At each NGT session, up to 10 students were invited to ensure this quotient was met.

Student experience of IPE was measured quantitatively after each IPE session throughout the year using two validated tools for exploring students’ self-assessment of their attitudes to collaborative learning and working. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) 34 and the 12-item adapted version of the 18-item Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS) 35 were used to detect changes in attitudes over time. These tools have been used in various studies for graduate36 and undergraduate students37-39 as well as practicing professionals.40

Despite numerous studies, it is still unclear which scale is superior for finding attitude differences among students in tested health professions. The RIPLS was designed to assess novice students’ attitudes toward interprofessional learning, while the IEPS assesses perceived attitudes about team collaboration within the students’ own profession. The IEPS may thus be appropriate for advanced or senior students once they have had greater exposure to members of their own profession.41 However, due to the lack of empirical evidence to support this, we employed both scales but used the RIPLS at the earliest point, which was in the second week of the students’ program, when they are still considered novices, and the IEPS was added in at the second data collection point, after students had time to integrate with members (classmates, more advanced students, staff) of the same profession.

A further questionnaire was constructed using the accumulated statements from each of the three NGT sessions. Statements were listed and accompanied with a five-point Likert scale to measure level of agreement. Students were asked to rate their response to each statement in relation to each of the four IPE sessions they had participated in.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the School of Medicine, Pharmacy and Health Ethics Sub-Committee within Durham University to survey students through pre- and post-session questionnaires and via partaking in nominal group discussions. All students were provided with participant information leaflets and asked to provide written informed consent to participate in the study.

The cohort studied were the year 1 undergraduate pharmacy students (n=81). RIPLS and IEPS questionnaires were administered to and collected from the whole cohort at the beginning of each of the facilitated sessions. For the NGT, an academic mentor (AP) from the year 2 pharmacy cohort invited students to participate in the studies. This was carried out using a convenience sampling approach. Different students attended at each of the three data collection points. Again, the first NGT session took place after students had experienced both the Anatomy course lecture and the IPE game because the former provided an opportunity for the two cohorts of students, pharmacy and medicine, to learn with one another but did not include any form of interaction. Subsequent NGT sessions took place after the Patient Safety session and the SimMan® session.

All data from questionnaires were put into Microsoft Excel worksheets and were checked for completeness. Not all 81 pharmacy students attended all four of the IPE sessions due to an approved or unapproved absence, and therefore were unable to complete the questions pertaining to that session, so only their completed answers where included in the analysis. Quantitative data from the two questionnaires (RIPLS and IEPS) were analyzed using basic descriptive statistics at baseline and post-intervention across all four IPE sessions, as was the final questionnaire. Responses to the statements over the various data collection time points were tested for significant difference using the chi-square test, where statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Data from students’ positive and negative reflections about their IPE experiences, which they ranked in order of importance, provided a descriptive evaluation of the IPE session. The focused reflection that followed was transcribed verbatim from audio recordings by one author (AP) and checked for accuracy by another (HN). They were then analyzed individually by two authors (HN and ZN) using framework analysis as described by Ritchie and Spencer.42 Resultant themes were discussed between the two authors (HN and ZN) for agreement and clarification, and a third author was consulted to mediate any discrepancies (IO).

RESULTS

The response rates for the RIPLS, IEPS (both of which had 3 data collection points), and final questionnaire were 81.4% ±3.4%) (n=66), 79.1% (±5.7%) (n=64), and 73.2% (n=59) respectively.

Responses for both RIPLS and IEPS were highly positive in all subsections (RIPLS consisting of: teamwork and collaboration; professional identity; and roles and responsibilities. IEPS consisting of: competency and autonomy; perceived need for cooperation; and perception of actual cooperation). Across all statements within both the RIPLS and IEPS, the chi-square analysis showed no statistical difference in students’ responses when compared to students’ baseline responses, or when compared longitudinally with students’ responses throughout the academic year.

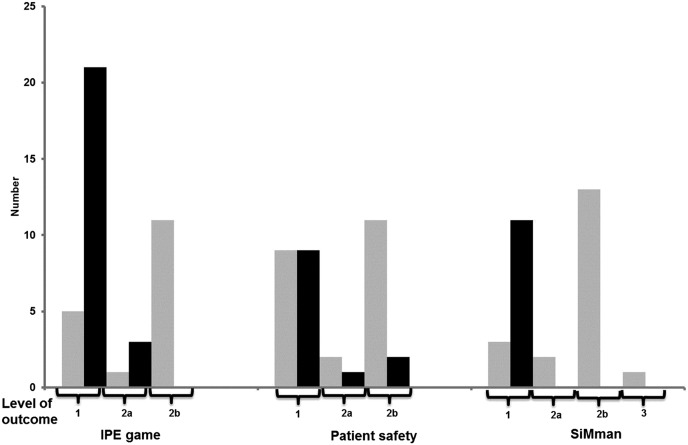

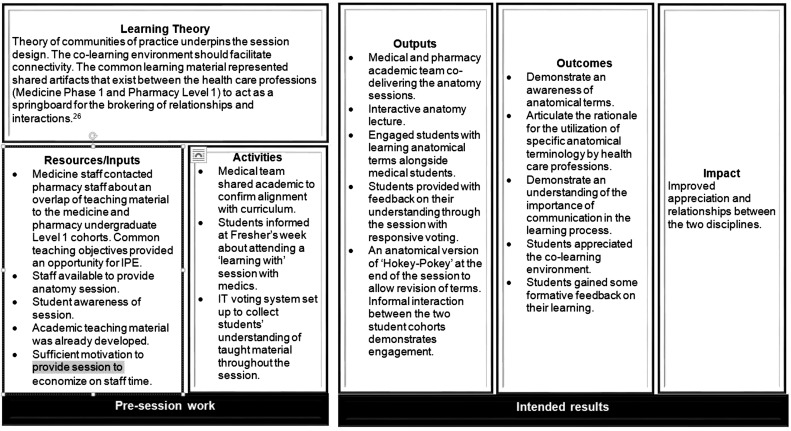

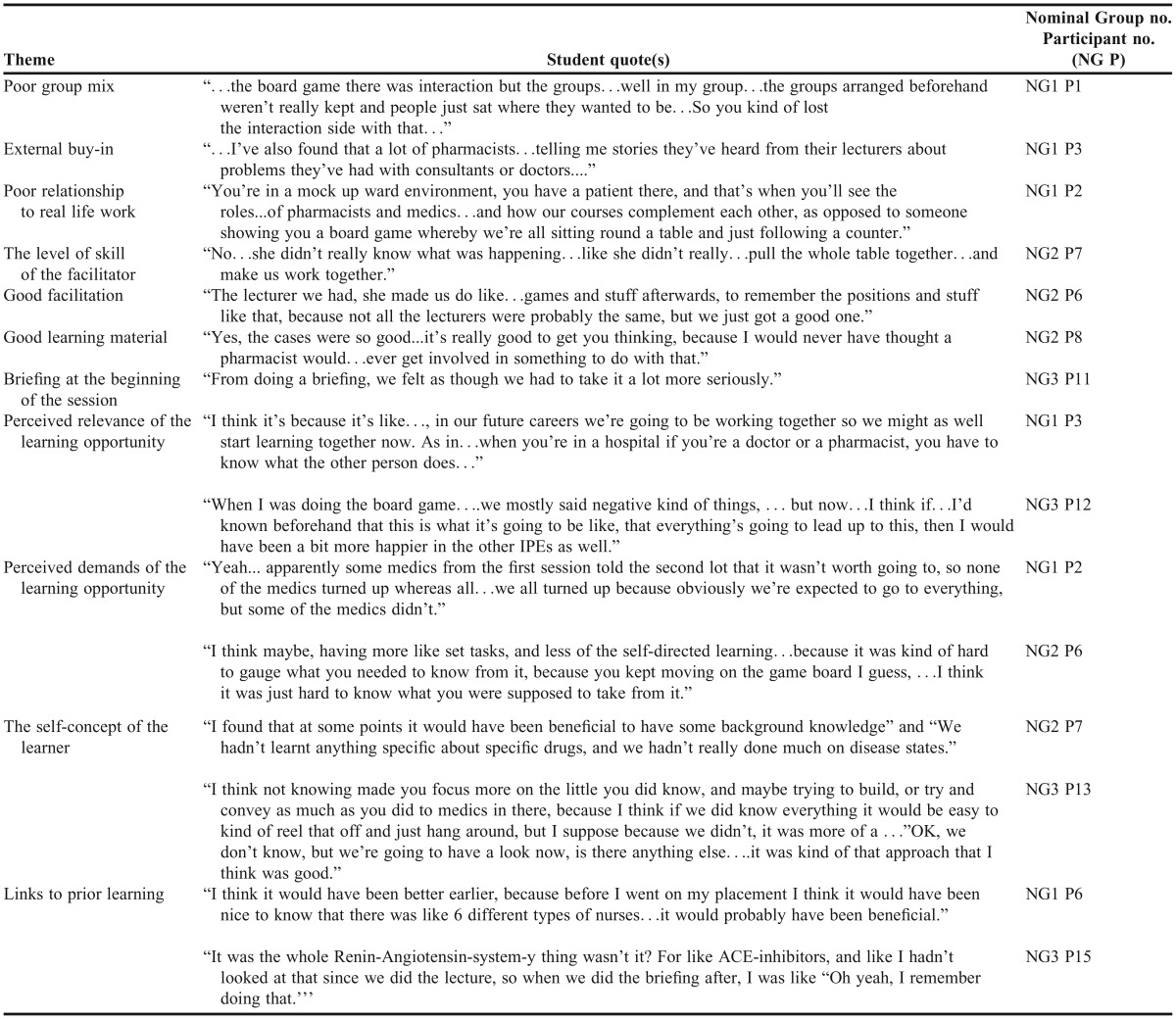

A different set of five students participated in each of the three NGT discussions. These students were those from the original 10 who agreed to participate. All reflections from each NGT session were classified by level of outcome using the Kirkpatrick/Barr model and also by their positive or negative connotation as displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The number of statements of a positive (grey) and negative (black) connotation from each of the NGT sessions that related to the levels of outcomes categorized by Kirkpatrick/Barr (1=Learner’s reaction; 2a=Modification of attitudes/perceptions; 2b=Acquisition of knowledge and skills, and 3=Change in behavior).13,14

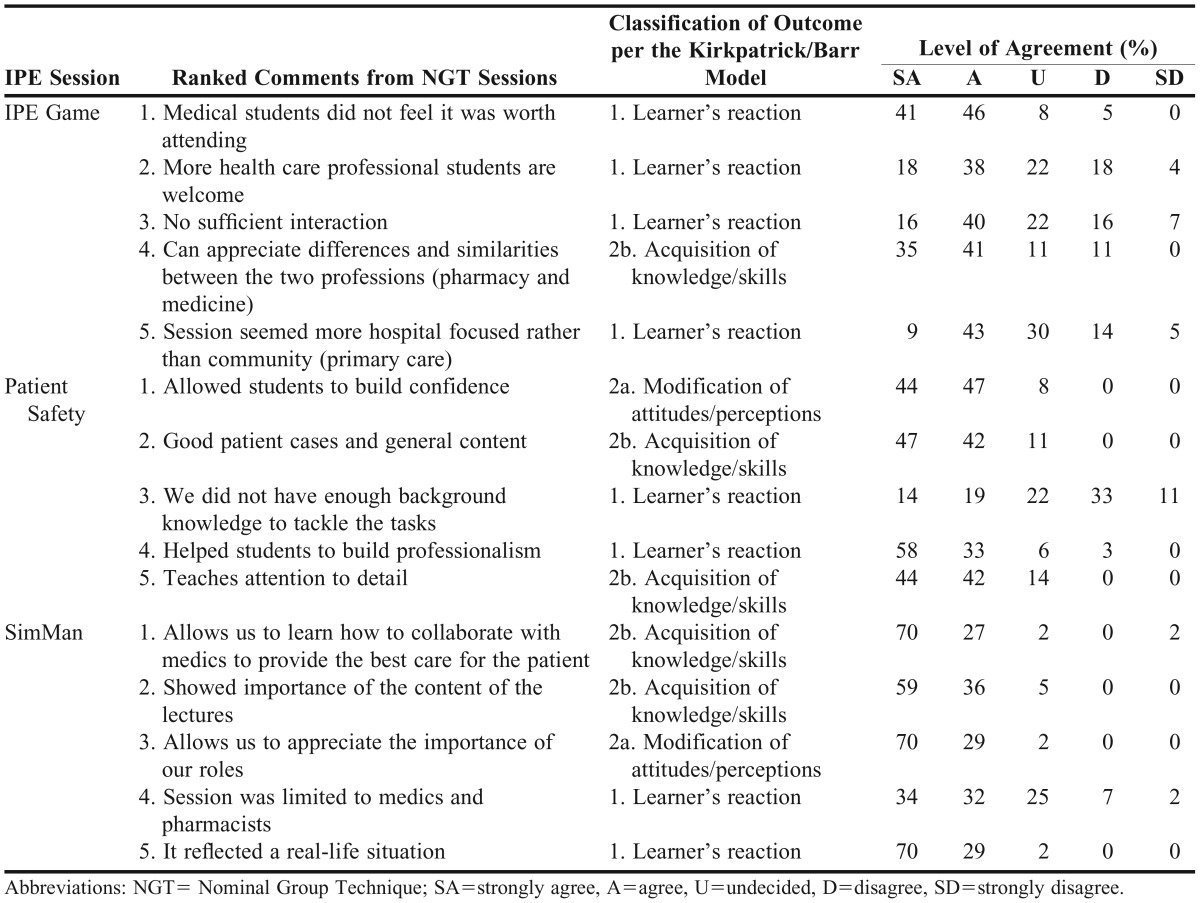

The five most important reflections as ranked by individuals within the NGT sessions have been identified and level of agreement with these statements in relation to the IPE session has been investigated within the entire cohort from the final questionnaire that was administered (Table 3).

Table 3.

Items Ranked Most Important from the Nominal Group Technique Discussions and Interprofessional Student Agreement

The findings from the nominal group discussions following on from the ranking of ideas are presented as themes based on the students’ experiences in each of the IPE sessions. The themes identified inductively through the natural course of the discussion and featured in all three NGT sessions. One theme, which every student from each of the NGST discussions contributed to, related to the organization of the IPE session (which relates most closely to the behaviorist focus upon outcomes, namely Kirkpatrick/Barr model’s level 1 of outcome classification: leaner’s reaction).

Many of the following themes generated from claims of the pharmacy students in the three NGT discussions (NGT1-3 between pharmacy students P1-P15) are commonly reported in the evaluation of IPE delivery and are recognized as crucial factors for its success (Appendix 2):

- Not achieving an appropriate group mix to allow a heterogeneous learning environment;43

- External buy-in44,45 which is also one of the prerequisites stated in the contact hypothesis to frame an environment conducive for interprofessional working;11

- Poor relationship to real life work;44,45

- The level of skill of the facilitator.44,46

Some students made some positive comments on good facilitation, learning material and briefings provided at the beginning of the sessions which enhanced their learning experience.

Four further principles were identified that relate to adult and experiential learning:

1. Perceived relevance of the learning opportunity. Eleven of the 15 students across the three NGT groups made comments that began to demonstrate reflection in how the information was relevant to their educational and professional progress:

The perceived relevance of an educational experience or opportunity is a powerful facilitator to engagement and learning.47,48 Students related better to the sessions where they could envisage the applicability to their future role and profession.49

2. Perceived demands of the learning opportunity. A majority of the students (10 of the 15 students across NGT1-3) also displayed how their perceptions of their learning environment and what was expected from them affected their learning experience. The first NGT discussion revealed that some negativity from students from other groups toward the board game affected student motivation to attend and also engage:

This demonstrates that the explicit message of attendance was clear to pharmacy students; however this was counteracted by the implicit messages from the disengagement and negativity of other students. Some of the students claimed that knowing the aims, objectives and learning outcomes of the sessions could have made them more ready to engage and enrich their learning experience.

3. The self-concept of the learner. Students (nine of the 15 across NGT1-3) reflected on the level of challenge that each IPE session posed and related that to aspects of their self-concept. Students wish to view themselves as competent, self-directed, appropriately self-evaluative and exercising choice;48,50 any phenomenon that attacks this may produce resistance and rejection.

There was some feeling that where the level of challenge was perceived too high, the enjoyment of the session was detrimentally affected.

The learning gap between what students think they know and what they think they need to know can stimulate learning through revealing learning needs and motivating learners to close the gap. However, if that gap is too large the student’s self-concept can be negatively affected and demotivation and dejection can result, which counteracts productive and engaged learning.51,52

Conversely, some students found where this disjuncture existed, particularly in the SimMan® session, they gained an appreciation of the extent and depth of knowledge they would one day be expected to possess. They valued this stark realization in knowledge differential toward gaining a better understanding of the pharmacist’s role and also in recognizing the journey of development they were travelling to achieve.

4. Links to prior learning. Lastly, most students (eight out of the 15 across NGT1-3) identified and appreciated where IPE sessions related to earlier experiences or learning within the curriculum. The foundations provided by the previous iteration should serve to support new learning, but also improve learners’ approach to IPE where they feel more comfortable.48,53

DISCUSSION

The baseline data of this year 1 cohort of health professions students demonstrated a high level of preparedness and positivity toward IPE. This self-reported attitude and perception as assessed by the RIPLS and IEPS did not change significantly from the IPE sessions throughout the academic year. Researchers have acknowledged the self-reported nature of these two tools, which necessitates caution in interpreting their results as they may not be representative of actual interprofessional learning attitudes within a health care setting.54,55 Further studies have suggested that there may need to be a significant differential between levels of exposure to IPE for these tools to be sensitive enough to detect a change in perception and attitudes.41,56 Lie and colleagues conclude that no single scale may adequately record attitude change, and multiple strategies including qualitative measures should be incorporated to best study attitudinal change. Nevertheless, the reported positive attitudes toward IPE here can be considered as the optimum foundation for student engagement and motivation for learning within the experience.41

The NGT discussions showed a shift from mixed responses to more positive comments through the progressive IPE sessions. Also, there were initial responses within the first session (NGT1) that related mostly to the organization of the IPE sessions and the learner’s reaction, as they saw the session facilitator and the classroom setting as being very influential in their learning experience. After subsequent IPE sessions, responses became more abstract as students made reference to the development of their knowledge and skill, higher levels of outcome on the Kirkpatrick/Barr model, rather than the tangible external elements. This internalization of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors characteristic of the profession develop through a process of socialization and gaining experience in the practice setting. Students learn to become a member and practice using the aforementioned characteristics by participating in communities of practice.57 Interprofessional education sessions and clinical placements, and interaction with others in their own and related professions, offer opportunities for such learning. The pattern of more developed outcomes was also reflected in the ranked comments about the IPE sessions, where levels of outcomes reported became more sophisticated in nature relating more to the impact on attitudes, knowledge, skills and behaviors. The final questionnaire allowed the generalizability of these comments to be tested within the entire cohort (Table 3). The levels of agreement or strong agreement were generally high (>50%) across all the statements except for the statement pertaining to the patient safety session: “We did not have enough background knowledge to tackle the tasks.” Only 35% of the cohort agreed with this statement, 22% were undecided, and 44% disagreed. This finding likely reflects the differences in academic ability/self-efficacy among the students rather than the level of challenge of the tasks.

Students enter the pharmacy degree program, for the most part, from a college or equivalent where teaching is traditionally didactic and directed by the educator. Higher education requires a shift toward more self-directed and learner-motivated learning styles, which can be quite a difficult transition for some students to navigate and adjust to. The structure of the IPE sessions was designed to accommodate this transition and thus commenced with an interactive lecture (the anatomy session). This involved transfer of knowledge from educator to student where students could then only be expected to be able to recall knowledge (“knows”), the lowest form of competence based on Miller’s triangle.58 Subsequent sessions were based around small-group work where students became more self-directed, initially with an exploratory IPE game, then a facilitated patient case scenario, both of which required students to use individual or collaborative knowledge (“knows how”) in solving the issue at hand. The final session of simulated practice was pitched at the next stage of the triangle, and students were expected to “show how” to apply their knowledge and skill.

The three nominal group discussions yielded four themes in particular which related to principles of adult learning theory. These reflect how the students related to the learning opportunities presented to them in the IPE sessions. Arriving at these themes demonstrates how the NGT procedure has given the opportunity for students to reflect collectively among peers and also documents how students demonstrate the three dimensions of reflection described by Jay and colleagues.59 They initially describe the matter for reflection – an attitude, behavior, or action within or as a consequence of the IPE session (descriptive dimension), the group discussion allows comparison of alternate views and perspectives of that same matter (comparative dimension), and establishment of a renewed perspective (critical dimension).59 The data collection process has provided “a place, a space, and a time for reflection” as recommended by Clark, that is essential for transformative learning where students can think about their perspectives as well as those of others.60

CONCLUSION

The RIPLS and IEPS were ineffective in providing any information on development of students’ readiness and motivation toward interprofessional working. However, we found that the NGT is an effective way to capture student experience and record growth in learning and behaviors. The nominal group discussions and prioritized statements provided students an opportunity to reflect on their experience. Students explored meaning and began to understand how their experiences influenced their plans and motivation for future learning and development. Sharing the process with peers seemed to facilitate the reflective capability of the students as ideas and perceptions were bounced off one another, refined, and reconsidered. This outcome would support the global use of reflective portfolios by students undertaking an IPE program, but with an added dimension of peer review and potentially assessment. In this way students would have individual longitudinal records of their journey, as they navigate their own expectations and emotions and the reactions to others, and appreciate these in the context of subsequent behaviors and dynamics. The peer-review component would allow students to revisit their experiences, compare and critique with others, and potentially renew and progress their understanding toward achieving transformative learning. If each student were able to engage with this process effectively, it could be an invaluable way to demonstrate students’ growth in professional identity, attitudes, and behaviors toward preparation for collaborative practice.

Appendix 1a. Logic Model for the Anatomy Session

Appendix 1b. Logic Model for the IPE Game Session

Appendix 1c. Logic Model for the Patient Safety Session

Appendix 1d. Logic Model for the SimMan® Session

Appendix 2. Student Quotes from Specific Nominal Group Discussions that Relate to the Generated Themes

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindeke LL, Block DE. Interdisciplinary collaboration in the 21st century. Minn Med. 2001;84(6):42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S. What’s so great about collaboration? We need more evidence and less rhetoric. BMJ. 2000;320(7241):1022–1023. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7241.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindeke LL, Sieckert AM. Nurse-physician workplace collaboration. Online J Issus Nurs. 2005;10(1):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazirani S, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, Cowan M. Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on communication and collaboration among physicians and nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(1):71–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggs JG, Norton SA, Schmitt MH, Sellers CR. The dying patient in the ICU: role of the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(3):525–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.03.008. xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buring SM, Bhushan A, Broeseker A, et al. Interprofessional education: definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):Article 59. doi: 10.5688/aj730459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finch J. Interprofessional education and teamworking: a view from the education providers. Br Med J. 2000;321(7269):1138–1140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7269.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS Executive South West. Achieving health and social care improvements through interprofessional education. Report of the 7th meeting. 2000.

- 9.CAIPE. Interprofessional education – a definition. CAIPE Bulletin. 1997. Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education, London.

- 10. Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. Evaluations of interprofessional education: a United Kingdom review for health and social care: The United Kingdom Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education and The British Educational Research Association. 2000. London.

- 11.Hewstone ME, Brown RE. Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hean S, Craddock D, O’Halloran C. Learning theories and interprofessional education: a user’s guide. Learning in Health Soc Care. 2009;8(4):250–262. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluation of Training. In: Craig RL, Bitten LR, editors. Training and Development Handbook. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1967. pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. Evaluating interprofessional education: two systematic reviews for health and social care. Br Educ Res J. 1999;25(4):533–544. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNair R, Brown R, Stone N, Sims J. Rural interprofessional education: promoting teamwork in primary health care education and practice. Aust J Rural Health. 2001;9(Suppl 1):S19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter J, Barnes D, Dickinson C, Wooff D. Outcomes of interprofessional education for community mental health services in England: the longitudinal evaluation of a postgraduate programme. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(2):145–161. doi: 10.1080/13561820600655653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollard KC, Miers ME, Gilchrist M, Sayers A. A comparison of interprofessional perceptions and working relationships among health and social care students: the results of a 3-year intervention. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(6):541–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphris D, Hean S. Educating the future workforce: building the evidence about interprofessional learning. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(Suppl 1):24–27. doi: 10.1258/135581904322724103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh CL, Gordon MF, Marshall M, Wilson F, Hunt T. Interprofessional capability: a developing framework for interprofessional education. Nurse Educ Pract. 2005;5(4):230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husband AK, Todd A, Fulton J. Integrating science and practice in pharmacy curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014 2014;78(3):Article 63. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horder J. Interprofessional education for primary health and community care: present state and future needs. In: Soothill K, MacKay L, Webb C, editors. Interprofessional Relations in Health Care. London, UK: Arnold; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Areskog NH. The need for multiprofessional health education in undergraduate studies. Med Educ. 1988;22(4):251–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Areskog NH. Multiprofessional education at the undergraduate level – the Linkoping model. J Interprof Care. 1994;8(3):279–282. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirrie A, Wilson V, Elsegood J, et al. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Council for Research in Education; 1998. Evaluating multidisciplinary education in health care. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WK Kellogg Foundation. Logic model development guide. Battle Creek; 2004. https://ag.purdue.edu/extension/pdehs/Documents/Pub3669.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2015.

- 26.Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization. 2000;7(2):225–246. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vygotsky LS. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt HG. Problem-based learning: rationale and description. Med Educ. 1983;17(1):11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1983.tb01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Learning and working together to improve safety through better prescribing. Cardiff University; Wales: 2013. Paper presented at: Interprofessional Education Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bedny GZ, Seglin MH, Meister D. Activity theory: history, research and application. Theor Issues Ergon Sci. 2000;1(2):168–206. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engeström Y, Miettinen R, Punamäki RL. Perspectives on Activity Theory. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry J, Linsley S. The use of the nominal group technique as an evaluative tool in the teaching and summative assessment of the inter-personal skills of student mental health nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 2006;26(4):346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potter M, Gordon S, Hamer P. The nominal group technique: a useful consensus methodology in physiotherapy research. N Z J Physiother. 2004;32:126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS) Med Educ. 1999;33(2):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFadyen AK, Maclaren WM, Webster VS. The Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS): an alternative remodelled sub-scale structure and its reliability. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(4):433–443. doi: 10.1080/13561820701352531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruebling I, Pole D, Breitbach AP, et al. A comparison of student attitudes and perceptions before and after an introductory interprofessional education experience. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(1):23–27. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.829421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keshtkaran Z, Sharif F, Rambod M. Students’ readiness for and perception of inter-professional learning: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(6):991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFadyen A, Webster V, Strachan K, Figgins E, Brown H, McKechnie J. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale: a possible more stable sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(6):595–603. doi: 10.1080/13561820500430157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McFadyen A, Maclaren W, Webster V. The Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS): an alternative remodelled sub-scale structure and its reliability. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(4):433–443. doi: 10.1080/13561820701352531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid R, Bruce D, Allstaff K, McLernon D. Validating the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) in the postgraduate context: are health care professionals ready for IPL? Med Educ. 2006;40(5):415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lie DA, Fung CC, Trial J, Lohenry K. A comparison of two scales for assessing health professional students’ attitude toward interprofessional learning. Med Educ Online. 2013;18:21885. doi: 10.3402/meo.v18i0.21885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Huberman AM, Miles MB, editors. The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. pp. 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsell G, Spalding R, Bligh J. Shared goals, shared learning: evaluation of a multiprofessional course for undergraduate students. Med Educ. 1998;32(3):304–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsell G, Bligh J. Interprofessional learning. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74(868):89–95. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.74.868.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson ES, Lennox A. The Leicester model of interprofessional education: developing, delivering and learning from student voices for 10 years. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(6):557–573. doi: 10.3109/13561820903051451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelley A, Aston L. An evaluation of using champions to enhance inter-professional learning in the practice setting. Nurse Educ Pract. 2011;11(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schön DA. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knowles MS, Holton EF, III, Swanson RA. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engeström Y. Expansive visibilization of work: an activity-theoretical perspective. Comput Supported Cooperative Work. 1999;8(1-2):63–93. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogers CR. Freedom to Learn. Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jarvis P. Adult Learning in the Social Context. Vol. 78. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vermunt JD, Verloop N. Congruence and friction between learning and teaching. Learn Instr. 1999;9(3):257–280. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolb AY, Kolb DA. Learning styles and learning spaces: enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Acad Manage Learn Educ. 2005;4(2):193–212. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams B, Boyle M, Brightwell R, et al. A cross-sectional study of paramedics' readiness for interprofessional learning and cooperation: results from five universities. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(11):1369–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thannhauser J, Russell-Mayhew S, Scott C. Measures of interprofessional education and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(4):336–349. doi: 10.3109/13561820903442903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J, Flynn K. Student satisfaction and perceptions of small group process in case-based interprofessional learning. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):431–433. doi: 10.1080/01421590802047323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63–S67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jay JK, Johnson KL. Capturing complexity: a typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching Teacher Educ. 2002;18(1):73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark PG. Reflecting on reflection in interprofessional education: implications for theory and practice. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(3):213–223. doi: 10.1080/13561820902877195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]